Abstract

Background

On-farm hatching (OH) systems are becoming more common in broiler production. Hatching conditions differ from conventional farms as OH chicks avoid exposure to handling, transport, post-hatch water and feed deprivation. In contrast, chicks in conventional hatching conditions (CH) are exposed to standard hatchery procedures and transported post hatching. The objectives of this pilot study were to investigate the prevalence and frequency of Escherichia coli resistant to antimicrobials, including presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli, isolated from environmental and faecal samples from OH versus CH hatching systems, and to investigate the presence of ESBL/AmpC-producing encoding genes.

Results

Environmental samples were collected from one flock in 10 poultry farms (5 OH farms, 5 CH farms) on day 0 post disinfection of the facilities to assess hygiene standards. On D10 and D21 post egg/chick arrival onto the farm, samples of faeces, boot swabs and water drinker lines were collected.

E. coli were isolated on MacConkey agar (MC) and MacConkey supplemented with cefotaxime (MC+). Few E. coli were detected on D0. However, on D10 and D21 E. coli isolates were recovered from faeces and boot swabs. Water samples had minimal contamination. In this study, 100% of cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates (n=33) detected on selective media and 44% of E. coli isolates (84/192) detected on nonselective media were multidrug resistant (MDR). The antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genotype for the 15 ESBL/AmpC producing isolates was determined using multiplex PCR. Six of these were selected for Sanger sequencing of which two were positive for blaCMY-2, two for blaTEM-1 and two were positive for both genes.

Conclusions

There was no difference in E. coli isolation rates or prevalence of AMR found between the OH versus CH systems, suggesting that the OH system may not be an additional risk of resistant E. coli dissemination to broilers compared to the CH systems. The frequency of β-lactam resistant E. coli in boot swab and faeces samples across both OH (24/33 (73%)) and CH (9/33 (27%)) systems may indicate that hatcheries could be a reservoir and major contributor to the transmission of AMR bacteria to flocks after entry to the rearing farms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is now recognised as one of the world’s most important health challenges [37]. Antimicrobial use (AMU) in agriculture and human and veterinary medicine is associated with an increase in AMR globally [33] and the misuse of antimicrobials in agriculture contributes to AMR to antimicrobials that are frequently used in human medicine [36]. The introduction of extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESC) to human and veterinary medicine has improved the treatment of infection. However, resistance caused by extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and AmpC β-lactamase produced by E. coli and associated resistance to extended spectrum cephalosporins in poultry meat is a concern for public health [30].

Many studies have shown that the gastrointestinal tract of healthy broiler chickens can be a reservoir for antimicrobial resistant bacteria, particularly ESBL/AmpC-producing-E. coli [17, 32], with faeces, water, and litter acting as potential transmission sources [21]. Breeder flocks may be the original source of contamination, as one day old chicks are known to be a major risk factor for introduction of ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli [11, 28] However, various important sources within the broiler production chain can contribute to the transfer of resistant bacteria to the birds on farm [20]. Transfer may begin at broiler grandparent/parent level, it may be from hatcheries or from residual contamination from the broiler rearing farms themselves [20, 23, 28]. Many factors are likely to influence the prevalence of resistant organisms within broiler production, such as: AMU, climate control, flock origin, hatchery, hygiene, nutrition, disease outbreaks/control, removal of waste (litter, devices, dead birds etc.), pest control and disinfection [15].

In the conventional hatching system (CH), chicks are hatched at the hatchery, vaccinated, and transported to the rearing farms before they can access any essential water or food; this period may last up to 48 hours. In the on-farm hatchery (OH) system, in contrast, eggs are transported to the rearing farm thus allowing the chicks immediate access to water and food directly after hatching. Aside from this, chicks that are born in hatcheries are exposed to environmental challenges and stressors such as dust, disinfection, and pathogen loads [9], as well as high noise level and continuous darkness [3], all of which are either reduced greatly or eliminated in an OH system. Such early life stressors can have long term consequences on the development and survival of chicks in later life [10]. In The Netherlands, a study reported improved health, welfare, and performance of chicks in the first week of life when reared in an OH system [9]. Another study investigated physiological differences in broiler chicks from hatching to day 45 in two different hatching systems: the ‘Patio’ system (hatching and brooding are combined) vs CH and concluded that either system had minor effects on hatching physiology [34]. Neither of these studies investigated AMR.

To date, published data relating to AMR associated with OH flocks in broiler houses and CH flocks in a hatchery are not available and therefore, the objective of this pilot study was to investigate the prevalence of antimicrobial resistant E. coli and AMR genes encoding clinically important β-lactamases, specifically ESBL/AmpC, in OH and CH broiler chickens and their rearing environment.

Materials and methods

Study Design

The study took place between October and December 2019. Ten broiler farms contracted by the same company, located in the same geographical region in the Republic of Ireland and served by the same hatchery participated in the study. The study batch on each farm consisted of one production round whereby five farms operated the conventional hatching system (CH farms) and five farms operated the on-farm hatching system (OH farms).

