Abstract

We here describe a monospecific assemblage of giant aquatic snakes from the middle Eocene of Kpogamé, Togo. The material, consisting of large isolated vertebrae, is referred to Palaeophis africanus, an enigmatic palaeophiid species, which was so far otherwise known only from a limited number of vertebrae from the middle Eocene of Nigeria and Angola. Material from the late Eocene of the eastern USA that had been referred to the same species, is here instead considered too fragmentary for species-level determination and Palaeophis africanus is thus so far restricted to Africa. With the aid of micro-CT scanning, we present 3D models of 17 vertebrae, pertaining to different portions of the vertebral column. We provide detailed comparisons of the new material with all named African species of the genus Palaeophis. A tentative diagnosis of Palaeophis africanus is provided. With more than 50 vertebrae, the new Togolese specimens represent the most abundant known material attributed to Palaeophis africanus and significantly enhance our knowledge of the vertebral anatomy and intracolumnar variation for this taxon. Furthermore, this adds to the, as yet, extremely scarce fossil record of squamates from central western Africa, a region where Paleogene herpetofaunas are only rather poorly known.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Palaeophiids (Palaeophiidae) comprise an enigmatic lineage of snakes, which achieved a wide geographic distribution during the Paleogene, spanning across large portions of Europe, Asia, Africa, North and South America (Smith & Georgalis, in press). Among palaeophiids rank some of the largest known snakes of all time, with certain taxa reaching truly gigantic sizes (McCartney et al., 2018; Rage, 1983a, 1983b). Palaeophiids were all aquatic (or at least semi-aquatic) and inhabited a range of freshwater, estuarine, shallow marine coastal, and even open marine environments (Georgalis et al., 2020; Hoffstetter, 1958; Hutchison, 1985; Rage et al., 2003; Rage, 1983a, 1983b). Two palaeophiid genera are recognized with certainty, i.e., Palaeophis Owen, 1841, and Pterosphenus Lucas, 1898. A third genus, Archaeophis Massalongo, 1859, has been occasionally referred to this family, but this assignment should only be considered as tentative (Georgalis et al., 2020; Smith & Georgalis, in press). Both Palaeophis and Pterosphenus are known exclusively by vertebrae and ribs. The total absence of cranial elements significantly hinders a more precise understanding of their phylogenetic relationships (Georgalis et al., 2020; Smith & Georgalis, in press). As such, their affinities with other snake groups remain largely unknown and unsettled. They were originally and for a long time considered to bear affinities with boas and/or pythons (Rage, 1983a; Rochebrune, 1880), while other hypotheses placed them in their own distinct group, Cholophidia, together with a number of Cretaceous hind-limbed forms (Hoffstetter, 1939; Nopcsa, 1923a, 1923b), or even thought to be related to extant acrochordids (Wallach et al., 2014; Zvonok & Snetkov, 2012). Nevertheless, there is currently a relative consensus that palaeophiids are not related to the group encompassing boas and pythons (i.e., the Constrictores sensu Georgalis & Smith, 2020), but probably lie more basally within Alethinophidia (Georgalis et al., 2020; Head et al., 2005; McCartney & Seiffert, 2016; Rage & Werner, 1999; Smith & Georgalis, in press).

In Africa, palaeophiids have been known since the very beginning of the twentieth century (Andrews, 1901, 1906; Janensch, 1906). However, despite these early discoveries, only a few subsequent descriptions followed during the next decades, all of them originating from a small number of Paleogene localities of this continent (Andrews, 1924; Antunes, 1964; Arambourg, 1952; Folie et al., 2021; Hoffstetter, 1960, 1961; Houssaye et al., 2013, 2019; McCartney & Seiffert, 2016; McCartney et al., 2018; Rage, 1983b; Zouhri et al., 2018, 2021). Sudanese and Moroccan Cretaceous remains have been referred (or at least tentatively referred) to palaeophiids, extending the stratigraphic distribution of the group back to the Mesozoic (Rage & Werner, 1999; Rage & Wouters, 1979). Four different palaeophiid species have been established from African deposits: Palaeophis maghrebianus Arambourg, 1952, from the early Eocene of Morocco (Arambourg, 1952; Houssaye et al., 2013), Palaeophis colossaeus Rage, 1983b, from the early–middle Eocene of Mali (Houssaye et al., 2019; McCartney et al., 2018; O’Leary et al., 2019; Rage, 1983b), Palaeophis africanus Andrews, 1924, from the middle Eocene of Nigeria and Angola (Andrews, 1924; Folie et al., 2021), and Pterosphenus schweinfurthi (Andrews, 1901) from the middle–late Eocene of Egypt and Libya (Andrews, 1901, 1906; Hoffstetter, 1961; Janensch, 1906; McCartney & Seiffert, 2016).

We here describe several vertebrae from the middle Eocene (Lutetian) of Togo, an area which so far lacked Eocene snake fossil remains. The new Togolese specimens are referred to Palaeophis africanus. With the application of micro-CT scanning, 3D models of 17 vertebrae, pertaining to different portions of the vertebral column, are provided, as well as comparisons to all other African species of Palaeophis are performed. The new Togolese snake assemblage represents the most abundant material known so far for Palaeophis africanus, thus allowing a better knowledge of the anatomy and intraspecific variability of this taxon and of African palaeophiids as a whole.

Institutional abbreviations

HNHM: Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary; MDHC: Massimo Delfino Herpetological Collection, Università di Torino, Italy; MGP-PD, Museo di Geologia e Paleontologia dell’Università di Padova, Padova, Italy; MNCN, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid, Spain; MNHN, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France; NHMUK, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom; NHMW, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria; PIMUZ, Palaeontological Institute and Museum of the University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; UM, Université de Montpellier, Montpellier, France; ZPW, University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland; ZZSiD, Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences, Krakow, Poland.

