Abstract

In this paper a new approach is taken to find the exact solutions for generalized unsteady magnetohydrodynamic transport of a rate-type fluid near an unbounded upright plate and is analyzed for ramped wall temperature and velocity with constant concentration. The vertical plate is suspended in a porous medium and encounters radiation effects. Solutions based on special functions are obtained using an integral transform for an unsteady MHD Maxwell fluid in the presence of ramped velocity, temperature and constant concentration. The relations for Nusselt number and skin-friction coefficient are efficiently computed to precisely estimate the rate of heat transfer at the boundary and the shear stress. Results are also discussed in detail and demonstrated graphically using software to comprehensively analyze the dynamics of the proposed problem, and the physical impact of several system parameters, such as magnetic field M, Prandtl number Pr, the relaxation time λ, dimensionless time τ, Schmidt number Sc, Mass and Thermal Grashof numbers Gm and Gr, respectively, is studied. Furthermore, solutions for some recently published work are compared with the current study that endorses the authenticity of our derived results and proves that those investigations are limiting or special cases of the current problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The study of non-Newtonian fluids is a very interesting topic for many researchers due to its wide application in modern technologies and many industrial sectors. The non-Newtonian fluids deal with the problems related to the chemical engineering, polymers, petroleum, paints, pharmaceutical, plastics, and food-processing industries. Furthermore, these type of models also deal with fluids such as biological materials, ketchup, polymeric liquids, motor oils, personal care items (shampoo, creams, toothpastes) and complex mixtures, etc. However, in the literature, different types of fluid models exist included rate type, differential and integral models. Many researchers have addressed the rate-type fluid model, because from the research point of view it is more applicable, having both elastic effects and memory. Hence, in the present work, rate-type models are recognized as a Maxwell model. Furthermore, this type of model was first developed by Maxwell to estimate the air viscoelastic characteristics [1]. Also, Jordan et al. [2] studied solutions that are exact for the Stokes problem of the first type, including the Maxwell model also. Moreover, Fetecau et al. [3] explored the Stokes problem of the second type by assuming flow of a fluid placed on the surface of an infinite plate that is vacillating in the plane. Furthermore, the model generated by Maxwell is known as an uncomplicated model operated to assess the rheological performance of fluids and have features of both viscosity and elasticity. Fetecau [4] investigated the exact solution for an infinite vertical surface. The effects of thermophoresis and chemically reactive impacts on the flow of Maxwell fluids were studied by Noor [5]. It is the case that when heat is extracted from a high-temperature wall through a fluid having a certain movement such a mechanism is termed heat convection (advection). This mechanism interacts by molecular diffusion and the motion of the fluid on the basis of natural as well as forced convection. This is due to convective-heat transfer that transpires when the surface temperature varies from that of the encompassing fluid [6]. Solangi et al. [7] investigated the unique heat-conduction properties for the enhancement of concentration. The focus in this work was to discuss the particle-size control for heat exchange and mass-concentration behavior on fluids. Soomro et al. [8] carried out a typical analysis of stretching a surface to develop the heat transfer for the flow of a non-Newtonian nanofluid. To study the physical aspects, numerical computation was used on the governing equations based on finite-difference schemes to describe heat-transfer phenomena. Shafiq et al. [9] conducted an interesting study on the magnetohydrodynamic convective flow to explore the transfer rate of heat, motile microorganisms and mass. They emphasized the parametric study of the problem for Brownian motion, buoyancy forces, thermophoretic, magnetic field and Newtonian heating for temperature and concentration. Kashif et al. [10] carried out a dual thermal analysis to determine the role of temperature dissimilarity versus the temperature or time by using a suspension of nanoparticles. The core objective of this study was to highlight the problem through fractional operators and special functions. Heat transmission over a stretched sheet based on the magnetohydrodynamic two-dimensional Casson fluid flow was observed by Hamid et al. [11]. They examined the linear convected heat effects on two-fold solutions in which numerical stability was discussed for the dual results from the governing equation of the problem. Abro et al. [12] suggested a fractional study for thermal radiation of a Jeffery fluid and educed the subsolutions from fluid motion of the second grade with and without a magnetic field. The thermal properties of the governing equations were treated by an integral-transform approach. Sheikholeslami et al. [13] observed a magnetizable hybrid fluid in the core of a circular cavity with two heaters in circular form subjected to the carbon nanotubes. Their focus was to create the magnetic fields by wires via an electrical current. Abdelmalek et al. [14] applied a hybrid technique known as the Control Volume Finite Element Scheme to the curved circular heater with nanosized particles on convective-heat transmission. They suggested the finding and concluded that the conformation of the curved heater played an essential role to manage the heat-transfer rate and control the convectional flow within the enclosure. Kashif [15] applied surface-modification technology to analyze the thermodissipation effects on the time-dependent natural-convection flow of fluid. A finite Fourier sine transform, Laplace and fractional techniques were applied to the governing equations to show the typical and rheological properties of the problem. Although the studies on heat and transfer analysis will be continued the relevant studies can be observed therein in categorical format as: heat transfer via analytical approaches [16, 17, 29–32], heat transfer via numerical approaches [18, 19, 33–36], heat transfer via fractional calculus approaches [20, 21, 37, 38] and heat transfer via multidimensional approaches [22, 23, 25, 26, 39, 40]. Motivated by the above consideration, the main theme of this paper is to assess the significance of convective heating and variable heat source on the azimuthal oscilatroy MHD convective flows developed in a cylindrical Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium filled by a radiating second-grade fluid.

