Abstract

Background

Approximately 14% of Africans infected with HIV are over the age of 50, yet few intervention studies focus on improving access to care, retention in care, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in this population. A review of the published literature until 2012, found no relevant ART management and care interventions for older people living with HIV (OPLHIV) in sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of this systematic review is to update the original systematic review of intervention studies on OPLHIV, with a focus on evidence from sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the available published literature from 2012 to 2017 to explore behavioral and cognitive interventions addressing access to ART, retention in HIV care and adherence to ART in sub-Saharan Africa that include older adults (50+). We searched three databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Education Resources Information Center) using relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms as well as a manual search of the reference lists. No language restrictions were placed. We identified eight articles which were analyzed using content analysis with additional information obtained directly from the corresponding authors.

Results and discussion

There were no studies that exclusively focused on OPLHIV. Three studies referred only to participants being over 18 years and did not specify age categories. Therefore, it is unclear whether these studies actively considered people living with HIV over the age of 50. Although the studies sampled older adults, they lacked sufficient data to draw conclusions about the relevance of the outcomes of this group.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the need to increase the evidence-base of which interventions will work for older Africans on ART.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2015, an estimated 25.5 million people were living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The global HIV epidemic shows a growing number of people aged 50 years and older who are living with HIV [2,3,4]. According to a report by UNAIDS [5], 9% of the people living with HIV (PLHIV) in sub-Saharan Africa were over the age of 50 in 2012.

The increasing proportion of older people living with HIV (OPLHIV) is related to three main factors: (1) the success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in prolonging the lives of PLHIV; (2) decreasing HIV incidence among younger adults, which shifts the disease burden to older ages; and (3) the fact that people aged 50 years and older exhibit similar risky behaviors as younger people [5]. Although the increasing numbers of PLHIV over 50 years has important implications for HIV responses, very few HIV strategies in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) explicitly focus on this previously hidden population [5,6,7].

An exploration of the factors affecting the general health-seeking behaviors of the 50+ age group in sub-Saharan Africa shows several barriers. Some of these barriers to health care include lack of money for transport and care services, unkind treatment by health workers and health staff who have few resources and little understanding of older persons’ needs [8,9,10]. Because of the increased vulnerability of older people seeking health care services within the health systems of LMIC in general, these barriers are possibly exacerbated for those who are experiencing any sort of ill-health [10].

The barriers to access to care and treatment services experienced within the general older population, including those who are unwell, are potentially compounded among those who are HIV-positive. For example, because of cultural norms around respect for older persons and against intergenerational discussions of sex and sexuality, older persons may be reluctant to honestly discuss their symptoms and diagnosis with younger health care staff [8, 11]. In addition, older adults who live with HIV are more likely to have co-morbidities, resulting from the aging process and/or because of their HIV infection [12, 13].

Evidence suggests that OPLHIV may have greater access to health services than those without HIV [14,15,16]. This is because, the presence of both HIV and non-communicable diseases makes it particularly important to pay attention to the effect of concurrent health conditions. Consequently, emphasis is laid on access to care and treatment adherence in this population. This phenomenon is described as the ART advantage [17].

There are also emerging data from high-income countries that older adults’ access and adherence to ART are distinct [18]. Although it appears that adherence is better among older populations [19], cognitive impairment can reduce adherence and treatment outcomes [20]. Regardless of this, the preponderance of research around the factors affecting adherence and access to care and related interventions in sub-Saharan Africa to address these problems focus exclusively on adults under 50 years of age [7, 21,22,23,24,25,26]. It is, therefore, necessary to consider the development of context-specific interventions to address the specific needs of older Africans living with HIV.

Despite the clear need, there have been a limited number of intervention studies that aim to improve access to care and ART adherence among OPLHIV [20]. A review published in 2014 of the literature on ART care and adherence published up until 2012 found no relevant interventions for OPLHIV in Africa [7]. The evidence for interventions in high income countries is relatively limited with three reviews published in 2014 identifying only a handful of interventions directly addressing access to ART or adherence and as noted by Negin et al. [7] even these have many limitations [7, 27, 28]. Although not within the scope of this review, a search of the literature after 2014 suggests that this pattern has continued with only a few relevant publications on interventions about OPLHIV from high income countries found [29,30,31]. There is, therefore, a dearth of evidence for interventions that address the needs of OPLHIV in Africa especially within sub-Saharan Africa where almost 10% of PLHIV are those over 50 years [32].

