Abstract

Background

Unregulated care aides provide up to 80 % of direct resident care in nursing homes. They have little formal training, manage high workloads, frequently experience responsive behaviours from residents, and are at high risk for burnout. This affects quality of resident care, including quality of oral health care. Poor quality of oral health care in nursing homes has severe consequences for residents and the health care system. Improving quality of oral health care requires tailoring interventions to identified barriers and facilitators if these interventions are to be effective. Identifying barriers and facilitators from the care aide’s perspective is crucial.

Methods

We will systematically search the databases MEDLINE, Embase, Evidence Based Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, and Web of Science. We will include qualitative and quantitative research studies and systematic reviews published in English that assess barriers and facilitators, as perceived by care aides, to providing oral health care to nursing home residents. Two reviewers will independently screen studies for eligibility. We will also search by hand the contents of key journals, publications of key authors, and reference lists of all the studies included. Two reviewers will independently assess the methodological quality of the studies included using four validated checklists appropriate for different research designs. Discrepancies at any stage of review will be resolved by consensus.

We will conduct a thematic analysis of barriers and facilitators using all studies included. If quantitative studies are sufficiently homogeneous, we will conduct random-effects meta-analyses of the associations of barriers and facilitators with each other, with care aide practices in resident oral health care, and with residents’ oral health. If quantitative study results cannot be pooled, we will present a narrative synthesis of the results. Finally, we will compare quantitative findings to qualitative studies to identify hypothesized associations or effects not yet tested quantitatively.

Discussion

This review will advance the development of effective strategies for improving quality of oral health care and highlight gaps in research on barriers and facilitators to providing oral health care to nursing home residents, as perceived by care aides.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42015032454

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An estimated 70 to 80 % of paid direct care to residents in North American nursing homes is provided by care aides, including the important task of oral health care. However, care aides are a non-professional, largely unregulated work force with little or no formal training [1–5]. Around 90 % of care aides are female, most are over 40 years old, many are foreign-born (21 % in the USA and 60 % in Canada), and almost half speak English as a second language [1, 4, 5]. Care aides often work multiple jobs, and the majority earn less than half of the national median annual earnings (based on US data, where this workforce is best profiled) [5]. Although care aides frequently experience verbal and physical aggressive behaviour from residents with dementia [1, 6], they have insufficient training in dementia care and in managing responsive behaviours of those residents [5]. Relationships and communications between care aides and regulated nurses are often difficult and conflict-laden, negatively impacting job satisfaction and provision of individualized care [7–9]. Workload is high for care aides, with frequent interruptions, and they spend over 40 % of their work time on tasks that last no longer than 3 min [10]. A high workload combined with lack of time for tasks is associated with reduced job satisfaction [11] and burnout [12], which negatively affects staff health and ultimately the quality of care [13].

Providing oral health care to nursing home residents is complex and challenging for all care providers. Care aides often lack knowledge and training in providing proper oral health care to residents [14–17]. More and more residents now enter nursing homes retaining some natural teeth and with more complex prostheses and bridges than in the past, leading to increased or different care needs [18]. Residents with dementia need extra assistance with oral health care, and their responsive behaviours frequently impose additional challenges for care aides [19].

Oral health care practices are sub-standard in nursing homes, including insufficient brushing of teeth or cleaning of dentures for residents needing assistance, using fingers instead of a toothbrush to perform mouth care, not wearing clean gloves during mouth care, using improper tools and substances for mouth care, not looking into residents’ mouths, and not removing food leftovers [20–22]. A Canadian study notes that in their most recent shift, 59 % of the care aides surveyed felt rushed when doing mouth care and 19 % left mouth care undone [23]. Norwegian studies report unacceptable oral hygiene for up to 50 % of dentate residents and up to 30 % of residents with dentures [24, 25]. The Norwegian studies agree with an Australian [26] study that oral hygiene is significantly worse for residents who need assistance with oral health care than for independent residents and worse for residents with responsive behaviours during mouth care than for residents without [24–26].

