Abstract

Background

Within the spectrum of melanocytic-differentiated tumors, the challenge faced by pathologists is discerning accurate diagnoses, with clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues standing out as a rare and aggressive neoplasm originating from the neural crest. Accounting for 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas, clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues poses diagnostic complexities, often misidentified owing to its phenotypic resemblance to malignant melanoma. This chapter delves into the intricacies of clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues, its epidemiology, characteristic manifestations, and the imperative need for a comprehensive diagnostic approach involving immunohistochemical and molecular analyses.

Case presentation

A compelling case unfolds as a 25-year-old male from Morocco, initially misdiagnosed with malignant melanoma, experiences tumor recurrence on the second toe. With no history of trauma or familial neoplasia, the patient’s clinical journey is explored, emphasizing the importance of detailed clinical examinations and radiological assessments. The chapter elucidates the histopathological findings, immunohistochemical spectrum, and the correlation between clinical parameters and diagnostic inference, ultimately leading to metatarsal amputation. This clinical vignette highlights the multidimensional diagnostic process in soft tissue neoplasms, emphasizing the synergistic role of clinical, radiological, and histopathological insights.

Conclusion

The diagnostic challenges inherent in melanocytic-differentiated tumors, exemplified by the rarity of soft tissue clear cell sarcoma, underscore the essential role of an integrated diagnostic approach. This concluding chapter emphasizes the perpetual collaboration required across pathology, clinical medicine, and radiology for nuanced diagnostic precision and tailored therapeutic strategies. The rarity of these soft tissue malignancies necessitates ongoing interdisciplinary engagement, ensuring the optimization of prognosis and treatment modalities through a comprehensive understanding of the diagnostic intricacies presented by clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of encountering a melanocytic differentiated tumor, pathologists are confronted with the imperative task of discerning potential diagnoses, with clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST) being among the considerations related to diagnostic differentials. This exceedingly rare and aggressive soft tissue neoplasm originates from the neural crest [1] and comprises approximately 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas [1, 2]. Predominantly afflicting young adults and infrequently children, CCSST shares phenotypic characteristics with malignant melanoma, necessitating an investigative approach involving immunohistochemical complementation and molecular biology for precise diagnostic elucidation. Manifesting in diverse anatomical locations, CCSST predominantly manifests in the distal extremities, with its characterization first expounded by Enzinger et al. in 1965 [3]. Primarily involving the fascia and tendons, the malignancy’s protracted progression often culminates in delayed diagnosis, frequently at an advanced metastatic stage. Therapeutic management primarily revolves around meticulous carcinological tumor resection. This study presents an illustrative case of a 25-year-old male presenting with a tumor recurrence of CCSST initially misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. The overarching objective is to underscore the intricacies within the diagnostic spectrum of melanocytic differentiated tumors, emphasizing the consideration of atypical differentials, particularly in young individuals presenting with soft tissue neoplasms devoid of primary cutaneous involvement.

Case presentation

In this intriguing case study, we present the clinical scenario of a 25-year-old Moroccan man with no pertinent prior medical history who presented 2 years ago with a mass on his second toe. Initially, the lesion raised concerns of malignant melanoma owing to its varying pigmentation ranging from dark brown to black. Gross examination revealed irregular borders, asymmetry, and a raised surface with multiple nodules, along with evidence of ulceration. Following an initial biopsy, the lesion was indeed diagnosed as malignant melanoma. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the initial misdiagnosis of malignant melanoma was likely attributable to two factors. Firstly, limitations in the biopsy analysis potentially resulted in the exclusion of the epidermis owing to artifacting. This exclusion inadvertently obscured the crucial anatomical distinction between clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue and melanoma. Secondly, the absence of immunohistochemical analysis, a vital tool for differentiating these entities, further hampered an accurate diagnosis. Following the initial diagnosis, the patient failed to adhere to the established follow-up schedule.

At 18 months later, the lesion recurred, prompting the patient to seek reevaluation at the orthopedic surgery department. Upon physical examination, a painless ulcerated tumor measuring 3 cm in diameter was observed on the right second toe. Notably, the tumor displayed fibrin and pigmented areas on its surface. Surrounding the primary tumor, several erythematous nodular lesions with a firm texture and fixed appearance were noted.

