Abstract

Background

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) commonly causes hospitalization, particularly for individuals disproportionately impacted by structural racism and other forms of marginalization. The optimal approach for engaging hospitalized patients with AUD in treatment post-hospital discharge is unknown. We describe the rationale, aims, and protocol for Project ENHANCE (ENhancing Hospital-initiated Alcohol TreatmeNt to InCrease Engagement), a clinical trial testing increasingly intensive approaches using a hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation approach.

Methods

We are randomizing English and/or Spanish-speaking individuals with untreated AUD (n = 450) from a large, urban, academic hospital in New Haven, CT to: (1) Brief Negotiation Interview (with referral and telephone booster) alone (BNI), (2) BNI plus facilitated initiation of medications for alcohol use disorder (BNI + MAUD), or (3) BNI + MAUD + initiation of computer-based training for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT4CBT, BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT). Interventions are delivered by Health Promotion Advocates. The primary outcome is AUD treatment engagement 34 days post-hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes include AUD treatment engagement 90 days post-discharge and changes in self-reported alcohol use and phosphatidylethanol. Exploratory outcomes include health care utilization. We will explore whether the effectiveness of the interventions on AUD treatment engagement and alcohol use outcomes differ across and within racialized and ethnic groups, consistent with disproportionate impacts of AUD. Lastly, we will conduct an implementation-focused process evaluation, including individual-level collection and statistical comparisons between the three conditions of costs to providers and to patients, cost-effectiveness indices (effectiveness/cost ratios), and cost–benefit indices (benefit/cost ratios, net benefit [benefits minus costs). Graphs of individual- and group-level effectiveness x cost, and benefits x costs, will portray relationships between costs and effectiveness and between costs and benefits for the three conditions, in a manner that community representatives also should be able to understand and use.

Conclusions

Project ENHANCE is expected to generate novel findings to inform future hospital-based efforts to promote AUD treatment engagement among diverse patient populations, including those most impacted by AUD.

Clinical Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT05338151.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Contributions to the literature

-

Acute medical hospitalization may be an important setting for providing treatment of untreated alcohol use disorder (AUD), particularly for those at greatest risk for adverse consequences of AUD;

-

The optimal strategy for engaging patients with untreated AUD to promote engagement in treatment post-hospital discharge is currently unknown;

-

Brief Negotiation Interview with facilitated initiation of medications for AUD and initiation of computer-based training for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT4CBT) is expected to be an effective strategy for promoting AUD treatment engagement post-hospital discharge;

-

Data regarding factors relevant for initiating AUD treatment in the hospital setting are needed to inform real-world implementation: this should be facilitated by data collected at the individual level and analyzed statistically comparing costs and cost-effectiveness of in-hospital AUD treatment strategies.

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality [1], yet typically left untreated [2]. Among the 29.5 million adults with AUD in 2021, only 4.6% had received any treatment (i.e., behavioral or medication) in the past year and less than 2% took a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medication for AUD (MAUD) [2]. Structural racism—the totality of ways racism is pervasively and deeply embedded in systems, laws, and written or unwritten policies—and related social determinants of health (SDOH, e.g., inequitable access to education; food insecurity; and discrimination) that are enacted through markers of race and ethnicity may drive alcohol use and interfere with access to and potential benefits of AUD treatment on multiple levels (Fig. 1). Extant research has demonstrated that AUD prevalence and treatment rates differ across racial and ethnic groups and these differences may be the direct result of structural racism and SDOH [3, 4]. Strategies in relevant “touchpoints” are needed that overcome barriers imposed by structural racism and SDOH to address AUD across populations, particularly minoritized racial and ethnic populations.

Acute medical hospitalization may provide such an untapped opportunity to link diverse individuals with AUD to treatment [5]. First, alcohol-associated hospitalizations are common [6, 7] and represent a “reachable moment” when a range of behavioral and medication-based treatments may be initiated and supported by multidisciplinary hospital-based clinicians and staff [8, 9]. Second, hospitalization may offer a unique opportunity to reach minoritized racial and ethnic populations as they have greater rates of alcohol-related hospitalizations relative to White individuals [10], and, importantly, are less likely to receive routine care elsewhere [11]. Third, patients may be introduced to evidence-based digital interventions to address AUD [12] that could continue upon hospital discharge and address barriers to treatment (e.g., variability in community-based access to behavioral health treatment).

To date, few studies have sought to identify the optimal strategy for linking patients to AUD treatment during acute hospitalization [5, 13]. Though prior studies have focused on evaluating different medication treatment options [14,15,16,17,18,19], to our knowledge, no studies have compared the impact of brief counseling interventions with the addition of MAUD with and without digital interventions to promote post-hospitalization treatment engagement among all individuals with AUD. Also, no studies have focused on understanding differential effectiveness of treatment engagement strategies across racialized and ethnic groups who experience enhanced adverse impacts of AUD and have unique barriers to AUD treatment. To address this important gap, we are conducting Project ENHANCE (ENhancing Hospital-initiated Alcohol TreatmeNt to InCrease Engagement), a three-arm randomized clinical trial with a hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation approach that also reports and statistically compares between conditions the provider and patient costs, indices of cost-effectiveness, and indices of cost–benefit with attention to the role of systemic racism.

Methods

Overall design

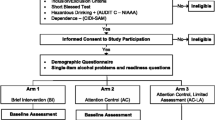

Funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Project ENHANCE is a three-arm randomized clinical trial that aims to enroll a diverse sample of individuals with untreated AUD (n = 450) during their acute medical hospitalization at a large urban hospital in the US northeast. We will compare the effectiveness of three treatment engagement strategies on the primary outcome of AUD treatment engagement at the 34th day post-hospital discharge (Aim 1, Fig. 2): (1) Brief Negotiation Interview (with referral and telephone booster) alone (BNI), (2) BNI plus facilitated initiation of MAUD (BNI + MAUD), or (3) BNI + MAUD + initiation of computer-based training for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT4CBT, BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT). Secondary outcomes include AUD treatment engagement on the 90th day post-hospital discharge and changes in self-reported alcohol use (percentage of heavy drinking days by Timeline Followback) and the alcohol biomarker, phosphatidylethanol (PEth). Exploratory outcomes based on self-report and the electronic medical record include health care utilization, such as emergency department visits and hospital readmission. We will additionally explore whether the effectiveness of the interventions on AUD treatment engagement and alcohol use outcomes differ across and within racialized and ethnic groups based on SDOH (Aim 2). In parallel and consistent with a hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation approach [20], we will conduct an implementation-focused process evaluation [21] that includes costs, cost-effectiveness, and cost–benefit analyses comparing the three intervention combinations (Aim 3).

