Abstract

In this paper, we study the asymptotic behavior of the solutions of a new class of difference equations

where l and k are nonnegative integers, a and b are nonnegative real numbers, the initial values \(x_{-s}, x_{-s+1},\ldots, x_{0}\) are positive real numbers, \(s=\max\{l,k\}\), and \(f (u,v ): ( 0,\infty ) ^{2}\rightarrow ( 0,\infty ) \) is a continuous and homogeneous real function of degree zero. We consider the stability, boundedness, and periodicity of the solutions of this equation which is the most general form of linear difference equations. Thus, the results in this paper apply to several other equations that are special cases of the studied equation. Moreover, we present a new method to study periodic solutions of period two.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Difference equations describe the observed evolution of a phenomenon at discrete time steps. Thus, difference equations are used as discrete models of the workings of physical or artificial systems. The asymptotic behavior of the solutions of linear difference equations is a qualitative property having important applications in many areas, including control theory, mathematical biology, neural networks, and so forth. We cannot use numerical methods to study the asymptotic behavior of all solutions of a given equation due to the global nature of that behavior. Therefore, the analytical study of those qualitative properties has been attracting considerable interest from mathematicians and engineers, as the only method to gain insight into those properties.

This paper is concerned with the study of the asymptotic behavior of the solutions of a general class of difference equations

where l and k are nonnegative integers, a and b are nonnegative real numbers, and \(f (u,v ): ( 0,\infty ) ^{2}\rightarrow ( 0,\infty ) \) is a continuous and homogeneous real function of degree zero. The construction of this new class of difference equations is complex and involves several cases. For example, one can assume \(a = 0\) or \(b = 0\) or both. That makes our analysis better suited for studying those equations. For studies on equations of a similar form, the reader is referred to [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. We begin our study with a review of the background on equations having a similar form to the one we consider in this paper.

Kalabušić and Kulenović [15] and Kulenović and Ladas [18] studied the difference equation

Elsayed [12] investigated the asymptotic behavior of the difference equation

Zayed and El-Moneam [26, 27, 29] studied the asymptotic behavior of the difference equation

whereas Zayed and El-Moneam [28] studied the global and asymptotic properties of the solutions of the difference equation

Notice that these equations as well as several other equations not listed above are special cases of equation (1.1).

The results in this paper make three main contributions to the study of linear difference equations. First, we formulate a general class of difference equations as a means of establishing general theorems for the asymptotic behavior of its solutions and the solutions of equations that are special cases of the studied equation. Second, we study the asymptotic behavior of the solutions of this more general class of difference equations using an efficient method introduced in [12] and modified in [19]. Theorem 3.2 establishes how this method can be applied to equation (1.1). In particular, this method is also valid and can be applied to several classes of difference equations for which the classical method fails to give results. Moreover, we consider difference equations with real coefficients and initial values which extend and slightly improve previous results. Third, we can use our analysis to check and verify the results obtained by other researchers.

For the basic definitions and auxiliary lemmas we use for establishing our results, namely equilibrium points, local stability, and periodicity of the solutions, we refer the reader to [1, 9, 17, 18]. For the convenience of the reader, we present below some related results.

Lemma 1.1

(see [17, Theorem 1.3.7])

Assume that \(p,q\in \mathbb{R} \) and \(k\in \{ 0,1,2,\ldots \} \). Then \(\vert p \vert + \vert q \vert <1\) is a sufficient condition for the asymptotic stability of the difference equation

Lemma 1.2

(see [9, Corollary 4])

Let \(f:\mathbb{R} _{+}^{n}\rightarrow \mathbb{R} \) be continuous and differentiable on \(\mathbb{R} _{++}^{n}\). If f is homogeneous of degree k, then \(D_{j}f=\partial f/\partial x_{j}\) is homogeneous of degree \(k-1\).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we study the stability behavior and boundedness of the solutions of equation (1.1) and give an illustrative example in support of our analysis. In Sect. 3, we present a technique to investigate the periodic behavior of the solutions of equation (1.1). A distinguishing feature of our criteria is that the coefficients l and k of equation (1.1) can be odd or even. Two examples are provided to illustrate the new method for studying periodic solutions. In Sect. 4, the practicability, maneuverability, and efficiency of the results obtained are illustrated via two applications.