In the OH farms, pre-incubated eggs were transported from the hatchery to the broiler farms in setter trays and placed over a two-meter-wide strip directly onto a clean litter bed in the broiler rearing house by a self-propelled egg placing machine (Nestborn, Tienen, Belgium) approximately 3 days pre-hatching. The machine had two manual operators and a capacity to place 60,000 eggs per hour. The OH system completely removes the need for a hatchery service and eliminates the transport of live chicks. The CH farms used a standard method, whereby live chicks were transported directly to the rearing house on the farm after hatching in a hatchery. During the rearing period involved in this study, the birds did not receive antimicrobial treatment on any of the participating farms; vaccinations were administered as per the veterinary plan of the poultry company.

Sampling

Before chicks or eggs arrived at the farm (D0) environmental samples were taken from the rearing house to study baseline AMR in the E. coli isolates. On each farm, five individual samples from the floor, wall, vent, feeders, and drinkers were collected using sponge swabs (3M Health Care, Minneapolis, USA). The floor sample was collected by swabbing three areas of 1 m2 at the front, middle and end of the rearing house. Similarly, an area of 1 m2 was swabbed on the wall. One vent on the inside wall of the house was also swabbed at the front, middle and end of the rearing house as well as 5 clean feeders along a feeder line and 5 clean drinkers along a drinker line. Additionally, one clean litter sample, a feed sample (10 g) from one silo, pooled water sample (600 ml) from the water source and pooled water sample (600 ml) from the drinker end line were also collected. On OH farms, 5 swabs from external and internal areas of the egg placing machine were collected. Samples were stored in sterile containers and transported to the laboratory in cool boxes and processed on the same day of collection. Feed and clean litter samples were pooled by hatching method (i.e., OH and CH) for testing, because few E. coli were isolated from these samples in a pre-trial test run.

On day 10 (D10) and day 21 (D21) post egg/chick arrival, 20 g of freshly dropped faeces were taken from five distinct areas in each rearing house. D10 and D21 are the two main stages of feed change in the broiler rearing period and therefore were selected as sampling days. One pair of boot swab samples per house was also collected; a researcher walked from one end of the house and back again wearing pre sterilised boot swabs. The swabs were then stored back in the original packaging for microbiological examination. On D10 and D21, water sampling was repeated as per D0 procedure.

Microbiological Analysis

Bacterial Isolation

Samples were stored at 4 °C during transport and on arrival at the laboratory. The sponge swab (5 pooled sponges), boot swab (one pair), faeces (20 g) (pooled/farm) and feed (10 g) samples were mixed with 300 ml, 180 ml, 180 ml, and 90 ml respectively of buffer peptone water (BPW) to make a 1:10 suspension and were homogenised using a stomacher (stomacher 400 circulator; Seward Limited, West Sussex, UK) for two minutes at 200 rpm. The homogenate from each sample was streaked onto one supplemented MacConkey agar (MC) plate and spread plated onto one supplemented (i.e., supplemented with 1mg/l cefotaxime MacConkey agar (MC+)) plate [2].

On day 0, water samples were collected in 500ml sterile containers from the source and drinker lines on each farm. The samples were transported from the farm in a cooler box and refrigerated at 4 °C on arrival to the lab on the same day. The desired volume of water was measured and then filtered aseptically using a vacuum pump through sterile, cellulose nitrate membrane filters, 47mm diameter and pore size 0.45μm. A total of 100 ml of each water sample was filtered through three separate sterile filters. Using a sterile forceps, a single filter with the grid side up was placed on two non-supplemented and one supplemented MacConkey agar plate. A newly sterilised water funnel was used to filter each water sample from each farm. A filter sterility check was performed by placing one membrane filter on a MacConkey plate and incubating it at 35°C ± 0.5°C for 24 ± 2 hours; absence of growth indicated sterility of the batch of filters.

All samples on MacConkey agar plates were incubated at 37 °C for 22 hours. Up to five suspect colonies with typical E. coli morphology from each of the MC and MC+ agars were transferred onto Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide (TBX) agar and TBX supplemented with cefotaxime (TBX+) and incubated at 37°C for 22 hours; E. coli isolates appear as blue colonies on TBX. Isolates that did not present typical E. coli morphology on TBX were further tested for production of indole and failure to utilise citrate. Selected isolates were sub-cultured on sheep blood agar to ensure purity before they were preserved onto cryo-beads (TSC Technical Service Consultants, UK) at -70 °C for future antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

The BioMérieux VITEK2 system was used to test antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolates using the AST GN98 card. Isolates were resuscitated onto sheep blood agar from frozen and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. A panel of 17 antibiotics was tested: ampicillin (AMP), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC), cefalexin (CEF), cefpodoxime (CPD), cefovecin (CEV), ceftazidime (CTZ), ceftiofur (CFR), imipenem (IMP), amikacin (AMK), gentamicin (GEN), ciprofloxacin (CIP), enrofloxacin (ENR), marbofloxacin (MAR), doxycycline (DOX), nitrofurantoin (NIT), chloramphenicol (CHL) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used for quality control.

