Abstract

In this paper, we consider the bifurcation curves and exact multiplicity of positive solutions of the one-dimensional Minkowski-curvature equation

where λ and L are positive parameters, \(f\in C[0,\infty ) \cap C^{2}(0,\infty )\), and \(f(u)>0\) for \(0< u< L\). We give the precise description of the structure of the bifurcation curves and obtain the exact number of positive solutions of the above problem when f satisfies \(f''(u)>0\) and \(uf'(u)\geq f(u)+\frac{1}{2}u^{2}f''(u)\) for \(0< u< L\). In two different cases, we obtain that the above problem has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to different ranges of λ. The arguments are based upon a detailed analysis of the time map.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In this work, we study the bifurcation curves and exact multiplicity of positive solutions of the quasilinear two-point boundary value problem

where λ and L are positive parameters, \(f\in C[0,\infty ) \cap C^{2}(0,\infty )\), and \(f(u)>0\) for \(0< u< L\). As is known, problem (1.1) is one-dimensional version of the Minkowski-curvature equation with Dirichlet boundary value condition

which plays a role in differential geometry and in the theory of relativity.

Recently, both (1.1) and (1.2), or even more general problems, have been widely investigated in order to assure the existence, as well as the multiplicity, of solutions (see, e.g., [1–7, 10, 11] and the references therein). In [3], the existence and multiplicity of positive solutions for the one-dimensional Minkowski-curvature equation

have been proved under the assumption that f is an \(L^{p}\)-Carathéodory function by using variational or topological methods; here f is not required to be positive. Furthermore, Coelho et al. [4] proved the existence and multiplicity of positive radial solutions of the Dirichlet problem for the Minkowski-curvature equation in a ball.

Bereanu et al. [1] proved the existence of classical positive radial solutions of (1.2) by employing Leray–Schauder degree arguments, critical point theory, and lower semicontinuous perturbations of \(C^{1}\)-functionals, where \(\Omega =\{x\in \mathbb{R}^{N} |\, |x|< R \}\), \(f\in C([0,R]\times [0,\alpha ), \mathbb{R})\), \(0<\alpha \leq \infty \), and \(f(r,s)>0\), \((r,s)\in [0,R]\times [0,\alpha )\). In particular, if \(f(|x|,u)=\mu (|x|)u^{p}\), \(p>1\) and \(\mu :[0,\infty )\to \mathbb{R}\) is continuous, strictly positive on \((0,\infty )\), Bereanu et al. [2] obtained that there exists \(\Lambda >0\) such that problem (1.2) has zero, at least one, or at least two positive radial solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\Lambda )\), \(\lambda =\Lambda \), or \(\lambda >\Lambda \). The proof of this result is based on the method of lower and upper solutions and Leray–Schauder degree arguments. By applying the unilateral global bifurcation theory and some preliminary results on the superior limit of a sequence of connected components, Ma et al. [11] and Dai [5] proved the existence, nonexistence, and multiplicity of radial positive solution of problem (1.2) corresponding to asymptotically linear, sublinear, and superlinear nonlinearities f at zero, respectively, which generalized and improved the results in the literature [1, 2].

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the above references mainly studied the existence but not the exactness of positive solutions. Recently, the exact number of the positive solutions have been considered by Zhang and Feng [12] and Huang [8, 9]. In [12], the authors obtained the main results as follows:

Theorem A

Assume that f satisfies the following conditions:

(1) \(f\in C([0,\infty ), \mathbb{R})\) and \(f(u)>0\) for every \(u>0\);

(2) \(f\in C^{1}([0,\infty ), \mathbb{R})\) and \(f'(u)u\leq f(u)\) for every \(u>0\).

Then

(a) If \(f(0)>0\) or \(f(0)=0\) and there exists \(0<\beta <1\) such that \(0<\lim_{r\to 0}\frac{f(r)}{r^{\beta }}=A<+\infty \), then, for any \(\lambda >0\), problem (1.1) has exactly one positive solution.

(b) If \(f(0)=0\) and \(0<\lim_{r\to 0}\frac{f(r)}{r}=A<+\infty \), then, for any \(\lambda >\frac{\pi ^{2}}{4L^{2} A}\), problem (1.1) has exactly one positive solution.

Theorem B

Assume that \(f(u)=u^{p}\ (p>1)\). Then there exists \(\lambda ^{*}>0\) such that problem (1.1) has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\lambda ^{*})\), \(\lambda =\lambda ^{*}\), or \(\lambda >\lambda ^{*}\).

