Abstract

Background

There is an urgent need to ensure that food production is maintained in response to either a reduction in use or lack of availability of natural resources. To this end, several strategies have been investigated to determine which agronomic approaches may improve crop yields under conditions of reduced water and/or nutrients provision, with special attention upon nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P). New technologies and practices have been developed for key commercial crops, such as tomatoes. However, few of these are widely adopted in the field and evidence of their value in this production setting is limited.

Methods

This protocol sets out a systematic map methodology that aims to provide a coherent synthesis of the available evidence among the literature on the techniques and management approaches that may ensure the productivity of field-grown tomatoes under conditions of water-, N- and/or P-deficits, either as single or combined stresses. To conduct the literature search, a search strategy was produced to define the scope of the systematic map and to allow reproducibility of the approach. A list of published and unpublished sources of literature were selected and a preliminary trial identified best-fit-for-purpose search-terms and -strings. A literature screening process was set with consistency checks amongst reviewers at the title, abstract and full text screening stages. A series of eligibility criteria were defined to ensure objectivity and consistency in the selection of studies that are best suited to address the research question of the systematic map. In addition, a coding strategy was designed to set the means for meta-data extraction out from the literature for review. A drafted structured questionnaire will serve as the base for collating the meta-data to produce a database where variables will be queried for the evidence synthesis. This work is expected to inform stakeholders, researchers and policy makers regarding the extent and nature of the existing evidence base, and so serve as a basis by-which specific approaches may be highlighted as potential focal-areas in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Among the global challenges facing society in the twenty-first century are the consequences of intensive agriculture as a major contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and consequent global warming and climate change. Identifying measures that help agriculture adapt to, and mitigate against, such negative contributions is essential. The farming sector is being asked to adopt new measures to help address such challenges at a time when food demand is increasing due to population growth, which is expected to peak at ca 9.8 billion by 2050 [1, 2]. Among the drivers of agriculture’s contribution to climate change is excessive synthetic nitrogen (N) fertiliser use. In 2015, agriculture was responsible for 94% of the total NH3 emissions in the EU [3, 4]. At the same time, the intensive exploitation of natural resources by agriculture has led to the exhaustion of phosphorus (P) fertiliser sources. This scenario presents the need for a global transition towards more sustainable holistic and restorative agricultural approaches [4, 5].

Water and nutrients are lost in many ways before they are acquired by crop plants. It is estimated that large quantities of water (from rain or irrigation systems), is lost in the field by percolation, run-off and evaporation and such losses are increased by intensive ploughing practices. Once acquired by the crop, water it is used for plant metabolic functioning as well as growth and yield. On average, 90% of the water required by crop-plants is lost through transpiration [6]. In addition, global temperature rise due to global warming is expected to increase the evapotranspiration rates of plants, which will be translated into a loss of water for biomass accumulation and yield. Water is already a scarce resource in many parts of the world, and it is commonly applied to crops by regular irrigation in dry and even temperate regions [7, 8]. As an impact of climate change, weather stochasticity and the increased occurrence and extended periods of drought are also anticipated to increase water demand for food production and conflict with other society needs [9]. Hence, the water shortage expected in the coming years, combined with a subsequent increase in demand, will make this resource increasingly expensive [9]. Similarly, on average, only 30–50% of applied synthetic N fertiliser is consumed by the crop and the rest is mainly lost in ground-water, causing contamination to groundwater bodies and surface water systems, or volatilised to the air [10, 11]. Historically, conventional farming would apply an excess of nutrients to crops to avoid nutrient deficiency and ensure yields regardless of any negative environmental impacts. More recently, regulations and policies have forced farmers to reduce the quantity of (synthetic) N fertiliser applied to the crops, with N and P inputs receiving special attention as most important soil contaminants and agents of eutrophication [12]. To comply with these regulations, farmers have had to lower and adjust the timing and formulation of such inputs to ensure that levels-applied better-match crops actual nutrient needs. In controlled environment systems, soilless cultures have allowed the re-utilisation of water and nutrients by closing the water- and nutrient-cycles, resulting in a reduction in the amounts wasted [13, 14]. In open field production, the quantity of fertiliser applied depends on the irrigation system and prevailing pedo-climate [13]. Soil testing, drip irrigation and monitoring and nutrient delivery guidelines, such as petiole sap testing guidelines and tissue analysis, have also helped reduce inputs by determining crop requirements and knowing when those are needed [13]. Despite these efforts, there is still an elevated percentage of water and nutrients being lost. In general, the potential loss of irrigation water and fertilisers is greater in open field production than in protected cultivation as these systems allow for a better control of environmental factors and are often equipped with means to isolate the crop from the soil. Also, in advanced systems engineered-devices may collect what is not used by the plants [15]. In a system comparison study carried out in Spain, the irrigation water per ton of tomatoes almost doubled in the open field system compared to that from protected cultivation [14]. However, protected cultivation also needs to ensure use-efficiency of farming inputs and is unlikely to offer a single solution to overcome water and nutrient deficit stress of field production. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify alternative strategies to secure sustainable food production through resilient systems that can maintain yields under conditions of low usage and/or multiple deficit-stresses.

