Abstract

Background

Systems science approaches have demonstrated effectiveness in identifying underlying drivers of complex problems and facilitating the emergence of potential interventions that are locally tailored, feasible, sustainable and evidence informed. Despite the potential usefulness of system dynamics simulation modelling and other systems science modelling techniques in guiding implementation, time and cost constraints have limited its ability to provide strong guidance on how to implement complex interventions in communities. Guidance is required to ensure systems interventions lead to impactful systems solutions, implemented utilising strategies from the intersecting fields of systems science and implementation science. To provide cost-effective guidance on how and where to implement in systems, we offer a translation of the ‘Meadows 12 places to act in a system’ (Meadows 12) into language useful for public health.

Methods

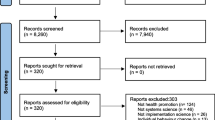

This translation of Meadows 12 was informed by our experience in working with 31 communities across two complex large scale randomised control trials and one large whole of community case study. These research projects utilised systems science and implementation science to co-create childhood obesity prevention interventions. The team undertaking this translation comprised research academics, implementation specialists and practitioners, practice-based researchers and a systems dynamicist. Our translation of each of the Meadows 12 levels to act in the system maintains the fidelity and nuance of the 12 distinct levels. We provide examples of each level of the Public Health 12 framework (PH12) drawn from 31 communities. All research was conducted in Victoria, Australia between 2016 and 2020.

Results

PH12 provides a framework to guide both research and practice in real world contexts to implement targeted system level interventions. PH12 can be used with existing implementation science theory to identify relevant strategies for implementation of these interventions to impact the system at each of the leverage points.

Conclusion

To date little guidance for public health practitioners and researchers exists regarding how to implement systems change in community-led public health interventions. PH12 enables operationalisation Meadows 12 systems theory into public health interventions. PH12 can help research and practice determine where leverage can be applied in the system to optimise public health systems level interventions and identify gaps in existing efforts.

Trial registration

WHO STOPS: ANZCTR: 12616000980437. RESPOND: ANZCTR: 12618001986268p.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Contributions to the literature

-

Several studies are now published that use systems methodologies to understand complex problems. Very few of these studies identify how and where to act in a system and those that do apply reduced versions of Meadows’s original 12 places to intervene in a system, thereby losing opportunity for maximum system impact.

-

The Public Health 12 Framework presented here provides specific guidance on how to use Meadows’s ground-breaking framework in public health interventions whilst maintaining fidelity to the original systems science constructs.

Background

Systems science has been applied to varied complex problems including physics and climate change [1], and more recently to address complex problems in public health such as obesity [2]. Advantages include providing a method to simultaneously consider and navigate the social ecological model of health [3]. Part of the power of using systems science to tackle complex health problems is that subsequent interventions are designed to be adaptive and provide space for multiple solutions to emerge [4].

Community-based system dynamics (CBSD) [5], and embedded techniques like group model building (GMB), are participatory, capture mental models of problems and model impacts of intervention effectiveness [5,6,7,8]. CBSD aligns with and builds on community-based prevention efforts which emphasise community capacity building [9,10,11], engagement and knowledge sharing [5]. In GMB, groups work with a facilitator to build a shared mental model of the causes of a problem from a local perspective [12]. From this shared model, participants can then identify places to act, relevant interventions and related implementation strategies adapted to the local context [13, 14]. Evidence of the effectiveness of GMB to build a common understanding of complexity and identify interventions is growing [8, 15].

Our understanding of which interventions or combination of actions are most influential to impact systems change is less advanced. Donella Meadows was a pioneer in system dynamics and engineering and proposed 12 places to intervene in a system for maximum impact [16], referred to as Meadows 12 (M12) (see Table 1). The original development of the M12 is described elsewhere, [16] but in brief, they were brainstormed in response to perceived flaws in the World Trade Organisation and other trade deals; and Meadows’ own experiences with systems thinking in general and system dynamics modelling in particular. The ideas were further refined prior to publication, but in the conclusion of the article, they are described as tentative, creating an invitation for further development [16]. System dynamics simulation modelling has been used as an implementation science tool in healthcare and health promotion [17], demonstrating its usefulness in adopting a systems approach to implementation science. However, given the cost and time required for simulation, there is a need to fast-track insights generated from simulation into community-based implementation. M12 is frequently referenced as a tool to translate these insights from system dynamics modelling. To date these insights are underutilised because of the difficulty in translating systems language to public health language, as demonstrated by multiple attempts to simplify the framework for use in public health [18, 19].