Radiological assessment using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a notable abnormality was observed in the form of a lesion resembling a giant cell tumor affecting the tendon sheaths, as depicted in Fig. 1. This imaging revealed a significant loss of tissue in the first and second phalanx, alongside a simultaneous filling of the first and second interphalangeal gaps, providing a detailed view of the tumor’s impact on the surrounding anatomy. However, despite these findings, the exact nature of the lesion remained uncertain. Potential diagnoses that were considered included giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (GCT-TS), tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT), pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), synovial sarcoma, and the possibility of metastatic disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of the tumor process. A. T1-weighted axial image shows the tumor without contrast enhancement, providing detailed information about its internal structure. B. T1-weighted sagittal image following the administration of gadolinium contrast, it demonstrates a loss of signal intensity from the majority of the first and second phalanges, along with filling of the first and second interphalangeal joints. C. T2-weighted axial image. D. T2-weighted sagittal image. These finding offers a comprehensive visualization of the tumor’s impact on the surrounding anatomy

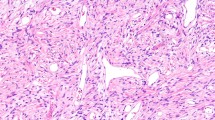

Subsequent excision of a nodular tumor formation, measuring 3.5 × 3 × 1.5 cm, revealed a neoplasm with firm consistency on section. Macroscopically, the lobulated and grayish skin displayed hemorrhagic foci. Microscopic examination, as depicted in Fig. 2, unveiled a tumor proliferation infiltrating the tendon, arranged in lobules demarcated by fibrous septa. The tumor cells, frequently epithelioid in appearance, exhibited small dimensions, ovoid irregularly outlined nuclei with nucleolar prominence, and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with occasional clearing. The stroma exhibited fibroinflammatory characteristics and is devoid of epidermal involvement. Additionally, vascular emboli or necrotic foci were not observed.

Immunohistochemical analysis with antibodies against Melan-A, PS100, HMB-45, and SOX9 was performed on tissue sections (Fig. 3). All four markers demonstrated positive staining within the tumor cells.

Tumor immunohistochemical profile. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated widespread and atypical cytoplasmic expression of HMB-45 and PS100 within tumor cells. Notably, Melan-A and SOX9 exhibited distinct staining patterns. While Melan-A showed focal cytoplasmic expression, SOX9 displayed unique nuclear extension in addition to cytoplasmic positivity. These findings offer a comprehensive characterization of the tumor’s immunophenotypic profile

A panel of IHC markers, including cytokeratin (CK; AE1–AE3 and CK19), FLI1, INI1, desmin, and smooth muscle actin (SMA), was employed to evaluate the origin and characteristics of the soft tissue tumor. The absence of expression in most markers, except for persistent expression of INI1 that provided valuable information in ruling out rhabdoid tumor as a potential diagnosis.

While fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for the t(12;22) (q13;q12) reciprocal translocation could further strengthen the diagnosis, its unavailability in our clinical setting did not impede the formulation of an accurate conclusion.

On the basis of the aforementioned clinical presentation, imaging findings, and particularly the immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, a definitive diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue was established, effectively differentiating it from malignant melanoma.

Importantly, both physical examination and meticulous imaging studies did not reveal any evidence of metastatic spread. The tumor has been categorized as IA on the basis of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 2018 staging.

The patient subsequently underwent metatarsal amputation for definitive treatment. At the 12-month follow-up after metatarsal amputation, the patient remains disease-free with no signs of recurrent or metastatic disease, indicating a favorable clinical course (Table 1).

Discussion

Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST) is a malignant mesenchymal neoplasm primarily affecting deep soft tissues, characterized by a distinctive nested growth pattern and melanocytic differentiation. Diagnostic challenges arise owing to morphological similarities with malignant melanoma, historically leading to its classification as malignant soft tissue melanoma. Advances in molecular biology, particularly the identification of the t(12;22) (q13;q12) translocation and the resultant chimeric EWSR1/ATF1 gene fusion, have significantly enhanced diagnostic precision [4]. Although CCSST typically presents in the third and fourth decades, sporadic occurrences in the pediatric population have been documented [5].

Clinically, CCSST manifests in the lower limbs, particularly the ankle or foot of young adults, often involving tendons or fascia. Uncommon cases have been reported in the neck, gastrointestinal tract, penis, and pleural cavity [6,7,8,9,10].

The accurate diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST) can be challenging owing to its clinical and morphological overlap with several other tumors, especially in the vicinity of tendons and aponeuroses in the extremities. Careful consideration of clinical presentation, microscopic features, and advanced techniques, such as immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), is essential for distinguishing CCSST from its mimics and ensuring optimal patient management.