Tomato is considered one of the top most important fruit and vegetable crops worldwide, this being because of the large area occupied for its cultivation as for its economic value [13, 16]. In addition, tomato represents a genetic model species for the study of crop production, and presents many diverse types for exploitation; consequently, it has generated interest for identifying strategies capable of maintaining yields under combined deficit stresses [17, 18]. Table 1 lists several of the approaches that have been under study towards this aim on field tomato. In open field production, some strategies improving water and nutrient use-efficiency have been frequently adopted, e.g. drip irrigation, and mulching [13, 17]. Others, however, remain under studied and have rarely been put into practice on commercial farming due to either the difficulty in implementation or for economic reasons [19,20,21,22]. Technologies and biological strategies such as grafting, the use of biostimulants such arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) or plant growth promoting rhizosphere microorganisms (PGPR) have often been studied by researchers and under controlled environments but there are fewer known successful applications to open field conditions which may have conditioned the adoption at a commercial scale [22,23,24].

Genetic improvement of commercial crop varieties has also offered promising results. However, the development of cultivars resistant to resource-stress, such as water, have often focused on crop survival rather than maintaining or improving crop productivity, which are not necessarily compatible [25, 26]. Similarly, many genetic studies are carried out in research laboratories, but their use on commercial in-field production are difficult to find. To date, efforts to assemble and collate the large body of empirical evidence describing approaches that enhance tomato production in the field with reduced use of fertiliser N or P and water are lacking. Such research would be of interest to tomato growers, since most of the area that is being used globally and by leading tomato producing countries is still under field cropping systems (Table 2). Evidence maps can offer a methodological approach to address this and help understand which approaches are used and/or being tested, as-well-as which approaches have been neglected. Such evidence synthesis can also help identifying knowledge gaps, and so where more evidence is required, and the location of such key-data for further studies.

To date, and to the authors’ knowledge, there is one evidence-synthesis that may share some aspects of the evidence map introduced here. The systematic review on climate-smart agriculture was conducted in 2016–2019 by the Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Compendium and funded by the CGIAR Research Programme on the Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security and FAO [33]. This study aimed to identify practices capable of producing food more sustainably and so enhance the resilience (or adaptative capacity) of farming systems and help mitigate the impacts of climate-change. Whilst the systematic map targeted here, shares a common aim with this study, it poses a very different research question to address more-specific foci. The main differences lie in the fact that our study considers: (1) only farm management practices which relate singularly to agronomy rather than including all levels of farm management related to food production (e.g. agroforestry, livestock, postharvest management and energy systems); (2) biological, genetic and technological capacities; (3) a global wide evidence base not limited to a specific geographic or sociological region e.g. developing countries; and (4) only tomato crops as a model subject with respect to productivity (i.e. yield) under conditions of water- and/or N- and P-deficit as abiotic stressors.

The topic addressed by our proposed systematic map is already the scrutiny of significant interest among the scientific international community as well as commercial entities and non-governmental organisations. For example, through recently completed projects such as ROOTOPOWER (EU FP7, 2012–2015), and existing projects such as TRADITOM, TomGEM and TomRes (EU Horizon (H) 2020s projects running from 2015–2018, 2016–2020 and 2017–2020 respectively). All these projects use different approaches and use tomato as the model subject to empower key crops to abiotic stressors resulting from climate change. The systematic map will also collate relevant evidence which has emerged from these projects as part of the synthesis study.

Objectives of the systematic map

The aim of this systematic map is to provide an overview and thorough description of the evidence available on the techniques and management approaches that influence the productivity and resource use-efficiency of in-field tomato cultivation under water, N and P deficit (Table 3). The former (water) due to resource scarcity, and the latter due to the necessity for restricted use (N) and availability declines (P).

The primary research question of this systematic map is:

What evidence exists on the effectiveness of the techniques and management approaches used to improve the productivity of field grown tomatoes under conditions of water-, nitrogen- and/or phosphorus-deficit?

To frame the research question, a preliminary assessment of existing key literature and data on the topic of interest was made. This helped to identify questions that would be adequate to address in an evidence synthesis, and that would generate interest amongst users and research specialists. The appropriateness of the synthesis that was developed by this assessment was then put to evaluation through a specialist workshop held in Mallorca (Spain) in October 2018 with EU-TomRes project partners and stakeholders (see Additional file 1). Discussion and feedback from this workshop helped refine the aims and scope of the systematic map and to further-define the research question.

The research question has been further deconstructed using the ‘Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome’ (PICO) components (Table 3).