Project ENHANCE Protocol Overviewa. a. All participants regardless of treatment conditions also receive telephone booster at 2 weeks. AUD alcohol use disorder; BNI brief negotiation interview; MAUD medications for alcohol use disorder; CBT4CBT computer-based training for cognitive behavioral therapy

To ensure that a range of perspectives inform the study design and protocol implementation, our study team is intentionally diverse based on training (psychologists, inpatient and outpatient-based Addiction Medicine and Addiction Psychiatry physicians, health services researchers with health equity focus); race and ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and White); gender; immigration status; sexual orientation; and lived experience with family and/or friends impacted by AUD.

Rationale for study design

Our study design is informed by several key principles. First, while addiction screening and treatment is increasingly being provided in hospital settings, this is not uniformly done utilizing evidence-informed care by trained medical personnel. The optimal strategy to promote engagement in AUD treatment post-hospitalization is not known. This is of particular concern for racial and ethnically minoritized individuals with AUD who are known to have worsening health disparities from alcohol use due to systemic inequities [3, 11, 22, 23]. Second, hospitalization may be an opportunity to minimize the impact of common drivers of health inequities and reach particularly vulnerable patient populations (e.g., individuals disproportionately impacted by structural racism and its manifestations, individuals experiencing houselessness) and others who may not access routine outpatient care. Since the mean length of a hospital stay for a patient with a principal alcohol-related disorder is nearly 5 days [24], there is a potential opportunity to engage patients in various treatments without the challenges (e.g., transportation) in outpatient settings. Third, best practice recommendations for treating AUD include an evidence-based behavioral therapy, such as CBT, with MAUD [25]. Unfortunately, efforts to initiate these treatments together during acute medical hospitalization are lacking [26]. Fourth, access to high-quality CBT is limited in community treatment settings due to the cost of training and supervision required [27], but may be overcome by digitally-delivered approaches that seem inexpensive to deliver in hospital settings and serve to overcome barriers related to treatment availability [28, 29]; concerns of discrimination or stigma [30, 31]; and poverty and environmental violence that may impede in-person treatment engagement [32, 33]. CBT4CBT, is a proven, scalable platform for addressing AUD that is available in English and Spanish; does not require literacy or high levels of proficiency with computers or technology and can be readily delivered via tablets; and is beneficial across diverse populations offering a potentially useful strategy to help individuals with AUD develop necessary skills to reduce alcohol use post-hospital discharge [34, 35]. Fifth, there are limited data characterizing the prevalence of SDOH, many of which are indicators of structural racism, among patients hospitalized with AUD [36] and few studies have examined the moderating effects of racialized identity, ethnicity, and SDOH on AUD treatment outcomes [37]. Sixth, while there is growing interest in the alcohol biomarker phosphatidylethanol (PEth) for detecting unhealthy alcohol use [38], there is a lack of data on factors that impact PEth among medically complex patients in the context of acute illness [39]. Lastly, to inform future implementation efforts beyond the research context, it is important to collect data on factors that impact trial implementation guided by implementation science principles [20].

Study aims and hypotheses

Among 450 hospitalized individuals with untreated moderate to severe AUD (by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 [DSM-5] criteria), our aims are to evaluate the effectiveness of hospital-initiated BNI vs. BNI + MAUD vs. BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT on AUD treatment engagement at 34 days (primary outcome) and 90 days post-discharge; changes in alcohol use by self-report and biomarker over the 90 day period; and (exploratory) health care utilization, including Emergency Department visits and hospital readmission (Aim 1). We hypothesize that BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT will be more effective than BNI + MAUD, which will be more effective than BNI alone as evidenced by higher rates of AUD treatment engagement, and reductions in alcohol use and urgent and emergency healthcare utilization post-discharge.

We will explore whether the effectiveness of the interventions on AUD treatment engagement and alcohol use outcomes differs across and within racial and ethnic groups and by SDOH indicators that reflect sequalae of structural racism (Aim 2). We hypothesize that there will be no difference in treatment effectiveness by race or ethnicity after adjustment of confounders but there will be differences based on SDOH.

Consistent with our prior experiences [40], we will additionally conduct an implementation-focused process evaluation [21], involving process measures, a clinician and staff survey, in addition to obtaining measures of the amounts and unit costs of resources used to implement each intervention to patients as well as health care staff. Analyses of cost, cost effectiveness, possible cost-savings benefits from reduced use of health care following the intervention, and cost–benefit for each intervention will compare individual-level provider and patient costs, indices of cost-effectiveness, and indices of cost–benefit for the three intervention combinations, as well as intervention-level indices of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) [41, 42] (Aim 3).

Study context

The study is being conducted at Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH), a large, urban teaching hospital in New Haven, CT that includes two campuses serving a diverse patient population. For example, from July 1, 2022, to June 30, 2023, 1172 unique patients were admitted to a Medicine service at YNHH who had evidence of an alcohol-related diagnosis (based on clinical orders for Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment—Alcohol; AUDIT-C ≥ 7; and/or alcohol-related diagnosis). Among these patients, the mean age was 54 yo (standard deviation = 14.25) and the majority were men (67%). Fifteen percent identified as Hispanic or Latino and 27% as Black. YNHH uses the Epic® electronic medical record and has integrated tools to promote evidence-based AUD care, including Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) [43] screening prompts for all hospitalized patients and an AUD signature care pathway that is triggered for patients with evidence of a potential AUD. Hospital-based treatment services include Addiction Medicine specialty consultation care provided by the Yale Addiction Medicine Consult Service (YAMCS). This Service routinely recommends initiation of MAUD, facilitates outpatient referral, and is consulted for the minority of hospitalized patients with AUD who present with complex substance withdrawal and/or comorbid substance use disorders. All FDA approved MAUD, including injectable naltrexone, are available on the inpatient hospital formulary. Community-based treatment options for patients with AUD discharged from YNHH include a range of options for care by Addiction-certified physicians in specialty or office-based settings. Given formative work demonstrating inconsistent knowledge and adoption of evidence-based alcohol-related care among YNHH clinicians [44], we planned to conduct a clinician training prior to study launch.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

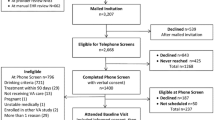

Recruitment and randomization

In collaboration with frontline clinicians, nursing staff, and YAMCS and Epic reports, potentially eligible participants are identified based on: (1) frontline clinician and staff referral; (2) identified with a proactive daily Epic generated report as having a documented Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA) for Alcohol score in the past 96 h, an AUDIT-C score ≥ 7 in the past 96 h, and/or an active AUD diagnosis on their problem list, and are hospitalized on a general medicine ward; (3) YAMCS team referral; and (4) recruitment handouts and flyers for patients admitted to the hospital. Upon confirmation from the primary care team that the patient is appropriate to approach for research, the research coordinator will approach the patient and obtain verbal permission to screen for eligibility. Individuals who have an AUDIT-C ≥ 7 will be assessed for presence of a moderate to severe AUD by the Alcohol Symptom Checklist[45, 46] followed by screening for ≥ 1 heavy drinking day, defined as any day of consumption of ≥ 5 standard drinks for men, and ≥ 4 standard drinks for women[47] in the 30 days prior to hospitalization. Individuals who are identified as meeting eligibility criteria, provide written informed consent to participate, and complete baseline assessments are randomized 1:1:1 using a computerized urn randomization program that balances probability of treatment condition based on: (1) race and ethnicity, (2) sex, (3) Spanish language preference, and (4) AUD severity [48, 49]. Randomized participants receive $75 gift card or a tablet computer (“tablet”) for completion of baseline assessments and an additional $50 gift card for completing each of the two follow-up assessments.