The consequences are severe. Poor oral health increases health care costs, reduces residents’ quality of life through unnecessary pain and suffering, and elevates the risk of malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, atherosclerosis, and premature death [27–30]. Bad breath, changed dental aesthetics, and altered speech can affect self-image and self-esteem, with serious psychological and social consequences [31, 32]. Caries is present in 41–76 % of dentate nursing home residents [33–40]. Among all residents, 5–17 % have dental pain [36, 40, 41], 32–49 % need periodontal treatment [36, 37, 41], 66–74 % have gingivitis [36, 39], and 3.4 % report gum pain or discomfort [37]. Improved oral health care for nursing home residents is thus urgent. At any given time, around 350,000 older adults live in Canadian nursing homes [42]; the figure for the USA is over 1.3 million [43] and 2.9 million for Europe [44]. The proportion of older adults (65 years or older) who live in nursing homes in Western countries ranges between 3 and 8 % [44, 45], and the demand for nursing home care is expected to increase substantially [44, 46, 47].

Tailoring improvement interventions to previously identified barriers and facilitators is crucial to achieving a desired change [48–50]. Given the central role that care aides play in providing oral health care to nursing home residents, identifying barriers and facilitators for improvement as perceived by this provider group is paramount in designing effective strategies for better quality of oral health care. Our aim is to identify, critically evaluate, and synthesize the available research evidence on the barriers and facilitators, as perceived by care aides, to providing good oral health care to nursing home residents. Our primary research question is the following: Which barriers and facilitators to providing oral health care to nursing home residents do care aides report? Should we be able to identify studies that, in addition to reporting barriers and facilitators, also assess the association of these factors with care aides’ oral health care practices and/or residents’ oral health, we will address the following secondary research questions: How are care aide reported barriers and facilitators to providing oral health care to nursing home residents associated with (a) care aides’ oral health care practices and (b) residents’ oral health?

Methods/design

Review design

We will conduct a systematic mixed-methods synthesis of research [51]. Our review methods and presentation of results will follow the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions [52] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [53]. This protocol followed the PRISMA-P reporting guidelines for systematic review protocols [54] (Additional file 1).

Search strategy

We will search the databases MEDLINE, Embase, Evidence Based Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, and Web of Science. We developed a search strategy combining oral health-related terms with terms related to care providers and residents in residential long-term care facilities (nursing homes) and pre-tested the strategy with an expert scientific librarian for each database (see Additional file 2 for details). We will retrieve all findings available in the respective database without limiting language and year of publication. We will also select three to five key journals and eight to ten key authors based on the number and relevance of their published papers for our research topic. We will search key journal contents and key author publications by hand. Further, we will screen reference lists of the studies included to ensure that we retrieve all the studies relevant to this review.

Data management

We will manage all references in Zotero—an open source literature management software that facilitates cloud-based online collaboration of researchers. We will import all search results including abstracts into Zotero, use this software for title and abstract screening, upload all full texts retrieved from the Zotero database, and carry out the full-text screening using this software. All review team members will receive training in using Zotero prior to the screening, and we will conduct calibration exercises as well as regular team meetings to discuss issues in order to improve the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We will include all types of published studies listed in the databases searched (Table 1): articles published in peer-reviewed journals and “grey” literature such as non-peer-reviewed articles, textbooks, reports, and theses. We will limit our search to empirical studies (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods) that assess barriers and facilitators perceived by care aides to providing oral health care to nursing home residents. In addition to studies only focusing on barriers and facilitators as reported by care aides, we will also include studies quantitatively assessing the association between barriers or facilitators and care aides’ oral health care practices or residents’ oral health outcomes, if the study explicitly notes that it identified barriers and facilitators as perceived by care aides as a first step. Examples of indicators for care aides’ oral health care practices are the following:

-

Proportion of residents on a care unit or in a facility who receive assistance with cleaning their teeth at least once a day

-

Proportion of care aides on a care unit or in a facility who adhere to defined criteria for oral health best practice, such as taking out a resident’s dentures at least once a day, cleaning and rinsing them, and putting them back into the resident’s mouth

-

Proportion of criteria for oral health best practice to which care aides on a care unit or in a facility adhere

Examples of indicators for residents’ oral health outcomes are tooth decay, tooth status, periodontal issues, and oral hygiene status. The studies need to report a quantitative outcome (e.g. correlations, regression parameters, relative risks) to assess the association between identified barriers/facilitators and either care aides’ oral health care practices or residents’ oral health status.

