Abstract

Background

Penicillin allergy labels frequently impede guideline-directed treatment with a penicillin or other β-lactam antibiotics. Despite presumed allergy, targeted questioning may indicate a low probability of sensitization and permit reasonably safe administration of the antibiotic in question. In this study, we evaluated a standardized algorithm aiming to differentiate non-allergic patients from those with true allergic β-lactam hypersensitivity.

Methods

We retrospectively applied a de-labelling algorithm in 800 consecutive patients with suspected β-lactam hypersensitivity. All had undergone complete allergy work-up permitting to definitely exclude or diagnose β-lactam allergy between 2009 and 2019.

Results

In 595 (74.4%) out of 800 cases evaluated, β-lactam allergy could be excluded by negative challenge testing. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis was diagnosed in 70 (8.7%) patients, delayed-type hypersensitivity in 135 (16.9%). In 62 (88.6%) anaphylaxis cases, the algorithm correctly advised to use an alternative antibiotic. Accuracy was higher in patients with moderate to severe anaphylaxis (97.7%) compared to those with a history of mild reactions (73.1%). The algorithm correctly identified 122 (90.4%) patients with proven delayed-type hypersensitivity. It permitted de-labelling in 330 (55.5%) out of 595 patients with diagnostic exclusion of penicillin hypersensitivity, but failed to identify the remaining 265 (44.5%) as low-risk cases.

Conclusions

The algorithm detected 89.8% of cases with penicillin (β-lactam) allergy, sensitivity was optimal for moderate to severe anaphylaxis. Study data justify the implementation of a standardized de-labelling algorithm under close supervision in order to permit guideline-directed treatment and reduce the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics as part of an antibiotic stewardship program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Up to 10% of the population in Europe, North America, and Australia report penicillin allergy [1, 2]. Due to a label of penicillin allergy, the treating physician commonly feels compelled to administer an alternative antibiotic, even if a penicillin would be the treatment of choice. We are not aware of exact data concerning the question whether physicians refrain from prescribing the whole class of β-lactam antibiotics because of a vague report of penicillin allergy or avoid only penicillins, e.g. benzyl penicillin, phenoxymethyl penicillin, and aminopenicillins. In Germany, in our experience, all β-lactam antibiotics are usually avoided because of feared cross-reactivity, whereas in other countries a 2nd or 3rd generation cephalosporin may be used in such a situation. However, penicillin allergy labels increase the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which may further promote the problem of bacterial resistance [3,4,5]. In recent years, increasing attempts have been made in centers of allergy or infectious disease worldwide to critically question presumed penicillin allergy and, if necessary, directly de-label without testing via medical reconciliation [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. De-labelling unproven penicillin allergy is increasingly important in the fight against antibiotic resistance [3, 14, 15].

Allergic hypersensitivity to penicillins or other β-lactam antibiotics most commonly manifests either within a few minutes after intake or infusion as acute anaphylaxis or several hours to days later as measles-like (maculopapular) exanthema; other reaction patterns are less common [1, 16,17,18]. A German retrospective observational study revealed aminopenicillins to most commonly cause exanthematous delayed-type reactions, whereas IgE-mediated anaphylaxis was predominantly attributed to certain cephalosporins, e.g. cefazolin, ceftriaxone or cefuroxime [19]. The cephalosporins mentioned are often administered intraoperatively and were identified as the most important trigger of an anaphylactic incident during general anesthesia by some authors [20, 21]. These observations, however, are dependent on prescription behavior and may vary among different countries.

This study is based on a group of 800 patients with suspected β-lactam allergy, all of whom underwent standardized allergy testing including diagnostic challenge [19]. The medical history of these cases was retrospectively reviewed and critically evaluated using a de-labelling algorithm. The outcome of the algorithm was then compared with the respective results of allergy testing.

Methods

Patients

The medical history of 800 consecutive patients referred to our allergy clinic from January 2009 to December 2019 for diagnostic work-up of a hypersensitivity reaction attributed to a β-lactam antibiotic was evaluated. The institutional review board of the University Hospital Würzburg consented to retrospective review and publication of anonymized data.

