Abstract

Key message

Black spruce (Picea mariana (Mill.) B.S.P.) has historically self-replaced following wildfire, but recent evidence suggests that this is changing. One factor could be negative impacts of intensifying fire activity on black spruce seed rain. We investigated this by measuring black spruce seed rain and seedling establishment. Our results suggest that increases in fire activity could reduce seed rain meaning reductions in black spruce establishment.

Context

Black spruce is an important conifer in boreal North America that develops a semi-serotinous, aerial seedbank and releases a pulse of seeds after fire. Variation in postfire seed rain has important consequences for black spruce regeneration and stand composition.

Aims

We explore the possible effects of changes in fire regime on the abundance and viability of black spruce seeds following a very large wildfire season in the Northwest Territories, Canada (NWT).

Methods

We measured postfire seed rain over 2 years at 25 black spruce-dominated sites and evaluated drivers of stand characteristics and environmental conditions on total black spruce seed rain and viability.

Results

We found a positive relationship between black spruce basal area and total seed rain. However, at high basal areas, this increasing rate of seed rain was not maintained. Viable seed rain was greater in stands that were older, closer to unburned edges, and where canopy combustion was less severe. Finally, we demonstrated positive relationships between seed rain and seedling establishment, confirming our measures of seed rain were key drivers of postfire forest regeneration.

Conclusion

These results indicate that projected increases in fire activity will reduce levels of black spruce recruitment following fire.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Wildfire is the primary large-scale disturbance in the boreal forest where it is a major determinant of forest age structure, species composition, and carbon stocks and fluxes (Bond-Lamberty et al. 2007; Beck et al. 2011). As a result of a changing climate and associated warming and drying at high northern latitudes (Johannessen et al. 2016), the frequency of extreme fire weather is projected to increase (Wang et al. 2017), altering the historic fire regime outside the norms to which biota are adapted (Flannigan et al. 2009; Seidl et al. 2017). Consequently, an increase in the frequency of large, severe crown fires is projected through the twenty-first century (Wotton et al. 2017), leading to an increase in the mean annual area burned (Wang et al. 2022). Many of these predicted changes are already apparent; for example, annual area burned in Canada surpassed the 31-year average for 6 years of the 11-year period 2010–2020 (Canadian Forest Service 2018). Understanding the impacts of large, severe fires on the population dynamics of tree species is essential to predict the structure and composition of boreal forests and the ecosystem services that they provide.

Black spruce (Picea mariana (Mill.) B.S.P.) is one of the most widespread and abundant tree species in boreal forests of North America. This species is adapted to boreal fire regimes through its semi-serotinous cones which maintain an aerial seedbank in the tree crowns. Fire is the main trigger for seed release, which is relatively low in unburned trees (Zasada et al. 1992; Arseneault 2001). The majority of black spruce seed dispersal occurs in the first 2 years following fire (Charron and Greene 2002; Greene et al. 2013). This initial seed rain results in a large recruitment pulse (Greene et al. 1999), which supports black spruce self-replacement after fire (as reviewed in Johnstone et al. 2010). The supply of viable seeds is an important factor limiting postfire seedling establishment and subsequent patterns of stand development (Greene et al. 1999; Johnstone et al. 2004; Brown and Johnstone 2012; Day et al. 2022).

Following Whelan (1995), by “fire regime”, we mean the quantified characteristics of the fires that occur in a region, including frequency, size, intensity, severity, cause, season of burning, and type (i.e. ground, surface, or crown). Of these, increases in the severity, frequency, or size of fires could reduce both the rate and viability of postfire black spruce seed rain, thereby reducing seedling recruitment through several processes. First, high fire intensity or severity can increase canopy combustion and reduce recruitment by heat-induced damage to embryos within seeds or by partially or completely combusting the seedbank (Arseneault 2001; Johnstone et al. 2009; Splawinski et al. 2019). Second, because the production of viable seeds is positively related to tree age and basal area (Greene and Johnson 1999; Viglas et al. 2013), we expect that increases in fire frequency should result in a higher proportion of younger stands burning; this would tend to reduce postfire seed availability and recruitment in the long run. Third, as fire size increases, the distances from burned to unburned areas on the perimeter of or within the burn may also increase. Although seed fall rates from unburned black spruce are thought to be relatively low, and mean seed dispersal distance is also low (Payandeh and Haavisto 1982; McCaughey et al. 1986), the contribution from these sources may not be negligible. For example, Johnstone et al. (2009) found significant decreases in seed rain with distance from unburned edges for black spruce in interior Alaska. Therefore, an increase in fire size may reduce postfire seed availability and recruitment rates.

Environmental constraints may also mediate patterns of seed rain following fire via site productivity. For species with an aerial seedbank, such as black spruce, the size of the seedbank is positively correlated with site productivity (Greene and Johnson 1999; Turner et al. 2007). Conditions that lead to decreased black spruce productivity can also reduce postfire recruitment rates (Harper et al. 2005). For example, productivity and hence seed availability are expected to be highest on mesic sites (i.e. sites with moderate soil moisture), where moisture and/or nutrient limitations are less acute than on very dry or very wet sites (Bridge and Johnson 2000).

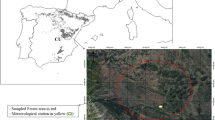

In 2014, wildfires burned 2.85 million hectares of forest in the NWT (Walker et al. 2018b); this was the largest annual area burned on record for the territory (Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre 2014). These wildfires provided an opportunity to assess the implications of a changing fire regime for postfire black spruce regeneration under conditions that, however extreme relative to the recent historical record, may be indicative of what may be expected later in this century (Wang et al. 2022). Based on the current state of knowledge, we hypothesized that higher levels of total black spruce seed rain and viability would occur at burned locations that (i) have relatively low levels of canopy combustion; (ii) have experienced longer fire-free intervals (i.e. older stand ages); (iii) are closer to unburned edges; (iv) have higher black spruce productivity; (v) have greater prefire basal area of black spruce; and (vi) have moderate soil moisture conditions (mesic). To test these hypotheses, we established a network of 250 seed traps deployed in 25 plots within three large 2014 fire scars in the Taiga Plains ecozone in the NWT (Fig. 1). This work will help support predictions of future responses and regeneration trajectories of boreal tree species to ongoing changes in fire activity.

