Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are associated with high healthcare utilization. This systematic review aimed to summarize what is known about the impact of sex, income, and education on the likelihood of bowel surgery, hospitalization, and use of corticosteroids and biologics among patients with IBD.

Methods

We used EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Web of Science to perform a systematic literature search. Pooled hazard ratios (HRs) and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using random effects meta-analysis for the impact of sex on the likelihood of surgery and hospitalization. In addition, we performed subgroup analyses of the effect of IBD type (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) and age. Finally, meta-regression was undertaken for the year of publication.

Results

In total, 67 studies were included, of which 23 studies were eligible for meta-analysis. In the main meta-analysis, male sex was associated with an increased likelihood of bowel surgery (HR 1.42 (95% CI 1.13;1.78), which was consistent with the subgroup analysis for UC only (HR 1.78, 95% CI 1.16; 2.72). Sex did not impact the likelihood of hospitalization (OR 1.05 (95% CI 0.86;1.30), although the subgroup analysis revealed an increased likelihood of hospitalization in CD patients (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.28;1.58). In 9 of 10 studies, no significant sex-based differences in the use of biologics were reported, although in 6 of 6 studies, female patients had lower adherence to biologics. In 11 of 13 studies, no significant sex-based difference in the use of corticosteroids was reported. The evidence of the impact of income and education on healthcare utilization was sparse and pointed in different directions. The substantial heterogeneity between studies was explained, in part, by differences in IBD type and age.

Conclusions

The results of this systematic review indicate that male patients with IBD are significantly more likely to have surgery than female patients with IBD but are not, overall, more likely to be hospitalized, whereas female patients appear to have statistically significantly lower adherence to biologics compared to male patients. Thus, clinicians should not underestimate the impact of sex on healthcare utilization. Evidence for income- and education-based differences remains sparse.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42022315788.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), with their two main subtypes, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, associated with increased health resource utilization, ongoing monitoring, long-term medication, and occasionally the need for hospitalization and surgery [1, 2].

A step-up strategy is usually applied to treat mild-to-moderate IBD, starting with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and escalating to glucocorticoids and/or immunosuppressants, as necessary [3, 4]. Treatment with biologics is a well-known final treatment step with approximately 50% of patients starting this treatment within 2 years of diagnosis [5]. Finally, IBD patients with severe complications may undergo surgery and/or need to be hospitalized. Ten years after diagnosis 30–70% of patients with CD and 10–30% of patients with UC will undergo intestinal surgery [6,7,8]. Approximately 20% and 40% of patients with UC and CD are hospitalized within 5 years of diagnosis, respectively [9].

Individual treatment is highly dependent on disease phenotype, complications, severity, and activity [1, 2]. However, socio-demographic characteristics, such as education, income level, and sex, may also affect disease outcomes, impacting healthcare utilization, access, or need, as highlighted in previous literature reviews, although with contradictive conclusions [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. For example, low-income and economic deprivation have been associated with higher rates of hospitalization for patients with an IBD diagnosis [10, 11, 17, 18], but lower rates of surgery [10, 18], whereas the impact on surgery remains unclear in other studies [11]. Moreover, associations between low socioeconomic status and lower adherence to medical therapy for IBD have been found in some studies [19,20,21] but not in others [18, 22]. In addition, some research has reported the female sex as an independent predictor for non-adherence to biological treatment [13, 15], while others did not report any difference between male and female patients [16, 23]. The evidence that sex impacts healthcare utilization for IBD patients is likewise contradictory. In one large prospective study, sex was not identified as a predictor for surgery and cumulative medication use among IBD patients [23]. In contrast, other studies report male sex as an independent predictor for surgery [12, 24, 25], yet other studies demonstrated higher surgery rates in female patients [26, 27].

Sociodemographic differences may have consequences for the likelihood of complications and severe disease, adding to the burden of social inequality. Although previous reviews addressing this topic are available, they are either out of date or have discordant or limited results, and the impact of sex and socioeconomic status on healthcare access and utilization for IBD patients thus, remains uncertain. Defining the sociodemographic determinants affecting healthcare utilization has important clinical and societal implications, such as improving our understanding of which factors to consider in both future studies and clinical practice.

We aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of socio-demographic characteristics, including income, education, and sex, on the likelihood of bowel surgery, hospitalization, and use of corticosteroids and biologics in observational studies of patients with IBD.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies for this systematic literature review included patients (children and adults) diagnosed with IBD. Studies of socioeconomic status were only included if they measured income or educational level. Accepted study designs were peer-reviewed observational studies, including cohort, case–control, cross-sectional studies, and uncontrolled trials. Published abstracts, letters to the editor, editorials, and theses were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

In April 2022, Embase, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases were searched systematically for observational studies examining associations between the sociodemographic factors of sex, income, and educational status and four outcomes: likelihood of bowel surgery, hospitalization, use of corticosteroids and treatment with biologics. Three search blocks were used: one for IBD combined with “and” with a block for sex and a block for income and education, respectively. In addition, a “year” filter [2012–2021] was applied to all four databases. The search was updated in February 2024 with publication dates 01.01.2022–29.02.2024.

The complete search strategy is presented in Additional file 1: Table A1. The review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [28] and registered in the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) [Registration ID: CRD42022315788] shortly after the searches were initiated and before the analyses were conducted.

There were minor variations in the methods between the planned protocol (as registered in PROSPERO) and the study’s methodology, i.e., the end date of searches was in February 2024 rather than January 2022. Moreover, grey literature was not searched as planned, and snowballing via reference lists of included and excluded studies was not undertaken due to the comprehensive number of studies achieved from the database searches. Hospitalization was defined as “yes” or “no” to any hospitalization regardless of the frequency of reported hospitalizations.

Selection process and data items

Screening and data extraction were performed independently by the first author Nathalie Fogh Rasmussen (NFR) and one of three other authors: LHG, CM, and ZH, using the systematic review screening tool, Covidence [29], and articles were assigned at random between LHG, CM, and ZH. Any discrepancies were resolved by NFR and one of the three other reviewers, and a third reviewer (LHG, CM, or ZH) was involved as required.