Allergy testing

Allergy testing including β-lactam-specific serum IgE, patch, prick, and intradermal skin test, as well as challenge testing was performed as described previously in detail [19]. The severity of anaphylaxis was classified as mild, moderate or severe [22].

De-labelling algorithm

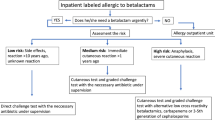

In a blinded approach, results of allergy testing were initially unknown to the investigator, and only patient’s medical history was evaluated using a modified version of our recently published de-labelling algorithm comprising five key questions (Fig. 1) [23]. The algorithm's outcome is binary, recommending either to de-label penicillin allergy (and administer the β-lactam in question) or to use an alternative antibiotic. Structure and content are briefly explained hereinafter, a critical review is included in the discussion section. Question 1 is intended to identify cases that are not indicative of allergic hypersensitivity because clinical complaints are incompatible or the time interval between intake and symptoms is clearly to long for an allergic reaction. Question 2 aims at skin reactions in childhood or adolescence without additional systemic symptoms, for which allergic penicillin hypersensitivity can be virtually excluded. Question 3 asks for a prolonged episode of urticaria without any signs suggestive of systemic anaphylaxis. Question 4 is targeted at the most common form of allergic penicillin hypersensitivity, a measles-like (maculopapular) exanthema in timely relationship with intake or administration. If the answer to questions 1-4 is either no or uncertain, question 5 needs to be addressed in order to exclude or identify potential indicators of a severe drug reaction. In addition to a close temporal relationship of only a few minutes between intake and clinical reaction, these include signs of systemic anaphylaxis, an incident during anesthesia, erosions of mucous membranes, cutaneous blisters, hepatitis, nephritis, or a sudden drop of blood cell numbers.

De-labelling algorithm applied to the medical history of 800 cases with suspected penicillin allergy [modified from (23)]

Results

The reported type of hypersensitivity reaction, the incriminated β-lactam antibiotic, and the time interval between the β-lactam-associated reaction and allergy testing in all 800 cases is shown in Table 1. In 334 cases (41.8%), patient’s history was suggestive of an immediate reaction, in 421 (52.6%) of a delayed reaction. The assignment of the remembered incident as immediate or delayed remained uncertain in 45 patients (5.6%), 30 of whom reported a time interval of more than 10 years since the β-lactam-associated reaction.

Results of allergy testing

In 595 (74.4%) cases, negative challenge testing finally excluded β-lactam hypersensitivity. The remaining 205 patients with proven β-lactam hypersensitivity were recently described in detail (Additional file 1) [19]. The diagnosis of delayed-type β-lactam hypersensitivity in 135 (16.9%) patients and IgE-mediated allergy in 70 (8.7%) was based on an overall assessment including history, reaction pattern, and results of testing.

Outcome of the algorithm

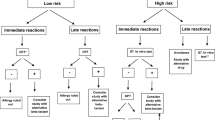

The algorithm’s outcome in all 800 cases is summarized in Fig. 2, comparing the results of patients with confirmed β-lactam allergy (n = 205) to those of non-allergic patients (n = 595). The algorithm recommended de-labelling for 21 (10.2%) patients with confirmed penicillin allergy—in real life this might have entailed re-administration of the antibiotic in question and thus an allergic reaction. On the other hand, the algorithm resulted in a recommendation to use an alternative antibiotic for 265 (44.5%) out of 595 non-allergic patients.