A synthesis of the evidence found for both protected and open field cultivation was disregarded as strategies adopted or tested in protected environment conditions (e.g. greenhouses, tunnels, in vitro etc.) differ considerably from field based approaches and often occur in (semi-) controlled conditions where water and nutrients applications are strictly controlled, often using raised-bed and/or hydroponic based where nutrients and water are recycled. Thus, including protected cropping would have increased the body of evidence to such an extent in volume and complexity that the evidence synthesis would no longer be practicable. Similarly, the inclusion of evidence regarding both improvement of tomato fruit quality and yield would generate also a very complex body of evidence. Studies and strategies aiming to enhance tomato quality differ greatly between them depending on the quality or nutritional trait focus of study. Also, in such studies, yield is often inversely affected, disregarded or studied as a secondary outcome. Among the recommendations given by participants in the specialist workshop was the necessity to ensure a simple focal outcome for the evidence synthesis, and that yield, and not fruit quality, would be the best single trait on which to concentrate to ensure a meaningful functional outcome on the impacts of management interventions of water-, N- and P-deficiencies on tomato production. In addition, this evidence will be collated for each resource/stressor individually and in combination and it will cover both positive and negative effects of the interventions regardless of the geographical location of the trials-to help ensure global coverage.

From the findings, the systematic map should also identify knowledge gaps and gluts which may inform future intervention foci for researchers, growers or policy makers.

Methods

Searching for articles

The search strategy has been developed, in an iterative way, to maximise the coverage of the search, and so ensure evidence captured that is sufficient, comprehensive and relevant to meet the guidelines [34] that assures objective addressing of the research question. The search strategy was established by: (1) determining the most appropriate search terms to use for on-line literature searches; (2) choosing key sources of literature for both published and unpublished studies; and (3) defining the criteria to follow through the reviewing process and which would ensure unbiased screening for the inclusion or exclusion of the literature for the systematic map.

The search strategy described here has been constructed to allow future reproduction of the approach. Accordingly, any variations to the protocol should not be encountered, though if they are, shall be restricted to minor and amendments to the protocol will be clearly listed in the final Systematic Map report.

Testing the scope of the search

A scoping study was conducted to find the best-fit-for-purpose search strings to retrieve most relevant literature from the searches. For this, a preliminary list of terms was selected from the familiarisation with relevant literature and through text analysis with the use of CREBP Systematic Review Accelerator online tool [35]. The series of terms identified as potentially relevant where evaluated by experts via specialist workshop (mentioned above), and email correspondence. Further terms suggested by stakeholders and experts were considered in the final list. Each of these terms were further tested against a ‘test-list’ library comprising a set of 47 published articles and other literature known to be relevant to our research question (see Additional file 2).

Search terms

Out from the scoping study a selection of terms was used to build the following search strings, which, in combination form the bases of the search strings used to conduct the literature searches:

- Population::

-

(tomato* OR lycoper*)

- Intervention::

-

(field* OR ground* OR land* OR soil$) AND (water OR drought$ OR nitr* OR “N” OR phosph* OR “P” OR nutrient$ OR “abiotic” OR “climate chang*”) AND (use$ OR uptake$ OR effici* OR optim* OR stress* OR defici* OR resistan* OR toleran* OR “arid” OR adapt* OR availab* OR “content” OR “amount”)

- Outcome::

-

(yield* OR “production” OR productiv* OR weight$ OR “kg” OR “t” OR “biomass”)

The search will use title, abstract and keyword levels and will be restricted to those articles available in the English language. When specification of these text sections is unavailable for any of the literature databases or grey literature sources, searches will be done at the full text level.

No time or document type restriction will be applied.

Terms were built in strings to ensure use of the highest number of term combinations which are most frequently and commonly employed. Terms in the ‘Intervention’ element were separated into three components which, in combination, allowed studies on technical or management interventions for improved water and nutrient use-efficiency in the field to be found. Including terms related to field production may exclude relevant literature not specifying the study design or study conditions at the title, abstract and keyword level. Furthermore, restricting the search with limiting Booleans operators such as ‘NOT’ in combination with terms related to protected cultivation (such as ‘greenhouse’, ‘glasshouse’, ‘controlled environment’…) was considered inadequate since some literature may address both cultivation systems. In such occasions, a number of relevant articles would be excluded by the search if this restrictive Boolean operator was used. Overall, the addition of terms related to in-field studies allowed the largest amount of relevant literature to be returned without returning an unmanageable large volume of irrelevant literature.

Searches for secondary studies such as reviews, meta-analysis and other secondary studies (see Additional file 5) will be conducted separately from primary studies as different search strings and selection of terms are necessary. Reviews and other type of secondary studies usually provide details on the study design or study conditions used to make the observations; but often these specifications are not mentioned at the title, abstract or keywords levels. Therefore, searches for secondary studies will not include terms related to open field observations (field* OR ground* OR land* OR soil$) as part of the ‘Intervention’ element and will not include terms referring to the ‘Outcome’ (yield* OR “production” OR productiv* OR “weight” OR “kg” OR “t” OR “biomass”).

