Abstract

Wireless devices’ energy efficiency and spectrum shortage problem has become a key concern worldwide as the number of wireless devices increases at an unparalleled speed. Wireless energy harvesting technique from traditional radio frequency signals is suitable for extending mobile devices’ battery life. This paper investigates a cognitive radio network model where primary users have their specific licensed band, and secondary users equipped with necessary hardware required for energy harvesting can use the licensed band of the primary user by smart sensing capability. Analytical expressions for considered network metrics, namely data rate, outage probability, and energy efficiency, are derived for uplink and downlink scenarios. In addition, optimal transmission power and energy harvesting power are derived for maximum energy efficiency in downlink and uplink scenarios. Numerical results show that outage probability improves high transmission power in the downlink scenario and high harvested power in the uplink scenario. Finally, the result shows that energy efficiency improves using optimum transmission power and energy harvesting power for downlink and uplink scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The innovation of emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Cloud computing, and the recent growth of digital communication systems beyond 5G has contributed most to an ever-expanding number of wireless or wired devices [1]. These devices include smart homes, smart appliances, smart agriculture, IoT-based portable health monitoring systems, embedded system for mobile phones [2]. These gadgets require the battery to function smoothly during operation. Consequently, the battery needs to be frequently recharged as the performance duration of the battery is limited. This has become a serious concern as many users, such as healthcare, military, and other crucial users, cannot afford downtime as those users are connected to a thousand other users in real-time. As the number of devices is rapidly increasing, spectrum shortage and energy scarcity have become a significant concern for researchers worldwide [3]. The introduction of cognitive radio (CR) technology, which includes wireless energy harvesting (WEH) and smart spectrum sensing, can be a great solution to the existing resource shortage problem [4].

WEH is an emerging new technology where any device equipped with the necessary hardware can harvest energy from various sources such as solar, thermoelectric, radio frequencies (RF), and others [5]. Recently, WEH from RF devices has been powerfully attracted by the focus of researchers worldwide. IoT technology will significantly benefit from WEH; the battery of IoT devices will not be replaced or recharged frequently. Wireless devices can function longer than the expected lifetime using smart WEH techniques, despite being equipped with a traditional battery [6, 7]. On the other hand, CR can intelligently switch between channels or allocate secondary users (SU) to use the licensed frequency bands of primary users (PU) based on smart sensing capability [8]. Typically, SU can detect spectrum holes (idle time slot of PU) using spectrum sensing and efficiently transmit energy and information within the given phase. However, SUs are not allowed to communicate when PU is active in the transmission phase to improve the quality of service of licensed PU and reduce the interference effect. With a WEH-enabled CR network, SU, such as mobile devices, can harvest energy from RF signals generating from the PU transmitter or base station via smart detection. To effectively utilize PU’s signal, both energy harvesting and information can be transferred between PU and SU via simultaneous wireless and information power transfer. Our primary objective is to study the performance analysis of WEH for bidirectional communication in the CR network in this research.

1.1 Related works

WEH is an emerging new technology where any device equipped with the necessary hardware can harvest energy from various sources such as solar, thermoelectric, radio frequencies (RF), and others [5]. Recently, WEH from RF devices has been powerfully attracted by the focus of researchers worldwide. IoT technology will significantly benefit from WEH; the battery of IoT devices will not be replaced or recharged frequently. Wireless devices can function longer than the expected lifetime using smart WEH techniques, despite being equipped with a traditional battery [6, 7]. On the other hand, CR can intelligently switch between channels or allocate secondary users (SU) to use the licensed frequency band; recently, energy harvesting (EH) has emerged as a promising solution provider for traditional wireless communication devices. Newly designed EH circuits can transform RF from conventional sources to usable direct current (DC) power. Researchers are now working on various EH issues of CR networks, such as spectrum sensing, power allocation, and throughput, to find the optimal solution for CR networks.

1.1.1 Time switching technique

Park et al. presented a novel spectrum scheme to increase the overall throughput of CR networks focus on EH circuit on PU and secondary transmitter. Authors have been derived the detection threshold limit for satisfying the energy constraint concerning maximum total throughput [9]. Bhoumick et al. presented mathematical expression of detection sensing of EH concerning throughput of CR network. Utilization of reused spectrum and comparison between noise powers based on energy detector is also analyzed here [10]. Power allocation strategy and best channel selection scheme for SU is presented in [11], where authors derived the closed-form expression of packet loss probability and packet delay of SU.

Obaid and Fernando developed a new model to provide WEH in CR network, which exploits media access control (MAC) protocol to increase efficiency in CR network [12]. Simulation result indicates that WEH needs to be extracted from high-powered devices such as TV or radio systems instead of low-powered small devices suggested by researchers. The sensing interval problem of free and busy channel in EH-based CR network was formulated in [13] where removed transmitted energy in a time slot acted as a target function. Afterward, the Markov chain model was developed for each sensing interval to find the energy state transition probability. The work in Malek et al. [14] examined the performance of a multiple-input single-output (MISO) network where SU devices are equipped with multiple antennas to harvest energy from the hybrid base station and existing PU network. Besides, the authors derived the closed-form expressions of outage probability of SU network and introduced an optimization problem to reduce the SU outage probability for transmission power. Novel hybrid underlay channel model in secondary SU network with EH capability was studied in Tayel et al. [15]. Besides, closed-form expression for energy transmission and outage probability for the underlay model in Rayleigh fading channel was derived in their works of primary users (PU) based on smart sensing capability [8]. Typically, SU can detect spectrum holes (idle time slot of PU) using spectrum sensing and efficiently transmit energy and information within the given phase. However, SUs are not allowed to communicate when PU is active in the transmission phase to improve the quality of service of licensed PU and reduce the interference effect. With a WEH-enabled CR network, SU, such as mobile devices, can harvest energy from RF signals generating from the PU transmitter or base station via smart detection. To effectively utilize PU’s signal, both energy harvesting and information can be transferred between PU and SU via simultaneous wireless and information power transfer. Our primary objective is to study the performance analysis of WEH for bidirectional communication in the CR network in this research.

