Abstract

Exposure to traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) has been implicated in asthma development, persistence, and exacerbation. This exposure is highly significant as large segments of the global population resides in zones that are most impacted by TRAP and schools are often located in high TRAP exposure areas. Recent findings shed new light on the epigenetic mechanisms by which exposure to traffic pollution may contribute to the development and persistence of asthma. In order to delineate TRAP induced effects on the epigenome, utilization of newly available innovative methods to assess and quantify traffic pollution will be needed to accurately quantify exposure. This review will summarize the most recent findings in each of these areas. Although there is considerable evidence that TRAP plays a role in asthma, heterogeneity in both the definitions of TRAP exposure and asthma outcomes has led to confusion in the field. Novel information regarding molecular characterization of asthma phenotypes, TRAP exposure assessment methods, and epigenetics are revolutionizing the field. Application of these new findings will accelerate the field and the development of new strategies for interventions to combat TRAP-induced asthma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A recent comprehensive and systematic review of worldwide traffic emissions and health science by a special panel convened by the Health Effects Institute (HEI) found sufficient evidence that exposure to traffic-related air pollutants (TRAP) causes asthma exacerbation in children [1] and more recent reports have corroborated this [2, 3]. Within the complex mixture of gaseous and particulate components of TRAP, diesel exhaust particles (DEP) are of particular concern with respect to health effects. DEP are estimated to contribute up to 90 % of the particulate matter (PM) derived from traffic sources, are primarily ultrafine in size (<100 nm), can be deposited in the nasal and peripheral airways, and have been shown to induce oxidative stress and airway hyper-responsiveness, enhance allergic responses and airway inflammation [4–6]. This exposure is highly significant because in large cities in North America, up to 45 % of the population resides in zones that are most impacted by TRAP [1] and over 30 % of schools are located in high TRAP exposure areas [7]. Similar trends have been reported globally [8, 9]. Evidence from our group and others suggests TRAP is also associated with reduced lung growth and the development of asthma, though recent studies have reported conflicting results [10–16]. These inconsistent findings may be due to a lack of knowledge regarding the mechanistic basis of TRAP health effects and the characteristics of those most susceptibility to the harmful effects of TRAP exposure. Recent studies have started to fill gaps in knowledge regarding the molecular mechanisms by which TRAP leads to adverse effects on allergic diseases such as asthma. These studies demonstrate that exposure to DEP induces changes in DNA methylation that may have long lasting effects on health and future health risk.

Epidemiology of the health impact of TRAP on allergic disease

The prevalence and incidence of allergic diseases, including asthma, have been increasing worldwide since the 1960s [17, 18]. While asthma prevalence has plateaued in developed countries, in developing countries where the prevalence was previously low, allergic diseases are on the rise [19]. Environmental changes are suspected to be the major driver of this increasing trend [20], with air pollution identified as an important exposure [21]. Motor vehicles produce a complex mixture of air pollutants including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter (PM) of varying size, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs—e.g. benzo(a)pyrene), volatile organic compounds (VOCs—e.g. benzene, acetaldehyde) and other hazardous air pollutants (HAPs). Collectively referred to as traffic-related air pollutants (TRAP), these are the primary source of intraurban variability in air pollutant concentrations [1].

There is sufficient evidence to suggest that TRAP can decrease lung function and trigger asthma exacerbation and hospitalizations [18, 22]. Recent large studies on TRAP and respiratory outcomes substantiate these conclusions. Findings from the University of Southern California’s Children’s Health Study (CHS), a cohort of 11,365 schoolchildren in 16 communities, indicate that exposure to higher local nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations and close residential proximity to freeway increase asthma prevalence [23]. Asthmatic children in the cohort that lived in communities with higher levels of NO2, PM10 and PM2.5 had increased chronic lower respiratory symptoms, phlegm, production, bronchitis, wheeze and medication use [23]. In Korea, children aged 6–14 (n = 5443) living within 200 m of a main road that was ≥254 m long had increased lifetime wheezing, lifetime asthma diagnosis and decreased lung function [24]. A meta-analysis of six cohorts in the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE) that included 23,704 adults found that exposure to higher NO2 increased the incidence of adult-onset asthma, although the results did not reach significance [25].

Birth cohort studies have evaluated the impact of TRAP on asthma development in children. In the Cincinnati Childhood Allergy and Air Pollution Study (CCAAPS) birth cohort, a child’s risk for persistent wheeze and asthma development varied depending on the timing and duration of TRAP exposure [26]. The TRAP exposure level at the child’s birth address was associated with wheezing [27–29] and recurrent night cough [30] in the first 3 years of life. Children exposed to high levels of TRAP at birth were nearly twice as likely to experience persistent wheezing at age seven; however, a longer duration of exposure to high levels of TRAP (beginning early in life and continuing through age seven) was the only time period of exposure related to asthma development [26].