Data collection protocol

All data are collected through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) [50], the clinical trial management system. Screening and baseline assessments are collected by trained research coordinators to ensure participants meet eligibility criteria and to capture key predictor variables as well as potential moderators and mediators (Table 2). Follow-up assessments collect primary, secondary, and exploratory outcome data via participant assessments, electronic health record data, provider/facility confirmed treatment engagement, and biomarkers. The primary outcome of AUD treatment engagement on the 34th day following hospital discharge is consistent with the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) Initiation and Engagement with Treatment (IET) measure (i.e., ≥ 2 AOD services within 34 days of the initiation visit), specified by the National Committee on Quality Assurance. It is used nationally by health plans [51, 52] and the endpoint in clinical trials focused on promoting addiction treatment from acute care settings [53,54,55]. Type of treatment will be classified according to the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Criteria, verified by objective data (e.g., review of the electronic medical record, contact with the treatment facility, photo of oral naltrexone pill bottle) [56, 57]. Among those who report taking MAUD, we will assess MAUD type and self-reported adherence.

A secondary outcome of AUD treatment engagement is potential change in use and cost of health services from before the index hospitalization to a comparable period following hospital discharge. Reduction in health service use and costs would be a cost-savings outcome (i.e., benefit of the intervention) [58]. Even if these health service use and cost savings do not completely compensate for intervention costs, they could at least reduce net intervention cost. Emergency department, outpatient, and inpatient visits as well as medication before and after hospitalization will be extracted from the electronic health record for the 12 months before and following hospitalization. Intervention costs themselves will be assessed by multiplying provider and patient time spent for each patient in each intervention condition by provider and patient self-reported wage rates including employment perquisites, plus any materials, medication, and other resources used in interventions. These costs, and costs of computers and software used in CBT4CBT conditions will be assessed using methods developed in previous research published by several of the current authors [58].

Intervention components overview

Brief negotiation interview with telephone booster (BNI)

All participants receive the BNI with referral to aftercare AUD treatment and opportunity for a 2-week telephone booster delivered by a dedicated trained Health Promotion Advocate (HPA). The BNI contains the essential components of effective brief interventions [59,60,61,62,63,64] and includes training materials that have been used to train non-specialists in various clinical settings. First developed and evaluated in the YNHH Emergency Department (ED) [63,64,65], the purpose of the BNI is to assist patients in recognizing and changing levels of alcohol consumption that pose health risks. It relies on strategies from motivational interviewing (MI) and the stages of change model [66]. The main goals are to: (1) decrease ambivalence about reducing alcohol use; and (2) negotiate strategies for change. During the 15–20 min BNI, the HPA will: (1) Raise the subject of alcohol use; (2) Provide feedback: review the patient’s alcohol consumption, make a connection to the patient’s medical condition and reason for hospitalization; review guidelines for lower risk alcohol use; (3) Enhance motivation: via a readiness change ruler, which can assist in developing discrepancy; and (4) Negotiate and Advise: negotiate goal, provide feedback, ask patient to complete drinking agreement; summarize and arrange follow-up. Participants are provided a pamphlet regarding the impact of AUD on health and potential treatment resources (Additional files: 1, 2). The BNI session follows a structured encounter form and is digitally recorded for fidelity monitoring purposes. Consistent with our prior approaches [67, 68], the ED-based BNI manual was adapted by our team for relevance to racially and ethnically diverse hospitalized patients with AUD. All participants will be referred for formal AUD treatment per American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) criteria [57] prior to discharge for ongoing AUD treatment. For this trial, we considered this the “control” condition given that this is consistent with standard of care [69] and we anticipate our approach guided by an interdisciplinary team with diverse perspectives and expertise will bolster this standard.

Facilitated provision of MAUD

For participants randomized to either BNI + MAUD or BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT, the HPA provides education and counseling regarding MAUD as part of the BNI to the participant and communicates to the primary medical team that MAUD should be considered. Informed by existing resources and guidelines [70, 71], participants receive a pamphlet regarding MAUD (Additional files 1) and, via a note in the EMR, clinicians and staff are provided information regarding MAUD, including how to access the AUD treatment care signature pathway, with documentation of any stated preferences of the participant regarding a particular form of MAUD. Consistent with an effectiveness study, ultimate prescribing of any medication and the choice of medication is at the discretion of the primary medical team with the participant, and medications are provided via usual means.

CBT4CBT

For participants randomized to BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT, the HPA gives the participant a username and password to access the web-based program on a provided tablet or their own device and encourages the participant to begin accessing the modules during their hospitalization (Additional files: 1, 2). Participants may continue accessing the program after discharge from the hospital. Available in English and in a culturally-adapted, Spanish version [35], this highly secure seven module program is modeled closely after the evidence-based NIAAA CBT treatment manuals [72]. Eight independent randomized trials have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT4CBT at improving substance use outcomes across diverse settings and populations [34, 35, 73,74,75,76,77,78].

Intervention training and monitoring

Training of HPAs includes didactics and practice exercises in both: 1) MI and 2) the BNI and its components. The MI portion of the curriculum includes 2 half-day training sessions: 3 h of instruction, beginning with an introduction to the fundamentals of MI (i.e., MI spirit and technical skills) and evidence of its effectiveness on reduction of alcohol use [79,80,81,82]; and 3 h of skills-based practice exercises using medical setting patient-specific cases. Similarly, the BNI section of the curriculum includes 2 half-day training sessions: 3 h of instruction, beginning with guidance on the steps of the BNI and support of its use among patients presenting in medical settings [64, 83, 84]; and 3 h of skills-based practice exercises. The following sections describe the critical components and training processes of MI and the BNI implemented in preparing the HPAs.

Prior to beginning study activities, HPAs were individually trained over 4 half-day workshops by a licensed psychologist with extensive experience in MI (Table 3). After this, the HPA demonstrated their acquired BNI skill with a final patient case. The patient case portion of the curriculum took 30 min. The case was specific to the study patient population and setting. The trainer was the patient actor and directly observed the implementation of the BNI. Feedback was provided at the time of the encounter. As indicated, to gain comfort and skills with working in the hospital setting and the outpatient AUD treatment referral network, the HPA additionally spent 2 days shadowing existing hospital-based HPAs who work in conjunction with YAMCS.

