Abstract

Background

Emerging data points to a potential heroin use epidemic in South Africa. Despite this, access to methadone maintenance therapy and other evidence-based treatment options remains negligible. We aimed to assess retention, changes in substance use and quality of life after 6 months on methadone maintenance therapy provided through a low-threshold service in Durban, South Africa.

Methods

We enrolled a cohort of 54 people with an opioid use disorder into the study. We reviewed and described baseline socio-demographic characteristics. Baseline and 6-month substance use was assessed using the World Health Organization’s Alcohol Smoking and Substance Use Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and quality of life, using the SF-12. We compared changes at 6 months on methadone to baseline using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and paired-tests for the ASSIST and SF-12 scores, respectively. McNemar’s test was used for comparisons between paired results of categorical variables relating to injecting frequency.

Results

The majority of the participants were young, Black African males, with a history of drug use spanning over 10 years. Retention after 6 months was 81%. After 6 months, the median heroin ASSIST score decreased from 37 to 9 (p < 0.0001) and the cannabis ASSIST score increased from 12.5 to 21 (p = 0.0003). The median mental health composite score of the SF-12 increased from 41.4 to 48.7 (p = 0.0254).

Conclusions

Interim findings suggest high retention, significant reductions in heroin use and improvements in mental health among participants retained on methadone maintenance therapy for 6 months. Further research into longer term outcomes and the reasons contributing to these changes would strengthen recommendations for the scale-up of methadone maintenance therapy in South Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Opioid use carries significant risks and the resolution of opioid use disorders is challenging [1, 2]. Opioids (including heroin) are responsible for four out of five drug related deaths globally [3]. Injecting drug use significantly increases the chances of developing infections and suffering a variety of health issues, including contracting HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) [4]. Stigma, social exclusion, a lack of accessible services (including healthcare) and criminalisation add to the challenges confronting opioid dependent people [5]. Dependent opioid users experience unpleasant and painful symptoms of physical withdrawal unless they take regular doses (three-six hourly) [6]. Some people who use opioids find temporary relief from the physical and emotional pain they may be experiencing [7,8,9,10]. Stopping opioids is often an unrealistic or undesirable outcome for many people who use them. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends opioid agonist treatment for the treatment of opioid use disorders due to its effectiveness [11].

Methadone and buprenorphine are opioid agonist medications that act on the same receptors in the brain as opioids and relieve symptoms of withdrawal [11]. Opioid agonist treatment involves a trained clinician prescribing agonist medications at appropriate doses. At appropriate doses, this therapy reduces opioid use [11, 12] and the risk of HIV and HCV infection among people who inject drugs, increases adherence to antiretroviral therapy [13] and reduces mortality by up to 75% [14]. Opioid agonist treatment dramatically reduces the medical and societal costs related to opioid use [15, 16]. For every dollar invested in opioid agonist treatment, $5–$12 are saved on potential costs related to opioid use disorders where agonist medications are not prescribed. Additional savings occur when crime and criminal justice costs are considered [13]. Methadone maintenance therapy refers to opioid agonist treatment that is limited to the use of methadone for maintenance.

Community based, low threshold approaches to methadone maintenance improve retention [17]. These enable easy access (including mechanisms to link people with opioid use disorders to treatment), operate with limited resources, and are accessible to participants with limited financial resources and in contexts where drug use is criminalised [17]. Retention is enhanced by offering patient-centred dosing (without ceiling doses), minimising barriers to entry, and adopting approaches that do not demand total abstinence from opioid or other drugs [17,18,19]. In contrast, high threshold approaches have strict entry requirements, are abstinence-centric, require frequent urinalysis, have rigid dosing, and mandate psychosocial support [17]. Low threshold programmes are therefore a more realistic option for many opioid users [20, 21].

Opioid use is increasing in South Africa with few institutions or mechanisms to prevent what could become a public health crisis [22]. Seizures of heroin in East Africa have risen 100 fold over the past decade, indicating a significant increase in trafficking. Much of the trafficked heroin is bound for South Africa [23]. There is, however, no reliable empirical data on the prevalence of heroin use in the country. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that 0.5% of the population aged 15–64 in South Africa has used opioids in the past year [24], translating to around 184,030 people [25]. Most heroin is smoked or inhaled, either alone or in combination with other substances (e.g. tobacco or cannabis) [26]. The cost of a gram of heroin in South Africa fell threefold from 2004 to 2014 [27]. To date, the country has relied almost exclusively on abstinence based residential treatment or out-patient services with very low ‘success’ rates, usually measured in terms of abstinence [28, 29].

The World Health Organization’s comprehensive package of HIV and viral hepatitis prevention, testing, treatment and care interventions have neither been funded nor implemented by the South African government [30, 31]. South Africa’s first needle and syringe programme started in 2014 in Cape Town, extending to Durban and Pretoria in 2015. In May 2018 the Durban municipality stopped the needle and syringe programme for their cited concerns of insufficient stakeholder consultation and management of used injecting equipment [32], which by January 2020 was still on hold.