Data were extracted from all selected studies, including author, publication year, study period, data source, study design, index event, patient age (children/adult), IBD type (CD or UC), number of patients with IBD and subgroups, independent variable (sex, income or education), primary outcomes of interest, covariates, effect estimates, and main findings.

Outcomes were included if presented as frequency and percentage (N (%)), relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), or hazard ratio (HR). Surgery was defined as any first-occurring bowel surgery. Hospitalization was defined as a hospital stay/inpatient/readmission visit for any reason but excluded outpatient/ambulatory or emergency room visits. The use of corticosteroids and biological treatment was defined as any dose or duration of the medication. Studies of adherence or discontinuation of corticosteroids and biological treatment were also included.

Study risk of bias assessment

Quality assessment of included studies was conducted using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies [30]. Although not indicated in the PROSPERO record, GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) [31] was applied to studies included in the meta-analysis to assess the certainty of the body of evidence. The certainty of the evidence was classified as high, moderate, low, or very low. Two independent investigators conducted this process (CM and NFR), and disagreements were solved by discussion.

Effect measures and synthesis methods

Analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2 + (R markdown using metaphor and E-value package). Studies eligible for meta-analysis included studies of sex if they were similar according to the type of outcome measurement, type of effect size (HR), and study design. If the number of studies calculating HRs was < 4 for a given outcome, studies calculating OR were used instead (if the number of these studies was > / = 4). Some effect estimates were converted to ensure consistency in using the female sex as the reference level.

A random-effects (RE) model using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method [32] was chosen to calculate the average distribution of associations. Where high between-study consistency was present, a fixed effect model was applied in the subgroup analyses. Where available, adjusted effect estimates presented for each study were used. Studies with more than one outcome measure (e.g., two types of surgery) were duplicated in the meta-analysis.

Between-study heterogeneity was assessed by inspecting the forest plots and by calculating the tau-squared \({({\varvec{\tau}}}^{2})\) and the I-squared statistics \({(I}^{2})\) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Subgroup analyses and meta-regression were undertaken to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. Subgroup analysis was undertaken for the categorical variables IBD type (CD/UC), age (children/adults), and country. Meta-regression was undertaken for the continuous variable “year of publication”. Furthermore, in a sensitivity analysis, the heterogeneity between univariate studies was compared to the heterogeneity between multivariate studies to examine the causes of heterogeneity. Publication bias was evaluated using a visual inspection of funnel plots’ symmetry.

Results

Summary of studies

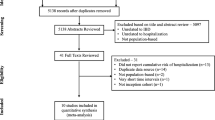

In total, 14,894 records were identified in the search. After removing duplicates, 10,616 records were screened, from which 404 full-texts were reviewed, and 67 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1).

Most studies were retrospective in design (73.5%) (Additional file 2: Table A2). Patients with CD were included in 77.6% of studies, and patients with UC were included in 71.6% of studies. In total, 65 (97.0%) studies reported sex, 10 (14.9%) income, and 6 (9%) education as independent variables.

In total, 23 studies were eligible for meta-analysis as they were similar according to the definition of the independent variable (only sex was comparable across studies), type of outcome measurement, type of effect size, and study design.

Bowel surgery

A total of 41 studies (61.2%) compared the rates or frequency of bowel surgery between males and females [25, 26, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. Of these, 22 (53.7%) reported statistically significant sex-based differences in the likelihood of bowel surgery [25, 26, 33, 35, 39, 40, 44, 47, 50,51,52,53, 55, 56, 58, 62,63,64, 66, 67, 69, 70] (Table 1). Of these 22 studies, 19 reported that males had a higher likelihood of bowel surgery than females.

The effect estimates of studies on sex differences eligible for meta-analysis (14 studies for surgery) were pooled to present an overall HR of 1.42 (95% CI 1.13; 1.78, Fig. 2), indicating a higher rate/probability of surgery among male patients than female patients. The heterogeneity measures for surgery showed an I2 = 86.19 [54.73; 94.93]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.15 [0.03; 0.45], which suggests substantial heterogeneity between the studies included.

Forest plot of RE model meta-analysis of HRs for the likelihood of surgery across included studies

Forest plot of RE model meta-analysis of HRs for the likelihood of surgery in male patients compared to female patients with IBD across included studies. Reference: female patients. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NA, not applicable; RE, random effects

A total of six studies (9%) compared bowel surgery across income groups [33, 38, 44, 60, 72, 74], and three of these (50%) identified statistically significant income-based differences, with two of the three studies indicating that individuals with a lower income had a lower likelihood of bowel surgery [44, 74]. Conversely, only two studies (3%) examined education level and the likelihood of surgery and found no statistically significant associations [60, 73].

In subgroup analyses, the pooled estimate for the likelihood of surgery in males compared to females was statistically significant for studies of UC (HR 1.78 [95% CI 1.16;2.72]), whereas not for studies of CD (HR 1.32 [95% CI 0.92;1.89]), with a higher likelihood among males than females (Fig. 3). The estimate for I2 in the CD analysis is wider but has consistently lower values for both I2 and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) (CD (I2 = 69.42 [12.13;94.82]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.08 [0.005;0.67]) versus UC: (I2 = 87.95 [31.76;98.43]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.14 [0.009;1.17]). Thus, the IBD type may explain some of the between-study heterogeneity in the main RE model.

Forest plot of subgroup (CD/UC) meta-analysis of HRs for risk of surgery

Forest plot of RE model subgroup meta-analysis of HRs for risk of surgery in male patients compared to female patients with IBD by IBD subtype. Reference: female patients. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NA, not applicable; RE, random effects

When stratifying the studies of surgery by age, a statistically significant sex difference was found for studies of adults (HR 1.57 [95% CI 1.13;2.18]), but not for those of children (HR 1.02 [95% CI 0.80;1.29]), with a higher likelihood of surgery among adult males compared to adult females (Fig. 4). A fixed effects model was undertaken for studies of children instead of a random effects model for adults, as the between-study heterogeneity was too low to be estimated sufficiently, with only three studies focusing on children separately. For the adult model, the overall study heterogeneity was also low (\({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.07 [0.00;0.59]). Based on the low heterogeneity measures, stratification by children/adults may explain some of the between-study heterogeneity in the main RE model.