Results were interpreted according to the criteria used by the VITEK software as shown in Table 1. Vitek criteria are based on those of CLSI [5, 6].

VITEK2 software reports presumptive ESBL. Isolates displaying resistance to three or more antimicrobial classes were considered MDR [22]. The resistance status of each isolate was recorded as a binary variable, either susceptible (S) or resistant (R). Isolates with an intermediate (I) status were considered resistant (R).

Investigation of β-Lactamase Encoding Genes using Multiplex PCR Technique

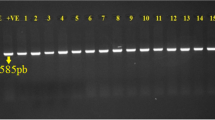

Presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli were tested for β-lactamase-encoding genes using the multiplex PCR methods described by [7]. Rapid DNA extraction was performed on these isolates by the boiling method [7]. Each isolate was tested for: β-lactamase encoding genes (TEM (800bp), OXA (564bp), and SHV (713bp)) (Multiplex I); ESBL (CTX-M Groups 1 (688bp), 2 (404bp) and 9 (561bp), 8/25 (326bp) (Multiplex II); plasmid mediated AmpC (ACC (346bp), FOX (162bp), MOX (895bp), CIT (538bp), DHA (997bp) and EBC (683bp)) (Multiplex III); and VEB (648bp), PER (520bp), GES (399bp) (Multiplex IV). Positive control strains were obtained from Galway University Hospital National Microbiology Reference Library.

Each multiplex PCR reaction (I, II, III and IV) was carried out as per Dallenne et al. [7]. Briefly, PCR reactions [final volume: 25 μl (23.5μl master mix (MM) & template DNA (1.5 μl))] were set up with (2X QIAGEN multiplex MM, template DNA, RNase-free water, and primers). Primers were suspended to the appropriate concentration (Multiplex I: 0.4 pmol /10 μl, Multiplex II: 0.2 pmol /10 μl, Multiplex III: 0.2 pmol /20 μl and Multiplex IV: 0.3 pmol /10 μl,). For amplification, thermocycling was programmed in the following steps: template denaturation for 15 mins at 95 °C (1 cycle), 30 sec at 94 °C (30 cycles), annealing 90 sec at 60 °C (30 cycles), 90 sec at 72 °C (30 cycles) and final elongation 10 mins at 72 °C (1 cycle).

Gel electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 2.5 hours, using a 2 % agarose gel and SYBR SAFE DNA gel stain. To visualise the DNA bands a UV transilluminator (Model: SYNGENE G: BOX) was used. Selected PCR products successfully amplified were sequenced using the Sanger sequencing method to determine the targeted β-Lactamase gene(s). Sanger sequencing is required to fully identify the specific β-lactamase gene targeted as the TEM primers target TEM variants including TEM-1 and TEM-2 (see [7], Multiplex I), and the CIT primers target LAT-1 to LAT-3, BIL-1, CMY-2 to CMY-7, CMY-12 to CMY-18 and CMY-21 to CMY-23, (see [7], Multiplex III). Sequence analysis was performed using Reverse Compliment (https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms/rev_comp.html) and nucleotide BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn). Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) (https://card.mcmaster.ca) was used to compare the nucleotide sequence queries with known β-Lactamase gene sequences by multiple sequence alignment.

Statistical analysis

The percentage resistance of E. coli isolates to each antimicrobial was calculated in Excel. Differences between samples from OH and CH broiler operating system were analysed using the Mann Whitney U test using SAS 9.4 (The SAS Institute, Carey, NC). Alpha level for determination of significance was 0.05.

Results

Total number of isolates recovered from non-selective (MC) and selective (MC+) media by hatching system, sample type and sample day (D) are shown in Table 2. No E. coli were recovered from the faecal samples collected from one OH farm on D21 when plated on MC or MC+ media despite the fact E. coli isolates were detected on the same farm in faeces sampled on D10 (Table 2).

On D0, few E. coli isolates were detected in environmental samples which included feed from the silo, clean litter, sponge swabs, water from the source and the drinker lines. All samples were negative on both MC and MC+ media for both hatching systems with the following exceptions from MC media: one CEF resistant isolate from a sponge swab sample from one OH farm, one CEF resistant isolate from a water (source) sample from one CH farm and one resistant isolate (AMP, AMC, CEF, DOX, SXT) from a clean litter sample from the same CH farm. On another OH farm, a single E. coli isolate with CEF, CIP, ENR, MAR, DOX, CHL resistance was detected by sponge swab sampling of the egg placing machine.

Presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli were isolated on two farms. Presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli isolates were detected in faecal and boot swab samples on MC+ media from one OH farm at D10 but were only detected in boot swab samples from the same farm at D21 (Table 2). E. coli were isolated on MC+ media from faecal and boot swab samples collected on one CH farm on D21 in contrast to D10 when it was not detected (Table 2). The same two farms of the five OH farms investigated were positive on MC+ media for presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli isolates on both D10 and D21. Presumptive ESBL/AmpC E. coli producing isolates on MC+ media were recovered from boot swab (n=4) and faeces (n=5) on a single CH farm on D21 (Table 2).

The percentage of E. coli recovered on MC media from boot and faecal swabs collected on farms with OH and CH rearing systems, that were resistant to selected antimicrobials on D10 and D21 are presented in Fig. 1. Resistance to cefpodoxime, ceftazidime, ceftiofur, imipenem and amikacin was not detected in any isolate recovered from non-selective plates. There were no significant differences (Mann Whitney U test) between the two hatching systems in resistance to any of the antimicrobials tested. Resistance to cefalexin was high in E. coli isolated from all sample types and days, followed by resistance to ampicillin, trimethoprim, doxycycline and chloramphenicol.

Heat map displaying the resistance percentage of E. coli isolates recovered on (MC) media according to sample type and rearing stage. Samples were collected from five farms with conventional hatching (CH) and five farms with on-farm hatching (OH), both with low antimicrobial use. a(OH = on-farm hatching; CH = conventional hatching). Resistance to imipenem, amikacin, ceftazidime, cefpodoxime or ceftiofur was not detected in any isolate

Resistance in E. coli recovered from selective media on D10 and D21 is presented in Fig. 2. Presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli were detected on both D10 and D21 in samples from two OH farms and in addition they showed high levels of resistance to tetracycline, fluoroquinolones and potentiated sulphonamides. One CH farm had cefotaxime-resistant E. coli present at D21 in boot swab and faeces samples but did not have any cefotaxime-resistant E. coli present in samples collected on D10. The highest resistance percentage was seen in boot swab samples from OH farms at D10.

Heat map displaying resistance percentage of E. coli isolates recovered from faeces and boot swab samples on MC+ media from one farm with conventional hatching (CH) and two farms with on-farm hatching (OH) with low antimicrobial use. Resistance to amikacin or imipenem was not detected in any isolate. Amox/clav - amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; Trim/sulfa - trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

Resistance to imipenem and amikacin was not found on any farm at any sampling point. In this study, 84 out of 192 (44%) isolates recovered from MC media were MDR and all of the 33 ESBL/AmpC-producing isolates recovered from the MC+ plates were MDR.

The number and percentage of AMR E. coli isolates with specific resistance patterns that were detected on MC media on D10 and D21 from boot swab and faeces samples are shown in Table 3.

Numbers and percentage of AMR E. coli isolates with specific resistance patterns that were detected on selective MC+ media on sampling periods D10 and D21 from boot swab and faeces sample types are presented in Table 4. All the 33 isolates recovered were MDR.

Investigation of β-lactamase-encoding genes

Fifteen presumptive isolates from the farm with the most positive samples were selected for testing using multiplex PCR. The PCR multiplex results and AST profile for all 15 isolates are illustrated in Fig. 3. On D10, seven out of 10 isolates were positive in multiplex I and all but one was positive in multiplex III. No isolate was positive in multiplex II or IV while one isolate was negative in all four multiplexes. In contrast, all five isolates from D21 were positive in multiplex I only. In the D10 samples, only the isolate negative in all multiplexes was susceptible to fluoroquinolone whereas all isolates from D21 were susceptible. Two of the isolates that were positive in each multiplex and two of the isolates that were positive in both multiplex I and multiplex III were submitted for Sanger sequencing (six in total). The gene detected in multiplex I was identified by sequencing as blaTEM-1 (GenBank Accession no: 30003984) for all four positive isolates and the gene detected in multiplex III was blaCMY-2 (GenBank Accession no: 3003138) for all four positive isolates.

Heat map displaying antimicrobial resistance susceptibility patterns of presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli recovered on selective media (MC+) according to sample day (D10 and D21) and type (boot swab and faeces). Selected presumptive ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli isolates were tested for β-lactamase-encoding genes using the multiplex PCR method. Multiplex I targeted TEM, SHV and OXA-1-like β-lactamases, multiplex II targeted CTX-M group 1, 2, 9 and 8/25 β-lactamases, multiplex III targeted plasmid mediated AmpC β-lactamases and multiplex IV targeted VEB, PER and GES β-lactamases. Six of the E. coli isolates with a PCR product amplification were subsequently sent for Sanger sequencing to fully identify the specific β-lactamase gene targeted: blaTEM-1 was detected in all multiplex I positive samples; blaCMY-2 in all multiplex III positive samples. Each column represents the data of a single isolate