For each publication databases, search terms, ‘wildcards’ and Boolean operators had to be further customised from the search string base described above depending on the capacity to integrate long and complex search strings during the searching queries.

The scoping exercises carried out to test the search strings and terms and help define the search strategy were conducted using the CAB Abstracts and Web of Science Core Collection databases. The combination and performances outcomes of these preliminary scoping searches and the finalized search strings for each publication databases are reported in Additional file 3.

Publication databases

The following bibliographical databases were identified as the main sources for published literature on agricultural studies and those most relevant to the research question:

-

CAB Abstracts (via Web of Sciences)

-

Web of Science Core Collection

-

Zetoc

-

PubAg (USDA—National Agricultural Library)

-

AGRIS (Agricultural Science and Technology Information Systems)

To reduce the amount of non-relevant literature retrieved from each bibliographic database, search results obtained will be refined by the selection of the subject categories identified most relevant from each publication database. The subject categories specific for CAB Abstracts (CABICODES) and Web of Science Core Collection (WoS) were assessed by their utility to withdraw relevant literature from the search hits. The subject categories available from two of the other bibliographic databases (Zetoc and AGIRS) were selected by comparing common fields with CABICODES and WoS subject categories (Additional file 4).

Search engines

Searches will also be carried out through the internet search engines Google (https://www.google.com) and Google scholar (https://www.scholar.google.com). The first 100 results from each search engine, organised by relevance, will be selected, and will be included and examined through the screening process if not identified by other means.

Grey literature and specialist searches

Grey literature such as reports, manuals, dissertations and other type of published or unpublished documents not found through bibliographical databases will be sought through:

-

websites of specialists and relevant organizations suggested by the workshop participants and questionnaire respondents (Table 4). Links or references to relevant publications will be searched. If publications of interest are not openly available, a copy will be requested to the organization representatives;

Table 4 Websites of specialist organisations and sources for grey literature -

past evidence syntheses of topics relevant to the research question from which any relevant publications not previously identified will be included in the list of references; and,

-

online databases holding collections of grey literature (Table 4).

Searches within specialist websites or grey literature online databases will need a smaller selection of key terms and search strings will be simplified as these sources are often limited by their search functions. Also, for these sources, searches will be made on the full text of the document. The final terms used for each source of grey literature will be recorded in the report of the systematic map.

Despite the effort to include sources of evidence from grey literature in the review process to reduce bias in the results obtained and access relevant evidence that may otherwise be ignored [4, 6], the number and type of grey literature consulted will be limited and biased to a degree by recommendations given by project partners and stakeholders, the geographical regions represented in the online databases for grey literature, or the number of documents available in English.

Article screening and study eligibility criteria

Searched articles will be subject to evaluation by a defined screening process and eligibility criteria set for study inclusion or exclusion from the evidence synthesis. This process has been established to gather the evidence that will best address the research question of interest for the present systematic map. Therefore, in an effort for avoiding bias, decisions regarding the inclusion or exclusion of the articles have been defined independently from any interest of inclusion of articles authored by reviewers. In the event of such articles being retrieved, screening will be delegated to other review team members.

Screening process

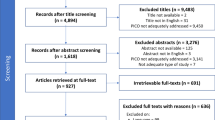

The results from the database searches will be transferred to the reference management software EndNote [36] and duplicates will be removed. At this stage, an initial selection will be carried out to extract only primary studies containing the population terms ‘tomato*’ or ‘lycoper*’ in the title or the abstract. The resulting set of papers will then be subject to a title screening, followed by an abstract examination of those considered ‘relevant’ or ‘doubtful’ following title scrutiny. The title and abstract screening will be performed by at least two reviewers. To avoid bias and ensure criteria consistency between reviewers, a random set of 100 papers will be screened at the title and abstract level. In case of differences in the assessment between reviewers, criteria for inclusion will be revised and clarified. Each article considered potentially relevant after these two stages will then be examined at the full text level. Similarly to the consistency test for title and abstract screening, a consistency test will be taken amongst reviewers for full text screening. A random set of 10% of the papers retained after the title and abstract screening, with a maximum of 50, will be screened at the full text level by each reviewer and any assessment inconsistencies between reviewers will be revised and resolved for consistency check. Publications found outside established bibliographic databases will be incorporated at this last screening stage. The screening process will be recorded and the number of excluded articles and reasons for exclusion at each stage will be provided in the Systematic Map report. Reasons considered for exclusion are listed in Additional file 5 and are directly related with the PICO components of the research question and the eligibility criteria described in the following sections. The use of software will be considered to help recording the decisions made during the screening and the meta-data extraction, e.g. CADIMA [37] and Colandr [38]. In case of uncertainty during the full text screening process, studies whose relevance is doubtful will be evaluated by the full review team.