Adapted from the ED-based BNI manual [53, 65], the HPAs are provided with the Project ENHANCE intervention manual, structured encounter forms, and patient-facing pamphlets. The BNI session is audio recorded and reviewed periodically by a clinical psychologist to ensure fidelity to the intervention using a checklist (Additional file: 2) and feedback is provided at least weekly. Further, the HPAs are provided the opportunity to participate in a monthly teleconference with study investigators to reflect on experiences with delivering the intervention and intervention fidelity, with particular attention to considerations on how best to address SDOH and structural racism in the context of the BNI.

Costs of training and subsequent validation via demonstration included trainer and HPA time and materials. These costs were divided among the number of participants receiving interventions, plus the additional number of participants who could have received interventions from trainees over the subsequent year(s).

Statistical considerations

Justification of sample size

Power for the three-arm trial was estimated based on an alpha of 0.025, which is a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, given three treatment conditions with two planned contrasts. We assumed a 40% base rate in engagement in AUD treatment at 34-days post-discharge (primary outcome) following BNI based on our YAMCS post-discharge data and published reports from other hospital-based addiction medicine consult services [13]. A sample size of 450 (150 per condition) will provide adequate power (> 80%) to detect a 15% increase in engagement from the comparator treatment (BNI + MAUD or BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT) at 34-days, consistent with a small to medium effect (delta = 0.34). With a sample size of 360 participants (120 per condition), we would have > 80% power to detect a 20% increase in engagement, consistent with a medium effect (delta = 0.46). Thus, with a randomized sample of 450, we will have adequate power to detect a medium effect on AUD treatment engagement, assuming a 20% loss of data at follow-up. This is based on experiences with similar populations at YNHH [65], as well as those in our prior outpatient treatment studies [34, 74, 76].

Statistical analyses

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary objective of this analysis will be to determine if the proportion of participants with formal AUD treatment engagement (yes/no) at 34 days post-discharge differs among those randomized to BNI alone, BNI + MAUD, and BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT in this diverse sample. The primary outcome (1a) of AUD treatment engagement is binary and we will use logistic regression with two planned contrasts to evaluate statistical significance of the differences in proportion of formal AUD treatment engagement (as verified through electronic medical record and/or contact with treatment facility). This statistical model will also be used to assess efficacy of study interventions on AUD treatment engagement at 90-days following randomization (1a). Secondary outcomes (1b) will include change in the self-reported percentage of heavy drinking days (PHDD) by month from the 30-day period prior to hospitalization (baseline) to the 34- and 90-day post-discharge timepoint, which will be evaluated with random effects regression statistical models. These models have several advantages in follow-up data from clinical trials of individuals who use substances, as they are less vulnerable than traditional MANOVA approaches to missing data [85, 86]. An additional secondary outcome will include change in biomarker PEth, which as a continuous outcome will be evaluated with a similar statistical approach. Given limited data on factors impacting PEth levels among hospitalized patients [87] and building from our own experiences [88], we will also evaluate the correlation between baseline self-reported alcohol use (in the 30-day period prior to hospitalization) and PEth levels (e.g., liver disease, hemoglobin [38]), factors associated with PEth levels adjusting for baseline self-reported alcohol use, and factors impacting change in PEth from baseline to follow-up. Exploratory outcomes of healthcare utilization, including rates and costs of emergency department visits and hospital readmissions during the 34- and 90-day post-discharge period will be evaluated with mixed model ANOVAs. Analysis of treatment effects on primary, secondary, and exploratory outcomes will include the following contrasts: H1: BNI + MAUD > BNI; BNI + MAUD + CBT4CBT > BNI + MAUD or BNI.

Exploratory outcomes

The objective of these analyses are to explore differences in intervention effectiveness within and across racialized groups, ethnicity, and SDOH using the same outcomes as Aims 1. The standard approach to moderation using regression models that include a ‘treatment by race interaction’ variable has multiple pitfalls, including lack of consideration of within-group differences [89]. Thus, we will incorporate suggested alternatives less likely to lead to misleading findings [89,90,91]. These include examining the efficacy of a specific treatment within a racialized and/or ethnic minoritized group (e.g., is BNI + MAUD significantly more effective than BNI for Black individuals?) as well as evaluating the efficacy of a specific treatment across different racialized and/or ethnic groups (e.g., are there significant differences in AUD treatment engagement for BNI + MAUD between Black and White individuals?). These analyses will be conducted with similar statistical approaches as Aim 1 (i.e., logistic regression for engagement outcomes, random effects regression for change in alcohol use outcomes). Furthermore, it is important to consider why specific treatments might yield more favorable results within or between certain racialized or ethnic groups. Accordingly, and informed by the Socio-Ecological Model (Fig. 1), we will evaluate SDOH as key moderators of intervention effects on AUD treatment engagement and alcohol use post-discharge. In these models, logistic regression will be used to examine the effect of the interaction of multiple individual-level SDOH (for example employment, education, housing instability, food insecurity, transportation insecurity, medical mistrust, discrimination experiences) by treatment condition on AUD treatment engagement post-discharge. We will also examine individual-level SDOH as a latent variable in Structural Equation Models evaluating the impact as a moderator of treatment effectiveness on post-discharge engagement and alcohol use outcomes.

Implementation-focused process evaluation

Informed by work of others [21] and our own experiences [40, 92], we will conduct an implementation-focused process evaluation to gain an understanding of the necessary factors for building the infrastructure for this clinical trial, delivering the associated interventions in the hospital setting, and then potentially sustaining the interventions outside the context of a funded study. We will ground our evaluation in RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) with particular attention to promoting health equity [93,94,95]. To achieve these goals, data sources complementing participant assessments will include screening and enrollment logs (e.g., reasons patients decline study participation); recordings from intervention sessions; minutes from study team meetings; time, transportation, and other resources that participants as well as the HPAs and other healthcare staff contribute to interventions; as well as patient satisfaction data collected as part of the follow-up assessments.

Intervention-level cost per engaged patient will be calculated, along with increments in this cost as successive interventions are added. We will conduct analyses to determine the type, amount, and monetary values (i.e., costs) of the major resources used to implement each intervention for each patient, including time of professionals and patients, medication, and other intervention materials and resources. Combining cost with effectiveness data for individual patients will make possible descriptive scattergrams and group-level graphs of effectiveness = f [costs] and benefits = f[costs] as well as statistical analyses comparing effectiveness/cost ratios (e.g., change in PHDD per $100 of resources consumed by intervention) and other indices of relationships between costs and effectiveness for patients in each intervention condition. Average and median effectiveness/cost will be compared statistically for each condition with individual-level effectiveness and costs [58]. Cost per effectively treated patient also will be calculated at the group level, defining effective treatment according to quantitative definitions of clinically meaningful change in alcohol use. Similar analyses will examine graphically and statistically cost–benefit relationships as expressed by individual-level net benefit (i.e., reduction following intervention in costs of ED and readmission minus costs of intervention) [58]. Further, building on a mixed-methods evaluation that informed the study protocol [44], we will conduct a survey of hospital-based clinicians and staff upon conclusion of the clinical trial regarding their perspectives on the alcohol treatment interventions and necessary supports to sustain delivery of these interventions outside of the research infrastructure. We will also capture factors that may contribute to inequitable care among historically minoritized racial and ethnic groups.