Forest plot of subgroup (children/adults) meta-analysis of HRs for risk of surgery

Forest plot of RE model subgroup meta-analysis of HRs for risk of surgery in male patients compared with female patients with IBD by children and adults subgroups. Reference: female patients. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NA, not applicable; RE, random effects

Further subgroup analyses by country revealed that the country where the study was conducted might also explain some of the between-study heterogeneity in the main RE model (Fig. 5).

Forest plot of subgroup (country) meta-analysis of HRs for risk of surgery

Forest plot of RE model subgroup meta-analysis of HRs for risk of surgery in male patients compared with female patients with IBD by country. Reference: female patients. Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NA, not applicable; RE, random effects

Hospitalization

In 17 studies (25.4%) comparing the likelihood of hospitalization by sex [26, 38, 41, 48, 51, 64, 71, 75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84], male patients were significantly more likely to be hospitalized in 8 studies [38, 48, 75, 76, 81,82,83,84], female patients were significantly more likely to be hospitalized in 2 studies [64, 80], and there was no significant difference in 7 studies [26, 41, 51, 71, 77,78,79] (Table 2).

In meta-analysis, an overall OR of 1.05 (95% CI 0.86;1.30, Fig. 6) was estimated for the 9 eligible studies, indicating no statistically significant sex difference in the rate/probability of hospitalization. The heterogeneity measures showed an I2 = 86.76 [65.28;95.31]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.10 [0.03;0.31], indicating substantial heterogeneity between the studies.

Forest plot of RE model meta-analysis of ORs for the likelihood of hospitalization across included studies

Forest plot of RE model meta-analysis of ORs for the likelihood of hospitalization in male patients compared to female patients with IBD across included studies. Reference: female patients. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NA, not applicable; RE, random effects

Three studies (4.5%) compared hospitalization across income groups [72, 81, 83], of which two studies (66.7%) identified a statistically significant association between high income and a lower likelihood of hospitalization [72, 81]. No studies examining the association between educational level and likelihood of hospitalization were identified.

In the subgroup analyses, the male sex was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of hospitalization among patients with CD (OR 1.41 [95% CI 1.08;1.84]), but not UC (OR 0.94 [95% CI 0.54;1.62]) (Fig. 7). The overall heterogeneity in both RE models was very low (I2 = 5.97 [0.00;93.11]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.003 [0.000;0.55] and I2 = 5.97 [0.00;93.11]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.003 [0.000;0.55], respectively). Subgroup analysis on children/adults and country was not undertaken because of the low number of studies in the children subgroup (two), and the fact that most studies were from the USA (seven of nine studies).

Forest plot of subgroup (CD/UC) meta-analysis of ORs for risk of hospitalization

Forest plot of RE model subgroup meta-analysis of ORs for risk of hospitalization in male patients compared to female patients with IBD by IBD subtype. Reference: female patients. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NA, not applicable; RE, random effects

Use of corticosteroids

A total of 13 studies (19.4%) examined corticosteroid use [36, 42, 45, 59, 64, 70, 72, 75, 85,86,87,88,89] (Table 3), of which only 2 studies (15.4%) reported a statistically significant sex-based difference in the use of corticosteroids, with fewer male patients using a corticosteroid (budesonide) than female patients for both CD and UC in one study [64] and fewer female patients using steroids for total IBD patients in the other study [89].

No studies examining adherence to corticosteroids were found.

One study (1.5%) compared corticosteroid use across income groups and concluded that those with lower income were more likely to take corticosteroids [72]. However, no studies on educational level and use of corticosteroids were found.

Use of biological therapy

Twelve studies (17.9%) examined the use of biologics [26, 36, 42, 60, 64, 70, 72, 86, 87, 90,91,92] (Table 4). Only 2 studies found statistically significant sex differences, with female CD patients having a lower probability of using biologics than male patients in one study [64], and a similar association, but for UC patients only, in the other study [92].

Six studies (9%) examined adherence to biological treatment, and all reported statistically significantly lower adherence to biologics among female compared to male patients [45, 93,94,95,96,97].

None of the 4 studies (6%) examining income-related differences in the use of biological treatment [60, 72, 91, 92] reported a statistically significant association. One study [92] found an association between the highest level of education (master’s degree or higher) and a lower likelihood of biological treatment compared to the lowest education (college or less) in CD patients and overall IBD. One study (1.5%) examined educational differences in adherence to biological treatment and found no statistically significant association between educational status and adherence [97] (Table 4).

Meta-analysis was not relevant to studies reporting on corticosteroids and biological treatment due to the considerable variation in study designs and reporting of effect size.

Meta-regression

In studies of surgery, meta-regression of the year of publication revealed a tendency towards smaller differences between males and females, the more recent the publication, although this trend was not statistically significant (Additional file 5: Figure A1). Measures of heterogeneity were lower in the meta-regression (I2 = 75.51 [54.75;95.18]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.08 [0.03;0.49]) than in the main meta-analysis (I2 = 86.19 [54.73;94.93]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.15 [0.03;0.45]), although not substantially different. Thus, this could indicate that the year of publication may explain some of the overall between-study heterogeneity in the main RE model of surgery.

In the studies of hospitalization, meta-regression of the year of publication revealed a tendency towards an increasing difference between males and females in the likelihood of hospitalization the more recent the publication, although not statistically significant (Additional file 5: Figure A2). The between-study heterogeneity was slightly lower (I2 = 84.57 [62.03;96.08]% and \({{\varvec{\tau}}}^{2}\) = 0.10 [0.03;0.44]) compared to the heterogeneity in the main meta-analysis (see above). These results do not indicate a significant effect of publication year on the between-study heterogeneity for hospitalization.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

In sensitivity analyses comparing studies of univariate analyses with studies of multivariate analyses, we found that the overall heterogeneity was high in both RE models for surgery (Additional file 5: Figure A3). In contrast, the univariate model had a very low heterogeneity compared to the multivariate model of studies of hospitalization (Additional file 5: Figure A4). Thus, excluding univariate studies would not lower the heterogeneity, probably due to the high heterogeneity of the covariates included in the multivariate models, which made them less comparable, and/or due to unadjusted confounding.