To this end, we sought to update the original systematic review of intervention studies published by Negin et al. [7] with a focus on evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. We explored whether, in the recent upturn in research into OPLHIV [3, 33,34,35], there has been an increase in evidence for effective behavioral and cognitive interventions to address older Africans’ access to care and adherence to ART. Since evidence suggests no specific ART behavioral and cognitive interventions in sub-Saharan Africa exclusively focuses on older adults, we also explored interventions in sub-Saharan Africa that include older adults to assess insights into which types of interventions might benefit OPLHIV.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review with a content analysis approach of the published literature from 2012 to present in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Education Resources Information Center. We supplemented the search of these databases with a reference chase of the identified articles. Because this is an update of a previously conducted systematic review, we did not register it in PROSPERO.

Selection of studies

The following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and combinations were used to search the identified databases [antiretroviral therapy/agents, Anti-HIV Agents, Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy, medication adherence/adherence, Patient Compliance/or Medication Adherence/“Patient Acceptance of Health Care,” “middle aged (45 plus years),” (aging or seniors or older), Texting or Text Messaging/Motivational Interviewing/or Counseling/Behavior Therapy/or behavioral intervention, Patient Education]. We also conducted a manual search of the reference lists of the articles identified from the databases to complement the electronic search. We defined a search strategy to retrieve from the databases and to manually search, papers that were peer-reviewed, from sub-Saharan Africa, that assesses behavioral or cognitive interventions to address challenges of access to care, treatment, adherence to ART, and retention in care among older adults (50+). No language restrictions, which is in line with Negin et al. [7]. The inclusion/exclusion of the identified articles was guided by the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Time (PICOT) mnemonics (Table 1).

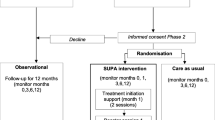

Only papers that reported outcomes related to access to care, treatment adherence, and retention in care interventions conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, and including older adults were selected for the final review (Fig. 1). Our timeline started from 2012 to 2017 because the review conducted by Negin et al. [7] covered the previous years. Our search was meant, therefore, to complement what had been previously done by Negin et al. [7]. Data from relevant articles were extracted into an excel spreadsheet.

The NIH-NHLBI Quality Assessment of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses were used to rate (good, fair, and poor) the quality of studies (Table 2) [36]. Six of the eight articles were rated as ‘good’ and the remaining two were rated ‘fair’.

Thematic analysis was used to identify major themes in the chosen studies. We followed the PRISMA guidelines to report the study.

Data collection

The extraction of the data was conducted by FCM and LK. ES checked the extraction and resolved any ‘disagreements’ that emanated from the extraction process. Extraction of data from the identified papers was done under the following topics: (1) study citation and setting, (2) intervention type, (3) focus of intervention, (4) study design, (5) outcome measures, (6) study quality, and (7) detailed description of outcome. Refer to Table 2 for the data extraction process.

Data analysis

We reviewed the identified studies using content analysis approach—a family of procedures for the systematic, replicable analysis texts. Content analysis is a process that involves the classification of parts of a text through the application of a structured, systematic coding scheme from which conclusions can be drawn from the message content [37]. Our study entailed quantifying the number of studies describing behavioral and cognitive interventions that included OPLHIV. Therefore, we coded for intervention type and focus, charateristics of the sample with a focus on the age category of the study participants, study design, measures used, quality of the study, and the outcomes of the interventions (significance).

After the coding process, we searched through the selected articles to identify the consideration of age in the selected studies, specifically the inclusion or specification of those older than 50. For those articles that did not explicitly identify the PLHIV over the age of 50 in their sample, we contacted the authors inquiring if they had an age breakdown of their sample. The codes related to outcomes and their relationship to age were also reviewed to assess whether any of the interventions included in the review have lessons for future interventions to address ART adherence and access to HIV care among older people in sub-Saharan Africa.