Outcome of the de-labelling algorithm applied to the medical history of 800 consecutive cases with suspected penicillin allergy. In 595 cases, β-lactam hypersensitivity could be definitely excluded through negative challenge testing, allergic β-lactam hypersensitivity was proven in 205 cases by positive results of skin or challenge testing

Comparison between results of allergy testing and outcome of the de-labelling algorithm

The results of allergy testing and outcome of the de-labelling algorithm are depicted in Table 2. Out of 205 cases with proven allergic penicillin hypersensitivity, the algorithm would have correctly identified 184 (89.8%) and recommended use of an alternative antibiotic. Of note, 43 out of 44 cases (97.7%) with moderate to severe anaphylaxis were correctly detected. The three patients suffering from FDE and the three DRESS patients were identified as high risk cases by question 5 due to a respective history of cutaneous blistering or hepatitis. The algorithm correctly recommended use of an alternative antibiotic in 106 out of 117 cases (90.6%) with measles-like (maculopapular) exanthema as detected by question 4. The 21 cases of incorrect de-labelling comprised 8 anaphylaxis cases (7× mild, 1× moderate) and 13 delayed-type reactions (11× measles-like exanthema, 2× SDRIFE) (Fig. 2). The algorithm correctly advised de-labelling for 330 (55.5%) out of 595 non-allergic patients, but an alternative antibiotic would have been unnecessarily recommended for the remaining 265 (44.5%). The false suspicion of penicillin allergy was mainly attributed to a history of exanthema (195 cases) and to complaints that were incorrectly interpreted as signs of a severe drug reaction (70 cases).

Discussion

The majority of patients with a penicillin allergy label have never been tested and suspected penicillin hypersensitivity remains unproven. Study data show that our standardized algorithm is a useful tool for estimating the probability of true allergic hypersensitivity, which in many cases is so low that re-administration of the β-lactam antibiotic in question may be considered sufficiently safe. Application of the algorithm is, of course, restricted to patients who are not cognitively impaired, understand the questions and are able to answer rationally. As long as evidence of safety from large prospective studies is missing, use of the algorithm should be restricted to inpatients who subsequently receive the β-lactam antibiotic in question under close medical supervision.

The capacity of allergy care in Germany and elsewhere is limited, and the large number of cases—up to 10% of the European, North American, and Australian population report a history of penicillin allergy—makes testing of all patients virtually impossible [24]. To address this problem, centers of infectious disease or allergy around the world recently developed strategies to critically question penicillin allergy labels and, if necessary, de-label and re-administer the respective antibiotic directly without testing [6,7,8,9,10]. Following a different approach, some groups advocate allergy testing directly before initiation of treatment, meaning that the β-lactam antibiotic in question may only administered if skin testing is negative at 15 minutes reading [25,26,27]. Though this strategy might permit to identify cases of IgE-mediated anaphylaxis, it does not allow exclusion of delayed-type hypersensitivity. Moreover, routine implementation of standardized allergy testing prior to antibiotic therapy is hardly realistic in practices and emergency departments due to the lack of specialized staff, equipment, and—last but not least—time.

Question 1 of the presented algorithm aims to identify reports of non-specific complaints or pharmacological side effects that have mistakenly lead to a suspicion of allergic hypersensitivity. This does include abdominal pain, palpitation, or headache—symptoms that do not indicate an allergic reaction on their own, even if interpreted as such by the patient and/or treating physician [1]. Moreover, a prolonged time interval between last intake and the onset of symptoms (>2 days to onset of urticaria, >1 week to onset of exanthema) strongly speaks against allergic hypersensitivity, provided that the patient is able to reliably recall the time course. Question 2 addresses an urticarial or exanthematous skin rash in childhood or adolescence without any further complaints which almost always results from a bacterial or viral infection and is only rarely caused by allergic hypersensitivity [28,29,30]. Penicillin-induced anaphylaxis is unlikely if medical history reveals urticaria without further systemic symptoms of e.g. respiratory tract or cardiovascular system, especially if episodes of urticaria recur several days after stopping penicillin treatment (question 3) [31]. In case of an acute urticaria episode directly after intake of a penicillin, users of the algorithm will be guided to question 5 in order to assess the risk of systemic anaphylaxis. Questions 1-3 permitted correct de-labelling in 229 non-allergic patients (question 1: n = 68, question 2: n = 66, and question 3: n = 95) while proving sufficiently safe. An incorrect recommendation to de-label which might have lead to re-administration of the respective antibiotic and thus an allergic reaction in a real life situation was given in only 11 cases (question 1: n = 3, question 2: n = 2, and question 3: n = 6) (Fig. 2).