The leverage points are presented in order of their potential to create an impact from small changes to existing structures to the power to transcend paradigms. The M12 has been critiqued for its technical language and subsequent difficulty in translating to fields outside engineering [19, 20]. While others have adapted the M12 [18,19,20], their approach has been to collapse it into fewer levels, losing some of the nuance and fidelity to the original framework. We set out to translate M12 into language that maintains the structure of the original M12 and is specifically tailored for use by public health practitioners and researchers working on public health interventions, such as obesity prevention.

Aims

-

1.

To translate the M12 system intervention points into language useful for public health whilst maintaining fidelity to the 12 levels.

-

2.

To provide examples of the intervention points from three large-scale participatory community-based obesity prevention interventions conducted in Victoria, Australia 2016-2020.

Methods

Context

Building on previously reported community-based approaches to obesity prevention [9, 11], the Global Obesity Centre (GLOBE) at Deakin University has been trialling CBSD to empower communities for childhood obesity prevention since 2014 [21]. Two recent trials include the Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for Childhood Obesity (WHO STOPS) [22] and Reflexive Evidence and Systems interventions to Prevent Obesity and Non-communicable Disease (RESPOND) [23]. These are stepped wedge randomised control trials implemented over 4 years in regional Victoria, Australia; with five intervention communities implementing the intervention in year 1, and the other five communities in year 2. Communities in WHO STOPS (potential population reach 125,000) and RESPOND (potential population reach 213,600) were geographically bounded by local government areas, with the option of refinement of boundaries (i.e., by splitting a geographical area into two or more communities) based on community feedback. The outcomes of WHO STOPS are reported elsewhere [22] and the RESPOND trial is underway [23]. The third study, Yarriambiack – Creating Healthy, Active, Nourished Generations (YCHANGe), potential population reach 7026) was a whole of community obesity prevention initiative implemented in rural Victoria, Australia. The initiative was community-led with researcher oversight for 5 years, with some initiatives sustained long-term [24].

Each study used GMB informed by the scientific evidence base [12, 15] to build a causal loop diagram (CLD) that modelled a shared understanding of the issue. From this, multiple places to intervene in the system were identified along with relevant strategies, consensus and commitment to action [6, 15]. This co-creation of interventions and strategies represented a step beyond standard practice of implementing and testing a pre-defined program of activities and deliberately built community capacity in systems approaches to prevention.

Translating Meadows 12 definitions into public health language

Six members of the core research team (consisting of academic professors, implementation specialists, practice-based researchers, implementation practitioners and a systems dynamicist) initially reviewed the literature and compared the application and evaluation of existing public health system dynamics frameworks [25, 26]. We purposefully included expertise from both system dynamics and public health to maintain fidelity to both disciplines. PF previously held a community development role for 6 years and has spent the last 5 years as an implementation specialist building community capacity; ADB is a system dynamacist with 8 years in community-based prevention work and simulation modelling; JW has worked for > 20 years in health promotion prior to spending the last 10 years working in academia on community-based obesity prevention; KAB has led the evaluation of large complex state-wide community-based obesity prevention interventions > 10 years and has spent the last 4 years as an implementation specialist in community-based systems approaches to childhood obesity. CB has 27 years of research experience in community-based obesity prevention and public health medicine. SA has over 20 years of research experience in community-based prevention, and 10 years specifically working with communities utilising systems methodologies, and co-developed innovative software for use in building CLDs and reporting actions over time.

Development of the definitions was iterative. Initially the core team (ADB, KAB, JW, PF) provided a draft translation. This was presented to CB and SA for feedback and re-worked. The core team then mapped actions to the draft translations and found several items lacked clarity. Wording was again altered and further input from CB and SA was sought. In our third iteration, we invited input from an external reviewer with experience that spans mental health and wellbeing, physical activity, and disability. This external reviewer had not been involved in the translation process. This process was designed to test alignment between an external party actions mapped by the external reviewer with those of the core research team. This identified key ‘gaps’ in framework alignment which led to a fourth iteration and re-wording, followed by a further iterative round of expert consultation. What is presented here is the fifth iteration of our translation. The translations are focussed on public health because all authors currently work in public health, and public health projects were used to trial the translation.