Eligibility criteria

The search strategy will retrieve an extensive number of studies not relevant to the formulated question. For this, a series of criteria have been formulated to help a consistent assessment for the inclusion and exclusion of studies from the review set. By establishing these criteria, we also provide of a reproducible methodology, and aid an efficient screening process for the systematic map.

Relevant subject of study (population)

This systematic map will only include those studies where commercial tomato production is the subject of the research; no other vegetable or crop plants observations will be considered. Possible evidence given on tomato plants that are not for commercial use will be removed.

The studies included will not be geographically restricted. Nonetheless, specialist organisations and websites consulted will be subject to recommendations from European based stakeholders and project partners, which may somewhat limit the global coverage of testimonies retrieved from the grey literature.

Relevant types of intervention (also exposure or occurrence)

Techniques and management interventions that improve the use of water, N and/or P resources under field conditions will be the focus of synthesis of this systematic map. For this, all studies providing evidence of the effects of a technique, treatment or management on use-efficiency of either water, N, P or combinations of these, will be included. These can be strategies that influence tomato production under water- or/and N- and/or P-deficient circumstances or use-efficiency of these resources. Those studies where the measure of exposure or occurrence is not directly related to water, N or P use, will be excluded (e.g. salinity tolerance or waterlogging—where water and/or N and/or P deficiency is brought-about by other stressors).

This systematic map will only consider studies that explicitly mention that observations are from tomato crops grown in open field conditions. Therefore, those studies that report any water or nutrient use-efficiency strategies under controlled or protected conditions, such as in greenhouses or polytunnels, hydroponics or other forms of controlled-environment conditions which do not test intervention effects in the field will be automatically excluded.

Relevant types of comparators

The comparators that will be considered relevant for evidence synthesis are those that refer to the current practices previous to the introduced intervention of study. These can be either old, conventional or standard practices that differ from the intervention of study in that they do not aim to improve tomato productivity under water- or/and N- or/and P-deficit stress or by enhancing the use-efficiency of this resources.

Relevant types of outcomes

The type of outcome that will be valid for the systematic map will be the effect that interventions have on tomato productivity measured as yield. Studies will be accepted for inclusion if they expressly give measures of yield, which can be expressed either by fruit number or weight. Those studies reporting only the effects on other marketable outcomes different from productivity per se, such as quality or nutrition properties, will be excluded. Nonetheless, information on other marketable outcomes that may be reported by studies will not be ignored when discussed in relation to productivity outcomes and it will be extracted as variables in the evidence synthesis.

Relevant types of study

Primary experimental, quasi-experimental or observational studies or secondary studies that collate them. Only those studies that describe a specific research method or report on new empirical or observational evidence of an (intervention) effect will be included. Or, in the case of secondary studies, studies that collate evidence/data of these type of works will be accepted. Further description of the types of studies that will be acceptable is provided given in Additional file 5.

Language

The systematic map will only cover studies published in English due to time and resource limitation capacities of the review team. However, the English language is acknowledged to be the most commonly used in scientific literature, and that it will gather the largest body of published literature on the topic of this study.

Data coding strategy

Data coding will be extracted at the full text screening stage. These will correspond to different categories set by coding structures and variables therein that describe the literature meta-data. The meta-data will be extracted by populating options (variables) within a specifically designed questionnaire and will be included in a final database. Since, the questionnaire will be built using a random subset of studies (1%, minimum of 25) which will serve as initial examples from which to identify the appropriate questions and mechanisms of the questionnaire. From this, an initial set of important coding variables will be defined for the meta-data extraction and from which consistency amongst reviewers will be tested.

The meta-data gathered will be queried to synthesise the nature of the literature screened and so its capacity to address the systematic map question. Variables not directly related with the study intervention or treatment, but which are measured during the study and could influence the outcomes of the intervention (e.g. temperature or precipitation), will be extracted whenever available. However, those that are not systematically reported during the length of the study and which are from statistical geographical nature (e.g. mean annual temperature of the study site, annual/seasonal precipitation of the area or other geographical statistics), will not be extracted as they will be accounted by the geographical information that will be extracted.

