Abstract

Background

Many interventions have been implemented to improve maternal health outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Currently, however, systematic information on the effectiveness of these interventions remains scarce. We conducted a systematic review of published evidence on non-drug interventions that reported effectiveness in improving outcomes and quality of care in maternal health in SSA.

Methods

African Journals Online, Bioline, MEDLINE, Ovid, Science Direct, and Scopus databases were searched for studies published in English between 2000 and 2015 and reporting on the effectiveness of interventions to improve quality and outcomes of maternal health care in SSA. Articles focusing on interventions that involved drug treatments, medications, or therapies were excluded. We present a narrative synthesis of the reported impact of these interventions on maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes as well as on other dimensions of the quality of maternal health care (as defined by the Institute of Medicine 2001 to comprise safety, effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, patient centeredness, and equitability).

Results

Seventy-three studies were included in this review. Non-drug interventions that directly or indirectly improved quality of maternal health and morbidity and mortality outcomes in SSA assumed a variety of forms including mobile and electronic health, financial incentives on the demand and supply side, facility-based clinical audits and maternal death reviews, health systems strengthening interventions, community mobilization and/or peer-based programs, home-based visits, counseling and health educational and promotional programs conducted by health care providers, transportation and/or communication and referrals for emergency obstetric care, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and task shifting interventions. There was a preponderance of single facility and community-based studies whose effectiveness was difficult to assess.

Conclusions

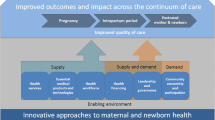

Many non-drug interventions have been implemented to improve maternal health care in SSA. These interventions have largely been health facility and/or community based. While the evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to improve maternal health is varied, study findings underscore the importance of implementing comprehensive interventions that strengthen different components of the health care systems, both in the community and at the health facilities, coupled with a supportive policy environment.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42015023750

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) continues to experience very high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality [1–3]. The region has a lifetime risk of maternal deaths of 1 in 38 [3], with an estimated 530,000 maternal deaths occurring each year [4]. These deaths account for more than 90 % of all global maternal deaths [5]. The limited availability of basic and essential maternal health services, coupled with poor implementation of maternal health care policies and programs, continues to fuel the high maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in SSA [6].

The maternal health crisis facing the region has led to a proliferation of interventions to improve the quality of maternal health services and health outcomes [7–11]. These interventions take a variety of forms, including general health system strengthening through activities like training of health care providers on key skills such as emergency obstetric care (EmOC), prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, task shifting among health care workers, demand- and supply-side financial incentives, and mobile and electronic health interventions, among others. While evidence on the effectiveness of health interventions can support improvements in service delivery and promote population wellbeing [7, 10, 12, 13], there is a lack of critical and systematic analyses of the effectiveness of existing interventions that have been implemented in SSA to improve outcomes and quality of maternal health care.

In this review, we report on non-drug interventions and their effectiveness to improve outcomes and impact the quality of maternal health care in the region. Findings from this review will provide a basis for the design, delivery, and scale-up of programs aimed at improving the quality of care offered to women in region and consequently their health outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search of papers on interventions aimed at improving the quality and effectiveness of maternal health care in SSA. The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42015023750). We undertook a computer-aided search of online journal databases comprising African Journals Online (AJOL), Bioline, MEDLINE, Ovid, Science Direct, and Scopus. In the search, the following keywords and Boolean combinations were used: “maternity,” “maternal,” “maternal mortality,” “maternal deaths,” “morbidity,” and “antenatal” in combination with “Africa” or “sub-Saharan Africa” AND “quality” AND “effectiveness.” We further supplemented the searches with rigorous manual reviews of the reference lists of all included scientific publications for relevant additional literature. In this review, we defined a “research article” as an original piece of scientific work published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. A “review article” was defined as a summary analysis of existing knowledge and insights into specific research areas published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. To be included in the current review, articles had to be peer-reviewed papers published in English between 2000 and 2015. They also needed to report outcomes of non-drug interventions that sought to improve outcomes and quality of care in maternal health in SSA. Building on Glynn et al. [14], we defined non-drug interventions as those not related to or involving the use of drugs or medication, and directed to the individual (patient), members of her family, the health care providers, or the health care system with the aim of enhancing quality of care and improving maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes. Articles were excluded if they had no clearly stated design or evaluation methods. Two reviewers (FMW and CEM) independently identified articles for inclusion in the review. Disagreements on articles selected for inclusion were resolved through discussion and consensus among FMW, CEM, ASM and COI. Where consensus was still not possible, ASM had the casting decision.

Criteria for study inclusion

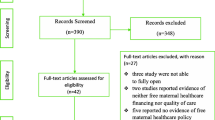

Two hundred and fifteen articles on hospital- and community-based interventions aimed at improving outcomes and quality of care in maternal health in SSA were screened. One hundred and three of these articles were based on non-drug related interventions while 112 addressed drug or pharmacological-related interventions, including anti-retroviral therapy (ART) initiation in HIV pregnant women for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, use of misoprostol for labor induction during delivery, intermittent prophylaxis therapy—presumptive treatment of uncomplicated malaria during pregnancy (using drugs such as sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and chloroquine), use of magnesium sulphate for management of eclampsia/preeclampsia, and provision of insecticide-treated nets to prevent malaria infection during pregnancy. Thirty out of the 103 articles on non-drug interventions were excluded for not reporting specific maternal outcomes, reporting process evaluation outcomes, or addressing cost effectiveness of such interventions. Fifteen of the excluded articles assessed nutritional supplementation among pregnant women, e.g., micronutrient supplementation and iron-fortified foods during pregnancy to prevent anemia and enhance safe delivery. In summary, a total of 142 studies were excluded from the current review.

Seventy-three non-drug intervention studies were included in this review. These included 24 randomized controlled trials; 16 retrospective exploratory, cohort, or comparative studies; 12 prospective exploratory, cohort, or comparative studies; 10 quasi-experimental studies, 5 studies that analyzed cross-sectional data from cluster randomized trials; one time series observational study with a control arm; one case cohort study; three cross-sectional analyses of pre- and post-intervention or case control studies; and one non-randomized pre-post study.

The PRISMA flow diagram, 2009 [15], showing the process of selecting studies for inclusion is in this review is included (Fig. 1) together with a PRISMA checklist [15] for items considered while conducting this review (Additional file 1).

The review employed the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale for case/cohort/cross-sectional studies [16] and the 5-point Jadad scale for experimental studies/RCTs [17] for quality assessment. The information on the level of the quality of evidence from the included studies is shown in the Table 1, ranging from level I to V (low to high quality). The quality checks focused on (a) representativeness of the population and population characteristics, (b) information about the study design, (c) ascertainment of exposure and intervention, and (d) use of standard definitions for main outcome measures and denominators used (e.g., for deaths). From each paper, we extracted information on issues that potentially affected the observed outcomes (i.e., frequency and duration of data collection), proportion of refusals and loss to follow-up, and sample sizes. In addition, we extracted general study information (e.g., year the study was published and authors) and the primary health outcomes for the intervention. From the findings of studies included in the review, we checked for conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the intervention in improving one or more aspects of the quality of maternal health care as defined by the Institute of Medicine 2001 (“Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century”) as having the following key dimensions: safety, efficiency, effectiveness, equitability, patient centeredness, and timeliness. A narrative synthesis highlights findings from the included studies. Due to large heterogeneity in study methodologies, outcomes, outputs, and processes, a quantitative/meta-analysis analysis was not possible.