Locations of black spruce-dominated sampled plots that burned in 2014 and where seed traps were deployed, and seedling counts performed. Plots are located in three burn complexes (yellow shading) along the road corridor between Behchokǫ̀ and Hay River, Northwest Territories, Canada and are within the Taiga Plains ecozone (green shading in the inset)

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study region

This study took place in the Taiga Plains ecozone (Ecosystem Classification Group 2007) in the NWT, Canada (Fig. 1). The Taiga Plains is 45% forested, 32% wetlands/waterbodies, and 23% barren lands and grasslands (Environment and Natural Resources 2015). Forests are composed of closed to open canopies of mixed and pure stands of black spruce, jack pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.), white spruce (Picea glauca (Moench) Voss), trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera Marshall and Betula neoalaskana Sarg.). The Taiga Plains ecozone is mainly flat with extensive peatland coverage, level to undulating uplands, and is underlain by glacial till (Ecosystem Classification Group 2007). This region is within the zone of discontinuous permafrost (Heginbottom et al. 1995). Mean annual air temperature (1981–2010) for the Yellowknife and Hay River weather stations was −4.3 °C and −2.5 °C, respectively (Environment Canada 2017). The mean January and July air temperatures were −25.6 and 17.0 °C for Yellowknife and −21.8 °C and 16.1 °C for Hay River. Mean annual precipitation (1981–2010) was 289 mm for Yellowknife and 336 mm for Hay River (Environment Canada 2017).

2.2 Estimation of seed rain

Seed rain was measured at 25 black spruce-dominated plots within three burn scars (Fig. 1). We selected burned plots from a larger set of plots with road access to represent areas that were black spruce-dominated before fire and captured gradients of fire severity and site drainage (Walker et al. 2018a). Each plot was a 2 × 30 m belt transect. At each plot, 10 traps were positioned at 3 m intervals along the transect (Figure 5 in Appendix) and secured with a large nail in each corner (250 traps in total). Traps were rectangular garden flats (52 cm × 22.5 cm) with drainage holes, lined with synthetic turf to trap the seeds. Turf was approximately 6 mm high and was used to prevent seeds from being blown out of traps by wind (Zasada et al. 1979); this design follows Johnstone et al. (2009). Traps were deployed in June 2015, and the order of deployment and collection was consistent for each sampling period to standardize sampling lengths. Seed traps were left out from June 2015 to August 2016 and emptied three times: first summer after fire (late June to late August 2015), second winter after fire (late August 2015 to mid-May 2016), and second summer after fire (mid-May 2016 to late August 2016). The timing of these collections was meant to ensure that seeds were not left in the field too long which could compromise viability. Upon collection, the contents of each seed trap were stored on ice in the field, frozen at a base camp in Fort Providence to prevent germination, and then shipped by air in coolers to Wilfrid Laurier University. In the lab, seeds from each trap were separated from organic debris, classified by tree species, and the total number of seeds by species per trap was recorded, providing an estimate of total seed rain per trap. Sorted seeds were stored at −2 °C until germination trials. There was no evidence of seed predation in the field or of fungal infection in the field or the lab.

The number of viable black spruce seeds was measured per trap, following Leadem et al. (1997). Seeds were surface disinfected by immersing in 3% H2O2 for 5 min, rinsed three times with de-ionized water, and then stratified at 4 °C for 3 weeks. Seeds were placed on moist filter paper in parafilm-sealed Petri dishes to germinate in a greenhouse for 21 days. Greenhouse photoperiod and temperature were 16/8 h day/night and 23/19 °C day/night, respectively. Seeds from each trap and period were germinated in separate petri dishes. Dishes were checked daily to ensure sufficient moisture, and water was added as necessary. Germinants were counted after 21 days. No seeds were lost to fungal infection or rot over the course of the germination trials. Viability of a subsample of ungerminated seeds (up to 10 seeds per sample) was assessed by sectioning and staining with tetrazolium chloride following (Leadem 1984) (see Appendix for additional details). We detected no viable ungerminated seeds, indicating that our germination assay was a good estimate of seed viability.

2.3 Plot-level attributes

We measured or calculated the following variables at each plot: soil moisture class, distance to the nearest unburned edge, time after previous fire in years (stand age), tree productivity index, canopy combustion, prefire standing black spruce basal area (m2 ha−1), density of prefire black spruce stems, and postfire black spruce seedling counts. Plot soil moisture class was assessed in the field following Johnstone et al. (2008). Our plots fell within three moisture categories: wet (mesic-subhygric, n = 8), with considerable surface moisture associated with depressions or concave toe slopes; mesic (n = 7), with moderate surface moisture on flat terrain or shallow depressions, including toe slopes; and dry (mesic-subxeric, n = 10), with less surface moisture on flat to gently sloping terrain. To estimate distance from the centre of each plot to the nearest unburned edge, we found the nearest edge by helicopter and took GPS coordinates while directly overhead.

All prefire trees that reached breast height (1.3 m) were identified, and diameter at breast height (DBH) measured within the 2 m × 30 m belt transect. Trees that were alive prefire consistently retained their bark, and there was no combustion of the bole allowing for distinction between trees that were standing dead prefire and those that were alive prefire. Basal area of each tree in the transect was calculated as BA = π (DBH/2)2, and plot basal area was estimated by summing stem basal area over all black spruce stems within plots. We used standing black spruce basal area rather than total black spruce basal area (standing + downed) as a predictor variable in the models because standing basal area was more strongly related to total seed rain than was total black spruce basal area (data not shown), supporting previous findings (Johnstone et al. 2009). From this, we could also determine prefire stem density (stems ha−1) for the stand and for each species individually.