The final coding of variables used in the meta-data extraction questionnaire will be elaborated during the processing of the subset of studies from the meta-data extraction pilot study and will be defined in additional file of the Systematic Map report. However, some descriptors have been identified in advance which will form the basis of the final variable codes (Additional file 5). Data coding will fall into the following categories: (1) bibliographic information (e.g. publication type, authors, time of publication, journal, country of authorship); (2) basic information of the study (e.g. region or country of assessment, geographic coordinates, farm type, soil type, temperature and precipitation during the vegetation period, duration of the assessment); and (3) properties of the interventions assessed (e.g. type of intervention, methodology of the study, stressor(s) assessed). Details on the internet searches will also be reported to enable reproducibility (e.g. URL, date of the search, full search string and search terms, and the number of search hits). Citations will be saved in standardised tag format Research Information System (RIS) files to allow the citation data to be readily available to ensure transparency and for future use. Information related to the meta-data extraction procedure will be coded (e.g. record ID, publication ID, date of the search, full search with the search terms used, date of the data extraction). Recording the nature of the intervention outcomes (positive, negative or neutral effects) from each study will also be considered. In that event, records from these will not be used to address any interpretation of the effectiveness of the interventions, and the limitations associated with the use of these data will be specifically stated in the Systematic Map report. A codebook that collates the variables and that will serve to define the coding structure as a basis for the meta-data extraction, is provided in Additional file 5.

Extraction of the coding information will take place during the full text screening, although general information on properties associated with the techniques or management approaches evaluated by each study will be extracted at the title and abstract stage (see Additional file 5). The meta-data extraction and coding will be carried at least by two reviewers. To ensure consistency amongst reviewers, a consistency check will be done as for the consistency tests at the screening process. For this, reviewers will populate the designed meta-data extraction questionnaire with the meta-data out from the papers retained after the consistency test at full text screening. Resulting data coding by each reviewer will be compared and any doubts and differences encountered will be clarified and the resolved procedure agreed. Additionally, an assessor from the review team will review a different random set of 10% of the studies being assessed by each reviewer, with a maximum of 50 per reviewer, to assure the quality of the meta-data extraction process.

Study validity assessment

This evidence synthesis has limited scope for assessing the validity of studies. Information on the study design and the comparators used will be collected as part of the coding extraction strategy (e.g. type of data collected, sample size, duration of study…) whenever possible. Mapping these against intervention variables may allow some comparisons on the nature of the evidence base for the different interventions. However, caution will be taken to ensure that the type and frequency by which the various interventions are collated in the Systematic Map will not provide indications as to the confidence on the effect of any one particular type of intervention (Additional file 6).

Study mapping and presentation

The outcomes from the systematic mapping exercise will be collated in a Systematic Map report, which will describe the different stages of the synthesis process and the evidence base addressing the research question formulated in this protocol. The map of results will be presented in the form of a database where studies accepted for synthesis will be collated with associated coding variables. Elaboration of figures, ‘heatmaps’ or other forms of spatial and visual maps will be considered to present meaningful results out from the systematic map outcomes. The report will provide a statistical summary of the characteristics of the studies found and a synthesis of the general trends. Clustering analysis of the coded data will help identifying possible knowledge gaps, for potential subtopics of interest in further primary search, and knowledge gluts, for potential subtopics of interest for full-synthesis systematic reviews. Information gathered in the systematic map will depend on the results obtained, but we can assume this will include information such as the indicators used to measure the strategies tested to help maintain tomato productivity under conditions of water-, N- and/or P-deficiency. Also, which strategies have been assessed to a greater and lesser extents, regions or countries where meta-data is most concentrated or insufficient, and the scale of available evidence on multiple- or combined-stress tolerance of tomato. As part of the Systematic Map report, a ROSES Flow Diagram for Systematic Maps will summarise the number of articles retrieved and excluded at each stage of the process, and the latter will extend to include a list of the reasons for exclusion. The database detailing meta-data included in the systematic map synthesis will be provided as additional file.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Roberts L. 9 billion? Science. 2011;333(6042):540–3.

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population prospects: the 2017 revision, key findings and advance tables. 2017; Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP/248.

Eurostat. Agri-environmental indicator—ammonia emissions. Eurostat: Statistics Explained. 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Agri-environmental_indicator_-_ammonia_emissions. Accessed 27 Mar 2019.

Min J, Lu K, Sun H, Xia L, Zhang H, Shi W. Global warming potential in an intensive vegetable cropping system as affected by crop rotation and nitrogen rate. CLEAN Soil Air Water. 2016;44(7):766–74.

Cordell D, Rosemarin A, Schröder JJ, Smit AL. Towards global phosphorus security: a systems framework for phosphorus recovery and reuse options. Chemosphere. 2011;84(6):747–58.

Morison JIL, Baker NR, Mullineaux PM, Davies WJ. Improving water use in crop production. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2007;363(1491):639–58.

Freydank K, Siebert S. Towards mapping the extent of irrigation in the last century: time series of irrigated area per country. Frankfurt Hydrology Paper 08, Institute of Physical Geography, University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. 2008.

Wisser D, Fekete BM, Vörösmarty CJ, Schumann AH. Reconstructing 20th century global hydrography: a contribution to the Global Terrestrial Network-Hydrology (GTN-H). Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2010;14(1):1–24.