Results

We identified eight articles published from 2012 to 2017 that assessed the effectiveness of behavioral and/or cognitive interventions to improve adherence to ART medication and retention in ART care that include persons aged 50 and above in sub-Saharan Africa. All the studies identified adopted quantitative research methods. Table 3 shows a summary of study results. Five of the studies were randomized-control trials, and the other three used a pre-test/post-test with no control group research design.

The interventions evaluated in the studies included text-messaging (2) [38, 39], counseling and patient education (3) [40,41,42], home visits (1) [43], and a combination of interventions (2) [44, 45]. Five of the eight studies specified the age distribution of participants; nevertheless, only in one study [43] did those over the age of 50 make up a significant proportion of the study population. Three studies referred only to general age range (for example 18 years or older) and did not specify age categories and, therefore, it is unclear whether they actively considered those over the age of 50 [38, 39, 42]. We contacted the corresponding authors of the other three articles by email, and they provided a breakdown of the sample included in their studies.

Based on this additional information, we obtained the age distribution of all eight studies included in the review. The articles' review revealed that in most of the other studies, the size of the over 50s was about 10% or less. From the additional information obtained by emailing the corresponding authors, we had one study that had up to 21% of the participants within the age of 50+ [39] with the others conforming to the findings based on the paper reviews (10% or less of the sample). There were no studies that exclusively focused on older adults.

Only three of the selected studies had the results of the interventions broken down by age. The first, which was an assessment of the impact of a peer education intervention on viral load and adherence, found that adults over the age of 40 years were less likely to achieve viral load suppression compared to other age groups within the study [40]. The second study aimed to assess the impact of patient education on ART adherence. The authors found no significant difference in adherence before and after the intervention among those over the age of 55 years. However, for those aged between 36 and 55 years, there was a significant increase in adherence [41]. The third study assessed the impact of a combination intervention of counseling and home visits on attendance in pre-ART care. The results showed that those aged 45–70 years showed greater retention after the intervention [44].

A range of outcome measures was used to assess access to care and adherence to ART. Of all the studies included, only two studies assessing adherence to ART used a biological marker. In addition, the study by Bigogo et al. [43] assessed retention in access to care through the incidence of illness. Of the three studies reviewed above that specified differences by age, only Coker et al. [40] included a biometric measure: viral load. This study also collected self-reported adherence and cumulative pharmacy refill rates to understand adherence to ART (Coker et al. [40]). Kunutsor et al. [41] assessed adherence using self-reported adherence through pill counts at the clinic, and Lubega et al. [44] used attendance of pre-ART care visits over a period of 24 months to show retention in care; neither of these studies included biological markers.

Discussion

Even with the recognition that HIV among older persons in sub-Saharan is an on-going and a potentially growing problem as the numbers of individuals on ART and aging with HIV increases, our review and previous studies show that there is a dearth of evidence on interventions targeting older adults [7]. It is notable that in our review, not a single paper outlined an intervention specifically targeting OPLHIV to address their access to care or treatment adherence. In addition to failing to specify age or adequately consider older people, some of the studies did not include a control group, while others failed to specify any comparison by age limiting the number of studies that could actually be analyzed for potential outcomes vis-à-vis the age of the study participants. The results show that even those intervention studies that include older adults lack sufficient data to draw useful conclusions about the impact of the intervention on older adults.

The studies included in this review considered a range of outcomes. However, only two included bio-markers limiting the studies to the reliance on self-reported and subjectively measured outcomes, which could introduce potential flaws. In addition, the broad range of behavioral and cognitive outcomes assessed within the selected articles limits the true comparability of the interventions. It also limits the clear evidence of the ability of interventions to change behavior.