Results and discussion

The range of interventions to improve quality of maternal care and maternal outcomes included in this paper is summarized in Table 1. The interventions were broadly classified into mobile and electronic health interventions (n = 5; 7 %); financial incentives in the form of user fee exemptions and payments to health facilities based on performance (n = 13; 18 %); clinical audits (n = 13; 18 %); health systems and infrastructure development (n = 23; 32 %); community mobilization and peer-based programs (n = 8; 11 %); home visits and counseling and educational and health promotion programs (n = 5; 7 %); emergency transportation, communication, and referrals (n = 4; 6 %); PMTCT (n = 4; 6 %); and task shifting interventions (n = 2; 3 %). Some of the studies covered in the review were included in more than one category. The summary of results of the review is presented in Table 1. Below, we highlight the key findings of the studies within each of the broad classifications.

-

1.

Mobile and electronic health interventions

Mobile health (mHealth) refers to the application of wireless, portable information and communication technologies to support health and health care [18, 19]. These interventions often involve the use of devices such as phones, computers, personal digital assistants, and digital point-of-care testing devices [20]. Although evidence of the potential value of mHealth for maternal health is just emerging, donors and development agencies continue to give considerable attention to it as a means of improving maternal health [21, 22].

Three studies on mHealth were included in this review. These studies were conducted in Nigeria [23], Rwanda [24], and Zanzibar [21]. The mHealth interventions sought to provide two- or three-way communication between women and the health care system, through provision of mobile phone messages reminding pregnant women to attend clinic days. Overall, evaluations of the mHealth interventions show that they improved utilization of, and access to maternal health services, as well as women’s attendance at primary health care facilities and services such as antenatal care (ANC). In Zanzibar, the provision of mobile phones, together with redeemable vouchers for pregnant women, reportedly improved the timing of ANC services as well as the number of women seeking and receiving preventive health services, attending ANC late in pregnancy (i.e., more ANC visits and those treated for antepartum complications). In Rwanda, the short message service (SMS)-based alert program called the Rapid SMS-MCH was used to monitor pregnancy by allowing a three-way interactive communication among a community health worker (CHW) following pregnant women in the community, a health care worker at a health facility, and an ambulance driver who would be called in to facilitate emergency transport for obstetric care. The project led to an increase in facility-based deliveries from 72 to 92 % at the end of a 12-month pilot phase.

An electronic clinical health decision system (eCDSS) implemented in Ghana [25] and the Basic Antenatal Care Information System (Bacis) implemented in South Africa [26] were shown to improve health workers’ compliance with established maternity care protocols. In Ghana, health workers’ compliance with maternal care protocols reportedly increased the detection of pregnancy complications during ANC in the health centers, consequently decreasing the number of labor-related complications. The Bacis system in South Africa improved health workers’ responsiveness and quality of services offered to their patients. It also improved the promptness and quality of services offered to mothers younger than 18 years and their retention in ANC beyond week 20. On final assessment, the Bacis program showed minimal health data input error (13.2 %) compared to the District Health Information System (DHIS) that was in use (25 %).

Mobile health and electronic health interventions may improve health care processes through lower failed appointments for services like ANC and quicker diagnosis and treatment of obstetric complications. Unreliable electricity infrastructure and supply and mobile network failure were the major challenges to the mHealth and e-health initiatives identified in this review. The interventions considered were also small in scale and at high risk of dilution of possible impact between intervention and control communities.

-

2.

Financial incentives

Financial incentives to improve access and utilization of maternal health care and service delivery have also been implemented in a number of countries in SSA [27–29]. Interventions involving financial incentives take the form of supply-side and demand-side incentives and seek to enhance equitable access to health care while improving the market supply and quality of services available to underserved populations [30, 31]. Supply-side incentives include pay for performance (P4P), performance-based financing (PBF), and various community-based insurance schemes (CBHI) and while demand-side incentives include vouchers that can be redeemed for health services, user fee exemptions, conditional cash transfers, and subsidies or cost-sharing arrangements.

We reviewed 12 studies that reported on the effectiveness of demand-side financial incentives including user fee exemptions (majorly for caesarean section deliveries), cost-sharing programs between the public and the health care facilities, and output-based approach (OBA) vouchers covering costs for ANC visits, and facility-based deliveries. Other demand-side financial incentives implemented were vouchers redeemable for emergency transport to facilitate timely movement of mothers requiring emergency obstetric care and vouchers to health service providers to redeem costs incurred for providing delivery services in their facilities. The OBA vouchers supported targeted subsidies to underserved populations in the urban slums of Nairobi increased facility-based deliveries [32, 33]. Results showed that beneficiaries of the OBA voucher were more likely to deliver a subsequent child in a health facility compared to non-beneficiaries. Fee exemption for caesarean sections increased caesarean birth rates in cities in Mali, which reportedly reduced the risk of maternal deaths from obstructed labor [34]. The Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) provided vouchers to facilitate access to health facility deliveries for women in rural Kenya. This program significantly decreased the number of home births by about 10 % and added to the number of facility-based deliveries by a similar margin [35–37]. In Ghana, exemptions from community-based health insurance program premiums increased the registration of female community members, enhancing uptake of health services and leading to improved ANC attendance, and facility-based deliveries [38]. The premium exemptions also increased access to a spectrum of other services offered at health facilities, including clinical and diagnostic services during ANC visits, counseling on safe motherhood, education on recognition of pregnancy-related danger signs, and vaccination against tetanus. A voucher system that catered for costs for ANC services and hospital delivery in Uganda raised demand for facility-based deliveries by 52.3 %, of which about 9 % were new health facility users [39]. In Nigeria, a co-financing program for maternal health between the government and the community resulted in a 60 percentage point increase in the utilization of maternal health services (from 26.7 to 85.6 %) [40], while a user fee exemption program in the same country resulted in increased uptake of institutional deliveries by up to 88 %, resulting in a decline in institutional MMR from 532 to 371 per 100,000 live births [41].

Burundi [41, 42], Ghana, Mali and Senegal [38, 43], Rwanda [44], and Uganda [39] have implemented community-based health insurance schemes, in some cases, combined with the exemption of pregnant women from the premiums payable to these schemes. The P4P scheme in Rwanda resulted in a 23 % increase in the number of institutional deliveries while in Burundi, the PBF initiative led to significant improvements in the quality of ANC services received by women at health facilities that participated in the intervention.

Financial incentives have the potential to increase access to and utilization of maternal health services especially among the poor, thereby facilitating facility-based deliveries, use of skilled care, and reduction of maternal mortality [45]. However, evidence on the impact of financial incentives on the quality of and equitable access to maternal health care in SSA is inconclusive. Some of the studies reviewed relied on small sample sizes or did not have comparison group and therefore did not offer high-quality evidence.

-

3.

