Abstract

In this paper, we use a new powerful technique of arbitrary-order fractional (AOF) characteristic method (CM) to solve the AOF hyperbolic nonlinear scalar conservation law (HNSCL) of time and space. We present the existence and uniqueness of this class of equations in time and one-dimensional space of fractional arbitrary order. We extend Jumarie’s modification of Riemann–Liouville and Caputo’s definition of the fractional arbitrary order to introduce some formulae (Appl. Math. Lett. 22:378–385, 2009; Appl. Math. Lett. 18:739–748, 2005). Then, we use these formulae to prove the main theorem. In the application section, we use the analytical technique that is presented in the theorem to solve examples that are given.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In recent decades, fractional differential equations (FDEs) have attracted the interest of many researchers in different fields such as physics, engineering, science, finance, and biology [3–10]. So, lots of attention has been given to the solution of fractional ordinary differential equations (FODEs) and fractional partial differential equations (FPDEs) [11–15]. Finding an exact solution analytically for FODEs and FPDEs is very difficult, sometimes impossible. Therefore, researchers implement numerical techniques and approximate solutions in most cases.

In recent years, considerable attention to time and spatial fractional differential equations (TSFDEs) has been growing rapidly. These problems are deduced by replacing the standard time derivative with time-fractional derivative, and they can be used to describe some physical and industrial processes such as super diffusion and sub-diffusion phenomena [16–23].

In the last two decades, variable-order fractional calculus (VOFC) has attracted many researchers in different fields of science. Ross and Samko introduced the idea of FVOC in 1993 [24, 25]. The mathematicians in pure and applied mathematics as well as researchers in physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering, are pursuing this topic. As it is well known, when the order of the fractional operator is variable, some phenomena in physics can be described better than in the case of constant order; for instance, in the diffusion process in an inhomogeneous or heterogeneous medium, or in the processes where the changes in the environment modify the dynamic of the particle [26–29]. Researchers have considered fractional derivatives of variable order, with α depending on variable t, which was introduced in [28]. We present one of the three types of Caputo fractional derivatives that are defined in the next section. We are going to extend some formulae from constant-order fractional derivative that were introduced by Jumarie [1] for the arbitrary-order fractional derivative. The order of the derivative is considered as a function \(\alpha (t)\) taking values on the open interval \((0, 1)\).

The theory of hyperbolic conservation laws arose almost fifty years ago [30, 31]. The unique features of this class of systems of partial differential equations (PDEs) had been identified long before. There are many phenomena in mathematical physics that are arising, and their mathematical models are in the form of hyperbolic conservation law. Conservation law problems were presented in the early book by Tyn Myint-U and Lokenath Debnath [30] in Chap. 13. Afterward, some papers have been published. Guo-chang Wu [31] studied a fractional linear conservation law problem that used a fractional characteristic method. Our aim in this paper is the development of this method to address the arbitrary-order fractional nonlinear hyperbolic conservation law. The term time homogeneous hyperbolic conservation law refers to first-order systems of PDEs in the divergence form

The state vector \(U= ( u_{1}, \ldots , u_{n} )^{T}\), with values in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\), is to be determined, and \(u_{i}\) is a function of the spatial variables \(( x_{1}, \ldots , x_{m} )\) and time t. The given functions \(\mathcal{H}\), \(c_{i}\), and \(\mathcal{G}_{i}\), where \(i=1, \ldots , m\), are the smooth maps from \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) to \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\). Also \(\alpha :\mathbb{R}\rightarrow ( 0,1)\) and \(\beta :\mathbb{R}\rightarrow ( 0,1 )\) where \(\alpha ( \tau )\) and \(\beta (\tau )\) are continuous. The symbol \(\partial _{t}\) stands for \(\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\), \(\partial _{x}\) stands for \(\frac{\partial }{\partial x}\), and \(\partial _{t}^{\alpha ( \tau )}\) is an arbitrary-order fractional derivative that will be defined in Sect. 3.

The considered problem (1.1) when \(\alpha = 1\) reduces to the classical conservation law, numerical approximations of which have been intensively studied. However, to the best of our knowledge, the analytical solution of time fractional conservation law has not been addressed yet. This article aims to fill the gap and investigates the analytical solution of (1.1). In the present paper, we adopt the fractional characteristic method (FCM), which is a very powerful technique that converts an FPDE to a system of FODEs, which makes it possible to solve (1.1). The FCM method was introduced by Guo-chang Wu [31], and it has been further developed to address the AOF hyperbolic conservation laws. Due to its efficiency in obtaining the exact solution, it becomes a very attractive method for seeking answers to differential equations. The feature of this technique in comparison to the other analytical solution is that it gives us the ability to check if the obtained solution is exact, by substituting the answer in the FPDE and showing it satisfies the differential equation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the definitions of VOF derivative and integral are given. In Sect. 3, we use the definition from the previous section and Jumarie’s paper to present the AOF derivative and integral formulae. In Sect. 4, we prove the existence and uniqueness of AOF NHSCL, and in this prosses, the analytic method to solve the AOF FHCL is presented. In Sect. 5, we implemented the analytical approach that is introduced in Theorem 1 to solve a few examples. Also, as a benchmark in Examples 1, 2, and 5, we show that the obtained solution satisfies the AOF NHCL. This test can be done for other cases too. Finally, a summary is given in the last section.