1.1.2 Power splitting technique

Liu et al. presented a multiple spectrum sensing and EH framework model where the sensing slot is divided into various sensing and EH sub-slots. The joint optimization problem has been discussed for increasing the throughput of SU detecting the false alarm conditions [16]. Son et al. conducted studies to measure the performance of power splitting ratio, and power-sharing coefficient in PU and SU in CR network [17]. In [18], authors explored channel capacity, transmission probability, optimal transmission power to maximizes EH, and spectrum sensing in the CR network. The work in [19] enhanced the energy harvesting of transmitted signal of antennas by selecting the optimal value of power splitting factor for energy harvesting, information transfer, and blocked signal probability. Furthermore, the outage problem is also derived for MISO and single-input multiple-output (SIMO) technique to examine physical layer security for both models.

1.1.3 Both time and power splitting techniques

Ghosh et al. presented a comparative analysis of one-way and bidirectional communication on RF-EH relay in CR networks [20]. The experiment results indicate that hybrid power time-switching relaying (HPTSR) performs better than power splitting relay (PSR) around \(35\%\). In [21], Sabuj and Hamamura illustrated the performance of RF energy harvesting in a random CR network where transmitter and receiver are deployed randomly. It is has been shown that outage probability is inversely proportional with transmission power, and harvested DC power improves with higher transmission power. They recommended RF-EH model as a good alternative for the longevity of wired battery devices. The authors in [22] studied particle swarm optimization algorithm for EH-based hybrid SWIPT CR network with bidirectional communication. Their primary objective was to increase the total system throughput and maximum energy efficiency of the network. Furthermore, in [23], authors studied the energy efficiency optimization model for bidirectional energy harvesting sensor networks. They introduced fractional programming and alternative search methods to achieve high transmission power and resolve the power constraint problem of relay and sensor nodes.

1.2 Scope and contributions

In the previously mentioned literature in [20], the work investigated the minimum outage probability. However, this paper investigates the energy efficiency of EH in CR for bidirectional communication. An EH-based CR network model is introduced here where SU can simultaneously transfer information and harvest energy from PU during assigned time slots. The significant contribution of this paper is presented as follows:

-

This paper introduces an EH-based CR network model for bidirectional communication between mobile user equipment (MUE) and base station (BS) for simultaneous information and energy transfer. The achievable data rate between BS and MUE for both uplink and downlink scenarios is studied here.

-

We also derive the outage probability and energy efficiency of the existing CR network for uplink and downlink communication systems.

-

Furthermore, we derive the optimal transmission power and energy harvesting power expressions for maximum energy efficiency in a given CR network.

-

Finally, the numerical results provide a practical guideline that the proposed bidirectional EH-based CR network model can significantly improve the highlighted existing problems by various system parameters, such as transmission power of BS, harvested power, and distance between MUE and BS. The simulation results also reveal that the energy efficiency of the proposed scheme is significantly improved compared to optimal transmission power and energy harvesting power.

Symbols and their short description are presented in Table 1 to understand the paper easily. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents our proposed CR network model. Section 3 obtains the theoretical expression of our proposed model’s data rate, outage probability, and energy efficiency. Also, maximum energy efficiency is discussed for uplink and downlink scenarios. Numerical results are discussed in Sect. 4. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes the paper.

2 Design and modeling of network architecture and assumptions

2.1 Network model

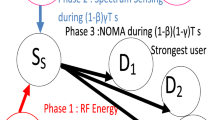

A CR network shown in Figure 1 is a graphical representation of bidirectional communication system between mobile user equipment (MUEFootnote 1) and base station (BS[1]) with the presence of primary transmitter (PT). In the downlink scenario, BS communicates with MUE. In the uplink scenario, MUE communicates with BS. It is also assumed that MUE is capable of harvesting energy from radio signals transmitted from BS. Both MUE and BS are equipped with a single transceiver for sending and receiving data.

2.2 Time-slot and sensing

Figure 2 is a frame structure of information and energy transfer between MUE and BS. It can be observed that for one frame duration, time slot T is separated into three parts according to time-switching method: \(\tau _{1}T\), \(\tau _{2}T\) and \((1-\tau _{1}-\tau _{2})T\), where \(0 \le (\tau _{1}+\tau _{2}) \le 1\). During the first transmission phase, BS transmits its signal to MUE during \(\tau _{1}T\) period. Subsequently, in second phase, spectrum sensingFootnote 2 is applied over \(\tau _{2}T\) period at the MUE. It is assumed that during \(\tau _{1}T\), a constant power P is used for energy harvesting from BS to MUE and remaining \(P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}-P\) power is used for information transfer from BS to MUE according to power-splitting method [21, 26]. And in the last phase, information is sent from MUE to BS during \((1-\tau _{1}-\tau _{2})T\) period.