Canopy combustion for each tree measured within this transect was categorized in the field on a four-point scale: 0 — alive (no combustion); 1 — low combustion (only needles combusted); 2 — moderate combustion (many small branches remaining); and 3 — high combustion (only central trunk and branch stubs remaining). We used the modal value of tree-level canopy combustion for black spruce trees within plots as our plot-level measure of canopy combustion.

Stand age at time of burning in 2014 (i.e. time after previous fire) was determined at each plot using tree ring counts. Five trees representative of the size and species of trees found before the fire in each plot were determined by taking either a cross-sectional sample (tree disk) or an increment core as close to the base as possible. Tree disk and core samples were sanded with a progressively finer grit until all rings were visible. The samples were then scanned and rings counted using Cybis CooRecorder v.7.8 (Larsson 2006) or WinDendro 2009 (Regent Instruments, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada). Tree ages within a plot were inspected for clustering, since it was expected that tree age would cluster around the date of postfire recruitment. When most trees (> 50%) fell within 10–20 years of a central date, we assumed this to indicate the most recent fire, and the age of the oldest tree in the cluster was used to represent stand age (see Walker et al. 2018a); 21 of 25 plots showed this clustered age distribution. In the absence of such clusters, we used the age of the oldest stem to represent stand age.

We used an index derived from tree size and age as a proxy for average tree productivity within a plot. Tree-level productivity was estimated as the deviance from a linear regression of basal diameter versus tree age for our sample of black spruce trees aged using basal ring counts described above. Trees with a positive or negative deviation were interpreted as indicating relatively above or below average growth, respectively, for their age. The mean of tree-level deviances for each plot was calculated to produce a plot-level productivity index.

2.4 Estimation of total seedling recruitment

Total seedling recruitment was sampled in five 1 m2 vegetation sampling quadrats spaced at 6 m intervals along one transect in each plot (Figure 5 in Appendix). Seedling counts took place in June 2016, 1 year after our seed traps were established (Table 1), approximately 2 years postfire. The seedling counts reflected cumulative black spruce regeneration from immediately postfire, up to the date of seed trap deployment, and continuing past the end of the second seed trapping period.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 (R Core Development Team 2017). Data were organized, and graphs were created using tidyverse, plyr, and ggplot2 R packages. All traps were established within black spruce-dominated plots, and most trapped seeds were black spruce (see Section 3), so this was the only species modelled. Traps that were directly below the cone ball of a fallen black spruce tree had abnormally high seed counts and were excluded from analyses. Traps that were lost or destroyed in one or more of the three collection periods were also excluded. Our total sampling effort was 247 traps within 25 plots across the three sampling periods. For analysis, we summed trap-level seed counts in each trap across the three sampling periods, yielding total seed counts per trap over 60 consecutive weeks postfire. Data are available in Baltzer et al. (2020) and Reid et al. (2022).

We tested our hypotheses of factors affecting total number of seeds and viability by fitting two generalized linear or generalized linear mixed-effects models using lme4 R package (Bates et al. 2015). First, we modelled the total number of seeds per trap as overdispersed count data (model 1) using a generalized linear mixed effects model with a negative binomial distribution, logarithmic link, and a random intercept for plot to account for nonindependence of traps within plots. We included an offset term of log(trap area × 60), where trap area is 0.117 m2 and 60 is the total number of weeks of the three collection periods. With this offset, the model predicts mean seed-fall rates in units of seeds m−2 week−1. We used package lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) to fit this model. Model diagnostics testing for outliers, zero inflation, and overdispersion was performed using package DHARMa (Hartig 2020); these tests showed that model assumptions were not violated. Marginal R2 (fixed effects only) and conditional R2 (fixed and random effects) were calculated using package MuMIn (Bartoń 2019). Second, we modelled seed viability as the probability of germination per trap (model 2) using a binomial generalized linear mixed effects model with logit link and a random intercept for plot. The response variable was the proportion of viable seeds per trap over the three sampling periods. Only data from traps with a nonzero total seed counts were included (n = 238). We fitted model 2 using R package lme4 (Bates et al. 2015), with diagnostics and R2 values derived as per model 1. For both models, predictors included distance to nearest unburned edge, standing black spruce basal area, stand age, plot productivity index, plot moisture class, and canopy combustion. Continuous predictors were standardized to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one, so that estimated coefficients and effect sizes were comparable across predictors. Moisture class was represented as a three-level factor using treatment contrasts, with the mesic class as the reference level. We characterized canopy combustion as a two-level factor using treatment contrasts, with the moderate combustion class as the reference level. Predictors were not strongly pairwise correlated (r < 0.50). To account for possible nonlinearities in the total and viable seed rain response, we compared alternative full-saturated models including linear or spline adjustments (with up to two degrees of freedom) for each continuous predictor. We selected the adjustment with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) score as being the best supported model corrected for parsimony (Crawley 2013).

To test that our seed trap data were informative with respect to black spruce, we modelled black spruce seedling counts measured 2 years postfire. The seedlings were counted in five 1 m2 quadrats along one 30 m transect at each of the sites where seed traps were established (see Day et al. 2022 for full details of seedling counts). It was not possible to pair seed traps with vegetation quadrats within sites, so we calculated plot-level means of black spruce seedlings per quadrat and of total and viable black spruce seeds per trap, standardized to counts per square meter. Equivalently, the three counts were standardized to sample mean densities. We then regressed seedling density against total seed density (model 3a) and viable seed density (model 3b). We used linear models with spline adjustments of up to three degrees of freedom to model possible non-linear responses. We selected the adjustment with the lowest AIC score to determine the appropriate spline adjustment. We calculated raw and adjusted R2 for the selected models.