Clinical audits

Several studies examined the use of audit tools including criterion-based clinical audits (CBCA) and maternal death reviews (MDR) to improve the quality of maternal care in health facilities. CBCA is a tool for measuring and improving the quality of obstetric care at health facilities with a focus on five life-threatening obstetric complications: hemorrhage, eclampsia, genital tract infection, obstructed labor, and uterine rupture [46, 47]. MDR, on the other hand, employs a qualitative approach to investigate the causes of and circumstances surrounding maternal deaths at health facilities [48]. Both approaches are combined with feedback and target setting sessions with health care providers, to improve the management of obstetric cases, improve quality of care, and reduce maternal mortality. The main element of CBCA is that performance is audited to ascertain whether guidelines were followed. The tool facilitates improvements on areas of weakness in situations where the right processes in the management of obstetric complications are not followed.

CBCA implemented in a health facility in Nigeria [49] resulted in an improvement of the overall care for obstetric complications by 20 % (from 61 to 81 %) for obstetric hemorrhage; 54 to 90 % for eclampsia; 82 to 94 % for obstructed labor and from 66 to 85 % for genital tract sepsis. Zongo et al. [50] reported that women treated at facilities where CBCA was implemented in Mali and Senegal had better clinical examination and postpartum monitoring practices. Similarly, in a study in Malawi [51, 52], the use of CBCA decreased the incidence of uterine rupture by 68 % (from 19.2 to 6.1/1000 deliveries), improved the diagnosis of maternal morbidity, and increased the number of women receiving blood transfusions and caesarean deliveries. Other studies reported that CBCA decreased the aggregate obstetric case fatality rate (CFR) by 33 % in Senegal [53] and contributed to an increase in first ANC visits, facility deliveries (from 31.8 to 34.7 %), and the quality of women-friendly services and satisfaction of women (by 9 % in Uganda) [54]. In addition, CBCA was shown to reduce institutional MMR from 250 to 182 per 100,000 live births, decrease the CFR from 3.7 to 1.5 % [55–57], improve documentation by health care workers of case notes and maternity registers, and increase caesarean delivery rate from 1.9 to 3.3 % in Burkina Faso [58].

The multifaceted QUARITE (quality of care, risk management, and technology in obstetrics) study conducted in Mali and Senegal [50] and another study on facility-based maternal death reviews conducted in Senegal [59] reported that MDR and on-site training of health care providers on EmOC reduced maternal mortality among high-risk women who delivered through caesarean section. In addition, MDR reportedly decreased obstetric complications and the overall hospital-based MMR by a massive 410 in 100,000 and led to a drop in the proportion of women who had not received any ANC services from around 11 to 4 % at the end of the intervention [59].

Although CBCA and MDR have been shown to be effective in improving the quality of EmOC and the management of obstetric cases, leading to a reduction in obstetric case fatality rates, their strength of evidence is limited. The techniques are often health facility-based interventions and do not provide a comprehensive overview of all cases of maternal deaths in a community. In addition, variability in standard checklists used in clinical audits potentially limits the replicability and comparability of clinical audits.

-

4.

Comprehensive interventions targeting health systems strengthening—training of health care workers, infrastructural upgrading, and provision of equipment and medical supplies

Strengthening health systems was considered a key pillar to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and will still be key in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [60]. Inequitable access to quality sexual and reproductive health care in SSA is exacerbated by acute shortage and unequal distribution of skilled and specialized health personnel such as physicians, midwives, and nurses [61, 62]. Efforts to address shortages in specialized care, and inequities in the distribution of skilled health personnel, have sought to build the capacity of available maternal health services providers in the provision of basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care and in conducting vital quality assurance exercises, such as maternal death reviews [63, 64].

The CARE/AMDD (Averting Maternal Death and Disability) program collaboration is a comprehensive intervention implemented in three high maternal mortality countries in Africa (Rwanda, Tanzania, and Ethiopia) aimed at increasing the availability and quality of EmOC services [65, 66]. The program supported the three countries mainly by training health care workers to provide EmOC services, strengthening existing health information systems (HIS) to monitor change, and identifying gaps in quality of care. Technical leaders and policy makers in these countries were involved in the development and formative stages of internal quality review systems, to establish nationally acceptable standards and guidelines for maternal health care. Following implementation, there was a reported increase in the availability and utilization of EmOC in Tanzania, where the met need for EmoC—defined as a percent of all women with major direct obstetric complications who are treated in a health facility providing emergency obstetric care in a given reference period—was shown to have increased slightly from 14 to 19 % over 4 years, while in Rwanda it reportedly increased met need for EmOC from 16 to 25 %. Obstetric case fatality rates were also shown to have declined by between 30 and 50 % in all the three countries. There was a reported general increase in the level of preparedness for emergencies and the ability of health care workers in these countries to manage common obstetric complications according to evidence-based practices.

Training of health care workers on emergency obstetric care was shown to have impacted positively on the availability and quality of EmOC and improved delivery and care skills among midwives in Somalia [67]. It was also associated with improved knowledge and confidence in carrying out clinical audits among health care professionals. The program reportedly reduced hospital-based mortality in first-level referral hospitals in the country [68]. In Kenya, training of health care workers on EmOC was associated with decreased rates of postpartum hemorrhage [69]. Similarly, health providers trained on providing care for postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) under the Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) program in Tanzania led to a reduction in the incidence of PPH from 32.9 to 18.2 % and that of severe PPH from 9.2 to 4.3 % [70].

The Integrated Maternal Newborn and Child Health Program in Nigeria (an intervention that was based on a network of CHWs, who connect between households and the health facilities) [71]; the FIGO Save the Mothers Initiative in Ethiopia that aimed to establish basic and comprehensive EmOC in order to increase the availability and utilization of quality obstetric care based on UN indicators; and the Maternal Health in Ethiopia Partnership (MaNHEP) in Ethiopia that was based on community-oriented model for improving maternal and newborn health [72–74] were all reported to have improved access and the delivery of quality caesarean section to women and decreased obstetric case fatality rates. A skilled care initiative was also shown to have led to a 34 % decline in pregnancy-related mortality and the reduction in adverse pregnancy outcomes (obstetric complications and deaths) in Ethiopia and in Burkina Faso, respectively [75, 76].

The quality improvement packages, incorporating, among other things, quality assurance and provision of equipment were shown to have improved performance of health care providers in counseling women on recognizing and managing maternal complications in Kenya [77]. In Nigeria, an obstetric service quality assurance [78], together with improvements in infrastructure, provision of equipment, and continuous maternal and fetal data collection, analysis, and feedback, was shown to have lowered mean institutional MMR from 1790 per 100,000 births in 2008 to 940 per 100,000 births in 2009.