2.3 Channel model

In the considered CR network, the presence of fading channel model is acknowledged here. Due to all links, fading coefficients are assumed as independent identical random variables with zero mean and unit variance (i.e. \(g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}} \sim {\mathcal {CN}} (0,1)\), \(g_{BS} \sim \mathcal {CN} (0,1)\), \(h_{p1} \sim \mathcal {CN} (0,1)\) and \(h_{p2} \sim \mathcal {CN} (0,1)\)). Here, the symbol \(g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) and \(g_{BS}\) refer to the fading coefficient link from MUE to BS and the fading coefficient link from BS to MUE. Also, the symbol \(h_{p1}\) and \(h_{p2}\) refer to the fading coefficient link from PT to MUE and the fading coefficient link from PT to BS.

3 Mathematical modeling and definition

3.1 Definition of metric

3.1.1 Data rate

Data rate can be defined as the speed at which information is transferred between MUE and BS or vice versa in CR network.

3.1.2 Outage probability

Outage probability can be described as probability of received signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio (SINR) at any given node is lower than the predefined threshold for that particular receiver.

3.1.3 Energy efficiency

Energy efficiency is the ratio between successful data rate to transmission power and total circuit power consumption in a device (e.g. MUE and BS).

3.2 Downlink scenario

Signal received for transmitting information and energy harvesting at MUE from BS can be denoted as

where \(P_{BS}\) denotes the transmission power of BS, \(g_{BS}\) is the channel gain from BS to MUE, \(x_{BS}\) represents transmit signal of BS with zero mean and \(\text {E}[\left| x_{BS} \right| ^{2}] = 1\), \(d_{s}\) is the distance between BS and MUE, \(P_{p}\) is transmission power of PT, \(d_{p}\) denotes the distance from PT to MUE, \(h_{p1}\) is channel gain between PT to MUE, \(x_{p}\) is transmit signal of PT with zero mean and \(\text {E}[\left| x_{p} \right| ^{2}] = 1\), \(n_{a_{1}}\) and \(n_{conv}\) represents antenna noise for signal transmission from BS to MUE and baseband conversion noise, respectively.

Subsequently, received signal power at MUE from BS using Eq. (1) can be calculated as:

where \(0 < \Psi _{1} \le 1\) denotes the energy conversion efficiency of radio signal-to-power depending on the harvesting circuitry.

During \(\tau _{1}T\) period, the received power from BS is divided into two parts: continuous power P is used for energy harvesting and remaining power \((P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}-P)\) is used for information transfer from BS to MUE according to power-splitting method [21, 26]. Accordingly, SINR at MUE from BS can be defined as

where \(\sigma _{s}^{2}\) is denoted as \(\sigma _{s}^{2} = \sigma _{n_{a_{1}}}^{2}+\sigma _{conv}^{2}\).

From Eq. (3), data rate from BS to MUE can be defined as

From Eq. (4), outage probability from BS to MUE can be derived as follows

where \(R_{1}\) is defined as the target data rate. Energy efficiency of BS can be expressed as

3.3 Maximum energy efficiency in downlink

To find the optimal transmission power in terms of energy efficiency, we set the derivative of Eq. (6) with respect to \(P_{BS}\) equal to zero leading to

By taking the first-order derivative of Eq. (6) with respect to \(P_{BS}\), we get:

where a denotes \(a = \frac{P-\frac{\Psi _{1} P_{BS} g_{BS}^{2}}{(d_{s})^{\alpha }}}{\sigma _{s}^{2} + \frac{P_{p}h_{p1}}{(d_{p})^{\alpha }}}\) and q indicates \(q = \sigma _{s}^{2}+\frac{P_{p} h_{p1}}{(d_{p})^{\alpha }}\).

By applying Lambert method in Eq. (8), we can write

where \(\beta _1 = \frac{\Psi _{1} P_{BS} g_{BS}^{2} +(d_{s})^{\alpha } (q-P)}{(d_{s})^{\alpha } q} e^{-1}\) and \(W\left( \cdot \right)\) is Lambert function.

Finally, after some mathematical manipulation in Eq. (9), \(P_{BS}\) can be written as

One can see that Eq. (10) depends on Lambert function \(W\left( \beta _1\right)\). \(W\left( \beta _1\right)\) has exactly one real solution for all real \(\beta _1 \ge 0\). \(W\left( \beta _1\right)\) has exactly two real solutions for \(-e^{-1}< \beta _1 < 0\), where the larger solution is considered for the upper bound of optimal power and the smaller solution is considered for the lower bound of optimal power [27]. In Eq. (10), optimal transmission power increases with \(d_s\), so \(P_{BS}\) can be expressed as

where \(P_{BST}\) is the total power budget of BS. For the maximum energy efficiency, we put \(P_{BS}^{\star }\) in Eq. (6).