Lavalle C, Micale F, Houston TD, Camia A, Hiederer R, Lazar C, Conte C, Amatulli G, Genovese G. Climate change in Europe. 3. Impact on agriculture and forestry. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2009;29(3):433–46.

Keeney DR. Sources of nitrate to ground water. In: Developments in agricultural and managed forest ecology. Vol. 21. Elsevier; 1989. pp. 23–34.

Sainju UM. Determination of nitrogen balance in agroecosystems. MethodsX. 2017;4:199–208.

Conley DJ, Paerl HW, Howarth RW, Boesch DF, Seitzinger SP, Havens KE, Lancelot C, Likens GE. Controlling eutrophication: nitrogen and phosphorus. Science. 2009;323(5917):1014–5.

Heuvelink E. Tomatoes. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 2005.

Martínez-Blanco J, Muñoz P, Antón A, Rieradevall J. Assessment of tomato Mediterranean production in open-field and standard multi-tunnel greenhouse, with compost or mineral fertilizers, from an agricultural and environmental standpoint. J Clean Prod. 2011;19(9–10):985–97.

Marcelis LFM, Dieleman JA, Boulard T, Garate A, Kittas C, Buschmann C, Brajeul E, Wieringa G, de Groot F, van Loon A, Kocsanyi L. CLOSYS: closed system for water and nutrient management in horticulture. In: III international symposium on models for plant growth, environmental control and farm management in protected cultivation. 2006; 718. pp. 375–82.

Eurostat. The fruit and vegetable sector in the EU—a statistical overview. Eurostat: Statistics Explained. 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/The_fruit_and_vegetable_sector_in_the_EU_-_a_statistical_overview#Fresh_vegetables:_holdings.2C_areas_and_production. Accessed 25 Mar 2019.

Atherton J, Rudich J. The tomato crop: a scientific basis for improvement. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1986.

Kimura S, Sinha N. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum): a model fruit-bearing crop. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2008;3(11):pdb-emo105.

Kubota C, McClure MA, Kokalis-Burelle N, Bausher MG, Rosskopf EN. Vegetable grafting: history, use, and current technology status in North America. HortScience. 2008;43(6):1664–9.

Lee JM, Kubota C, Tsao SJ, Bie Z, Echevarria PH, Morra L, Oda M. Current status of vegetable grafting: diffusion, grafting techniques, automation. Sci Hortic. 2010;127(2):93–105.

Djidonou D, Gao Z, Zhao X. Economic analysis of grafted tomato production in sandy soils in northern Florida. HortTechnology. 2013;23(5):613–21.

Chauhan H, Bagyaraj DJ, Selvakumar G, Sundaram SP. Novel plant growth promoting rhizobacteria—prospects and potential. Appl Soil Ecol. 2015;95:38–53.

Pandey SK, Nookaraju A, Upadhyaya CP, Gururani MA, Venkatesh J, Kim DH, Park SW. An update on biotechnological approaches for improving abiotic stress tolerance in tomato. Crop Sci. 2011;51(6):2303–24.

Meena VS, Meena SK, Verma JP, Kumar A, Aeron A, Mishra PK, Bisht JK, Pattanayak A, Naveed M, Dotaniya ML. Plant beneficial rhizospheric microorganism (PBRM) strategies to improve nutrients use efficiency: a review. Ecol Eng. 2017;107:8–32.

Blum A. Drought resistance, water-use efficiency, and yield potential—are they compatible, dissonant, or mutually exclusive? Aust J Agric Res. 2005;56(11):1159–68.

Passioura J. Increasing crop productivity when water is scarce—from breeding to field management. Agric Water Manag. 2006;80(1–3):176–96.

Istat. Agriculture. crops: fresh vegetables. 2017. http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=33703&lang=en#. Accessed 31 Mar 2019.

Ukrstat.org. State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Statistical yearbook—crop production of Ukraine. 2017. https://ukrstat.org/en/druk/publicat/kat_e/publ4_e.htm. Accessed 31 Mar 2019.

MAPA (Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food). Estadísticas agrarias: Agricultura -Superficies y producciones anuales de cultivos. Datos Avances de Hortalizas año 2017. 2017. https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/estadistica/temas/estadisticas-agrarias/agricultura/superficies-producciones-anuales-cultivos/. Accessed 31 Mar 2019.

INS (National Institute Statistics of Romania). Statistical yearbooks of Romania. 2016. http://www.insse.ro/cms/en/content/statistical-yearbooks-romania. Accessed 31 Mar 2019.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica - Statistics Portugal. Agriculture, forestry and fishing. 2017. https://ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=ine_tema&xpid=INE&tema_cod=1510. Accessed 23 Jan 2019.