Twenty-five meetings (each ~ 2 h duration) were conducted between 21/09/2020 and 31/05/2021 with the core research team. First, definitions of M12 were carefully considered. Drawing from both practitioner expertise with participatory community-based prevention work and academic expertise, new consensus translations (definitions) were constructed based upon each level of M12. We then identified examples of each intervention point.

Testing the new language/proof of concept

To demonstrate the types of actions that sit under the Public Health framework (PH12) leverage points, action registers from three independent community-based systems approaches addressing obesity conducted in Victoria were examined by the author team described above.

The action registers were spreadsheets of documented actions implemented in each community as recorded by the project officer. In keeping with the philosophy of co-designed actions, each community was encouraged to register actions that were important to them. An implementation specialist embedded in the community (PF) coded actions against the PH12. A diverse range of actions were purposefully selected from a pool of over 300. These were presented back to the core research team in a matrix to discuss. This matrix consisted of M12, community, action, concepts for new public health language and comments were noted from discussion between the research team. Continual referral to the original M12 framework and example actions as described was conducted. A consensus agreement was made within the team on which of the 12 leverage points each action best aligned, and which public health language best described the leverage point.

Results

Table 1 captures our public health translation of the Donella Meadows 12 system leverage points [16].

Example actions of the leverage points are shown in Table 2. Future work will map ~ 200 full actions to the PH12.

Discussion

We translated the M12 framework for public health to enable public health practitioners and researchers to categorise actions according to level of impact.

Multiple attempts across various disciplines have adapted the M12 to contemporary study areas [27] though typically with academic, discipline specific language. The Intervention Level Framework (ILF) acknowledged the difficulty of applying M12 to public health and collapsed them into the five level ILF framework [18, 20]. The ILF comprises (from highest to lowest impact): paradigm, goals, system structures, feedbacks and delays, and structural elements. Specific to school settings, McIssac [28] further summarised data aligned to the ILF into three themes of intervention points within the school food system (from highest to lowest impact): purpose and values, system regulation and interconnections, and actors and elements. The ILF has been used successfully utilised to code pre-conference reading, and high-level documents (i.e. government, health, medical reports) related to obesity efforts/strategies to help influence future policy and planning [18]. However, we found no publications where researchers utilised the ILF to categorise system level obesity prevention actions implemented in real world interventions although some work is pending [29]. Nobles et al. [19] challenged the reductionist approach inherent in the ILF and proposed the Action Scales Model (ASM), which aligns with both the ILF and M12. The four levels of the ASM are: beliefs (levels 1 and 2 in M12), goals (level 3 in M12), structures (levels 4-9 in M12), and events (levels 10-12 in M12). The strength of the ASM compared to the ILF is it considers comprehensively how its levels interact and combine to create public health change. However, the ASM shares the same drawback in the ILF in that by reducing M12 to four categories for the sake of simplification, nuanced insights from the original M12 are lost.

Given the work of Malhi [20], Johnston [18], McIssac [28] and Nobles [19] to operationalise M12 with the specified intent to improve usability for public health and policy practitioners with each iteration, why create something new? We argue that we have not created something new but translated the M12 into language useful for public health practice. Rather than reduce the number of levels, we embraced the challenge and the complexity of M12, and the difficulty of interpreting and operationalising the work of a system dynamics expert from a non-public health field into obesity prevention. To deliberately maintain the finesse and nuance of the 12 levels of M12, we engaged with cross-sector expertise. We consider much of the nuance of the original M12 is lost in other translations. This loss of nuance may assist in mapping actions in the short term but may hinder capacity to measure change over time, to fully understand the different impacts of various level actions, and to perform a deep evaluation of what drives systems change.

Another potential advantage of PH12 is helping communities decide ‘what’ to implement once actions have been identified. By offering more levels, communities and practitioners can align and prioritise actions more comprehensively than with the other available systems scales (i.e., choosing between level 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9 actions rather than picking between a big group of actions at the “Structures” level in the ASM). In this way PH12 intersects with the growing field of implementation science, defined as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other [evidence based practices] EBPs into routine practice …” [30].