Geological settings

The Togolese phosphate deposits extend from Aveta in the southwest to Dagbati in the northwest (Colonna-Cimera, 1961; Johnson, 1987; Slansky, 1962; Visse, 1957) (Fig. 1). They are now exploited by the Société Nouvelle des Phosphates du Togo (SNPT) in two quarries at Kpogamé (SW) and Dagbati (NE). Early palaeontological and sedimentological studies were carried out in the northeastern part of the Kpogamé quarry (Cappetta & Traverse, 1988; Johnson, 1987; Johnson et al., 2000). Stratigraphically, the phosphate complex overlies a lower Eocene palygorskite-rich claystone (Johnson, 1987), which constitutes the upper unit of the Tabligbo Group. The phosphate complex comprises three informal lithostratigraphic units, from the base to the top (Johnson, 1987; Slansky, 1962): the phosphatic marl (15–20 m thick), the phospharenite layer (2–8 m thick), and the phosphatic clay (0.5 to 10 m thick). The phospharenite layer is continuous laterally with calcareous phosphate in the southeast of the basin. In the 1980s, when the specimens described here were collected, the phospharenite layer included a condensed horizon in the transitional zone between the calcareous phosphate formation and phospharenite that was referred to the ‘Bone Bed du Mur’ (BBM) by Cappetta and Traverse (1988) and Gingerich and Cappetta (2014). This horizon yielded numerous fragments of internal casts of gastropods, bivalves, and nautilid fragments (Johnson, 1987; Slansky, 1962), along with a rich vertebrate fauna, including chondrichthyans and bony fishes (Cappetta & Traverse, 1988), pseudo-toothed birds (Bourdon & Cappetta, 2012), early cetaceans, sirenians, and indeterminate terrestrial mammals (Gingerich & Cappetta, 2014; Kassegne et al., 2021). Another condensed horizon resting on the carbonatized and phosphatized bed, referred to as the ‘Bone Bed reposant sur la couche carbonatée’ (BBR), also yielded similar invertebrate and vertebrate faunas (Cappetta & Traverse, 1988; Gingerich & Cappetta, 2014). Based on planktonic foraminifera, Cappetta and Traverse (1988) proposed to assign the phospharenite to the planktonic foraminiferal zone P11 (middle Lutetian, ca. 47–44 Ma: Berggren & Pearson, 2005; 46–43 Ma. Johnson (1987) , Johnson et al. (2000), and Vandenberghe et al. (2012) used bioclasts and mineralogy to characterize the depositional environment of the phosphates of Kpogamé, and proposed a shallow marine environment of average salinity with moderate deposition energy. These phosphate deposits also include a substantial amount of continental minerals such as kaolinite and quartz, traces of plants marked by the presence of pollens (Johnson et al., 2000), as well as some remains of terrestrial mammals (Gingerich & Cappetta, 2014), which clearly indicate the close proximity of the coast.

Material and methods

Palaeophiid remains described here were surface-collected as isolated specimens from the BBM horizon in the 1980s by Michel Traverse, former mining engineer at Kpogamé-Hahotoé, during several field campaigns at the north-eastern part of the Kpogamé quarry. Additional specimens were collected by one of us (HC) during fieldwork in 1985. The snake material pertains to different individuals, of various ontogenetic stages. All the Togolese specimens described here are housed in the collections of the University of Montpellier, France (specimen numbers preceded by KPO).

3D reconstructions

The vertebrae were imaged using high-resolution microtomography (μCT) at the MRI platform of the Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de Montpellier (ISE-M). Image segmentation of the vertebral elements was performed on the μCT images with Avizo.Lite 2019.4 (Visualization Sciences Group) software. The 3D virtual restoration was performed with MorphoDig software (v. 1.5.3; Lebrun 2018) and the virtually restored 3D models are deposited in MorphoMuseuM (Georgalis et al., 2021).

Comparisons

For comparative purposes, fossil specimens of palaeophiids (including multiple type specimens) were studied in the collections of MGP-PD, MNHN, NHMUK, NHMW, PIMUZ, and ZPW. Skeletal material of extant snakes was also studied at HNHM, MDHC, MNCN, MNHN, NHMW, ZPW, and ZZSiD.

Anatomical terminology

Terminology of the vertebral anatomy of palaeophiid snakes follows Rage (1983a), Rage et al. (2003), McCartney et al., (2018), and Georgalis et al. (2020).

Systematic palaeontology

Squamata Oppel, 1811

Serpentes Linnaeus, 1758

Palaeophiidae Lydekker, 1888

Genus Palaeophis Owen, 1841

Species Palaeophis africanus Andrews, 1924

Figures 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9

Anterior trunk vertebra UM KPO 22 in anterior (a), posterior (b), dorsal (c), ventral (d), left lateral (e), and right lateral (f) views. Note that the anterior hypapophysis is broken in these photographs, a damage that occurred after the micro-CT scanning of this specimen, where that structure was complete (see Fig. 4a–d)

3D models of anterior and anterior mid-trunk vertebrae: a–d UM KPO 22 in right anterolateral (a), ventral (b), right lateral (c), and left ventrolateral (d) views; e–h UM KPO 33 in left anterolateral (e), ventral (f), posterodorsal (g), and left lateral (h) views; (i–l) UM KPO 25 in left anterolateral (i), posterior (j), right lateral (k), and dorsal (l) views; m–n UM KPO 32 in anterodorsal (m) and dorsal (n) views; (o–p) UM KPO 34 in dorsal (o) and posterior (p) views; (q) UM KPO 37 in ventral view. Specimens not to the same scale

a Anterior trunk vertebra UM KPO 34 in posterior view (a); b–e anterior or anterior mid-trunk vertebra UM KPO 28 in posterior (b), dorsal (c), right lateral (d), and left lateral (e) views; f–k anterior or anterior mid-trunk vertebra UM KPO 23 in anterior (f), posterior (g), dorsal (h), ventral (i), left lateral (j), and right lateral (k) views

3D models of anterior or anterior mid-trunk vertebrae: a–d UM KPO 26 in anterodorsal (a), posterior (b), ventral (c), and right lateral (d) views; e–h UM KPO 28 in right anterolateral (e), posterior (f), ventral (g), and left lateral (h) views; i–k UM KPO 27 in right anterolateral (i) left anterolateral (j), and right ventrolateral (k) views; l–m UM KPO 35 in ventral (l) and posterior (m) views. Specimens not to the same scale

3D models of anterior mid- or mid-trunk vertebrae: a–d UM KPO 30 in anterodorsal (a), posterior (b), left ventrolateral (c), and left lateral (d) views; e–h UM KPO 21 in anterior (e), posterior (f), dorsal (g), and anteroventral (h) views; i–l UM KPO 24 in anterior (i), right posterolateral (j), dorsal (k), and ventral (l) views. Specimens not to the same scale

Material: 51 isolated trunk vertebrae (UM KPO 21–UM KPO 71).