Between January and June 2018, 4% of the 7316 people who inject opioids who accessed harm reduction programmes were started on opioid agonist treatmentFootnote 1 [33]. Methadone and buprenorphine (± naloxone) are registered for use and only methadone is listed on the essential medicine list for use at hospital level for detoxification (i.e. neither medication is available in the public sector for maintenance) [31, 34]. Agonist medications are prescribed by medical practitioners in the private sector, civil society organisations and universities. Between 2015–2017 South Africa’s consumption of narcotic drugs and buprenorphine was ranked 74th globally (521 defined daily doses per million inhabitants per day; 35 for methadone and 15 for buprenorphine) [35]. The first opioid agonist treatment clinic started in 2011 at Stikland Hospital (Cape Town), with patients self-funding their medications, with a similar clinic starting at Groote Schuur Hospital (Cape Town) 2 years later. The first community-based opioid agonist treatment programme was started in 2014 by a civil society organisation with local government funding. The project provided buprenorphine-naloxone for 3 months to non-injecting opioid users using a high threshold approach with 66% (44/67) completing the project [29]. The limited access to opioid agonist treatment has been partly due to concerns around limited acceptance of the intervention by key stakeholders [31], safety concerns [36], and the impact on the health system and prohibitive costs [28]. Naltrexone in tablet form is registered and only available for use in the private sector. Naloxone is listed on South Africa’s essential medicine list for the management of opioid poisoning across all levels of care [37]. To date, no naloxone distribution programmes have taken place [38].

In response to these issues, the alignment of low-threshold approaches with harm reduction principles [17] and our experience, as well as a donation of methadone, we implemented South Africa’s first low threshold methadone maintenance therapy project. At the time of project planning implementing the project within a government primary care health facility was not possible. Here we present participant baseline social, demographic and drug use data, as well as retention and changes in quality of life and substance use after 6 months on the study. Qualitative research findings around participant experiences will be presented in a separate paper.

Methods

The study is based on a cohort of 54 people dependent on heroin in Durban, South Africa. The sample size was based on financial and human resources that were available for the project, with a focus on people who smoke heroin (80% of the cohort), reflecting the modes of opioid use in the city [26]. The participants were to receive 18 months of prescribed methadone from a community based low-threshold programme that also provided a needle and syringe and broader harm reduction service in the inner city suburb of Umbilo. Enrolment began in April 2017, and was staggered over 6 months.

Inclusion criteria included: aged 18 years or older; ≥ 12 months history of heroin use with a World Health Organization Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) score of ≥ 27Footnote 2 [39]; confirmed recent use of opioids through urinalysis; no pending court case; ability to attend daily clinic visits; a person who could provide support outside the programme; had stable accommodation for the past 3 months; agreed to be contacted for follow-up, and provided informed consent. In an attempt to reduce the risk of overdose and minimise clinical risks for this project people were excluded if they met the diagnostic criteria for an acute alcohol or benzodiazepine use disorder; had a psychotic disorder; or had a history of severe head injury, or cardiac, respiratory or liver condition.

This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Durban University of Technology (REC 29/15) and the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health’s Research Ethics Committee (reference KZ_2016RP14_267). Participants provided written informed consent as part of screening processes. They were not remunerated for participation.

Stakeholder engagement

Prior to conducting the study, a multi-stakeholder task team was established to inform protocol development and to oversee implementation. This included representatives from the national and provincial Departments of Health and Social Development, police, academics, harm reduction practitioners and (potential) study participants. The task team met bi-annually to reflect on progress, develop opportunities for collaboration, identify referral networks and reflect on challenges and future endeavours.

Recruitment, pre-screening, screening and initiation

People were informed about methadone prescribing and the programme through organisations providing harm reduction and other health and social services for those who use drugs in the city, as well as through members of the community of people who use drugs. Members of the study team pre-screened potential participants to ensure that they complied with the inclusion criteria stated above.