The ESCAPE project is comprised of five birth cohort studies including 17,041 children. While these birth cohorts did not find any significant associations between six traffic-related pollution metrics and childhood asthma prevalence, the land-use regression (LUR) models used to estimate exposures were carried out as long as 15 years after the asthma outcomes were collected [14]. During this time, campaigns to reduce air pollution could have reduced exposure levels compared to those present when the asthma outcomes were collected.

In 2015, Bowatte et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of birth cohort studies to understand the association between early childhood TRAP and subsequent allergies, asthma and allergic sensitization [16]. While significant associations were observed between asthma incidence and PM2.5 and black carbon (BC), there was substantial heterogeneity observed (likely due to differences in study design, participants and exposure and outcome definitions) between the studies [16]. Nevertheless, their review highlights that traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) is associated with new onset of asthma throughout childhood, and the authors suggest that TRAP exposure may have an ongoing effect with a lag time of about 3 years [16].

Reduced lung function as a consequence of air pollution exposures is also a recognized risk factor for long-term respiratory effects. The ESCAPE Project found that estimated levels of NO and PM were associated with small but significant reductions in lung function in school children [31]. Most recently, the investigators from the Child Heart and Health Study in England (CHASE) evaluated the effects of air pollution on lung function in children both in their cohort and in a systematic review and meta-analysis that included the ESCAPE studies [32]. In CHASE, they observed that residential levels of oxides of nitrogen and PM showed inverse but non-significant association with both FEV1 and FVC [32]. When the CHASE results were included in a meta-analysis of published studies, a statistically significant association between NO2 and FEV1 was observed. The authors estimate that every 10 μg/m3 increase in NO2 is associated with a 0.7 % decrease in FEV1, which translates into a 7 % increase in the prevalence of children with abnormal lung function [32], which is a significant public health concern. Similar to the CHASE meta-analysis, in 1968 Latino and African-American children from the US and Puerto Rico, a 5 μg/m3 increase in average lifetime PM2.5 was associated with a 7.7 % decrease in FEV1 [33]. In children aged 10–18 participating in the University of Southern California CHS mentioned above, living within 500 m of a freeway was associated with a significant reduction in FEV1, FVC and maximal mid-expiratory flow rate compared to those living more than 1500 m away [23].

Collectively, there is considerable evidence that TRAP plays a role in the development, and/or symptoms of asthma. However, heterogeneity in both the definitions of TRAP exposure and asthma outcomes and unmeasured confounding limit the ability to draw firm conclusions from the data. As discussed in the Bowatte et al. meta-analyses, there is substantial variability in the exposure measurements across TRAP-related studies. Land use regression (LUR) models are among the most common methods to assess TRAP exposures [16]. Other methods include passive samplers, central monitoring stations and proximity to major roads. The most frequent markers of pollutants include PM, oxides of nitrogen, carbon monoxide and ozone. PM may be further reported as BC, PM10, or PM2.5. While this vast variation in the definition of TRAP exposure limit the ability to conduct sound meta-analyses, it highlights the importance of appropriate exposure assessment, as discussed below.

The other central challenge is the vast heterogeneity of asthma. The term “asthma” encompasses a number of distinct phenotypes of asthma, which have different molecular signatures. These asthma “endotypes” are subsets of disease defined by a distinct functional or pathobiological mechanisms [34]. The linkage to pathogenic mechanisms makes recognition of endotypes especially valuable, as knowledge of pathogenic mechanisms of specific variants of asthma may serve as a more precise guide to treatment. TRAP-induced asthma is a distinct phenotype of asthma, which was recently shown by our group to be characterized by increased levels of serum IL-17A in children and increased CD4+IL13+IL17+ double-producing T effector memory cells in mice [6, 35]. Thus, studies of the health effects of TRAP exposure need to carefully define and characterize both the exposure variable and the health outcome.

Assessment of TRAP exposure

Given the increasingly evident health impact of TRAP, methodologies to accurately assess exposure are needed. While TRAP affects air quality on urban and regional scales, their impact is greatest on a local scale, particularly near roadways, as their concentrations are significantly elevated within approximately 300–500 m of their source [36]. Further influencing individuals’ TRAP exposure is its temporal variability combined with complex and variable personal behavior including time spent indoors/outdoors [37]. In order to meet the intrinsic challenge of accurately assessing TRAP exposure for epidemiologic studies both modeling and personal measurement approaches have been utilized. Because particulate matter (PM) is a complex mixture of chemical and elemental constituents, recent studies have focused on assessing exposure and associating health effects with specific elemental PM components, rather than the more traditionally used total PM mass. Most notably, the large ESCAPE project has developed land use regression models for particle composition in twenty study areas in Europe [38]. Accurate and precise models were built for individual components and the group used these to associate exposure to PM2.5 nickel and sulfur with decreased lung function in five cohorts of children [39]. Furthermore, they found that long term exposure to PM2.5 copper and PM10 iron was associated with increased levels of inflammatory blood markers [38].