Savvas D, Akoumianakis K, Karapanos I, Kontopoulou CK, Ntatsi G, Liontakis A, Sintori A, Ropokis A, Akoumianakis A. Recharging Greek Youth to Revitalize the Agriculture and Food Sector of the Greek Economy. Final report, sectoral study 5, vegetables: open-field and greenhouse production. 2015. https://www.generationag.org/assets/site/public/nodes/1019/1055-Vegetables_Open-Field_and_Greenhouse_Production.pdf. Accessed 31 Mar 2019.

Rosenstock TS, Lamanna C, Chesterman S, Bell P, Arslan A, Richards M, Rioux J, Akinleye AO, Champalle C, Cheng Z, Corner-Dolloff C, Dohn J, English W, Eyrich A, Girvetz EH, Kerr A, Lizarazo M, Madalinska A, McFatridge S, Morris KS, Namoi N, Poultouchidou A, Ravina da Silva M, Rayess S, Ström H, Tully KL, Zhou W. The scientific basis of climate-smart agriculture: A systematic review protocol. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security. CCAFS Working Paper No. 138. 2016.

CEE Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. Guidelines and standards for evidence synthesis in environmental management. Version 5.0. In: Pullin AS, Frampton GK, Livoreil B, Petrokofsky G, editors. 2018. http://www.environmentalevidence.org/information-for-authors. Accessed 30 Oct 2018.

CREBP. Centre for research in evidence-based practice. SRA systematic review assistant—deduplication module. Bond University. 2018. http://crebp-sra.com. Accessed 21 June 2018.

EndNote. EndNote X8 for Windows & Mac. Clarivate analytics. 2016.

Kohl C, McIntosh EJ, Unger S, Haddaway NR, Kecke S, Schiemann J, Wilhelm R. Online tools supporting the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and systematic maps: a case study on CADIMA and review of existing tools. Environ Evid. 2018;7:8.

Cheng SH, Augustin C, Bethel A, Gill D, Anzaroot S, Brun J, DeWilde B, Minnich RC, Garside R, Masuda YJ, Miller DC, Wilkie D, Wongbusarakum S, McKinnon MC. Using machine learning to advance synthesis and use of conservation and environmental evidence. Conserv Biol. 2018;32(4):762–4.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the expert workshop held in October 2018 hosted by the University of the Balearic Islands (UIB, Spain) and Paola Colla (University of Turin, UNITO) for logistical support.

Funding

The work presented in this paper was conducted as part of the EU TomRes project, which has received funding from the European’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement no. 727929.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NQ jointly with GB and PI conceived the study. PI and GB secured the financial support. NQ and GB presented the mapping methodology. NQ developed the search strategy, built the test library and will coordinate the mapping process, analysis and presentation of the results. NQ will implement the search and screen the articles with the contribution of the review team. NQ, GB, PI and FT drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1.

Expert consultation, workshop and list of participants. Summary of the specialist workshop held in Mallorca (Spain) in October 2018. Information on workshop participants, discussions held, and feedback given by specialists that helped framing the aims and scope of the systematic map and consultation over the methodology progress.

Additional file 2.

List of publications in the ‘test-list’ library. List of 47 published articles and other key literature relevant to the research question. Built by specialist’s recommendations and reviews citations, this list was used to test the candidate search terms adequacy during the scoping study for search terms and strings.

Additional file 3.

Scoping search terms and search string. This spreadsheet contains the different steps during the scoping study for identifying most suitable search terms and strings. The different sheets include the results from word frequency analysis with CREBP online tool, exploration of best-fit-for-purpose search terms and strings, results from the ‘test-list’ library checks and final strings.

Additional file 4.

Comparison and selection of Subject Categories for bibliographical databases. Lists and comparison of the subject categories or research areas by which subjects are categorised in the different bibliographical database sources consulted. Comparison between the subject categories from the different database sources allowed to identify common and equivalent categorisation for the selection of relevant subjects in the literature search.

Additional file 5.

Codebook variables and properties. Contains different aspects of the article screening and study eligibility criteria and the data coding strategy: 1. Reasons for exclusion during the screening process; 2. Codebook and drop-down list for initial coded variables considered for mapping; 3. Categorised types and subtypes of intervention approaches likely to find from retrieved literature; 4. Definition of the types of studies accepted; and 5. List of countries and several statistical information related with each country (e.g. geographical region, representation within bibliographical databases, tomato and vegetable production statistics, use of fertiliser, rainfall, irrigation and other economic variables).

Additional file 6.

ROSES form for Systematic Map Protocols. List of reporting standards for systematic map protocols and descriptive guidance to help the review authors to ensure all relevant methodological information is reported and to help editors and peer-reviewers to evaluate the reliability and validity of the review.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Quesada, N., Iannetta, P.P.M., White, P.J. et al. What evidence exists on the effectiveness of the techniques and management approaches used to improve the productivity of field grown tomatoes under conditions of water-, nitrogen- and/or phosphorus-deficit? A systematic map protocol. Environ Evid 8, 26 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-019-0172-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-019-0172-4