As part of screening, a study team member collected baseline data on sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, race, living situation, criminal record) and substance use (using WHO ASSIST and questions around current and previous drug use patterns, including opioid agonists). The study nurse conducted a medical history, physical examination, urine analysis for opioids, and an electrocardiogram (ECG). ECGs were included to identify people with potential cardiac problems at baseline and to gather data on changes over time to generate local safety data. The timing of ECGs was done following the South African guidelines for the management of opioid dependence developed by the South African Addiction Medicine Society [40], which recommends baseline, one month and annual ECG assessment. People with abnormal ECGs were referred to the nearest public hospital for further assessment. A study team member also offered HIV counselling and testing. A multi-disciplinary study team (involving clinical staff, researchers and psychosocial service staff) assessed participants’ suitability and eligible participants were medically assessed by a doctor. Participants signed a treatment contract outlining the nature of the study and the expectations of the participant and staff. The doctor initiated participants onto methadone at an appropriate dose in accordance with the South African Addiction Medicines Society guidelines, which recommends a starting dose of between 10 and 30 mg [41]. The nurse then completed the SF-12 quality of life assessment. This generic preference-weighted health outcomes assessment includes 12 questions. The Quality Metric’s Health Outcomes scoring software enables the generation of quality of life scores [42]. The SF-12 questions around physical functioning, physical state, bodily pain and general health, are used to develop a physical health composite score. Questions about vitality, social functioning, emotional state and mental health are used to develop a mental health composite score. A SF-6D Health Utility Index score is also generated. This preference-based index is used to measure health status, ranging from worst health state (0.0) to perfect health (1.0). The SF-6D score can be used to calculate quality adjusted life years for economic evaluations. The SF-12 has been validated for use in the South African context [42].

Follow-up visits

Initially, all participants came to the centre for daily observed dosing and were seen by the project nurse and other staff. Participants saw the medical doctor for clinical assessments every 3 to 7 days for the first 2 months as doses were increased and then stabilised, with no ceiling. Participants who had been on a stable maintenance dose for around 3 months were considered for take home doses with monthly medical assessments. A multi-disciplinary team involving the medical doctor, nurse and psychosocial support team decided on the commencement of take home dosing. Take home doses were terminated and daily observed doses reinstated if the participant repeatedly diverted, sold or otherwise misused the methadone supplied. Participants returned to daily observed dosing if their lives had been significantly destabalised. The SF-12, ASSIST, and HIV testing were repeated after 6 months on methadone.

Psychosocial services

All participants were provided with optional psychosocial support services. Throughout the demonstration project, a social worker and counsellor were available for individual consultations and for group sessions. Following a harm reduction approach, beneficiaries were asked to define their goals and were encouraged to talk without fear of victimisation or judgement of their drug use (past and present). Abstinence was not a requirement for receiving methadone or participation in the study. Shortly after the programme began, beneficiaries started their own peer-led support group. The social worker and/or counsellor assisted in the initial meetings, but fairly quickly the peer-led groups operated independently of ‘professional intervention’. Participation in at least two group sessions and at least one individual session each month was considered regular attendance. A group for family members and other people supporting participants on methadone was established and met every 4 months.

Multi-disciplinary support

Weekly multi-disciplinary meetings of clinical, psychosocial, support and research staff were held to discuss participants. Clinical and psychosocial plans were developed as required.

Termination, loss to follow-up and re-entry

Participants who voluntarily terminated their participation were counselled and supported through a down titration process. These participants were viewed as having exited the programme. The protocol allowed for involuntary termination if participants were repeatedly found to divert or traffic methadone. Participants were considered lost to follow-up if they missed 30 consecutive doses. Participants were able and encouraged to restart methadone at any stage if they were deemed lost to follow-up and were interested in re-entry, following a medical and psychosocial assessment.

Data management

Clinical notes and ASSISTs were completed on paper and captured into a password protected excel database. The SF-12 s were captured into Quality Metric’s Optum PRO CoRE Health Outcomes software (Eden Prairie, Minnesota) and exported into a password protected excel document. Data was merged and imported into Stata v14.2 (College Station, Texas) for analysis.

Quantitative data analysis

Descriptions of baseline data included proportions for categorical variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion (medians and inter-quartile ranges) for numerical variables. Substance specific and overall substance use scores were obtained from the ASSIST. Mental composite, physical composite and SF-6D scores were outputs from the Optum PRO CoRE Health Outcomes software. Paired t-tests (for normally distributed data) and the Wilcoxon signed rank test (for non-normally distributed data) were used to assess changes in substance use (ASSIST) and quality of life (SF-12 composite scores). McNemar’s test was used to calculate p values for paired data derived around injecting frequency in the preceding 3 months among participants completing baseline and 6-month ASSISTs. Retention in the study was used as a proxy measure for a positive outcome [43, 44].

Results

Demographic and social characteristics

Recruitment started in August 2017, and of the 110 people pre-screened 61% (67/110) were potentially eligible. Of these, 81% (54/67) signed treatment contracts and were enrolled. We initiated a total of 53 (48% of those pre-screened) people onto methadone (see Fig. 1). All participants who were contacted agreed to be pre-screened.

An overview of sociodemographic and substance use characteristics at baseline is provided in Table 1. The majority of the beneficiaries were young, black African males. Approximately half reported a criminal record and had used drugs for more than 10 years, respectively.

