Abstract

Background

Biologics dramatically improve symptoms of severe asthma; however, various exacerbating factors may induce flare-up. Pneumocystis spp. have not been reported as a cause of asthma exacerbation during biologic use, although patients with severe asthma have high levels of antibodies against Pneumocystis spp.

Case presentation

An 87-year-old female with severe asthma that was well-controlled with mepolizumab, who developed a steroid-resistant refractory flare-up. Chest computed tomography showed bilateral ground glass opacities, and results of polymerase chain reaction tests on induced sputum were positive for Pneumocystis DNA. Therefore, a diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia was made. The clinical symptoms improved after treatment with sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of Pneumocystis pneumonia as a cause of refractory exacerbation of bronchial asthma during use of interleukin-5 inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although the primary treatment for severe bronchial asthma is high-dose inhaled steroids and systemic administration of steroids, symptom control has improved dramatically since the availability of biologic agents [1]. However, some patients experience exacerbations of bronchial asthma even during the use of biologic agents. The causes include allergen exposure; viral, bacterial, and fungal infections; environmental factors such as cold stimuli [2]; and the production of neutralizing antibodies to biologic agents [3], and it is difficult to control symptoms without eliminating the causes. Consequently, steroid dosage may have to be increased even when biologic agents are used.

Pneumocystis jirovecii, a species of the genus Pneumocystis, is a pathogenic microorganism that causes Pneumocystosis in immunocompromised hosts; the primary site of infection is the lung, and Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is common [4]. It is noteworthy that PCP is frequently observed in patients administered steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and biologic agents for rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease [5]. However, a higher percentage of children and adults with severe asthma have antibodies against Pneumocystis spp. [6, 7]. Furthermore, Pneumocystis spp., like other allergens, are airway allergens that cause Th2-type airway inflammation [7].

Mepolizumab, an anti-interleukin (IL) -5 antibody, improves bronchial asthma symptoms by inhibiting IL-5-mediated proliferation and activation of eosinophils. However, there is no report of severe bronchial asthma complicated by Pneumocystis pneumonia during mepolizumab therapy, and the association is unclear.

We report a case of a patient with severe bronchial asthma that was well-controlled with mepolizumab, who subsequently developed a steroid-resistant exacerbation caused by PCP.

Case presentation

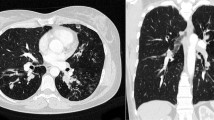

An 87-year-old female with a history of glaucoma and bronchial asthma had been visiting the hospital for fourteen years. Her asthma phenotype was an elderly onset eosinophil-predominant, non-atopic type. She repeatedly visited the emergency room two to three times a year due to exacerbations, and each time she was treated with 20 mg of prednisolone (PSL) orally for five days. Recently, she was treated with high-dose fluticasone furoate/vilanterol and montelukast, in addition to mepolizumab, which resulted in better control and no exacerbation for one year. Thereafter, she was admitted to the hospital due to worsening bronchial asthma, mainly coughing and persistent low-grade fever of approximately 37 °C. Results of sputum Gram staining were negative, and chest radiographs showed no obvious pneumonia. She was diagnosed with exacerbation of bronchial asthma and treatment with 120 mg/day of methylprednisolone intravenously was initiated; however, the patient's cough, wheezing, and low-grade fever did not resolve. After two weeks of hospitalization, although she had no human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, we considered opportunistic infection as the source of fever. Chest computed tomography showed ground glass opacities in the bilateral lung fields (Fig. 1), and a diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia was made based on an elevated βD-glucan level of 36.4 pg/mL and positive polymerase chain reaction test results for Pneumocystis DNA in the induced sputum, despite negative speculum examination. Sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (SMX–TMP) was initiated, her fever resolved, and asthma symptoms improved in approximately one week (Fig. 2). Since then, the patient has been treated with dupilumab as a biologic agent and has not had an asthma exacerbation or used systemic steroids for more than one year.

Discussion and conclusions

Our patient who had a steroid-resistant exacerbation of bronchial asthma during mepolizumab therapy was diagnosed with PCP based on ground-glass opacities on computed tomography and positive polymerase chain reaction test results for Pneumocystis DNA in the sputum. The patient was treated with SMX–TMP, which improved her symptoms. Therefore, PCP was considered as a possible cause of bronchial asthma exacerbation during anti-IL-5 antibody therapy.

There are two types of PCP: HIV-associated PCP, which occurs in patients with immunosuppression due to HIV infection, and non-HIV-associated PCP, which develops independently of HIV infection. Non-HIV-associated PCP has an acute course and is more severe than HIV-associated PCP. Moreover, the amount of pathogen at the time of infection is low and difficult to detect on speculum examination [8]. The pathogenesis of non-HIV-associated PCP is believed to be associated with an excessive immune response and correlated with inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ [9, 10]. In mice, loss of STAT6, a transcription factor involved in Th2 cell differentiation, suppresses bronchial hypersensitivity [9]. Since Th2-type inflammatory responses are strongly associated with airway hypersensitivity symptoms in non-HIV-associated PCP, Pneumocystis spp. infection may have contributed to exacerbation and refractoriness of asthma symptoms in this case.

Pneumocystis spp. carriage rates range from 16–55% and 0–65% in patients with COPD and patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, respectively [11]. Although there is no report on the rate of carriage in people with asthma, it is highly likely that our patient was carrying the disease, since anti-Pneumocystis antibodies are higher in patients with severe asthma and in older patients [7]. In this patient, PCP developed in the absence of any background HIV infection or disease indicating compromised immunity. In general, 16 mg/day of PSL for > 8 weeks increases the risk of developing PCP [12], and prophylactic administration of SMX–TMP is recommended when 20 mg/day of PSL is administered for ≥ 4 weeks [13]. In the present case, the patient had received < 5 mg/day of PSL previously and 10 mg/day of PSL for two weeks prior to admission. Therefore, no prophylactic SMX–TMP was administered because the dose and duration of PSL did not indicate the need for prophylactic SMX–TMP administration. Thus, other factors were possibly involved in the pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia.

