Abstract

Background

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), defined by thrombotic events or obstetric complications in the presence of persistently high antiphospholipid antibodies, is characterized by a wide variety of clinical presentations and the effects of vascular occlusion can impact almost any organ system or tissue. Since adult-onset APS classification criteria are not well verified in pediatrics (where pregnancy-related problems are rare), estimating childhood prevalence is challenging. Stroke and pulmonary embolism are thromboembolic events occurring in children that can cause considerable long-term morbidity. Children with APS are more prone to recurrent thromboembolism than adults. Cutaneous symptoms are prominent and typically represent the first clue of APS. Although dermatologic findings are exceedingly heterogeneous, it is essential to consider which dermatological symptoms justify the investigation of antiphospholipid syndrome and the required further management.

Case presentation

We describe a seven-year-old Iranian boy with retiform purpura and acral cutaneous ischemic lesions as the first clinical presentation of antiphospholipid syndrome in the setting of systemic lupus erythematous.

Conclusion

APS in pediatrics, is associated with a variety of neurologic, dermatologic, and hematologic symptoms. Therefore, it is essential for pediatricians to be aware of the rare appearance of Catastrophic APS as an initial indication of APS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a rare autoimmune condition in children. Pediatric APS appears to be under-recognized because there are no universally accepted and verified criteria. For most researchers, the term "pediatric APS" applies if the classification criteria for adult-onset APS are fulfilled in patients below the age of 18 years [1,2,3]. Pediatric and adult-onset APS have distinct laboratory and clinical features. Adult-onset disease has a pronounced female predominance, whereas childhood disease has a more even gender split [4].

Catastrophic APS (CAPS) is a serious medical and potentially life-threatening state when occlusions in the microvascular system extend to critical organs such as the heart, lungs, and kidneys. In children, the prognosis for CAPS is poor, with roughly one-fourth of CAPS patients leading to death [1, 2].

The occurrence of systemic thromboembolic events is commonly documented in APS patients. One of the peculiar aspects of thrombosis is the presence of isolated microthrombosis. The cutaneous microvascular occlusion syndrome (MVOS) is a prominent form of micro thrombosis that manifests in the skin; It is a group of clinically significant skin lesions characterized by retiform purpura, purpura fulminant, non-inflammatory bland necrosis, and skin ulcers [5].

Rarely, a cutaneous manifestation of APS, including livedo reticularis, necrotizing vasculitis, thrombophlebitis, ulcerations, or pointed subungual hematoma, may be the first presentation of APS. In addition, pediatric APS has been associated with exceptional cases of epidermal necrosis and intravascular thrombosis in the dermal vessels [6].

Vessel wall damage or vessel lumen obstruction (thrombotic or embolic disease) are two possible mechanisms that can compromise natural blood flow—identifying the mechanisms that cause retiform purpura can aid in determining the etiology of this crucial dermatologic sign. Applying a systematic approach promotes the precision and agility of diagnosis and finding an appropriate treatment [5].

It is clear that skin can be potentially involved in the course of APS. In this regard, all should be aware of the simultaneous presentation of cutaneous microthrombi representing as retiform purpura in the setting of pediatric APS. Only a few cases have documented the dermatological manifestation of cutaneous MVOS in pediatric APS with or without systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), suggesting that the problem is underdiagnosed [7].

Here, we report a pediatric case of Lupus-associated APS in a child who presented as a Cutaneous MVOS. The importance of the current report lies in the awareness of the simultaneous presentation of cutaneous microthrombi in pediatric APS.

Case presentation

A 7-year-old Iranian boy with no remarkable past medical history was brought to the emergency department with severe pain in his right thumb, agitation, skin color changes, and swelling of his both hands, feet, and lips. The patients and his parents did not note the personal and family history of any rheumatologic disorders or occurrence of thromboembolism accidents.

A week before admission, he experienced gradual development of acral color changes in addition to the bluish discoloration of his lips and tongue in association with low-grade fever; after initiation of symptoms, he was admitted to the hospital for three days and given intravenous cephazolin. Cutaneous examination revealed demarcated bluish discoloration in acral sites, including the ears, hands, feet, and the mouth and extensor surface of the limbs, in combination with intense pain (Figs. 1 and 2). Notable findings included bilaterally, non-blanching, and retiform purpuric plaques on the first digit of the right hand and second and third digits of the right leg and ischemic nail beds of the first finger which were tender. The most prominent lesions measure 2 cm by 3 cm in size.