In Burkina Faso, health care providers were trained on routines and the provision of EmOC services, available referral systems were strengthened, health infrastructure was upgraded, and equipment as well as medical supplies including essential drugs were provided. This strengthening of community and health facility systems increased facility-based deliveries from 24 to 56 % and attendance by skilled care providers from 33 to 65 % among the women who reported an obstetric complication. The authors reported an increase in first ANC visits by women and their partners [58, 79]. A study on a participatory quality improvement intervention conducted in 21 health facilities in South Africa enhanced the uptake of CD4 testing from 40 to 97 %. In addition, it showed an improved uptake of maternal and infant nevirapine from 57 to 96 % and 15 to 68 % respectively, as well as an increase in the 6-week polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing from 24 to 68 % [80], adding to efforts to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Improvements in infrastructure, human resource development, transportation and communication systems, and management of health facilities were associated with the growth of fully functional EmOC facilities from 4 to 18 in Mozambique, a steady increase in number of complications treated, and a 50 % decline in deaths from obstetric complications. The met need for EmOC also reportedly increased 3-fold (from 11.3 to 32.8 %) in all facilities while births from caesarean section deliveries increased steadily, doubling at the end of the intervention. There was also a reduction of aggregate obstetric CFR by almost half (2.9 to 1.6 %); with concomitant decline in the deaths from obstetric hemorrhage, obstructed labor, and postpartum sepsis [81]. A community-based basic ultrasound service significantly reduced referrals to a regional center for fetal surveillance and delivery in South Africa [82]. In Uganda, health facility capacity strengthening was shown to have significantly improved the number of pregnant women delivering in the health facility from 55.2 to 99.3 % following the provision of mama-kits (delivery kits) [54]. A quality improvement package incorporating quality assurance for health facilities was linked to enhanced counseling and technical aspects of service provision in family planning and antenatal care in Uganda [83], and in Ghana [84], a 34 % decrease in maternal mortality, a decrease from 3.1 to 1.1 % of case fatality rates for preeclampsia and hemorrhage, and a reduction in stillbirths by 36 %. An overall decrease in maternal mortality ratio from 496 per 100,000 live births in 2007 to 328 per 100 000 in 2009 was also reported.

-

5.

Community mobilization, peer-based interventions, or support programs

Community mobilization (CM) interventions seek to empower communities to modify power dynamics and form sustainable environments for better health [85]. CM may improve equitable access to health care services through individual capacity building skills, advocacy, and community actions [86–88]. Similarly, peer-based interventions or peer support are becoming popular as a strategy to improve access to and utilization of maternal health care especially for pregnant women living with HIV (WLH) [89, 90].

In rural Malawi, coupling facility quality improvements and community activities involving the sensitization and mobilization of the women using participatory approaches was shown to enhance the quality of maternal care provided [91]. A community-based safe motherhood intervention by skilled birth attendants also reportedly promoted the utilization of obstetric care in rural Tanzania [92], while family meetings in addition to labor and birth notification in Ethiopia were associated with an increase in the uptake of institutional-based deliveries [73]. In Kenya, the community health strategy implemented by the government used community health workers to deliver maternal and newborn care through household visits to screen pregnant mothers for danger signs and to provide support for birth planning and referrals. The initiative was reported as having significantly increased ANC attendance among pregnant women from 39 to 62 % as well as deliveries by skilled birth attendants from 31 to 57 %. The program was also associated with increased HIV testing during pregnancy from 73 to 90 % [93].

Community mobilization efforts to sensitize women to deliver in health facilities and encourage participation of men in the ANC attendance and HIV testing were conducted in rural Tanzania [92, 94]. Women were taught to make birth plans including places of delivery, savings to offset costs, and preparations for complications during pregnancy, labor, delivery, and the postnatal period. Findings indicate that the intervention improved both the utilization of health units for delivery and postnatal care within one month of delivery, without any significant negative effect on providers’ and women’s satisfaction with the ANC they provided or received respectively. Women in the intervention were shown to have discussed most elements of the birth plan with their providers, including how to recognize danger signs, identifying a delivery place, and making financial and transport arrangements for delivery. Women in the intervention arm were shown to be 16.8 % more likely to deliver in a health unit than women in the control arm and were 22.7 versus 2.2 % more likely to attend postnatal care within the first 48 h.

Other studies conducted in Burkina Faso, Uganda, and Zambia also found that community mobilization increased the level of health information about danger signs and risk factors in pregnancy and first ANC visits and health facility use and deliveries [54, 95, 96]. Community mobilization also reduced perinatal mortality rates. Similarly, peer mentor interventions by WLH on pregnant WLH at the antenatal and primary health care clinics were linked to significantly higher likelihood of completion of both maternal and infant ARV therapy regimens, increased adherence to all PMTCT tasks through 1.5 months after delivery, increased likelihood of asking partners to test for HIV, and lower likelihood of reporting depressed mood [90].

-

6.

Home visits and counseling by health care workers

Home visits by health care workers, and usually community health workers (CHWs), is another strategy used to promote access to maternal health care in SSA for underserved communities [97–99]. In South Africa, home visits by CHWs to mothers in their neighborhood [89] reportedly improved adherence to condom use among pregnant WLH [100]. Similarly, volunteer peer counselor health education by women’s groups was shown to have decreased MMR by up to 52 % in poor rural populations in Malawi [101]. Birth plan counseling and health education during ANC were associated with increased uptake of skilled delivery and post-delivery care in Tanzania without negatively affecting women’s and providers’ satisfaction with available ANC services [94]. Job aids which are pictorial or illustrated cards used in counseling by nurses and midwives in Benin were said to be positively perceived by providers and pregnant women and associated with significant improvements in birth preparedness, danger sign recognition, safe and hygienic delivery, and even newborn care [102].

-

7.

Emergency transportation, communication, and referrals

An intervention that provided free-of-charge 24-h ambulance and communication services between patients and health care providers reportedly increased access to and utilization of maternal health services, particularly caesarean delivery services from 0.57 to 1.21 % in Uganda. Also reported was a 50 % increase in the number of hospital deliveries, with a slight reduction in the average hospital stillbirths [103]. In South Africa, an inter-facility transportation scheme was associated with decreased institutional-based maternal mortality from 279 per 100,000 live births before implementation of the intervention in 2011 to 152 per 100,000 live births during implementation in 2012 [104]. CURGO (Centre d’UrgenceGyneco-Obstetric), an emergency obstetric care patient transfer system in Burundi, involving the relocation of patients requiring emergency obstetric care from public hospitals to a referral facility set up by the Médecins Sans Frontières was said to have averted 74 % of maternal deaths in Kabezi district [105]. A maternity referral system that included basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care, transportation to obstetric health services and community cost-sharing schemes in Mali [106] was associated with an increase in the number of women receiving emergency obstetric care and caesarean sections performed for absolute maternal indications from 0.13 to 0.46 %. Institutional deliveries also increased from 19 % at baseline to 39.4 % at the completion of the intervention. Overall, the intervention was said to have reduced the risk of death by half in women treated for an obstetric emergency, with nearly half [47.5 %] of the reduction in deaths attributable to fewer deaths from hemorrhage.

-

8.

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV programs often come as a set of interventions and are reported to be highly effective in the eradication of vertical transmission of HIV [107, 108]. While PMTCT coverage and utilization has remarkably increased over the past decade in SSA, it is still far from the recommended targets [108]. Community mobilization, as previously discussed, was employed in Uganda to encourage male partners’ acceptance of HIV testing through couple attendance at ANC. Findings showed a 16 % improvement in the number of women who attended ANC together with their partners, while 95 % of male partners who attended the ANC together with their spouses were tested for HIV [54, 109, 110]. Training of health care workers to offer PMTCT services and equipping health facilities with supplies in Mali and Senegal was shown to have produced significantly better quality obstetric care results [110, 111]. The number of pregnant women attending first ANC visit was said to have increased 11-fold in Northern Uganda, while the number of male partners counseled, tested, and given results for HIV together with their wives at the first ANC visit also rose significantly. In Cote d'Ivoire, a significant rise in the number of pregnant women delivering in the health facilities was reported following the intervention [112].