While regulatory air monitoring provides valuable data to link regional and temporal variability of air pollutants to population-level health outcomes [40–43], these networks are unable to capture the high spatial variability of TRAP concentrations within an urban area. Measuring proximity (i.e. distance) to major roadways is a straightforward approach to estimate TRAP exposure, though this method does not account for traffic density and other geographic and land-use characteristics which impact TRAP concentrations [44]. Dispersion models have also been used to assess exposure to TRAP, but this approach has been limited to a small number of locales with available emissions and meteorology data required for this approach [10, 45, 46].

The most frequently used method to estimate TRAP exposure in epidemiologic studies is land use regression (LUR) modeling [44, 47–49]. In the most straightforward LUR approach, a single pollutant from the TRAP mixture is measured at multiple stationary sites within a defined study region and characteristics of the area surrounding each sampling site (e.g. elevation, nearby roads, traffic) are used as predictors of the measured concentrations in a linear model. The resultant LUR model is then applied to estimate pollutant concentrations at non-sampled locations including schools and homes where significant geographic predictor variables can be determined [14, 15, 44, 48, 50–57]. Recently, research groups have created land use models to predict the concentration of individual components of PM in more urban environments [58]. The temporal variability of TRAP concentrations have also been incorporated into LUR models through the addition of mobile or continuous monitoring allowing for short-term and daily estimates of TRAP exposure for study participants [52, 59–62]. LUR models have also been shown to accurately capture the spatial variability in pollutant concentrations over a period of 7 or more years [63, 64]. New data inputs for LUR models, including satellite-derived pollutant measurements [65, 66] and the development of hybrid models combining LUR with Bayesian Maximum Entropy have also improved the accuracy of TRAP exposure assessment [67, 68]. In studies with available participant-reported time spent in locations outside the home, LUR models have been used to derive time-weighted estimates of exposure based on location [48]. More recent application of this time-weighted approach have utilized smartphones and GPS-derived location data to improve estimates of TRAP exposure by combining LUR or other modeled TRAP estimates with individuals’ location through space and time [69]. External model validation is also key to accurate exposure assessment. Researchers recently found that models developed for specific neighborhoods were not generalizable to other neighborhoods, but that a general model that was locally calibrated performed similarly to neighborhood-specific models [70].

Despite advances in modeling TRAP and the incorporation of GPS to improve estimates of individual-level exposure, personal monitoring remains the ‘gold-standard’ for TRAP exposure assessment. The use of mobile monitoring has increased in popularity, in part due to its ability to cover a higher spatial resolution as compared to stationary monitoring. Land use regression models have been developed using data from mobile laboratories [71] as well as cars and bikes [72], allowing for resolutions up to 20 m. Although the increased resolution is an advantage of using mobile monitoring to collect air pollution measurements, it requires multiple repeated measurements to precisely predict exposure.

Mechanistic insights into TRAP effects on the epigenome and the pathogenesis of asthma

Although there is strong evidence that TRAP exposure contributes to childhood asthma [1, 10, 11, 29], the mechanistic basis of TRAP effects on asthma has been elusive. The epigenetic, molecular, and cellular pathways triggered by exposure to TRAP and their impact on allergen-induced immune responses have been studied in human studies as well as in reductionist models in vitro and in animal models in vivo.

The basics of epigenetics

The concept of epigenetics keeps revolving since Waddington first coined the word to describe mechanisms that regulate gene expression and contribute to development [73]. A modern definition of an epigenetic trait is a stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence [74]. To date, epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modification, histone variants, nucleosome positioning, non-coding RNA and other newly discovered phenomenon such as RNA methylation. Together, these epigenetic mechanisms regulate the gene expression programs of a cell by being responsive to changes in the environment of a cell, including all the developmental signals and environmental cues that lead to diseases, which is particularly evident during cellular differentiation and cancer development [75–77]. A compelling hypothesis is that environmental cues associated with diseases might initiate or influence the epigenetic processes of host cells, leading to epigenetic reprogramming of host cells to favor their pathogenic function and contributing to the development of the disease. DNA methylation is the first epigenetic mechanism recognized and most extensively studied in human populations. Thus, the main focus of this part of the review is on DNA methylation, its association with air pollution and asthma, and its impact on the association between air pollution with asthma.