Discussion

The detection of antimicrobial resistant E. coli in the environment and the microbiome of broiler chickens is becoming more common and a cause for concern [31]. Such detection shines a light on the importance of routine investigation of commensal bacteria in broiler production in Ireland and elsewhere. The ‘One Health’ concept recognises that the health of humans, animals and the environment is interlinked with potential crossover of AMR reservoirs, especially E. coli, between different settings [25]. In Ireland, levels of antimicrobial resistant E. coli isolated from broilers are declining; this gradual trend may be reflective of restricted AMU practice in recent years. As per the [13] report, a decline in the occurrence of resistance to AMP, CIP and TET in E. coli isolated from broilers has been detected. Nevertheless, high levels of resistance to these antimicrobials were found in this study. In the most recent report based on 2019 data submitted from Ireland, levels of resistance of 35.9%, 5.3% and 57.1% to AMP, CIP and TET respectively were recorded in poultry, with MDR E. coli at 38.2% [13]. A total of 84/192 (44%) of E. coli isolates from MC plates in this study were MDR, which is higher than the EFSA figure. However, findings from this report [13] are based on data collected from broilers at slaughter in a nationwide study and using harmonised ECOFFs whereas, the findings in this study represent ten farms and use clinical breakpoints as set by the VITEK2. Therefore, direct comparison of findings is not possible.

Resistant strains of E. coli may persist in farm environments and rapidly colonise new flocks [11, 20]. Recent studies have described various modes of transmission of antimicrobial resistant E. coli from the hatchery environment and along the entire broiler rearing process [12, 29]. However, although some studies examining production and other data in chickens reared in OH or CH intensive broiler rearing systems have been published, none have compared antimicrobial resistance in E. coli recovered from these systems. Of the ten farms studied, E. coli was consistently detected on both CH an OH farms on D10 and D21. We hypothesised that levels of antimicrobial resistance in E. coli in the OH system would be lower than in the CH systems because of the elimination of hatching on other premises and avoidance of transportation, thus reducing possible exposure of chicks to sources of antimicrobial resistant organisms and stress. Under the conditions of this study, no differences were observed in recovery of resistant E. coli between OH and CH farms. Nevertheless, high levels of MDR E. coli isolates were recovered on D10 and D21 on both farm types. The isolation rates of E. coli on OH farms from this study may raise concerns about the introduction of antimicrobial resistant E. coli to chicks via the grandparent/parent lines or in the eggs, in the steps before the hatching period on the rearing farms. For example, a study in 2008 reported that the risk of introducing ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli to the flock was associated with purchasing chicks that were already positive due to clonal spread in grandparents and parent flocks [23]. Persistence of AMR on farms and transmission and movement of antimicrobial resistant organisms may occur through national or international importation of breeding stock to hatcheries. Furthermore, the repeated introduction of antimicrobial resistant organisms to young chicks from persistence within the hatchery and movement between premises via stock, transport vehicles, personnel, or wind is also possible [8]. In addition, the detection of E. coli, including cefotaxime resistant isolates, on OH farms may suggest transmission of antimicrobial resistant E. coli from eggshell contamination in the hatchery before or after shell disinfection. This theory is supported by [28] who concluded that egg-shell surfaces can continue to serve as a source of contamination even after disinfection. However, Hiroi et al. [19] and Laube et al. [20] suggested that environmental contamination of houses and insufficient disinfection were the cause of high levels of antimicrobial resistant E. coli in broiler faeces. In the study reported here, on D0, only four isolates of E. coli were recovered in environmental samples on two of the ten farms tested, suggesting that on-farm cleaning and disinfection between batches was highly effective. However, on D0, one MDR E. coli isolate was detected on the egg placing machine while it was in use; this suggests contamination between houses or farms due to insufficient disinfection could occur as the machine was used on multiple farms each day.

On D10, E. coli isolates were recovered from water drinker lines on four farms and from five farms on D21, two of which were the same as on D10 (Table. 2). This finding suggests that a build-up of E. coli occurred in water lines over time, possibly associated with biofilm formation.

On many farms the contamination increased over time. Minimal evidence of faecal contamination was found at D0 (4 isolates) but a high proportion of MDR E. coli was found in samples collected on D10 and D21. Farms selected for participation in this study were already designated by the company for inclusion in OH or CH systems. All flocks were sampled concurrently and because all farms were contracted to the same company, management and operating systems were similar across all farms including feed to minimise confounding factors as much as possible during the study. Results obtained from this study show a high occurrence of antimicrobial resistant E. coli in broiler flocks from both rearing pathways.

Of the 33 ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli isolates detected from MC+ media from boot swab and faeces samples all were MDR. On MC media 84 isolates (44%) were MDR, which highlights the presence of MDR E. coli in the microbiome and environment of the broilers. ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli were not detected on the MC medium which shows that they were not abundant. The epidemiology of ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli is complex and the result of this study enhances the knowledge of AMR in broiler flocks by evaluating the AMR patterns of E. coli and provides additional information to the data already available in different European countries [13]. Fluoroquinolone resistance was common in MDR isolates from broilers in this study as 18 of 33 (55%) of E. coli recovered on MC+ media were fluoroquinolone resistant. The frequent use of fluoroquinolones over many years may explain the high levels of resistance detected. In addition, high fluoroquinolone resistance detected in presumptive ESBL/AmpC isolates suggests co-resistance, with genes encoding fluoroquinolone resistance possibly being on the same mobile genetic element as the cefotaxime resistance encoding genes. An alternative explanation would be the presence of a chromosomal mutation in these isolates. The rapid spread of antimicrobial resistant E. coli that harbour mobile genetic elements encoding AMR, raises an ongoing and immediate issue due to the hypothesised transmission to humans by way of the food chain.

