Abstract

Background

Delirium commonly occurs in hospitalized adults. Psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can co-occur with delirium, and can be recognized and managed by clinicians using recommendations found in methodological guiding statements called Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs). The specific aims of this review were to: [1] synthesize CPG recommendations for the diagnosis and management of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in adults with delirium in acute care; and [2] identify recent published literature in addition to those identified and reported in a 2017 review on delirium CPG recommendations and quality.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and 21 sites on the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies listed in the Health Grey Matters Lite tool were searched from inception to February 12, 2021. Selected CPGs focused on delirium in acute care, were endorsed by an international scientific society or governmental organization, and contained at least one recommendation for the diagnosis or management of delirium. Two reviewers independently extracted data in duplicate and independently assessed CPG quality using the AGREE-II tool. Narrative synthesis of CPG recommendations was conducted.

Results

Title and abstract screening was completed on 7611 records. Full-text review was performed on 197 CPGs. The final review included 27 CPGs of which 7 (26%) provided recommendations for anxiety (4/7, 57%), depression (5/7, 71%), and PTSD (1/7, 14%) in delirium. Twenty CPGs provided recommendations for delirium only (e.g., assess patient regularly, avoid use of benzodiazepines). Recommendations for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders with delirium included using evidence-based diagnostic criteria and standardized screening tools. Recommendations for the management of psychiatric disorders with delirium included pharmacological (e.g., anxiolytics, antidepressants) and non-pharmacological interventions (e.g., promoting patient orientation using clocks). Guideline quality varied: the lowest was Applicability (mean = 36%); the highest Clarity of Presentation (mean = 76%).

Conclusions

There are few available evidence-based CPGs to facilitate appropriate diagnosis and management of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in patients with delirium in acute care. Future guideline developers should incorporate evidence-based recommendations on the diagnosis and management of these psychiatric disorders in delirium.

Systematic review registration

Registration number: PROSPERO (CRD42021237056)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Delirium is an acute and complex neuropsychiatric disorder that commonly affects hospitalized patients [1]. Delirium is the most common neuropsychiatric disorder in acute care, with prevalence estimates of 10–30% within the hospitalized population [2, 3]. Patients with delirium are often hospitalized for longer and have a poorer survival prognosis than those without delirium, and the risk of developing delirium generally increases with the severity of illness [4]. Identifying and implementing effective strategies to mitigate the risk of delirium are essential to reducing long-term morbidity related to critical illness [5].

Delirium and other neuropsychiatric disorders are often similar in presentation, often present concurrently, and patients may have more than one type of disorder [6]. There is difficulty distinguishing these disorders: for example, severe hypoactive delirium [7] can be confused with depression, and hyperactive delirium [8] can be confused with mania. Patients should be evaluated for delirium and psychiatric disorders to not to miss important medical problems; a lack of recognition for pre-existing and new psychiatric disorders during an acute care admission may contribute to poor patient mental health and increased severity of psychiatric disorder symptoms [9,10,11].

A Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) is a methodological statement aimed at providing guidance to clinicians and their patients for specific medical circumstances and conditions [12]. CPG use can support the reduction of financial cost from inappropriate care and can improve clinical decision-making and quality of care for clinicians and patients [13]. A recent systematic review of the quality of CPGs for delirium in acute care evaluated the quality of guideline recommendations focusing on knowledge translation resources and the practical application and monitoring of guideline implementation [14]. The most recent included CPG in this review was published in 2013 thereby necessitating an updated review to identify progress and/or gaps in our evidence base on this topic.

The first objective of our systematic review is to add an analysis, synthesis, and quality assessment of the available CPGs on recommendations for the identification and management of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in adults with delirium in acute care. The second objective is to provide an updated synthesis and quality assessment of CPG recommendations for delirium identification and management in acute care.

Methods

This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021237056) prior to data abstraction and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [15] (Additional file 1: Appendix 1).