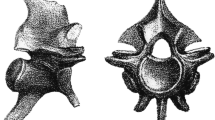

Description: All vertebrae are large and robust (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). They vary in size, with centrum lengths ranging between 19 and 31.5 mm (see Appendix 1). The majority of the available vertebrae pertain to the anterior or anterior mid-trunk portion of the column (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), while few of them can be identified as mid-trunk vertebrae (Figs. 8, 9). There are no posterior trunk vertebrae in our sample. All vertebrae are relatively laterally compressed, with this compression being more prominent in anterior trunk vertebrae.

The neural spine commences almost immediately posterior to the level of the zygosphene, but its anterior edge is still separated from the anterior border of the zygosphene. The height of the neural spine cannot be assessed as it is broken in all specimens. The neural spine is getting thicker in dorsal view towards its posterior portion (i.e., triangular neural spine in cross section). Such thickness in the posterior portion of the neural spine is more pronounced in some specimens (e.g., UM KPO 27). Neural spine foramina are present, with their shape, size, and number not being consistent among the different vertebrae. The neural arch is vaulted. The posterior median notch of the neural arch is not preserved in most specimens—only in UM KPO 35 (and to a lesser degree in UM KPO 26 [Fig. 6c]) it is preserved, being rather deep. Most pterapophyses are damaged; when preserved, they are moderately prominent but they do not extend much dorsally [e.g., UM KPO 26 (Figs. 6a–b, 7b)].

The zygosphene is massive and thick in anterior view. It is usually almost triangular, but its thickness varies. Its dorsal level is usually slightly to moderately convex, with its median portion being elevated dorsally. In some specimens, this dorsal elevation is rather prominent, forming a distinct triangle (e.g., UM KPO 32 [Fig. 4m]). In most cases, the zygosphene is wider than the cotyle, but it can be narrower in some specimens (UM KPO 35). Interestingly, all specimens display a distinctly large and deep pit or fossa at the mid-level surface of the zygosphene in anterior view, which becomes rather deep in certain specimens (e.g., UM KPO 21 [Fig. 9e], UM KPO 23 [Fig. 5f], UM KPO 27 [Fig. 7i–j], UM KPO 31, UM KPO 32 [Fig. 4m], UM KPO 35). This feature is also present in the smallest specimens (e.g., UM KPO 34). In dorsal view, the zygosphene is concave, with two prominent lateral lobes and no median one (e.g., UM KPO 22 [Fig. 2c]; UM KPO 33 [Fig. 3c]). In some specimens, this concavity of the zygosphene in dorsal view is so prominent that it takes the shape of a high-angled V (e.g., UM KPO 22 [Fig. 2c]). Parazygosphenal foramina are absent.

When preserved, the zygantrum is wide and tall. Its walls are relatively thick (e.g., UM KPO 26 [Figs. 6b, 7b], UM KPO 28 [Fig. 7f]), although this thickness significantly decreases in small specimens (e.g., UM KPO 34 [Figs. 4p, 5a]). Intrazygantral foramina are present and can be prominent (e.g., UM KPO 28 [Fig. 5b]). One intrazygantral foramen is usually present right at the centre of the zygantrum, along with two prominent foramina on each zygantral facet (e.g., UM KPO 30 [Fig. 8b]). However, in some specimens this medial foramen is absent (UM KPO 37), while in some others, there is only a single medial foramen in the zygantrum, i.e., there are no foramina inside each zygantral facet (e.g., UM KPO 26 [Figs. 6b, 7b]).

The prezygapophyses extend anterolaterally in dorsal view and anterodorsally in lateral view, and dorsolaterally in anterior view. The prezygapophyseal articular facets are small. There are no prezygapophyseal accessory processes. A prezygapophyseal buttress runs longitudinally from the level of the prezygapophysis and ventrally up to the paradiapophysis, being rather pronounced in certain specimens (e.g., UM KPO 28) including some of the smallest specimens (e.g., UM KPO 34). Postzygapophyses are damaged in most specimens. When preserved, they are always small (e.g., UM KPO 30 [Fig. 8c–d], UM KPO 31). The postzygapophyseal articular facets are small and oval-shaped (e.g., UM KPO 30 [Fig. 8d], UM KPO 31). The interzygapophyseal constriction is rather shallow and becomes almost straight in anterior trunk vertebrae (e.g., UM KPO 22 [Fig. 2c]). The interzygapophyseal ridges are distinct. Most specimens possess a scar-like structure below the level of the interzygapophyseal ridge, which is probably for muscle attachment (e.g., UM KPO 25 [Fig. 4k], UM KPO 30 [Fig. 8e–f]).

The neural canal is usually relatively small, much smaller than the cotyle and condyle, possessing an overall semicircular shape. A distinct ridge is present in some specimens, running throughout a portion of the mid-level of its ventral surface (UM KPO 26 [Figs. 6b, 7a–b], UM KPO 27). Lateral foramina are prominent in some specimens, and multiple of them can be present on each lateral side of the vertebra (e.g., UM KPO 26 [Fig. 7d]; UM KPO 27 [Fig. 7k]).

Cotyle and condyle are situated at an almost horizontal axis. The cotyle displays distinct thick lips and is large, deep, and circular to elliptical in shape. Paracotylar fossae are deep. Paracotylar foramina are present. One paracotylar foramen is visible next to the cotyle in most specimens—it is not possible to tell if these foramina are consistently present on both sides of the cotyle, as the respective areas are usually not fully complete on both sides in most specimens. In some specimens, the paracotylar foramina can be doubled on one side (e.g., UM KPO 21 [Fig. 9e]), or even doubled on both sides of the cotyle (e.g., UM KPO 27 [Fig. 7i–j]). The condyle is large, sometimes massive (e.g., UM KPO 22 [Fig. 2b]; UM KPO 25 [Fig. 4j]; UM KPO 27).