Penicillin should be preferably avoided if question 4 is answered with yes, provided that the exanthematous rash developed during adulthood and not in childhood as addressed in question 2. Measles-like (maculopapular) exanthema generally is not a severe drug reaction (16, 32). As a consequence, the recommendation to switch to an alternative antibiotic is rather on the cautious side. Accordingly, in other published pathways exanthema is not taken into account at all [10]. Our data show that in 195 (32.8%) out of 595 non-allergic patients, an alternative antibiotic would have been recommended unnecessarily due to question 4 (Fig. 2). On the other hand, by the same question 4 recurrence of exanthema would have been prevented in 106 (51.7%) out of 205 patients with proven penicillin allergy. This type of drug reaction should not be trivialized but considered as bothersome and sometimes protracted condition, which represents an additional and potentially preventable burden for a patient already suffering from an infectious disease [32].

If none of the previous questions 1–4 could be unequivocally answered with yes, the user will be guided to question 5 addressing evidence of a severe drug reaction. Anaphylaxis usually develops within a few minutes after intake of the drug, presenting as a systemic reaction including sudden cardiovascular (e.g. arterial hypotension, tachycardia, loss of consciousness) and/or respiratory symptoms (e.g. cough, chest tightness, shortness of breath). As administration of an antibiotic is nowadays considered the most common cause of intraoperative anaphylaxis [20, 21], the algorithm specifically addresses incidents during general anesthesia. Signs of a severe drug-induced delayed reaction include painful erosions of the oral mucosa and/or cutaneous blisters, but also hepatitis, nephritis or a sudden drop of cell numbers in peripheral blood [33]. Evaluation of question 5 underlined the difficulties and limitations arising from self-reported information with regard to both exclusion and reliable detection of a potentially severe drug reaction. Based on retrospective interpretation of reported symptoms as potentially severe, an alternative antibiotic would have been unnecessarily recommended by question 5 in 70 out of 171 non-allergic patients (Fig. 2). Eighty-eight out of 205 patients with proven penicillin allergy were evaluated according to question 5; in 78 a recommendation to use an alternative antibiotic was correctly given, whereas de-labelling was recommended for the remaining 10 who probably would have developed an allergic reaction upon re-exposure of the respective antibiotic.

The PEN-FAST was recently proposed as an even more straightforward approach for de-labelling questionable penicillin allergy [10]. PEN-FAST represents a clinical decision rule consisting of five short questions resulting in a point score [PEN: penicillin allergy reported by patient (if yes, proceed with assessment), F: five years or less since reaction (2 points), A: anaphylaxis or angioedema (2 points), S: severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2 points), T: treatment required for the reaction (1 point)] [10]. A total score of less than three points was determined as cutoff value for a low risk of penicillin allergy (and thus de-labelling), whereas three or more points may indicate a higher risk (and thus administration of an alternative antibiotic). In a cohort of 622 patients, the calculated sensitivity of the PEN-FAST applying the mentioned cutoff value to identify penicillin allergy was 70.7%, specificity 78.5%, the positive predictive value was 25.3%, and the negative predictive value 96.3% [10]. The corresponding findings applying the presented algorithm in our series was a sensitivity of 89.8%, a specificity of 55.5%, a positive predictive value of 41.0%, and a negative predictive value of 94.0% (Table 2; Additional file 2). The results of these studies are not directly comparable mainly because of different populations investigated, e.g. the PEN-FAST study of total 622 cases included 58 with a positive finding in penicillin allergy testing (9.3%), whereas in our study we evaluated 800 cases including 205 with proven β-lactam hypersensitivity (25.6%). However, both de-labelling procedures seem to be quite safe as demonstrated by a high negative predictive value of >90%.

In addition to the presented data from a series of retrospective cases, a preliminary prospective study of 200 patients has demonstrated that the algorithm may be reasonably safe [23]. Data from both studies, however, demonstrate, that use of the proposed algorithm does not guarantee absolute safety. As in any other medical procedure, both the treating physician and the patient will be obliged to accept a certain residual risk which needs to be weighed against the benefits of guideline-directed antibiotic treatment.