2 Dynamics of equation (1.1)

2.1 Local stability

Here, we investigate the local stability of the equilibrium point of equation (1.1), which is given by

Hence, the positive equilibrium point is

Now, we define the function \(\phi ( u,v ): ( 0,\infty ) ^{2}\rightarrow ( 0,\infty ) \) by

so that

Theorem 2.1

The equilibrium point of equation (1.1) \(\overline {x}= ( 1-a-b ) ^{-1}f ( 1,1 ) \) is locally asymptotically stable if

where

Proof

The linearized equation of equation (1.1) about x̅ is the linear difference equation

Hence, by Lemma 1.1, equation (1.1) is locally stable if

Therefore,

From Euler’s homogeneous function theorem, we deduce that \(uf_{u}=-vf_{v}\) and thus \(f_{u}f_{v}<0\). If \(f_{u}>0\), then

Using Lemma 1.2, we get

which implies that inequality (2.1) is equivalent to

and so

Next, if \(f_{u}<0\), then

Similarly, we find

which completes the proof. □

Example 2.1

Consider the difference equation

where c is a positive real number. Note that \(f ( u,v ) =c u/v\). By Theorem 2.1, the equilibrium point of equation (2.2) \(\overline{x}=c/(1-a-b)\) is locally asymptotically stable if

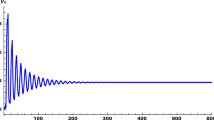

For example, for \(l=0\), \(k=1\), \(a=0.2\), \(b=0.3\), \(c=1\), \(x_{-1}=2.8\), and \(x_{0}=1.5\), the stable solution of (2.2) is shown in Fig. 1.

Stable solution corresponding to difference equation (2.2)

2.2 Boundedness

In this section, we study the boundedness of the solutions of equation (1.1).

Theorem 2.2

If \(a+b < 1\) and there exists a positive constant L such that \(f ( u,v ) < L\) for all \(u,v\in ( 0,\infty )\), then every solution of equation (1.1) is bounded.

Proof

From equation (1.1), we obtain

Using a comparison, we can write the right-hand side as follows:

and this equation is locally stable if \(a+b<1\) and converges to the equilibrium point \(\overline{y}=L/ ( 1-a-b ) \). Then we have \(x_{n}< y_{n}\) and

Thus, every solution of (1.1) is bounded. □

Remark 2.3

As fairly noticed by the referees, the global asymptotic stability of equation (1.1) remains an open problem for further research.

3 Periodic solutions

Theorem 3.1

If l and k are either odd or even, then equation (1.1) has no solutions of prime period two.

Proof

Suppose that l and k are even and equation (1.1) has a prime period two solution

Then \(x_{n-l}=x_{n-k}=q\). From equation (1.1), we have

Thus, we get

which is a contradiction. Another case can be shown similarly. This completes the proof. □

Theorem 3.2

Assume that l is odd and k is even. Then equation (1.1) has a prime period two solution

if and only if

where \(\tau=p/q\).

Proof

Without loss of generality, we can assume that \(l>k\). Now, let equation (1.1) have a prime period two solution

Since l is odd and k is even, we arrive at \(x_{n-l}=p\) and \(x_{n-k}=q\). From equation (1.1), we get

This yields

where \(\tau=p/q\). Then we obtain

Since \(p=\tau q\), we find

On the other hand, suppose that (3.1) is satisfied. Now, we choose

where

and \(\tau\in \mathbb{R} ^{+}\). Hence, we see that

From (3.1), we have

and so

which together with (3.2) implies that

Similarly, we can show that \(x_{2}=\lambda f ( \tau,1 ) +\mu f ( 1,\tau ) \). Then, by induction, we conclude that

This completes the proof. □

Theorem 3.3

Assume that l is even and k is odd. Then equation (1.1) has a prime period two solution

if and only if

where \(\tau=p/q\).

Proof

The proof is similar to that of Theorem 3.2 and thus is omitted. □

Example 3.1

Consider equation (2.2) and assume that l is odd and k is even. By virtue of Theorem 3.2, equation (2.2) has a prime period two solution

if and only if

Since \(\tau\neq1\), we obtain

Letting

we get \(a+3b<1\). For a numerical example, we take \(l=1\), \(k=0\), \(a=0.3\), \(b=0.2\), \(c=1\), \(x_{-1}=3.3333\), and \(x_{0}=1.6667\); see Fig. 2.

Prime period two solution of equation (2.2)

Remark 3.4

Consider the equation

which was studied by Zayed and El-Moneam [28]. Define the function

Then f is homogeneous with degree zero and

From Theorem 2.1, the positive equilibrium point of equation (3.4) is

This point is asymptotically stable if \(p>q\) and

Since \(1-a-b>0\), we obtain the condition

Also, if \(q>p\), then we have the condition

(Results of Theorem 6 in [28]). From Theorem 3.1, if k is even, then equation (3.4) has no prime period two solutions. Furthermore, using Theorem 3.3, if k is odd, then equation (3.4) has a prime period two solution if and only if

and so

Since \(\tau\neq1\), we have

Thus,

We note that if \(p,q>1\) or \(p,q<1\), then equation (3.4) has no prime period two solutions.

Remark 3.5

Several equations that have been studied in [26, 27, 29] can be treated as special cases of (1.1).