Thrombotic mechanisms mediated by aPL. Vascular dysfunction, inflammatory cell infiltration, and complement deposition all play a critical role in the pathogenesis of APS, as depicted in the illustration. First, the presence of aPL initiates clotting, which in turn activates another procoagulant state, the so-called “second hit”, to induce complete clot formation, which appears to necessitate complement activation in vivo. When immunogenic phospholipid-binding proteins such as β2GPI and prothrombin are cross-linked by aPL, cellular activation can be evoked. aPL increases endothelial leukocyte adhesion, cytokine secretion, and PGE2 synthesis by upregulating tissue factor expression on endothelial cells and monocytes. Excessive endosomal reactive oxygen species generation in monocytes, the neutrophil release of prothrombotic extracellular traps (NETosis), and complement activation on the surface of endothelium and other cell types significantly intensify inflammation and thrombosis formation. aPL, antiphospholipid autoantibodies; β2GPI, β2 glycoprotein I; LACA, Lupus anticoagulant antibody; ACLA, anticardiolipin antibody; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PBP, phospholipid-binding protein

He had a blood pressure of 110/80 mm Hg and a heart rate of 130 beats per minute. His respiratory rate was 30 breaths/min, with an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The distal pulse of all four extremities dose not reveal any abnormality. He rapidly developed dusky red and vesiculobullous formations during the first 24 h of admission, which advanced to the apparent ischemic lesions. The abdomen was neither distended nor tender; there was no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. The oral and vaginal mucosa appeared normal. Aside from the skin lesions, the child's agitation commenced a few hours before being admitted to the hospital, deteriorating his interactiveness.

During the hospitalization and subsequent follow-up, analyses in the laboratory indicated elevation in the levels of anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I (total anti-β2GPI = 19.1 U/ml [Normal range: < 16]), anticardiolipin (aCL IgG = 15.1 U/ml [Normal range: < 10U/ml]) IgG, Lupus Anticoagulant (LAC = 90 [Normal range: < 40]), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR = 103 mm/hr), positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (ds-DNA) antibody, and hypocomplementemia were detected during thrombophilia screening (Table 1). No abnormal findings were found in the patient's chest radiography, brain CT scan, abdominal sonography, echocardiography, and limb doppler sonography.

During the first day of admission, there was an alteration in the level of consciousness manifested by agitation, which cannot be explained solely by the discomfort in the purpuric areas of the acral regions.

The patient's treatment plan was supplemented with broad-spectrum antibiotics and three corticosteroid pulses (methylprednisolone 10 mg/kg), which were then converted to oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/d) on the seventh day of hospitalization, therapeutic heparin. Furthermore, every other day, he received plasmapheresis five times.

There was an improvement in consciousness after 24 h of initiation of the treatment. Ecchymotic lesions resolved on the feet after the sixth day of therapy. Perioral ecchymotic lesions were also alleviated. Based on clinical examination and laboratory findings, the possible diagnosis of cutaneous MVOS is probably in the APS setting (Fig. 2).

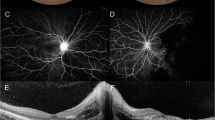

After 2 weeks of admission, the patient was discharged with prednisolone and enoxaparin and was advised to return to the pediatric rheumatologist. On the follow-up examination and repeat of the laboratory test that showed anti-β2GPI IgG was 1.22, β2GPI IgM was 0.97, and aCL IgG was 2.64, the diagnosis of Lupus-associated APS was made, and the patient underwent regular follow-up (Fig. 3).

Discussion

We described a child successfully treated with plasmapheresis via femoral access for cutaneous (MVOS) manifested as neurologic involvement, retiform purpura, and digital gangrene subsequent to SLE-associated APS.

Cutaneous MVOS is typically caused by thrombotic, infectious, or embolic phenomena and can be used to identify associated critical systemic conditions and prevent potentially life-threatening and organ-threatening complications through prompt identification and treatment of the comorbid conditions [8]. Cutaneous lesions linked with MVOS are often incorrectly identified as cutaneous vasculitis or misinterpreted as systemic diseases [9]. In CAPS, identification of these clinical manifestations that often precede the occurrence of thrombosis is critical for as soon as possible proper treatment [10].

Our patient’s agitation was not exclusively due to the discomfort in the purpuric portions of the acral regions but rather a change in the patient's degree of consciousness. Antiphospholipid antibodies and activated inflammatory mediators may have a role in the etiology of certain neurological correlations, according to studies. APS induces a hypercoagulable condition, which may explain why thromboembolic cerebrovascular episodes are more common in people with APS. Cerebral thrombosis is often the cause of neurological symptoms; thus, many different factors, including elevated levels of aPLs, homocysteine, fibrinogen, protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III, can be considered risk factors [1].

Our patient’s therapeutic approach included a combination of anticoagulation and steroids, as well as attempts to achieve a rapid reduction in aPL titer using plasmapheresis. The infection has been implicated as a contributing triggering factor in CAPS. Fever and leukocytosis at presentation may indicate a condition that precipitated CAPS [2]. As a result, broad-spectrum antibiotics were prescribed for our case and were discontinued after eight days based on negative blood culture results.