Public health implications

Durham [31] utilised the ILF to explore systems change in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ear health. We concur with Durham et al. [31] that the implementation of system science would be advanced through an identification of the number of actions and the levels of actions required to facilitate systems change. We consider by maintaining 12 levels, we provide a more nuanced opportunity for such analysis. The PH12 definitions will support public health practitioners and researchers to examine the gaps in implementation by identifying ‘levels’ where no action is planned.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the diverse team experience (i.e., practitioner in community, systems dynamicist, researcher (implementation and evaluation) lenses) with community-based systems approaches to obesity prevention. The PH12 translations were informed by expertise drawn from related fields such as social work, community development and allied health, potentially widening the reach of the proposed PH12. Having an external public health reviewer test the translation provided confirmation that PH12 could be used without being an implementation expert. Testing the framework outside of public health is beyond the scope of the current paper; and testing outside research-based settings is planned. We, like Meadows, offer this as a step forward in the identification of targeted actions for systems change and invite ongoing critique and improvements with other researchers and practitioners.

This newly translated PH12 framework is user friendly and will be a guiding tool that practitioners, researchers, key community stakeholders and policy makers can use to decide where to invest time, effort, and resources. Future work rigorously testing the framework by other CBSD theorists and practitioners, public health researchers and practitioners on the ground implementing community-based systems thinking approaches to address complex problems is recommended and we encourage external validation by experts outside of Australia and in other fields.

Conclusions

To date little guidance for practitioners and researchers exists regarding where to target actions for community-led public health action such as obesity prevention. We have translated M12 into PH12 to allow improved operationalisation of the 12-level framework through a public health lens. Potentially, a deeper understanding of the potential consequences of action to address complex health problems can be achieved.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASM:

-

Action Scales Model

- CBSD:

-

Community-based system dynamics

- CLD:

-

Causal loop diagram

- GLOBE:

-

Global Obesity Centre

- GMB:

-

Group model building

- ILF:

-

Intervention Level Framework

- M12:

-

Meadows 12

- PH12:

-

Public Health 12 framework

- RESPOND:

-

Reflexive Evidence and Systems interventions to Prevent Obesity and Non-communicable Disease

- WHO STOPS:

-

Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for Childhood Obesity

- YCHANGe:

-

Yarriambiack – Creating Healthy, Active, Nourished Generations

References

Ison R. Systems practice: how to act in a climate change world. London: Springer; 2010.

Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390:2602–4.

Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32:513–31.

Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, Atkins VJ, Baker PI, Bogard JR, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2019;393:791–846.

Hovmand P. Community based system dynamics. New York: Springer; 2014.

Siokou C, Morgan R, Shiell A. Group model building: a participatory approach to understanding and acting on systems. Public Health Res Pract. 2014;25(1):e2511404.

Sterman JD. Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:505–14.

Cilenti D, Issel M, Wells R, Link S, Lich KH. System dynamics approaches and collective action for community health: an integrative review. Am J Community Psychol. 2019;63:527–45.

Sanigorski AM, Bell AC, Kremer PJ, Cuttler R, Swinburn BA. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in children through community capacity-building: results of a quasi-experimental intervention program, Be Active Eat Well. Int J Obes. 2008;32:1060–7.

Millar L, Kremer P, de Silva-Sanigorski A, McCabe MP, Mavoa H, Moodie M, et al. Reduction in overweight and obesity from a 3-year community-based intervention in Australia: the ‘It’s Your Move!’ project. Obes Rev. 2011;12(Suppl 2):20–8.

Bolton KA, Kremer P, Gibbs L, Waters E, Swinburn B, de Silva A. The outcomes of health-promoting communities: being active eating well initiative—a community-based obesity prevention intervention in Victoria, Australia. Int J Obes. 2017;41:1080–90.

Hovmand PS. Group model building and community-based system dynamics process. Community based system dynamics. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 17–30.

Wikibooks. Scriptapedia. 2020 [updated 2020 May 27]. Available from: https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Scriptapedia. Cited 2021 September 18.

Hovmand PS, Andersen DF, Rouwette E, Richardson GP, Rux K, Calhoun A. Group model-building ‘scripts’ as a collaborative planning tool. Syst Res Behav Sci. 2012;29:179–93.

Scott RJ, Cavana RY, Cameron D. Recent evidence on the effectiveness of group model building. Eur J Oper Res. 2016;249:908–18.