Ethical approval and protection of participants

This HIPAA-complaint study is approved by the Yale School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee (protocol #2000031874). The Data Safety and Monitoring Board will review enrollment, baseline characteristics of enrolled participants, intervention delivery, adverse events, and outcome ascertainment biannually starting approximately 6 months after enrollment initiation.

Current status of Project ENHANCE

In preparation for study launch, the Project ENHANCE team engaged a variety of hospital and university-based stakeholders to refine study processes and prepare for implementation. This led to the development of a multi-pronged approach to inform recruitment strategies. In addition, based on these discussions, the Project ENHANCE team offered a set of four 1-h conferences to hospitalist-based clinicians regarding the importance of providing alcohol treatment in the hospital setting, treatment options, unique factors impacting minoritized racialized and ethnic populations, and the study protocol with an emphasis on CBT4CBT. Continuing medical education credits (CME) were offered for attendance with the goal of providing basic education regarding the importance of addressing AUD in the hospital setting; considerations for providing care through an equity lens; considerations for prescribing MAUD among medically complex patients; and the evidence for CBT4CBT.

After completion of this series and trainings of study staff, Project ENHANCE opened for recruitment on September 13, 2022, and recruitment and follow-up are ongoing.

Discussion

Project ENHANCE will generate novel data on the comparative effectiveness of three different treatment strategies on promoting AUD treatment engagement and alcohol reduction post-hospital discharge among a diverse sample of patients with untreated AUD, with special emphasis on minoritized racial and ethnic patients. Our protocol is timely and highly relevant for several reasons. First, few prior studies have focused on the hospital setting to reach individuals with untreated AUD, though one important study focused on evaluating different formulations on naltrexone [14]. We build on this work by evaluating an intervention that is flexible with regards to the specific type and formulation of MAUD with ultimate prescribing at the discretion of the participant and primary team. Second, although there have been studies using digital interventions to address alcohol use in outpatient and emergency settings [96,97,98], to our knowledge, no studies have sought to initiate a robust digital treatment intervention to address AUD or any other substance use disorder in the inpatient hospital setting. Our trial will be amongst the first to evaluate the impact of the evidence-based CBT4CBT platform on AUD treatment engagement when initiated in the hospital setting [12, 26]. Third, our team’s diverse perspectives and expertise is unified by a commitment to promote health equity and address the role of structural racism as a driver of AUD and its consequences, as well as a barrier to treatment. We expect to generate new insights on the prevalence and correlates of SDOH among our sample of enrolled participants and the moderating effect of SDOH on intervention effects and outcomes, expanding beyond traditional measures of SDOH (e.g., housing status) [5]. Fourth, there is significant interest in complementing self-reported alcohol use with an alcohol biomarker, such as PEth [38], yet there have been few studies that collected PEth in the hospital setting. We anticipate examining the correlation between self-reported alcohol use and the biomarker PEth among patients experiencing acute illness and across clinically relevant subgroups [99] and its association with clinical measures over time (e.g., cognitive function). Lastly, given the hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation design, we hope to generate critical data including cost, cost-effectiveness, and cost–benefit, useful for informing future implementation of these different HPA-delivered treatment strategies in other large, urban health systems in diverse communities.

Limitations

We expect limitations to our study. First, our focus has been to address the role of race and ethnicity in all aspects of study design and implementation; however, we have not had a similar focus on the role of gender that should be considered in future work. Second, while the MAUD conditions intend to facilitate MAUD through provision of patient and clinician facing materials, this may not be sufficient to stimulate actual prescribing. Third, the ongoing challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic have had a significant impact on clinicians, including burnout; clinicians may be less motivated, prepared, and able to address AUD in these circumstances. Fourth, Addiction Medicine Consult Services are increasingly available in hospitals across the United States, yet this still represents the minority of hospitals. In addition, the study is being conducted in an academic hospital system in New Haven, CT, which offers a range of accessible services for AUD upon hospital discharge. Thus, findings may not be generalizable to contexts where AUD treatment services are not as robust, including community hospitals and other regions of the United States. Fifth, all participant-facing documents and the CBT4CBT platform are available in English and Spanish and our team’s Research Coordinators are all fluent in English and Spanish. However, consistent with common practice at YNHH, interventions delivered by the HPAs will require use of translation services for Spanish-only speaking patients due to the skills of our current team members. Lastly, due to resource constraints, research coordinators and the HPAs will not be blinded to study conditions; no team member, however, will have a priori knowledge about group assignment prior to randomization.

Conclusion

Project ENHANCE is expected to generate timely data to inform hospital-based practices on equitable strategies for promoting AUD treatment engagement and alcohol reduction among patients with untreated AUD to mitigate AUD-related morbidity and mortality.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets generated during the current study will be made available from the authors upon request and be made publicly available in a deidentified format consistent with NIAAA policies to the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive repository.

References

Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, Bohm MK, Liu Y, Lu H, Naimi TS. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among us adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2239485.

2021 NSDUH Detailed Tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-detailed-tables. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, Haozous EA, Withrow DR, Chen Y, de Gonzalez AB, Freedman ND. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1921451.

Collaborators GBDA. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2.

Englander H, King C, Nicolaidis C, Collins D, Patten A, Gregg J, Korthuis PT. Predictors of opioid and alcohol pharmacotherapy initiation at hospital discharge among patients seen by an inpatient addiction consult service. J Addict Med. 2020;14:415–22.

Singh JA, Cleveland JD. Trends in hospitalizations for alcohol use disorder in the US from 1998 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2016580.

Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2022942.

Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:296–303.

Makdissi R, Stewart SH. Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: a narrative review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8:11.

Sacco P, Unick GJ, Kuerbis A, Koru AG, Moore AA. Alcohol-related diagnoses in hospital admissions for all causes among middle-aged and older adults: trends and cohort differences from 1993 to 2010. J Aging Health. 2015;27:1358–74.

Zemore SE, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Mulia N, Kerr WC, Ehlers CL, Cook WK, Martinez P, Lui C, Greenfield TK. The future of research on alcohol-related disparities across U.S. racial/ethnic groups: a plan of attack. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79:7–21.

Kiluk BD, Ray LA, Walthers J, Bernstein M, Tonigan JS, Magill M. Technology-delivered cognitive-behavioral interventions for alcohol use: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43:2285–95.

