Abstract

Background

Eosinophilic enterocolitis is a rare disorder characterized by abnormal eosinophilic infiltration of the small intestine and the colon.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 29-year-old White man, who presented with an acute bowel obstruction. He had a history of a 2 months non-bloody diarrhea. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) and a MR enterography showed a multifocal extensive ileitis. White blood cell and eosinophilic polynuclei count was elevated (700/mm3). Ileo-colonoscopy showed normal ileum and segmental petechial colitis. Pathology showed a high eosinophilic infiltration in the colon. The patient was treated with steroids, with a clinical, biological and radiological recovery.

Conclusion

Eosinophilic enterocolitis should be kept in mind as a rare differential diagnosis in patients presenting with small bowel obstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eosinophilic enterocolitis (EC) is a rare condition included in the group of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs). It is characterized by a high eosinophilic infiltration in the gut wall [1]. EC may be primary, without a known etiology, or secondary to an identified cause [2]. There is a slight female and Caucasian preponderance. The clinical presentation is variable and symptoms of abdominal pain, weight loss, diarrhea, bloody stools, and malabsorption are described. When the whole bowel wall is involved, intestinal obstruction and even perforation may be seen [3]. Peripheral eosinophilia is inconstant. The definitive diagnosis is made on biopsy [4].

Case presentation

A 29-year-old smoking White man, without any personal or family history, was hospitalized in our department for the management of a small bowel obstruction (SBO). There was no fever or night sweats. The general condition was preserved. He had a history of a 2 months non-bloody diarrhea (5 stools/day). At presentation, physical examination revealed marked abdominal distension, diffuse tympanism with tenderness without rebound tenderness. There was no fever and vital signs were stable. Neurological and cutaneous examinations were normal. Examination of the anal margin and the rectal examination were normal.

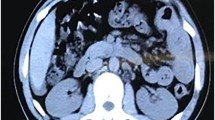

Abdominal CT scan revealed segmental, multifocal thickened small intestinal walls (8 mm) and dilated loops in the small bowel (up to 41 mm). The thickening was circumferential with a target appearance due to submucosal oedema.

White blood cell and eosinophilic polynuclei count was elevated (700/mm3). Hemoglobin value was 12.8 g/dl and platelet count was within normal ranges. The C-reactive protein value was elevated (96 µmol/l). Liver and kidney function tests were normal. The SBO had improved with conservative management.

Parasitological examination of stool and stool culture were negative. Quantiferon, ASCA, PANCA and anti-transglutaminase antibodies were negative. LDH levels were normal.

The MR enterography showed a discontinuous multifocal inflammatory thickening of the ileum (Fig. 1). Ileo-colonoscopy showed normal ileum and segmental petechial colitis. Pathology was normal for ileal biopsies and showed a catarrhal0 colitis with high eosinophilic infiltration without epithelial architectural changes for colonic biopsies (Fig. 2). The gastroscopy showed a congestive and petechial gastropathy. Pathology was normal for esophageal and duodenal biopsies and showed chronic gastritis without HP for gastric biopsies.

The patient did not have antibiotics, since the Parasitological examination of stool and stool culture were negative. He was diagnosed with primary eosinophilic enterocolitis. He received corticosteroid therapy. We observed the resolution of the subocclusives syndromes, the diarrhea and the biological inflammatory syndrome, the normalization of the PNE level. Control MR enterography was normal three months after corticosteroid therapy. Since the patient was asymptomatic, we did not do a second look endoscopy.

After a year, the patient was asymptomatic and the biological tests were normal.

Discussion

EGID is an uncommon, chronic condition of the digestive tract, characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal wall, typically involving the stomach, small intestines, and, less commonly, the colon [5]. Peripheral eosinophilia is inconstant. EC is the rarest reported form of EGID, with only few reported cases in adults, although there has been a rise over the last decade. In a large-scale retrospective epidemiological study conducted in the United States, the incidence of EC was 3.7 per 100,000 population, and that of primary EC was 2.4 per 100,000 population [6, 7]. It most often occurs between the third and fifth decades of life.

EC can be classified as primary or secondary [2]. Secondary EC results from either an eosinophilic disorder, such as a hypereosinophilic syndrome, or pathologies unrelated to an eosinophilic disorder, such as inflammatory bowel diseases, parasitic infections, certain drugs and systemic diseases (Table 1). In the majority of cases, primary EC are related to an allergic reaction, either IgE-mediated and at the origin of an anaphylactic type of food allergy, or not mediated by IgE and at the origin of food enteropathy, with milk proteins being the main food involved in children’s EC [8]. The most common allergic diseases associated with EC are rhinitis, eczema and asthma [7].

Symptoms of EC are not disease-specific [9]. Diarrhea is the most frequent symptom, present in more than 60% of cases, while rectal bleeding is only found in 10 to 20% of the cases studied. Abdominal pains are also common, being observed in 60 to more than 80% of cases. Nausea and vomiting were noted in about 30% of cases. A minimal loss of weight is also possible [7].

The presentation of EC tends to depend on which intestinal layer is most affected by the eosinophilic infiltration. In 1970, Klein et al. divided these diseases into three types depending on the depth of eosinophilic infiltration (Table 2) [10].

EC may also present as perianal disease [11], chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction [12], and appendicitis [13].