A single large hypapophysis is present in all mid-trunk vertebrae. Instead, in all anterior trunk vertebrae (which form the majority of the available specimens) there are two hypapophyses (e.g., UM KPO 22 [Figs. 2, 4a–d]). The anterior hypapophysis is more prominent in more anterior vertebrae, while it is incipient across the transition between anterior and mid-trunk vertebrae (e.g., UM KPO 26 [Fig. 6]). The shape and full size of the anterior hypapophysis can rarely be evaluated, as it is partially or almost completely damaged in most cases. When preserved, it faces anteroventrally, either more ventrally than anteriorly (e.g., UM KPO 22 [Fig. 4a, c–d]) or either more anteriorly than ventrally (e.g., UM KPO 26 [Figs. 6, 7c–d], UM KPO 33 [Fig. 3, 4e–f, h), being nevertheless always smaller than the posterior hypapophysis. The shape and size of the posterior hypapophysis are variable. When preserved, the posterior hypapophysis can be much ventrally projecting (e.g., UM KPO 23 [Fig. 5j–k], UM KPO 28 [Figs. 5d–e, 7h], UM KPO 31, UM KPO 36); this element can be considerably thick ventrally (e.g., UM KPO 35 [Fig. 7l–m). In specimens showing a robust posterior hypapophysis, a distinct ridge runs throughout its midline, which is clearly visible in ventral, anterior, and posterior views (e.g., UM KPO 31, UM KPO 37 [Fig. 4q]). In some anterior trunk vertebrae, the two hypapophyses are connected by a ridge (e.g., UM KPO 22 [Fig. 4b]); however, this ridge diminishes in height in the transition between anterior mid- and mid-trunk vertebrae, but is still relatively thick and rounded (e.g., UM KPO 24 [Fig. 9l], UM KPO 35 [Fig. 7l]). Subcentral foramina are prominent. Paradiapophyses are damaged or at least highly eroded in almost all specimens. In fact, the left paradiapophysis is only preserved in UM KPO 34 and faces ventrally (Fig. 5a)—it seems that it does not reach the same ventral extent as the posterior hypapophysis, but the full extent of that hypapophysis cannot be estimated with full certainty.

Remarks: The vertebrae described here can be assigned to Palaeophiidae on the basis of their robustness, tallness, and lateral compression, the presence of pterapophyses, the horizontality of the cotyle–condyle axis, the rather large cotyle and condyle, the presence of a second, small hypapophysis in its anterior trunk vertebrae (i.e., anterior hypapophysis, right ventrally to the cotyle), the presence of compressed prezygapophyseal buttresses that form a ridge extending from the dorsal border of the paradiapophyses up to the prezygapophyseal articular facets, the dorsoventrally thick zygosphene, and the presence of large intrazygantral foramina (characters from Georgalis et al., 2020; Houssaye et al., 2013; McCartney et al., 2018; Rage et al., 2003; Rage, 1983a). The material can be further referred to the genus Palaeophis on the basis of its relatively small pterapophyses and the neural spine rising posteriorly from the level of the zygosphenal roof (characters from Houssaye et al., 2013; Parmley & Case, 1988; Parmley & DeVore, 2005; Rage, 1983a; Rage et al., 2003). Indeed, referral to Pterosphenus can be discarded, as the vertebrae from Togo are much broader and possess more laterally directed prezygapophyses and postzygapophyses, prezygapophyses extending more dorsally than the ventral level of the neural canal, and a not so distinctly convex zygosphene (Janensch, 1906; McCartney & Seiffert, 2016; Rage et al., 2003). See “Discussion” below for a justification of the referral of the Togo specimens to Palaeophis africanus and comparison with all other African Palaeophis spp.

Discussion

Considering their highly distinctive features, referral of isolated vertebrae to Palaeophiidae and Palaeophis is relatively straightforward. However, species-level identification of Palaeophis specimens is more problematic, as intraspecific and intracolumnar variations among palaeophiids are still largely unknown, while some anatomical features appear to be more widespread and/or variable than previously conceived. Attempts to decipher intracolumnar variation and diagnostic anatomical traits throughout parts of the palaeophiid vertebral column (e.g., Houssaye et al., 2013; Janensch, 1906; McCartney et al., 2018; Rage, 1983a) or ontogenetic variation (e.g., Parmley & Reed, 2003) have indeed proven useful, but species delimitations often remain vague. Such difficulties can be partially attributed to the fact that the original type material of Palaeophis toliapicus Owen, 1841, the type species of the genus, from the early Eocene of England, has never been adequately redescribed (GLG, in progress). In order to attempt a more precise determination of the Togolese material, we directly examined the holotypes of all three named African Palaeophis species, and a number of additional referred or undescribed specimens from Africa.

As was mentioned above, four different species of palaeophiids have been described from the Eocene of Africa. In addition, the continent has also yielded the most ancient remains of the group (i.e., Cretaceous), which, however, could not be assigned at the species level (Rage & Werner, 1999; Rage & Wouters, 1979). Among the named species, three pertain to Palaeophis (i.e., Palaeophis africanus, Palaeophis maghrebianus, and Palaeophis colossaeus), and one in Pterosphenus (i.e., Pterosphenus schweinfurthi), with the latter being the most adapted to the aquatic realm and characterized by an even more extreme vertebral morphology. Pterosphenus schweinfurthi has been described from the late Eocene of the Fayum, Egypt (Andrews, 1901, 1906; Janensch, 1906; McCartney & Seiffert, 2016) and the middle Eocene of the Idam Unit, Libya (Hoffstetter, 1961), while similar or even conspecific forms have been documented from the middle Eocene of Angola and the middle and late Eocene of Morocco (Pterosphenus cf. schweinfurthi of Antunes, 1964 and Zouhri et al., 2018, 2021). This species was originally placed in its own genus Moeriophis Andrews, 1901, but it was soon subsequently referred to the North American-typified genus Pterosphenus by the same author (Andrews, 1906).

Palaeophis maghrebianus has been described from the early Eocene of the Phosphates of Morocco (Arambourg, 1952; Houssaye et al., 2013) (Fig. 10k–o). Palaeophis colossaeus is known from the early–middle Eocene of the Tamaguélelt Formation, Mali (Houssaye et al., 2019; McCartney et al., 2018; O’Leary et al., 2019; Rage, 1983b) and represents the largest known palaeophiid snake (Fig. 10f–j). Palaeophis africanus was originally described from the middle Eocene of Abeokuta region, Nigeria (Andrews, 1924) (Fig. 10a–e), and was recently reported from the middle Eocene of the Congo Basin, Angola (Folie et al., 2021). Furthermore, two fragmentary vertebrae from the late Eocene of Georgia, USA have been referred to as Pa. africanus (Parmley & DeVore, 2005), extending significantly both its geographic and stratigraphic distributions. However, this occurrence is based on a single published drawing that cannot afford any definite species-level referral. Consequently, it is more reasonable to consider this North American record as Palaeophis cf. africanus, and restrict Pa. africanus to Africa.

