Abstract

Background

Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 have a high incidence of thrombosis that decreases after recovery. When coronavirus disease 2019 is accompanied by diseases prone to thrombosis, risk of post-infection thrombotic events may increase.

Case presentation

We report a case of digital ischemic gangrene in a 24-year-old Chinese female with systemic lupus erythematosus after recovery from coronavirus disease 2019. The pathogenesis was related to clinical characteristics of systemic lupus erythematosus, hypercoagulability caused by coronavirus disease 2019, and second-hit due to viral infection.

Conclusion

Patients with autoimmune diseases should remain alert to autoimmune system disorders induced by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and other viruses. Treatment for these patients should be strictly standardized, and appropriate anticoagulation methods should be selected to prevent thrombosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has a high thrombosis rate, although digital ischemic necrosis is relatively rare and mostly occurs in critically ill patients [1]. The incidence of thrombosis in patients after recovery from viral infection is only 2.5% [2]. This report describes a case of a young female patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who suffered from digital ischemic gangrene after recovering from COVID-19.

Clinical presentation

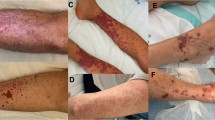

A 24-year-old Chinese female patient experienced gradual cyanosis in the hands and feet after recovering from COVID-19 4 months earlier. The end of the right little finger, the second toe of the right foot, and the third toe of the left foot presented with necrosis and were painful and numb. Erythema of the extremities was also present. The temperature of both hands and feet was low and the patient had cyanotic fingertips and black toes (Fig. 1). However, the bilateral radial, ulnar, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis arteries were pulsating well.

The patient was diagnosed with SLE and lupus nephritis 4 years prior and was treated with prednisone, cyclosporine, hydroxychloroquine, thalidomide, and benazepril. The patient voluntarily stopped using prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, cyclosporine, and thalidomide as symptoms improved 2 years earlier. Before the viral infection, the patient did not have any complaints.

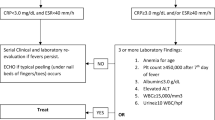

The patient’s blood routine examination, liver and kidney function, and coagulation function showed no significant abnormalities. Routine blood test and coagulation function are presented in Table 1. Other abnormal laboratory tests are presented in Table 2. The patient’s SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) score was 16, indicating severe activity. The photoplethysmography measurement of finger artery perfusion showed a decrease in all finger artery amplitudes, with the waveform appearing as a nearly horizontal straight line indicating peripheral circulatory disorders (Fig. 1).

The patient was diagnosed with SLE, lupus nephritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and arterial thromboembolism.

Hydroxychloroquine, prednisone acetate, and mycophenolate mofetil were chosen to control the patient’s condition. Low-molecular-weight heparin was also administered, while sarpogrelate, kallidinogenase, nifedipine, papaverine, and beraprost sodium were given to improve microcirculation. The patient’s condition improved, with reduced cyanosis, improved limb circulation, and increased skin temperature. On a recent telephone follow-up, there was no further progress in the patient’s limb ischemia.

Discussion

Endothelial injury, inflammation, and hypercoagulability are common clinical features of SLE [3]. Lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein 1, and other autoantibodies are related to arterial and venous thrombosis. However, they increase the risk of thrombosis only under specific conditions, such as platelet activation [4]. Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 can exhibit a series of coagulation abnormalities, such as thrombocytopenia, which serve as a prerequisite for thrombosis in patients with SLE [5]. At the same time, SARS-CoV-2 infection can induce autoimmune abnormalities and even trigger autoimmune diseases [6]. Therefore, viral infection can increase risk of lupus disease activity in patients with SLE, inducing vasculitis caused by strong SLE activity [4, 7]. Notably, the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor increases in patients with SLE, providing more binding sites for SARS-CoV-2 [8]. The interaction between SLE and COVID-19 results in ischemic gangrene even in digital extremities with abundant blood circulation.

In addition to SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe SLE activity in patients is also related to their premature discontinuation of medication use. Hydroxychloroquinone is essential for the treatment of SLE, as it enhances the efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of lupus nephritis and has certain anti-thrombotic effects [9]. Aspirin and hydroxychloroquine are the primary preventive measures for patients with positive antiphospholipid antibodies, and long-term use of warfarin is necessary if the patient has experienced a thrombotic event [9].

For patients with SLE, it is also important to be vigilant about other viral infections since many viruses are related to SLE pathogenesis, especially Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, retroviruses, and cytomegalovirus [10]. There is also a significant correlation between seasonal influenza infection and SLE seizures [10]. There is significant peptide overlap among five common human viruses (influenza A, Borna disease, measles, mumps, and rubella) and human proteome [10]. Sequence similarity leads to an autoimmune response after viral infection, which can promote SLE activity and lead to adverse consequences.

Conclusion

Although the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, autoimmune diseases either induced or exacerbated by SARS CoV-2 and other viruses should be alerted. Treatment for patients with SLE after infection with COVID-19 or other viruses should be strictly standardized and appropriate anticoagulation methods should be selected to prevent thrombosis.

Availability of data

Data of the patient can be requested from the authors.

References

GeorgeGalyfos ASMF. Acute limb ischemia among patients with COVID-19 infection. J Vasc Surg. 2022;1(75):329–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2021.07.222.

Patell R, Bogue T, Koshy A, Bindal P, Merrill M, Aird WC, Bauer KA, Zwicker JI. The long haul COVID-19 arterial thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2020;217:73–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2022.07.008.

Marianthi Kiriakidou CLC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 2020;11(172):C81–96. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC202006020.

Tektonidou MG, Laskari K, Panagiotakos DB, Moutsopoulos HM. Risk factors for thrombosis and primary thrombosis prevention in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthrit Care Res. 2009;61(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24232.

Ulanowska M, Olas B. Modulation of hemostasis in COVID-19; blood platelets may be important pieces in the COVID-19 puzzle. Pathogens. 2021;10(3):370. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10030370.

Bonometti MC. The first case of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) triggered by COVID-19 infection. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;18(24):9695–7. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202009_23060.

Romero-Díaz J, García-Sosa I, Sánchez-Guerrero J. Thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases of recent onset. J Rheumatol. 2009;1(36):68–75. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.071244.

Fu X, Qian Y, Jin X, Yu H, Du L, Wu H, Chen H, Shi Y. COVID-19 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Lupus. 2022;31(6):684–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/09612033221093502.

Durcan L, O’Dwyer T, Petri M. Management strategies and future directions for systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Lancet. 2019;393(10188):2332–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30237-5.

Quaglia M, Merlotti G, De Andrea M, Borgogna C, Cantaluppi V. Viral infections and systemic lupus erythematosus: new players in an old story. Viruses. 2021;13(2):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13020277.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH-W, K-Z and HL-R designed the study, collected data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, JH., Zheng, K., Ren, HL. et al. Digital ischemic necrosis in a patient with systematic lupus erythematosus patient after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a case report. J Med Case Reports 18, 295 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04567-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04567-3