Results from this study were based on multiple isolates from pooled samples, this approach was considered acceptable to ensure an unbiased estimate of E. coli resistance prevalence. Cefotaxime is recommended for routine monitoring as it is proven to be an effective substrate for inclusion in media for detection of the common ESBLs including the CTX-M enzymes [12]. The study was limited as only a small number of farms were used to detect differences in OH and CH hatching systems, but data collected within this small study will be useful for future research.

There are frequent reports from countries across the EU presenting information on the dissemination of ESBL-producing E. coli in poultry [14]. β-lactamase encoding genes have been reported in E. coli isolated from Irish food producing animals [35, 38]. In this study, investigation into the presence of β-lactamase encoding genes and plasmid-encoded AmpC genes in cefotaxime resistant E. coli isolates was performed on one of the farms. On this farm, all but one of the isolates recovered on D10 were positive in multiplex III (blaCMY-2 positive in those that were submitted for Sanger sequencing), however, by D21 all isolates were negative in multiplex III. This suggests the two different cephalosporin resistant E. coli populations detected may be age dependant which could reflect different sources of transmission, for example, hatchery versus farm. Since this study was limited to just one flock on this farm and the genetic basis for cephalosporin resistance on the other farms was not determined, further investigation is required. The Sanger sequencing results suggest that positive multiplex I isolates carry the blaTEM-1 gene which does not explain cephalosporin resistance in the D21 isolates. The most likely explanation is chromosomal AmpC production which is a relatively common mechanism in some countries [26].

In poultry, CMY-2 is the most common plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase in E. coli isolates of animal and human origin [18]. The prevalence of CMY-2-mediated cephalosporin resistant E. coli can differ depending on geographical region [16]. In E. coli isolates of animal origin, CMY-2 was the most frequently detected cephalosporin resistance determinant in Denmark (83%) and imported broiler meat (42%) until 2013 [1]. In 2014, a reduction in the occurrence of CMY-2 producing E. coli was detected in Danish (23%) and imported (33%) broiler meat, this change most likely comes from the discontinued use of 3rd generation cephalosporins in hatcheries at the top of the broiler production pyramid [4]. The high prevalence of the blaCMY-2 gene in isolates from poultry is an important public health concern. Our results show, the blaCMY-2 positive isolates were MDR, including fluoroquinolone resistant. These findings are comparable to those of a study by [27]. Agersø [1] reported that, ESBL genes and ESBL producing E. coli clones carrying plasmids were detected in imported broiler parent flocks on a Danish conventional broiler farm, even though cephalosporins had never been used. Furthermore, in a Norwegian study, stable colonisation with blaCMY-2 producing E. coli was observed through an entire broiler production chain from grandparent birds to retail meat [24].

Conclusion

Broiler chickens may be a reservoir for antimicrobial resistant E. coli from early life and thus, may facilitate transmission of antimicrobial resistant E. coli to other chickens in the same flock. Very few antimicrobial resistant E. coli isolates were detected on D0, but a greater number of samples were positive on D10 and D21 of the broiler rearing period, although antimicrobials were not administered to the birds at any time. Contrary to the initial theory on the benefits of the OH broiler rearing system, it did not appear to have reduced the prevalence of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in the flocks. As most of the antimicrobial resistant E. coli isolates were detected on D10 and D21 post arrival of eggs/chicks and not on D0, this may indicate transmission to the birds from the hatchery environment rather than from the rearing farms. Further investigation of this finding using a larger sample size would be useful.

The high prevalence of MDR E. coli is of concern in terms of resistance to critically important antibiotics and human health. Analysing phenotypic AMR of commensal E. coli from the environment and intestinal flora of broiler chickens can provide information on the reservoirs of AMR bacteria that may be disseminated between animal and human populations.