Inspection of funnel plots indicated no significant risk of publication bias (Additional file 5: Figure A5 and Figure A6).

Study quality assessment

All included cohort or case–control studies (N = 53) scored between 5 and 9 on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for quality assessment, with 88.7% of these studies scoring 7 or above, indicating a high-quality methodology (Additional file 3: Table A3). However, in total, 16 studies (23.9% of all included studies) reported only descriptive statistics (N (%), p-value) and no relative risk estimates, lowering the quality. Furthermore, the quality of evidence was lowered in the GRADE assessment to “very low” due to high inconsistency and indirectness when comparing outcomes across studies (Additional file 4: Table A4).

Discussion

This systematic review identified 67 studies reporting the impact of sex (65 studies (97.0%)), income (10 studies (14.9%)) and education (6 studies (9%)) on the likelihood of bowel surgery, hospitalization, and use of corticosteroids and biologics in patients with IBD. In the meta-analysis, we observed the male sex to be significantly associated with a higher likelihood of bowel surgery, whereas sex did not impact the likelihood of hospitalization. Evidence of education- and income-related differences was minimal, with only a few studies identified for all four types of healthcare utilization, each pointing in a different direction. There was a high degree of heterogeneity among the studies, which we attempted to account for in the subgroup analyses and meta-regression.

Sex and likelihood of surgery and hospitalization

In CD patients, sex had an influence on the likelihood of hospitalization, with a higher likelihood among men, but not on surgery, whereas in UC patients, sex was associated with surgery, with a higher likelihood among men, but it was not associated with hospitalization. Although sex-based differences were found, many studies reported no statistically significant sex differences in either the likelihood of surgery or hospitalization [26, 34, 36,37,38, 41,42,43, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51, 54, 57, 59,60,61, 65, 68, 71, 76,77,78,79,80, 84]. Similar results were observed in a review by Rustgi et al., that reported males generally undergo more IBD-related surgery than females [12], yet another study from the review by Rustgi et al. revealed higher probabilities among female patients [27].

Sex and use of corticosteroids and biologics

In this review, only 2 of the 13 studies found statistically significant sex-based differences in corticosteroids, and with contradictive results [64, 89]. No studies examining sex and adherence to corticosteroids were identified. Contrary to this, all 6 studies of adherence to biologics and 2 of 11 studies examining the use of biologics found a statistically significantly lower adherence or lower probability of females using biologics compared to males [45, 64, 92,93,94,95,96,97]. These findings are similar to previous reviews [13, 15], which reported that the female sex was one of the most reliable predictors of non-adherence, and males were more likely to receive systemic treatments (including biologics) than females. A possible explanation may be a poorer response and effect of biologics in female patients, as reported in cohort studies [98, 99], that could affect adherence to medical treatment.

Possible sex biases influencing the findings

Evidence is accumulating of underlying biological mechanisms explaining sex-based differences in IBD, including the association between sex hormones with susceptibility to IBD, the severity of symptoms, and disease progression [13, 100,101,102,103,104]. One study in this review suggested that more frequent ileal involvement in men with IBD has resulted in more bowel resections in men compared to women [26]. Moreover, there is evidence that males have a higher rate of colorectal cancer than females]13], which may also have contributed to differences in the likelihood of surgery between males and females. Finally, the observed higher likelihood of hospitalization may be associated with a higher likelihood of surgery. Shared decision-making is an important part of the therapeutic strategy for IBD and gives patients input into decisions about their care, including whether to have surgery or start medical treatment. Thus, patient preferences and concerns have a great impact on decision-making. For example, some women may be more likely to avoid a colectomy due to concerns about body image or future fertility after surgery [105]. Having surgery and receiving medical treatment should, thus, not solely be considered risks. It may also be a risk not to have surgery or delay medical treatment. If a lack of or delay of surgery or medical treatment negatively affects IBD worsening the clinical trajectory, then it could indicate undertreatment and health inequity. Finally, several studies in this review still report no statistically significant sex differences.

Income and education and the likelihood of surgery and hospitalization

The impact of socioeconomic status often varies across studies due to different definitions of socioeconomic status. In this review, income and education were used as socioeconomic measures. However, the definition of income and education also varied across studies, resulting in very contradictive findings among the 9 included studies of associations between income and education and the likelihood of surgery or hospitalization [33, 38, 44, 60, 72,73,74, 81, 83]. Furthermore, the included studies were not directly comparable to findings from a recently published systematic review [14], which included measurements of socioeconomic status based on medical insurance.

Income and education and use of corticosteroids and biologics

Very few studies examined income and education-related differences in using corticosteroids and biologics. One study reported that those with a lower income were more likely to take corticosteroids [72], and another study found an association between the highest education level and biological treatment use [92]. Finally, other studies reported no statistically significant differences. Sewell et al., also reported varying results, with one study from the review reporting no statistically significant differences in the use of steroids between deprived and non-deprived [18], and two studies reporting no significant income or educational differences in adherence to medical therapy generally [22, 106].

Possible socioeconomic biases influencing the findings

Studies have linked low income and education to an increased likelihood of developing severe disease outcomes in various chronic disorders, suggesting underlying explanatory factors such as more severe chronic disease among individuals with low education are due to an unhealthier lifestyle [107,108,109,110,111]. Moreover, many of these were conducted in countries with healthcare access based on insurance status and non-universal healthcare coverage. Therefore, the reported differences concerning income and education may suggest that income and education are more of an indicator of lower access to surgical treatment than a reflection of a biologically lower likelihood of requiring surgery. However, there is currently no well-founded explanation for the observed differences.

Strengths and limitations of the evidence included and of the review processes used

A major strength of this review is the unification of studies on sex, income, and education as socio-demographic predictors for IBD healthcare. A major strength is also the discussion of evidence from studies included in the meta-analysis and studies not eligible for inclusion. Furthermore, only studies with the same study design (retrospective cohort studies) and effect size measure were included in the meta-analysis to ensure comparability. In addition, a systematic approach was used based on the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews, and the choice of search terms was made with the guidance of an experienced health sciences librarian and lastly, screening and data extraction were performed independently by two persons.