Talha Anwar et al. [24] recently, discussed the same problem for a different fluid model without analyzing the diffusion equation, and determined the approximate result for the proposed problem by using the Laplace transformation technique and Durbin’s numerical algorithm. The work introduced in this paper is new. In this model, we added a concentration equation and analyzed its effects on the velocity profile. Based on the aforesaid literature, the object of this exploration is to establish the exact expressions for velocity, concentration and energy equations, in terms of a generalized Lorenzo–Hartley function known as the G-function, of the considered problem and accomplish a comparison with the results obtained by Talha Anwar et al. [24]. In solving the differential equations (DEs) with the help of the Laplace transform method (LT), the inverse integral transform is not trivial. In this regard we have to introduce some special functions. For example, a Mittag–Leffler function, a Robotnov and Hartley function, a Lorenzo and Hartley generalized R function, a generalized G function, etc. Such functions produce a direct solution and give important interpretations for the fundamental linear integer-order DEs and corresponding IVPs. These functions are helpful in the solution of the problems and more notably in the solution of differential equations. Furthermore, the consequences of different related physical parameters, such as relaxation time parameter λ, grashof number Gr, magnetic field M, dimensionless time τ, Schmidt number Sc, mass Grashof number Gm and Prandtl number Pr, on nondimensional velocity, concentration and temperature are discussed in detail and demonstrated graphically using appropriate software.

2 Mathematical model

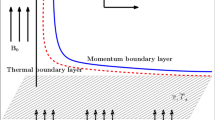

Let us assume that the unsteady MHD, natural convection, incompressible, time-dependent, viscous motion of a Maxwell fluid is near an infinite upright plate embedded in a permeable medium with constant concentration and ramped conditions on temperature. In this case, consider the cartesian coordinates system \((x,y)\), the plate is placed in the plane such that the x-axis is vertically oriented and the y-axis is in the normal direction. At the end of the wall, temperature, velocity and concentration are assumed to be time dependent within certain limits of time, identified as the characteristic time; velocity, temperature and concentration after that time attain constant values of velocity \(u_{0}\), temperature \(T_{\infty }\) and concentration \(C_{\infty }\). The physical quantities of the model’s flow that is under consideration is described in Fig. 1. The principal governing partial differential equations with small Reynolds number and the usual Boussinesq’s approximation are given as [25, 26]:

with initial and boundary conditions of:

where

and

Introducing the set of dimensionless quantities:

After employing the dimensionless quantities, and ignoring the asterisk ∗ notation, the following partial differential equations in dimensionless form are derived as:

with conditions in dimensionless form:

where

and

3 Solution of the problem

To obtain the solution of the considered problem, the Laplace transformation technique was employed.

3.1 Exact solution of heat profile

Applying the Laplace transformation technique to write the solution of Eq. (11) with conditions as Eqs. (14), (15), (16), we have

with

and its solution is given by

we applied boundary conditions for temperature given by Eq. (18) to determine the unknown constants and obtain:

which can be written as

To obtain the required solution of Eq. (21), the Laplace inverse transformation was used, which is written as:

with

where \(g(\Phi )\) represents a standard Heaviside function and \(\Phi =\tau -1\).

3.1.1 Nusselt number

An expression for the Nusselt number to efficiently forecast the generalized rate of heat transfer corresponding to ramped conditions is evaluated as:

where \(H(\tau -1)\) represents a standard Heaviside function.