3 Results

The 247 seed traps collected a total of 3814 seeds over the 60 weeks. Most seeds (95%) were black spruce. Other tree species captured were trembling aspen (3.62%), jack pine (0.87%), and paper birch (0.16%). The mean number of black spruce seeds collected was 14.6 seeds per trap (range: 0–57, Table 4 in Appendix). Given the trap area of 0.117 m2 and 60-week collection period, the mean black spruce seed rain was 2.2 seeds m−2 week−1. Of the 247 traps, 238 (74.8%) had nonzero total black spruce seed counts.

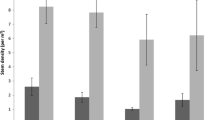

Overall, we found there were different significant predictors for total and viable seed rain. Total black spruce seed rain (scaled to m2 week−1; model 1) was significantly associated with standing black spruce basal area (Table 2; Fig. 2). Model selection supported a hump-shaped relationship between seed rain and basal area (spline adjustment of two degrees of freedom) rather than a linear relationship (Table 5 in Appendix). Total seed rain increased with basal areas up to ~12 m2 ha−1, after which this increase did not continue in plots with larger basal areas. There was also a significative positive association of total seed rain with the productivity index. Plots with moderate combustion appeared to have greater total seed rain compared to high combustion, but this factor was not significant. There were no significant effects for time after fire, site moisture class, or distance to edge, on total seed rain. Model 1 R2m (marginal R2; fixed effects only) was 0.42, and the R2c (conditional R2; fixed and random terms) was 0.65.

Predicted total black spruce seed rain as a function of prefire black spruce basal area (A) and productivity index (B), at two canopy combustion levels (model 1, Table 2). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Values of other continuous covariates were held constant at their mean or reference levels

Our germination trials showed that 498/3637 black spruce seeds were viable (13.7%). The number of viable seeds per trap ranged from 0 to 15 (mean ± standard deviation: 2.02 ± 2.29, Table 4 in Appendix), and the proportion of viable seeds per trap ranged from 0 to 1.0 (mean ± standard deviation: 0.17 ± 0.21). Germination probability increased with stand age, but not with standing black spruce basal area (model 2; Table 2, Fig. 3). Model selection supported a hump-shaped relationship between seed viability and distance to edge (spline adjustment of two degrees of freedom) rather than a linear relationship (Table 5 in Appendix). Thus, seed viability was greater in plots closer to an unburned edge (~100–200 m; Fig. 3B). Soil moisture was also a significant predictor with seed viability being highest on wet compared to mesic or dry sites. There was a marginally significant negative effect of canopy combustion on seed viability with higher canopy combustion trending toward lower seed viability compared to moderate combustion. Model R2m for the seed viability model (marginal R2; fixed effects only) was 0.23, and the R2c (conditional R2; fixed and random terms) was 0.29.

Predicted probability of black spruce seed viability as a function of prefire stand age (a) and distance to unburned edge (b) at two levels of canopy combustion levels and three levels of moisture regime (model 2; Table 2). Values of other continuous covariates were held constant. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals

The analysis of plot-level seedling regeneration showed that density of black spruce seedlings was positively related to both total and viable seed rain (model 3; Table 3, Fig. 4). However, the variation explained by the model including total seed rain as a predictor was higher than the model including viable seed rain (Table 3). Both models displayed a concave relationship (spline adjustment with 2 degrees of freedom, Table 6 in Appendix); seedling densities increased with total or viable seed rain up to ~200 seeds m−2 or ~20 seeds m−2, respectively, after which further increases in both seed rain variables led to no further significant increases in seedling establishment (Table 3; Fig. 4).

Predicted black spruce seedlings (m−2) as a function of total seed rain (A) and viable seed rain (B) for 25 plots. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Model fits are presented in Table 3

4 Discussion

Our models of black spruce seed rain and seed viability in boreal forests of the Northwest Territories (NWT), Canada, confirmed expected positive relationships between standing black spruce basal area and postfire total seed rain. However, these relationships were non-linear: this increase in postfire seed availability is not maintained at high basal areas. Contrary to our expectations, high canopy combustion was not a significant predictor of total seed rain and only had a marginal negative effect on postfire seed viability. As expected, seed viability rates were greater in older sites and closer to unburned edges and, surprisingly, were higher in wet than in dry or mesic sites. Finally, seedling densities were related to both total and viable seed rain, with the highest levels of recruitment corresponding with moderate levels of total and viable seed counts, suggesting that beyond a certain level of seed rain, other factors become limiting to establishment.

The concave relationship between site black spruce basal area and total seed rain has not previously been reported to our knowledge. Basal area has been shown to be a principal mechanism supporting black spruce self-replacement after fire across North America (Greene and Johnson 1999; Johnstone et al. 2009; Splawinski et al. 2016). In serotinous conifers, greater prefire basal area translates into larger aerial seedbanks (Greene and Johnson 1999), thus supporting ample seed rain following fire. This is an example of a positive neighbourhood effect that promotes stand self-replacement and regeneration after disturbance (Frelich and Reich 1999), which may be particularly important for seeds with low dispersal distances such as black spruce. Our findings support this mechanism; however, our data also suggest that when basal area gets too high, reproductive outputs can be negatively impacted. The lack of continued increase in seed rain at basal areas greater than ~12 m2 ha−1 could be due to negative effects of competition on reproductive outputs (e.g. Rossi et al. 2012). To evaluate this, we investigated relationships between our site productivity index, density of black spruce stems, and basal area (Figure 6 in Appendix). While stem density was significantly negatively correlated with the productivity index, a concave relationship existed between basal area and both stem density and site productivity. This meant that the plots with highest productivity had both moderate stem densities and basal areas, which corresponded with the plots with the greatest reproductive outputs (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that our range of sampled sites included many with high basal areas compared to other studies (range: current study, 1.4–37.1 m2 ha−1; Johnstone et al. 2009, 0.1–28 m2 ha−1; Zasada et al. 1979, 1.8–6.9 m2 ha−1), which may explain why a concave response was not detected in previous studies. Thus, our study has added knowledge of basal area relationships in seed rain that have not been captured previously.