Huang [8] discussed the exact number of positive solutions of problem (1.1), where \(f\in C[0,\infty )\cap C^{2}(0,\infty )\), \(f(u)>0\) for \(u>0\), and \(f''(u)\) is not sign-changing on \((0,\infty )\). Assume the following condition holds:

(H) For any \(\lambda ,\alpha >0\), there exists \(\rho =\rho (\alpha ,\lambda )\in \mathbb{R}\) such that, for \(0< u<\alpha \),

where \(A=A(u,\alpha )\equiv \alpha f(\alpha )-uf(u)\), \(B=B(u,\alpha )\equiv F( \alpha )-F(u)\), \(C=C(u,\alpha )\equiv \alpha ^{2} f'(\alpha )-u^{2}f'(u)\). When \(f''(u)\leq 0\), the bifurcation curve of (1.1) is monotone increasing. However, it is a complicated situation for \(f''(u)>0\). Obviously, condition (H) can ensure \(T''_{\lambda }(\alpha )+\frac{\rho (\alpha ,\lambda )}{\alpha }T'_{ \lambda }(\alpha )>0\) but the exact value of \(\rho (\alpha ,\lambda )\) is unknown and difficult to get in calculation. Moreover, in [9], Huang obtained the classification and evolution of bifurcation curves of (1.1) under certain assumptions. We hope to give more direct conditions to judge the graph of bifurcation curves.

Therefore, in this paper, we study the bifurcation curves and exact multiplicity of positive solutions of problem (1.1), where the nonlinearity f satisfies

(H1) \(f\in C([0,\infty ),\mathbb{R})\) and \(f(u)>0\) for \(0< u< L\);

(H2) \(f\in C^{2}((0,\infty ),\mathbb{R})\), \(f''(u)>0\), and \(uf'(u)\geq f(u)+\frac{1}{2}u^{2}f''(u)\) for \(0< u< L\).

We consider the following two cases:

(C1) \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r^{\beta }}=A\in (0,+ \infty )\), \(\beta >1\);

(C2) \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r}=A\in (0,+\infty )\) and \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}f''(u)\in (0,\infty ]\).

Our main results are as follows:

Theorem 1.1

Assume f satisfies (H1), (H2), and (C1). Then there exists \(\lambda _{*}>0\) such that

(i) For \(0<\lambda <\lambda _{*}\), problem (1.1) has no positive solution;

(ii) For \(\lambda =\lambda _{*}\), problem (1.1) has exactly one positive solution;

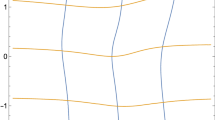

(iii) For \(\lambda >\lambda _{*}\), problem (1.1) has exactly two positive solutions (see Fig. 1(a)).

Theorem 1.2

Assume f satisfies (H1), (H2), and (C2). Then there exists \(0<\lambda _{*}<\lambda ^{*}=\frac{\pi ^{2}}{4L^{2}A}\) such that

(i) For \(0<\lambda <\lambda _{*}\), problem (1.1) has no positive solution;

(ii) For \(\lambda =\lambda _{*}\) and \(\lambda \geq \lambda ^{*}\), problem (1.1) has exactly one positive solution;

(iii) For \(\lambda _{*}<\lambda <\lambda ^{*}\), problem (1.1) has exactly two positive solutions (see Fig. 1(b)).

Remark 1.1

Since condition (H2) implies \(uf'(u)>f(u)\), Theorems 1.1 and 1.2 are new results which are completely different from Theorem A. However, on account of the restriction of condition (H2), our results do not include the case of \(f(u)=u^{p}\) (\(p>2\)).

Remark 1.2

Compared with [8], it is easy to obtain \(T_{\lambda }''(r)>0\) when the nonlinearity f satisfies (H1) and (H2), but the condition (H2) is stronger than the hypothetical condition (H).

Remark 1.3

It follows from \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r^{\beta }}=A\in (0,+\infty )\), \(0< \beta <1\), that \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r}=+\infty \). However, (H2) implies that \(\frac{f(u)}{u}\) is monotonically increasing on \((0,L)\). Therefore, \(\beta \geq 1\) if (H2) holds.

Remark 1.4

If \(f\in C^{3}((0,\infty ),\mathbb{R})\), then \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r}=A\in (0,+\infty )\), \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}f''(u)=0\), and condition (H2) imply that \(f'''(r)\leq 0\) for small positive numbers r. However, for small positive numbers r, it is easy to obtain that \(f''(r)\leq 0\) from \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}f''(u)=0\) and \(f'''(r)\leq 0\), which is a contradiction with \(f''(u)>0\) for \(0< u< L\). Therefore, the case of \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r}=A\in (0,+\infty )\) and \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}f''(u)=0\) may not occur if f satisfies (H2).