Baseline drug use practices

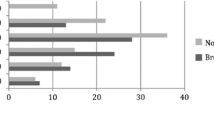

At baseline, nine participants reported injecting heroin within the previous 3 months while the remainder smoked heroin, usually in combination with tobacco and/ or cannabis. The majority (57%) used heroin more than four times per day. The median baseline ASSIST score for all substances was 81.5 (IQR 67–93), for opioids it was 37 (IQR 33–39) and cannabis 12.5 (IQR 3–23) (see Table 2). Cannabis (32%) was the second most common substance used.

Previous use of opioid agonist medications

In the month preceding initiation, seven (13%) of the participants reported using methadone, with two of them reporting that they stopped due to cost. Among them the median dose was 20 mg (IQR 10–50 mg) and reported dosing frequency ranged from once (n = 4) to thrice daily (n = 1). Additionally, six (11%) people reported using buprenorphine during the month before initiation with a median dose of 6 mg (IQR 4–8 mg) with daily (n = 3) or twice daily (n = 3) dosing.

Baseline quality of life

The baseline quality of life physical composite score was 55.5 (IQR 47.5–59.3), mental composite score 41.4 (IQR 35–47.3) and SF-6d-R2 0.657 (IQR 0.630–0.738) (see Table 3). The HIV prevalence at baseline was 13% (7/54). No abnormalities were seen on baseline ECGs done on eligible participants.

Results at 6 months

Retention, methadone dosing and psychosocial service uptake

Of the 110 applicants, 53 were initiated on methadone (one client signed consent but did not start methadone), with the median dose of methadone being 30 mg (IQR 30 mg). After 6 months, 81% (44/54) remained in the study. Seven people dropped out and could not be traced and two voluntarily exited. Of the nine people who started methadone and were not retained, 78% (7/9) left within 3 months of initiation. The median methadone dose among participants retained after 6 months was 55 mg (IQR 40–70 mg). The median methadone dose among participants lost to follow-up was 50 mg (IQR 30–60 mg). At the end of the 6-month period, 57% (25/44) were on daily observed therapy at the centre, while the rest received take-home doses. The median number of missed doses among participants remaining on OST after 6 months was 10 (IQR 3–21).

Voluntary group and individual psychosocial services were offered and 74% (40/54) of the participants regularly attended group sessions, 78% (42/54) participated in one or more individual sessions per month with the social worker or counsellor, and 74% (40/54) participated in group and individual sessions.

Quality of life and health

There was a statistically significant increase in the mental composite score after 6 months (p = 0.0254) among participants retained who completed an SF-12. Changes in the physical composite and SF-6d-R2 scores at 6 months (Table 3) were not significant. No new HIV infections were recorded among beneficiaries retained in the programme at the 6-month time point.

Drug use

Changes in ASSIST scores between baseline and at 6 months are shown in Table 2. Among those retained, there was a notable reduction in overall substance use. Overall, ASSIST scores decreased from a median of 81.5 to 67 (p = 0.0052). Opioid ASSIST scores reduced significantly from 37 to 9 (p < 0.0001), while cannabis increased significantly from 12.5 to 21 (p = 0.0003). There were insignificant increases in reported use of cocaine, and alcohol at 6 months. Among the 13 people who did not complete the 6 month ASSIST, 9 reported to have never injected at baseline.

Safety and adverse events

One patient, without a history of injecting drugs, who was living with HIV was lost to follow-up and died as a result of TB infection. One client had an opioid related overdose requiring supportive treatment. Two participants had mild increases in their QTC interval measurements after one month, both of which normalised after dose reduction and counselling.

Discussion

There are three key findings when comparing 6-month data with baseline from South Africa’s first low-threshold methadone maintenance therapy demonstration project. First, the retention was high (81%). Second, there were significant changes in substance use, specifically a reduction in opioid use and an increase in cannabis use. Third, improved mental health status was identified among retained participants. While the cohort is small and caution should thus be exercised in generalising from this study, these findings are indicative of the value of methadone maintenance therapy in a localised South African setting. Participants’ unanimous acceptance of procedures before initiating methadone points towards the acceptability of the implemented approach. The study is important as it demonstrates the strong positive outcomes of an observed and structured methadone maintenance therapy programme in an upper-middle income country context. Thirteen percent of the beneficiaries had previously accessed and used methadone, but in a non-structured, non-observed manner. The time taken to engage with stakeholders and develop protocols based on local and international recommended practice provided the setting for the study to successfully take place.

Retention

Retention is considered the best proxy indicator for positive outcomes in the resolution of opioid use disorders [43]. Internationally, retention rates for methadone maintenance therapy differ widely. At 6 months, rates of between 3 and 88% have been identified in the literature [45]. It has been suggested that the benchmark for methadone maintenance therapy is 50% [46]. However, a 2014 review of medication for opioid use disorder treatment programmes in lower and middle income countries reports average retention in methadone programmes as 72% (range 64–80%) at 6 months and 56% (range 46–68%) at 12 months [47].