-

9.

Task shifting interventions

Task shifting has been shown to be effective in improving maternal health care provision for patients in LMICs, most notably in the administration of ARV therapy [113, 114], non-communicable disease management [115–117], and mental health care [118]. Task shifting interventions involve equipping a cadre of staff in the health care system with the appropriate skills to provide services that would otherwise be provided by higher cadre providers, who are often scarce. In some countries in SSA, non-physician clinicians (NPCs) have been used to fill various roles that are conventionally handled by physicians [119–121]. In Benin, antenatal counseling by lay nurse aides was shown to have resulted in improvements in maternal knowledge among women in prenatal care compared to those counseled by nursing midwives. It also reportedly improved birth preparedness and recognition of danger signs in pregnancy [122]. In Ethiopia, NPCs were said to have performed 63 % of emergency caesarean section deliveries, reducing the number of maternal and fetal deaths experienced and reducing the length of hospital stay for patients in the country [123].

Limitations of the study

It is important to highlight few limitations in our strategy. Limiting selection of the papers for inclusion to those published in English in selected databases raises the possibility that we could have excluded relevant research published in other languages or not indexed in the selected databases. Also, gray literature was not included in this review. Lastly, we are not able to assess the extent to which geographical, temporal, health systems and patient risk profiles affected maternal outcomes or confounded interpretations.

Conclusions

Most of the non-drug interventions identified in this review targeted health systems capacity strengthening, including upgrading of the infrastructure with new construction and facelifts; provision of equipment and supplies to enhance maternal health care service provision; and training of health care workers to impact specialist skills for emergency obstetric care, criterion-based clinical audits and maternal death reviews, and PMTCT. Promotion of safe motherhood—as a right—is of crucial importance [124]. Effective communication and emergency transport services and prompt referrals for emergency obstetric care may reduce maternal mortality by addressing the three delays occasioned by (1) deciding when to seek appropriate medical help for an obstetric emergency, (2) reaching an appropriate obstetric facility, and (3) receiving adequate care when a facility is reached [125]. Community mobilization was linked to increased community awareness about the importance of seeking and utilizing skilled maternal care, while financial incentives through provision of redeemable vouchers, fee exemptions and community-based health insurance schemes were shown to facilitate access to and utilization of maternal health care by underserved populations.

Interventions that targeted strengthening health systems through processes like building capacity of health workers at the facility and community levels were shown to have led to the development of human resources with appropriate skills and increased coverage for maternal health services. Consequently, they were associated with improvements in the quality of care provided and reduction in obstetric complications and maternal deaths in such communities. Task shifting interventions offer a good alternative to provision of maternal health care, since they often employ competent non-physician qualified persons who earn lower remunerations and incur lower training costs compared to physicians. However, a higher level of supervision may be required for such personnel to deliver the expected impact services.

There are several non-drug interventions implemented in SSA aimed at improving the quality of maternal health services and care. Evidence on the effectiveness of the non-drug interventions on maternal outcomes as well as quality of maternal health varies. There is a preponderance of single facility and community-based studies whose effectiveness was difficult to assess. Implementation of elaborate and comprehensive interventions that strengthen different sectors of the existing health care systems, both in the community and at the health facilities, coupled with a supportive policy environment has the potential to not only improve the quality of maternal health care in SSA but save the lives of many women. Africa, as a region, fell short of achieving the MDGs 4 and 5 but has an opportunity to achieve more with the newly launched SDGs especially if decision making is guided by robust scientific evidence. Essentially, efforts to improve the quality of care and health outcomes for women in SSA must be guided by evidence about what works.

Abbreviations

ALSO, advanced life support in obstetrics; AMDD, averting maternal death and disability; ANC, antenatal care; ARV, anti-retroviral therapy; CBCA, criterion-based clinical audits; CBHI, community-based health insurance; CFA, case fatality rate; CHW, community health worker; CM, community mobilization; DHIS, district health information system; eCDSS, electronic clinical decision support system; EmOC, emergency obstetric care; IMNCH, integrated maternal newborn and child health; LMICs, low- and middle-income countries; MaNHEP, maternal health in ethiopia partnership; MCH, maternal and child health; MDG, millennium development goals; MDR, maternal death reviews; MMR, maternal mortality rate/ratio; NPC, non-physician clinician; OBA, output-based approach; P4P, payment for performance; PBF, performance-based financing; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage; PROSPERO, prospective register of systematic reviews; QUARITE, quality of care, risk management and technology in obstetrics; RCT, randomized controlled trials; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa; SDGs, sustainable development goals; SMI, safe motherhood initiative; SMS, short messaging service; WLH, women living with HIV

References

Prual A, Bouvier-Colle M, de Bernis L, Breart G. Severe maternal morbidity from direct obstetric causes in West Africa: incidence and case fatality rates. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(5):593–602.

Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1066–74.

World Health Organization & UNICEF. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division: Executive Summary. 2014.

World Health Organization. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research; 2003. p. 379.

Annan KA. Maternal Health: Investing in the Lifeline of Healthy Societies and Economies. Geneva, Switzerland: Africa Progress Panel; 2010.

Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–104.

Althabe F, Bergel E, Cafferata ML, Gibbons L, Ciapponi A, Alemán A, et al. Strategies for improving the quality of health care in maternal and child health in low‐and middle‐income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22(s1):42–60.

Opiyo N, English M. In‐service training for health professionals to improve care of the seriously ill newborn or child in low and middle‐income countries (Review). Cochrane Library. 2010 [Epub ahead of print].

Van Lonkhuijzen L, Dijkman A, van Roosmalen J, Zeeman G, Scherpbier A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of training in emergency obstetric care in low‐resource environments. BJOG. 2010;117(7):777–87.

Raven J, Hofman J, Adegoke A, Van Den Broek N. Methodology and tools for quality improvement in maternal and newborn health care. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;114(1):4–9.

Pirkle C, Dumont A, Zunzunegui M. Criterion-based clinical audit to assess quality of obstetrical care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(4):456–63.

Haws RA, Thomas AL, Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL. Impact of packaged interventions on neonatal health: a review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22(4):193–215.

Nyamtema A, Urassa D, van Roosmalen J. Maternal health interventions in resource limited countries: a systematic review of packages, impacts and factors for change. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):30.

Glynn LG, et al. Self-monitoring and other non-pharmacological interventions to improve the management of hypertension in primary care: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice. 2010;60(581):e476–e488.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12.

Istepanian RS, Zitouni K, Harry D, Moutosammy N, Sungoor A, Tang B, et al. Evaluation of a mobile phone telemonitoring system for glycaemic control in patients with diabetes. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15(3):125–8.