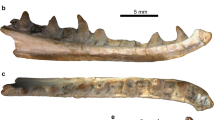

Type specimens of all named African species of Palaeophis: a–e holotype trunk vertebra (NHMUK PV R 4964) of Palaeophis africanus from the middle Eocene of Oshosun Formation, Nigeria, in anterior (a), posterior (b), dorsal (c), ventral (d), and left lateral (e) views; f–j holotype trunk vertebra (MNHN.F. TGE615) of Palaeophis colossaeus from the early–middle Eocene of the Tamaguélelt Formation, Mali, in anterior (f), posterior (g), dorsal (h), ventral (i), and right lateral (j) views; k–o holotype trunk vertebra (MNHN.F. APH5) of Palaeophis maghrebianus from the early Eocene of the phosphates of Djemaïa, Oulad Abdoun, Morocco, in anterior (k), posterior (l), dorsal (m), ventral (n), and left lateral (o) views. From the collections of the Natural History Museum, London and the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris

We consider that all Togolese vertebrae pertain to a single taxon. Differences among the vertebrae with regard to the overall size, the shape and thickness of the zygosphene, the shape and orientation of anterior and posterior hypapophyses, the size of the cotyle and condyle, the lateral extension of the prezygapophyses, the shape and size of the neural canal, the number and size of the intrazygantral foramina, and the vertebral lateral compression can be attributed to intracolumnar variation. Indeed, some of these features are known for snakes to be subjected to a high degree of intracolumnar or intraspecific variation or to ontogenetic variability in snakes (e.g., the thickness of the zygosphene; see Georgalis & Scheyer, 2019).

It appears that the new Togolese material bears more resemblances with Palaeophis africanus. The most significant features shared among the Togolese material with that of the type and previously referred specimens (Fig. 10a–e) of Pa. africanus can be observed in the overall shape, robustness and lateral compression of the vertebrae, the thickness of the zygosphene, the prominence of the interzygapophyseal ridges, the shape of the neural spine and the prezygapophyses, the height of the pterapophyses, the presence of a muscular scar below the level of the interzygapophyseal ridge, and the absence of parazygosphenal foramina.

Furthermore, we can exclude conspecific affinities of the Togolese material from Palaeophis maghrebianus and Palaeophis colossaeus, on the basis of important differences in the vertebral anatomy (Fig. 10f–o). More particularly, the specimens described here can be differentiated from Pa. maghrebianus by their more distinct interzygapophyseal ridges, neural spine commencing more proximately to the level of the zygosphene, and larger ratio of zygosphene width to cotyle width (Fig. 10k–o). The differences are even more apparent with Pa. colossaeus, from which the Togolese specimens can be differentiated by their vertebrae being smaller, less robust and less massive, and more laterally compressed, by lacking parazygosphenal foramina, and possessing more prominent interzygapophyseal ridges, and less massive, less thick, and more convex zygosphene in anterior view (Fig. 10f–j).

Accordingly, we refer the Togo material to Palaeophis africanus. Nevertheless, we have to highlight certain differences with the so far few other known vertebrae of this taxon. The most important difference between the specimens described here and previously published material of Palaeophis africanus lies in the morphology of the zygosphene. In anterior view, the zygosphene of all Togolese vertebrae bears a characteristic deep and large fossa. Such fossa seems to be absent in the Angolan specimens described by Folie et al. (2021). However, a very slight fossa (but of considerably less depth and width), seems to be present in the holotype of the species (NHMUK PV R 4964) (Fig. 10a–e), as well as in another referred (but not figured) specimen (NHMUK PV R 4965(1)) of Andrews (1924); the latter is figured here for the first time (Fig. 11). The potential diagnostic utility of this deep fossa remains difficult to assess in the current state of knowledge and we prefer to attribute these different morphologies to intraspecific variation. Another unusual feature of the Togolese Palaeophis is that the dorsal level of the zygosphene of many specimens is not straight but can instead be relatively convex, in anterior view. This feature has not been reported from other Pa. africanus specimens and is generally rather rare in all Palaeophis species. Such a convexity has been previously documented only at certain anterior trunk vertebrae of Palaeophis maghrebianus from the early Eocene of Morocco and Palaeophis oweni Zigno, 1881, from the middle Eocene of Italy (see Houssaye et al., 2013; Georgalis et al., 2020), and to a lesser degree in Palaeophis typhaeus Owen, 1850, from the middle Eocene of England (Owen, 1850). In fact, the distinctly convex zygosphene is a diagnostic feature of Pterosphenus. However, this convexity is extreme in the latter genus (Janensch, 1906; McCartney & Seiffert, 2016; Rage et al., 2003) and thus differs from the condition observed in the Togolese material. Finally, the shape of the zygosphene in dorsal view is relatively different in comparison with the holotype of Pa. africanus, where this element is not so concave. Nevertheless, a more pronounced concavity is observable in one of the referred vertebrae (NHMUK PV R 4965(1)) of Andrews (1924) from Nigeria (Fig. 11c), as well as in the Angolan specimens described by Folie et al. (2021), though admittedly none of them reach the concavity observed in certain Togo vertebrae.

Referred specimens of Palaeophis africanus from the middle Eocene of Oshosun Formation, Nigeria. a–e Trunk vertebra NHMUK PV R 4965(1) in anterior (a), posterior (b), dorsal (c), right lateral (d), and left lateral (e) views; f–i trunk vertebra NHMUK PV R 4965(2) in anterior (f), posterior (g), ventral (h), and left lateral (i) views. Both these specimens were originally mentioned by Andrews (1924) but had never been figured so far. From the collections of the Natural History Museum, London

Taking into consideration the holotype and previously described specimens of Palaeophis africanus together with the abundant new material from Togo, we attempt to provide a (tentative) diagnosis for this species. Palaeophis africanus can be differentiated from other palaeophiid snakes by the combination of the following features: (i) vertebrae not very massive and slightly laterally compressed; (ii) massive and thick zygosphene; (iii) prominent interzygapophyseal ridges; (iv) neural spine commencing almost immediately after the zygosphene; (v) relatively short pterapophyses; (vi) well-developed prezygapophyses; (vii) presence of a muscular scar below the level of the interzygapophyseal ridge; (viii) presence of two hypapophyses in anterior and anterior mid-trunk vertebrae, and (ix) absence of parazygosphenal foramina. Note that the features in the zygosphenal morphology of the Togo specimens discussed in the paragraph above may eventually have a diagnostic utility as well, however, this cannot yet be determined. For detailed differentiation of Pa. africanus from the other two African species of the genus, Pa. colossaeus and Pa. maghrebianus, see above.