Histologically, CCSST presents as a well-limited, lobulated, or multinodular tumor with dimensions ranging from 1 to 10 cm, featuring a greyish-white appearance. Characterized by monomorphic cells with a clear or slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and basophilic, oval, vesicular nuclei, CCSST is identifiable by the presence of multinucleated tumor giant cells in about 50% of cases. Glycogen accumulation, highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and PAS with diastase (PAS-D) stains, imparts the characteristic clear appearance of the cells [2]. Immunohistochemistry further reveals positivity for antigens, such as HMB-45, PS100, CD99, Melan-A, NSE, and vimentin [2, 11].

Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST) presents a diagnostic challenge as it can closely resemble malignant melanoma (MM), resulting in diagnostic complexities. Both malignancies exhibit morphological and immunohistochemical similarities, contributing to diagnostic confusion. Traditionally, pathologists adopt a comprehensive approach encompassing various factors, including microscopic features:

Microscopic examination reveals distinctive characteristics of CCSST, typically situated deeper within the dermis, characterized by a uniform distribution of spindle cells surrounded by delicate fibrous tissue. In contrast, MM frequently originates in the epidermis, the outer layer of the skin, displaying notable nucleoli, increased mitotic activity, and migration of atypical melanocytes.

Despite the clear morphological distinctions between clear cell sarcoma and malignant melanoma, both malignancies may present overlapping immunohistochemical profiles. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrates that CCSST expresses markers typically associated with melanocytes, including HMB-45, MiTF, S100, and Melan-A [2].

Thus, relying solely on immunohistochemistry may be insufficient to distinguish between clear cell sarcoma and melanoma owing to their shared expression of melanocytic markers, complicating the diagnostic process. This underscores the importance of thorough clinical correlation. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST) typically affects individuals in the younger to middle-aged adult range and often presents with tumors localized in the extremities, while melanoma is more commonly observed in elderly individuals, often manifesting as pigmented lesions on sun-exposed skin areas. The clinical correlation can aid in guiding diagnostic considerations. Additionally, molecular investigations are essential for achieving an accurate diagnosis.

Through molecular methodologies, clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST) is distinctly identified by a recurring chromosomal aberration, namely the t(12;22) translocation, resulting in the fusion of the EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1) gene with the ATF1 transcription factor gene. This specific rearrangement of the EWSR1/ATF1 genes serves as a defining genetic feature of CCSST, setting it apart from malignant melanoma, where such rearrangement is notably absent. Additionally, techniques, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) play a pivotal role in differentiating synovial sarcoma from CCSST by detecting characteristic translocations or fusion transcripts, such as the t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2) translocation or SYT/SSX fusion transcripts, respectively [2].

Other differential diagnoses include paraganglioma-like dermal melanocytic tumor (PLDM), clear cell myomelanocytic tumor (CCMT), and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), each possessing unique clinical and morphological features aiding in their differentiation from CCSST [2].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) features of CCSST often exhibit benign characteristics, displaying modestly enhanced signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging compared with muscle [12]. Early and accurate diagnosis is paramount, as surgical excision remains the primary curative treatment. Optimal preoperative imaging, facilitated by MRI, aids surgical planning, minimizing perioperative morbidity by outlining the tumor’s relationships with adjacent tissues, including nerves and major arteries [13]. Surgical excision is presently the primary therapeutic approach for early-stage clear cell sarcoma [14,15,16]. Despite its application in palliative care, chemotherapy is recommended for individuals with metastatic disease, although its efficacy remains uncertain [15, 17]. Notably, radiation therapy has demonstrated the capacity to reduce the dimensions of these tumors [15, 18]. Targeted therapies, such as receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors, have shown promising results in some cases; however, most of these interventions have only been explored within the context of clinical trials [19].

A comprehensive analysis of the reported cases (n = 27), including our own case as shown in Table 2, revealed several key findings regarding clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST). The average patient age was 31.15 ± 14.33 years, and females comprised a substantial majority (70%) of the patient population. Notably, the extremities emerged as the most common site of tumor presentation, highlighting the anatomical predilection of CCSST.

Delving into the immunohistochemical profile, S100 protein positivity was observed in a significant proportion of cases (25 out of 27, representing 92.95%). HMB-45 positivity was found in 20 patients (74.07%), while Melan-A expression was present in 15 cases (55.56%). These findings underscore the valuable role of immunohistochemical markers in identifying CCSST.