Istepanian RS, Jovanov E, Zhang Y. Guest editorial introduction to the special section on m-health: Beyond seamless mobility and global wireless health-care connectivity. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2004;8(4):405–14.

Nurmatov UB, Lee SH, Nwaru BI, Mukherjee M, Grant L, Pagliari C. The effectiveness of mHealth interventions for maternal, newborn and child health in low–and middle–income countries: protocol for a systematic review and meta–analysis. J Glob Health. 2014;4(1):010407.

Lund S, Nielsen BB, Hemed M, Boas IM, Said A, Said K, et al. Mobile phones improve antenatal care attendance in Zanzibar: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):29.

Kay M, Santos J, Takane M. mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies. GSMA mHA Mobile Health Summit Cape Town 7 June 2011: World Health Organization; 2011. p. 66-71.

Oyeyemi SO, Wynn R. Giving cell phones to pregnant women and improving services may increase primary health facility utilization: a case–control study of a Nigerian project. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):8.

Ngabo F, Nguimfack J, Nwaigwe F, Mugeni C, Muhoza D, Wilson DR, et al. Designing and implementing an innovative SMS-based alert system (RapidSMS-MCH) to monitor pregnancy and reduce maternal and child deaths in Rwanda. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:31.

Dalaba MA, Akweongo P, Aborigo RA, Saronga HP, Williams J, Blank A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of clinical decision support system in improving maternal health care in Ghana. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125920.

Horner V, Rautenbach P, Mbananga N, Mashamba T, Kwinda H. An e-health decision support system for improving compliance of health workers to the maternity care protocols in South Africa. Appl Clin Inform. 2013;4(1):25–36.

Morgan L, Stanton ME, Higgs ES, Balster RL, Bellows BW, Brandes N, et al. Financial incentives and maternal health: where do we go from here? J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(4 Suppl 2):S8.

Stanton ME, Higgs ES, Koblinsky M. Investigating financial incentives for maternal health: an introduction. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(4 Suppl 2):S1.

Witter S, Toonen J, Meessen B, Kagubare J, Fritsche G, Vaughan K. Performance-based financing as a health system reform: mapping the key dimensions for monitoring and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):367.

World Health Organization. The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage: executive summary. 2010.

World Health Organization. Closing the gap: policy into practice on social determinants of health: discussion paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

Bellows B, Kyobutungi C, Mutua MK, Warren C, Ezeh A. Increase in facility-based deliveries associated with a maternal health voucher programme in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2012;28:134–42. czs030.

Amendah DD, Mutua MK, Kyobutungi C, Buliva E, Bellows B. Reproductive Health voucher program and facility based delivery in informal settlements in Nairobi: a longitudinal analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80582.

Fournier P, Dumont A, Tourigny C, Philibert A, Coulibaly A, Traore M. The free caesareans policy in low-income settings: an interrupted time series analysis in Mali (2003–2012). PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105130.

Obare F, Warren C, Abuya T, Askew I, Bellows B. Assessing the population-level impact of vouchers on access to health facility delivery for women in Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:183–9.

Obare F, Warren C, Njuki R, Abuya T, Sunday J, Askew I, et al. Community-level impact of the reproductive health vouchers programme on service utilization in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(2):165–75.

Watt C, Abuya T, Warren CE, Obare F, Kanya L, Bellows B. Can reproductive health voucher programs improve quality of postnatal care? A quasi-experimental evaluation of Kenya’s safe motherhood voucher scheme. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122828.

Frimpong JA, Helleringer S, Awoonor-Williams JK, Aguilar T, Phillips JF, Yeji F. The complex association of health insurance and maternal health services in the context of a premium exemption for pregnant women: a case study in Northern Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(8):1043–53.

Alfonso YN, Bishai D, Bua J, Mutebi A, Mayora C, Ekirapa-Kiracho E. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a voucher scheme combined with obstetrical quality improvements: quasi experimental results from Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(1):88–99.

Adinma E, Adinma JB-D, Obionu C, Asuzu M. Effect of government-community healthcare co-financing on maternal and child healthcare in Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2011;30(1):35–41.

Ezugwu E, Onah H, Iyoke C, Ezugwu F. Obstetric outcome following free maternal care at Enugu State University Teaching Hospital (ESUTH), Parklane, Enugu, South-eastern Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31(5):409–12.

Bonfrer I, Van de Poel E, Van Doorslaer E. The effects of performance incentives on the utilization and quality of maternal and child care in Burundi. Soc Sci Med. 2014;123:96–104.

Smith KV, Sulzbach S. Community-based health insurance and access to maternal health services: evidence from three West African countries. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(12):2460–73.

Basinga P, Gertler PJ, Binagwaho A, Soucat AL, Sturdy J, Vermeersch CM. Effect on maternal and child health services in Rwanda of payment to primary health-care providers for performance: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1421–8.

O’Donnell O. Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(12):2820–34.

Wagaarachchi PT, Graham WJ, Penney GC, McCaw-Binns A, Yeboah Antwi K, Hall MH. Holding up a mirror: changing obstetric practice through criterion-based clinical audit in developing countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2001;74(2):119–30.

Graham W, Wagaarachchi P, Penney G, McCaw-Binns A, Yeboah Antwi K, Hall M. Criteria for clinical audit of the quality of hospital-based obstetric care in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(5):614–20.

World Health Organization. Beyond the numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. 2004.

Hunyinbo K, Fawole A, Sotiloye O, Otolorin E. Evaluation of criteria-based clinical audit in improving quality of obstetric care in a developing country hospital. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;12(3):59–70.

Zongo A, Dumont A, Fournier P, Traore M, Kouanda S, Sondo B. Effect of maternal death reviews and training on maternal mortality among cesarean delivery: post-hoc analysis of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;185:174–80.

van den Akker T, van Rhenen J, Mwagomba B, Lommerse K, Vinkhumbo S, van Roosmalen J. Reduction of severe acute maternal morbidity and maternal mortality in Thyolo District, Malawi: the impact of obstetric audit. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20776.

van den Akker T, Mwagomba B, Irlam J, van Roosmalen J. Using audits to reduce the incidence of uterine rupture in a Malawian district hospital. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107(3):289–94.

Dumont A, Gaye A, Mahé P, Bouvier‐Colle MH. Emergency obstetric care in developing countries: impact of guidelines implementation in a community hospital in Senegal. BJOG. 2005;112(9):1264–9.

Ediau M, Wanyenze RK, Machingaidze S, Otim G, Olwedo A, Iriso R, et al. Trends in antenatal care attendance and health facility delivery following community and health facility systems strengthening interventions in Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):189.

Kongnyuy EJ, Mlava G, Van Den Broek N. Criteria‐based audit to improve women‐friendly care in maternity units in Malawi. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35(3):483–9.

Kongnyuy EJ, Mlava G, Van Den Broek N. Using criteria-based audit to improve the management of postpartum haemorrhage in resource limited countries: a case study of Malawi. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(6):873–8.

Kongnyuy E, Leigh B, Van den Broek N. Effect of audit and feedback on the availability, utilisation and quality of emergency obstetric care in three districts in Malawi. Women Birth. 2008;21(4):149–55.

Richard F, Ouedraogo C, De Brouwere V. Quality cesarean delivery in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: a comprehensive approach. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;103(3):283–90.