Results from this study suggest that important mitigation strategies should include more stringent biosecurity and disinfection measures in the hatchery and on farms, to prevent buying in broilers carrying resistance at the beginning of life and testing of imported breeding stock for antimicrobial resistant E. coli before entry to the breeding farms. Education of farmers and farm workers on the harmful impacts of AMR would also be of benefit.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

Antimicrobial

- AMP:

-

ampicillin

- AM:

-

amoxycillin clavulanic acid

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial Resistance

- AMU:

-

Antimicrobial Use

- AMURAP:

-

Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Animal Production

- AST:

-

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- BPW:

-

Buffer Peptone Water

- BS:

-

Boot Swab

- CARD:

-

Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database

- CEF:

-

cefalexin

- CEV:

-

cefovecin

- CFR:

-

ceftiofur

- CH:

-

Conventional-Farm Hatching

- CHL:

-

chloramphenicol

- CIP:

-

ciprofloxacin

- CPD:

-

cefpodoxime

- CLSI:

-

Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute

- CTZ:

-

ceftazidime

- DAFM:

-

Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- EFSA:

-

European Food Safety Authority

- ESBL:

-

Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamases

- ESC:

-

Extended Spectrum Cephalosporin

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- GN:

-

Gram Negative

- MIC:

-

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- MC:

-

MacConkey Agar

- MC+:

-

MacConkey Agar plus cefotaxime 1 mg/L

- MDR:

-

Multi Drug Resistant

- NCBI:

-

The National Centre for Biotechnology

- OH:

-

On-Farm Hatching

- SOP:

-

Standard Operating Procedure

- SXT:

-

trimethoprim sulphonamide

- TBX:

-

Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide agar

References

Agersø Y, Jensen JD, Hasman H, Pedersen K. Spread of Extended Spectrum Cephalosporinase-Producing Escherichia coli Clones and Plasmids from Parent Animals to Broilers and to Broiler Meat in a Production Without Use of Cephalosporins. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2014;11(9). https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2014.1742.

Anjum MF, Zankari E, Hasman H. Molecular Methods for Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance. Microbiol Spectrum. 2017;5(6). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0011-2017.

Archer GS, Mench JA. The effects of the duration and onset of light stimulation during incubation on the behavior, plasma melatonin levels, and productivity of broiler chickens1. J Anim Sci. 2014;92(4):1753–8. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2013-7129.

Baron S, Jouy E, Larvor E, Eono F, Bougeard S, Kempf I. Impact of Third-Generation-Cephalosporin Administration in Hatcheries on Fecal Escherichia coli Antimicrobial Resistance in Broilers and Layers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(9). https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03106-14.

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility test for Bacteria Isolated From Animals; 3rd VET01-S3. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 27th Informational Supplement. M100-S27. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017.

Dallenne C, da Costa A, Decré D, Favier C, Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(3):490–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkp498.

Davies R, Wales A. Antimicrobial Resistance on Farms: A Review Including Biosecurity and the Potential Role of Disinfectants in Resistance Selection. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Safety. 2019;18(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12438.

de Jong IC, Gunnink H, van Hattum T, van Riel JW, Raaijmakers MMP, Zoet ES, et al. Comparison of performance, health and welfare aspects between commercially housed hatchery-hatched and on-farm hatched broiler flocks. Animal. 2019;13(06):1269–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731118002872.

Decuypere E, Tona K, Bruggeman V, Bamelis F. The day-old chick: a crucial hinge between breeders and broilers. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2001;57(2):127–38. https://doi.org/10.1079/WPS20010010.

Dierikx CM, van der Goot JA, Smith HE, Kant A, Mevius DJ. Presence of ESBL/AmpC -producing Escherichia coli in the broiler production pyramid: A descriptive study. PLoS One. 2013;8(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079005.

EFSA. Report from the Task Force on Zoonoses Data Collection including guidance for harmonized monitoring and reporting of antimicrobial resistance in commensal Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. from food animals. EFSA J. 2008;6(4). https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2008.141r.

EFSA, & ECDC. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2018/2019. EFSA J. 2021a;19(4). https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6490.

EFSA, & ECDC. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2018/2019. EFSA J. 2021b;19(4). https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6490.

European Food Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion on the public health hazards to be covered by inspection of meat (poultry). EFSA J. 2012;10(6) https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2741.

Ewers C, Bethe A, Semmler T, Guenther S, Wieler LH. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from livestock and companion animals, and their putative impact on public health: a global perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(7). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03850.x.

Gazal LE, Medeiros LP, Dibo M, Nishio EK, Koga VL, Gonçalves BC, et al. Detection of ESBL/AmpC-Producing and Fosfomycin-Resistant Escherichia coli From Different Sources in Poultry Production in Southern Brazil. Front Microbiol. 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.604544.

Hansen KH, Bortolaia V, Nielsen CA, Nielsen JB, Schønning K, Agersø Y, et al. Host-Specific Patterns of Genetic Diversity among IncI1-Iγ and IncK Plasmids Encoding CMY-2 β-Lactamase in Escherichia coli Isolates from Humans, Poultry Meat, Poultry, and Dogs in Denmark. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(15). https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00495-16.

Hiroi M, Matsui S, Kubo R, Iida N, Noda Y, Kanda T, et al. Factors for Occurrence of Extended-Spectrum ^|^beta;-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli in Broilers. J Vet Med Sci. 2012;74(12):1635–7. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.11-0479.

Laube H, Friese A, von Salviati C, Guerra B, Kasbohrer A, Kreienbrock L, et al. Longitudinal Monitoring of Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase/AmpC-Producing Escherichia coli at German Broiler Chicken Fattening Farms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(16):4815–20. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00856-13.