2 Preliminaries

2.1 Variable-order Caputo derivatives for functions of one variable

The generalization of the Caputo derivative from constant order to variable order of fractional differentiation is defined in [28]. Given \(\alpha (t) \in (0, 1)\), the left and right Caputo fractional derivatives of order \(\alpha (t)\) of a function \(x: [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) are defined by:

respectively, where \({}_{a} D_{t}^{\alpha ( t )} x ( t )\) and \({}_{t} D_{b}^{\alpha ( t )} x ( t )\) indicate the left and right Riemann–Liouville fractional derivatives of variable order \(\alpha ( t )\).

Definition 1

Riemann–Liouville fractional derivatives of variable order \(\alpha ( t )\)-type I: Given a function \(x: [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) and \(0<\alpha (t)<1\), then:

- 1.

Type I left Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative of variable order \(\alpha (t)\) is defined by

$$ {}_{a} D_{t}^{\alpha ( t )} x ( t ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha (t) ]} \frac{d}{dt} \int _{a}^{t} (t-\tau )^{-\alpha (t)} x ( \tau ) \, d\tau . $$(2.2) - 2.

Type I right Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative of variable order α(t) is defined by

$$ {}_{t} D_{b}^{\alpha ( t )} x ( t ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha (t) ]} \frac{d}{dt} \int _{t}^{b} (\tau -t)^{-\alpha (t)} x ( \tau ) \, d\tau . $$(2.3)

Definition 2

Type III Caputo fractional derivatives of variable order \(\alpha (t)\) [28]: Given a function \(x: [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) and \(0<\alpha (t)<1\), then:

- 1.

Type III left Caputo derivative of variable order \(\alpha (t)\) is defined by

$$ {}_{a}^{C} D_{t}^{\alpha ( t )} x ( t ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha (t) ]} \int _{a}^{t} (t-\tau )^{-\alpha (t)} x ' ( \tau ) \, d\tau . $$(2.4) - 2.

Type III right Caputo derivative of variable order \(\alpha (t)\) is defined by

$$ {}_{t}^{C} D_{b}^{\alpha ( t )} x ( t ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha (t) ]} \int _{t}^{b} (\tau -t)^{-\alpha (t)} x ' ( \tau ) \, d\tau . $$(2.5)

3 A definition for Riemann–Liouville and Caputo fractional arbitrary-order derivative

In the above definitions the variable t in \(\alpha ( t )\) and \(x(t)\) is the same, which leads to different types of definitions. However, now we would like to present a definition that has different variables for α and x. In this case, we will have only one definition for the Riemann–Liouville and Caputo variable-order fractional derivatives, so it is appropriate to name it arbitrary-order instead of variable-order fractional derivative.

Definition 3

Riemann–Liouville fractional derivatives of arbitrary order \(\alpha (t)\): Given a function \(f: [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) and \(\alpha:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow ( 0,1)\), where \(f ( x )\) and \(\alpha ( t )\) are continuous, then:

- 1.

The left Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative of arbitrary order \(\alpha (t)\) is defined by

$$ {}_{a} D_{x}^{\alpha ( t )} f ( x ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha ( t ) ]} \frac{d}{dx} \int _{a}^{x} ( x-\tau )^{-\alpha ( t )} f ( \tau ) \, d\tau . $$(3.1) - 2.

The right Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative of arbitrary order \(\alpha (t)\) is defined by

$$ {}_{x} D_{b}^{\alpha ( t )} f ( x ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha ( t ) ]} \frac{d}{dx} \int _{x}^{b} ( x-\tau )^{-\alpha ( t )} f ( \tau )\, d\tau . $$(3.2)

Definition 4

Caputo fractional derivatives of arbitrary order \(\alpha (t)\): Given a function \(f: [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) and \(\alpha:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow ( 0,1)\), where \(f ( x )\) and \(\alpha ( t )\) are continuous, then:

- 1.

The left Caputo derivative of arbitrary order α(t) is defined by

$$ {}_{a}^{C} D_{x}^{\alpha ( t )} f ( x ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha ( t ) ]} \int _{a}^{x} ( x-\tau )^{-\alpha ( t )} f ' ( \tau )\, d\tau . $$(3.3) - 2.