The results from our study show 6-month retention rates that are at or above retention rates found in similar settings. However, the results are not totally unexpected. The programme was designed to include a number of factors that are predictive of high retention rates such as stable accommodation and a support person. Studies have repeatedly shown that individual characteristics are not predictive of outcomes, and that contextual factors including programmatic and social factors are predictive of positive outcomes. Programmatic predictors of high retention rates include individualised flexible dosing with no ceiling dose [48], accessibility (including cost and geographical position) [49] and therapeutic relationships [50]. Social factors include peer and family support [51]. The potential of take home doses also increases positive social factors [52]. These factors were included in the study design. Most of these features are common to low threshold programmes, which show higher levels of retention than higher threshold services [17,18,19].

One of the most consistent predictors of retention is methadone dose [53,54,55]. The globally recommended daily dose range for methadone is 60–120 mg [11]. Interestingly, the median methadone dose among participants retained at 6 months in this study was 55 mg. This could suggest that most beneficiaries did not require very high doses of methadone, most likely because the majority were not injectors [56]. The impact of lower doses was, we believe, mediated by the notable proportion of people on flexible and patient centred dosing (home dosing). Other potential factors include the option for re-initiation after being lost to follow-up and the employment of a non-punitive approach to service delivery.

Changes in quality of life

Positive change in mental health was significant at the 6-month mark. We infer that this is the result of connections with significant others, including the multi-disciplinary project team, peers and family members. These kinds of connections have been found to reduce feelings of stigmatisation and marginalisation and allow for life normalisation [57, 58]. While the analysis did not indicate any notable change in overall physical health, it is useful to bear in mind that there was low HIV prevalence at baseline, which did not change after 6 months.

Heroin and other drug use

The notable drop in the overall ASSIST score across all substance classes was to be expected and is supported by decades of research on the effectiveness of methadone [16, 43, 44, 48, 53, 59,60,61,62,63,64]. There was a significant increase in the use of cannabis amongst participants, however the reasons for this increase was not investigated. While some studies suggest that cannabis use is a predictor of lower retention rates [65, 66], a 2009 review concludes that it is not associated with worse opioid use outcomes. The review notes that there is no need to address cannabis use during methadone maintenance therapy unless the service user requests assistance [67]. A recent longitudinal study confirmed that daily cannabis use was related to better treatment outcomes [68]. Cannabis is a significantly less harmful substance than heroin [2, 69], is cheaper and because of a recent South African Constitutional Court ruling, the use of cannabis in a private space is now legal [70]. The reported levels of alcohol use was lower than expected, considering that alcohol is the most commonly reported substance of use among patients accessing substance use treatment services in the province [71]. An explanation for this could have been under-reporting of alcohol use.

Limitations

It was difficult to recruit women into the programme, perhaps because of the stigma attached to drug use [72]. Gender aside, the demographics in the cohort were fairly representative of the general population of the city in which the study took place.

The small sample size and opportunistic nature of recruitment limit the generalisability of the findings, although our findings align with global experience. The exclusion of people with unstable housing conditions, significant poly-substance use or people with major medical or psychiatric comorbidities, is likely to have contributed to the high retention rate. Two studies from other South African cities on opioid use treatment services have found a high prevalence (up to 49%) of psychiatric co-morbidity among patients accessing in-patient care in the public sector [73, 74].

Another limitation relates to data. Not all participants completed 6-month ASSISTS or SF-12 s and their inclusion in the analysis may have shifted some of findings, particularly in relation to the (increased) use of drugs, especially heroin, and mental health (worsening or no improvement). After initiation, substance use assessment was based on self-report, which could have led to an under estimate of concurrent use. However, supportive responses were used when participants reported drug use.

Our study did not assess details around participants’ prior access and experience of agonist medications or treatment of their opioid use disorder. As a result, we are unable to assess prior access to evidence-based treatment, and the extent to which opioid agonists were accessed illicitly.

Future research

This paper focuses on baseline and 6-month data. Data at the 12 month and 18 month intervals are also need to be collated and analysed, particularly in relation to the main findings, i.e. retention, drug use, and mental health. Qualitative research is needed to make sense of the facilitators and barriers to retention, as well as the participants’ health and drug use. It is also important that an analysis be conducted of the outcomes of low threshold opioid agonist treatment using buprenorphine and a cost effectiveness comparison in localised South African settings to inform policy and programming.

Conclusions

The harm reduction and low-threshold approach used in this project was significant in retaining participants up until the 6-month mark. While a range of other contributing factors should be further explored, our interim findings suggest that this model of methadone maintenance therapy in the South African context is likely to be acceptable to people and has the potential to achieve high retention rates.