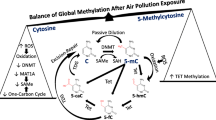

DNA methylation is the chemical modification of cytosine by covalently adding a methyl group to its 5′ carbon (5-methylcytosine, or 5mC), which is mostly found in the context of CpG dinucleotide. CpG islands (defined as regions of more than 200 bases with a G + C content of at least 50 % and a ratio of observed to an expected frequency of at least 0.6) are often found at functionally relevant genomic elements, such as promoters and enhancers, indicating their important role in gene regulation. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling by next-generation sequencing in several species has demonstrated that DNA methylation at the promoter and at the 3′ end of a gene is negatively associated with gene expression levels, whereas whole gene body methylation seems to be positively associated with gene expression levels [78, 79]. In mammalian cells, DNA methylation is maintained through the coordinated actions of DNA methyl-transferases (DNMTs), which catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to the carbon 5′ position of cytosine (Fig. 1). Replication of symmetrically methylated CpGs leads to hemi-methylated parent-daughter duplexes, which will be methylated by DNMT1/UHRF1 complex [80, 81]. Non-CpG methylation occurs primarily in pluripotent stem cells and neuron cells [82, 83], and is maintained by two de novo methylases, DNMT3a and 3b [83, 84]. Recently TET proteins (ten-eleven translocation family) were identified as dioxygenases that utilize two key factors Fe(II) and 2-oxyglutarate (2-OG), to oxidize the methyl group of 5mC to hydroxylmethyl, formyl, or carboxyl groups [85–89] (Fig. 1). The resulting oxi-mC intermediates (5hmC, 5fmC and 5caC) can be restored to C by active or passive mechanisms [88, 89], resulting in DNA demethylation (Fig. 1).

DNA methylation and demethylation in mammals. DNMTs methylate cytosine C to 5-methylcytosine (5mC) by transferring the methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to cytosine. TET enzymes oxidize 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) (together, oxi-mC). Further, oxi-mC can be restored to C through the thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG)-mediated base excision repair (BER) of 5fC:G and 5caC:G base pairs and replication-dependent passive demethylation

Many cellular differentiation processes, including immune cell differentiation, are accompanied by dynamic changes in DNA methylation and other epigenetic changes, which often occur at key transcription factors sites and at genomic locations encoding functional molecules such as cytokines to control their lineage commitment [76, 90–92]. Protein components in epigenetic machinery such as DNMTs, TETs and DNA methyl-group binding proteins, often bind to these cytokine signature gene loci through interaction with key transcriptional factors, setting up local epigenomic structure and controlling their expression [92]. In addition, environmental cues including air pollution can directly regulate the expression levels of DNMTs and TETs [93–96], or accumulation of these enzymes at targeted genes [97, 98], therefore modify the epigenomic landscape of key genes involved in asthma pathogenesis.

DNA methylation and asthma

Epigenomic regulation of T cell differentiation plays an important role in the process of allergic sensitization [99–101], including T helper cell differentiation (Th1, Th2 and Th17) and the establishment of regulatory T cell phenotype (Treg). Activation of the T helper 2 (Th2) type cytokine profile is a hallmark of experimental asthma. Epigenetic remodeling including DNA methylation changes and histone modifications has been shown to influence Th2 polarization and associated cytokines and chemokines involved in the development of asthma [102–104, 106]. Further, pharmacological modification of IFNγ methylation in T cells modifies asthma phenotypes in animal models [107]. Tregs also play an essential role in allergic responses in asthma [108] and FOXP3 is the master regulator of Tregs. The regulation of FOXP3 expression by methylation at its proximal promoter and an intronic regulatory element is well-established and studies from twins discordant for asthma indicate that this mechanism is important for asthma development [99, 109].

Although asthma has long been characterized as a disease of dysregulated TH2 immune responses to environmental allergens, accumulating evidence suggests a role for TH17 cells, especially severe steroid resistant asthma. Serum IL-17A is significantly higher in severe asthmatics compared to mild asthmatics or controls in adults and children [110–112]. Recent studies have demonstrated that dual-positive TH2/TH17 cells and IL-17A were present at a higher frequency in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from steroid resistant asthmatic patients [113]. These TH2/TH17 cells were resistant to dexamethasone-induced cell death and the TH2/TH17 predominant subgroup of patients manifested the most severe form of asthma [113]. As an important player in asthma development, especially air pollution-related asthma [6], the epigenetic regulation of Th17 cells is not well understood. Recently it has been shown that the promoter of IL17a and intron 2 of Rorα (IL17 associated transcriptional factor) were demethylated in ex vivo isolated murine Th17 cells and in murine Th17 cells generated invitro compared to naïve T cells and other T helper cells [114]. This is consistent with a previous report highlighting the epigenetic regulation of Il17a and IL17f expression by promoter DNA methylation and histone modifications in in vitro generated murine Th17 cells [115].