Dermatologic characteristics observed in our patient narrow the differential diagnosis to Cutaneous MVOS, which is defined by a clinically significant skin lesion manifesting as retiform purpura and bland necrosis without inflammation. Although dermatologic manifestations are nonspecific and not included in the classification criteria, these abnormalities may be the initial presenting feature, making them essential in identifying this disease [11].

APS and cutaneous lesions associated with MVOS are frequently misdiagnosed as cutaneous vasculitis or interpreted as systemic disorders; accordingly, prompt and proper management is critical to the outcome of MVOS [12]. For that reason, it is necessary to be familiar with these cutaneous features and recognize when an APS investigation should be pursued.

Conclusion

Even though pediatric APS has the potential to cause significant morbidity, it remains a challenging condition. Pediatric APS, probably more frequently than adult APS, is associated with a variety of neurologic, dermatologic, and hematologic symptoms (—both in children with lupus and in children with primary APS. Concludingly, it is essential for pediatricians to be aware of the rare appearance of CAPS as an initial indication of APS. The detailed clinical course, precisely the cutaneous manifestations, should be gathered and studied more thoroughly.

Availability of data and materials

Upon written request, the corresponding author will provide the data used to support the findings and conclusions.

Abbreviations

- APS:

-

Antiphospholipid syndrome

- aPL:

-

antiphospholipid autoantibodies

- CAPS:

-

Catastrophic APS

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- LAC:

-

Lupus anticoagulant

- N.A.:

-

Not applicable

- P.T.:

-

Prothrombin time

- PTT:

-

Partial thromboplastin time

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- AT III:

-

Anti-thrombin III

- FDP:

-

Fibrin degradation products

- A.B:

-

Antibiotics

- MPT:

-

Methylprednisolone pulse therapy

- P.P:

-

Plasmapheresis

- LOC:

-

Level of consciousness

- MVOS:

-

Microvascular occlusion syndrome

References

Sarecka-Hujar B, Kopyta I. Antiphospholipid syndrome and its role in pediatric cerebrovascular diseases: a literature review. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8(10):1806–17.

Rosina S, Chighizola CB, Ravelli A, Cimaz R. Pediatric antiphospholipid syndrome from pathogenesis to clinical management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2021;23(2):1.

Groot N, De Graeff N, Avcin T, Bader-Meunier B, Dolezalova P, Feldman B, et al. European evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of paediatric antiphospholipid syndrome: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(10):1637–41.

Wincup C, Ioannou Y. The differences between childhood and adult onset antiphospholipid syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2018;6(November):1–10.

Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(4):783–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112.

Caporuscio S, Sorgi ML, Nisticò S, Pranteda G, Bottoni U, Carboni I, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in antiphospholipid syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2015;28(2):270–3.

Camacho-Lovillo S, Bernabeu-Wittel J, Iglesias-Jimenez E, Falcõn-Neyra D, Neth O. Recurrence of cutaneous necrosis in an infant with probable catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(4):2012–3.

Pichler WJ. An approach to the patient with drug allergy. UpToDate. 2016;24(3):151–72.

Li JY, Ivan D, Patel AB. Acral retiform purpura. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31362-4.

Tarango C, Palumbo JS. Antiphospholipid syndrome in pediatric patients. Curr Opin Hematol. 2019;26(5):366–71.

Sciascia S, Amigo MC, Roccatello D, Khamashta M. Diagnosing antiphospholipid syndrome: “extra-criteria” manifestations and technical advances. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(9):548–60.

Francès C, Niang S, Laffitte E, Le Pelletier F, Costedoat N, Piette JC. Dermatologic manifestations of the antiphospholipid syndrome: two hundred consecutive cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(6):1785–93.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors of this article received no financial support for their research, drafting, or publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BAN: writing and editing the manuscript, data gathering, revising the manuscript, and approving the final version; NSH: writing the initial draft, reviewing the literature, and illustrating the figures; AGH, HR: revising the manuscript, patient management, and conceptualization; BS, SHB: revising the manuscript, collecting attributed data and patient management; MPB: editing the manuscript and collecting attributed data. All authors have approved the final version to be published. All authors are committed to being accountable for all aspects of the work, including investigating and resolving any issues regarding the accuracy or integrity of any section of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran, approved this report's ethical content (IR.ARI.MUI.REC.1401.099). Participation in the study was contingent upon signing a written informed consent form signed by the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's legal guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors verified that they had no competing interests in line with the research objectives, authorship, or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseini, NS., Babaei, S., Rahimi, H. et al. Cutaneous microvascular occlusion syndrome as the first manifestation of catastrophic lupus-associated antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Reports 17, 375 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04068-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04068-9