3.2 Exact solution of mass profile

Solving Eq. (13) using Eqs. (14), (15) and (16), and employing the Laplace transformation technique, the resulting equations are written as:

with

the solution in general form is

the values of constants \(c_{1}\) and \(c_{2}\), conditions are implemented as given in Eq. (26) for concentration, so

To obtain the solution, taking the inverse Laplace transformation, we have:

The following result, which exists in the literature, is used:

3.3 Exact solution of velocity profile

The solution of Eq. (10) by using a Laplace transform, is:

by using Eqs. (21), (28) to determine the values \({\bar{\theta } (\psi ,s )}\) and \({\bar{C} (\psi ,s )}\), then Eq. (32) has the general form of the solution, which is represented as:

Applying \({\bar{u}(\psi ,s)}\rightarrow 0\), as \(\psi \rightarrow \infty \) and \({\bar{u}(0,s)}=\frac{1-e^{-s}}{s^{2}}\), to determine the values of unknowns \(c_{3}\) and \(c_{4}\), we obtain:

To find the Laplace inverse of Eq. (34), we rearrange the above equation as:

Employing an inverse Laplace transformation on Eq. (35), the obtained solution is written as:

with

where \(g(\Phi )\) represents a standard Heaviside function and \(\Phi =\tau -1\), also

with \(\epsilon = \frac{\Pr - b}{\lambda }\) and \(\delta = \frac{Sc - b}{\lambda }\), the function \(G_{h,b,l}(.,\tau )\) used in the above expressions is known as the generalized Lorenzo–Hartley function and is defined as \(\mathscr{L}^{-1} \lbrace \frac{s^{b}}{(s^{h}-j)^{l}} \rbrace =G_{h,b,l}(j,\tau )\); \(\operatorname{Re}(hl-b)>0\), \(\operatorname{Re}(s)>0\), \(\vert \frac{j}{s^{h}} \vert <1 \).

3.4 Solution of shear stress

In the industrial and mechanical fields, wall shear stress is of indispensable significance and increasing shear stress is considered as a disadvantage. To estimate the wall shear stress and skin-friction coefficient for a Maxwell fluid we employ a Laplace transform on Eq. (12), and we have:

To determine the value of \(\frac{d\bar{u} (\psi ,s )}{d{\psi }}\), differentiating Eq. (34) with respect to ψ yields:

where \(\S = a + \lambda s^{2} + bs\).

Inserting Eq. (51) into Eq. (50), gives the expression for shear stress:

The skin-friction coefficient is estimated as

Since the solution given in Eq. (52) and Eq. (53) contains complex terms of the Laplace parameter s, to derive the solution in real time τ, we applied the numerical inversion method known as the Durbin Method [27].

4 Limiting cases

We obtain the same expression for the velocity profile with ramped temperature, without considering the effect of the mass Grashof number, i.e., \(Gm=0\), as obtained by Talha Anwar et al. [24]. Also, we derive the same result for the velocity profile and temperature distribution of a viscous fluid when \(\lambda = 0\) and \(Gm=0\), etc. [28]. This proves the authenticity of our work compared with the existing literature.

5 Results and discussion

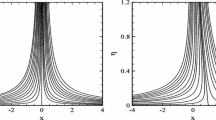

In this work, we investigated the effects of constant concentration, ramped temperature and velocity, on the unsteady MHD convective flow of a Maxwell fluid. The exact expressions for nondimensional velocity, concentration and energy equations, in terms of the generalized Lorenzo–Hartley function known as the G-function, are established for the considered problem. The results are demonstrated graphically, for better understanding of the physical significance of the proposed problem, by considering several values of different parameters involved in the problem, like Prandtl number ‘Pr’, the relaxation time ‘λ’, dimensionless time ‘τ’, Schmidt number ‘Sc’, mass Grashof number ‘Gm’ and Grashof number ‘Gr’. For various values of t the behavior of temperature, concentration and velocity are portrayed in Figs. 2 to 11.

Figure 2 represents the influence of τ on concentration and the energy equation. It is noted that increases in time enhanced the temperature and concentration profile of the moving fluid. Concentration and energy are both rising functions of time.

Figure 3 describes the temperature variation for various values of Pr; it is shown that when the value of Pr increases the result is a decrease in the temperature. Generally, the thermal outline layer thickness decreases rapidly, corresponding to high values of Pr. Hence, increasing the value of Pr improves the boundary thickness, which causes the energy profile to slow down linearly.