A major limitation of this review is the lack of evidence for explaining observed differences. For sex, it may be a mixture of biological factors and individual health behavior. Another limitation is the low-GRADE score for the outcomes and the degree of between-study heterogeneity. The subgroup analyses revealed that the type of IBD, age group of patients, the country where the study was conducted, and publication year could explain some of this heterogeneity. The high heterogeneity is, in part, due to the broad inclusion/exclusion criteria used in the systematic literature search, such as the inclusion of both children and adults, all countries, and varying definitions of surgery, hospitalization, and use of medical treatment.

It is also a limitation that none of the included studies had clearly defined sex or gender. The use of sex/gender varied across the included studies, with 37 studies (55.2%) using the word “sex” while 11 studies (16.4%) used the word “gender”, and 19 studies (28.4%) using a mixture of both words. There were only three studies that defined sex as “biological sex” and gender as a socially constructed definition. Thus, for this review, sex and gender were combined and one-word “sex” was used to describe biological sex. Lastly, we found a minimal number of studies examining the association between educational and income-related differences and all four types of healthcare utilization. This lack of studies could be due to the search terms. For example, “education” was considered too broad and not included in the search block. In addition, we excluded studies using surrogate measures for socioeconomic status, such as insurance status, as, in many countries, healthcare is not based on a healthcare insurance system.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive update of our knowledge of sex-, income-, and education-based differences in IBD. The review reports on results from high-quality cohort studies showing that male patients are more likely to have surgery and be hospitalized than female patients with IBD, although only significant for surgery in the meta-analysis. In contrast, the evidence of sex-, income-, and education-based differences for using corticosteroids or biologics was sparse, except for adherence to biologics, where high-quality studies found statistically significantly lower adherence to biologics among female patients compared to male patients. Nevertheless, the review revealed considerable heterogeneity between the studies. In summary, this review underlines that it is important to consider IBD patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, especially sex, in both future studies and clinical practice, since they can be significant explanatory variables and/or confounders for healthcare outcomes and patients may have different needs for social support in relation to the shared healthcare decision-making process. Although it could be argued that sex per se may influence the severity of IBD and hence the assessed outcomes, there is no obvious explanation for the income- and education-based differences. However, the impact of patient preferences, health literacy, healthcare systems, and differential access to care by sex and socioeconomic status on patient outcomes should not be underestimated. Identifying such underlying associations will provide policymakers with an evidence base to target interventions against inequality in the use of healthcare.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Abbreviations

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

- 5-ASA:

-

5-Aminosalicylic acid

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations

- RE:

-

Random effects

- EE:

-

Equal effects

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Burisch J, Vardi H, Schwartz D, Friger M, Kiudelis G, Kupčinskas J, et al. Health-care costs of inflammatory bowel disease in a pan-European, community-based, inception cohort during 5 years of follow-up: a population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):454–64.

Alatab S, Sepanlou SG, Ikuta K, Vahedi H, Bisignano C, Safiri S, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17–30.

Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1741–55.

Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756–70.

Zhao M, Sall Jensen M, Knudsen T, Kelsen J, Coskun M, Kjellberg J, et al. Trends in the use of biologicals and their treatment outcomes among patients with inflammatory bowel diseases – a Danish nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(5):541–57.

Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Hair C, Wilson J, Ding NS, Heerasing N, et al. Prospective population-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease in the biologics era: Disease course and predictors of severity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(9):1346–53.

Vester-Andersen MK, Prosberg MV, Jess T, Andersson M, Bengtsson BG, Blixt T, et al. Disease course and surgery rates in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based, 7-year follow-up study in the era of immunomodulating therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(5):705–14.

Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1785–94.

Tsai L, Nguyen NH, Ma C, Prokop LJ, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis: risk of hospitalization in patients with ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease in population-based cohort studies. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(6):2451–61.

Sewell JL, Velayos FS. Systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(3):627–43.

Wardle RA, Wardle AJ, Charadva C, Ghosh S, Moran GW. Literature review: impacts of socioeconomic status on the risk of inflammatory bowel disease and its outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(8):879–84.

Rustgi SD, Kayal M, Shah SC. Sex-based differences in inflammatory bowel diseases: a review. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:175628482091504.

Goodman WA, Erkkila IP, Pizarro TT. Sex matters: impact on pathogenesis, presentation and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(12):740–54.

Booth A, Ford W, Brennan E, Magwood G, Forster E, Curran T. Towards Equitable Surgical Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review of Disparities in Surgery for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(9):1405–19.

Lopez A, Billioud V, Peyrin-Biroulet C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Adherence to Anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(7):1528–33.

Lenti MV, Selinger CP. Medication non-adherence in adult patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review and update of the determining factors, consequences and possible interventions. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11(3):215–26.

Benchimol EI, To T, Griffiths AM, Rabeneck L, Guttmann A. Outcomes of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: socioeconomic status disparity in a universal-access healthcare system. J Pediatr. 2011;158(6):960-7.e1-4.

Nahon S, Lahmek P, Macaigne G, Faurel J-P, Sass C, Howaizi M, et al. Socioeconomic deprivation does not influence the severity of Crohnʼs disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(4):594–8.

Ediger JP, Walker JR, Graff L, Lix L, Clara I, Rawsthorne P, et al. Predictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7):1417–26.

Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, Hanauer SB. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2929–33.

Tripathi K, Dong J, Mishkin BF, Feuerstein JD. Patient preference and adherence to aminosalicylates for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2021;14:343–51.

Nguyen GC, Laveist TA, Harris ML, Datta LW, Bayless TM, Brant SR. Patient trust-in-physician and race are predictors of adherence to medical management in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1233–9.

Romberg-Camps MJ, Dagnelie PC, Kester AD, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Cilissen M, Engels LG, et al. Influence of phenotype at diagnosis and of other potential prognostic factors on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):371–83.