Meadows DH. Thinking in systems: a primer. White River Junction: Chelsea Green; 2008.

Jalali MS, Rahmandad H, Bullock SL, Lee-Kwan SH, Gittelsohn J, Ammerman A. Dynamics of intervention adoption, implementation, and maintenance inside organizations: the case of an obesity prevention initiative. Soc Sci Med. 2019;224:67–76.

Johnston LM, Matteson CL, Finegood DT. Systems science and obesity policy: a novel framework for analyzing and rethinking population-level planning. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1270–8.

Nobles JD, Radley D, Mytton OT. The Action Scales Model: a conceptual tool to identify key points for action within complex adaptive systems. Perspect Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/17579139211006747.

Malhi L, Karanfil Ö, Merth T, Acheson M, Palmer A, Finegood DT. Places to intervene to make complex food systems more healthy, green, fair, and affordable. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2009;4:466–76.

Allender S, Owen B, Kuhlberg J, Lowe J, Nagorcka-Smith P, Whelan J, et al. A community based systems diagram of obesity causes. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0129683.

Allender S, Orellana L, Crooks N, Bolton K, Fraser P, Brown AD, et al. Four-year behavioural, health related quality of life and BMI outcomes from a cluster randomized whole of systems trial of prevention strategies for childhood obesity. Obesity. 2020;29:1022–35.

Whelan J, Strugnell C, Allender S, Korn AR, Brown AD, Orellana L, et al. Protocol for the measurement of changes in knowledge and engagement in the stepped wedge cluster randomised trial for childhood obesity prevention in Australia: (Reflexive Evidence and Systems interventions to Prevent Obesity and Non-communicable Disease (RESPOND)). Trials. 2020;21:763.

Whelan J, Love P, Millar L, Allender S, Morley C, Bell C. A rural community moves closer to sustainable obesity prevention-an exploration of community readiness pre and post a community-based participatory intervention. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1420.

Johnston L. The intervention level framework: using thinking to address the complexity of childhood obesity prevention [master’s thesis]. Burnaby: Simon Fraser University; 2010.

Meadows D. Leverage points: places to intervene in a system. Hartland: The Sustainability Institute; 1999.

Fischer J, Riechers M. A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat. 2019;1:115–20.

McIsaac J-LD, Spencer R, Stewart M, Penney T, Brushett S, Kirk SF. Understanding system-level intervention points to support school food and nutrition policy implementation in Nova Scotia, Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(5):712.

Waterlander WE, Luna Pinzon A, Verhoeff A, den Hertog K, Altenburg T, Dijkstra C, et al. A system dynamics and participatory action research approach to promote healthy living and a healthy weight among 10-14-year-old adolescents in Amsterdam: the LIKE programme. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4928.

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):32.

Durham J, Schubert L, Vaughan L, Willis CD. Using systems thinking and the intervention level framework to analyse public health planning for complex problems: otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194275.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for childhood obesity (WHO STOPS childhood obesity): NHMRC Partnership Project GNT1114118. 2015 – 2020.

Reflexive Evidence & Systems interventions to Prevent Obesity & Non-communicable Disease (RESPOND): NHMRC Partnership Project GNT 1151572. 2019-2022.

Yarriambiack – Creating Healthy, Active, Nourished Generations (YCHANGe): Rural Northwest Health Service, Victorian Royal Flying Doctors Service, and Victorian Department of Health and Human Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KAB, JW and ADB conceived the study. KAB, JW, ADB, PF, CB and SA worked together on the translation. All authors contributed to identify interventions relevant to each leverage point. KAB, JW and ADB wrote the initial draft. All authors contributed to all drafts and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained for all studies from which actions are drawn for inclusion in this study. WHO STOPS: Deakin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (DU-HREC) 2014-279, DU-HREC 2013-095, Deakin University’s Human Ethics Advisory Group-Health (HEAG-H), HEAG-H 155_2014, HEAG-H 118_2017; RESPOND: HEAG-H 012019; YCHANGe: HEAG-H 80_2016. For this manuscript, no human participants were recruited.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bolton, K.A., Whelan, J., Fraser, P. et al. The Public Health 12 framework: interpreting the ‘Meadows 12 places to act in a system’ for use in public health. Arch Public Health 80, 72 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00835-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00835-0