We will include intervention studies with or without control groups if they (a) explicitly assess barriers and facilitators from the perspective of care aides as a first step and (b) evaluate the effects of interventions to address those barriers and facilitators. Control interventions can be either usual care (no control intervention) or any kind of placebo intervention, such as dissemination of written recommendations on how to improve oral health care for nursing home residents.

We will include studies conducted in nursing homes, settings that are referred to by multiple terms across countries and jurisdictions [55] but that can be defined by the following [55–57]:

-

Accommodating mainly older people with complex health and care needs who cannot remain at home or in a supportive living environment

-

Providing 24-h support and assistance with activities of daily living and nursing care

-

Delivering health services over an extended time, often until resident death

We will also include studies conducted in assisted living facilities, i.e. residential facilities providing care to residents who require supportive care, as recent research indicates that residents living in these facilities have functional and health-related limitations similar to nursing home residents [58].

We will include only studies of care aides, also called health care aides; personal care attendants; personal support workers; and continuing care assistants—Hewko et al. [5] identified 56 different titles. We define care aides as formal, paid, unregulated care providers “who provide supportive services and personal assistance to disabled, elderly and/or ill (acute or chronic) individuals requiring either short-term aide or long-term support” [5].

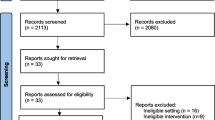

Study screening

After duplicates are removed from retrieved studies, two review team members will independently screen the titles and abstracts of all the studies for inclusion. Each reviewer will assign each study to one of three categories: inclusion, exclusion, or full text needed for decision. At each stage of study identification, the reviewers will resolve discrepancies by consensus. Full texts will be retrieved for all the studies included based on screening of their titles and abstracts and for the studies with insufficient information in titles or abstracts to decide on inclusion. Two review team members will screen full texts independently for inclusion. A hand search of key author publications will be carried out using the same inclusion strategy. One review team member will carry out the key journal hand search, and a second team member will independently check the studies included. Two team members will independently screen the reference lists of all the studies included for any additional relevant studies.

Quality appraisal

Two members of the review team will independently assess the methodological quality of the studies (risk of bias). They will discuss discrepancies until consensus is reached. Results will be discussed in detail by the whole research team for each study. To evaluate study quality, we will use four validated checklists as appropriate to each study’s design, all of which were used and described in detail in previous systematic reviews [11, 59–62].

-

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses—Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool [63]. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid instrument [64–66] that assesses study quality in the categories of definition of an a priori design, study selection and data extraction, literature search, inclusion and exclusion criteria, list of studies included and excluded, characteristics and scientific quality of studies included, appropriateness of conclusions and methods used to combine findings, publication bias, and conflict of interest.

-

Clinical studies with or without a control group and with or without randomized allocation of participants—Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS) [67]. The QATQS is a reliable and valid instrument [67, 68] that assesses studies for selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analyses.

-

Cross-sectional studies—Estabrooks’ Quality Assessment and Validity Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies. This tool, developed based on Cochrane guidelines [69] and other evidence-based criteria [70, 71], assesses the methodological quality of studies through 12 items in the categories of sampling, measurement, and statistical analyses.

-

Qualitative studies—Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist [72]. This checklist assesses whether (a) research aims are clearly stated; (b) qualitative methodology, research design, recruitment strategy, and data collection methods are appropriate; (c) relationships between researchers and participants are adequately considered; (d) ethical issues are sufficiently addressed; (e) data analyses are sufficiently rigorous; (f) findings are clearly stated; and (g) research is valuable overall.

We will rate the overall quality of each study included with a scoring method developed by de Vet et al. [73] and used in those previous systematic reviews. We will calculate the ratio of the obtained score to the maximum possible score, which varies with the checklist used and the number of checklist items applicable. Based on this quality score with a possible range of 0–1, we will rank studies as weak (≤0.50), low moderate (0.51–0.66), high moderate (0.67–0.79), or strong (≥0.80).