Englander H, Dobbertin K, Lind BK, Nicolaidis C, Graven P, Dorfman C, Korthuis PT. Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: a propensity-matched analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2796–803.

NIH research Portfoli Online Reporting Tools (RePORT). Oral V Injection naltrexone in hospital: comparative effectiveness for alcoholism. https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm? aid=9539171&icde=53768896&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=1&csb=default&cs=ASC&pball=. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Busch AC, Denduluri M, Glass J, Hetzel S, Gugnani SP, Gassman M, Krahn D, Deyo B, Brown R. Predischarge injectable versus oral naltrexone to improve postdischarge treatment engagement among hospitalized veterans with alcohol use disorder: a randomized pilot proof-of-concept study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:1352–60.

Kirchoff RW, Mohammed NM, McHugh J, Markota M, Kingsley T, Leung J, Burton MC, Chaudhary R. Naltrexone initiation in the inpatient setting for alcohol use disorder: a systematic review of clinical outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5:495–501.

Terasaki D, Loh R, Cornell A, Taub J, Thurstone C. Single-dose intravenous ketamine or intramuscular naltrexone for high-utilization inpatients with alcohol use disorder: pilot trial feasibility and readmission rates. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2022;17:64.

Leung JG, Narayanan PP, Markota M, Miller NE, Philbrick KL, Burton MC, Kirchoff RW. Assessing naltrexone prescribing and barriers to initiation for alcohol use disorder: a multidisciplinary. Multisite Surv Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:856938.

Tigh J, Daniel K, Balasanova AA. Impact of hospital-administered extended-release naltrexone on readmission rates in patients with alcohol use disorder: a pilot study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022;24:43569.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50:217–26.

Hagedorn HJ, Stetler CB, Bangerter A, Noorbaloochi S, Stitzer ML, Kivlahan D. An implementation-focused process evaluation of an incentive intervention effectiveness trial in substance use disorders clinics at two Veterans Health Administration medical centers. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:12.

Zemore SE, Ye Y, Mulia N, Martinez P, Jones-Webb R, Karriker-Jaffe K. Poor, persecuted, young, and alone: toward explaining the elevated risk of alcohol problems among Black and Latino men who drink. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:31–9.

Ransome Y, Carty DC, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Racial disparities in the association between alcohol use disorders and health in black and white women. Biodemography Soc Biol. 2017;63:236–52.

Inpatient stays involving mental and substance use disorders. 2016. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb249-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorder-Hospital-Stays-2016.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Facing addiction in America: the surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington: HHS; 2016.

Ray LA, Meredith LR, Kiluk BD, Walthers J, Carroll KM, Magill M. Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with alcohol or substance use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208279.

Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Carroll KM. We don’t train in vain: a dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:106–15.

Greist JH. A promising debut for computerized therapies. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:793–5.

Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Computer-assisted therapy in psychiatry: be brave—it’s a new world. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:426–32.

Postel MG, de Jong CA, de Haan HA. Does e-therapy for problem drinking reach hidden populations? Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2393.

Marks IM, Cavanagh K. Computer-aided psychological treatments: evolving issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:121.

McCaul ME, Svikis DS, Moore RD. Predictors of outpatient treatment retention: patient versus substance use characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:9–17.

Matsuzaka S, Knapp M. Anti-racism and substance use treatment: addiction does not discriminate, but do we? J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2020;19:567–93.

Kiluk BD, Devore KA, Buck MB, Nich C, Frankforter TL, LaPaglia DM, Yates BT, Gordon MA, Carroll KM. Randomized trial of computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for alcohol use disorders: efficacy as a virtual stand-alone and treatment add-on compared with standard outpatient treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:1991–2000.

Paris M, Silva M, Anez-Nava L, Jaramillo Y, Kiluk BD, Gordon MA, Nich C, Frankforter T, Devore K, Ball SA, Carroll KM. Culturally adapted, web-based cognitive behavioral therapy for Spanish-speaking individuals with substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1535–42.

King C, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Priest KC, Englander H. Patterns of substance use before and after hospitalization among patients seen by an inpatient addiction consult service: a latent transition analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;118:108121.

Jordan A, Quainoo S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, Funaro M, Carroll KM: An evaluation of racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol, cannabis, and illicit substance use treatment initiation, engagement, and treatment outcome: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials.

Hahn JA, Murnane PM, Vittinghoff E, Muyindike WR, Emenyonu NI, Fatch R, Chamie G, Haberer JE, Francis JM, Kapiga S, et al. Factors associated with phosphatidylethanol (PEth) sensitivity for detecting unhealthy alcohol use: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45:1166–87.

Johansson K, Johansson L, Pennlert J, Soderberg S, Jansson JH, Lind MM. Phosphatidylethanol levels, as a marker of alcohol consumption, are associated with risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020;51:2148–52.

Edelman EJ, Dziura J, Deng Y, Bold KW, Murphy SM, Porter E, Sigel KM, Yager JE, Ledgerwood DM, Bernstein SL. A SMART approach to treating tobacco use disorder in persons with HIV (SMARTTT): rationale and design for a hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;110:106379.

Drummond MS, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluatoin of health prorgrammers. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Pres; 2015.

Hornack SE, Yates BT. Costs, benefits, and net benefit of 13 inpatient substance use treatments for 14,947 women and men. Eval Program Plann. 2022;97:102198.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory care quality improvement project (ACQUIP). Alcohol use disorders identification test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–95.

Joudrey PJ, Oldfield BJ, Yonkers KA, O’Connor PG, Berland G, Edelman EJ. Inpatient adoption of medications for alcohol use disorder: a mixed-methods formative evaluation involving key stakeholders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108090.

Hallgren KA, Matson TE, Oliver M, Caldeiro RM, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Practical assessment of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria in routine care: high test-retest reliability of an alcohol symptom checklist. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2022;46:458–67.

Hallgren KA, Matson TE, Oliver M, Witkiewitz K, Bobb JF, Lee AK, Caldeiro RM, Kivlahan D, Bradley KA. Practical assessment of alcohol use disorder in routine primary care: performance of an alcohol symptom checklist. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:1885–93.

Donroe JH, Edelman EJ. Alcohol use. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:ITC145–60.

Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, DelBoca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;Supplement 12:70–5.

Wei LJ. An application of an urn model to the design of sequential controlled clinical trials. J Am Stat Assoc. 1978;73:559–63.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. Initiation and engagement of alcohol and other drug abuse or dependence treatment (IET).

Harris AH, Humphreys K, Bowe T, Tiet Q, Finney JW. Does meeting the HEDIS substance abuse treatment engagement criterion predict patient outcomes? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2010;37:25–39.

D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1636–44.