The Coker et al. [40] study suggests that the peer education intervention was not successful for those over the age of 50, but the poorly defined age range and composition in the oldest group (40 years plus) makes it hard to draw any clear and significant conclusions. While Kunutsor et al. [41] provide sufficiently specific results to draw conclusions about the intervention’s potential to meet OPLHIV’s needs, the results show that there was no significant change as a result of the intervention. Therefore, only in the Lubega et al. [44] study is there a suggestion that the intervention may have been successful in retaining those between 45 and 70 years in pre-ART care. Nevertheless, the generalizability of this study is limited and with the current move to Universal Test and Treat and to supporting ART adherence, there is less relevance of a study of pre-ART care. In addition, the age range is relatively large and the composition is not clear, therefore, the results cannot clearly show an impact on persons over the age of 50 specifically.

Limitations

The use of only three databases for the search of the relevant literature poses the potential risk of missing studies that could have met the inclusion criteria. The risk of missing relevant studies was reduced by conducting a manual search of the relevant studies from the reference list of the papers that were identified from the databases. This study also assumed that the previous review on which it is built was thoroughly conducted as any studies that were found prior to 2012 were not included.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the need to increase the evidence-base of interventions that will assist older Africans to access ART, remain in ART care, and adhere to treatment. Ideally, future studies to assess and improve ART access and adherence in sub-Saharan Africa should (a) target older persons living with HIV explicitly, (b) include control groups and sufficient sample sizes for statistical testing, and (c) include bio-markers and validated behavioral and cognitive outcomes. With this evidence, health policies and programs are more likely to address the needs of those aging with HIV.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Anti-retroviral therapy

- HIV:

-

Human immuno-virus

- LMIC:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- OPLHIV:

-

Older people living with HIV

- PICOT:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Time

- PLHIV:

-

People living with HIV

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

References

UNAIDS 2016. Prevention Gap Report. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2016-prevention-gap-report_en.pdf. Accessed June 2017.

Zaidi J, Grapsa E, Tanser F, Newell M-L, Bärnighausen T. Dramatic increase in HIV prevalence after scale-up of antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2013;27(14):2301–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e328362e832.

Vollmer S, Harttgen K, Alfven T, Padayachy J, Ghys P, Bärnighausen T. The HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa is aging: evidence from the demographic and health surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav. 2016:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1591-7.

Mahy M, Autenrieth CS, Stanecki K, Wynd S. Increasing trends in HIV prevalence among people aged 50 years and older: evidence from estimates and survey data. AIDS; 2014;28 Suppl 4(September):S453–S459. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000479.

UNAIDS. HIV and Aging. A special supplement to the UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. 2013. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2013/20131101_JC2563_hiv-and-aging_en.pdf. Accessed Apr 2017.

Mutevedzi PC, Newell M-L. A missing piece in the puzzle: HIV in mature adults in sub-Saharan Africa. Future Virol. 2011;6(6):755–67. https://doi.org/10.2217/fvl.11.43.

Negin J, Rozea A, Martiniuk AL. HIV behavioural interventions targeted towards older adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):507. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-507.

Mabuza E, Poggenpoel M, Myburgh C. Perceived basic needs and resources for the elderly in the peri-urban and rural communities in the Hhohho region in Swaziland. Curationis. 2010;33(1):2–3. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v33i1.1007.

Waweru LM, Kabiru EW, Mbithi JN, Some ES. Health status and health seeking behaviour of the elderly persons in Dagoretti division. Nairobi East Afr Med J. 2004;80(2):63–7.

Aboderin IAG, Beard JR. Older people’s health in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):e9–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61602-0.

Lekalakala-Mokgele E. Understanding of the risk of HIV infection among the elderly in Ga-Rankuwa, South Africa. SAHARA J. 2014;11(1):67–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17290376.2014.931816.

Hirschhorn LR, Kaaya SF, Garrity PS, Chopyak E, Fawzi MCS. Cancer and the “other” noncommunicable chronic diseases in older people living with HIV/AIDS in resource-limited settings: a challenge to success. AIDS. 2012;26:S65–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e328355ab72.

Negin J, Cumming RG. HIV infection in older adults in sub-Saharan Africa: extrapolating prevalence from existing data. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(11):847–53. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.10.076349.