Furthermore, the EWS/ATF-1 fusion transcript, a characteristic genetic alteration, was detected in 23 patients. Interestingly, only one case exhibited the EWSR/CREB1 rearrangement, highlighting the predominance of the EWS/ATF-1 fusion in this specific sarcoma subtype. These observations contribute to a deeper understanding of the underlying molecular landscape of CCSST.

Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue is characterized by a grim prognosis, primarily attributed to its early propensity for dissemination and a high recurrence rate [14, 20]. Prognostic variables including necrosis, mitotic activity, resection margin, anatomical location, and tumor size exhibit negative correlations with poor prognosis [21]. Among these, tumor size at the time of surgery emerges as a pivotal determinant, displaying the strongest correlation with overall survival [22].

Conclusion

Achieving a definitive differential diagnosis between malignant melanoma and clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues (CCSST) necessitates a comprehensive diagnostic approach. Despite the presence of overlapping morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics, meticulous histopathological evaluation remains imperative prior to resorting to molecular techniques. Additionally, contextual clinical factors, such as younger patient age and involvement of the extremities, serve to bolster the diagnostic inference for CCSST. Given the rarity of CCSST, accurate diagnostic determination heavily relies on collaborative efforts among clinicians, radiologists, and pathologists. This collaborative endeavor is indispensable in ensuring optimal patient outcomes through the facilitation of appropriate treatment modalities tailored to these uncommon neoplasms.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the current study is available from the corresponding author upon motivated request.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- ATF1:

-

Activating transcription factor 1

- CK:

-

Cytokeratin

- CCMT:

-

Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor

- CCSST:

-

Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues

- CREB1:

-

CAMP-response element binding protein

- EWSR1:

-

Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- FLI1:

-

Friend leukemia integration 1

- GCT-TS:

-

Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath

- HMB45:

-

Human melanoma black 45

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- MiTF:

-

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

- MM:

-

Malignant melanoma

- MPNST:

-

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NSE:

-

Neuron specific enolase

- PAS:

-

Periodic acid Schiff

- PLDM:

-

Paraganglioma-like dermal melanocytic tumor

- PVNS:

-

Pigmented villonodular synovitis

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SMA:

-

Smooth muscle actin

- TGCT:

-

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor

References

Malchau SS, Hayden J, Hornicek F, Mankin HJ. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(6):519–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.20730.

Dim DC, Cooley LD, Miranda RN. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(1):152–6. https://doi.org/10.5858/2007-131-152-CCSOTA.

Meis-Kindblom JM. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a historical perspective and tribute to the man behind the entity. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13(6):286–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pap.0000213052.92435.1f.

Bridge JA, Borek DA, Neff JR, Huntrakoon M. Chromosomal abnormalities in clear cell sarcoma. Implications for histogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93(1):26–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/93.1.26.

Pinkerton CR, Philip T. Clear cell sarcoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;16(6):495–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/088800199276769.

Abdellah A, Soufiane B, Amine B, El Sanaa M, Hanan E, Ijlal K, Rachida L, El Basma K, Tayeb K, Noureddine B. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses of the parapharyngeal space: an unusual localization of a rare tumor (a case report and review of the literature). Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19:147. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.19.147.5364.

Covinsky M, Gong S, Rajaram V, Perry A, Pfeifer J. EWS-ATF1 fusion transcripts in gastrointestinal tumors previously diagnosed as malignant melanoma. Hum Pathol. 2005;36(1):74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2004.10.015.

Ito T, Melamed J, Perle MA, Alukal J. Clear cell sarcoma of the penis: a case report. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2015;3(1):43–7.

Chen YT, Yang Z, Li H, Ni CH. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue in pleural cavity: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(19):3126–31. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3126.

Saw D, Tse CH, Chan J, Watt CY, Ng CS, Poon YF. Clear cell sarcoma of the penis. Hum Pathol. 1986;17(4):423–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80468-3.

Hocar O, Le Cesne A, Berissi S, Terrier P, Bonvalot S, Vanel D, Auperin A, Le Pechoux C, Bui B, Coindre JM, Robert C. Clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma) of soft parts: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012: 984096. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/984096. (Epub 2012 May 30).

De Beuckeleer L, De Schepper A, Vandevenne J, et al. MR imaging of clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma of the soft parts): a multicenter correlative MRI-pathology study of 21 cases and literature review. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29:187–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002560050592.

Ibrahim RM, Steenstrup Jensen S, Juel J. Clear cell sarcoma—a review. J Orthop. 2018;15(4):963–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2018.08.039. (Erratum in: J Orthop. 2020;24:291).