First, this patient is quite elderly and it is expected that there will be some natural deviations in immune response in the lungs with aging [14]. Next, she had a high systemic glucocorticoid load according to frequent exacerbations and OCS dosing in previous years. A high OCS load is a known risk factor for severe side effects and/or complications in many clinical situations, including infectious diseases [15, 16]. And finally, the use of anti-IL-5 antibodies. IL-5 is the most potent activator of eosinophils and is produced by Th2 cells and ILC2s. Eosinophils have immunomodulatory functions in allergic diseases as well as in bacterial, fungal, and viral infections [17], and have been implicated in immunity against Pneumocystis spp. [18]. They have been shown to have killing activity against Pneumocystis spp. in a mouse model [18], suggesting that immunity against Pneumocystis jiroveci may be mediated by eosinophils in humans as well. In this case, the decrease in eosinophils caused by the use of an anti-IL5 antibody may have been responsible for the development of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Therefore, we chose dupilumab, which suppresses eosinophil activity by indirectly reducing IL-5 via Th2 cells through IL-4 inhibition, rather than direct suppression through IL-5 inhibitors, as the next biologic treatment for this patient with eosinophilic asthma.

In conclusion, Pneumocystis sp. infection should be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients with severe asthma that has been well controlled with biologic agents who develop refractory exacerbations.

Abbreviations

- PCP:

-

Pneumocystis pneumonia

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- PSL:

-

Prednisolone

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- SMX–TMP:

-

Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim

References

McGregor MC, Krings JG, Nair P, Castro M. Role of biologics in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(4):433–45. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201810-1944CI.

Trevor J, Lugogo N, Carr W, Moore WC, Soong W, Panettieri RA Jr, Desai P, Trudo F, Ambrose CS. Severe asthma exacerbations in the United States: incidence, characteristics, predictors, and effects of biologic treatments. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127(5):579-587.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2021.07.010.

Matsumoto-Sasaki M, Shimizu K, Suzuki M, Suzuki M, Nakamaru Y, Konno S. A case of severe asthma switched to mepolizumab due to late-occurring unresponsiveness to Benralizumab. Arerugi. 2020;69(8):678–82. https://doi.org/10.15036/arerugi.69.678.

Eddens T, Kolls JK. Pathological and protective immunity to Pneumocystis infection. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37(2):153–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-014-0459-z.

Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, Ishiguro N, Tanaka Y, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N, Harigai M, Ryu J, Inoue K, Kondo H, Inokuma S, Ochi T, Koike T. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(2):189–94. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2007.072967.

Rayens E, Noble B, Vicencio A, Goldman DL, Bunyavanich S, Norris KA. Relationship of Pneumocystis antibody responses to paediatric asthma severity. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021;8(1): e000842. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000842.

Eddens T, Campfield BT, Serody K, Manni ML, Horne W, Elsegeiny W, McHugh KJ, Pociask D, Chen K, Zheng M, Alcorn JF, Wenzel S, Kolls JK. A novel CD4+ T cell-dependent murine model of pneumocystis-driven asthma-like pathology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(7):807–20. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201511-2205OC.

Reid AB, Chen SC, Worth LJ. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in non-HIV-infected patients: new risks and diagnostic tools. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(6):534–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834cac17.

Swain SD, Meissner NN, Siemsen DW, McInnerney K, Harmsen AG. Pneumocystis elicits a STAT6-dependent, strain-specific innate immune response and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(3):290–8. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2011-0154OC (Epub 2011 Sep 29).

Kelly MN, Shellito JE. Current understanding of Pneumocystis immunology. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(1):43–65. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.09.116.

Vera C, Rueda ZV. Transmission and colonization of Pneumocystis jirovecii. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(11):979. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7110979.

Yale SH, Limper AH. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: associated illness and prior corticosteroid therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(1):5–13. https://doi.org/10.4065/71.1.5.

Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, Blouin G, Camins BC, Casper C, Cooper B, Dubberke ER, Engemann AM, Freifeld AG, Greene JN, Ito JI, Kaul DR, Lustberg ME, Montoya JG, Rolston K, Satyanarayana G, Segal B, Seo SK, Shoham S, Taplitz R, Topal J, Wilson JW, Hoffmann KG, Smith C. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2 2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(7):882–913. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2016.0093.

Cho SJ, Stout-Delgado HW. Aging and lung disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2020;10(82):433–59.

Price D, Castro M, Bourdin A, Fucile S, Altman P. Short-course systemic corticosteroids in asthma: striking the balance between efficacy and safety. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(155): 190151.

Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, Xu X, Kerkhof M, Ling Zhi Jie J, Tran TN. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:193–204.

Ravin KA, Loy M. The eosinophil in infection. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50(2):214–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-015-8525-4.

Eddens T, Elsegeiny W, Nelson MP, Horne W, Campfield BT, Steele C, Kolls JK. Eosinophils contribute to early clearance of Pneumocystis murina infection. J Immunol. 2015;195(1):185–93. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1403162.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KT and TS wrote the manuscript. YN, KM, MS, and HW assisted in treatment in hospital. YY and HC contributed to manuscript. TS had the concept and contributed to revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was sought for the clinical data, which were based on records kept as part of routine medical care.

Consent for publication

The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeda, K., Sumi, T., Nagahisa, Y. et al. Refractory flare-up of severe bronchial asthma controlled with mepolizumab due to Pneumocystis pneumonia: a case report. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 18, 35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-022-00678-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-022-00678-y