In addition to genes implicated in T cell function, which have been relatively well studied, association studies in human populations identified epigenetic variations in other genes important for asthma, including those involved in immune responses, nitric oxide synthesis, lipidomics, and pharmacologic receptors [99]. In support of these previous findings, a recent report using a genome-wide approach identified an IL13-induced DNA methylation signature in adult asthmatic airways, which contains two co-methylation modules related to asthma severity and eosinophilia respectively [116]. Using the same platform, another study compared blood DNA methylation levels between 97 controls and 97 inner city asthmatic patients and identified 81 differentially methylated CpG sites [117]. Validated CpG sites are located at RUNX3 (related to T cell maturation), IL4 (related to Th2 function), and catalase (related to oxidative stress). CpG sites associated with serum IgE among asthmatics were also discovered in this study. An epigenome-wide association study also identified and validated 36 CpG sites whose methylation levels in blood DNA are significantly associated with serum IgE level (FDR < 10−4) [118]. Importantly, the top three CpG sites account for 13 % of IgE variation, which is tenfold higher than that derived from large single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genome-wide studies. This implies a significant role for epigenome in asthma and underscores that the epigenome may be a rich source of novel biomarkers for asthma and potentially new targets for asthma therapy. Recent evidence from our group associated lower TET1 promoter methylation and higher 5hmC levels in airway epithelial cells with childhood asthma, uncovering a novel role of TET1 and DNA demethylation in asthma development [95]. In addition, researchers also started to look at DNAm markers for asthma that develops in childhood and persists into early adulthood [119] and markers for temporal asthma transition [120]. Despite these investigations, DNAm variations consistently associated with asthma are rarely found, possibly due to differences between cohorts, definition of asthma phenotypes, and from which tissue DNAm is measured. Disease-epigenetic variation is often tissue-specific, which should be accounted for when interpreting the results. How this should be considered in epigenomic epidemiologic studies has been discussed in other reviews [121].

Studies of DNA methylation are often coupled with gene expression studies and genetic variation studies, as DNA methylation can regulate gene expression [122] and SNPs also modify DNA methylation [123, 124]. Morales et al. demonstrated an interaction between SNPs within ALOX12 and a nearby DNA methylation variation that is significantly associated with childhood wheezing in three cohorts [125]. Interestingly, this interaction is most evident for those SNPs tagged by rs312466, and rs312466 is ~300 away from the interacting CpG site, indicating an in cis interaction. In the Swedish birth-cohort BAMSE, Acevedo and colleagues studied the association of childhood asthma with SNPs, regional DNA methylation, and gene expression at the GSDMB/ORMDL3 locus located at 17q21, a well-studied asthma-susceptibility locus found in ethically diverse populations [126]. They found that 3 SNPs that either created or removed CpG sites altered DNA methylation in cis and were associated with asthma. Methylation at these SNP-CpG sites was correlated with ORMDL3 expression and associated with methylation levels at other CpG sites in this locus, including ones located in the ORMDL3 promoter. They also found that the methylation levels in the ORMDL3 promoter was higher compared to controls, and correlated with ORMDL3 expression in blood leukocytes from asthmatic children. Together, these data suggest interactions among CpG sites and between CpG sites and SNPs within this locus in asthma. Future well-designed, integrative genome- and epigenome-wide associations studies are needed to examine the interplay between genetic and epigenetic factors and how these interactions contribute to asthma in a cell type-specific manner.

Air pollution and DNA methylation

The epigenome is postulated to be a mechanistic bridge between air pollution and the development of asthma, possibly via mediating gene-environment interactions [99, 127]. Indeed, combined inhaled diesel exhaust particles and allergen exposure in mice lead to changes in promoter methylation of the asthma related gene IL4, and methylation levels are correlated with serum IgE changes [128]. These findings are consistent with numerous studies that have demonstrated that exposure to either particulate matter or DEP exacerbates TH2 responses. One recent study using co-cultures of OVA transgenic CD4+ T cells and bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDC) pre-exposed to OVA with or without TRAP, demonstrated increased IFNγ, IL4, IL13, and IL17 levels in culture supernatants of OVA + TRAP exposed BMDC compared to BMDC exposed to OVA alone [129].

A growing body of literature has identified DNA methylation variations associated with different types of air pollution in human populations, including TRAP [127, 130]. TRAP is a mixture of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, PM, PAH, VOCs and other HAPs. Among these components, PM2.5 from various sources has been associated with DNA methylation changes [130]. However, these studies are often inconsistent, possibly due to the differences in exposure measurement and different relative amounts of the TRAP components within the estimate; therefore, the impact of TRAP on repeat element methylation or global DNA methylation remains uncertain. One recent study evaluated the in vitro epigenotoxicity of six different types of ambient air PM [131] including soil dust, road dust, agricultural dust, biomass burning, traffic exhausts, and pollen. Indeed, these different types of PMs have very different, sometimes opposite, effects on the expression and enzymatic activity of DNMTs and the methylation of repetitive elements. Further, such impact is time-specific and dose-dependent.