Mugisha JO, Schatz EJ, Negin J, Mwaniki P, Kowal P, Seeley J. Timing of most recent health care visit by older people living with and without HIV: findings from the SAGE well-being of older people study in Uganda. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2016;0(0):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415016680071.

Nyirenda M, Newell M, Mugisha J, Mutevedzi PC, Seeley J, Scholten F, et al. Health, wellbeing, and disability among older people infected or affected by HIV in Uganda and South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):19201. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.19201.

Negin J, Nyirenda M, Seeley J, Mutevedzi P. Inequality in health status among older adults in Africa: the surprising impact of anti-retroviral treatment. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2013;28(4):491–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-013-9215-4.

Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(2):69–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-010-0041-9.

Burgess M, Zeuli JD, Kasten MJ. Management of HIV/AIDS in older patients–drug/drug interactions and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2015;7:251–64. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S39655.

Ghidei L, Simone MJ, Salow MJ, Zimmerman KM, Paquin AM, Skarf LM, Kostas TRM, Rudolph JL. Aging, Antiretrovirals, and Adherence: A Meta Analysis of Adherence among Older HIV-Infected Individuals. Drugs & Aging 2013;30(10):809–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0107-7.

Nachega JB, Hsu AJ, Uthman OA, Spinewine A, Pham PA. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and drug–drug interactions in the aging HIV population. AIDS. 2012;26:S39–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835584ea.

Chang LW, Njie-Carr V, Kalenge S, Kelly JF, Bollinger RC, Alamo-Talisuna S. Perceptions and acceptability of mHealth interventions for improving patient care at a community-based HIV/AIDS clinic in Uganda: a mixed methods study. AIDS Care. 2013;25(7):874–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.774315.

Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, O’Leary A, Ngwane Z, Icard LD, Heeren GA, et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial of an HIV/sexually transmitted infection risk-reduction intervention for South African men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):467–73. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301578.

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Wamala K, Okello J, Alderman S, Odokonyero R, Musisi S, et al. Developing a culturally sensitive group support intervention for depression among HIV infected and non-infected Ugandan adults: a qualitative study. J Affect Disord. 2014;163:10–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.042.

Wouters E, Masquillier C, Ponnet K, le Roux Booysen F. A peer adherence support intervention to improve the antiretroviral treatment outcomes of HIV patients in South Africa: the moderating role of family dynamics. Soc Sci Med. 2014;113:145–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.020.

Foster SD, Nakamanya S, Kyomuhangi R, Amurwon J, Namara G, Amuron B, et al. The experience of “medicine companions” to support adherence to antiretroviral therapy: quantitative and qualitative data from a trial population in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl 1):35–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120903500027.

Mathes T, Antoine S-L, Pieper D. Adherence-enhancing interventions for active antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Health. 2014;11(3):230. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH14025.

Illa L, Echenique M, Bustamante-Avellaneda V, Sanchez-Martinez M. Review of recent behavioral interventions targeting older adults living with HIV/AIDS. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(4):413–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-014-0231-y.

Chambers LA, Wilson MG, Rueda S, Gogolishvili D, Shi MQ, Rourke SB, et al. Evidence informing the intersection of HIV, aging and health: a scoping review. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):661–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0627-5.

Brennan-Ing M, Seidel L, Geddes L, Freeman R, Figueroa E, Havlik R, et al. Adapting a telephone support intervention to address depression in older adults with HIV. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2017:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15381501.2017.1318103.

Shah KN, Majeed Z, Yoruk YB, Yang H, Hilton TN, McMahon JM, et al. Enhancing physical function in HIV-infected older adults: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Health Psychol. 2016;35(6):563. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000311.

Gonzalez-Garcia M, Ferrer MJ, Borras X, Muñoz-Moreno JA, Miranda C, Puig J, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on the quality of life, emotional status, and CD4 cell count of patients aging with HIV infection. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):676–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0612-z.