The right Caputo derivative of arbitrary order α(t) is defined by

$$ {}_{x}^{C} D_{b}^{\alpha ( t )} f ( x ) = \frac{1}{\varGamma [ 1-\alpha ( t ) ]} \int _{x}^{b} ( x-\tau )^{-\alpha ( t )} f ' ( \tau )\, d\tau . $$(3.4)

3.1 Some results based on the above definition

Considering Definitions 3 and 4, we can extend all the results from Jumarie’s paper 32 from the constant-order fractional derivative to the arbitrary-order fractional derivative by replacing α with \(\alpha (t)\). Therefore, we present the following results.

Definition 5

Let \(f:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) denote a continuous (but not necessarily differentiable) function, and let \(h>0\) indicate a constant discretization span. The forward operator \(FW(h)\) is defined by the equality (the symbol := means that the left-hand side is defined by the right-hand side)

Assume \(\alpha: \mathbb{R}\rightarrow ( 0,1 )\) and continuous, then the fractional difference of arbitrary order \(\alpha ( t )\) for \(f ( x )\) is defined by the expression

and its fractional arbitrary-order derivative is the limit

This definition is close to the standard definition of the derivative, and as a direct result, the \(\alpha ( t )\)th derivative of a constant, \(0<\alpha (t)<1\), is zero.

3.2 Modified Riemann–Liouville derivative

Definition 6

([32])

Revised Riemann–Liouville definition: Based on Definition 4, its fractional derivative of arbitrary order \(\alpha (t)<0\) is defined by

For \(\alpha (t)\geq 0\), we write

and we can write

Also, for \(n\in \mathbb{N}\),

therefore, we have

The difference between (3.8) and (3.9) is that the latter contains the constant \(f ( 0 )\), while the first one does not. Equation refers to the modified Riemann–Liouville derivative, the constant of which was introduced by Jumarie.

Caputo’s definition can be presented as

instead of Definition 2, thus, it assumes explicitly that \(f(x)\) is differentiable.

With this definition, Laplace’s transform \(L\{\cdot\}\) in [32] can be presented in the form of the arbitrary-order fractional derivative as follows:

3.3 Background on Taylor’s series of fractional order

3.3.1 The basic formula for one-variable functions

A generalized Taylor expansion of constant-order fractional, which applies to nondifferentiable functions (F-Taylor series) in [32], can be generalized to the Taylor expansion of arbitrary-order fractional applicable to nondifferentiable functions as follows.

Proposition 1

Assume that the continuous function\(f :R \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\)has a fractional derivative of order\(k\alpha (t)\)for any positive integerkand\(\alpha :\mathbb{R}\rightarrow ( 0,1 )\)and continuous, then the following equality holds:

where\(f^{ [ \alpha ( t ) k ]} ( x )\)is the derivative of variable order\(\alpha (t)k of f(x)\), and with the notation

where\(\varGamma (\cdot) \)denotes the Euler gamma function.

Let \(E_{\alpha ( t )} ( u )\) represent the Mittag-Leffler function defined by the expression

and \(D_{x}\) be the derivative operator with respect to x, then the above series can be written

This arbitrary-order fractional Taylor’s series does not hold with the standard Riemann–Liouville derivative, and it only applies to nondifferentiable functions.

Corollary 1

Assume that\(m < \alpha ( t ) \leq m + 1\), \(m \in N \setminus \{ 0 \} \), \(\alpha :\mathbb{R}\rightarrow \mathbb{R}_{+}\), and continuous and that\(f(x)\)has derivatives of orderk (integer), \(1 \leq k \leq m\). Assume further that\(f^{(m)} (x)\)has a fractional Taylor’s series of arbitrary order\(\beta ( t ):=\alpha (t) - m \)provided by the expression

Then, integrating this series with respect to h provides

The arbitrary order of the derivation in \(f^{ [ k\beta (t)+m ]} (x)\) is very crucial and should be understood as \(D^{k\beta (t)} f^{(m)} (x)\), since we start with the fractional Taylor’s series of \(f^{(m)} (x)\).

3.3.2 Fractional Taylor’s series for two variable functions

The fractional Taylor’s series can be generalized in a straightforward way to two-variable functions to yield

Therefore, its total deferential for \(f ( x,y )\) would be

We denote that if f is one variable, then \(d^{\alpha ( \tau )} f ( x,y ) =d^{\alpha ( \tau ),0} f ( x,y )\).

3.4 Basic formulae for fractional derivative and integral

The formulae that we present will be used later to prove the theorem and to solve the problems that are given at the end.

3.4.1 A fractional derivative of compounded functions

Equation (3.14) provides a useful differential relation

or in terms of fractional difference, \(\Delta ^{\alpha ( t )} f \cong ( \alpha ( t ) ) ! \Delta f\).

Corollary 2

The following equalities hold:

therefore, if\(\alpha (t) = n + \theta (t)\), then the following properties are satisfied:

Remark 1

We denote that \(u(x)\) is nondifferentiable in (3.26) and (3.27) and differentiable in (3.28). \(v(x)\) is nondifferentiable, and \(f(u)\) is differentiable in (3.27) and nondifferentiable in (3.28).