3.4 Uplink scenario

Signal received at BSFootnote 3 from MUE can be written as

where \({P-{P_{s}}}\) denotes the transmission power of signal carrying information from MUE to BS, where \(P_{s}\) represents the spectrum sensing power. \(g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) is the channel gain from MUE to BS, \(x_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) represents transmit signal of MUE with zero mean and \(\text {E}[\left| x_{\mathrm{{MUE}}} \right| ^{2}] = 1\), \(d_{s}\) is the distance between BS and MUE, \(P_{p}\) is transmission power of PT, \(d_{k}\) denotes the distance from PT to BS, \(h_{p2}\) is channel gain between PT to BS, \(x_{p}\) is transmit signal of PT with zero mean and \({\text {E}}[\left| x_{p} \right| ^{2}] = 1\), \(n_{a_{2}}\) and \(n_{conv}\) represent antenna noise for signal transmission from BS to MUE and baseband conversion noise, respectively.

Similarly, received signal power at BS from MUE using Eq. (12) can be calculated as

where \(0 < \Psi _{2} \le 1\) denotes the energy conversion efficiency.

Consequently, SINR at BS from MUE can be obtained as

Furthermore, data rate between MUE and BS from Eq. (14) can be defined as

From Eq. (15), outage probability from MUE to BS can be derived as follows

where \(R_{2}\) is threshold data rate. Energy efficiency of MUE can be expressed as

3.5 Maximum energy efficiency in uplink

To find constant power in terms of energy efficiency, we set the derivative of Eq. (17) with respect to P equal to zero leading to

By taking the first-order derivative of Eq. (17), we get

where b is defined as \(b = 1 + \frac{\Psi _{2} (P - P_{s}) g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}^{2}}{(d_{s})^{\alpha }(\sigma _{s}^{2} + \frac{P_{p} h_{p2}}{(d_{k})^{\alpha }})}\) and y is calculated as \(y = \sigma _{s}^{2}+\frac{P_{p} h_{p2}}{(d_{k})^{\alpha }}\) and \(c = \frac{(1-\Psi _{2})(P - P_{s}) g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}^{2} + g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}^{2} P_{\mathrm{{cir}}}^{MUE}-y(d_{s})^{\alpha }}{\Psi _{2} (P-P_{s}) g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}^{2}+ y (d_{s})^{\alpha }}\).

By applying Lambert method in Eq. (19), we can write

where \(\beta _2 = \frac{(1-\Psi _{2})(P - P_{s}) g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}^{2} + g_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}^{2} P_{\mathrm{{cir}}}^{MUE}-y(d_{s})^{\alpha }}{y (d_{s})^{\alpha }} e^{-1}\).

Finally, after some mathematical manipulation in Eq. (20), \(P^{\star }\) can be expressed as

One can see that Eq. (21) depends on Lambert function \(W\left( \beta _2\right)\). \(W\left( \beta _2\right)\) has exactly one real solution for all real \(\beta _2 \ge 0\). \(W\left( \beta _2\right)\) has exactly two real solutions for \(-e^{-1}< \beta _2 < 0\), where the larger solution is considered for the upper bound of optimal power and the smaller solution is considered for the lower bound of optimal power [27]. In Eq. (21), optimal harvested power increases with \(d_s\), so P can be expressed as

where \(P_{M}\) is the maximum harvested power. For the maximum energy efficiency, we put \(P^{\star }\) in Eq. (17).

4 Simulation results and discussion

The performance in terms of data rate, outage probability, energy efficiency, and optimization technique is evaluated in this section. Some parameters are changed depending on the figure which is mention in the figure. All simulations are executed by considering \(\alpha = 4\), \(\tau _{1} = 0.4\), \(\tau _{2} = 0.2\), \(\Psi _{1} = 0.65\), \(\Psi _{2} = 0.65\), \(R_1 = 1\), \(R_2 = 1\), \(d_p = 1800\) m, \(d_k = 2000\) m, \(d_s = 100\) m, \(P_{p} = 120\) dBm, \(P_{\mathrm{{cir}}}^{BS} = 120\) W, \(P_{\mathrm{{cir}}}^{MUE} = 1\) W, and \(\sigma _{s}^{2} = - 174\) dBm. Monte Carlo simulations are run over 10,000 times for the different fading coefficients.

4.1 Downlink analysis

4.1.1 Data rate

Figure 3 shows that data rate is a monotonically increasing function of transmission power. Data rate shows an abysmal performance almost close to zero up to 5 dBm transmission power. After that, with increasing transmission power, data rates take a sharp rise and reach the maximum value of 3.367 bps/Hz at 40 dBm transmission power for \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\). As transmission power increases, more power is assigned for information transfer between BS and MUE. We can observe an improvement of \(90.12\%\) in data rate for varying the transmission power from 25 dBm to 35 dBm for \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\). Compared between \(P=0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) and \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\), \(P=0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) is better because of more power (\(P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}-P\)) is allocated for information transfer. The theoretical and simulation results are compared in Fig. 3. The simulation result is fairly close to the theoretical result, which validates in Eq. (4).

Figure 4 represents the comparative analysis of data rate versus distance between BS and MUE. It is observed that the data rate continues to drop gradually for the increasing distance between BS and MUE for downlink communication. The figure shows that the maximum achievable data rate is 12.93 bps/Hz when the distance is almost zero between BS and MUE. This can be explained by the fact that as distance increases between BS and MUE, the SINR of the downlink system gets worse. For a variation of 100 m to 150 m, we notice a decrease of 2.313 bps/Hz to 1.418 bps/Hz which is \(38.69\%\) decrease for \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) in data rate.