Figure 4 illustrates the behavior of concentration for various values of Schmidt number Sc; it is deceptive that for maximum values of Sc, a decay in concentration profile is noted. This is due to the reduction in the outline layer of concentration that occurs corresponding to the increase in the value of the Schmidt number. The involvement of the concentration factor of fluid velocity on the fluid flow is very important and it cannot be overlooked.

Figure 5 describes the effects of Gm. The mass Grashof number is generally defined as the ratio of mass buoyancy force to viscous force, which causes unrestricted convection. It is noted that the velocity is enhanced in the case of increasing Gm.

Figure 6 shows the impacts of Gr. It is noted that the velocity is elevated due to the higher value of Gr. Thermal Grashof number is the proportion of thermal buoyancy force to viscous force, which causes free convection.

Figure 7 illustrates the variation in the velocity field for different values of M; it can be observed that the fluid velocity declines when M is maximum, which causes an increase in the Lorentz force that acts as a dragging force along with allied forces that leads to a fall in the fluid velocity. Also, this force becomes weaker when this is far from the plate surface and eventually fluid flow stops.

Figure 8 represents the influence of Pr on the momentum equation. It is noted that increases in Prandtl number reduce the velocity of the moving fluid. The outline layer of the velocity profile becomes thicker due to the small rate of thermal diffusion, Pr dominates the relative thickness of the boundary layers of momentum in heat-transfer problems.

In Fig. 9 the action of Sc on the velocity profile is displayed and shows that the flow will decrease as Sc increases. Physically, the Schmidt number Sc is mathematically defined as the ratio of momentum to mass diffusivity. This layer of momentum diffusivity of the fluid is more viscous, and as a result velocity decreases.

Figure 10 shows the behavior of the Maxwell parameter in that the velocity decreases as the value of λ increases. This is due to a low Maxwell shear stress impact, parameter value variation of the term λ is not too significant because of the low effect of activation energy.

Figure 11 shows the momentum field to analyze the effect of τ. A rise in the velocity profile appears on increasing the value of τ. It has been observed that velocity increases as a function of time.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we analyze the effects of ramped temperature and velocity with constant concentration on unsteady MHD convective flow on Maxwell fluids. The governing partial differential equation is inscribed into a dimensionless form and the technique of Laplace transformation is used to establish the analytical solution for the velocity profile, concentration and energy equations, in terms of the generalized Lorenzo–Hartley function known as the G-function, for the proposed problem. The mathematical expressions for skin-friction coefficient and Nusselt number are also given. Also, for various parameters, i.e., Prandtl number Pr, Maxwell parameter λ, dimensionless time τ, Schmidt number Sc, magnetic field M, mass and thermal Grashof numbers Gm and Gr, respectively, the impacts of all these parameters on fluid velocity field, constant concentration and ramped wall temperature with the help of graphical illustrations are analyzed. Some noteworthy remarks and concluding results from this work are:

-

It is shown that the temperature field declines with larger values of Pr. It is also noted that the concentration reduces for increasing values of Sc.

-

It is determined that concentration, temperature and velocity profiles are increased as τ increases.

-

It is shown that for higher values of M and λ the fluid velocity is decreased.

-

Increasing values of the Grashof numbers Gr and Gm stimulate the velocity distribution.

-

The accumulative values of the parameters Sc and Pr decrease in the velocity distribution noted.

-

The involvement of the concentration factor of fluid velocity in the fluid movement is significant and cannot be overlooked.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

Maxwell, J.C.: Iv. on the dynamical theory of gases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 157, 49–88 (1867)

Jordan, P., Puri, A., Boros, G.: On a new exact solution to Stokes’ first problem for Maxwell fluids. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 39, 1371–1377 (2004)

Fetecau, C., Jamil, M., Fetecau, C., Siddique, I.: A note on the second problem of Stokes for Maxwell fluids. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 44, 1085–1090 (2009)

Fetecau, C., Fetecau, C.: A new exact solution for the flow of a Maxwell fluid past an infinite plate. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 38, 423–427 (2003)

Noor, N.F.M.: Analysis for MHD flow of a Maxwell fluid past a vertical stretching sheet in the presence of thermophoresis and chemical reaction. World Acad. Sci., Eng. Technol. 64, 1019–1023 (2012)

Bhojraj, L., Abro, K.A., Abdul, W.S.: Thermodynamical analysis of heat transfer of gravity driven fluid flow via fractional treatment, an analytical study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-020-09429-w