Identification and selection of studies

We performed systematic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL from inception to February 12, 2021, to identify eligible CPGs. We additionally performed a comprehensive search of the grey literature using the 21 sites listed on the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Grey Matters Lite tool [16] from inception to February 12, 2021. Search strategies for each database are included in Additional file 2: Appendix 2. A librarian (N.D.) performed an independent PRESS review [17] of the EMBASE search strategy. CPG reference lists were screened for additional guidelines relevant to the review which may have been missed by the search. No limits (e.g., date, language) were applied to any search.

Study eligibility

Two reviewers (T.G.P., S.J.M.) assessed record title and abstract eligibility independently and in duplicate. Guidelines eligible for inclusion were written in English, were issued or endorsed by a national or international scientific society or government organization and had a primary focus on the diagnosis and/or management of delirium in any acute care setting. Guidelines eligible for inclusion contained at least one recommendation on the diagnosis, prevention, or management of delirium presented within guideline text, tables, figures, algorithms, and/or decisions paths. Guideline recommendation(s) on delirium must: (1) be accompanied with an explicit level of confidence (i.e., the GRADE system [18]); and (2) explicitly discuss one or more interventions for the recognition or management of delirium. Comparison of these recommended interventions to other interventions was not required. Guidelines with additional recommendations pertaining to anxiety, depression, or PTSD were of special interest. Any year of publication, publishing region and guideline development process were of interest. The most updated versions of guidelines were included in the review. Title and abstracts were advanced for full-text review if both reviewers agreed independently and in duplicate that they satisfied one or more of the eligibility criteria. Full-text guidelines were included in the review if both reviewers agreed independently and in duplicate that they met all the criteria for inclusion. Discrepancies were handled through discussion with a third reviewer (K.D.K.).

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was completed independently and in duplicate by two reviewers (T.G.P. and S.J.M.). Data extracted from included guidelines consisted of guideline name, author(s), development group, country, language(s), target population(s), evidence consensus method(s) and psychiatric disorder(s). Narrative synthesis of recommendations for diagnosis and management of delirium and of psychiatric disorders was completed after data extraction for relevant guidelines. Recommendations for diagnosis and management of any symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in delirium were included, in addition to recommendations for the management of pre-existing or new diagnoses of these disorders.

Guideline quality assessment using AGREE II

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) Instrument [19] is designed to assess the methodological quality and reporting foundation of a CPG. The AGREE II tool is composed of a total of 23 items in 6 Domains and 2 overall global rating items. All items are rated on a seven-point scale (1 = no information or poorly reported, 7 = reporting quality is exceptional and meets all criteria); except for the second global rating item which asks if the rater would recommend the guideline for use (yes, yes with modification, or no). The six Domains include: Domain 1, Scope and Purpose (assesses the overall guideline goal and target population as well as the health questions); Domain 2, Stakeholder Involvement (targets the participants involved in the guideline development group and how the guideline represents the perspectives of users); Domain 3, Rigor of Development (assesses how the evidence was gathered, expressed, and how it will be updated); Domain 4, Clarity of Presentation (reviews guideline organization and language); Domain 5, Applicability (assesses if implementation is feasible, the economic consequences, and if there are specific strategies for implementation); and Domain 6, Editorial Independence (measures the level of independence from funding institutions and competing interests of guideline developers). Two reviewers (T.G.P. and S.J.M.) scored all included guidelines independently and in duplicate, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. As suggested by the AGREE II tool [19], six scaled Domain scores for each guideline were calculated by summing all individual scores in the Domain and scaling as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that Domain. For each guideline, the average overall score was determined by taking the mean of the first overall global rating item (“Rate the overall quality of this guideline from 1 to 7”) after both reviewers assigned it a score. For the overall assessment, reviewers used criteria from all Domains to judge if they would recommend the guideline for use using “yes”, “yes, with modification”, or “no”.