Although seeds may be directly destroyed by high severity fire in the tree canopy (Arseneault 2001; Splawinski et al. 2019) leading to reduced total or viable seed rain, we did not find evidence of reduced total seed rain in the present study. However, our models indicate that severe canopy combustion marginally reduced seed viability. This finding supports previous studies from other regions in North America that greater combustion results in lower seed viability either at the individual level (Johnstone et al. 2009) or in response to within-crown variability in combustion (Splawinski et al. 2019). Other studies have also found that severe canopy combustion may reduce viable seed rain with no apparent impact on total seed rain (e.g. Johnstone et al. 2009), suggesting that loss of seed viability due to heating associate with greater canopy combustion may be a more common mechanism of reduced reproductive potential than complete combustion of seeds or cones.

The positive relationship between stand age and seed viability suggests that shortened fire return intervals may negatively impact postfire regeneration of black spruce in the NWT. Our study provides an underlying mechanism for previous findings of reduced black spruce seedling density in areas experiencing more frequent stand replacing fires in the NWT (Whitman et al. 2019, Day et al. 2022) and Yukon (Brown and Johnstone 2012). With the increased fire activity predicted for the boreal biome (de Groot et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2022), the average age at which stands burn must necessarily decrease, which will have wide-ranging impacts in these forests. As stands age, the accumulation of black spruce basal area slows and can even decrease as uneven age- and size-class structures develop (Miquelajauregui et al. 2016). This decoupling between age and basal area may explain the differential responses we observed for total and viable seed rain to these predictors. Specifically, our results suggest that basal area is an important determinant of total seed rain, but that the age of the stand is more relevant for determining how much of this seed will be viable, a critical component of regeneration.

The greater viability rate of seeds on wet plots was unexpected. Wet sites with thick organic soils are stressful locations from a growth perspective, meaning trees may increase allocation to reproductive output. Indeed, greater reproductive efforts in trees are favoured in response to other resource-related mechanisms, such as shade (Paz and Martínez-Ramos 2003; Quero et al. 2007) and intraspecific resource competition (Lebrija-Trejos et al. 2016). Indirectly, it is possible that differences in fire behaviour and cone heating amongst plot moisture classes not captured in our canopy combustion estimates explain this finding. Other things being equal, elevated soil moisture is associated with lower rates of fuel consumption (Forestry Canada Fire Danger Group 1992) and hence with lower fire intensity. Lower fire intensity would reduce scorch height (Van Wagner 1973), and presumably the amount of heating experienced by cones, thereby helping to maintain seed viability.

Distance to unburned edge was a significant positive predictor of seed viability, but not of seed rain. These findings align with previous studies of seed rain in interior Alaska (Johnstone et al. 2009). We found that seed viability declined up to distances of ~100–200 m from an edge, after which it remained constant (Fig. 3B); this is consistent with the previously measured dispersal distances of approximately 100–120 m (Payandeh and Haavisto 1982; McCaughey et al. 1986). This implies that contributions of viable seed from relatively distant unburned sources can affect regeneration of this species. Large fires are common in the NWT and are expected to become even more common under climate warming (Amiro et al. 2004; Burton et al. 2008). Our findings suggest a moderate negative impact of large fire complexes on postfire regeneration in black spruce.

It is notable the models of total seed rain and of seed viability identified different significant covariates. Seed rain and viability are only the first of multiple limiting factors in postfire regeneration; actual germination of viable seed on suitable substrate, seedling establishment, and survival to maturity is also important (Greene et al. 2007; Brown et al. 2015). The concave relation of seedlings to seed rain implies that seed supply is not limiting on all sites. Our results address the initial stages of this complex chain of processes and provide novel information regarding postfire regeneration in the extensive black spruce forests of the NWT. The implications are that regeneration depends on fairly local properties of stand structure (i.e. both stand age and basal area), on stand-level moisture/drainage, and also on the level of canopy combustion, which interacts with stand structure in boreal black spruce forests (Miquelajauregui et al. 2016). Vegetation dynamics models that do not consider these local phenomena may be inadequate to forecast future forest conditions in these regions.

Our data and models are of ecological relevance insofar as they inform on drivers of black spruce regeneration postfire. However, we may also have missed temporal variation in seed rain and seed viability due to constraints in our experimental design. The period of postfire seed dispersal from black spruce is brief; a large majority of seed rain occurs in the first two growing seasons following fire (Charron and Greene 2002), resulting in a large recruitment pulse (Greene et al. 1999). In addition, seeds released in the first months after fire may come preferentially from cones at the periphery of tree crowns. These seeds might have lower viability than later-falling seeds from more protected, interior cones (Splawinski et al. 2019). Earlier seed trap deployment and more regular seed trap emptying would indicate the timing of release of the ‘most’ and ‘least’ viable seed and reduce seed loss or viability reduction by shortening the length of time seeds are left in traps. Data from earlier seed trap deployments might also reveal whether there is an absolute difference in number of seeds released from coneballs experiencing high vs. low combustion. To capture all postfire seed rain, traps would need to be deployed immediately after late-burning fires are extinguished by the onset of winter snow, which creates logistical challenges difficult to overcome in any study (e.g. Johnstone et al. 2009). By starting in June 2015, our study may have missed upwards of 50% of the total seed rain attributable to the 2014 fires (Greene et al. 2013). However, despite missing this early period of seed rain, our data show significant relationships between black spruce seedling establishment and both total and viable seed rain, suggesting that our estimates of seed rain are meaningful from an ecological perspective.