We organized the paper as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce and give some properties of the time map. Section 3 is devoted to proving the main results. Section 4 contains some examples.

2 Time map

In this section, we shall make a detailed analysis of time maps for the one-dimensional Minkowski-curvature equation (1.1) and give some properties.

Let \(u(x)\) be a solution of problem (1.1). It is well known that \(u(x)\) takes its maximum at \(x=0\), \(u(x)\) is symmetric with respect to 0, \(u'(x)>0\) for \(-L\leq x<0\), and \(u'(x)<0\) for \(0< x\leq L\). Therefore, problem (1.1) is equivalent to the following problem:

Let \(v=\frac{u'}{\sqrt{1-u^{\prime \,2}}}\), \(u(0)=r\), then \((u,v)\) is a solution of the following problem defined on \([0,L]\):

Denote \(F(u)=\int _{0}^{u} f(s)\,ds\).

The function \(H(x)=1-\sqrt{1+v^{2}(x)}-\lambda F(u(x))\) satisfies

and \(H(0)=-\lambda F(r)\), hence we obtain

Therefore,

Then

Integrating (2.1) from 0 to L leads to

The function \(T_{\lambda }(r)\) is called the time map of f.

For the sake of simplicity [12], in what follows, we usually denote \(T_{\lambda }(r)\) by \(T(r)\), \(\frac{\partial T}{\partial r}\) by \(T'\), and \(\xi =\lambda (F(r)-F(rs))\), \(\xi '=\frac{\partial \xi }{\partial r}= \lambda (f(r)-sf(rs))\), \(\xi ''=\frac{\partial ^{2} \xi }{\partial r^{2}}=\lambda (f'(r)-s^{2}f'(rs))\), and then

Lemma 2.1

([12])

Assume \(f:{[0,+\infty )}\to [0,+ \infty )\) satisfies (H1), then the time map \(T(r)\) has continuous derivatives up to the second order with respect to r, and

Lemma 2.2

([12])

Assume that (H1) holds. Then for any \(r\in (0,L)\), the time map T is strictly decreasing with respect to λ.

Lemma 2.3

([12])

Assume (H1) holds.

(1) If \(f(0)>0\), then \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T(r)=0\).

(2) If \(f(0)=0\) and \(0<\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r^{\beta }}=A<+\infty \), then

(2a) If \(0<\beta <1\), then \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T(r)=0\);

(2b) If \(\beta =1\), then \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T(r)=\frac{\pi }{2\sqrt{\lambda A}}\);

(2c) If \(\beta >1\), then \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T(r)=+\infty \).

Lemma 2.4

([8])

Assume that \(\eta \equiv \lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{F(r)}{r^{2}}=\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{2r}\in (0,\infty )\), then for \(\lambda >0\),

Lemma 2.5

Assume (H1) holds and \(0<\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r^{\beta }}=A<+\infty \), then

(1) If \(0<\beta <1\), then \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T'(r)=+\infty \).

(2) If \(\beta >1\), then \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T'(r)=-\infty \).

Proof

Letting \(u=r\tau \), we get

Since \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r^{\beta }}=A \), it follows that

It is easy to see that \(T'(r)\) is continuous with respect to r by Lemma 2.1. Combining with (2.2) and (2.3), we obtain

It is easy to get

Therefore, \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}} T'(r)= +\infty \) as \(0<\beta <1\) and \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}} T'(r)= -\infty \) as \(\beta >1\). □

Lemma 2.6

Assume f satisfies (H1) and (H2), then, for any \(\lambda >0\),

Proof

By Lemma 2.1,

It is easy to get that \(r(\xi (2+\xi ))^{\frac{5}{2}}>0\). As \(1+\xi >\frac{2+\xi }{2}\), we obtain

Due to \(\xi =\lambda (F(r)-F(rs))\), \(\xi '=\lambda (f(r)-sf(rs))\), we have

Let \(G_{1}(r)=rf(r)-2F(r)\), then \(r\xi '-2\xi =\lambda [G_{1}(r)-G_{1}(rs)]\). It follows from (H2) that \(G_{1}'(r)=rf'(r)-f(r)>0\). Hence, for \(0< s<1\), we get

that is,

From (2.4) and (2.5), we obtain

In fact,

Let \(G_{2}(r)=4rf(r)-6F(r)-r^{2}f'(r)\), then \(4r\xi '-6\xi -r^{2}\xi ''=\lambda [G_{2}(r)-G_{2}(rs)]\). It follows from (H2) that \(G_{2}'(r)=2rf'(r)-2f(r)-r^{2}f''(r)\geq 0\), which implies that \(4r\xi '-6\xi -r^{2}\xi ''\geq 0\). Therefore, \(T''(r)>0\). □

3 Proof of the main results

Proof of Theorem 1.1

According to the definition of the time map, problem (1.1) is equivalent to finding \(r\in (0,L)\) such that

Therefore, the number of solutions of (1.1) is precisely the number of solutions of (3.1).