Results

Results of search

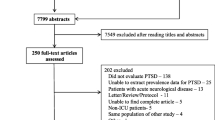

Initial database search, grey literature search and reference list screening resulted in a total of 10,774 records (Fig. 1). After duplicates were removed, 7611 records were screened by title and abstract, and 7314 were excluded. Full-text review was performed on 197 records and following this, 170 records were excluded due to: not being a full guideline (e.g., not providing specific sections such as references) (n = 149), not being endorsed by a national or international scientific society or government organization (n = 12), not available in English (n = 2), not focused on delirium (n = 2), full-text unavailable (n = 1), and being a duplicate (n = 4). The final review included 27 CPGs.

Study characteristics

Guideline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Included guidelines were published from 1999 to 2020, with two guidelines being updates of previous versions: Jacobi et al. published in 2002, updated from 1994 [20], and Devlin et al. published in 2018, updated from 2013 [21]. The most recent versions of guidelines were included in the review. Countries where guidelines were developed included Canada (n = 10), United States of America (n = 7), United Kingdom (n = 7), Australia (n = 1), Europe (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), India (n = 1), and Switzerland (n = 1). The most common guideline target populations were healthcare professionals working in general (e.g., general hospital) acute care settings (n = 12; 44%) and ICU healthcare professionals (n = 4; 15%). Informal consensus (i.e., discussion) was the most commonly used consensus method during guideline development (n = 12; 44%), however, this was often employed alongside formal tools such as GRADE [18], AGREE [19], or the development method and guideline classification schemes described by Shekelle et al. [22]. While all (n = 27) guidelines focused on delirium, 20 guidelines (74%) included recommendations on delirium only, whereas seven guideline (26%) provided additional recommendations for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in delirium.

Quality of included guidelines

Individual and cumulative guideline Domain scores assessed by the AGREE II tool are presented in Table 2. The lowest cumulative Domain was Domain 6, Editorial Independence, with a mode of 4% and a range of 4–92%. The highest cumulative Domain was Domain 4, Clarity of Presentation, with a mode of 92% and a range of 47–100%. The guideline by McNeill et al. [23] scored the highest in all Domains compared to all other guidelines: Domains 1–4 and 6 scored 92% while Domain 5 scored 71%. In addition, this guideline received an overall score of 6, and both reviewers recommended the guideline for use.

Summary of recommendations for delirium

A synthesis of recommendations for delirium stratified by recognition and prevention is presented in Table 3. Specific sub-populations more at risk for delirium were mentioned in fewer than 60% of included guidelines: approximately half (n = 14; 52%) of included guidelines were designed to recognize and prevent post-operative delirium; recommendations specific to older adults (defined as > 65 years of age) were presented in 15 guidelines (56%).

Recommended delirium assessment tools included the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) [24], Confusion Assessment Method-Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) [25], the 4 “A”s Test (4AT) [26, 27], and the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) [28]. Approximately half (n = 14; 52%) of included guidelines explicitly recommended using validated tools for delirium assessment. The most common diagnostic criteria for delirium was the fourth or fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV or DSM-5), mentioned in 11 guidelines (41%). General recommendations for the recognition of delirium included training for healthcare professionals to increase awareness of delirium and delirium treatment options [29,30,31]. One guideline recommended referring patients with delirium to a trained mental health professional for further evaluation [32].

Recommendations for delirium prevention included pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions once reversible medical causes of delirium (e.g., infection, pain) were addressed. Non-pharmacological interventions promoted patient orientation (i.e., using clocks, using a calendar, avoiding unnecessary room changes); social contact (i.e., friend and family visits); and comfort (i.e., avoiding unnecessary catheterization, monitoring nutrition and hydration, ensuring working hearing and visual aids) [23]. Adequate analgesia was recommended using a non-opioid medication first, and if an opioid was needed the minimum effective dose was recommended [29] with an opioid rotation in place [30]. Physical restraint was only recommended in exceptional circumstances, when a patient was a risk to themselves or others [33], and a restraint protocol should be used and routinely re-evaluated [34]. Pharmacological management for delirium most commonly included treatment with a benzodiazepine, a first, second, or third-generation antipsychotic [35], or a cholinergic drug [36]. Cancer therapy and medications exacerbating delirium (e.g., benzodiazepines, phenytoin) [33, 35] were recommended to be deprescribed. One guideline provided recommendations for imaging new onset (i.e., incident) delirium using a computed tomography (CT) head scan without contrast. Further evaluation of delirium with suspected brain abnormalities can be performed with contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging [37].