5 Conclusion

Our findings both support and extend previous work in the North American boreal forest showing that total and viable black spruce seed rain are driven by various combinations of standing basal area, distance to an unburned edge, stand age, and canopy combustion severity (Zasada et al. 1979; Arseneault 2001; Johnstone et al. 2009). Importantly, we also show the relevance of these measures for natural seedling establishment. Taken together, these results suggest that black spruce recruitment after fire may decline under projected increases in fire activity in this region (Wotton et al. 2017), most notably fire frequency and to a lesser extent fire size. Indeed, there is already evidence of changing regeneration patterns in black spruce across much of boreal North America (Baltzer et al. 2021). The non-linear nature of several of the modelled relationships highlights the importance of capturing broad environmental, stand structural, and climatic gradients to better reflect complex ecological relationships. Further exploration of non-linearities between key measures of forest recovery and environmental or stand characteristics, such as those identified here, will help to refine projections of postfire forest recovery. As the fire regime continues to change, there is an increased need for detailed and generalizable understanding of the responses of dominant boreal forest species to such changes, to support predictive modelling of the future state of this vast and globally important biome.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study can be found in Reid et al. (2022) https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.z8w9ghxg4 and Baltzer et al. (2020) https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.76hdr7sth.

References

Amiro B, Logan, Wotton M et al (2004) Fire weather index system components of large fires in the Canadian boreal forest. Int J Wildland Fire 13:391–400

Arseneault D (2001) Impact of fire behavior on postfire forest development in a homogeneous boreal landscape. Can J For Res 31:1367–1374. https://doi.org/10.1139/x01-065

Baltzer JL, Day NJ, Walker XJ et al (2021) Increasing fire and the decline of fire adapted black spruce in the boreal forest. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118:e2024872118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024872118

Baltzer JL, Day NJ, White A et al (2020) Vascular plant community data for Northwest Territories, Canada. Dryad Dataset. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.76hdr7sth

Bartoń K (2019) MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R package version 1.43.15

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48

Beck PSA, Goetz SJ, Mack MC et al (2011) The impacts and implications of an intensifying fire regime on Alaskan boreal forest composition and albedo: fire regime effects on boreal forests. Glob Chang Biol 17:2853–2866. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02412.x

Bond-Lamberty B, Peckham SD, Ahl DE, Gower ST (2007) Fire as the dominant driver of Central Canadian boreal forest carbon balance. Nature 450:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06272

Bridge S, Johnson E (2000) Geomorphic principles of terrain organization and vegetation gradients. J Veg Sci 11:57–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/3236776

Brown CD, Johnstone JF (2012) Once burned, twice shy: repeat fires reduce seed availability and alter substrate constraints on Picea mariana regeneration. For Ecol Manag 266:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2011.11.006

Brown CD, Liu J, Yan G, Johnstone JF (2015) Disentangling legacy effects from environmental filters of postfire assembly of boreal tree assemblages. Ecology 96:3023–3032. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-2302.1

Burton PJ, Parisien M-A, Hicke JA, Hall RJ, Freeburn JT (2008) Large fires as agents of ecological diversity in the North American boreal forest. Int J Wildland Fire 17:754–767. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07149

Canadian Forest Service (2018) National Forestry Database. http://nfdp.ccfm.org

Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (2014) Situation Report - Sep 22, 2014. http://www.ciffc.ca/firewire/current.php?lang=%0Aen&date=20140922 [Verified 21 December 2017]

Charron I, Greene DF (2002) Post-wildfire seedbeds and tree establishment in the southern mixedwood boreal forest. Can J For Res 32:1607–1615. https://doi.org/10.1139/x02-085

Crawley MJ (2013) The R book, 2nd edn. Wiley, Chichester

Day NJ, Johnstone JF, Reid KA, Cumming SG, Mack MC, Turetsky MR, Walker XJ, Baltzer JL (2022) Material legacies and environmental constraints underlie fire resilience of a dominant boreal forest type. Ecosystems, in press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-022-00772-7

de Groot WJ, Flannigan MD, Cantin AS (2013) Climate change impacts on future boreal fire regimes. For Ecol Manag 294:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.09.027

Ecosystem Classification Group (2007)(rev. 2009). Ecological Regions of the Northwest Territories - Taiga Plains. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Government of the Northwest Territories. Yellowknife; p. 173

Environment and Natural Resources (2015) 14.1 Land cover type by ecozones. In: State of the environment 2015 http://www.enr.gov.nt.ca/state-environment

Environment Canada (2017) Canadian climate normals 1981-2010 station data. http://climate.weather.gc.ca

Flannigan MD, Krawchuk M, de Groot W et al (2009) Implications of changing climate for global wildland fire. Int J Wildland Fire 18:483–507. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF08187

Forestry Canada Fire Danger Group (1992) Development and structure of the Canadian forest fire behavior prediction system. In: Inf. Rep. ST–X–3. Forestry Canada Science and Sustainable Development Directorate, Ottawa

Frelich LE, Reich PB (1999) Disturbance neighborhood effects, community stability severity, and in forests. Ecosystems 2:151–166

Greene DF, Johnson EA (1999) Modelling recruitment of Populus tremuloides, Pinus banksiana, and Picea mariana following fire in the mixedwood boreal forest. Can J For Res 29:462–473. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-29-4-462

Greene DF, Macdonald SE, Haeussler S et al (2007) The reduction of organic-layer depth by wildfire in the North American boreal forest and its effect on tree recruitment by seed. Can J For Res 37:1012–1023. https://doi.org/10.1139/X06-245