Laube H, Friese A, von Salviati C, Guerra B, Rösler U. Transmission of ESBL/AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from broiler chicken farms to surrounding areas. Vet Microbiol. 2014;172(3–4):519–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.06.008.

Magiorakos A-P, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x.

Mevius D, Koene M, Wit B, van Pelt W, Bondt N. MARAN 2008 Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance and Antibiotic Usage in Animals in the Netherlands; 2008.

Mo SS, Urdahl AM, Nesse LL, Slettemeås JS, Ramstad SN, Torp M, et al. Occurrence of and risk factors for extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae determined by sampling of all Norwegian broiler flocks during a six month period. PLoS One. 2019;14(9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223074.

OSullivan M, Burnes K, Slowey R, Byrne W, Sammin D. Ireland One Health Report on Antimicrobial Use & Antimicrobial Resistance Acknowledgement.2019.https://health.gov.ie/national-patient-safety-office/patient-safety-surveillance/antimicrobial-resistance-amr-2/. Accessed 28 Oct 2021.

Petersen, C. K., Henius, A. E., Attauabi, M., & Cavaco, L. M. (2019). DANMAP 2019 - Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. file:///C:/Users/nb992/Downloads/DANMAP_2019.pdf

Pietsch M, Irrgang A, Roschanski N, Brenner Michael G, Hamprecht A, Rieber H, et al. Whole genome analyses of CMY-2-producing Escherichia coli isolates from humans, animals and food in Germany. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4976-3.

Projahn M, Daehre K, Roesler U, Friese A. Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamaseand plasmid-encoded cephamycinaseproducing enterobacteria in the broiler hatchery as a potential mode of pseudovertical transmission. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017a;83(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02364-16.

Projahn M, Daehre K, Roesler U, Friese A. Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamaseand plasmid-encoded cephamycinaseproducing enterobacteria in the broiler hatchery as a potential mode of pseudovertical transmission. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017b;83(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02364-16.

Reich F, Atanassova V, Klein G. Extended-spectrum ß-lactamase- and ampc-producing enterobacteria in healthy broiler chickens, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(8):1253–9. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1908.120879.

Roth N, Hofacre C, Zitz U, Mathis GF, Moder K, Doupovec B, et al. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli in broilers challenged with a multi-resistant E. coli strain and received ampicillin, an organic acid-based feed additive or a synbiotic preparation. Poult Sci. 2019;98(6). https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pez004.

Smet A, Martel A, Persoons D, Dewulf J, Heyndrickx M, Catry B, et al. Diversity of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and class C β-lactamases among cloacal Escherichia coli isolates in Belgian broiler farms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(4):1238–43. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01285-07.

Tang KL, Caffrey NP, Nóbrega DB, Cork SC, Ronksley PE, Barkema HW, et al. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planetary Health. 2017;1(8):e316–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30141-9.

van de Ven LJF, van Wagenberg AV, Debonne M, Decuypere E, Kemp B, van den Brand H. Hatching system and time effects on broiler physiology and posthatch growth. Poult Sci. 2011;90(6):1267–75. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2010-00876.

Wang J, Gibbons JF, McGrath K, Bai L, Li F, Leonard FC, et al. Molecular characterization of bla ESBL -producing Escherichia coli cultured from pig farms in Ireland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(11). https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw278.

WHO (2003). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World Health Organization World Organization for Animal Health Joint FAO/OIE/WHO Expert Workshop on Non-Human Antimicrobial Usage and Antimicrobial Resistance: Scientific assessment.

World Health Organisation (2021). WHO. 10 Global Health issues to track in 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/10-global-health-issues-to-track-in-2021. Accessed 23 Nov 2021.

Zurfluh K, Wang J, Klumpp J, Nüesch-Inderbinen M, Fanning S, Stephan R. Vertical transmission of highly similar blaCTX-M-1-harboring IncI1 plasmids in Escherichia coli with different MLST types in the poultry production pyramid. Front Microbiol. 2014;5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00519.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance and participation of the poultry company and contract farmers involved in this project. We wish to thank Dr Kaye Burgess, Teagasc Food Research Centre, Ashtown, Dublin, for her helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research project Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Animal Production (AMURAP) from Department of Agriculture, Food, & the Marine (DAFM). (Grant number 15 S 676).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NB collected samples, conducted all the laboratory work and wrote and drafted this manuscript, with input from FL, EGM, LON, JCD and AV. Study design by EGM and FL. JCD collected samples from the farms. Analysis by NB and EGM. Data visualisation by NB, LON and JCD. LON and AV contributed their knowledge and time to the laboratory work. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not necessary as the animals used for this study were not manipulated for the collection of environmental or faecal samples taken from the broiler house floor. All farmers volunteered to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Byrne, N., O’Neill, L., Dίaz, J.A.C. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from on-farm and conventional hatching broiler farms in Ireland. Ir Vet J 75, 7 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13620-022-00214-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13620-022-00214-9