Solangi, K.H., Kazi, S.N., Luhur, M.R., Badarudin, A., Amiri, A., Sadri, R., Zubir, M.N.M., Gharehkhani, S., Teng, K.H.: A comprehensive review of thermo-physical properties and convective heat transfer to nanofluids. Energy 89, 1065e86 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.06.105

Soomro, F.A., Haq, R.U., Khan, Z.H., Zhang, Q.: Passive control of nanoparticle due to convective heat transfer of Prandtl fluid model at the stretching surface. Chin. J. Phys. 55(4), 1561–1568 (2017)

Shafiq, A., Hammouch, Z., Sindhu, T.N.: Bioconvective MHD flow of tangent hyperbolic nanofluid with Newtonian heating. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 133, 759–766 (2017)

Abro, K.A., Chandio, A.D., Abro, I.A., Khan, I.: Dual thermal analysis of magnetohydrodynamic flow of nanofluids via modern approaches of Caputo–Fabrizio and Atangana–Baleanu fractional derivatives embedded in porous medium. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 135, 2197–2207 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-018-7302-z

Hamid, M., Usman, M., Khan, Z.H.: Dual solutions and stability analysis of flow and heat transfer of Casson fluid over a stretching sheet. Phys. Lett. A 383, 2400–2408 (2019)

Abro, K.A., Irfan, A.A., Sikandar, M.A., Ilyas, K.: On the thermal analysis of magnetohydrodynamic Jeffery fluid via modern non integer order derivative. J. King Saud Univ., Sci. 31, 973–979 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2018.07.012

Sheikholeslami, M., Mehryan, S.A.M., Shafee, A., Sheremet, M.A.: Variable magnetic forces impact on magnetizable hybrid nanofluid heat transfer through a circular cavity. J. Mol. Liq. 277, 388–396 (2019)

Abdelmalek, Z., Tayebi, T., Dogonchi, A.S., Chamkha, A.J., Ganji, D.D., Tlili, I.: Role of various configurations of a wavy circular heater on convective heat transfer within an enclosure filled with nanofluid. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 113, 104525 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104525

Abro, K.A.: A fractional and analytic investigation of thermo-diffusion process on free convection flow: an application to surface modification technology. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-019-00046-7

Reddy, M.G.: Heat and mass transfer on magnetohydrodynamic peristaltic flow in a porous medium with partial slip. Alex. Eng. J. 55, 1225–1234 (2016)

Shaheen, A., Asjad, M.I.: Peristaltic flow of a Sisko fluid over a convectively heated surface with viscous dissipation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 122, 210–227 (2018)

Kashif, A.A.: Numerical study and chaotic oscillations for aerodynamic model of wind turbine via fractal and fractional differential operators. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 1–15 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/num.22727

Memon, Q.M., Ali Abro, K., Anwar Solangi, M., Ali Shaikh, A.: Functional shape effects of nanoparticles on nanofluid suspended in ethylene glycol through Mittage-Leffler approach. Phys. Scr. 96(2), 025005 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/abd1b3

Riaz, M.B., Awrejcewicz, J., Rehman, A.U., Akgül, A.: Thermophysical investigation of Oldroyd-b fluid with functional effects of permeability: memory effect study using non-singular kernel derivative approach. Fractal Fract. 5, 124 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract5030124

Ali, A.K., Atangana, A.: Dual fractional modeling of rate type fluid through non-local differentiation. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 1–16 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/num.22633

Afridi, M.I., Qasim, M., Wakif, A., Hussanan, A.: Second law analysis of dissipative nanofluid flow over a curved surface in the presence of Lorentz force: utilization of the Chebyshev-Gauss-Lobatto spectral method. Nanomaterials 9(2), 195 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9020195

Rehman, A.U., Riaz, M.B., Akgul, A., Saeed, S.T., Baleanu, D.: Heat and mass transport impact on MHD second grade fluid: a comparative analysis of fractional operators. Heat Transf. 50, 7042–7064 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/htj.22216

Anwar, T., Kumam, P., Watthayu, W., Asifa: Influence of ramped wall temperature and ramped wall velocity on unsteady magnetohydrodynamic convective Maxwell fluid flow. Symmetry 12, 392 (2020)

Khan, I., Ali, F., Shafie, S.: Exact solutions for unsteady magnetohydrodynamic oscillatory flow of a Maxwell fluid in a porous medium. Z. Naturforsch. A 68, 635–645 (2013)