Greene DF, Splawinski TB, Gauthier S, Bergeron Y (2013) Seed abscission schedules and the timing of post-fire salvage of Picea mariana and Pinus banksiana. For Ecol Manag 303:20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.03.049

Greene DF, Zasada JC, Sirois L et al (1999) A review of the regeneration dynamics of North American boreal forest tree species. Can J For Res 29:824–839. https://doi.org/10.1139/x98-112

Harper KA, Bergeron Y, Drapeau P et al (2005) Structural development following fire in black spruce boreal forest. For Ecol Manag 206:293–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2004.11.008

Hartig F (2020) DHARMa: residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level / mixed) regression models. R package version 0.3.2.0

Heginbottom J, Dubreuil M, Harker P (1995) Canada: permafrost. In: National Atlas of Canada fifth edition, MCR 4177. Natural Resources Canada.

Johannessen O, Kuzmina S, Bobylev L, Miles M (2016) Surface air temperature variability and trends in the Arctic: new amplification assessment and regionalisation. Telus A - Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr 68:28234. https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusa.v68.28234

Johnstone JF, Boby LA, Tissier E et al (2009) Postfire seed rain of black spruce, a semiserotinous conifer, in forests of interior Alaska. Can J For Res 39:1575–1588. https://doi.org/10.1139/X09-068

Johnstone JF, Chapin FS III, Foote M et al (2004) Decadal observations of tree regeneration following fire in boreal forests. Can J For Res 34:267–273. https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-183

Johnstone JF, Chapin FS III, Hollingsworth TN et al (2010) Fire, climate change, and forest resilience in interior Alaska. Can J For Res 40:1302–1312. https://doi.org/10.1139/X10-061

Johnstone JF, Hollingsworth TN, Chapin FS III (2008) A key for predicting postfire successional trajectories in black spruce stands of interior Alaska. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-767. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland, p 1–44

Larsson C (2006) CooRecorder and Cdendro programs of the CooRecorder/Cdendro package, version 7.8

Leadem C (1984) Quick tests for tree seed viability. B.C. Ministry of Forests Land management report no. 18

Leadem C, Gillies S, Yearsley H et al (1997) Field studies of seed biology. Land management handbook 40. B.C. Ministry of Forests Research Program, Victoria. pp 165.

Lebrija-Trejos E, Reich PB, Hernández A, Wright SJ (2016) Species with greater seed mass are more tolerant of conspecific neighbours: a key driver of early survival and future abundances in a tropical forest. Ecol Lett 19:1071–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12643

McCaughey W, Schmidt W, Shearer R (1986) Seed-dispersal characteristics of conifers in the inland mountain west. In: Shearer R (ed) Proceedings -- Conifer Tree Seed in the Inland Mountain West Symposium. US Forest Service General Technical Report INT-203, Missoula, pp 50–62

Miquelajauregui Y, Cumming SG, Gauthier S (2016) Modelling variable fire severity in boreal forests: effects of fire intensity and stand structure. PLoS One 11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150073

Payandeh B, Haavisto V (1982) Prediction equations for black spruce seed production and dispersal in northern Ontario. For Chron 58:96–99

Paz H, Martínez-Ramos M (2003) Seed mass and seedling performance within eight species of Psychotria (Rubiaceae). Ecology 84:439–450. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[0439:SMASPW]2.0.CO;2

Quero JL, Villar R, Marañón T et al (2007) Seed-mass effects in four Mediterranean quercus species (Fagaceae) growing in contrasting light environments. Am J Bot 94:1795–1803. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.94.11.1795

R Core Development Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing v. 3.4.2.

Reid KA, Day NJ, Alfaro-Sánchez R, Johnstone JF, Cumming SG, Mack MC, Turetsky MR, Walker XJ, Baltzer JL (2022) Black spruce seed availability and viability after fire. Dryad Dataset, Northwest Territories. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.z8w9ghxg4

Rossi S, Morin H, Laprise D, Gionest F (2012) Testing masting mechanisms of boreal forest species at different stand densities. Oikos 121:665–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19953.x

Seidl R, Thom D, Kautz M et al (2017) Forest disturbances under climate change. Nat Clim Chang 7:395–402. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3303

Splawinski TB, Gauthier S, Bergeron Y et al (2016) A landscape-level tool for assessing natural regeneration density of Picea mariana and Pinus banksiana following fire and salvage logging. For Ecol Manag 373:189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.04.036

Splawinski TB, Greene DF, Michaletz ST et al (2019) Position of cones within cone clusters determines seed survival in black spruce during wildfire. Can J For Res 49:121–127. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2018-0209

Turner MG, Turner DM, Romme WH, Tinker DB (2007) Cone production in young post-fire Pinus contorta stands in Greater Yellowstone (USA). For Ecol Manag 242:119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2006.12.032

Van Wagner C (1973) Height of crown scorch in forest fires. Can J For Res 3:373–378

Viglas JN, Brown CD, Johnstone JF (2013) Age and size effects on seed productivity of northern black spruce. Can J For Res 43:534–543. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2013-0022

Walker XJ, Baltzer JL, Cumming SG et al (2018a) Soil organic layer combustion in boreal black spruce and jack pine stands of the Northwest Territories, Canada. Int J Wildland Fire 27. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF17095

Walker XJ, Rogers BM, Baltzer JL et al (2018b) Cross-scale controls on carbon emissions from boreal forest mega-fires. Glob Chang Biol 24:4251–4265. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14287

Wang X, Parisien M-A, Taylor S et al (2017) Projected changes in daily fire spread across Canada over the next century. Environ Res Lett 12:25005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa5835

Wang X, Swystun T, Flannigan MD (2022) Future wildfire extent and frequency determined by the longest fire-conducive weather spell. Sci Total Environ 830:154752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.15752