Using a candidate gene approach, multiple cohort studies have consistently linked DNA methylation levels in the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene (iNOS) with exposure to particulate matter [132–137]. iNOS and other components in the nitric oxide synthase pathway are responsible for nitric oxide production, and children with asthma and allergic airway diseases have measurably higher fractional concentration of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) [138, 139]. Interestingly, an interaction between genetic variants, DNA methylation variation within iNOS, and PM exposure has been noted [137]. Other genes whose methylation levels in saliva DNA have been associated with ambient air pollution have also been implicated in asthma. A recent study identified an association between methylation of 31 genes and exposure to BC utilizing a pathway-based approach [140]. The genes included HLA-DOB (MHCII), FCER1A and FECR1G (IgE receptor), IL9, and MBP (eosinophil granule major basic protein), which are related to the Th2/B cell signaling pathway, eosinophils, and airway inflammation. Increased exposure to ambient air pollution was also associated with hypermethylation of FOXP3, which coincided with impaired Treg function and increased asthma morbidity [141]. Hypermethylation of IFN-γ in effector T cells was associated with increased exposure to ambient air pollution in the same cohort [142] and was further supported by observations from the Normative Aging Study [143]. Research from our group also uncovered the association of saliva FOXP3 methylation with TRAP exposure during the 1st year of life and persistent wheezing and asthma diagnosis at age 7 in the CCAAPS cohort [144], which implicates the epigenome as a mediator of the impact of early life TRAP exposure on later asthma risk. Further work using the fast developing genome-wide approaches to identify TRAP-associated DNA methylation changes in relevant tissues using a longitudinal design are needed.

Recently we found that TET1 promoter methylation is associated with both TRAP exposure and asthma prevalence in children [95]. Exposure of airway epithelial cells to DEP altered the expression of TET1, and resulted in changes in global 5hmC [95]. Further, exposure to PM10 was associated with higher global 5hmC levels over time, but not with global 5mC levels [145]. In the same cohort, PM exposure was associated with hypomethylation of selected tandem repeats, such as NBL2 and SATa [146]. Taken together, these data support a role for 5hmC and TET1 in response to TRAP exposure and highlight the need to differentiate 5hmC and 5mC in future environmental epigenetic studies.

To directly investigate the short-term DNA methylation changes induced by exposure to TRAP in humans, controlled exposure studies have been performed in adults [147, 148]. A cross-over study in 15 healthy adults showed that exposure to concentrated ambient particles (CAPs) for 130 min lowered methylation levels at specific loci [147]: fine CAPs exposure lowered Alu methylation, while coarse CAPs exposure lowered TLR4 methylation. In another cross over study [148], sixteen non-asthmatic adults were exposed to diesel exhaust (300 μg/m3 PM2.5) for 2 h on two separate occasions at least 2 weeks apart. RNA samples isolated from their peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were subjected to the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array to identify genome-wide changes associated with DEP exposure at 6 h or 30 h after the second exposure. Genes encoding protein kinases and other proteins in the NF-kB pathways become less methylated after the exposure. In a more recent study [149], Clifford et al. conducted a randomized, crossover-controlled exposure study in which 17 adults were exposed to filtered air or diesel exhaust (DE, 300 μg/m3 PM2.5) followed by saline via segmental allergen challenge. Genome-wide DNAm studies using bronchial epithelial cells collected 48 h after the last challenge identified changes at 6 CpG sites in response to DE, 7 sites in response to co-exposure (DE and allergen), while allergen alone didn’t cause any significant differences. Interestingly, allergen challenge 4 weeks after DE exposure induced DNAm changes at more CpG sites (75 sites at p < 0.05, difference in β > 0.10) suggesting that DE exposure may have long lasting effects on epigenetic responses to subsequent exposures.

Exposure to other components in TRAP, specially PAH, has also been associated with DNA methylation changes [130]. The epigenetic effects of PAH can begin in utero, which may lead to long-term health problems. Maternal exposure to PAH is associated with DNA methylation changes in the acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3 (ACSL3) gene in cord blood cells of children and is also associated with higher risk of developing asthma [150]. Maternal PAH exposure has also been linked to increased methylation of IFN-γ promoter in cord white blood cells [151]. Collectively, these data support the notion that methylation modifications can link in utero exposure with asthma development [152–154]. Similarly to PM exposure, exposure to ambient PAH can be associated with impaired Treg function and increased methylation of FOXP3 [155].

How TRAP, including DEP and PAH, modifies the epigenome remains unclear. One hypothesis is that the epigenetic changes are mediated via the AhR, which subsequently regulates the expression and function of the epigenetic machinery that can activate/repress target genes related to inflammation and immune responses (Fig. 2). It has been shown that the expression of DNMTs and TETs is altered in the lungs of asthmatics [93–95]. A few recent reports have demonstrated the regulatory role of TET1/2/3 in hematopoiesis [156], B cell lineage specification [157] and Treg differentiation [158–160], which are all involved in asthma development. Exposure to air pollution can regulate the expression levels of these proteins in airway epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages [95, 131] (Fig. 2). Air pollution may also modify the accumulation of epigenetic enzymes at genetic loci involved in asthma pathogenesis [97, 98], thereby modifying the local epigenomic landscape of these genes and contributing to asthma. Expression of DNMTs and TET1 can both be regulated in a HIF1α-dependent matter under hypoxia conditions [161, 162]. In addition, it is reported that oxidative stress and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can regulate HIF1α transcription in humans [163]. Since the HIF1α and AhR pathways may intersect [164], it is plausible that the effects of DEP are partially mediated through interactions between AhR, HIF1α, DNMTs and TETs (Fig. 2). Futures studies elucidating the interactions between AhR signaling and the epigenetic machinery are needed to pinpoint the mechanisms by which TRAP contribute to asthma.