UNAIDS. How AIDS changed everything: MDG6: 15 years, 15 lessons of hope from the AIDS response. Geneva; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/MDG6_15years-15lessonsfromtheAIDSresponse. Accessed June 2018.

Mugisha JO, Schatz EJ, Randell M, Kuteesa M, Kowal P, Negin J, et al. Chronic disease, risk factors and disability in adults aged 50 and above living with and without HIV : findings from the Wellbeing of Older People Study in Uganda. 2016;1(4):1–11. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.31098.

Monteiro F, Canavarro MC, Pereira M. Factors associated with quality of life in middle-aged and older patients living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2016:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1146209.

Richards E, Zalwango F, Seeley J, Scholten F, Theobald S. Neglected older women and men: exploring age and gender as structural drivers of HIV among people aged over 60 in Uganda. African J. AIDS Res. 2013;12(2):71–8. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2013.83136..

National Blood Lung and Heart Insititute. Quality assessment of controlled intervention studies. 2014;6–8 Retrived from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed June 2017.

Stemler S. An overview of content analysis. Pract Assessment Res Eval. 2001;7(17):1–6.

Siedner MJ, Santorino D, Lankowski AJ, Kanyesigye M, Bwana MB, Haberer JE, et al. A combination SMS and transportation reimbursement intervention to improve HIV care following abnormal CD4 test results in rural Uganda: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):160–71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0397-1.

Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Ongolo-Zogo P, Lester RT, Mills EJ, Smieja M, et al. The Cameroon mobile phone SMS (CAMPS) trial: a randomized trial of text messaging versus usual Care for Adherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):6–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046909.

Coker M, Etiebet MA, Chang H, Awwal G, Jumare J, Musa BM, et al. Socio-demographic and adherence factors associated with viral load suppression in HIV-infected adults initiating therapy in northern Nigeria: a randomized controlled trial of a peer support intervention. Curr HIV Res. 2015;13(4):279–85. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570162X13666150407143838.

Kunutsor S, Walley J, Muchuro S, Katabira E, Balidawa H, Namagala E, et al. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan African HIV-positive populations: an enhanced adherence package. AIDS Care. 2012;24(10):1308–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.661833.

Robbins RN, Mellins CA, Leu C-SS, Rowe J, Warne P, Abrams EJ, et al. Enhancing lay counselor capacity to improve patient outcomes with multimedia technology. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(S2):163–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0988-4.

Bigogo G, Amolloh M, Laserson KF, Audi A, Aura B, Dalal W, et al. The impact of home-based HIV counseling and testing on care-seeking and incidence of common infectious disease syndromes in rural western Kenya. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):376. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-376.

Lubega M, Tumwesigye NM, Kadobera D, Marrone G, Wabwire-Mangen F, Peterson S, et al. Effect of community support agents on retention of people living with HIV in pre-antiretroviral care: a randomized controlled trial in eastern Uganda. JAIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000723.

Maduka O, Obin-West CI. Adherence counseling and reminder text messages improve uptake of antiretroviral therapy in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16(3):302–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.113451.

Maduka O, Tobin-West CI. Adherence counseling and reminder text messages improve uptake of antiretroviral therapy in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 2013;16(3):302. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.113451.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Prof. Joel Negin who provided comments on an earlier draft of this paper and the assistance of authors who communicated with us about the demographic makeup of their studies reviewed in this paper. We would also like to thank the two reviewers who provided further comments to improve the quality of the article.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Missouri South African Exchange Program which is administered in collaboration with the University of the Western Cape South Africa. The funder was not involved in any of the research processes.

Availability of data and materials

Because the study was a systematic review of published studies, the full references of these studies have been provided in the reference list.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LK and ES designed the study and selected the search terms. FCM assisted with the manual selection of publications and extracted the data from the papers with support from LK. FCM also analyzed the data. LK and FCM drafted the manuscript with editorial and content input from ES. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Knight, L., Mukumbang, F.C. & Schatz, E. Behavioral and cognitive interventions to improve treatment adherence and access to HIV care among older adults in sub-Saharan Africa: an updated systematic review. Syst Rev 7, 114 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0759-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0759-9