The new Togo specimens, comprising more than 50 vertebrae, represent so far the most abundant known material attributable to Palaeophis africanus. Accordingly, it provides novel insights on the anatomy, diagnostic features and morphological variability of this so far enigmatic palaeophiid snake. Furthermore, the new finds shed new light on the Paleogene squamate fauna of Togo, which is extremely poorly known. In fact, the only so far published squamate specimen from the Paleogene of Togo was a snake specimen described and figured by Stromer (1910: fig. 13), originating from the Paleocene of Tabligbo. This specimen was originally tentatively referred by Stromer (1910) to the North American constrictor Aphelophis Cope, 1873 (misspelled as Aphelopsis), a genus currently considered to be a junior synonym of Calamagras Cope, 1873 (Wallach et al., 2014). However, Stromer’s specimen from Tabligbo, currently probably lost, was recently reinterpreted by Smith and Georgalis (in press) as not being a member of Constrictores but instead pertaining to the aquatic nigerophiid genus Amananulam McCartney et al., 2018. It is thus evident that at least two different snake lineages were present in the Paleogene of Togo and we highly anticipate that future fieldwork will enhance our understanding of the diversity and evolution of Paleogene herpetofaunas of this unexplored area.

Availability of data and materials

All fossil specimens described herein are permanently curated in the collections of the University of Montpellier. All other illustrated specimens are permanently curated at the collections of MNHN and NHMUK. The virtually restored 3D models of 17 vertebrae are deposited in MorphoMuseuM (Georgalis et al., 2021).

Change history

11 October 2021

The citation line has been updated in the PDF version of this publication

References

Andrews, C. W. (1901). Preliminary notes on some recently discovered extinct vertebrates from Egypt. (Part II). Geological Magazine, 8, 436–444.

Andrews, C. W. (1906). A descriptive catalogue of the Tertiary Vertebrata of the Fayûm, Egypt, based on the collection of the Egyptian Government in the Geological Museum, Cairo, and on the collection in the British Museum (Natural History), London (p. 324). London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History).

Andrews, C. W. (1924). Note on some Ophidian vertebræ from Nigeria. Geological Survey of Nigeria, 7, 39–43.

Antunes, M. T. (1964). O neocretacico e o cenozoico do litoral de Angola (pp. 1–255). Lisboa: Junta de Investigaçoes do Ultramar.

Arambourg, C. (1952). Les vertébrés fossiles des gisements de phosphates (Maroc-Algérie-Tunisie). Notes et Mémoires du Service Géologique du Maroc, 92, 1–372.

Berggren, W. A., & Pearson, P. N. (2005). A revised tropical to subtropical Paleogene planktonic foraminiferal zonation. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 35, 279–298.

Bourdon, E., & Cappetta, H. (2012). Pseudo-toothed birds (Aves, Odontopterygiformes) from the Eocene phosphate deposits of Togo, Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32, 965–970.

Cappetta, H., & Traverse, M. (1988). Une riche faune de sélaciens dans le bassin à phosphate de Kpogamé-Hahotoé (Eocène moyen du Togo): Note préliminaire et précisions sur la structure et l’âge du gisement. Geobios, 21, 359–365.

Colonna-Cimera, J. (1961). Note sur le démarrage de l’exploitation du gisement de phosphate du bas-Togo. Rapport de la Direction Générale des Mines et de la Géologie, 1961, 1–12.

Cope, E. D. (1873). Synopsis of new Vertebrata from the Tertiary of Colorado: obtained during the summer of 1873 (p. 19). Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Folie, A., Mees, F., De Putter, T., & Smith, T. (2021). Presence of the large aquatic snake Palaeophis africanus in the middle Eocene marine margin of the Congo Basin, Cabinda, Angola. Geobios, 66–67, 45–54.

Georgalis, G. L., Del Favero, L., & Delfino, M. (2020). Italy’s largest snake: Redescription of Palaeophis oweni from the Eocene of Monte Duello, near Verona. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 65, 523–533.

Georgalis, G. L., Guinot, G., Kassegne, K. E., Amoudji, Y. Z., Johnson, A. K. C., Cappetta, H., & Hautier, L. (2021). 3D data related to the publication: An assemblage of giant aquatic snakes (Serpentes, Palaeophiidae) from the Eocene of Togo. MorphoMuseuM. https://doi.org/10.18563/journal.m3.154

Georgalis, G. L., & Scheyer, T. M. (2019). A new species of Palaeopython (Serpentes) and other extinct squamates from the Eocene of Dielsdorf (Zurich, Switzerland). Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 112, 383–417.

Georgalis, G. L., & Smith, K. T. (2020). Constrictores Oppel, 1811—the available name for the taxonomic group uniting boas and pythons. Vertebrate Zoology, 70, 291–304.

Gingerich, P. D., & Cappetta, H. (2014). A new archaeocete and other marine mammals (Cetacea and Sirenia) from lower middle Eocene phosphate deposits of Togo. Journal of Paleontology, 88, 109–129.

Head, J. J., Holroyd, P. A., Hutchison, J. H., & Ciochon, R. L. (2005). First report of snakes (Serpentes) from the Late Middle Eocene Pondaung Formation, Myanmar. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 25, 246–250.

Hoffstetter, R. (1939). Contribution à l’étude des Elapidæ actuels et fossiles et de l’ostéologie des Ophidiens. Archives du Muséum d’histoire Naturelle de Lyon, 15, 1–78.

Hoffstetter, R. (1958). Un serpent marin du genre Pterosphenus (Pt. sheppardi nov. sp.) dans l’Éocène supérieur de l’Equateur (Amérique du Sud). Bulletin de la Société Geologique de France, 8, 45–50.