Data extraction

One team member will extract study details and record them in an Excel spreadsheet: first author, year of publication, title, journal (or type of study, e.g. thesis, report, textbook), country of study, study purpose(s), study design, study sample (numbers and types of facilities, care aides, and residents included), types and characteristics of interventions/strategies studied (including control conditions, if applicable), types and characteristics of barriers/facilitators, care aides’ oral health care practices, residents’ oral health, other outcomes assessed (including assessment tools, if applicable), and main results. A second team member will double-check the data extraction for each study, with discrepancies resolved by consensus.

Analyses

We will first conduct a thematic analysis of all the studies included [74]. This step is to identify and cluster different types of barriers and facilitators. Next, we will assess how those barriers and facilitators are related to each other and how they are associated with care aides’ practices and with residents’ oral health. We will first review the available quantitative evidence on those associations (i.e. effect sizes of correlations, regression parameters, relative risks), then compare those findings to the qualitative studies included to identify hypothesized associations or effects that have not yet been tested quantitatively. We will statistically pool results of quantitative studies, using random-effects meta-analysis if a sufficient number of quantitative studies report similar outcomes. If so, we will use the I2 statistic [75, 76] including 95 % confidence intervals [77] to assess statistical heterogeneity (variation beyond chance) and inconsistency of study results. As I2 is non-linearly related to the ratio of between- and within-study variances and its expected value depends on the number of included studies (especially for less than ten included studies), we will in addition report H2 (including 95 % confidence intervals), a more robust and unbiased measure for heterogeneity [78]. We expect a rather small number of eligible studies, and we are aware that in this case homogeneity as indicated by each of the included tests may be due to undetected heterogeneity [79]. In case of homogeneity indicated by our homogeneity tests, we will therefore conduct sensitivity analyses, including moderate and large homogeneity assumptions in our models, and compare results to the model based on homogeneity assumption [79]. We will use random-effects models to assess study results, as those models are performing better than fixed effects models in case of heterogeneity and small numbers of included studies [80, 81]. We will also check if study protocols are available for the included studies (especially randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews) and if they were published before recruitment of participants started or before data extraction of included papers was completed, respectively. We will then compare the protocols to the published studies to assess if reporting bias is present. If we are able to include at least ten comparable studies, we will use funnel plots to assess publication bias. In any case, we will consider the year of publication of the included studies (i.e. number of studies included for each year of publication) to determine publication bias, as Kicinski et al. indicate that publication bias is more likely in older compared to more recent studies [82]. If the studies included are too heterogeneous to pool results statistically (e.g. different designs, settings, outcomes), we will construct a narrative synthesis of their outcomes. We will summarize the study designs used, the interventions and control interventions (if applicable) assessed, the resident and care aide outcomes studied, and the effect sizes found. Our pre-tests of the search strategies and our preliminary findings from the title and abstract screenings indicate that we will most likely not be able to synthesize study findings statistically because the number of eligible studies is too small and heterogeneity of study interventions and outcomes is too great.

Discussion

This review will identify, synthesize, and critically evaluate published research studies that assess barriers and facilitators, as perceived by care aides, to providing better oral health care to nursing home residents. To achieve desired changes in oral health care practices, improvement interventions must be tailored to identified barriers and facilitators. Care aides are the main providers of oral health care to nursing home residents; thus, identifying barriers and facilitators from their perspective is crucial to improving quality of oral health care in nursing homes. This review will highlight gaps in the available research on barriers and facilitators to providing better oral health care, as seen by care aides. It will thereby advance the development of effective strategies to improve quality of oral health care for residents of nursing homes.

References

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Carleton HL, Cummings GG, Norton PG. Who is looking after Mom and Dad? Unregulated workers in Canadian long-term care homes. Can J Aging. 2015;34:47–59.

Berta W, Laporte A, Deber R, Baumann A, Gamble B. The evolving role of health care aides in the long-term care and home and community care sectors in Canada. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:25.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment statistics: May 2014 national industry-specific occupational employment and wage estimates, NAICS 623100—nursing care facilities (skilled nursing facilities). 2014. http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_623100.htm#29-0000. Accessed 22 Sep 2015.

Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute (PHI). America’s direct-care workforce. Bronx: PHI; 2013.

Hewko SJ, Cooper SL, Huynh H, Spiwek TL, Carleton HL, Reid S, Cummings GG. Invisible no more: a scoping review of the health care aide workforce literature. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:38.

Zeller A, Hahn S, Needham I, Kok G, Dassen T, Halfens RJ. Aggressive behavior of nursing home residents toward caregivers: a systematic literature review. Geriatr Nurs. 2009;30:174–87.

Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E. Recognition of the health assistant as a delegated clinical role and their inclusion in models of care: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2013;11:3–19.

Caspar S, Cooke HA, O’Rourke N, MacDonald SW. Influence of individual and contextual characteristics on the provision of individualized care in long-term care facilities. Gerontologist. 2013;53:790–800.

Rubin G, Balaji RV, Barcikowski R. Barriers to nurse/nursing aide communication: the search for collegiality in a southeast Ohio nursing home. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17:822–32.

Mallidou AA, Cummings GG, Schalm C, Estabrooks CA. Health care aides use of time in a residential long-term care unit: a time and motion study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:1229–39.

Squires JE, Hoben M, Linklater S, Carleton HL, Estabooks CA. Job satisfaction among care aides in residential long-term care: a systematic review of contributing factors, both individual and organizational. Nurs Res Pract. 2015; Article ID 157924.

Estabrooks CA, Poss JW, Squires JE, Teare GF, Morgan DG, Stewart N, Doupe MB, Cummings GG, Norton PG. A profile of residents in prairie nursing homes. Can J Aging. 2013;32:223–31.

Kerr MS, Laschinger HK, Severin CN, Almost JM, Shamian J. New strategies for monitoring the health of Canadian nurses: results of collaborations with key stakeholders. Nurs Leadersh (Toronto, Ont). 2005;18:67–76. 8–81.

Dharamsi S, Jivani K, Dean C, Wyatt C. Oral care for frail elders: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of long-term care staff. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:581–8.

Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Chen X, Barrick AL, Poole P, Reed D, Mitchell M, Cohen LW. Effect of a person-centered mouth care intervention on care processes and outcomes in three nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1158–63.

Boczko F, McKeon S, Sturkie D. Long-term care and oral health knowledge. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:204–6.

Wardh I, Jonsson M, Wikstrom M. Attitudes to and knowledge about oral health care among nursing home personnel—an area in need of improvement. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e787–92.

McNally ME, Matthews DC, Clovis JB, Brillant M, Filiaggi MJ. The oral health of ageing baby boomers: a comparison of adults aged 45–64 and those 65 years and older. Gerodontology. 2014;31:123–35.

Jablonski RA, Kolanowski AM, Litaker M. Profile of nursing home residents with dementia who require assistance with mouth care. Geriatr Nurs. 2011;32:439–46.

Chami K, Debout C, Gavazzi G, Hajjar J, Bourigault C, Lejeune B, de Wazières B, Piette F, Rothan-Tondeur M. Reluctance of caregivers to perform oral care in long-stay elderly patients: the three interlocking gears grounded theory of the impediments. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:e1–4.

Coleman P, Watson NM. Oral care provided by certified nursing assistants in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:138–43.

Chalmers J, Pearson A. Oral hygiene care for residents with dementia: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:410–9.

Knopp-Sihota JA, Niehaus L, Squires JE, Norton PG, Estabrooks CA. Factors associated with rushed and missed resident care in western Canadian nursing homes: a cross-sectional survey of health care aides. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2815–25.

Zuluaga DJM, Ferreira J, Montoya JAG, Willumsen T. Oral health in institutionalised elderly people in Oslo, Norway and its relationship with dependence and cognitive impairment. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e420–e6.

Willumsen T, Karlsen L, Naess R, Bjorntvedt S. Are the barriers to good oral hygiene in nursing homes within the nurses or the patients? Gerodontology. 2012;29:e748–55.

Philip P, Rogers C, Kruger E, Tennant M. Oral hygiene care status of elderly with dementia and in residential aged care facilities. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e306–11.