4 Applications

Here, two test cases are given to validate the asymptotic behavior of the proposed new class of difference equations.

4.1 Application 1

Consider the difference equation

where \(\beta\geq2\) is a positive integer and \(c_{i}\) are positive real numbers for all \(i=0,1,\ldots,\beta\). Now, we define the functions

and

where f is homogeneous with degree zero and

Note that \(f_{u}>0\). Then, by Theorem 2.1, the positive equilibrium point

of equation (4.1) is locally asymptotically stable if

For a numerical example, we take \(l=0\), \(k=1\), \(\beta=3\), \(c_{0}=2\), \(c_{1}=0.2\), \(c_{2}=0.2\), \(c_{3}=0.1\), \(x_{-1}=5.5\), and \(x_{0}=4.5\); see Fig. 3.

Stable solution of difference equation (4.1)

Assume that l is odd and k is even. It follows from Theorem 3.2 that equation (4.1) has a prime period two solution \(\ldots,p,q,p,q,\ldots\) if and only if

If \(a\neq1\), then

Now, we have

Then, we get \(\sum_{i=1}^{\beta} ( 2i-1 ) c_{i}< c_{0}\). For a numerical example, we take \(l=1\), \(k=0\), \(\beta=2\), \(a=0.1\), \(c_{0}=19/3\), \(c_{1}=2\), \(c_{2}=1\), \(x_{-1}=23.704\), and \(x_{0}=7.9012\); see Fig. 4.

Prime period solution of equation (4.1)

Conjecture 1

Note that, if \(\sum_{i=1}^{\beta} ( 2i-1 ) c_{i}< c_{0}\), then every solution of equation (4.1) converges either to the equilibrium point or to a periodic solution having period two.

4.2 Application 2

Consider the difference equation

where c is a real number. For \(c>0\), define the function

which is homogeneous with degree zero and

By Theorem 2.1, the positive equilibrium point of equation (4.2)

is locally asymptotically stable if

Then

or

For a numerical example, we take \(l=0\), \(k=1\), \(a=0.8\), \(b=0.1\), \(c=1\), \(x_{-1}=5\), and \(x_{0}=5.9\); see Fig. 5. Taking into account that \(0< f ( u,v ) <1\), an application of Theorem 2.2 implies that every solution of equation (4.2) is bounded in this case.

Stable solution of difference equation (4.2)

Let l be odd and k be even. By Theorem 3.2, equation (4.2) has a prime period two solution \(\ldots,p,q,p,q,\ldots\) if and only if

that is,

For a numerical example, we take \(l=1\), \(k=0\), \(a=0.2\), \(b=0.3\), \(c=-1.2479\), \(x_{-1}=18.663\), and \(x_{0}=9.3316\); see Fig. 6.

Prime period solution of equation (4.2)

References

Abdelrahman, M.A.E., Moaaz, O.: Investigation of the new class of the nonlinear rational difference equations. Fundam. Res. Dev. Int. 7(1), 59–72 (2017)

Abo-Zeid, R.: Attractivity of two nonlinear third order difference equations. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 21(3), 241–247 (2013)

Abo-Zeid, R.: On the oscillation of a third order rational difference equation. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 23(1), 62–66 (2015)

Abu-Saris, R.M., DeVault, R.: Global stability of \(y_{n+1}=A + \frac{y_{n}}{y_{n-k}}\). Appl. Math. Lett. 16(2), 173–178 (2003)

Amleh, A.M., Grove, E.A., Ladas, G., Georgiou, D.A.: On the recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=\alpha+x_{n-1}/x_{n}\). J. Math. Anal. Appl. 233(2), 790–798 (1999)

Berenhaut, K.S., Foley, J.D., Stević, S.: The global attractivity of the rational difference equation \(y_{n}=1 +\frac{y_{n-k}}{y_{n-m}}\). Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 135(4), 1133–1140 (2007)

Berenhaut, K.S., Stević, S.: A note on positive non-oscillatory solutions of the difference equation \(x_{n+1}=\alpha+\frac{x_{n-k}^{p}}{x_{n}^{p}}\). J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 12(5), 495–499 (2006)

Berenhaut, K.S., Stević, S.: The behaviour of the positive solutions of the difference equation \(x_{n}=A + (\frac{x_{n-2}}{x_{n-1}} )^{p}\). J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 12(9), 909–918 (2006)

Border, K.C.: Euler’s theorem for homogeneous functions (2000) http://www.its.caltech.edu/~kcborder/Notes/EulerHomogeneity.pdf

DeVault, R., Kent, C., Kosmala, W.: On the recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}= p + \frac{x_{n-k}}{x_{n}}\). J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 9(8), 721–730 (2003)