Mazor Y, Maza I, Kaufman E, Ben-Horin S, Karban A, Chowers Y, et al. Prediction of disease complication occurrence in Crohn’s disease using phenotype and genotype parameters at diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):592–7.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Harmsen WS, Tremaine WJ, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ, Loftus EV Jr. Surgery in a population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease from Olmsted County, Minnesota (1970–2004). Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1693–701.

Severs M, Spekhorst LM, Mangen M-JJ, Dijkstra G, Lowenberg M, Hoentjen F, et al. Sex-Related Differences in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results of 2 Prospective Cohort Studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(6):1298–306.

Wagtmans MJ, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB, van Hogezand RA. Gender-related differences in the clinical course of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(5):1541–6.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, PRISMA, et al. explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021: n160.

Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. www.covidence.org

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M,et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing thequality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available from: URL: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. [cited 2022 Nov 29].

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–6.

Inthout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):25.

Abou Khalil M, Boutros M, Nedjar H, Morin N, Ghitulescu G, Vasilevsky C-A, et al. Incidence rates and predictors of colectomy for ulcerative colitis in the era of biologics: results from a provincial database. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22(1):124–32.

Akintimehin AO, O'Neill RS, Ring C, Raftery T, Hussey S, Dochas S. Outcomes of a National Cohort of Children with Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:48.

Chhay V, Saxena S, Cecil E, Chatu S, Subramanian V, Curcin V, et al. The impact of timing and duration of thiopurine treatment on colectomy in ulcerative colitis: A national population-based study of incident cases between 1989–2009. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(1):87–98.

Dotson JL, Bricker JB, Kappelman MD, Chisolm D, Crandall WV. Assessment of sex differences for treatment, procedures, complications, and associated conditions among adolescents hospitalized with crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(11):2619–24.

Eder P, Klopocka M, Wisniewska-Jarosinska M, Talar-Wojnarowska R, Maj D, Detka-Kowalska I, et al. Possible undertreatment of women with Crohn disease in Poland A subgroup analysis from a prospective multicenter study of patients on anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Polish Arch Int Med Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnętrznej. 2017;127(10):674–80.

Gajendran M, Umapathy C, Loganathan P, Hashash J, Koutroubakis I, Binion D, et al. Analysis of hospital-based emergency department visits for inflammatory bowel disease in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(2):389–99.

Gao X, Yang RP, Chen MH, Xiao YL, He Y, Chen BL, et al. Risk factors for surgery and postoperative recurrence: Analysis of a south China cohort with Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(10):1181–91.

Goel A, Dutta AK, Pulimood AB, Eapen A, Chacko A. Clinical profile and predictors of disease behavior and surgery in Indian patients with Crohn’s disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32(3):184–9.

Gracie DJ, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Longitudinal impact of IBS-type symptoms on disease activity, healthcare utilization, psychological health, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):702–12.

Herzog D, Buehr P, Koller R, Rueger V, Heyland K, Nydegger A, et al. Gender differences in paediatric patients of the swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort study. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2014;17(3):147–54.

Kim HJ, Oh SH, Kim DY, Lee H-S, Park SH, Yang S-K, et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes of paediatric crohn’s disease: a single-centre experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(2):157–64.

King D, Rees J, Mytton J, Harvey P, Thomas T, Cooney R, et al. The Outcomes of Emergency Admissions With Ulcerative Colitis Between 2007 and 2017 in England. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(6):764–72.

Lie M, Kreijne JE, van der Woude CJ. Sex is associated with adalimumab side effects and drug survival in patients with crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(1):75–81.

Magro F, Dias CC, Portela F, Miranda M, Fernandes S, Bernardo S, et al. Development and validation of risk matrices concerning ulcerative colitis outcomes-bayesian network analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(4):401–9.

Meregaglia M, Banks H, Fattore G. Hospital burden and gastrointestinal surgery in inflammatory bowel disease patients in Italy: a retrospective observational study. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9(10):853–62.

Osamura A, Suzuki Y. Fourteen-Year Anti-TNF therapy in crohn’s disease patients: clinical characteristics and predictive factors. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(1):204–8.

Rinawi F, Assa A, Hartman C, Glassberg YM, Friedler VN, Rosenbach Y, et al. Incidence of bowel surgery and associated risk factors in pediatric-onset crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(12):2917–23.

Rinawi F, Assa A, Eliakim R, Mozer-Glassberg Y, Nachmias-Friedler V, Niv Y, et al. Risk of colectomy in patients with pediatric-onset ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(4):410–5.

Samuel S, Ingle SB, Dhillon S, Yadav S, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Cumulative incidence and risk factors for hospitalization and surgery in a population-based cohort of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(9):1858–66.

Sato Y, Matsui T, Yano Y, Tsurumi K, Okado Y, Matsushima Y, et al. Long-term course of Crohn’s disease in Japan: Incidence of complications, cumulative rate of initial surgery, and risk factors at diagnosis for initial surgery. J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Australia). 2015;30(12):1713–9.

Sceats LA, Morris AM, Bundorf MK, Park KT, Kin C. Sex differences in treatment strategies among patients with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort analysis of privately insured patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(5):586–94.

Solberg IC, Hoivik ML, Cvancarova M, Moum B, Ibsen Study G. Risk matrix model for prediction of colectomy in a population-based study of ulcerative colitis patients (the IBSEN study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(12):1456–62.

Stokes AL, Kulaylat AN, Rocourt DV, Hollenbeak CS, Koltun W, Falaiye T. Rates and trends for inpatient surgeries in pediatric Crohn’s disease in the United States from 2003 to 2012. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(7):1334–8.

Sun X-W, Wei J, Yang Z, Jin X-X, Wan H-J, Yuan B-S, et al. Clinical features and prognosis of crohn’s disease with upper gastrointestinal tract phenotype in chinese patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(11):3291–9.

Tanaka M, Takagi T, Naito Y, Uchiyama K, Hotta Y, Toyokawa Y, et al. Low serum albumin at admission is a predictor of early colectomy in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. JGH Open. 2021;5(3):377–81.

Targownik LE, Singh H, Nugent Z, Bernstein CN. The epidemiology of colectomy in ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(8):1228–35.