4.1.2 Outage probability

Figure 5 describes the performance of outage probability for different values of transmission power. Initially, the outage probability of the system for downlink communication stays constant at its peak value of 1 and then drops quickly as the transmission power increase in the range of \(10-40\) dBm for both the curves. \(P=0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) is lower outage probability in comparison with \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\). This is because more power is allocated for information transfer in \(P=0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\). As a result, SINR will rise, which eventually results in a low outage probability. The simulation result is fairly close to the theoretical result, which validates in Eq. (5).

The result of the outage probability concerning the distance between BS and MUE is shown in Fig. 6. Here, we can observe that outage probability is steadily increasing with increasing distance. The explanation here is that when distance is less between BS and MUE, the path loss is low between BS and MUE during downlink communication. It can be seen that \(P=0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) shows a lower outage performance decrease of \(18.10\%\) in comparison with \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) for a distance of 200 m between BS and MUE.

4.1.3 Energy efficiency

Figure 7 exhibits the energy efficiency of our given system of bidirectional communication versus transmission power. Here, we can observe that the energy efficiency rises with increasing transmission power and reaches the optimal value of 0.0279 bps/Hz/W and 0.0257 bps/Hz/W for \(P = 0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) dBm and \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) dBm, respectively. It can be further observed that \(P = 0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) dBm shows better performance in terms of energy efficiency than \(P= 0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) dBm. For consideration of \(P_{BS} = 30\) dBm, there is 13.32% increase in energy efficiency for \(P= 0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) dBm. The explanation here is that when P is low and \(P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}} - P\) is high, so the data rate and energy efficiency are high based on Eq. (6).

Figure 8 illustrates the performance of energy efficiency for transmiting power for both original and optimal graphs based on Eqs. (6) and (11). From the figure, it is clear that the optimal curve remains a constant value of 0.2855 bps/Hz/W for various transmission power. However, the original curve rises gradually with increasing transmission power and reaches the maximum 0.2798 bps/Hz/W at 40 dBm. There is an improvement of \(48.95\%\) in terms of energy efficiency in the optimal curve than the original for 30 dBm power.

Figure 9 shows the effect of energy efficiency for distance for the downlink communication. From the figure, we can observe that both curves were linearly decreasing with respect to distance. However, \(P=0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) curve shows better performance in terms of energy efficiency. For example, \(P=0.2*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) is an improvement of \(6.85\%\) compared with \(P=0.5*P_{\mathrm{{MUE}}}\) for 50 m distance between BS and MUE.

Figure 10 displays the energy efficiency versus distance for downlink communication in a bidirectional communication system for original and optimal curves based on (6) and (11). As we can observe from the figure, the optimal curve gradually decreases as a distance function and reaches a minimum value of 0.01276 bps/Hz/W at 300 m distance. Similarly, the original curve shows the minimum value of 0.003449 at 300 m. For a variation of 100 m to 150 m, we observe a decrease of \(35.24\%\) for the original curve and subsequently \(20.53\%\) decrease for the optimal curve. The performance of the optimal curve is better than the original curve in the simulation because of transmission power based on (11) which ultimately leads to an increase in energy efficiency.

4.2 Uplink analysis

4.2.1 Data rate

Figure 11 shows that data rate is a monotonically increasing function of harvested power. Data rate shows an abysmal performance almost close to zero up to 5 dBm harvested power. After that, with increasing, harvested power data rate takes a sharp rise and reaches the maximum value of 2.29 bps/Hz and 2.51 bps/Hz at 30 dBm harvesting power for \(P_{s}=0.5*P\) and \(P_{s}=0.2*P\), respectively. We can observe an improvement of \(85.84\%\) in data rate for varying the harvesting power from 15 dBm to 20 dBm for \(P_{s}=0.5*P\). This is because \(P_s\) is low and \(P - P_s\) is high. Thus, it improves the data rate. Moreover, the theoretical result exactly matches the simulation result.

Figure 12 represents the comparative analysis of data rate versus distance between BS and MUE. It is observed that the data rate continues to drop gradually for the increasing distance between BS and MUE for uplink communication. The figure shows that the maximum achievable data rate is 12.93 bps/Hz when the distance is almost zero between MUE and BS. This can be explained by the fact that as distance increases between BS and MUE, the SINR of the uplink system gets worse. Thus, the data rate tends to drop between BS and MUE. For a variation of 100 m to 150 m, we notice a decrease of \(38.97\%\) for \(P_{s} = 0.5*P\) in terms of data rate.

4.2.2 Outage probability

Figure 13 describe the performance of system outage for different value of harvested power. Initially, the outage probability of the system for uplink communication remains constant and then drops quickly as the harvested power increase in the range of \(11-30\) dBm for both the curves. Almost \(5\%\) more harvested power is needed for \(P_{s}=0.5*P\) to gain the outage probability of 0.55 in comparison with \(P_{s}=0.2*P\). Due to higher harvested power, more power is allocated for information transfer in the system. As a result, information can be transmitted easily to BS, and SINR will rise, resulting in low outage probability.

The result of outage probability against the distance between BS and MUE is shown in Fig. 14. Here, we can observe that outage probability increases with increasing distance. This is because the path loss is low for a short distance. For \(P_s=0.5*P\), outage probability reaches the maximum value of 1 at 260 m and when \(P_s=0.2*P\) outage probability gets it maximum value of 1 at 280 m. Because, \(P_s\) is low where as the \(P - P_s\) is high, so it covers more distance.