The concept of differentiability and nondifferentiability is described by Jumarie for fractional constant order as follows [33]:

“Loosely speaking, there are two main trends in defining the framework of fractional calculus: on the one hand, the formal definition of the fractional derivative as an anti-integral; and on the other hand, the approach via fractional difference which works exactly like the standard (Leibniz) classical differential calculus.”

3.4.2 Integration with respect to \((dx)^{\alpha(t)}\)

The integral with respect to \(( dx )^{\alpha (t)}\) is defined as the solution of the fractional differential equation

which is provided by the following result.

Lemma 1

([2])

Let\(f(x)\)denote a continuous function, then the solution of equation (3.31) is defined by the equality

Proposition 2

We can also derive the following integrating formulae using (3.29) and (3.30):

4 Existence and uniqueness

We consider AOF HNSCL in time and one-dimensional space, which is defined as follows:

Here, we also use the following modified Riemann–Liouville derivative of the arbitrary-order fractional with parameters \(\alpha (\tau )\) and \(\beta ( \tau )\) that may not be the same:

Likewise, we consider in equation (4.1) the notations \(\partial _{t}^{\alpha ( \tau )} u(x,t):= {}_{0} D_{t}^{\alpha ( \tau )} u(x,t)\) for \(0 < \alpha ( \tau ) \leq \) 1 and, similarly, \(\partial _{x}^{\beta ( \tau )} u(x,t):= {}_{0} D_{x}^{\beta ( \tau )} u(x,t)\) for \(0 < \beta (\tau ) \leq 1\).

The solutions of the hyperbolic conservation law for \(\alpha = \beta = 1\) may be visualized as propagating waves. In the case of a nonlinear system, the profiles of compression waves progressively are getting steeper and finally break, generating jump discontinuities or shocks. Therefore, the theory applies only to weak solutions. This problem is complicated further by the fact that, due to weak solutions, uniqueness is lost. On the other hand, the classical characteristic method is an efficient and powerful technique that has been used to solve the initial value problem of FPDEs analytically by converting to a system of FODEs. It is well known that the method of characteristic has played an important role in mathematical physics. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no published work on proving the existence and uniqueness of equation (4.1); in this paper, we attempt to address this matter.

Theorem 1

Let us consider (4.1) where\(\mathcal{H} ( {u} ( {x},{t} ) ) = {\mathcal{G}} ( {u} ( {x},{t} ) ) ={u}({x},{t})\)

with the initial condition

Then this nonlinear initial value problem has a unique solution for all\(0<\alpha ( \tau )\), \(\beta (\tau ) \leq 1 \)such that the following conditions are satisfied:

- (i)

\(f,c \in C^{1}(\mathbb{R})\);

- (ii)

\(F (\xi ) = c(u(x, t)) = c(f (\xi ))\). Fandfare differentiable with respect toxandt;

- (iii)

ξis fractionally differentiable with respect toxandt;

- (iv)

\(\gamma t^{\alpha ( \tau )} F'(\xi ) + \beta (\tau ) \xi ^{\beta ( \tau )-1} \neq 0\)where\(\gamma = \frac{\varGamma (1+\beta ( \tau ))}{\varGamma (1+\alpha ( \tau ))}\);

- (v)

The given functions\(\mathcal{H} = \mathcal{G}= u\)are smooth maps.

Proof

The first part of the proof is to show existence. As the main tool, we use the method of arbitrary-order fractional characteristics.

The total differential of \(u(x,t)\) for (4.3) is given by

which leads to

Compare (4.3) with (4.5), equation (4.3) can be considered as the FODE

along with any member of the family curves ϒ which are the solution of

These curves ϒ are called the characteristic curves of equation (4.3). Thus the solution of (4.3) is reduced to the solution of a pair of simultaneous FODEs (4.6) and (4.7).

According to (4.6), which implies u is constant along each characteristic curve, each \(c(u)\) remains constant on ϒ, and the solutions of (4.7) form the family of the characteristic curves for (4.3) in the (x, t)-plane. It means that if the family of the curves ϒ can be obtained, then the general solution of (4.3) is obtained too. If we assume the initial point on the characteristic curve ϒ is given by ξ, it means the curve ϒ intersects \(t = 0\) at \(x = \xi \), then \(u (\xi , 0)\) = \(f(\xi )\) on the entire curve ϒ as shown in Fig. 1.