Targownik LE, Nugent Z, Singh H, Bernstein CN. Prevalence of and outcomes associated with corticosteroid prescription in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(4):622–30.

Timmer A, Stark R, Peplies J, Classen M, Laass MW, Koletzko S. Current health status and medical therapy of patients with pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a survey-based analysis on 1280 patients aged 10–25 years focusing on differences by age of onset. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(11):1276–83.

Winder O, Fliss-Isakov N, Winder G, Scapa E, Yanai H, Barnes S, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic balloon dilatation of intestinal strictures in patients with Crohn's disease. Medicine. 2019;98(35):e16864.

Wong JJ, Sceats L, Dehghan M, Wren AA, Sellers ZM, Limketkai BN, et al. Depression and health care use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(1):19–26.

Zhao M, Lo BZS, Vester-Andersen MK, Vind I, Bendtsen F, Burisch J. A 10-year follow-up study of the natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease in a danish population-based inception cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(7):1227–36.

Heath EM, Kim RB, Wilson A. A Comparative Analysis of Drug Therapy, Disease Phenotype, and Health Care Outcomes for Men and Women with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(9):4287–94.

De Cristofaro E, Salvatori S, Marafini I, Zorzi F, Alfieri N, Musumeci M, et al. Long-Term Risk of Colectomy in Patients with Severe Ulcerative Colitis Responding to Intravenous Corticosteroids or Infliximab. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1679.

Lee Y, Andrew L, Hill S, An KR, Chatroux L, Anvari S, et al. Disparities in access to minimally invasive surgery for inflammatory bowel disease and outcomes by insurance status: analysis of the 2015 to 2019 National Inpatient Sample. Surg Endosc. 2023;37(12):9420–6.

Stamatiou D, Naumann DN, Foss H, Singhal R, Karandikar S. Effects of ethnicity and socioeconomic status on surgical outcomes from inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37(6):1367–74.

Wan J, Shen J, Wu X, Zhong J, Chen Y, Zhu L, et al. Geographical heterogeneity in the disease characteristics and management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, the preliminary results of a Chinese database for IBD (CHASE-IBD). Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231210368.

Wang MY, Zhao JW, Wang HR, Zheng CQ, Chang B, Sang LX. Methotrexate showed efficacy both in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, predictors of surgery were identified in patients initially treated with methotrexate monotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:996065.

Liu Y, Söderberg J, Chao J. Adherence to and Persistence with Adalimumab Therapy among Swedish Patients with Crohn's Disease. Pharmacy (Basel). 2022;10(4):87.

Nguyen NH, Luo J, Paul P, Kim J, Syal G, Ha C, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Biologic Therapy in Hispanic Vs Non-Hispanic Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A CA-IBD Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(1):173-81.e5.

Bernstein CN, Walld R, Marrie RA. Social determinants of outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(12):2036–46.

Li Y, Ren J, Wang G, Gu G, Wu X, Ren H, et al. Diagnostic delay in Crohn’s disease is associated with increased rate of abdominal surgery: A retrospective study in Chinese patients. Digest Liver Dis. 2015;47(7):544–8.

McLoughlin RJ, Klouda A, Hirsh MP, Cleary MA, Lightdale JR, Aidlen JT. Socioeconomic disparities in the comorbidities and surgical management of pediatric Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2020;88(6):887–93.

Axelrad JE, Sharma R, Laszkowska M, Packey C, Rosenberg R, Lebwohl B. Increased healthcare utilization by patients with inflammatory bowel disease covered by medicaid at a tertiary care center. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(10):1711–7.

Barnes EL, Kochar B, Long MD, Martin CF, Crockett SD, Korzenik JR, et al. The Burden of Hospital Readmissions among Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr. 2017;191:184-+.

Chudy-Onwugaje K, Mamunes AP, Schwartz DA, Horst S, Cross RK. Predictors of high health care utilization in patients with inflammatory bowel disease within 1 year of establishing specialist care. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(3):325–35.

Gunnells D, Morris M, DeRussy A, Gullick A, Cannon J, Hawn M, et al. Racial disparities in readmissions for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) after colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(5): e142.

Limsrivilai J, Stidham RW, Govani SM, Waljee AK, Huang W, Higgins PDR. Factors That Predict High Health Care Utilization and Costs for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(3):385-+.

Mandel MD, Balint A, Golovics PA, Vegh Z, Mohas A, Szilagyi B, et al. Decreasing trends in hospitalizations during anti-TNF therapy are associated with time to anti-TNF therapy: Results from two referral centres. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46(11):985–90.

Micic D, Gaetano JN, Rubin JN, Cohen RD, Sakuraba A, Rubin DT, et al. Factors associated with readmission to the hospital within 30 days in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182900.

Mudireddy P, Scott F, Feathers A, Lichtenstein GR. Inflammatory bowel disease: predictors and causes of early and late hospital readmissions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(10):1832–9.

Poojary P, Saha A, Chauhan K, Simoes P, Sands BE, Cho J, et al. Predictors of hospital readmissions for ulcerative colitis in the United States: A national database study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(3):347–56.

Reja M, Hajela N, Makar M, Marino D, Bhurwal A, Rustgi V. One-year risk of opioid use disorder after index hospitalization for inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35(11):2081–7.

da Silva BC, Lyra AC, Mendes CMC, Ribeiro CPO, Lisboa SRO, de Souza MTL, et al. The Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Ulcerative Colitis in a Northeast Brazilian Population. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:359130.

Lee GJ, Kappelman MD, Boyle B, Colletti RB, King E, Pratt JM, et al. Role of sex in the treatment and clinical outcomes of pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(6):701–6.

McKenna NP, Dozois EJ, Pemberton JH, Lightner AL. Impact of sex on 30-day complications and long-term functional outcomes following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(5):619–25.

Barkan R, Shpoker L, Abboud R, Nafrin S, Ilsar T, Ofri L, et al. Factors associated with corticosteroid use in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients in Israel: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Dig Liver Dis. 2024;56(5):744–8.

Sundel MH, Newland JJ, Blackburn KW, Vesselinov RM, Eisenstein S, Bafford AC. Sex-Based Differences in IBD Surgical Outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2024;67(2):246–53.