DeVault, R., Ladas, G., Schultz, S.W.: On the recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=\frac{A}{x_{n}}+ \frac {1}{x_{n-2}}\). Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 126(11), 3257–3261 (1998)

Elsayed, E.M.: New method to obtain periodic solutions of period two and three of a rational difference equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 79(1), 241–250 (2015)

Grove, E.A., Ladas, G.: Periodicities in Nonlinear Difference Equations, vol. 4. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton (2005)

Hamza, A.E.: On the recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=\alpha+{x_{n-1}}/{x_{n}}\). J. Math. Anal. Appl. 322(2), 668–674 (2006)

Kalabušić, S., Kulenović, M.R.S.: On the recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}= \frac{\gamma x_{n-1}+\delta x_{n-2}}{C x_{n-1}+D x_{n-2}}\). J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 9(8), 701–720 (2003)

Khuong, V.V.: On the positive nonoscillatory solution of the difference equations \(x_{n+1}=\alpha+ (x_{n-k}/x_{n-m} )^{p}\). Appl. Math. J. Chin. Univ. Ser. B 24, 45–48 (2009)

Kocic, V.L., Ladas, G.: Global Behavior of Nonlinear Difference Equations of Higher Order with Applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht (1993)

Kulenović, M.R.S., Ladas, G.: Dynamics of Second Order Rational Difference Equations with Open Problems and Conjectures. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton (2002)

Moaaz, O.: Comment on “New method to obtain periodic solutions of period two and three of a rational difference equation” [Nonlinear Dyn. 79: 241–250]. Nonlinear Dyn. 88(2), 1043–1049 (2017)

Moaaz, O., Abdelrahman, M.A.E.: Behaviour of the new class of the rational difference equations. Electron. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 4(2), 129–138 (2016)

Öcalan, Ö.: Dynamics of the difference equation \(x_{n+1}=p_{n}+\frac {x_{n-k}}{x_{n}}\) with a period-two coefficient. Appl. Math. Comput. 228, 31–37 (2014)

Saleh, M., Aloqeili, M.: On the rational difference equation \(y_{n+1}=A+\frac {y_{n-k}}{y_{n}}\). Appl. Math. Comput. 171(2), 862–869 (2005)

Stević, S.: On the recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=\alpha+\frac {x_{n-1}^{p}}{x_{n}^{p}}\). J. Appl. Math. Comput. 18(1–2), 229–234 (2005)

Sun, T., Xi, H.: On convergence of the solutions of the difference equation \(x_{n+1}=1+ \frac{x_{n-1}}{x_{n}}\). J. Math. Anal. Appl. 325(2), 1491–1494 (2007)

Yan, X.-X., Li, W.-T., Zhao, Z.: On the recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=\alpha- (x_{n}/x_{n-1})\). J. Appl. Math. Comput. 17(1–2), 269–282 (2005)

Zayed, E.M.E., El-Moneam, M.A.: On the rational recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=Ax_{n}+ {(\beta x_{n}+\gamma x_{n-k})}/{(Cx_{n}+Dx_{n-k})}\). Commun. Appl. Nonlinear Anal. 16(3), 91–106 (2009)

Zayed, E.M.E., El-Moneam, M.A.: On the rational recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=\gamma x_{n-k}+ {(a x_{n}+b x_{n-k})}/{(cx_{n}-dx_{n-k})}\). Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 36(1), 103–115 (2010)

Zayed, E.M.E., El-Moneam, M.A.: On the rational recursive sequence \(x_{n+1}=Ax_{n} + B x_{n-k}+\frac{\beta x_{n}+\gamma x_{n-k}}{Cx_{n}+Dx_{n-k}}\). Acta Appl. Math. 111(3), 287–301 (2010)

Zayed, E.M.E., El-Moneam, M.A.: On the rational recursive two sequences \(x_{n+1}= a x_{n-k}+ {b x_{n-k}}/{(cx_{n}+\delta d x_{n-k})}\). Acta Math. Vietnam. 35(3), 355–369 (2010)

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the editors and two anonymous referees for the careful reading of the original manuscript and useful comments that helped to improve the presentation of the results and accentuate important details.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Funding

This research is supported by NNSF of P.R. China (Grant No. 61503171), CPSF (Grant No. 2015M582091), NSF of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2016JL021), KRDP of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2017CXGC0701), DSRF of Linyi University (Grant No. LYDX2015BS001), and the AMEP of Linyi University, P.R. China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All four authors contributed equally to this work. They all read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelrahman, M.A.E., Chatzarakis, G.E., Li, T. et al. On the difference equation \(x_{n+1}=ax_{n-l}+bx_{n-k}+f ( x_{n-l},x_{n-k} )\). Adv Differ Equ 2018, 431 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1880-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1880-8