4.2.3 Energy efficiency

Figure 15 depicts the performance of energy efficiency with respect to harvested power in the bidirectional system for uplink communication. From the figure, it can be observed that energy efficiency increases with increasing harvested power. As harvested power increases and reaches the maximum value of 0.4651 bps/Hz/W and 0.4411 bps/Hz/W at 30 dBm for \(P_{s}=0.5*P\) and \(P_{s}=0.2*P\), respectively. This is because \(P_s\) is high and \(P-P_s\) is low. Therefore, \(P - P_s\) increases, the energy efficiency decreases based on Eq. (17). In addition, the theoretical result exactly matches the simulation result.

Regarding Fig. 15, Fig. 16 presents the effect of energy efficiency with varying harvesting power and performance comparison also shown between original and optimal curve based on (17) and (22). The figure shows that the optimal curve, an extended version of (17), remains a constant value of 0.440 bps/Hz/W for various harvested power. However, the original curve rises gradually with increasing harvesting power and reaches the maximum value of 0.440 bps/Hz/W, which matches the optimal value at 30 dBm. This is because maximum power is allocated for data transmission at 30 dBm. For a variation of 15 dBm to 20 dBm harvested power, the original curve shows an improvement of \(71.23\%\).

Figure 17 represents the energy efficiency of the given system for uplink communication with respect to various distances. The figure shows that the energy efficiency continues to fall with increasing distance between BS and MUE. For a distance of 50 m, we can see an improvement of \(19.98\%\) for \(P_{s}=0.5*P\) in comparison with \(P_{s}=0.2*P\). \(P_{s}=0.5*P\) is higher energy efficiency in comparison with \(P_{s}=0.2*P\). This is because \(P_s\) is high and \(P-P_s\) is low. Therefore, \(P - P_s\) increases, the energy efficiency decreases based on Eq. (17). For the high distance between BS and MUE, the data rate drops significantly for information transfer as the necessary power allocated for information transfer is lower than the predetermined threshold limit. For decreasing data rates, the energy efficiency of a given system will also drop.

Figure 18 exhibits a performance comparison between original and optimal curve for energy efficiency versus distance for the uplink communication system. We can observe that both curves decrease for distance. The optimal curve shows better performance in terms of energy efficiency of \(19.15\%\) increase for 50 m distance between BS and MUE. However, original and optimal performance are the same after 126 m. This is because maximum harvested power is allocated for data transmission based on (22) at 126 m and then is allocated the same power for both scheme. Performance of optimal curve is better than the original curve in the simulation because the variation of harvested power based on (20) which ultimately leads to increase in energy efficiency [29, 30].

5 Conclusion and future works

Energy harvesting from RF signals is now considered a promising new solution for the longevity of battery life in traditional wireless devices. This paper introduces a WEH technique based on the CR network for bidirectional communication. The mathematical expression of data rate, outage probability, and energy efficiency for downlink and uplink scenarios is presented here. In addition, maximum energy efficiency is obtained for optimal transmission power and energy harvesting power in downlink and uplink scenarios. Numerical results show better performance of energy efficiency using optimal transmission power in a downlink scenario. Also, energy efficiency performance is improved using optimal energy harvesting power in the uplink scenario. The study can be extended for some future research like transmit antenna selection technique [29], two-slope path loss [21], truncated channel inversion power control [30], and secure CR network [31]. In addition, we calculate the energy efficiency of the whole network for the proposed scheme.

Availability of data and materials

Data used to support the findings of this study are already available in the manuscript.

Notes

MUE and BS are secondary nodes to utilize the unlicensed band.

To simple design, we assume one MUE. For the multiple active MUEs, BS is equipped with the massive multiple-input and multiple-output (M-MIMO) antenna. M-MIMO is one of the advanced technology of MIMO, having several antennas at BS to serve multiple active MUEs [28].

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial Intelligence

- BS:

-

Base station

- CR:

-

Cognitive radio

- DC:

-

Direct current

- EH:

-

Energy harvesting

- HPTSR:

-

Hybrid power time switching relaying

- IOT:

-

Internet of Things

- MAC:

-

Media access control

- MUE:

-

Mobile user equipment

- PU:

-

Primary users

- PSR:

-

Power splitting relay

- PT:

-

Primary transmitter

- RF:

-

Radio frequencies

- SU:

-

Secondary users

- WEH:

-

Wireless energy harvesting

References

M.N. Hindia, F. Qamar, H. Ojukwu, K. Dimyati, A.M. Al-Samman, I.S. Amiri, On platform to enable the cognitive radio over 5g networks. Wireless Pers. Commun. 113(2), 1241–1262 (2020)

H.M. Jawad, R. Nordin, S.K. Gharghan, A.M. Jawad, M. Ismail, Energy-efficient wireless sensor networks for precision agriculture: a review. Sensors 17(8), 1781 (2017)

G. Han, J.-K. Zhang, X. Mu, Joint optimization of energy harvesting and detection threshold for energy harvesting cognitive radio networks. IEEE Access 4, 7212–7222 (2016)

A.A. El-Saleh, T.M. Shami, R. Nordin, M.Y. Alias, I. Shayea, Multi-objective optimization of joint power and admission control in cognitive radio networks using enhanced swarm intelligence. Electronics 10(2), 189 (2021)