Epigenetic mechanisms mediate DEP effects on asthma pathogenesis. Lung epithelial cells recognize polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons present in diesel exhaust particles (DEPs) via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), promoting cytochrome P450 family 1 A1 (CYP1A1)-mediated and iNOS-mediated detoxification through altering methylation. Failure to detoxify results in oxidative stress, which may upregulate TETs and downregulate DNMTs through the crosstalk between AhR and HIF1-α and directly lead to secretion of chemokines (eosinophils/neutrophils) and cytokines involved in TH17 and TH2 differentiation (TSLP), Treg differentiation and B cell function, all contributing to airway inflammation. The secretion of these chemokines and cytokines can also be triggered by repair cytokines (amphiregulin, TGFα) signaling through the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and NF-κB, which can be augmented by demethylation and upregulation through TET proteins and DNMTs. DEP promotes allergic airway inflammation by upregulating the expression of the Jagged1/Notch1 pathway in dendritic cells (DC) in an AhR dependent manner in concert with allergens. DEP may also regulate DNMT and TET expression in dendritic cells and macrophages through the AhR pathway, enhancing airway inflammation in presence of allergens. DEP diesel exhaust particle; OVA ovalbumin; TSLP thymic stromal lymphopoietin

The impact of early life TRAP exposure

The timing and duration of traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) exposure may be important for childhood wheezing and asthma development. High TRAP exposure at birth was significantly associated with wheezing phenotypes in a birth cohort, but only long-term exposure to high levels of TRAP throughout childhood was associated with asthma development [26]. Indeed, in the Cincinnati Childhood Allergy and Air Pollution Study (CCAAPS) birth cohort, early TRAP exposure was associated with persistent wheeze while early and sustained exposure to TRAP was associated with asthma development [26]. As discussed above, saliva FOXP3 methylation was found to be associated with TRAP exposure during the 1st year of life and persistent wheezing and asthma diagnosis at age 7 in the CCAAPS cohort [144], suggesting that the epigenome may contribute to the impact of early life TRAP exposure on later asthma risk.

Prenatal TRAP exposure has been linked to asthma as well [165–168]. Mothers who lived near highways during pregnancy are more likely to have children with asthma [166]. Prenatal exposure to PAHs is associated with increased risk of allergic sensitization and early childhood wheeze [165, 168]. A limited number of mechanistic studies have assessed the impact of in utero TRAP exposure on the development of allergic disorders. In one recent study, offspring of mice exposed to DEP were hypersensitive to OVA and developed increased OVA sensitization, airway inflammation, Th2/Th17 responses, and AHR compared to offspring with no prior in utero DEP exposure [169]. Further, prenatal DEP exposure induced expression of genes downstream of AhR and this upregulation persisted 1 month after birth, even though mice were no longer exposed to DEP. Thus, in utero DEP exposure appears to result in a primed state where the neonate is hypersensitive to subsequent allergen exposure. In mice exposed to ambient particulate air pollution near steel mills and major high ways, there is significant, persistent sperm DNA hypomethylation [170], suggesting a transgenerational effect of TRAP exposure. Thus, the epigenetic changes induced by TRAP may have very long lasting effects. While the epigenetic mediation of the trans-generational impact of numerous exposures (endocrine disruptors, high fat diets) is being actively explored; the evidence for the epigenetic mediation of trans-generational effects of TRAP is lacking and in need of better investigation.

Conclusion

As discussed above, there is considerable evidence that exposure to TRAP is associated with childhood asthma development, symptoms, and exacerbations. Herein, we have reviewed the recent findings regarding the epigenetic mechanisms by which TRAP exposure mediates its negative health effects. These findings have identified potential biomarkers that could enable rapid and reliable identification of individuals at-risk due to high exposure in the future. Further, new methodologies for quantification of TRAP will enable accurate assessment of exposure in real time such that interventions could be designed and implemented early in the course of exposure in vulnerable populations. Additional studies are needed to fill the remaining gaps including more careful characterization of the epigenetic modifications and the upstream/downstream pathways, the study of interactions between genetic and epigenetic variations, the impact of the timing, load, and duration of TRAP exposure on the durability of the epigenetic modifications, and translation of these findings to clinical applications.

References

HEI Panel on the Health Effects of Traffic-Related Air Pollution. Traffic-related air pollution: a critical review of the literature on emissions, exposure, and health effects. Boston: Health Effects Institute; 2010.

Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1581–92.

Gowers AM, Cullinan P, Ayres JG, Anderson HR, Strachan DP, Holgate ST, et al. Does outdoor air pollution induce new cases of asthma? Biological plausibility and evidence; a review. Respirology. 2012;17(6):887–98.