Thus, the family of the characteristic curves ϒ is the solution of the following FODEs:

and

However, equation (4.8) cannot be solved because c is a function of u, but (4.9) can easily be solved to obtain \(u =\mbox{constant}\), so \(u = f(\xi )\) on the entire curve of ϒ. Hence we have

Thus (4.8) leads to

where

From equation (4.11) and its integration, we have

which represents the characteristic curves (they are straight lines when \(\alpha = \beta = 1\)). Therefore equations (4.10) and (4.13) present the solution of the initial-value problem (4.3) in a parametric form

where

Now we show that solution (4.14) satisfies (4.3). We obtain the derivative of the 1st equation in (4.14) regarding x with an order of \(\beta ( \tau )\) and t with an order of \(\alpha ( \tau )\):

which leads to

where \(f '( \xi ) = f_{\xi } ' (\xi )\), \(\xi _{x}^{ [ \beta ( \tau ) ]} = D_{x}^{\beta ( \tau )} \xi \), and \(\xi _{t}^{ [ \alpha ( \tau ) ]} = D_{t}^{\alpha ( \tau )} \xi \). Then we find the derivative of the 2nd equation in (4.14) regarding x and t respectively with an order of \(\beta (\tau )\) and \(\alpha ( \tau )\):

which leads to

where \(F' ( \xi ) = F_{\xi } ' ( \xi )\). Eliminating \(\xi _{x}^{ [ \beta ( \tau ) ]}\) and \(\xi _{t}^{ [ \alpha ( \tau ) ]}\) we obtain

Substituting (4.19) in (4.3) we have

since \(F (\xi ) = c(f(\xi ))=c ( u ) \), equation (4.3) is satisfied provided \(\gamma t^{\alpha ( \tau )} F '(\xi )+\beta ( \tau ) \xi ^{\beta ( \tau )-1} \neq 0\). Solution (4.14) also satisfies the initial condition at \(t = 0\) since \(\xi =x\).

The second part of the proof is the uniqueness. Assume that \(u(x, t)\) and \(v(x, t)\) are two solutions of equation (4.3); therefore, they should satisfy solution (4.14), that is:

and

hence we can conclude from equations (4.20) and (4.21) that

Or we can say that on \(x^{\beta ( \tau )} = \gamma t^{\alpha ( \tau )} F ( \xi ) + \xi ^{\beta ( \tau )}\),

Equations (4.22) and (4.23) both imply the uniqueness. Therefore the proof is completed. □

5 Application

Systems of conservation laws naturally arise in a wide variety of applications. For instance, the study of transport in porous media, explosions, and blast waves, the propagation of waves in elastic solids, the flow of glaciers, and the separation of chemical species by chromatography. Some of these applications are presented below, and their solutions based on Theorem 1 are given.

Example 1

We consider the space-time arbitrary-order fractional equation for the transport in porous media, which \(c(u) = \mbox{constant} = k > 0\), and equation (4.1) can be written as follows:

Solution: According to the analytical method introduced in Theorem 1, we can obtain the following FODEs:

then

where \(\gamma ( \tau ) = \frac{\varGamma ( 1+\beta ( \tau ) )}{ \varGamma ( 1+\alpha ( \tau ) )}\). Using integrating formula (3.33), we have

By the initial condition, the constants \(C_{1}\) and \(C_{2}\) are obtained. Hence the parametric solution is

which leads to the solution

Concerning the initial condition (5.2), we have

Benchmark 1

(Example 1)

We show that (5.6) satisfies (5.1). We obtain the derivative of the 1st equation in (5.6) regarding x with an order of \(\beta ( \tau )\) and t with an order of \(\alpha ( \tau )\):

which leads to

where \(f' ( \xi ) = f_{\xi } ' (\xi )\). Then the derivative of the 2nd equation in (5.6) regarding x and t respectively with an order of \(\beta ( \tau )\) and \(\alpha ( \tau )\) is

By formula (3.24), we obtain

which leads to

equation (5.6) satisfies (5.1) provided \(\beta ( \tau ) \xi ^{\beta ( \tau ) -1} \neq 0\).

Solution (5.6) also satisfies the initial condition at \(t = 0\) since \(\xi = x\), and solution (5.6) is unique.

Suppose that \(u ( x,t )\) and \(v ( x,t )\) are two solutions. Then, on \(x^{\beta ( \tau )} = k t^{\alpha ( \tau )} + \xi ^{\beta ( \tau )}\)

therefore solution (5.6) is unique.

Remark 2

We consider the classic case of Example 1, where \(\alpha ( \tau ) = \beta ( \tau ) =1\), with an initial condition which is given as follows:

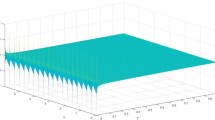

The solution of (5.16) is \(u ( x,t ) =f ( \xi )\) with \(x=kt+\xi \), which leads to \(u ( x,t ) =f ( x-kt ) = ( x-kt )^{2} +3 ( x-kt )\). The graph of u is plotted in Fig. 2.

(a) is the graph of the solution u in Example 1 where \(\alpha ( \tau ) =\beta ( \tau ) =1\). (b) is the graph of the solution u with the time fixed at \(t=1,2,3,4\), and 5

Remark 3

Let \(\alpha ( \tau ) =0.3\) and \(\beta ( \tau ) =0.8\), then the equation is

Its solution is given by

The graph of u is given in Fig. 3.