S. Ghosh, T. Acharya, S.P. Maity, Outage analysis in two-way communication with rf energy harvesting relay and co-channel interference. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 28(12), 3233 (2017)

H. Bello, Z. Xiaoping, R. Nordin, J. Xin, Advances and opportunities in passive wake-up radios with wireless energy harvesting for the internet of things applications. Sensors 19(14), 3078 (2019)

A. Andrawes, R. Nordin, M. Ismail, Wireless energy harvesting with cooperative relaying under the best relay selection scheme. Energies 12(5), 892 (2019)

A. Hooshiary, P. Azmi, N. Mokari, S. Maleki, Optimal channel selection for simultaneous RF energy harvesting and data transmission in cognitive radio networks. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 29(3), 3291 (2018)

S. Park, H. Kim, D. Hong, Cognitive radio networks with energy harvesting. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 12(3), 1386–1397 (2013)

A. Bhowmick, K. Yadav, S.D. Roy, S. Kundu, Throughput of an energy harvesting cognitive radio network based on prediction of primary user. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 66(9), 8119–8128 (2017)

H. Tran, T.X. Quach, H. Tran, E. Uhlemann, Optimal energy harvesting time and transmit power in cognitive radio network under joint constraints of primary users and eavesdroppers. In: Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Pers., Indoor Mobile Radio Commun.(PIMRC), pp. 1–8 (2017)

A. Obaid, X. Fernando, Wireless energy harvesting from ambient sources for cognitive networks in rural communities. In: 2017 IEEE Canada International Humanitarian Technology Conference (IHTC), pp. 139–143 (2017). IEEE

S.A. Islam, I.R. Sherif, M.A. Amr, Optimal sensing energy and sensing interval in cognitive radio networks with energy harvesting. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 34(7), 1–14 (2021)

E.-M.H.A. Abd, A.M. A, A.M. A, Evolutionary computation technique enhancing the performance of cognitive radio networks with energy harvesting. Ad Hoc Networks 107(102254), 1–15 (2020)

F.A. Tayel, I.R. Sherif, H.A.E.-M. Ahmed, M.A. Amr, Throughput maximization of hybrid access in multi-class cognitive radio networks with energy harvesting. IEEE Trans. Commun. 69(5), 2962–2974 (2021)

X. Liu, W. Lu, F. Li, M. Jia, X. Gu, Optimal simultaneous multislot spectrum sensing and energy harvesting in cognitive radio. In: 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), pp. 1–6 (2016).IEEE

P.N. Son, D. Har, N.I. Cho, H.Y. Kong, Optimal power allocation of relay sensor node capable of energy harvesting in cooperative cognitive radio network. Sensors 17(3), 648 (2017)

S. Lee, R. Zhang, K. Huang, Opportunistic wireless energy harvesting in cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 12(9), 4788–4799 (2013)

S. Sharma, D.S. Roy, S. Kundu, Physical layer security in bidirectional communication with swipt. Proc. Comput. Sci. 171, 1093–1101 (2020)

S. Ghosh, T. Acharya, S.P. Maity, On outage minimization in RF energy harvesting relay assisted bidirectional communication. Wirel. Netw. 25(7), 3867–3881 (2019)

S.R. Sabuj, M. Hamamura, Two-slope path-loss design of energy harvesting in random cognitive radio networks. Comput. Netw. 142, 128–141 (2018)

A. Prathima, S.D. Gurjar, A. Bhardwaj, Performance analysis and optimization of bidirectional overlay cognitive radio networks with hybrid-swipt. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 69(11), 13467–13481 (2020)

S. Xu, X. Song, L. Xia, Z. Xie, Energy efficiency maximization for energy harvesting bidirectional cooperative sensor networks with af modet. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 14(6), 2686–2708 (2020)

S.R. Sabuj, T.E. Nur, M. Hamamura, An energy-efficient model of random cognitive radio network: Rayleigh-lognormal environment. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 114, 1963–1981 (2020)

S.R. Sabuj, A. Ahmed, Y. Cho, K.-J. Lee, H.-S. Jo, Cognitive UAV-aided urllc and mmtc services: analyzing energy efficiency and latency. IEEE Access 9, 5011–5027 (2020)

S.R. Sabuj, R. Rayhana, A. Bobby, Spectral efficiency of energy harvesting random cognitive radio networks in dual-slope model. EAI Endorsed Trans. Cogn. Commun. 4(14) (2019)

R.M. Corless, G.H. Gonnet, D.E. Hare, D.J. Jeffrey, D.E. Knuth, On the Lambertw function. Adv. Comput. Math. 5(1), 329–359 (1996)

E. Björnson, J. Hoydis, L. Sanguinetti, Massive mimo networks: spectral, energy, and hardware efficiency. Found. Trends Signal Process. 11(3–4), 154–655 (2017)

S.R. Sabuj, M. Hamamura, Outage and energy-efficiency analysis of cognitive radio networks: a stochastic approach to transmit antenna selection. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 42, 444–469 (2017)

S.R. Sabuj, M. Hamamura, Uplink modeling of cognitive radio network using stochastic geometry. Perform. Eval. 117, 1–15 (2017)

S.R. Sabuj, M. Hamamura, Signal technique for friend or foe detection of intelligent malicious user in cognitive radio network. Int. J. Ad Hoc Ubiquitous Comput. 32(1), 29–42 (2019)