Kuiper DR, Hoekstra HJ, Veth RP, Wobbes T. The management of clear cell sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29(7):568–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0748-7983(03)00115-x.

Kawai A, Hosono A, Nakayama R, Matsumine A, Matsumoto S, Ueda T, Tsuchiya H, Beppu Y, Morioka H, Yabe H, Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a study of 75 patients. Cancer. 2007;109(1):109–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22380.

Clark MA, Johnson MB, Thway K, Fisher C, Thomas JM, Hayes AJ. Clear cell sarcoma (melanoma of soft parts): the Royal Marsden Hospital experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(7):800–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2007.10.006.

Steger GG, Wrba F, Mader R, Schlappack O, Dittrich C, Rainer H. Complete remission of metastasised clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27(3):254–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-5379(91)90509-c.

Ferrari A, Casanova M, Bisogno G, Mattke A, Meazza C, Gandola L, Sotti G, Cecchetto G, Harms D, Koscielniak E, Treuner J, Carli M. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses in pediatric patients: a report from the Italian and German Soft Tissue Sarcoma Cooperative Group. Cancer. 2002;94(12):3269–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10597.

Cornillie J, van Cann T, Wozniak A, Hompes D, Schöffski P. Biology and management of clear cell sarcoma: state of the art and future perspectives. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(8):839–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2016.1197122. (Epub 2016 Jun 20).

van Akkooi AC, Verhoef C, van Geel AN, Kliffen M, Eggermont AM, de Wilt JH. Sentinel node biopsy for clear cell sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32(9):996–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.044.

Lucas DR, Nascimento AG, Sim FH. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues. Mayo Clinic experience with 35 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16(12):1197–204. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199212000-00006.

Deenik W, Mooi WJ, Rutgers EJ, Peterse JL, Hart AA, Kroon BB. Clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma) of soft parts: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Cancer. 1999;86(6):969–75.

Hantschke M, Mentzel T, Rütten A, Palmedo G, Calonje E, Lazar AJ, Kutzner H. Cutaneous clear cell sarcoma: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 12 cases emphasizing its distinction from dermal melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(2):216–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c7d8b2.

Falconieri G, Bacchi CE, Luzar B. Cutaneous clear cell sarcoma: report of three cases of a potentially underestimated mimicker of spindle cell melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34(6):619–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182473190.

Schwede K, Wetzig T, Simon JC, Fischer L, Wickenhauser C, Schärer L, Ziemer M. Cutaneous clear cell sarcoma in a 12-year-old boy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11(8):757–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.12099. (in German).

Park BM, Jin SA, Choi YD, Shin SH, Jung ST, Lee JB, Lee SC, Yun SJ. Two cases of clear cell sarcoma with different clinical and genetic features: cutaneous type with BRAF mutation and subcutaneous type with KIT mutation. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(6):1346–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12480.

Kiuru M, Hameed M, Busam KJ. Compound clear cell sarcoma misdiagnosed as a Spitz nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(11):950–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12197. (Epub 2013 Aug 27).

Gambichler T, Pantelaki I, Othlinghaus N, Moritz RK, Stricker I, Skrygan M. Deep intronic point mutations of the KIT gene in a female patient with cutaneous clear cell sarcoma and her family. Cancer Genet. 2012;205(4):182–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.02.001.

Feasel PC, Cheah AL, Fritchie K, Winn B, Piliang M, Billings SD. Primary clear cell sarcoma of the head and neck: a case series with review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43(10):838–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12755. (Epub 2016 Jul 15).

Sidiropoulos M, Busam K, Guitart J, Laskin WB, Wagner AM, Gerami P. Superficial paramucosal clear cell sarcoma of the soft parts resembling melanoma in a 13-year-old boy. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(2):265–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12058. (Epub 2012 Dec 10).

Obiorah IE, Brenholz P, Özdemirli M. Primary clear cell sarcoma of the dermis mimicking malignant melanoma. Balkan Med J. 2018;35(2):203–7. https://doi.org/10.4274/balkanmedj.2017.0796. (Epub 2017 Oct 26).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the department of pathology of Arrazi Hospital and department of orthopedic surgery of Mohammed VI University Hospital Center of Marrakesh for the support.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SA and IB wrote and revised the main manuscript. IB prepared the figures. AS, IA, and HR reviewed the references. HR and IA reviewed the entire manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdouh, S., Boujguenna, I., Soleh, A. et al. Navigating diagnostic challenges—distinguishing malignant melanoma and clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 18, 249 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04542-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04542-y