Dumont A, Gaye A, de Bernis L, Chaillet N, Landry A, Delage J, et al. Facility-based maternal death reviews: effects on maternal mortality in a district hospital in Senegal. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(3):218–24.

Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, Pang T, Bhutta Z, Hyder AA, et al. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2004;364(9437):900–6.

Kowalewski M, Jahn A. Health professionals for maternity services: experiences on covering the population with quality maternity care. Safe motherhood strategies: a review of the evidence. 2000.

Pittrof R, Campbell OM, Filippi VG. What is quality in maternity care? An international perspective. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(4):277–83.

Gerein N, Green A, Pearson S. The implications of shortages of health professionals for maternal health in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(27):40–50.

Kinney MV, Kerber KJ, Black RE, Cohen B, Nkrumah F, Coovadia H, et al. Sub-Saharan Africa’s mothers, newborns, and children: where and why do they die. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000294.

Kayongo M, Rubardt M, Butera J, Abdullah M, Mboninyibuka D, Madili M. Making EmOC a reality—CARE’s experiences in areas of high maternal mortality in Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;92(3):308–19.

Kayongo M, Butera J, Mboninyibuka D, Nyiransabimana B, Ntezimana A, Mukangamuje V. Improving availability of EmOC services in Rwanda—CARE’s experiences and lessons learned at Kabgayi Referral Hospital. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;92(3):291–8.

Ameh C, Adegoke A, Hofman J, Ismail FM, Ahmed FM, van den Broek N. The impact of emergency obstetric care training in Somaliland, Somalia. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;117(3):283–7.

Dumont A, Fournier P, Abrahamowicz M, Traore M, Haddad S, Fraser WD. Quality of care, risk management, and technology in obstetrics to reduce hospital-based maternal mortality in Senegal and Mali (QUARITE): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9887):146–57.

Spitzer RF, Steele SJ, Caloia D, Thorne J, Bocking AD, Christoffersen-Deb A, et al. One-year evaluation of the impact of an emergency obstetric and neonatal care training program in Western Kenya. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;127(2):189–93.

Sorensen BL, Rasch V, Massawe S, Nyakina J, Elsass P, Nielsen BB. Impact of ALSO training on the management of prolonged labor and neonatal care at Kagera Regional Hospital, Tanzania. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;111(1):8–12.

Findley SE, Uwemedimo OT, Doctor HV, Green C, Adamu F, Afenyadu GY. Early results of an integrated maternal, newborn, and child health program, Northern Nigeria, 2009 to 2011. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1034.

Mekbib T, Kassaye E, Getachew A, Tadesse T, Debebe A. The FIGO save the mothers initiative: the Ethiopia–Sweden collaboration. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;81(1):93–102.

Tesfaye S, Barry D, Gobezayehu AG, Frew AH, Stover KE, Tessema H, et al. Improving coverage of postnatal care in rural Ethiopia using a community‐based, collaborative quality improvement approach. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2014;59(s1):S55–64.

Sibley LM, Tesfaye S, Fekadu Desta B, Hailemichael Frew A, Kebede A, Mohammed H, et al. Improving maternal and newborn health care delivery in rural Amhara and Oromiya regions of Ethiopia through the Maternal and Newborn Health in Ethiopia Partnership. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2014;59(s1):S6–S20.

Worku AG, Yalew AW, Afework MF. The contributions of maternity care to reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes: a cohort study in Dabat District, Northwest Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(6):1336–44.

Hounton S, Menten J, Ouédraogo M, Dubourg D, Meda N, Ronsmans C, et al. Effects of a Skilled Care Initiative on pregnancy‐related mortality in rural Burkina Faso. Tropical Med Int Health. 2008;13(s1):53–60.

Warren C, Mwangi A, Oweya E, Kamunya R, Koskei N. Safeguarding maternal and newborn health: improving the quality of postnatal care in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(1):24–30.

Galadanci H, Künzel W, Shittu O, Zinser R, Gruhl M, Adams S. Obstetric quality assurance to reduce maternal and fetal mortality in Kano and Kaduna State hospitals in Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;114(1):23–8.

Brazier E, Andrzejewski C, Perkins ME, Themmen EM, Knight RJ, Bassane B. Improving poor women’s access to maternity care: findings from a primary care intervention in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(5):682–90.

Doherty T, Chopra M, Nsibande D, Mngoma D. Improving the coverage of the PMTCT programme through a participatory quality improvement intervention in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):406.

Santos C, Diante Jr D, Baptista A, Matediane E, Bique C, Bailey P. Improving emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: the story of Sofala. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;94(2):190–201.

Geerts L, Theron A, Grove D, Theron G, Odendaal H. A community-based obstetric ultrasound service. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;84(1):23–31.

Agha S. The impact of a quality‐improvement package on reproductive health services delivered by private providers in Uganda. Stud Fam Plan. 2010;41(3):205–15.

Srofenyoh E, Ivester T, Engmann C, Olufolabi A, Bookman L, Owen M. Advancing obstetric and neonatal care in a regional hospital in Ghana via continuous quality improvement. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;116(1):17–21.

Altman L, Kuhlmann AKS, Galavotti C. Understanding the black box: a systematic review of the measurement of the community mobilization process in evaluations of interventions targeting sexual, reproductive, and maternal health. Eval Program Plann. 2015;49:86–97.

Lehmann U, Friedman I, Sanders D. Review of the utilisation and effectiveness of community-based health workers in Africa. Global Health Trust, Joint Learning Initiative on Human Resources for Health and Development (JLI), JLI Working Paper. 2004:4-1.

Bhutta ZA, Soofi S, Cousens S, Mohammad S, Memon ZA, Ali I, et al. Improvement of perinatal and newborn care in rural Pakistan through community-based strategies: a cluster-randomised effectiveness trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9763):403–12.

Perry H, Zulliger R, Scott K, Javadi D, Gergen J, Shelley K. Case studies of large-scale community health worker programs: examples from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Nepal, Pakistan, Rwanda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Washington: MCHIP (Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program); 2014. Developing and strengthening community health worker programs at scale: a reference guide and case studies for program managers and policymakers.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, le Roux IM, Harwood JM, Comulada S, O’Connor MJ, et al. A cluster randomised controlled effectiveness trial evaluating perinatal home visiting among South African mothers/infants. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e105934.

Richter L, Rotheram-Borus M, Van Heerden A, Stein A, Tomlinson M, Harwood J, et al. Pregnant Women Living with HIV (WLH) supported at clinics by peer WLH: a cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):706–15.

Colbourn T, Nambiar B, Bondo A, Makwenda C, Tsetekani E, Makonda-Ridley A, et al. Effects of quality improvement in health facilities and community mobilization through women’s groups on maternal, neonatal and perinatal mortality in three districts of Malawi: MaiKhanda, a cluster randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Int Health. 2013;5:180–95. iht011.

Mushi D, Mpembeni R, Jahn A. Effectiveness of community based safe motherhood promoters in improving the utilization of obstetric care. The case of Mtwara Rural District in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1):14.