Example 2

Let us consider space-time arbitrary-order fractional inviscid Burger equation, which can be defined as follows:

with the initial condition

Solution: We obtain the following FODEs based on the technique that was presented in the theorem:

therefore

According to the theorem, u is a constant on characteristic curves in (5.20) where \(t=0\), \(u ( x,0 ) =f ( \xi )\), so we replace u in (5.20) by \(f ( \xi )\). Then we integrate

implementing formula (3.33)

where \(C_{1}\) and \(C_{2}\) are the integral arbitrary constants. Hence the parametric solution is

Benchmark 2

(Example 2)

We show that (5.23) satisfies (5.18). We obtain the derivative of (5.23) regarding x with an order of \(\beta ( \tau )\) and t with an order of \(\alpha ( \tau )\):

then

where \(f' ( \xi ) = f_{\xi } ' (\xi )\). Then the derivative of the 2nd equation in (5.23) regarding x and t respectively with an order of \(\beta ( \tau )\) and \(\alpha ( \tau )\) is

the derivative of (5.26) by using formula (3.24) is

which leads to

Since \(f ( \xi ) =u\), equation (5.18) is satisfied provided \(f ' ( \xi ) t^{\alpha ( \tau )} +\beta ( \tau ) \xi ^{\beta ( \tau ) -1} \neq 0\). Solution (5.23) satisfies the initial condition and is unique (similar to Benchmark 1).

Remark 4

The classic form of Example 2, where \(\alpha ( \tau ) = \beta ( \tau ) =1\), is the inviscid Burger equation, which is

The parametric solution based on Theorem 1 is

Since \(\xi = x -f ( \xi ) t=x -u t\), solution (5.32) can be presented by \(u ( x,t ) = f ( \xi ) =f(x -ut)\). This is an implicit relation that determines the solution of the inviscid Burgers’ equation when the characteristic curves do not intersect. If the characteristic curves do intersect, then a classical solution to the FPDE does not exist and leads to the formation of a shock wave.

Let \(f(x)= x^{2} +3x\) be the initial condition for (5.31), then

and the graphs of u are given in Fig. 4.

(a) and (b), respectively, with plus and negative signs are the graphs of the solution u in Example 2

Example 3

We are investigating a more complicated form of Example 1, the space-time of arbitrary-order fractional, which is

Solution: Comparing (5.33) with (4.1), we have

From total differential of u (4.4) we have

and

where \(\gamma (\tau ) = \frac{\varGamma ( 1+\beta ( \tau ) )}{\varGamma ( 1+\alpha ( \tau ) )}\). Integrating from equation (5.36) using formula (3.34), we obtain

and

\(C_{1}\) and \(C_{2}\) are the arbitrary integral constants. Hence the parametric solution is

Remark 5

Considering the classic case in Example 3, let \(\alpha ( \tau ), \beta ( \tau ) =1\)

The solution is

Therefore, \(u(x,t)= f(\ln ( e^{-t} - e^{-x} ) )\) and the graph of the solution u with the initial condition \(f ( x ) = x^{2} +3x\) for different values of \(\alpha ( \tau )\) and \(\beta ( \tau )\) is given in Fig. 5.

(a) and (b) are the graphs of the real and the imaginary parts of the solution u in Example 3, where \(\alpha ( \tau ) =\beta ( \tau ) =1\). (c) and (d) are the graphs of the real and the imaginary parts of u, where \(\alpha ( \tau ) =0.7\) and \(\beta ( \tau ) =0.8\)

Example 4

Let us consider the arbitrary-order fractional differential equation of the form

Solution: We obtain the following FODEs based on the method that was introduced in Theorem 1:

hence

therefore

Integrating (5.45) by using formula (3.35), the parametric solution of (5.42) is

which leads to

Considering the initial condition \(f ( x ) = x^{2} +3x\), the solution u can be written as follows:

Remark 6

The classic case of Example 4, where \(\alpha ( \tau ) =\beta ( \tau ) =1\), is

and its solution is

its graph is given in Fig. 6.

The graph of the solution u in Example 4, where \(\alpha = \beta =1\)

The graph of u with another value for \(\alpha ( \tau )\) and \(\beta ( \tau )\) is given in Fig. 7.