MacEntee MI. Muted dental voices on interprofessional healthcare teams. J Dent. 2011;39:S34–40.

Raghoonandan P, Cobban SJ, Compton SM. A scoping review of the use of fluoride varnish in elderly people living in long term care facilities. Can J Dent Hygiene. 2011;45:217–22.

Haumschild MS, Haumschild RJ. The importance of oral health in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:667–71.

MacEntee MI. Missing links in oral health care for frail elderly people. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72:421–5.

Locker D, Slade G. Oral health and the quality of life among older adults: the oral health impact profile. J Can Dent Assoc. 1993;59:830–3. 7–8, 44.

Slade GD, Spencer AJ, Locker D, Hunt RJ, Strauss RP, Beck JD. Variations in the social impact of oral conditions among older adults in South Australia, Ontario, and North Carolina. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1439–50.

Wyatt CC. Elderly Canadians residing in long-term care hospitals: Part II. Dental caries status. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:359–63.

Shimazaki Y, Soh I, Koga T, Miyazaki H, Takehara T. Relationship between dental care and oral health in institutionalized elderly people in Japan. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31:837–42.

Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Fuss JM, Spencer AJ, Hodge CP. Caries experience in existing and new nursing home residents in Adelaide, Australia. Gerodontology. 2002;19:30–40.

Matthews DC, Clovis JB, Brillant MGS, Filiaggi MJ, McNally ME, Kotzer RD, Lawrence HP. Oral health status of long-term care residents: a vulnerable population. J Can Dent Assoc. 2012;78:c3.

Arpin S, Brodeur JM, Corbeil P. Dental caries, problems perceived and use of services among institutionalized elderly in 3 regions of Quebec, Canada. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:807.

Maupome G, Wyatt CC, Williams PM, Aickin M, Gullion CM. Oral disorders in institution-dwelling elderly adults: a graphic representation. Spec Care Dentist. 2002;22:194–200.

Patrick DL, Murray TP, Bigby JA, Auerbach J, Mullen J, Johnson DE, Bethel LA. The Commonwealth’s high-risk senior population: results and recommendations from 2009 statewide oral health assessment. Boston: Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Office of Oral Health; 2010.

Porter J, Ntouva A, Read A, Murdoch M, Ola D, Tsakos G. The impact of oral health on the quality of life of nursing home residents. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:102.

Adegbembo AO, Leake JL, Main PA, Lawrence HL, Chipman ML. The effect of dental insurance on the ranking of dental treatment needs in older residents of Durham Region’s homes for the aged. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:412–8.

Statistics Canada. Living arrangements of seniors: families, households and marital status. Structural type of dwelling and collectives, 2011 Census of Population. 2011.

Harrington C, Carrillo H, Garfield R. Nursing facilities, staffing, residents and facility deficiencies, 2009 through 2014. Menlo Park: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015.

European Commission. Long-term care for the elderly: provisions and providers in 33 European countries. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2012.

Gore DR. The use of dental sealants in adults: a long-neglected preventive measure. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8:198–203.

Alzheimer Society of Canada. Rising tide: the impact of dementia on canadian society. Toronto, ON: Alzheimer Society of Canada; 2010.

Congress of the United States - Congressional Budget Office. Rising demand for long-term services and supports for elderly people. Washington: CBO; 2013.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N, Wensing M, Fiander M, Eccles MP, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:Cd005470.

Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernández ME. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Wiley; 2011.

Hulscher M, Wensing M, Grol R. Multifaceted strategies for improvement. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Davis DA, editors. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. 2nd ed. Chinchester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. p. 278–87.

Harden A. Mixed-methods systematic reviews: integrating quantitative and qualitative findings. Focus. 2010;2010:1–8.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]: the Cochrane Collaboration. 2015.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, Group P-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

McGregor MJ, Ronald LA. Residential long-term care for Canadian seniors: nonprofit, for-profit or does it matter? Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy; 2011.

Jansen I, Murphy J. Residential long-term care in Canada: our vision for better seniors’ care. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Union of Public Employees; 2009.