Summary of recommendations for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in delirium

A synthesis of recommendations for guidelines that report on anxiety, depression and PTSD in delirium is presented in Table 4. Two out of the seven guidelines (29%) [23, 38] provided recommendations specific to older adults > 65 years of age.

Four out of the seven guidelines (57%) provided recommendations specific to the management and prevention of anxiety in delirium. Andersen et al. [32] recommended screening based on validated tools such as the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [39], Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) [40], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [41], or Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [42]. Non-pharmacological interventions were recommended for management of environmental and medical causes of anxiety [43]; however, no specific interventions were recommended. Pharmacological recommendations included the use of a benzodiazepine [43], while minimizing anxiolytics until delirium has resolved to limit delirium aggravation [36]. General treatment considerations included treating reversible medical causes of symptoms first [32], and treating delirium first over other psychiatric disorders [36]. Jacobi et al. indicated that pharmacological sedation should only be used after reversible medical causes were treated and analgesia was provided [20]. Andersen et al. recommended different treatment pathways based on the severity of symptoms of anxiety (e.g., mild symptomatology may require referral to supportive care services while severe symptomatology may require high intensity psychological and pharmacological intervention) [32].

Five out of the seven guidelines (71%) provided recommendations specific to the recognition and management of depression in delirium. Risk factors for depression included patient factors (i.e., cognitive decline or dementia, social isolation, personal or family history of depression or mood disorder) [23] and previous use of certain medications (i.e., antihypertensives, antimicrobials, and analgesics) [38]. Tools recommended for depression screening included the Sig: E. Caps [44], Cornell Scale for Depression [45], and Geriatric Depression Scale [46]. A variety of non-pharmacological interventions for depression were presented and these included: psychotherapy, exercise, electroconvulsive therapy, aromatherapy, and light therapy [23, 38]. All five guidelines mentioned pharmacological interventions and these included antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and tricyclic antidepressants; however, selection was recommended to be based on a medication with the fewest drug interactions [47] and with limited duration of therapy during delirium [36] as it may worsen delirium symptoms. General treatment considerations included first treating reversible medical causes, differentiating psychiatric symptoms from normal grieving process for those with cancer or advanced disease, and referring patients with a risk of suicide for an in-depth assessment with a mental health specialist [23]. One guideline recommended that an individualized treatment plan should be developed based on levels of depression severity, and the patient should be monitored for changes in behavior and followed-up every two weeks after intervention [32].

A single guideline out of the seven (14%) provided a recommendation specific to PTSD in delirium, and referred to using pharmacological sedation for agitation only after treating reversible medical causes of symptoms and providing adequate analgesia [20].

Discussion

In this systematic review, we provide an updated synthesis of CPGs for the diagnosis and management of delirium in patients admitted to an acute care setting. This review also provides a new analysis of CPGs with recommendations for the diagnosis and management of anxiety, depression, or PTSD in adults with delirium in acute care. Recommendations for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in delirium included screening with tools and assessment of risk factors, while recommendations for the management of psychiatric disorders in delirium included treating reversible medical causes first, utilizing non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions, and monitoring the patient for changes in cognition. This review highlights the lack of published CPGs for healthcare professionals to recognize and prevent psychiatric disorders in adults with delirium using evidence-based practice.