From Lemma 2.3 and Lemma 2.5, \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T(r)=+\infty \), \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T'(r)=-\infty \). By calculation, for a given \(r_{0}>0\),

which implies that there exists \(r_{0}\in (0,L)\) such that \(\lim_{\lambda \to +\infty }T(r_{0})< L\).

By Lemma 2.6, \(T(r)\) has exactly one critical point in the interval \(r\in (0,L)\) for \(\lambda \geq \lambda _{*}\). Thus, combining with Lemma 2.2, we have obtained a precise description of the graph of \(T(r)\) for \(\lambda \geq \lambda _{*}\), see Fig. 2.

Graph of \(T(r)\) in Theorem 1.1

There exists \(\lambda _{*}>0\) such that problem (1.1) has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\lambda _{*})\), \(\lambda =\lambda _{*}\), or \(\lambda \in (\lambda _{*},+\infty )\), respectively. □

Proof of Theorem 1.2

According to the definition of the time map, problem (1.1) is equivalent to finding \(r\in (0,L)\) such that

Therefore, the number of solutions of (1.1) is precisely the number of solutions of (3.2).

As \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r}=A\in (0,\infty )\), by Lemma 2.3, we know that \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T(r)=\frac{\pi }{2\sqrt{\lambda A}}\). From \(\frac{\pi }{2\sqrt{\lambda A}}=L\), \(\lambda =\frac{\pi ^{2}}{4L^{2}A}\triangleq \lambda ^{*}\). By calculation,

By Lemma 2.4, \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}T'(r)<0\). From Lemma 2.6, \(T(r)\) has exactly one critical point in the interval \(r\in (0,L)\) for \(\lambda \geq \lambda _{*}\). Therefore, combining with Lemma 2.2, we have obtained a precise description of the graph of \(T(r)\) for \(\lambda \geq \lambda _{*}\), see Fig. 3.

Graph of \(T(r)\) in Theorem 1.2

There exists \(0<\lambda _{*}<\lambda ^{*}=\frac{\pi ^{2}}{4L^{2}A}\) such that problem (1.1) has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\lambda _{*})\), \(\lambda = \lambda _{*}\), or \(\lambda \geq \lambda ^{*}\), \(\lambda \in (\lambda _{*},\lambda ^{*})\), respectively. □

4 Applications

Example 4.1

Consider \(f(u)=u\ln (1+u)\) for \(u>0\).

By calculation, \(f''(u)=\frac{2+u}{(1+u)^{2}}>0\), \(uf'(u)-f(u)-\frac{1}{2}u^{2}f''(u)=\frac{u^{3}}{2(1+u)^{2}}>0\) and \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r^{2}}=\lim_{r\to 0^{+}} \frac{rln(1+r)}{r^{2}}=1\), so f satisfies (H1), (H2), and (C1). Therefore, by Theorem 1.1, there exists \(\lambda _{*}>0\) such that problem (1.1) has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\lambda _{*})\), \(\lambda =\lambda _{*}\), \(\lambda \in (\lambda _{*},+\infty )\), respectively.

Example 4.2

Consider \(f(u)=u^{p}\ (1< p\leq 2)\) for \(u>0\).

By calculation, \(f''(u)=p(p-1)u^{p-2}>0\), \(uf'(u)-f(u)-\frac{1}{2}u^{2}f''(u)=\frac{1}{2}u^{p}(p-1)(2-p)\geq 0\) and \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r^{\beta }}=\lim_{r \to 0^{+}}\frac{r^{p}}{r^{\beta }}=1\), \((1<\beta =p\leq 2)\), so f satisfies (H1), (H2), and (C1). Therefore, by Theorem 1.1, there exists \(\lambda _{*}>0\) such that problem (1.1) has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\lambda _{*})\), \(\lambda =\lambda _{*}\), \(\lambda \in (\lambda _{*},+\infty )\), respectively.

Example 4.3

Consider \(f(u)=u+u^{p}\ (1< p\leq 2)\) for \(u>0\).