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledges the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Brac University, Bangladesh and Hanbat National University, South Korea for supporting the working together on this research work. \(\ldots\)

Funding

This work was supported by the research grant Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) under Grant FRGS/1/2020/ICT03/UKM/02/6 and GGPM-2020-028.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Md. Monwar Jahan Chowdhury and Saifur Rahman Sabuj; Formal analysis: Md. Monwar Jahan Chowdhury; Funding acquisition: Mohammad Kamrul Hasan; Investigation: Shakil Ahmed and Saifur Rahman Sabuj; Methodology: Md. Monwar Jahan Chowdhury; Project administration: Mohammad Kamrul Hasan; Resources and Software: Shakil Ahmed and Saifur Rahman Sabuj; Supervision: Mohammad Kamrul Hasan and Saifur Rahman Sabuj; Writing original draft: Md. Monwar Jahan Chowdhury; Writing review & editing: Mohammad Kamrul Hasan, Shakil Ahmed, Jamel Nibhen, Khairul Azmi Abu Bakar. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Mohammad Kamrul Hasan is currently working as a Senior Lecturer in the Network and Communication Technology research cluster, Center for Cyber Security, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM). He completed a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree in Electrical and Communication Engineering from the faculty of Engineering, International Islamic University, Malaysia, in 2016. Dr. Hasan completed his M.Sc. degree in Communication Engineering from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, International Islamic University, Malaysia, in 2012. Dr. Hasan is a Senior Member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers since 2013, a Member of the Institution of Engineering and Technology, and a member of the Internet Society. He has served the IEEE IIUM student branch as chair from 2014 to 2016. He is a certied professional technologist and consulting the related industries. His research interest includes telecommunications, Internet of Things, Vehicular networks, Smart grid Technologies, microprocessor and Interfacing, and cyber-physical Security.

Md Monwar Jahan Chowdhury completed his B.Sc degree in Electronics and Communication Engineering from Brac University, Bangladesh. His area of interest and research includes wireless sensor networks, Internet of things, wireless communication, cognitive radio network, block chain, etc. He has presented his paper in conferences and journals both home and abroad. He is currently serving in a telecommunication firm under the RF measurement and EMF testing division. His current research work includes investing the bidirectional communication in cognitive radio network and Blockchain technology.

Shakil Ahmed obtained his BS degree in Electrical and Electronic Engineering from Khulna University of Engineering and Technology (KUET), Bangladesh, in 2014. He received his MS degree in Electrical Engineering from Utah State University, Logan, Utah, the USA, in 2019. Currently, he is pursuing his Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering at Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, USA. He is a student member of IEEE. He received the prestigious Presidential Doctoral Research Fellowship from the school of graduate studies at Utah State University. His current research interests include next-generation wireless communications, wireless network design and optimization, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), physical layer security, and mmWave channel characterization.

Saifur Rahman Sabuj is currently working with Electronic Engineering Department as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Hanbat National University, South Korea. He has been in the position of an Assistant Professor in the department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Brac University, Bangladesh, since September 2017. From 2008 to 2013, he was a faculty member of Green University of Bangladesh, Metropolitan University, Sylhet and Bangladesh University. He received a B. Sc in Electrical, Electronic and Communication Engineering from Dhaka University, Bangladesh in 2007, an M. Sc Engineering in the Institute of Information and Communication Technology, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Bangladesh in 2011, and a Ph.D. degree in the Graduate School of Engineering, Kochi University of Technology, Japan in 2017. His research interests include MIMO-OFDM/NOMA, Cooperative Communication, Cognitive Radio, Internet-of-things, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Machine-to-machine for wireless communications.

Jamel Nebhen received the M.Sc. in Microelectronics from the National Engineering School of Sfax, Tunisia in 2007, and the Ph.D. degrees from the Aix-Marseille University, France, in 2012, all in Microelectronics. From 2012 to 2018, he worked as a Postdoctoral Researcher in France in LIRMM-Lab Montpellier, IM2NP-Lab Marseille, ISEP Paris, LE2I-Lab Dijon, Lab-Sticc Telecom Bretagne Brest, and IEMN-Lab Lille. Since 2019, he joined the Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia, as an Assistant Professor. His research interests are mainly in the design of analog and RF integrated circuits, IoT, biomedical circuit, and sensors instrumentation.

Khairul Azmi Abu Bakar received the degree in Computer Engineering from Iowa State University, USA and master degree in Communication and Computer from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. He was awarded Ph.D. degree in Electrical Engineering from University of Strathclyde, United Kingdom for the study on free-riding nodes in an open MANET. He is currently a senior lecturer at Center for Cyber Security under Faculty of Information Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Prior to that, he was a staff researcher at MIMOS Berhad which is a Malaysia’s national applied research and development center in microelectronic and ICT. He has been involved in many R&D projects in the field of micro-controller, smartcard, security systems under open source platform. His primary research interests include network security, internet of things and computer network. He is also a IEEE member.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors have agree and given their consent for submission of this paper to Euraship Journal of Wireless Communications.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hasan, M.K., Chowdhury, M.M.J., Ahmed, S. et al. Optimum energy harvesting model for bidirectional cognitive radio networks. J Wireless Com Network 2021, 199 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13638-021-02064-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13638-021-02064-5