D’Onofrio G, Edelman EJ, Hawk KF, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Martel SH, Van Veldhuisen P, Oden N, Murphy SM, et al. Implementation facilitation to promote emergency department-initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder: protocol for a hybrid type III effectiveness-implementation study (Project ED HEALTH). Implement Sci. 2019;14:48.

EXHIT ENTRE Comparative Effectiveness Trial (EXHIT ENTRE), ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04345718. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04345718?term=bart+and+saitz&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Mee-Lee DE. The ASAM criteria: treatment criteria for addictive, substance-related, and co-occurring conditions. Rockville: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013.

What are the ASAM Levels of Care?. https://www.asamcontinuum.org/knowledgebase/what-are-the-asam-levels-of-care/. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Yates BT. Cost-inclusive research on health psychology interventions: why, how, and what next. Health Psychol. 2023;42:139–50.

O’Connor EA, Perdue LA, Senger CA, Rushkin M, Patnode CD, Bean SI, Jonas DE. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:1910–28.

Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:557–68.

Barry DT, Moore BA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Sullivan LE, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. Patient satisfaction with primary care office-based buprenorphine/naloxone treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:242–5.

D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Degutis LC, Busch SH, Bernstein SL, O’Connor PG. A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:181–92.

D’Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, Fiellin DA, Busch SH, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, O’Connor PG. Brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(742–750):e742.

D’Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Development and implementation of an emergency practitioner-performed brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:249–56.

D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Degutis LC, Busch SH, Bernstein SL, O’Connor PG. A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:181–92.

Connors GJ, DiClemente CC, Velasquez MM, Donovan DM. Substance abuse treatment and the stages of change: selecting and planning interventions. New York: Guilford Press; 2013.

Edelman EJ, Dinh A, Radulescu R, Lurie B, D’Onofrio G, Tetrault JM, Fiellin DA, Fiellin LE. Combining rapid HIV testing and a brief alcohol intervention in young unhealthy drinkers in the emergency department: a pilot study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:539–43.

Edelman EJ, Maisto SA, Hansen NB, Cutter CJ, Dziura J, Fiellin LE, O’Connor PG, Bedimo R, Gibert C, Marconi VC, et al. The starting treatment for ethanol in primary care trials (STEP Trials): protocol for three parallel multi-site stepped care effectiveness studies for unhealthy alcohol use in HIV-positive patients. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;52:80–90.

Joint Commission. Specifications manual for Joint Commission National Quality Core Measures (2010A1).

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration ed., HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907 edition. Rockville; 2015.

Medications for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. https://www.qmo.amedd.army.mil/substance%20abuse/22-001_05_AUD_medications_SUD_CST_508.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Kadden R, Carroll KM, Donovan D, Cooney JL, Monti P, Abrams D, Litt M, Hester RK. Cognitive-behavioral coping skills therapy manual: a clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Rockville: NIAAA; 1992.

Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio T, Gordon MA, Portnoy GA, Rounsaville BJ. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: a randomized clinical trial of ‘CBT4CBT.’ Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:881–8.

Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, Gordon MA, Portnoy G, Marino D, Ball SA. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy: efficacy and durability of CBT4CBT among cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:436–44.

Carroll KM, Nich C, DeVito EE, Shi JM, Sofuoglu M. Galantamine and computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for cocaine dependence: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;79:17m11669.

Kiluk BD, Nich C, Buck MB, Devore KA, Frankforter TL, LaPaglia DM, Muvvala SB, Carroll KM. Randomized clinical trial of computerized and clinician-delivered CBT in comparison with standard outpatient treatment for substance use disorders: primary within-treatment and follow-up outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:853–63.

Tetrault JM, Holt SR, Cavallo DA, O’Connor PG, Gordon MA, Corvino JK, Nich C, Carroll KM. Computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders in a specialized primary care practice: a randomized feasibility trial to address the RT component of SBIRT. J Addict Med. 2020;14:e303–9.

Shi JM, Henry SP, Dwy SL, Orazietti SA, Carroll KM. Randomized pilot trial of Web-based cognitive-behavioral therapy adapted for use in office-based buprenorphine maintenance. Subst Abus. 2019;40:132–5.

Foxcroft DR, Coombes L, Wood S, Allen D, Almeida Santimano NM. Motivational interviewing for alcohol misuse in young adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:CD007025.

Lee CS, Lopez SR, Colby SM, Rohsenow D, Hernandez L, Borrelli B, Caetano R. Culturally adapted motivational interviewing for Latino heavy drinkers: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2013;12:356–73.

Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: twenty-five years of empirical studies. Res Soc Work Pract. 2010;20:137–60.

VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37:768–80.

Rahm AK, Boggs JM, Martin C, Price DW, Beck A, Backer TE, Dearing JW. Facilitators and barriers to implementing screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in primary care in integrated health care settings. Subst Abus. 2015;36:281–8.

Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Feldman J, Fernandez W, Hagan M, Mitchell P, Safi C, Woolard R, Mello M, Baird J, et al. An evidence based alcohol screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) curriculum for emergency department (ED) providers improves skills and utilization. Subst Abus. 2007;28:79–92.

Nich C, Carroll KM. Now you see it, now you don’t: a practical demonstration of random regression versus traditional ANOVA models in the analysis of longitudinal follow-up data from a clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:252–61.

Nich C, Carroll KM. Intention to treat meets missing data: implications of alternate strategies for analyzing clinical trials data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:121–30.

Afshar M, Burnham EL, Joyce C, Clark BJ, Yong M, Gaydos J, Cooper RS, Smith GS, Kovacs EJ, Lowery EM. Cut-point levels of phosphatidylethanol to identify alcohol misuse in a mixed cohort including critically Ill patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:1745–53.

Eyawo OD. Validating self‐reported unhealthy alcohol use with phosphatidylethanol (PEth) among patients with HIV. ACER. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14435.

Burlew AK, Feaster D, Brecht ML, Hubbard R. Measurement and data analysis in research addressing health disparities in substance abuse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36:25–43.

Burlew AK, Weekes JC, Montgomery L, Feaster DJ, Robbins MS, Rosa CL, Ruglass LM, Venner KL, Wu LT. Conducting research with racial/ethnic minorities: methodological lessons from the NIDA clinical trials network. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:324–32.

Burlew AK. Alternative approaches to racial/ethnic research. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2019;18:1–2.

Sung ML, Viera A, Esserman D, Tong G, Davidson D, Aiudi S, Bailey GL, Buchanan AL, Buchelli M, Jenkins M, et al. Contingency management and pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence support services (CoMPASS): a hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation study to promote HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs. Contemp Clin Trials. 2022;125:107037.

Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e38-46.

Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:119–27.

Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. 2020;8:134.

Hasin DS, Aharonovich E, O’Leary A, Greenstein E, Pavlicova M, Arunajadai S, Waxman R, Wainberg M, Helzer J, Johnston B. Reducing heavy drinking in HIV primary care: a randomized trial of brief intervention, with and without technological enhancement. Addiction. 2013;108:1230–40.