Recommendations, if present, were often vague (e.g., recommending pharmacological agents without specifying by type or name of drug, lack of specific diagnosis criteria or flowcharts). This may be due to the lack of studies with a low risk of bias (i.e., randomized controlled trials [RCTs]) being performed on the prevention and treatment of psychiatric disorders in adults with delirium in acute care; or a deficit in updating guidelines to reflect current evidence-based practice. Clinical practice is altered constantly as new information is acquired, and new studies are performed [48]. In this review, 70% of included guidelines were published before 2019, and many have no explicit update information or criteria (AGREE II Domain 3, item 14). Up to date clinical practice guidelines are needed to ensure current evidence-based practice and better patient outcomes. Ideally, guideline developers should strive to improve not only the CPG update procedure and search terms used for evidence acquisition described in the AGREE II Domain 3, Rigour of Development but all AGREE II Domains with the lowest scores: Domain 5, Applicability; and Domain 6, Editorial Independence. Guideline developers should ensure that financial implications of guideline implementation have been considered and that clear auditing criteria are described to satisfy the Applicability Domain. Lastly, for the Editorial Independence Domain, the reporting of guideline developers’ competing interests and explicit funding statements should be included.

Healthcare professionals have reported feeling underprepared when dealing with patients with psychiatric disorders in the ICU [49] and may benefit from CPG recommendations to guide patient care. Some guidelines presented screening tools to facilitate the recognition of psychiatric disorders in delirium. Early identification of psychiatric disorders in delirium using standardized screening tools is important in the implementation of preventative interventions [50], which could contribute to a lowered psychological burden [51]. For the prevention of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in delirium, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions were discussed. Non-pharmacological interventions (i.e., music therapy, mind-body interventions by family members or healthcare professionals, counselling) have been previously used in the ICU to reduce ICU-related distress without the need for sedative drugs [52]. Pharmacological interventions for anxiety or depression should be carefully assessed, as antidepressants and benzodiazepines are linked to worsened delirium [53, 54]. In response, guidelines recommended waiting until delirium has resolved to prescribe pharmacological interventions for anxiety or depression [36].

Our work aimed to update a 2017 systematic review on the quality of CPGs for use in the treatment of delirium within acute care [14]. Similarly, to this review, we identified many guidelines not kept up to date, as well as CPGs that achieved low AGREE scores in the domains of Applicability and Editorial Independence. However, our review reveals newfound differences in guideline target users as well as patient population, such that CPGs identified in our review were targeted to groups other than healthcare professionals (e.g., family caregivers, health system leaders, and policy makers). In addition, we found a higher proportion of CPGs that included recommendations for the general hospitalized population. This may represent the increased knowledge and recognition of delirium among members of the clinical care team (apart from healthcare professionals) in the acute care setting over the last 10 years.

The information provided in this systematic review must be taken in the context of relevant limitations. Most guidelines included in this review originated from Canada, the United States of America, or the United Kingdom, and were written primarily in English. Approaches to delirium recognition and treatment, in addition to the use of protocols for the management of delirium, are known to vary across countries [55]; guidelines included in our study may under-represent perspectives from other countries. While most clinicians understand CPGs to be helpful tools, their use in practice may be limited by the inflexibility of certain recommendations in specialized or unusual cases [56]. As well, to ensure reliability, two authors completed study screening, data extraction, and guideline quality assessment independently and in duplicate. Considering that reliability statistics in systematic reviews are sensitive to 'true prevalence' in the data—if the true prevalence of a population is high or low, agreement expected by chance increases and the magnitude of kappa goes down—reliability statistics were not conducted. Additionally, guidelines that were excluded from this review in the full-text stage due to lack of endorsement or availability of full-text may have provided additional recommendations that were missed.

This synthesis of guideline recommendations for delirium and for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in delirium provides a succinct guide for healthcare professionals. Based on the existing literature, current recommendations for the diagnosis and management of delirium and of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in delirium are minimal, but may help inform patient care. More recommendations for the diagnosis and management of psychiatric disorders in delirium are needed, and the conduct of RCTs for interventions of interest could facilitate higher quality evidence-based recommendations.