Hoffstetter, R. (1960). Présence de Pterosphenus (serpent paléophidé) dans l’Eocène supèrieur du bord occidental du désert libyque. Comptes Rendus Sommaires de la Société Géologique de France, Paris, 1960, 41.

Hoffstetter, R. (1961). Nouvelles récoltes de serpents fossiles dans l’Éocène supérieur de désert Libyque. Bulletin du Muséum National d’histoire Naturelle Paris (série 2), 33, 326–331.

Houssaye, A., Herrel, A., Boistel, R., & Rage, J.-C. (2019). Adaptation of the vertebral inner structure to an aquatic life in snakes: Pachyophiid peculiarities in comparison to extant and extinct forms. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 18, 783–799.

Houssaye, A., Rage, J.-C., Bardet, N., Vincent, P., Amaghzaz, M., & Meslouh, S. (2013). New highlights about the enigmatic marine snake Palaeophis maghrebianus (Palaeophiidae; Palaeophiinae) from the Ypresian (Lower Eocene) phosphates of Morocco. Palaeontology, 56, 647–661.

Hutchison, J. H. (1985). Pterosphenus cf. P. schucherti Lucas (Squamata, Palaeophidae) from the Late Eocene of Peninsular Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 5, 20–23.

Janensch, W. (1906). Pterosphenus schweinfurthi Andrews und die Entwicklung der Palaeophiden. Archiv für Biontologie, 1, 307–350.

Johnson, A. K. C. (1987). Le Bassin côtier à phosphate du Togo (Maastrichtien-Eocène moyen) (p. 365). Universités de Bourgogne (France) et du Bénin (Togo).

Johnson, A. K. C., Rat, P., & Lang, J. (2000). Le bassin sédimentaire à phosphate du Togo (Maastrichtien-Eocene): Stratigraphie, environnements et évolution. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 30, 183–200.

Kassegne, K. E., Mourlam, M. J., Guinot, G., Amoudji, Y. Z., Martin, J. E., Togbe, K. A., Johnson, A. K., & Hautier, L. (2021). First partial cranium of Togocetus from Kpogamé (Togo) and the protocetid diversity in the Togolese phosphate basin. Annales de Paléontologie, 107, 102488.

Lebrun, R. (2018). MorphoDig, an open-source 3d freeware dedicated to biology. In: IPC5 The 5th International Palaeontological Congress, Paris, France.

Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (p. 824). Stockholm: Laurentii Salvii.

Lucas, F. A. (1898). A new snake from the Eocene of Alabama. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 21, 637–638.

Lydekker, R. (1888). Notes on Tertiary Lacertilia and Ophidia. Geological Magazine, 5, 110–113.

Massalongo, A. (1859). Specimen photographicum animalium quorumdam plantarumque fossilium agri Veronensis (p. 101). Veronae (= Verona): Vicentinius et Fran chinius Excudebant.

McCartney, J. A., & Seiffert, E. R. (2016). A late Eocene snake fauna from the Fayum Depression, Egypt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 36, e1029580.

McCartney, J. A., Roberts, E. M., Tapanila, L., & O’Leary, M. A. (2018). Large palaeophiid and nigerophiid snakes from Paleogene Trans-Saharan Seaway deposits of Mali. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 63, 207–220.

Nopcsa, F. (1923a). Die familien der reptilien. Fortschritte der Geologie und Paläontologie, 2, 1–210.

Nopcsa, F. (1923b). Eidolosaurus und Pachyophis Zwei Neue Neocom-Reptilien. Palaeontographica, 65, 99–154.

O’Leary, M., Bouaré, M. L., Claeson, K. M., Hill, R. V., McCartney, J., Sessa, J. A., Sissoko, F., Tapanila, L., Wheeler, E., & Roberts, E. M. (2019). Stratigraphy and paleobiology of the Upper Cretaceous-Lower Paleogene sediments from the trans-Saharan seaway in Mali. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 436, 1–177.

Oppel, M. (1811). Die Ordnungen, Familien und Gattungen der Reptilien als Prodrom einer Naturgeschichte derselben (p. 87). Munich: Joseph Lindauer.

Owen, R. (1841). Description of some ophidiolites (Palæophis toliapicus) from the London Clay of Sheppey, indicating an extinct species of serpent. Transaction of the Geological Society Second Series, 6, 209–210.

Owen, R. (1850). Part III. Ophidia (Palæophis & c.). In R. Owen (Ed.), Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the London Clay and of the Bracklesham and other Tertiary beds (pp. 51–63). London: Palæontographical Society of London.

Parmley, D., & Case, G. R. (1988). Palaeopheid snakes from the gulf coastal region of North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 8, 334–339.

Parmley, D., & DeVore, M. (2005). Palaeopheid snakes from the Late Eocene Hardie Mine local fauna of central Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist, 4, 703–722.

Parmley, D., & Reed, H. W. (2003). Size and age class estimates of North American Eocene palaeopheid snakes. Georgia Journal of Science, 61, 220–232.

Rage, J. C. (1983a). Les serpents aquatiques de l’Éocène européen. Définition des espèces et aspects stratigraphiques. Bulletin du Muséum National d’histoire Naturelle, Section C, Sciences de la Terre, Paléontologie, Géologie, Minéralogie, 4(5), 213–241.

Rage, J. C. (1983b). Palaeophis colossaeus nov. sp. (le plus grand Serpent connu?) de l’Eocène du Mali et le problème du genre chez les Palaeopheinae. Comptes Rendus de l’académie des Sciences, Série, 2(296), 1741–1744.

Rage, J.-C., Bajpai, S., Thewissen, J. G. M., & Tiwari, B. N. (2003). Early Eocene snakes from Kutch, Western India, with a review of the Palaeophiidae. Geodiversitas, 25, 695–716.

Rage, J.-C., & Werner, C. (1999). Mid-Cretaceous (Cenomanian) snakes from Wadi Abu Hashim, Sudan: The earliest snake assemblage. Palaeontologia Africana, 35, 85–110.

Rage, J.-C., & Wouters, G. (1979). Decouverte du plus ancien Palaeopheide (Reptilia, Serpentes) dans le Maestrichtien du Maroc. Geobios, 12, 293–296.

de Rochebrune, A. T. (1880). Revision des ophidiens fossiles du Museum d’Histoire Naturelle. Nouvelles Archives du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle 2ème Série, 3, 271–296.