The graph of the solution u in Example 4, where \(\alpha (\tau )=0.8\) and \(\beta (\tau )=0.6\). The graph (a) is the real part, and the graph (b) is the imaginary part of u

Example 5

Consider a bit more complicated case of the arbitrary-order fractional differential equation:

Solution: Based on Theorem 1 and comparing (5.51) with (4.1), we have

And from (4.4) we have

Therefore

where

Then, by integrating from (5.54)

implementing (3.36)

\(C_{1}\) and \(C_{2}\) are the integral arbitrary constants and

Then

The parametric solution for (5.51) is

Benchmark 3

(Example 5)

We show that (5.60) satisfies (5.51). We obtain the derivatives of the 1st equation in (5.60) regarding x with an order of \(\beta (\tau )\) and t with an order of \(\alpha ( \tau )\). Therefore, we have

hence

where \(f' ( \xi ) = f_{\xi } ' (\xi )\). Then the derivatives of the 2nd equation in (5.60), considering x with an order of \(\beta (\tau )\) and t with an order of \(\alpha ( \tau )\), are

hence, we have

Since the terms \(\xi _{x}^{ [ \beta ( \tau ) ]}\) and \(\xi _{t}^{ [ \alpha ( \tau ) ]}\) in (5.62) and (5.64) are common, we eliminate them, and we have

Substituting (5.65) in (5.51), we obtain

Therefore, (5.51) is satisfied if \(( -\psi +2 \beta ( \tau ) ) \xi ^{-\psi +2 \beta ( \tau ) -1} \neq 0\). Solution (5.60) satisfies the initial condition and is unique. (It can be easily verified similar to Benchmark 1.)

Remark 7

The graph of the solution u in Example 5 with different values of \(\alpha ( \tau )\) and \(\beta ( \tau )\) is given in Fig. 8.

(a), (c), (e) and (b), (d), (f) are respectively the graphs of the real and the imaginary parts of the solution u in Example 5 for different values of \(\alpha ( \tau )\) and \(\beta ( \tau )\)

6 Summary

We have proved the existence and uniqueness of the arbitrary-order fractional hyperbolic nonlinear scalar conservation law in time and space under certain conditions. We have used the generalization of the classical characteristic method and the generalization of some formulae from the constant-order fractional to the arbitrary-order fractional. And finally, we presented a few physical examples in which we have implemented the analytical technique that was introduced in Theorem 1 to find the solutions, and then we showed the graphs for different values of \(\alpha ( \tau )\) and \(\beta ( \tau )\). In the last example that is more complicated, and 1st and 2nd examples as a benchmark, we showed that the solution satisfies the differential equation. This benchmark can be performed for other cases too.

Abbreviations

- AOF:

-

Arbitrary-Order Fractional

- CM:

-

Characteristic Method

- FDEs:

-

Fractional Differential Equations

- FODEs:

-

Fractional Ordinary Differential Equations

- FPDEs:

-

Fractional Partial Differential Equations

- ODEs:

-

Ordinary Differential Equations

- PDEs:

-

Partial Differential Equations

- VOFC:

-

Variable-Order Fractional Calculus

- TSFDEs:

-

Time and Spatial Fractional Differential Equations

- VOF:

-

Variable-order Fractional

- HNSCL:

-

Hyperbolic Nonlinear Scalar Conservation Law

References

Jumarie, G.: Table of some basic fractional calculus formulae derived from a modified Riemann–Liouville derivative for non-differentiable functions. Appl. Math. Lett. 22, 378–385 (2009)

Jumarie, G.: On the representation of fractional Brownian motion as an integral with respect to \((\mathrm{d}t)^{a}\). Appl. Math. Lett. 18, 739–748 (2005)

Luchko, Y., Yamamoto, M.: General time-fractional diffusion equation: some uniqueness and existence results for the initial-boundary-value problems. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 19, 676–695 (2016)

Meerschaert, M.M., Zhang, Y., Baeumer, B.: Particle tracking for fractional diffusion with two time scales. Comput. Math. Appl. 59, 1078–1086 (2010)

Baleanu, D., Agrawal, O.P., Muslih, S.I.: Lagrangians with linear velocities within Hilfer fractional derivative. In: Proceedings of the ASME Design Engineering Technical Conference, vol. 3, pp. 335–338 (2011)

Metzler, R., Klafter, J.: The random walk’s guide to anomalous diffusion: a fractional dynamics approach. Phys. Rep. 339, 1–77 (2000)

Metzler, R., Klafter, J.: Boundary value problems for fractional diffusion equations. Phys. A, Stat. Mech. Appl. 278, 107–125 (2000)

Podlubny, I.: Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications. Academic Press, San Diego (1999)

Baleanu, D., Asad, J.H., Jajarmi, A.: New aspects of the motion of a particle in a circular cavity. Proc. Rom. Acad., Ser. A: Math. Phys. Tech. Sci. Inf. Sci. 19, 143–149 (2018)

Jajarmi, A., Ghanbari, B., Baleanu, D.: A new and efficient numerical method for the fractional modeling and optimal control of diabetes and tuberculosis co-existence. Chaos 29, 093111 (2019)

Baleanu, D., Shiri, B., Srivastava, H.M., Al Qurashi, M.: A Chebyshev spectral method based on operational matrix for fractional differential equations involving non-singular Mittag-Leffler kernel. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 353 (2018)