Conclusion

The evidence base is minimal for clinical practice guidelines that report on the diagnosis and management of symptoms of possible psychiatric disorders in adult patients with delirium in the acute care setting. Patients with delirium that display symptoms of psychiatric disorders may require specific evaluation during their hospitalization to ensure that psychiatric disorders are identified, and management plans are developed for this patient population in the follow-up period.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- AGREE:

-

Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument

- BAI:

-

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- CADTH:

-

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- CAM:

-

Confusion Assessment Method

- CAM-ICU:

-

Confusion Assessment Method Intensive Care Unit

- CPG:

-

Clinical Practice Guideline

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GAD:

-

General anxiety disorder

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- ICDSC:

-

Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses

- PTSD:

-

Post traumatic stress disorder

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- STAI:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

References

Hosie A, Davidson PM, Agar M, Sanderson CR, Phillips J. Delirium prevalence, incidence, and implications for screening in specialist palliative care inpatient settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27(6):486–98.

Maldonado JR. Delirium in the acute care setting: characteristics, diagnosis and treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(4):657–722 (vii).

Minden SL, Carbone LA, Barsky A, Borus JF, Fife A, Fricchione GL, et al. Predictors and outcomes of delirium. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(3):209–14.

Misra S, Ganzini L. Delirium, depression, and anxiety. Crit Care Clin. 2003;19(4):771–87 (viii).

Hsieh SJ, Ely EW, Gong MN. Can intensive care unit delirium be prevented and reduced? Lessons learned and future directions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(6):648–56.

Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. New England J Med. 2017;377(15):1456–66.

Lipowski ZJ. Transient cognitive disorders (delirium, acute confusional states) in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(11):1426–36.

Meagher D. Motor subtypes of delirium: past, present and future. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(1):59–73.

Dorman-Ilan S, Hertz-Palmor N, Brand-Gothelf A, Hasson-Ohayon I, Matalon N, Gross R, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in COVID-19 isolated patients and in their relatives. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:581598.

Nelson R. No-visitor policies cause anxiety and distress for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(12):e554.

Samrah SM, Al-Mistarehi AH, Aleshawi AJ, Khasawneh AG, Momany SM, Momany BS, et al. Depression and coping among COVID-19-infected individuals after 10 days of mandatory in-hospital quarantine, Irbid Jordan. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:823–30.

In: Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington (DC)1990.

Lohr KN. Guidelines for clinical practice: applications for primary care. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994;6(1):17–25.

Bush SH, Marchington KL, Agar M, Davis DH, Sikora L, Tsang TW. Quality of clinical practice guidelines in delirium: a systematic appraisal. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e013809.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

CADTH. Grey matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. 2018. Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence .

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-42.

Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, Riker RR, Fontaine D, Wittbrodt ET, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):119–41.

Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):e825–73.

Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7183):593–6.

McNeill S, White V, An D, Legere L, Rey M, Toor GK, et al. Delirium, dementia, and depression in older adults: assessment and care, second edition. 2 ed: Registered Nurses Association of Ontario; 2016. p. 37-80.

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–8.

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–10.

The 4 "A"s Test. Available from: http://www.the4at.com/.

Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DH, Mazzola P, Turco R, Gentile S, et al. Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43(4):496–502.

Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(5):859–64.

Allard P, Braijtman S, Bruto V, Burne D, Gage L, Gagnon PR, et al. Guideline on the assessment and treatment of delirium in older adults at the end of life: Canadian Coalition for Seniors' Mental Health. Toronto; 2010.

Brajtman S, Wright D, Hogan DB, Allard P, Bruto V, Burne D, et al. Developing guidelines on the assessment and treatment of delirium in older adults at the end of life. Can Geriatr J. 2011;14(2):40–50.

Potter J, George J, Guideline Development G. The prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people: concise guidelines. Clin Med (Lond). 2006;6(3):303–8.

Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, Gruman J, Champion VL, Massie MJ, et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1605–19.

Hogan DB, Gage L, Bruto V, Burne D, Chan P, Sadowski CA, et al. National guidelines for seniors’ mental health: The assessment and treatment of delirium. Canadian Journal of Geriatrics. 2006;9:S42–51.

Michaud L, Bula C, Berney A, Camus V, Voellinger R, Stiefel F, et al. Delirium: guidelines for general hospitals. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):371–83.