Khalili H, Everhov ÅH, Halfvarson J, Ludvigsson JF, Askling J, Myrelid P, et al. Healthcare use, work loss and total costs in incident and prevalent Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from a nationwide study in Sweden. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(4):655–68.

Lin KK, Sewell JL. The effects of race and socioeconomic status on immunomodulator and anti-tumor necrosis factor use among ambulatory patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(12):1824–30.

Mahlich J, Matsuoka K, Sruamsiri R. Biologic treatment of Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):160.

Rundquist S, Eriksson C, Nilsson L, Angelison L, Jaghult S, Bjork J, et al. Clinical effectiveness of golimumab in Crohn’s disease: an observational study based on the Swedish National Quality Registry for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(10–11):1257–63.

Schultheiss JPD, Brand EC, Lamers E, van den Berg WCM, van Schaik FDM, Oldenburg B, et al. Earlier discontinuation of TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy in female patients with inflammatory bowel disease is related to a greater risk of side effects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(4):386–96.

Tanaka H, Kamata N, Yamada A, Endo K, Fujii T, Yoshino T, et al. Long-term retention of adalimumab treatment and associated prognostic factors for 1189 patients with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Australia). 2018;33(5):1031–8.

Lagana B, Zullo A, Scribano ML, Chimenti MS, Migliore A, Diamanti AP, et al. Sex differences in response to TNF-Inhibiting drugs in patients with spondyloarthropathies or inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2019;9(JAN):47.

Calvo-Arbeloa M, Insausti-Serrano AM, Arrondo-Velasco A, Sarobe-Carricas MT. Adherence to treatment with adalimumab, golimumab and ustekinumab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Adherencia al tratamiento con adalimumab, golimumab y ustekinumab en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. 2020;44(2):62–7.

Sprakes MB, Ford AC, Warren L, Greer D, Hamlin J. Efficacy, tolerability, and predictors of response to infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease: a large single centre experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(2):143–53.

Eriksson C, Marsal J, Bergemalm D, Vigren L, Björk J, Eberhardson M, et al. Long-term effectiveness of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease: a national study based on the Swedish National Quality Registry for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(6–7):722–9.

Shah SC, Khalili H, Gower-Rousseau C, Olen O, Benchimol EI, Lynge E, et al. Sex-based differences in incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases—pooled analysis of population-based studies From Western Countries. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1079-89.e3.

Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Ananthakrishnan AN, Richter JM, Feskanich D, Fuchs CS, et al. Oral contraceptives, reproductive factors and risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62(8):1153–9.

Khalili H, Granath F, Smedby KE, Ekbom A, Neovius M, Chan AT, et al. Association between long-term oral contraceptive use and risk of crohn’s disease complications in a nationwide study. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1561-7.e1.

Ortizo R, Lee SY, Nguyen ET, Jamal MM, Bechtold MM, Nguyen DL. Exposure to oral contraceptives increases the risk for development of inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis of case-controlled and cohort studies. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(9):1064–70.

Langen MLV, Hotte N, Dieleman LA, Albert E, Mulder C, Madsen KL. Estrogen receptor-β signaling modulates epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300(4):G621–6.

Vieujean S, De Vos M, D’Amico F, Paridaens K, Daftary G, Dudkowiak R, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease meets fertility: A physician and patient survey. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55(7):888–98.

Nahon S, Lahmek P, Saas C, Durance C, Olympie A, Lesgourgues B, et al. Socioeconomic and psychological factors associated with nonadherence to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease patients: results of the ISSEO survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(6):1270–6.

Frølich A, Ghith N, Schiøtz M, Jacobsen R, Stockmarr A. Multimorbidity, healthcare utilization and socioeconomic status: A register-based study in Denmark. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8): e0214183.

Yong J, Yang O. Does socioeconomic status affect hospital utilization and health outcomes of chronic disease patients? Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(2):329–39.

Agerholm J, Bruce D, Ponce De Leon A, Burström B. Socioeconomic differences in healthcare utilization, with and without adjustment for need: An example from Stockholm, Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(3):318–25.

Lemstra M, Mackenbach J, Neudorf C, Nannapaneni U. High Health Care Utilization and Costs Associated with Lower Socio-economic Status: Results from a Linked Dataset. Can J Public Health. 2009;100(3):180–3.

Van Der Heide I, Wang J, Droomers M, Spreeuwenberg P, Rademakers J, Uiters E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the dutch adult literacy and life skills survey. J Health Commun. 2013;18(sup1):172–84.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Southern Denmark Nathalie Fogh Rasmussen was financially supported by Hospital Sønderjylland, the University Hospital of Southern Denmark, the Research Unit of Molecular Diagnostic and Clinical Research, and the study was further supported by the Danish Beckett-Fonden (grant no. 20–2-6128) and the Danish Knud and Edith Eriksens Mindefond. TJ is supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF148).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NFR, CM, LKG, and ZH designed the search template and did the search and data collection in detail. The data analysis was done by NFR, CM, SRP, and AP, the bias assessment by NFR and CM, the meta-analysis by NFR, SRP, and AP, the funnel plot by AP, and the certainty assessment by NFR and CM. All authors contributed to manuscript development. NFR, CM, AG, TJ, and LJK participated in the critical scrutiny and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

TJ reports consulting for Ferring and Pfizer. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

13643_2024_2584_MOESM5_ESM.docx

Additional file 5: Figure A1. Meta-regression of log HRs for risk of surgery by study publication year. Figure A2. Meta-regression of log ORs for risk of hospitalization by study publication year. Figure A3. Forest plot of subgroup (univariate/multivariate) meta-analysis of HRs for risk of surgery. Figure A4. Forest plot of subgroup (univariate/multivariate) meta-analysis of ORs for risk of hospitalization. Figure A5. Funnel plot of the meta-analysis of published studies on surgery. Figure A6. Funnel plot of the meta-analysis of published studies on hospitalization.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasmussen, N.F., Moos, C., Gregersen, L.H.K. et al. Impact of sex and socioeconomic status on the likelihood of surgery, hospitalization, and use of medications in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 13, 164 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02584-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02584-3