The decline in the use of heroin and increased use of cannabis is significant. If harm reduction was a primary goal of this project, it was achieved. At the 6-month mark, this demonstration project resulted in participants reducing potential drug related harms. Combined with the improvement in mental health, this provides good reason for increased access to methadone maintenance therapy to those with an opioid use disorder who wish to normalise their lives. It makes sense, then, for government to investigate the provision of methadone maintenance therapy at the primary health care level in the public sector. A low threshold approach, particularly with regard to the use of flexible dosing (including take home dosing) and non-compulsory psycho-social service uptake, would significantly reduce the cost of such a roll-out.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Between January and June 2018, 260 people who inject drugs were on OST across five major cities through non-government and not-for-profit services.

ASSIST provides a score (overall and disaggregated by substance) reflecting the level of risk (low, moderate and high).

Abbreviations

- ASSIST:

-

Alcohol smoking and substance involvement screening test

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- UNODC:

-

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Lopez-Quintero C, Roth KB, Eaton WW, Wu L, Cottler LB, Bruce M, et al. Mortality among heroin users and users of other internationally regulated drugs: a 27-year follow-up of users in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program household samples. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:104–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.030.

van Amsterdam J, Nutt D, Phillips L, van den Brink W. European rating of drug harms. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:655–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881115581980.

UNODC. World Drug Report Executive summary. Conclusions and Policy Implications. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2018.

Larney S, Peacock A, Leung J, Colledge S, Hickman M, Vickerman P, et al. Global, regional, and country-level coverage of interventions to prevent and manage HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Heal. 2017;5:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30373-X.

UNAIDS. Health, rights and drugs. Harm reduction, decriminalization and zero discrimination for people who use drugs. 2019.

Stahl S. Stahl’s essential pscyhopharmacology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Somer E, Avni R. Dissociative phenomena among recovering heroin users and their relationship to duration of abstinence. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2003;3:25–38. https://doi.org/10.1300/J160v03n01_03.

Valentine K, Fraser S. Trauma damage and pleasure: Rethinking problematic drug use. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:410–6.

Schindler A, Thomasius R, Petersen K, Sack P-M. Heroin as an attachment substitute? Differences in attachment representations between opioid, ecstasy and cannabis abusers. Attach Hum Dev. 2009;11:307–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730902815009.

Kaiko RF, Wallenstein SL, Rogers AG, Grabinski PY, Houde RW. Analgesic and mood effects of heroin and morphine in cancer patients with postoperative pain. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1501–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198106183042501.

WHO. Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Beg M, Strathdee SA, Kazatchkine M. State of the Art Science addressing Injecting Drug Use, HIV and Harm Reduction. Int J Drug Policy. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.008.

World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS prevention. Position paper. 2004; 1–33.

Caplehorn JR, Dalton MS, Haldar F, Petrenas AM, Nisbet JG. Methadone maintenance and addicts’ risk of fatal heroin overdose. Subst Use Misuse. 1996;31:177–96.

Wilson DP, Donald B, Shattock AJ, Wilson D, Fraser-Hurt N. The cost-effectiveness of harm reduction. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:S5–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.007.

Connock M, Juarez-Garcia A, Jowett S, Frew E, Liu Z, Taylor RJ, et al. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:1–171.

Kourounis G, Richards BDW, Kyprianou E, Symeonidou E, Malliori M-M, Samartzis L. Opioid substitution therapy: lowering the treatment thresholds. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.021.

Christie TKS, Murugesan A, Manzer D, Shaughnessey MVO, Webster D. Evaluation of a low-threshold / high-tolerance methadone maintenance treatment clinic in saint john, new Brunswick, Canada: 1 year retention rate and illicit drug use. J Addict. 2013;13:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/753409.

Torrens M, Castillo C, Pérez-Solá V. Retention in a low-threshold methadone maintenance program. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;41:55–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-8716(96)01230-6.

Harris J, McElrath K. Methadone as Social Control. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:810–24.

Gourlay J, Ricciardelli L, Ridge D. Users’ experiences of heroin and methadone treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1875–82.

Scheibe A, Marks M, Shelly S, Gerardy T, Domingo A, Hugo J. Developing an advocacy agenda for increasing access to opioid substitution therapy as part of comprehensive services for people who use drugs in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2018;108:800–2.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2015. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2015.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. UNODC 2018 Prevalence of drug use in the general population–national data. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2018.

Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2018. Statistical release P0302. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2018.

Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, Parry C, Bhana A, Kitshoff D, et al. Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends in South Africa. Res Brief. 2017;20:1–9.

Howell S, Harker-Burnhams N, Townsend L, Shaw M. The wrong type of decline: fluctuations in price and value of illegal substances in Cape Town. SA Crime Q. 2015;54(1):43–544.

Weich L. Defeating the dragon–can we afford not to treat patients with heroin dependence? S Afr J Psychiatry. 2010;16:75–9.