Canadian Healthcare Association. New directions for facility-based long term care. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Healthcare Association; 2009.

Hogan DB, Amuah JE, Strain LA, Wodchis WP, Soo A, Eliasziw M, Gruneir A, Hagen B, Teare G, Maxwell CJ. High rates of hospital admission among older residents in assisted living facilities: opportunities for intervention and impact on acute care. Open Med. 2014;8:e33–45.

Kajermo KN, Boström AM, Thompson DS, Hutchinson AM, Estabrooks CA, Wallin L. The BARRIERS scale—the barriers to research utilization scale: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2010;5:32.

Squires J, Estabrooks C, Gustavsson P, Wallin L. Individual determinants of research utilization by nurses: a systematic review update. Implement Sci. 2011;6:1.

Squires JE, Hutchinson AM, Boström AM, O’Rourke HM, Cobban SJ, Estabrooks CA. To what extent do nurses use research in clinical practice? A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:21.

Hoben M, Buscher I, Berendonk C, Quasdorf T, Riesner C, Wilborn D. Scoping review of nursing-related dissemination and implementation research in German-speaking countries: mapping the field. Int J Health Prof. 2014;1:34–49.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

Shea BJ, Bouter LM, Peterson J, Boers M, Andersson N, Ortiz Z, Ramsay T, Bai A, Shukla VK, Grimshaw JM. External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR). PLoS One. 2007;2:e1350.

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J, Henry DA, Boers M. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1013–20.

Kang D, Wu Y, Hu D, Hong Q, Wang J, Zhang X. Reliability and external validity of AMSTAR in assessing quality of TCM systematic reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012.

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–84.

Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:12–8.

Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane reviewers’ handbook 4.1.4 (October 2001). Oxford: The Cochrane Library; 2001.

Kmet L, Lee R, Cook L. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton: Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2004.

Khan KS, ter Riet G, Popay J, Nixon J, Kleijnen J. Stage II conducting the review: phase 5 study quality assessment. In: Centre of Reviews and Dissemination UoY, editor. Undertaking systematic reviews of research effectiveness CDC’s guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. 2001. p. 1–20.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP checklists. 2013. http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8. Accessed 02 Apr 2016.

de Vet HCW, de Bie RA, van der Heijden GJMG, Verhagen AP, Sijpkes P, Knipschild PG. Systematic reviews on the basis of methodological criteria. Physiotherapy. 1997;83:284–9.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

Ioannidis JP, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2007;335:914–6.

Mittlbock M, Heinzl H. A simulation study comparing properties of heterogeneity measures in meta-analyses. Stat Med. 2006;25:4321–33.

Kontopantelis E, Springate DA, Reeves D. A re-analysis of the Cochrane Library data: the dangers of unobserved heterogeneity in meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69930.

Brockwell SE, Gordon IR. A comparison of statistical methods for meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2001;20:825–40.

Kontopantelis E, Reeves D. Performance of statistical methods for meta-analysis when true study effects are non-normally distributed: a comparison between DerSimonian-Laird and restricted maximum likelihood. Stat Methods Med Res. 2012;21:657–9.

Kicinski M, Springate DA, Kontopantelis E. Publication bias in meta-analyses from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Stat Med. 2015;34:2781–93.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Carole Estabrooks for her support for this study.

Funding

This research has been supported by intramural funds from the School of Dentistry, University of Alberta, and the Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta; MH holds an Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions (AIHS) Post Doctoral Fellowship. None of the funders has played any role in developing the systematic review protocol.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MH and MNY developed the research question and the systematic review design, planned and designed the study protocol, and led the systematic review project. MH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HH, TX, AK, and NK assisted with the drafting parts of the manuscript and carried out the abstract and full-text screening. All authors critically read and commented on the manuscript and have approved its submission.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA-P checklist. The checklist is composed of recommended items to address in a systematic review protocol. (PDF 218 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search strategy. The file gives a list of search terms/keywords to be used for this protocol. (PDF 133 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoben, M., Hu, H., Xiong, T. et al. Barriers and facilitators in providing oral health care to nursing home residents, from the perspective of care aides—a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 5, 53 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0231-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0231-7