By calculation, \(f''(u)=p(p-1)u^{p-2}>0\) and \(uf'(u)-f(u)-\frac{1}{2}u^{2}f''(u)=\frac{1}{2}u^{p}(p-1)(2-p)\geq 0\), so f satisfies (H1), (H2). From \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r}=\lim_{r\to 0^{+}} \frac{r+r^{p}}{r}=1\), \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}f''(r)=+\infty \) as \(1< p<2\), and \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}f''(r)=p(p-1)\in (0,\infty )\) as \(p=2\), it is easy to verify that f satisfies (C2). Therefore, by Theorem 1.2, there exists \(0<\lambda _{*}<\lambda ^{*}=\frac{\pi ^{2}}{4L^{2}}\) such that problem (1.1) has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\lambda _{*})\), \(\lambda =\lambda _{*}\), or \(\lambda \geq \lambda ^{*}\), \(\lambda \in (\lambda _{*},\lambda ^{*})\), respectively.

Example 4.4

Consider \(f(u)=u\ln (a+u) (a>1)\) for \(u>0\).

By calculation, \(f''(u)=\frac{2a+u}{(a+u)^{2}}>0\), \(uf'(u)-f(u)-\frac{1}{2}u^{2}f''(u)=\frac{u^{3}}{2(a+u)^{2}}>0\) and \(\lim_{r\to 0^{+}}\frac{f(r)}{r}=\lim_{r\to 0^{+}} \frac{r\ln (a+r)}{r}=\ln a\in (0,+\infty ]\), so that (H1), (H2), and (C2) hold. Therefore, by Theorem 1.2, there exists \(0<\lambda _{*}<\lambda ^{*}=\frac{\pi ^{2}}{4L^{2}\ln a}\) such that problem (1.1) has zero, exactly one, or exactly two positive solutions according to \(\lambda \in (0,\lambda _{*})\), \(\lambda =\lambda _{*}\), or \(\lambda \geq \lambda ^{*}\), \(\lambda \in (\lambda _{*},\lambda ^{*})\), respectively.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Bereanu, C., Jebelean, P., Torres, P.J.: Positive radial solutions for Dirichlet problems with mean curvature operators in Minkowski space. J. Funct. Anal. 264, 270–287 (2013)

Bereanu, C., Jebelean, P., Torres, P.J.: Multiple positive radial solutions for a Dirichlet problem involving the mean curvature operator in Minkowski space. J. Funct. Anal. 265(4), 644–659 (2013)

Coelho, I., Corsato, C., Obersnel, F., Omari, P.: Positive solutions of the Dirichlet problem for the one-dimensional Minkowski-curvature equation. Adv. Nonlinear Stud. 12(3), 621–638 (2012)

Coelho, I., Corsato, C., Rivetti, S.: Positive radial solutions of the Dirichlet problem for the Minkowski-curvature equation in a ball. Topol. Methods Nonlinear Anal. 44(1), 23–39 (2014)

Dai, G.: Bifurcation and positive solutions for problem with mean curvature operator in Minkowski space. Calc. Var. Partial Differ. Equ. 55, 72 (2016)

Dai, G.: Global bifurcation for problem with mean curvature operator on general domain. Nonlinear Differ. Equ. Appl. 24, 30 (2017)

Dai, G., Wang, J.: Nodal solutions to problem with mean curvature operator in Minkowski space. Differ. Integral Equ. 30(5–6), 463–480 (2017)

Huang, S.-Y.: Exact multiplicity and bifurcation curves of positive solutions of a one-dimensional Minkowski-curvature problem and its application. Commun. Pure Appl. Anal. 17, 1271–1294 (2018)

Huang, S.-Y.: Classification and evolution of bifurcation curves for the one-dimensional Minkowski-curvature problem and its applications. J. Differ. Equ. 264, 5977–6011 (2018)

Ma, R., Chen, T., Gao, H.: On positive solutions of the Dirichlet problem involving the extrinsic mean curvature operator. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. 98, 1 (2016)

Ma, R., Gao, H., Lu, Y.: Global structure of radial positive solutions for a prescribed mean curvature problem in a ball. J. Funct. Anal. 270, 2430–2455 (2016)

Zhang, X., Feng, M.: Bifurcation diagrams and exact multiplicity of positive solutions of one-dimensional prescribed mean curvature equation in Minkowski space. Commun. Contemp. Math. 21(10), 1–15 (2018)

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the anonymous referee for his valuable suggestions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11801243 and No. 11961039), the Young Scholars Science Foundation of Lanzhou Jiaotong University (No. 2017012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors completed the main study, carried out the results of this article, and drafted the paper. The first author checked the proofs and verified the calculation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, H., Xu, J. Bifurcation curves and exact multiplicity of positive solutions for Dirichlet problems with the Minkowski-curvature equation. Bound Value Probl 2021, 81 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-021-01558-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-021-01558-x