Hamilton FL, Hornby J, Sheringham J, Linke S, Ashton C, Moore K, Stevenson F, Murray E. DIAMOND (DIgital Alcohol Management ON Demand): a mixed methods feasibility RCT and embedded process evaluation of a digital health intervention to reduce hazardous and harmful alcohol use. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017;3:34.

Vaca FE, Dziura J, Abujarad F, Pantalon M, Hsiao A, Reynolds J, Maciejewski KR, Field CA, D’Onofrio G. Use of an automated bilingual digital health tool to reduce unhealthy alcohol use among Latino emergency department patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2314848.

Eyawo O, Deng Y, Dziura J, Justice AC, McGinnis K, Tate JP, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Hansen NB, Maisto SA, Marconi VC, et al. Validating self-reported unhealthy alcohol use with phosphatidylethanol (PEth) among patients with HIV. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020;44(10):2053–63.

Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:482.

Edelman EJ, Cole CA, Richardson W, Boshnack N, Jenkins H, Rosenthal MS. Stigma, substance use and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: a qualitative study. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:296–302.

Cowan E, Khan MR, Shastry S, Edelman EJ. Conceptualizing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with opioid use disorder: an application of the social ecological model. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16:4.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9.

Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The self-administered comorbidity questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–63.

Medical Monitoring Project. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/systems/mmp/index.html. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Wilson IB, Tie Y, Padilla M, Rogers WH, Beer L. Performance of a short, self-report adherence scale in a probability sample of persons using HIV antiretroviral therapy in the United States. AIDS. 2020;34:2239–47.

Wilson IB, Lee Y, Michaud J, Fowler FJ Jr, Rogers WH. Validation of a new three-item self-report measure for medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2700–8.

Hanmer J, Dewitt B, Yu L, Tsevat J, Roberts M, Revicki D, Pilkonis PA, Hess R, Hays RD, Fischhoff B, et al. Cross-sectional validation of the PROMIS-Preference scoring system. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0201093.

Sobell LC, Sobell SM. Alcohol timeline followback (TLFB); handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1996.

Timko C, Moos RH, Finney JW, Connell EG. Gender differences in help-utilization and the 8-year course of alcohol abuse. Addiction. 2002;97:877–89.

Viel G, Boscolo-Berto R, Cecchetto G, Fais P, Nalesso A, Ferrara SD. Phosphatidylethanol in blood as a marker of chronic alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:14788–812.

Lieberman DZ, Cioletti A, Massey SH, Collantes RS, Moore BB. Treatment preferences among problem drinkers in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2014;47:231–40.

Stewart SH, Connors GJ. Interest in pharmacotherapy and primary care alcoholism treatment among medically hospitalized, alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis. 2007;26:63–9.

DiClemente CC, Carbonari JP, Montgomery RP, Hughes SO. The alcohol abstinence self-efficacy scale. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:141–8.

Kiluk BD, Dreifuss JA, Weiss RD, Morgenstern J, Carroll KM. The short inventory of problems-revised (SIP-R): psychometric properties within a large, diverse sample of substance use disorder treatment seekers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:307–14.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 2013.

Ali R, Meena S, Eastwood B, Richards I, Marsden J. Ultra-rapid screening for substance-use disorders: the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST-Lite). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:352–61.

Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: The accountable health communities screening tool. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Standardized-Screening-for-Health-Related-Social-Needsin-Clinical-Settings.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: from psychometrics to ecometrics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:858–67.

Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The group-based medical mistrust scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38:209–18.

Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–51.

Pew Hispanic Center: Pew Hispanic Center Poll: 2007 National Survey of Latinos. (International Communications R ed., 2nd ed. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research; 2007.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy: National Latino Health and Immigration survey 2015. 2015.

Rodriguez N, Flores T, Flores RT, Myers HF, Vriesema CC. Validation of the multidimensional acculturative stress inventory on adolescents of Mexican origin. Psychol Assess. 2015;27:1438–51.

Phinney JS, Ong AD. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: current status and future directions. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54:271–81.

Olmstead TA, Sindelar JL, Easton CJ, Carroll KM. The cost-effectiveness of four treatments for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01909.x.

Olmstead TA, Ostrow CD, Carroll KM. Cost-effectiveness of computer-assisted training in cognitive-behavioral therapy as an adjunct to standard care for addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:200–7.

Olmstead TA, Sindelar JL, Petry NM. Cost-effectiveness of prize-based incentives for stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:175–82.

Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1986;22:343–81.

Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry RL, et al. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;57(3):225–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6

Dnofrio G, Hawk KF, Herring AA, Perrone J, Cowan E, McCormack RP, Dziura J, Taylor RA, Coupet E, Edelman EJ, et al. The design and conduct of a randomized clinical trial comparing emergency department initiation of sublingual versus a day extended-release injection formulation of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder: project ED innovation. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;104:106359.

Miller WaR S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. New York: Guilford Press; 2013.

Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Levenson S. Project ASSERT: an ED-based intervention to increase access to primary care, preventive services, and the substance abuse treatment system. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:181–9.

Screening brief intervention & referral to treatment: implementation tools. https://medicine.yale.edu/sbirt/implementation/tools/. Accessed 3 Sep 2023.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Ms. Caitlin Partridge’s assistance with extraction of data to characterize the YNHH patient population.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AA029820. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EJE, CN, AJ, MBW, MP, BY, ECW, and BDK contributed to the original design of the study and obtaining grant funding. EJE and BK hold primary responsibility for the conduct of the study and provide oversight for all aspects of the study implementation. OFRP has been a major contributor in designing the intervention materials and assessment battery in collaboration with the team of investigators, particularly including AJ, MP, DG, ECW, EJE and BDK. BY holds primary responsibility for cost, cost-effectiveness, and cost–benefit analyses and reporting. All investigators help oversee implementation of the intervention. TF oversees and holds primary responsibility of data management. CN oversees and hold primary responsibility for conduct of analyses. JC oversees regulatory aspects of the protocol. EJE wrote the initial draft of this manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This HIPAA-compliant study is approved by the Yale School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee (protocol #2000031874). Written informed consent is obtained prior to study participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

BDK and CN are paid consultants to CBT4CBT, LLC, which makes some versions of CBT4CBT available to qualified clinical providers and organizations on a commercial basis. This conflict is managed by Yale University. MBW has stock options with Path CCM, a telehealth behavioral health treatment company. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Project ENHANCE Health Promotion Adovcate Intervention Manual.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Edelman, E.J., Rojas-Perez, O.F., Nich, C. et al. Promoting alcohol treatment engagement post-hospitalization with brief intervention, medications and CBT4CBT: protocol for a randomized clinical trial in a diverse patient population. Addict Sci Clin Pract 18, 55 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-023-00407-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-023-00407-9