Reason for this study

Due to the limited number of patients with true penicillin allergy, sufficiently large prospective studies investigating the practicability, predictive value, and safety of the proposed de-labelling algorithm are missing to date. Until more robust data are available, well-studied patient series are a viable option to estimate the effectiveness and safety of such a de-labelling procedure.

Limitations of our study

Data were retrospectively extracted from patient records, resulting in a certain inhomogeneity. As a consequence, we limited ourselves to a descriptive presentation of data. In this series, no cases of a severe bullous skin reaction of the SJS-TEN spectrum were included.

Conclusions

-

(i)

Up to 10% of the population in Europe, North America, and Australia report penicillin allergy and most of these cases are not verified by allergy diagnostics. A label of penicillin allergy does not automatically require administration of an alternative antibiotic. Physicians should preferably estimate the probability of allergic hypersensitivity by standardized questioning.

-

(ii)

The algorithm applied in this study permits to detect evidence of allergic penicillin hypersensitivity with sufficient reliability, especially in cases of moderate to severe anaphylaxis.

-

(iii)

The algorithm-based recommendation to use an alternative antibiotic for patients reporting measles-like (maculopapular) exanthema should be critically reconsidered as (i) allergic hypersensitivity could be excluded by allergy testing in a significant number of cases, and (ii) measles-like exanthema is not a severe drug reaction to be avoided at all costs.

-

(iv)

Prospective studies of a sufficient size will be required to confirm the efficacy and safety of the proposed algorithm. Until more robust data are available, use of the algorithm should be confined to inpatients subsequently taking or receiving the penicillin or cephalosporin under direct medical supervision.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable (this is a retrospective data evaluation).

Abbreviations

- DRESS:

-

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

- FDE:

-

Fixed drug eruption

- SDRIFE:

-

Symmetrical drug related intertriginous and flexural exanthema

References

Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ. Antibiotic allergy. Lancet. 2019;393:183–98.

Macy E. Penicillin and beta-lactam allergy: epidemiology and diagnosis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:476.

Trubiano JA, Chen C, Cheng AC, Grayson ML, Slavin MA, Thursky KA, et al. Antimicrobial allergy “labels” drive inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing: lessons for stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1715–22.

Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:790–6.

Li M, Krishna MT, Razaq S, Pillay D. A real-time prospective evaluation of clinical pharmaco-economic impact of diagnostic label of “penicillin allergy” in a UK teaching hospital. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:1088–92.

Chiriac AM, Wang Y, Schrijvers R, Bousquet PJ, Mura T, Molinari N, et al. Designing predictive models for beta-lactam allergy using the drug allergy and hypersensitivity database. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:139–48.

Siew LQC, Li PH, Watts TJ, Thomas I, Ue KL, Caballero MR, et al. Identifying low-risk beta-lactam allergy patients in a UK tertiary centre. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2173–81.

Ramsey A, Caubet JC, Blumenthal K. Risk stratification and prediction in beta-lactam allergic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2182–4.

Devchand M, Urbancic KF, Khumra S, Douglas AP, Smibert O, Cohen E, et al. Pathways to improved antibiotic allergy and antimicrobial stewardship practice: the validation of a beta-lactam antibiotic allergy assessment tool. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1063–5.

Trubiano JA, Vogrin S, Chua KYL, Bourke J, Yun J, Douglas A, et al. Development and validation of a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:745–52.

Krishna MT, Huissoon AP, Li M, Richter A, Pillay DG, Sambanthan D, et al. Enhancing antibiotic stewardship by tackling “spurious” penicillin allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:1362–73.

Chiriac AM, Banerji A, Gruchalla RS, Thong BYH, Wickner P, Mertes PM, et al. Controversies in drug allergy: drug allergy pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:46–60.

Mustafa SS, Conn K, Ramsey A. Comparing direct challenge to penicillin skin testing for the outpatient evaluation of penicillin allergy: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2163–70.