Baleanu, D., Jajarmi, A., Sajjadi, S.S., Mozyrska, D.: A new fractional model and optimal control of a tumor-immune surveillance with non-singular derivative operator. Chaos 29, 083127 (2019)

Baleanu, D., Shiri, B.: Collocation methods for fractional differential equations involving non-singular kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals 116, 136–145 (2018)

Jajarmi, A., Arshad, S., Baleanu, D.: A new fractional modelling and control strategy for the outbreak of dengue fever. Phys. A, Stat. Mech. Appl. 535, 122524 (2019)

Shiri, B., Baleanu, D.: System of fractional differential algebraic equations with applications. Chaos Solitons Fractals 120, 203–212 (2019)

Zhang, Z.Q., Wei, T.: Identifying an unknown source in time-fractional diffusion equation by a truncation method. Appl. Math. Comput. 219, 5972–5983 (2013)

Rostamy, D., Alipour, M., Jafari, H., Baleanu, D.: Solving multi-term orders fractional differential equations by operational matrices of BPs with convergence analysis. Rom. Rep. Phys. 65(2), 334–349 (2013)

Rostamy, D., Karimi, K.: Bernstein polynomials for solving fractional heat- and wave-like equations. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 15, 556–571 (2012)

Shi, P., Shillor, M.: On design of contact patterns in one dimensional thermoelasticity. In: Theoretical Aspects of Industrial Design, pp. 76–82 (1992)

Sokolov, I.M., Klafter, J.: From diffusion to anomalous diffusion: a century after Einstein’s Brownian motion. Chaos 15, 026103 (2005)

Zheng, G.H., Wei, T.: Spectral regularization method for a Cauchy problem of the time fractional advection–dispersion equation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 233, 2631–2640 (2010)

Zheng, G.H., Wei, T.: A new regularization method for a Cauchy problem of the time fractional diffusion equation. Adv. Comput. Math. 36, 377–398 (2012)

Samko, S.G., Ross, B.: Integration and differentiation to a variable fractional order. Integral Transforms Spec. Funct. 1, 277–300 (1993)

Ross, B., Samko, S.: Fractional integration operator of variable order in the Hölder spaces \(H^{\lambda (x)}\). Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 18, 777–788 (1995)

Chechkin, A.V., Gorenflo, R., Sokolov, I.M.: Fractional diffusion in inhomogeneous media. J. Phys. A, Math. Gen. 38, L679–L684 (2005)

Sun, H.G., Chen, W., Chen, Y.Q.: Variable-order fractional differential operators in anomalous diffusion modeling. Phys. A, Stat. Mech. Appl. 388, 4586–4592 (2009)

Wu, G.C., Deng, Z.G., Baleanu, D., Zeng, D.Q.: New variable-order fractional chaotic systems for fast image encryption. Chaos 29, 083103 (2019)

Tavares, D., Almeida, R., Torres, D.F.M.: Caputo derivatives of fractional variable order: numerical approximations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 35, 69–87 (2016)

Shiri, B., Baleanu, D.: Numerical solution of some fractional dynamical systems in medicine involving non-singular kernel with vector order. Results Nonlinear Anal. 2, 160–168 (2019)

Myint-U, T., Debnath, L.: Linear Partial Differential Equations for Scientists and Engineers (2007)

Wu, G.C.: A fractional characteristic method for solving fractional partial differential equations. Appl. Math. Lett. 24, 1046–1050 (2011)

Jumarie, G.: Modified Riemann–Liouville derivative and fractional Taylor series of nondifferentiable functions further results. Comput. Math. Appl. 51, 1367–1376 (2006)

Jumarie, G.: On the derivative chain-rules in fractional calculus via fractional difference and their application to systems modelling. Open Phys. 11, 617–633 (2013)

Acknowledgements

Reza Shirkhorshidi would like to express his sincere gratitude and appreciation to Fatemeh Zahedifar, who helped in editing and preparing the paper, and also Seyed Ali Shirkhorshidi, who helped in dealing with technical problems that were encountered in the process of developing this article.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The University Malaya grant GF033-2018 partially supports this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SMRS: He has formed and developed the idea of the paper; also, he has typed the paper. He interconnected with all the authors to collect their suggestions and editions and imposed those in the article. Professor Dr. DR: He had helped the formation of the main idea, revised and edited the article every step of the way until its final form. Associate Professor Dr. WAMO: She had improved the paper and guided in every step of the way throughout the article. Also, she had done quite a bit of editing and revising too. Mr. MAOA: He had spent quite a bit of time discussing different subjects and problems related to this paper, which caused the paper’s improvement; he also read, revised, and corrected the content of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shirkhorshidi, S.M.R., Rostamy, D., Othman, W.A.M. et al. The arbitrary-order fractional hyperbolic nonlinear scalar conservation law. Adv Differ Equ 2020, 253 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02697-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02697-8