Khan, I., Shah, N.A., Mahsud, Y., Vieru, D.: Heat transfer analysis in a Maxwell fluid over an oscillating vertical plate using fractional Caputo-Fabrizio derivatives. Eur. Phys. J. 132, 194 (2017)

Durbin, F.: Numerical inversion of Laplace transforms: an efficient improvement to Dubner and Abate’s method. Comput. J. 17, 371–376 (1974)

Seth, G., Nandkeolyar, R., Ansari, M.S.: Effect of rotation on unsteady hydromagnetic natural convection flow past an impulsively moving vertical plate with ramped temperature in a porous medium with thermal diffusion and heat absorption. Int. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 7, 52–69 (2011)

Kashif, A.A., Jose, F.G.: Fractional modeling of fin on non-Fourier heat conduction via modern fractional differential operators. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-020-05243-6

Yin, C., Zheng, L., Zhang, C., Zhang, X.: Flow and heat transfer of nanofluids over a rotating disk with uniform stretching rate in the radial direction. Propuls. Power Res. 6, 25–30 (2017)

Imran, M.A., Riaz, M.B., Shah, N.A., Zafar, A.A.: Boundary layer ow of MHD generalized Maxwell fluid over an exponentially accelerated infinite vertical surface with slip and Newtonian heating at the boundary. Results Phys. 8, 1061–1067 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-020-09312-8

Kashif, A.A., Abdon, A.: Role of non-integer and integer order differentiations on the relaxation phenomena of viscoelastic fluid. Phys. Scr. 95, 035228 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ab560c

Wakif, A., Boulahia, Z., Mishra, S.R., Rashidi, M.M., Sehaqui, R.: Influence of a uniform transverse magnetic field on the thermohydrodynamic stability in water-based nanofluids with metallic nanoparticles using the generalized Buongiorno’s mathematical model. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133, 181 (2018)

Imran, M.A., Aleem, M., Riaz, M.B., Ali, R., Khan, I.: A comprehensive report on convective flow of fractional (ABC) and (CF) MHD viscous fluid subject to generalized boundary conditions. Chaos Solitons Fractals 118, 274–289 (2018)

Muhammad, A., Makinde, O.D.: Thermo-dynamic analysis of unsteady MHD mixed convection with slip and thermal radiation over a permeable surface. Defect Diffus. Forum 374, 29–46 (2017)

Bhatti, M.M., Rashidi, M.M.: Study of heat and mass transfer with Joule heating on magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) peristaltic blood flow under the influence of Hall effect. Propuls. Power Res. 6, 177–185 (2017)

Rehman, A.U., Riaz, M.B., Saeed, S.T., Yao, S.: Dynamical analysis of radiation and heat transfer on MHD second grade fluid. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 129, 689–703 (2021). https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2021.014980

Riaz, M.B., Abro, K.A., Abualnaja, K.M., Akgül, A., Rehman, A.U., Abbas, M., Hamed, Y.S.: Exact solutions involving special functions for unsteady convective flow of magnetohydrodynamic second grade fluid with ramped conditions. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 408 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03562-y

Kashif, A.A., Abdon, A.: Numerical and mathematical analysis of induction motor by means of AB–fractal–fractional differentiation actuated by drilling system. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 1(15) (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/num.22618

Rehman, A.U., Riaz, M.B., Awrejcewicz, J., Baleanu, D.: Exact solutions of thermomagetized unsteady non-singularized jeffery fluid: effects of ramped velocity,concentration with Newtonian heating. Results Phys. 26, 104367 (2021)

Acknowledgements

The Authors are highly thankful to the Lodz University of Technology and the Polish National Science Centre for the grant OPUS 18 No. 2019/35/B/ST8/00980.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Polish National Science Centre under the grant OPUS 18 No. 2019/35/B/ST8/00980.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors took part in the present research equally and significantly. JA: Data Curation, Data Analysis, Project Administration, Validation, Supervision; MBR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Final Editing; AUR: Validation, Investigation, Writing, Initial Writing, Visualization; MA: Formal Analysis, Software, Reviewing and Editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Riaz, M.B., Awrejcewicz, J., Rehman, A.U. et al. Special functions-based solutions of unsteady convective flow of a MHD Maxwell fluid for ramped wall temperature and velocity with concentration. Adv Differ Equ 2021, 500 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03657-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-021-03657-6