Trubiano J, Phillips E. Antimicrobial stewardship’s new weapon? A review of antibiotic allergy and pathways to ‘de-labeling.’ Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:526–37.

Blumenthal KG, Parker RA, Shenoy ES, Walensky RP. Improving clinical outcomes in patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and reported penicillin allergy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:741–9.

Brockow K, Ardern-Jones MR, Mockenhaupt M, Aberer W, Barbaud A, Caubet JC, et al. EAACI position paper on how to classify cutaneous manifestations of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2019;74:14–27.

Mirakian R, Leech SC, Krishna MT, Richter AG, Huber PA, Farooque S, et al. Management of allergy to penicillins and other beta-lactams. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:300–27.

Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321:188–99.

Schrüfer P, Brockow K, Stoevesandt J, Trautmann A. Predominant patterns of beta-lactam hypersensitivity in a single German Allergy Center: exanthem induced by aminopenicillins, anaphylaxis by cephalosporins. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2020;16:102.

Trautmann A, Seidl C, Stoevesandt J, Seitz CS. General anaesthesia-induced anaphylaxis: impact of allergy testing on subsequent anaesthesia. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:125–32.

Volcheck GW, Hepner DL. Identification and management of perioperative anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2134–42.

Brown SG. Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:371–6.

Reichel A, Röding K, Stoevesandt J, Trautmann A. De-labelling antibiotic allergy through five key questions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:532–5.

Wöhrl S, Ostermayer C, Sesztak-Greinecker G, Jarisch R, Hemmer W, Wantke F. Drug-specific history, skin and in vitro tests can reduce the need for drug provocation tests in betalactam-hypersensitivity. Allergol Int. 2021;70:244–51.

Solensky R, Jacobs J, Lester M, Lieberman P, McCafferty F, Nilsson T, et al. Penicillin allergy evaluation: a prospective, multicenter, open-label evaluation of a comprehensive penicillin skin test kit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1876–85.

King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:67–71.

Jones BM, Bland CM. Penicillin skin testing as an antimicrobial stewardship initiative. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:232–7.

Caubet JC, Kaiser L, Lemaitre B, Fellay B, Gervaix A, Eigenmann PA. The role of penicillin in benign skin rashes in childhood: a prospective study based on drug rechallenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:218–22.

Seitz CS, Bröcker EB, Trautmann A. Diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity in children and adolescents: discrepancy between physician-based assessment and results of testing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:405–10.

Atanaskovic-Markovic M, Gaeta F, Medjo B, Gavrovic-Jankulovic M, Cirkovic Velickovic T, Tmusic V, et al. Non-immediate hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics in children—our 10-year experience in allergy work-up. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:533–8.

Ricci G, Giannetti A, Belotti T, Dondi A, Bendandi B, Cipriani F, et al. Allergy is not the main trigger of urticaria in children referred to the emergency room. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1347–8.

Friedmann PS, Pickard C, Ardern-Jones M, Bircher AJ. Drug-induced exanthemata: a source of clinical and intellectual confusion. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:255–9.

Scherer K, Bircher AJ. Danger signs in drug hypersensitivity. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:681–9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Würzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We hereby certify that we have personally written 100% of the manuscript. All authors have actively contributed to the conception and design of the study, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. PS and AT initiated data evaluation; PS, AT, and JS analyzed and interpreted the data; AT and PS wrote the first draft of the article; PS, AT, and JS revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board of the University Hospital Würzburg consented to the retrospective review and publication of anonymized data.

Consent for publication

No similar data has been or will be published or submitted elsewhere while our manuscript is under consideration at Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Diagnosis and sensitization to different β-lactams in 205 patients with allergic hypersensitivity (data from allergist directed testing) (modified from [19]).

Additional file 2:

Two X Two table depicting results of allergy testing and outcome of the de-labelling algorithm in total 800 patients.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schrüfer, P., Stoevesandt, J. & Trautmann, A. Outcome of a de-labelling algorithm compared with results of penicillin (β-lactam) allergy testing. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 18, 26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-022-00659-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-022-00659-1