Whelan RJ (1995) The ecology of fire, 1st edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Whitman E, Parisien MA, Thompson DK, Flannigan MD (2019) Short-interval wildfire and drought overwhelm boreal forest resilience. Sci Rep 9:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55036-7

Wotton B, Flannigan MD, Marshall G (2017) Potential climate change impacts on fire intensity and key wildfire suppression thresholds in Canada. Environ Res Lett 12:95003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7e6e

Zasada JC, Sharik T, Nygren M (1992) The reproductive process in boreal forest trees. In: Shugart HH, Leemans R, Bonan G (eds) A systems analysis of the global boreal forest. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 85–125

Zasada JC, Viereck L, Foote M (1979) Quantity and quality of dispersed seed. In: Viereck L, Dyrness C (eds) Ecological effects of the Wickersham Dome fire near Fairbanks, Alaska. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-090. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. pp 45–49.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Wilfrid Laurier University — government of the NWT Partnership Agreement for providing logistical support and laboratory space. We also thank Q. Decent, C. Dieleman, G. Degré-Timmons, J. Holloway, M. McHaffie, T. Plaskett, J. Trus, and A. White for contributions to field data collection, the numerous laboratory assistants who helped sort material from seed traps, and J. Holloway for assistance in map production.

Code availability

Not applicable. We used existing R code for all analysis.

Funding

This article is Project 170 of the Government of the Northwest Territories Department of Environment and Natural Resources Cumulative Impacts Monitoring Program (funding awarded to JLB, JFJ, and SGC). Additional funding for this research was provided by NSERC (Changing Cold Regions Network), NSERC PDF to NJD, NSERC Discovery to MRT and JFJ, Northern Scientific Training Program, NSF DEB RAPID grant no. 1542150 to MCM, NASA Arctic Boreal and Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) Legacy Carbon grant no. NNX15AT71A to MCM, and CFREF Global Water Futures — Northern Water Futures and Canada Research Chair funding to JLB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JLB, JFJ, MCM, and MRT with support from NJD, SGC, and XJW; methodology, all authors contributed; formal analysis and investigation, KAR, NJD, XJW, and RAS with support from JLB, JFJ, and SGC; writing — original draft preparation, KAR with support from JLB, NJD, JFJ, RAS, and SGC; writing — review and editing, all authors contributed; funding acquisition, JLB, JFJ, SGC, MRT, and MCM; resources, JLB, MCM, and MRT; supervision, JLB and ND. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors declare that they obtained the approval of the Government of the Northwest Territories Aurora Research Institute (Research Licenses 15879 and 16018) in consultation with the Ka’a’gee Tu First Nation, the Tłı̨chǫ Government, and the Wek'éezhìi Renewable Resources Board for conducting this study on their traditional territories.

Consent for publication

All authors gave their informed consent to this publication and its content.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Handling editor: Paulo Fernandes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Seed viability determination

To determine viable seed rain, germination trials were conducted using the sorted seeds from the seed traps. The protocol for the germination trials follows Leadem et al. (1997). Specifically, all seeds were surface sterilized by immersing them in H2O2 for 5 min and rinsed three times with de-ionized water. All seeds were then stratified by soaking for 24 h in 20–25 °C de-ionized water, following which the seeds were placed in plastic bags or vials for 21 days at 2–5 °C. Seeds were then placed on moist filter paper on Petri dishes to germinate in a greenhouse for 21 days where conditions were 23 °C for 16 h of light and 19 °C for 8 h of dark. Dishes were set up in a randomized blocking design with 10 independent blocks and dishes distributed randomly amongst blocks. Samples from each trap were tested separately unless there were more than 100 seeds in a sample in which case the sample was separated into subsamples. Dishes were checked daily to ensure sufficient moisture. At the end of the 21-day germination period, the number of germinated seeds was counted.

Viability tests were then run on a subsample of seeds that did not germinate to determine whether they are viable to germinate (i.e. filled seeds) or not. Ten ungerminated seeds from each site were tested for viability (n = 250 seeds). Protocol for the viability test follows Leadem (1984). Seeds were soaked overnight in 20 °C water to soften the tissues. A thin layer of the endosperm was sliced off, and the cut seeds were placed in Petri dishes and covered with 1% tetrazolium (TZ) solution (pH = 6.5–7). Seeds were then incubated for 2–8 h and removed when staining is complete. To determine when staining is complete, an additional dish of seeds was stained, and seeds were cut periodically to assess how far the staining has progressed and to ensure that the staining did not get too dark. When staining was complete, the TZ solution was drained, and the seeds were rinsed 2–3 times with water. Seeds were then cut in half to view the embryo. The protocol by Leadem (1984) provides figures which were then used to assess the make-up of inside of the seed and assess viability. None of the seeds that were tested for viability was viable, indicating that all seeds that were viable had germinated during the preceding experiment.

Schematic of plot design. Each plot was a pair of parallel 30 m belt transects, 2 m apart. Ten seed traps were positioned at 3 m intervals along the center line. Traps were rectangular garden flats (52 cm × 22.5 cm) with drainage holes and lined with synthetic grass turf to trap the seeds. Five of the traps were collocated with five 1 m2 quadrats where all seedlings were counted in June 2016 (squares marked S, adjacent to the right hand transect)

Relationships between standing black spruce basal area and tree productivity index (a), density of black spruce stems and tree productivity index (b), and standing black spruce basal area and density of black spruce stems (c). Regression lines are shown as black lines and cubic polynomial lines as blue lines. Insets in the panels show Pearson correlation coefficients between plotted variables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reid, K.A., Day, N.J., Alfaro-Sánchez, R. et al. Black spruce (Picea mariana) seed availability and viability in boreal forests after large wildfires. Annals of Forest Science 80, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13595-022-01166-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13595-022-01166-4