Laboratory tests are of limited value due to their low sensitivity and specificity. The blood eosinophilia is a good biological marker but is not constant and is sometimes transient [14]. In adults, the increase in serum total IgE levels is also inconstant and the search for IgE specific to certain foods is almost always negative. Atopy prick-tests and patch-tests are not recommended for diagnosing food allergies due to their limited diagnostic value.

Non-specific endoscopic findings, such as patchy areas of mucosal edema, punctate erythema, elevated lesions, pale granular mucosa and aphthous ulceration, may be seen, although these findings are uncommon and in most cases the mucosa is endoscopically normal [15]. There is no consensus concerning the physiological levels of eosinophils in the colonic mucosa [2]. Some authors have suggested that an eosinophil level of more than 40 per HPF in at least 2 different colonic segments is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of EC [2].

Management of EC is based essentially on case series and expert opinion [3].

The uses of elimination diets have been shown to improve clinical symptoms and reduce mucosal eosinophils but its efficacy depends mainly on patient compliance [16]. Symptomatic and histologic remission has been described with exclusively elemental diets and may be used as a steroid-sparing option [17]. Corticosteroid therapy (0.5–1 mg/kg/d tapered over 2–4 weeks) are considered first line pharmacological treatment [3]. Budesonide is an alternative that has also been shown to be effective with fewer side effects [18].

Multiple studies have reported efficacy and safety of Ketotifen—a histamine H1 receptor antagonist- and have proposed it as an alternative to corticosteroids [19]. The role of Montelukast, a selective leukotriene D4 receptor antagonist is still debated [20]. Finally, as there are similarities in the pathogenesis of EC with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), biologic medications undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of EoE are potential therapeutic agents for EC (Anti-IL5, anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) [4].

Conclusion

Eosinophilic enterocolitis should be considered as a rare differential diagnosis in patients presenting with small bowel obstruction.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available.

Abbreviations

- EC:

-

Eosinophilic colitis

- EGIDs:

-

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders

- SBO:

-

Small bowel obstruction

- CT scan:

-

Computed tomography scan

- PNE:

-

Eosinophilic polynuclei

- EoE:

-

Eosinophilic esophagitis

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor α

References

Impellizzeri G, Marasco G, Eusebi LH, Salfi N, Bazzoli F, Zagari RM. Eosinophilic colitis: a clinical review. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(6):769–73.

Macaigne G. Eosinophilic colitis in adults. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44(5):630–7.

Walker MM, Potter MD, Talley NJ. Eosinophilic colitis and colonic eosinophilia. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2019;35(1):42–50.

Uppal V, Kreiger P, Kutsch E. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50(2):175–88.

Huang FC, Ko SF, Huang SC, Lee SY. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with perforation mimicking intussusception. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(5):613–5.

Alfadda AA, Storr MA, Shaffer EA. Eosinophilic colitis: epidemiology, clinical features, and current management. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4(5):301–9.

Jensen ET, Martin CF, Kappelman MD, Dellon ES. Prevalence of eosinophilic gastritis, gastroenteritis, and colitis: estimates from a national administrative database. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(1):36–42.

Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):11–28 (quiz 29).

Guajardo JR, Plotnick LM, Fende JM, Collins MH, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders: a world-wide-web based registry. J Pediatr. 2002;141(4):576–81.

Klein NC, Hargrove RL, Sleisenger MH, Jeffries GH. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1970;49(4):299–319.

Lee FI, Costello FT, Cowley DJ, Murray SM, Srimankar J. Eosinophilic colitis with perianal disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78(3):164–6.

Je L, Kt K, Et K. Eosinophilic enterocolitis and visceral neuropathy with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28(4):368–71.

Tran D, Salloum L, Tshibaka C, Moser R. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis mimicking acute appendicitis. Am Surg. 2000;66(10):990–2.

Aceñero MJF. Eosinophilic colitis: experience in a large tertiary hospital. Rom J MorpholEmbryol. 2017;58:783–9.

Turner KO, Sinkre RA, Neumann WL, Genta RM. Primary colonic eosinophilia and eosinophilic colitis in adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(2):225–33.

Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, Furuta GT, Markowitz JE, Fuchs G, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):456‑63, 463.e1–3.

Khan S, Orenstein SR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis masquerading as pyloric stenosis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(1):55–7.

Siewert E, Lammert F, Koppitz P, Schmidt T, Matern S. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with severe protein-losing enteropathy: successful treatment with budesonide. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38(1):55–9.

Katsinelos P, Pilpilidis I, Xiarchos P, Christodoulou K, Papagiannis A, Tsolkas P, et al. Oral administration of ketotifen in a patient with eosinophilic colitis and severe osteoporosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(4):1072–4.

Quack I, Sellin L, Buchner NJ, Theegarten D, Rump LC, Henning BF. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis in a young girl—long term remission under Montelukast. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:24.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgment.

Funding

The authors certify that no financial and/or material support was received for this research or the creation of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS drafted the manuscript. AN participated in the design of the manuscript. NH performed the bibliographic research. BB conceived the study. RE participated in coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Smaoui, H., Nakhli, A., Hemdani, N. et al. Eosinophilic enterocolitis: a case report. J Med Case Reports 18, 22 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04319-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04319-9