Michie G, Hoosain S, Macharia M, Weich L. Report on the first government-funded opioid substitution programme for heroin users in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2017;107:539–42.

World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Scheibe A, Shelly S, Versfeld A, Howell S, Marks M. Safe treatment and treatment of safety: call for a harm-reduction approach to drug-use disorders in South Africa. S Afr Health Rev. 2017;20:197–204.

van Dyk J. Durban cuts city’s only needle exchange programme. Bhekisisa. 2018. https://bhekisisa.org/article/2018-05-30-00-durban-cuts-citys-only-needle-exchange-programme/. Accessed 30 Nov 2019.

Scheibe A, Matima R, Schneider A, Basson R, Ngcebetsha S, Padayachee K, et al. Still left behind: harm reduction coverage and HIV treatment cascades for people who inject drugs in South Africa. In: 10th IAS Conference on HIV Science. Mexico; 2019.

South African National Department of Health. Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list for South Africa. Hospital level. 3rd ed. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2012.

International Narcotics Control Board. Narcotic drugs 2018. Estimated requirements for 2019. Statistics for 2017. 2018; 1–494. https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Technical-Publications/2018/INCB-Narcotics_Drugs_Technical_Publication_2018.pdf.

Weich L. Defeating the dragon—can we afford not to treat patients with heroin dependence? S Afr J Psychiatry. 2010. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v16i3.260.

National Department of Health. Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list for South Africa: primary healthcare level. 2018th ed. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health; 2018.

Harm Reduction International. The Global state of harm reduction 2018. 6th ed. London: Harm Reduction International; 2018.

World Health Organization. The alcohol smoking and substance involvement screening test. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Weich L, Nowbath H, Flegar S, Mahomedy Z, Ramjee H, Hitzeroth V, et al. South African guidelines for the management of opioid dependence. Updated 2013. 2013.

Weich L, Perkel C, van Zyl N, Rataemane P, Naidoo L, Nowbath H, et al. South African guidelines for the management of opioid dependence. S Afr Addict Med Soc. 2013;100:1–18.

Quality Metric Incorporated. User’s manual for the SF-12v2 Health survey. 3rd ed. Quality Metric Incorporated: Lincoln; 2012.

Veilleux JC, Colvin PJ, Anderson J, York C, Heinz AJ. A review of opioid dependence treatment: pharmacological and psychosocial interventions to treat opioid addiction. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:155–66.

Bell J. Pharmacological maintenance treatments of opiate addiction. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:253–63.

Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: a systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2016;35:22–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2016.1100960.

Ward J, Hall W, Mattick RP. Role of maintenance treatment in opioid dependence. Lancet. 1999;353:221–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05356-2.

Feelemyer J, Des Jarlais D, Arasteh K, Abdul-Quader AS, Hagan H. Retention of participants in medication-assisted programs in low- and middle-income countries: an international systematic review. Addiction. 2014;109:20–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12303.

Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:63–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000075.

Akindipe T, Abiodun L, Adebajo S, Lawal R, Rataemane S. From addiction to infection: managing drug abuse in the context of HIV/AIDS in Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18(3):47–544.

Brorson HH, Ajo Arnevik E, Rand-Hendriksen K, Duckert F. Drop-out from addiction treatment: a systematic review of risk factors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1010–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.007.

Yang F, Lin P, Li Y, He Q, Long Q, Fu X, et al. Predictors of retention in community-based methadone maintenance treatment program in Pearl River Delta. China Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-10-3.

Walley AY, Cheng DM, Pierce CE, Chen C, Filippell T, Samet JH, et al. Methadone dose, take home status, and hospital admission among methadone maintenance patients. J Addict Med. 2012;6:186–90.

Garcia-Portilla MP, Bobes-Bascaran MT, Bascaran MT, Saiz PA, Bobes J. Long term outcomes of pharmacological treatments for opioid dependence: does methadone still lead the pack? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:272–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12031.

Villafranca SW, McKellar JD, Trafton JA, Humphreys K. Predictors of retention in methadone programs: a signal detection analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:218–24.

Lo A, Kerr T, Hayashi K, Milloy MJ, Nosova E, Liu Y, et al. Factors associated with methadone maintenance therapy discontinuation among people who inject drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;94:41–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.08.009.

Smolka M, Schmidt LG. The influence of heroin dose and route of administration on the severity of the opiate withdrawal syndrome. Addiction. 1999;94:1191–8.

Shen L, Assanangkornchai S, Liu W, Cai L, Li F, Tang S, et al. Influence of social network on drug use among clients of methadone maintenance treatment centers in Kunming China. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0200105. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200105.

Kwan TH, Wong NS, Lee SS. Participation dynamics of a cohort of drug users in a low-threshold methadone treatment programme. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-015-0072-z.

Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M, Vecchi S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004147.pub4.