Slansky, M. (1962). Contribution à l’étude géologique du bassin sédimentaire côtier du Dahomey et du Togo (p. 335). Thèse université de Nancy.

Smith, K. T., & Georgalis, G. L. (In press). The diversity and distribution of Palaeogene snakes: a review, with comments on vertebral sufficiency. In: D. Gower, & H. Zaher (Eds.), The origin and early evolution of snakes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stromer, E. (1910). Reptilien- und Fischreste aus dem marinen Alttertiär Südtogo (Westafrika). Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Geselschaft, 62, 478–507.

Vandenberghe, N., Speijer, R., & Hilgen, F. J. (2012). The Paleogene period (pp. 855–921). In: F. M. Gradstein, J. G. Ogg, M. Schmitz, & G. M. Ogg (Eds.), The geological time scale 2012. Elsevier Science.

Visse, L. (1957). Le faciès phosphate togolais. Rapport inédit (p. 119). Direction Générale des Mines et de la Géologie.

Wallach, V., Williams, K. L., & Boundy, J. (2014). Snakes of the world: A catalogue of living and extinct species (p. 1237). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

de Zigno, A. (1881). Nuove aggiunte alla fauna eocena del Veneto. Memorie del Reale Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 21, 775–790.

Zouhri, S., Gingerich, P., Khalloufi, B., Bourdon, E., Adnet, S., Jouve, S., Elboudali, N., Amane, A., Rage, J.-C., Tabuce, R., & de Broin, F.L. (2021). Middle Eocene vertebrate fauna from the Aridal Formation, Sabkha of Gueran, southwestern Morocco. In: J.-S. Steyer, M. L. Augé, & G. Métais (Eds.), Memorial Jean-Claude Rage: A life of paleo-herpetologist. Geodiversitas, 43, 121–150.

Zouhri, S., Khalloufi, B., Bourdon, E., de Broin, F. L., Rage, J.-C., M’Haïdrat, L., Gingerich, P. D., & Elboudali, N. (2018). Marine vertebrate fauna from the late Eocene Samlat Formation of Ad-Dakhla, south western Morocco. Geological Magazine, 155, 1596–1620.

Zvonok, E. A., & Snetkov, P. B. (2012). New findings of snakes of the genus Palaeophis Owen, 1841 (Acrochordoidea: Palaeophiidae) from the middle Eocene of Crimea. Proceedings of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 316, 392–400.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nour-Eddine Jalil (MNHN) and Mike Day (NHMUK) for access and permission to use photographs of specimens under their care. We also thank Massimo Delfino (MDHC), Letizia Del Favero (MGP-PD), Zbigniew Szyndlar (ZZSiD), and Bartosz Borczyk (UWr) for access to comparative material under their care. We are grateful to Mehdi Mouana (UM) for help with photographing of the material, Annelise Folie (Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences) for help with the literature, and Torsten Scheyer (PIMUZ) for useful comments on the 3D visualization. The quality of the manuscript was enhanced by the useful comments provided by the editors Daniel Marty and Graciela Piñeiro and the two reviewers, Adriana Albino and an anonymous one.

Funding

GLG acknowledges funding from Forschungskredit of the University of Zurich, grant no. [FK-20–110]. 3D data acquisition was performed using the μCT facilities of the MRI platform member of the national infrastructure France-Bio Imaging supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-10-INBS-04, ‘Investments for the future’) and of the Labex CEMEB (ANR-10-LABX-0004) and NUMEV (ANR-10-LABX-0020). Study of other Palaeophis specimens and comparative material was made possible through the grants SYNTHESYS GB-TAF-6591 (NHMUK), SYNTHESYS ES-TAF-5910 (MNCN), SYNTHESYS AT-TAF-5911 (NHMW), and SYNTHESYS HU-TAF-6145 (HNHM) to GLG, and the respective curators (Sandra Chapman, Marta Calvo-Revuelta, Silke Schweiger, and Judit Vörös) are highly thanked here. This study is part of the PaleonTogo project, which is partly supported by a CNRS PICS grant (n8229424) and the National Geographic Society (grant NGS-72222R-20).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LH, GG, and GLG conceived the study; GLG analyzed the data and prepared the figures; LH CT-scanned the specimens and performed the 3D models; GLG, GG, and LH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Editorial handling: Graciela Piñeiro.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: Centrum lengths (CL) of all vertebrae from Kpogamé

Appendix 1: Centrum lengths (CL) of all vertebrae from Kpogamé

Specimen | Centrum length (in mm) |

|---|---|

UM KPO 21 | 30 |

UM KPO 22 | 31 |

UM KPO 23 | 26 |

UM KPO 24 | 24 |

UM KPO 25 | 28.5 |

UM KPO 26 | 25.5 |

UM KPO 27 | 28.5 |

UM KPO 28 | 27 |

UM KPO 29 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 30 | 31 |

UM KPO 31 | 30 |

UM KPO 32 | 29.5 |

UM KPO 33 | 30 |

UM KPO 34 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 35 | 27.5 |

UM KPO 36 | 27.5 |

UM KPO 37 | 23 |

UM KPO 38 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 39 | 31.5 |

UM KPO 40 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 41 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 42 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 43 | 24 |

UM KPO 44 | 26 |

UM KPO 45 | 26 |

UM KPO 46 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 47 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 48 | 21 |

UM KPO 49 | 28.5 |

UM KPO 50 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 51 | 30 |

UM KPO 52 | 29.5 |

UM KPO 53 | 20.5 |

UM KPO 54 | 19 |

UM KPO 55 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 56 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 57 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 58 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 59 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 60 | 29 |

UM KPO 61 | 28 |

UM KPO 62 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 63 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 64 | 24 |

UM KPO 65 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 66 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 67 | 19.5 |

UM KPO 68 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 69 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 70 | Damaged—not available |

UM KPO 71 | Damaged—not available |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Georgalis, G.L., Guinot, G., Kassegne, K.E. et al. An assemblage of giant aquatic snakes (Serpentes, Palaeophiidae) from the Eocene of Togo. Swiss J Palaeontol 140, 20 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-021-00236-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-021-00236-w