Bush SH, Lawlor PG, Ryan K, Centeno C, Lucchesi M, Kanji S, et al. Delirium in adult cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv143–65.

Trzepacz P, Breitbart W, Franklin J, Levenson J, Martini DR, Wang P. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 Suppl):1–20.

Expert Panel on Neurological I, Luttrull MD, Boulter DJ, Kirsch CFE, Aulino JM, Broder JS, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria acute mental status change, delirium, and new onset psychosis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(5S):S26–37.

Virani T, Santos J, McConnel H, Schouten JM, Lappan-Gracon S, Scott C, et al. Caregiving strategies for older adults with delirium, dementia, and depression: Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. Ontario; 2004. p. 36.

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–7.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Group NRGD. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing symptoms (including at the end of life) in the community. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2020. Copyright © NICE 2020.

Jenike MA. Geriatric psychiatry and psychopharmacology: a clinical approach. Chicago, IL: Yearbook Medical Publishing; 1989.

Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23(3):271–84.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49.

Comittee BGaPA. Palliative care for the patient with incurable cancer or advanced disease part 2: Pain and symptom management. Victoria: BCGuidelines.ca; 2017.

Gupta DM, Boland RJ Jr, Aron DC. The physician’s experience of changing clinical practice: a struggle to unlearn. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):28.

Weare R, Green C, Olasoji M, Plummer V. ICU nurses feel unprepared to care for patients with mental illness: a survey of nurses’ attitudes, knowledge, and skills. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;53:37–42.

Peris A, Bonizzoli M, Iozzelli D, Migliaccio ML, Zagli G, Bacchereti A, et al. Early intra-intensive care unit psychological intervention promotes recovery from post traumatic stress disorders, anxiety and depression symptoms in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R41.

Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, Puelle M, Dowal S, Travison T, et al. Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):512–20.

Wade DF, Moon Z, Windgassen SS, Harrison AM, Morris L, Weinman JA. Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce ICU-related psychological distress: a systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016;82(4):465–78.

Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2004;80(945):388–93.

Foy A, O’Connell D, Henry D, Kelly J, Cocking S, Halliday J. Benzodiazepine use as a cause of cognitive impairment in elderly hospital inpatients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(2):M99-106.

Morandi A, Piva S, Ely EW, Myatra SN, Salluh JIF, Amare D, et al. Worldwide Survey of the “Assessing Pain, Both Spontaneous Awakening and Breathing Trials, Choice of Drugs, Delirium Monitoring/Management, Early Exercise/Mobility, and Family Empowerment” (ABCDEF) Bundle. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):e1111–22.

Farquhar CM, Kofa EW, Slutsky JR. Clinicians’ attitudes to clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2002;177(9):502–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Alberta Health Services Critical Care Strategic Clinical Network (CC SCN). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the CC SCN Scientific Office or Alberta Health Services. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All those designated as authors (TGP, NJ, KMF, HTS, SJM) have met all ICMJE criteria for authorship: substantial contributions to the conception OR design of the work; OR the acquisition, analysis, OR interpretation of data; OR the creation of new software used in the work; OR have drafted the work or substantively revised it; AND approved the submitted version (and any substantially modified version that involves the author’s contribution to the study); AND agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. TGP was involved in the concept and design, acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. NJ was involved in drafting of the manuscript. HTS was involved in administrative, technical, or material support. KMF was involved in the concept and design and administrative, technical, or material support. SJM was involved in the concept and design, acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and administrative, 50 technical, or material support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Appendix 1. PRISMA 2020 checklist. Table containing the PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Additional file 2:

Appendix 2. Database and grey literature search strategies. List of all search strategies used for MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases, and a grey literature search tool.

Additional file 3:

Appendix 3. Footnotes of Table 3: Synthesis of recommendations for delirium. Contains footnotes of Table 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Poulin, T.G., Jaworska, N., Stelfox, H.T. et al. Clinical practice guideline recommendations for diagnosis and management of anxiety and depression in hospitalized adults with delirium: a systematic review. Syst Rev 12, 174 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02339-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02339-6