Amato L, Davoli M, Minozzi S, Ferroni E, Ali R, Ferri M. Methadone at tapered doses for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD003409.

Lingford-Hughes AR, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt DJ, et al. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:899–952.

Van Den Brink WW, Haasen C. Evidenced-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. Can J Psychiatry-Revue Can Psychiatr. 2006;51:635–46.

Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A Meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–87. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851.

Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M, Richard PM, Breen C, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD002207.

DA W, MG W, BE H, SM H. Factors associated with lapses to heroin use during methadone maintenance. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;52:183–92. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed4&NEWS=N&AN=1998393995.

Franklyn AM, Eibl JK, Gauthier GJ, Pellegrini D, Lightfoot NE, Marsh DC. The impact of cocaine use in patients enrolled in opioid agonist therapy in Ontario, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;48:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.044.

Epstein DH, Preston KL. Does cannabis use predict poor outcome for heroin-dependent patients on maintenance treatment? Past findings and more evidence against. [comment] [erratum appears in Addiction. 2003 Apr 98(4):538]. Addiction. 2003;98:269–79.

Socías ME, Wood E, Lake S, Nolan S, Fairbairn N, Hayashi K, et al. High-intensity cannabis use is associated with retention in opioid agonist treatment: a longitudinal analysis. Addiction. 2018;113:2250–8.

Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1558–65.

The Constitutional Court of South Africa. Minister of justice and constitutional development and others v prince (Clarke, Stobbs and Thorpe Intervening) (Doctors of Life International Inc as Amicus Curiae); National Director of Public Prosecutions and Others v Rubin; National Director of Public P. 2018. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12144/34547.

Dada S, Harker N, Jodilee B, Warren E, Parry C, Bhana A, et al. April 2019 Phase 44. Cape Town: SA Medical Research Council; 2019.

UNODC, UNWOMEN, WHO, INPUD. Women who inject drugs and HIV: addressing specific needs issue summary: the key reasons and unique challenges. Policy brief. 2014.

Dannatt L, Cloete KJ, Kidd M, Weich L. Frequency and correlates of comorbid psychiatric illness in patients with heroin use disorder admitted to Stikland Opioid Detoxification Unit, South Africa. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2014;20:77.

Morgan N, Daniels W, Subramaney U. A prospective observational study of heroin users in Johannesburg, South Africa: assessing psychiatric comorbidities and treatment outcomes. Compr Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152137.

Acknowledgements

Completion of this study would not have been possible without the participation and assistance of many people, particularly the study participants as well as inputs from the task team involved in project oversight. These include Dr. Nikiwe Hongo, Zane Dangor, Chris Overall, Nomusa Shembe, Raymond Perrier, Malusi Mbethe, and Dr. Stephen Carpenter.

Additional inputs into planning, training, service delivery and research processes were provided by Sibonelo Gumede, David Jones, Dr. Tamlynn Fleetwood, Dr. Katherine Young, Dr. Terence Moodley, Dr. Laurene Booyens, Jennifer Govender, and Dr. Anna Versfeld. Support from Machteld Busz, Muna Handulle and Hatun Eksen enabled successful study implementation.

Funding

Funding to conduct various elements of this research was received from the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, Open Society Foundation, Mainline through the Bridging the Gaps project. Implementation was contingent on support from the Global Fund, via Right to Care as it covered some of the costs relating to overheads and harm reduction services. Methadone for this study was donated by Equity Pharmaceuticals, who also supported training of medical and support staff but were not involved in protocol design or implementation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS (1) led the protocol development and was the lead team person involved in oversight of implementation, quantitative data analysis, development of drafts and incorporation of co-author inputs and finalisation of the manuscript. SS co-developed the protocol, and was also involved in oversight of implementation, data analysis, and the development of drafts and finalisation of the manuscript. TG was involved in oversight of implementation, input into drafts and review and approval of the final manuscript. ZH was responsible for data entry and cleaning, input into drafts and review and approval of the final manuscript. AS (2), KP, SN, KM, and AM were involved in oversight of implementation, input into drafts and review and approval of the final manuscript. HH contributed to the design of the work; interpretation of data; input into drafts and review and approval of the final manuscript. MM co-developed the protocol, and was involved in oversight of implementation, data analysis, and the development of drafts and finalisation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Durban University of Technology (reference: Invisible Lives: Pathways into and out of street level drug use in Durban) and the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health’s Research Ethics Committee (reference KZ_2016RP14_267). Participants provided written informed consent and were not remunerated for participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Equity Pharmaceuticals did not have input in the planning or implementation of the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Scheibe, A., Shelly, S., Gerardy, T. et al. Six-month retention and changes in quality of life and substance use from a low-threshold methadone maintenance therapy programme in Durban, South Africa. Addict Sci Clin Pract 15, 13 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-020-00186-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-020-00186-7