Wangalwa G, Cudjoe B, Wamalwa D, Machira Y, Ofware P, Ndirangu M, et al. Effectiveness of Kenya’s Community Health Strategy in delivering community-based maternal and newborn health care in Busia County, Kenya: non-randomized pre-test post test study. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13 Suppl 1:12.

Magoma M, Requejo J, Campbell O, Cousens S, Merialdi M, Filippi V. The effectiveness of birth plans in increasing use of skilled care at delivery and postnatal care in rural Tanzania: a cluster randomised trial. Tropical Med Int Health. 2013;18(4):435–43.

Ensor T, Green C, Quigley P, Badru AR, Kaluba D, Kureya T. Mobilizing communities to improve maternal health: results of an intervention in rural Zambia. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(1):51–9.

Hounton SH, Byass P, Brahima B. Towards reduction of maternal and perinatal mortality in rural Burkina Faso: communities are not empty vessels. Global Health Action. 2009;2.

Olds DL, Kitzman H, Cole R, Robinson J, Sidora K, Luckey DW, et al. Effects of nurse home-visiting on maternal life course and child development: age 6 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1550–9.

Gogia S, Sachdev HS. Home visits by community health workers to prevent neonatal deaths in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(9):658–66.

Olds DL, Robinson J, Pettitt L, Luckey DW, Holmberg J, Ng RK, et al. Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1560–8.

le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM, O’CONNOR MJ, Worthman CM, Mbewu N, et al. Outcomes of home visits for pregnant mothers and their infants: a cluster randomised controlled trial. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1461.

Lewycka S, Mwansambo C, Rosato M, Kazembe P, Phiri T, Mganga A, et al. Effect of women’s groups and volunteer peer counselling on rates of mortality, morbidity, and health behaviours in mothers and children in rural Malawi (MaiMwana): a factorial, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1721–35.

Jennings L, Yebadokpo AS, Affo J, Agbogbe M. Antenatal counseling in maternal and newborn care: use of job aids to improve health worker performance and maternal understanding in Benin. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1):75.

Mucunguzi S, Wamani H, Lochoro P, Tylleskar T. Effects of improved access to transportation on emergency obstetric care outcomes in Uganda. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18(3):87–94.

Schoon MG. Impact of inter-facility transport on maternal mortality in the Free State Province. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(8):534–6.

Tayler‐Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, Boogaard W, Nyandwi G, Reid T, et al. Achieving the Millennium Development Goal of reducing maternal mortality in rural Africa: an experience from Burundi. Tropical Med Int Health. 2013;18(2):166–74.

Fournier P, Dumont A, Tourigny C, Dunkley G, Dramé S. Improved access to comprehensive emergency obstetric care and its effect on institutional maternal mortality in rural Mali. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(1):30–8.

Adane D. Effectiveness of PMTCT programs in Sub-Saharan Africa, a meta-analysis. Umea: Umea University; 2012.

Hampanda K. Vertical transmission of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: applying theoretical frameworks to understand social barriers to PMTCT. Infect Dis. 2012;2013:5.

Byamugisha R, Åstrøm AN, Ndeezi G, Karamagi CA, Tylleskär T, Tumwine JK. Male partner antenatal attendance and HIV testing in eastern Uganda: a randomized facility-based intervention trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14(1):43.

Pirkle CM, Dumont A, Traoré M, Zunzunegui M-V. Training and nutritional components of PMTCT programmes associated with improved intrapartum quality of care in Mali and Senegal. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(2):174–83.

Pirkle C, Dumont A, Traore M, Zunzunegui M-V, et al. Effect of a facility-based multifaceted intervention on the quality of obstetrical care: a cluster randomized controlled trial in Mali and Senegal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):24.

Delvaux T, Diby Konan J-P, Aké-Tano O, Gohou-Kouassi V, Bosso PE, Buvé A, et al. Quality of antenatal and delivery care before and after the implementation of a prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in Côte d’Ivoire. Tropical Med Int Health. 2008;13(8):970–9.

Lazarus JV, Safreed-Harmon K, Nicholson J, Jaffar S. Health service delivery models for the provision of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Tropical Med Int Health. 2014;19(10):1198–215.

O’Malley G, Asrat L, Sharma A, Hamunime N, Stephanus Y, Brandt L, et al. Nurse task shifting for antiretroviral treatment services in Namibia: implementation research to move evidence into action. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92014.

Joshi R, Alim M, Kengne AP, Jan S, Maulik PK, Peiris D, et al. Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries—a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103754.

Ogedegbe G, Plange-Rhule J, Gyamfi J, Chaplin W, Ntim M, Apusiga K, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of task shifting and blood pressure control in Ghana: study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:73.

Mdege ND, Chindove S, Ali S. The effectiveness and cost implications of task-shifting in the delivery of antiretroviral therapy to HIV-infected patients: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(3):223–36.

Petersen I, Lund C, Bhana A, Flisher AJ. A task shifting approach to primary mental health care for adults in South Africa: human resource requirements and costs for rural settings. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(1):42–51.

Samb B, Celletti F, Holloway J, Van Damme W, De Cock KM, Dybul M. Rapid Expansion of the Health Workforce in Response to the HIV Epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(24):2510–4.

Mullan F, Frehywot S. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 2008;370(9605):2158–63.

McPake B, Mensah K. Task shifting in health care in resource-poor countries. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):870–1.

Jennings L, Yebadokpo AS, Affo J, Agbogbe M, Tankoano A. Task shifting in maternal and newborn care: a non-inferiority study examining delegation of antenatal counseling to lay nurse aides supported by job aids in Benin. BioMed Central. 2011 [Epub ahead of print].

Gessessew A, Ab Barnabas G, Prata N, Weidert K. Task shifting and sharing in Tigray, Ethiopia, to achieve comprehensive emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):28–31.

Donnay F. Maternal survival in developing countries: what has been done, what can be achieved in the next decade. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2000;70(1):89–97.

Barnes-Josiah D, Myntti C, Augustin A. The “three delays” as a framework for examining maternal mortality in Haiti. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(8):981–93.

Browne JL, et al. Criteria-Based Audit of Quality of Care to Women with Severe Pre-Eclampsia and Eclampsia in a Referral Hospital in Accra, Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4).

Igwegbe AO, et al. Improving maternal mortality at a university teaching hospital in Nnewi, Nigeria. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2012;116(3):197–200.

Strand R, et al. Audit of referral of obstetric emergencies in Angola: a tool for assessing quality of care. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2009;13(2).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Grant # 14-107495-000-INP. We acknowledge core funding for the African Population Health Research Center from The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Swedish International Cooperation Agency (Sida).

Authors’ contributions

FMW and CEM conducted the search for the articles, read the abstracts, shortlisted the papers for consideration, and extracted the data for analysis. COI and ASM reviewed and arbitrated on the papers for inclusion. SM and CK contributed to the design of the study. All authors contributed in writing, reviewing, and approving the manuscript for publication. COI is the principal investigator on the grant that supported the development of this review and oversaw the entire process of the review.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 Checklist for the systematic review. (DOC 63 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wekesah, F.M., Mbada, C.E., Muula, A.S. et al. Effective non-drug interventions for improving outcomes and quality of maternal health care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Syst Rev 5, 137 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0305-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0305-6