Acciani TH, Brandt EB, Khurana Hershey GK, Le Cras TD. Diesel exhaust particle exposure increases severity of allergic asthma in young mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(12):1406–18.

Takahashi G, Tanaka H, Wakahara K, Nasu R, Hashimoto M, Miyoshi K, et al. Effect of diesel exhaust particles on house dust mite-induced airway eosinophilic inflammation and remodeling in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112(2):192–202.

Brandt EB, Kovacic MB, Lee GB, Gibson AM, Acciani TH, Le Cras TD, et al. Diesel exhaust particle induction of IL-17A contributes to severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1194–2042.

Appatova AS, Ryan PH, LeMasters GK, Grinshpun SA. Proximal exposure of public schools and students to major roadways: a nationwide US survey. J Environ Plann Man. 2008;51(5):631–46.

Amram O, Abernethy R, Brauer M, Davies H, Allen RW. Proximity of public elementary schools to major roads in Canadian urban areas. Int J Health Geogr. 2011;10:68.

Hystad P, Demers PA, Johnson KC, Brook J, van Donkelaar A, Lamsal L, et al. Spatiotemporal air pollution exposure assessment for a Canadian population-based lung cancer case-control study. Environ Health. 2012;11:22.

McConnell R, Islam T, Shankardass K, Jerrett M, Lurmann F, Gilliland F, et al. Childhood incident asthma and traffic-related air pollution at home and school. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(7):1021–6.

Jerrett M, Shankardass K, Berhane K, Gauderman WJ, Kunzli N, Avol E, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and asthma onset in children: a prospective cohort study with individual exposure measurement. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(10):1433–8.

Gauderman WJ, Vora H, McConnell R, Berhane K, Gilliland F, Thomas D, et al. Effect of exposure to traffic on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age: a cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369(9561):571–7.

Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Gilliland F, Vora H, Thomas D, Berhane K, et al. The effect of air pollution on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1057–67.

Molter A, Simpson A, Berdel D, Brunekreef B, Custovic A, Cyrys J, et al. A multicentre study of air pollution exposure and childhood asthma prevalence: the ESCAPE project. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(3):610–24.

Clark NA, Demers PA, Karr CJ, Koehoorn M, Lencar C, Tamburic L, et al. Effect of early life exposure to air pollution on development of childhood asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(2):284–90.

Bowatte G, Lodge C, Lowe AJ, Erbas B, Perret J, Abramson MJ, et al. The influence of childhood traffic-related air pollution exposure on asthma, allergy and sensitization: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of birth cohort studies. Allergy. 2015;70(3):245–56.

Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):733–43.

Eder W, Ege MJ, von Mutius E. The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(21):2226–35.

Hatzler L, Hofmaier S, Papadopoulos NG. Allergic airway diseases in childhood - marching from epidemiology to novel concepts of prevention. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(7):616–22.

Gehring U, Cyrys J, Sedlmeir G, Brunekreef B, Bellander T, Fischer P, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and respiratory health during the first 2 years of life. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(4):690–8.

Takizawa H. Impact of air pollution on allergic diseases. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26(3):262–73.

Tatum AJ, Shapiro GG. The effects of outdoor air pollution and tobacco smoke on asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25(1):15–30.

Chen Z, Salam MT, Eckel SP, Breton CV, Gilliland FD. Chronic effects of air pollution on respiratory health in Southern California children: findings from the Southern California Children’s Health Study. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(1):46–58.

Jung DY, Leem JH, Kim HC, Kim JH, Hwang SS, Lee JY, et al. Effect of traffic-related air pollution on allergic disease: results of the children’s health and environmental research. Allergy Asthma Immun Res. 2015;7(4):359–66.

Jacquemin B, Siroux V, Sanchez M, Carsin AE, Schikowski T, Adam M, et al. Ambient air pollution and adult asthma incidence in six european cohorts (ESCAPE). Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(6):613–21.

Brunst KJ, Ryan PH, Brokamp C, Bernstein D, Reponen T, Lockey J, et al. Timing and duration of traffic-related air pollution exposure and the risk for childhood wheeze and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(4):421–7.

Ryan PH, Bernstein DI, Lockey J, Reponen T, Levin L, Grinshpun S, et al. Exposure to traffic-related particles and endotoxin during infancy is associated with wheezing at age 3 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1068–75.

Ryan PH, LeMasters G, Biagini J, Bernstein D, Grinshpun SA, Shukla R, et al. Is it traffic type, volume, or distance? Wheezing in infants living near truck and bus traffic. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(2):279–84.

Ryan PH, Levin L, Bernstein DI, Burkle J, Grinshpun SA, Lockey JE, et al. Early life exposure to traffic pollutants and wheezing throughout childhood: the cincinnati childhood allergy and air pollutions study (CCAAPS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:A3748.

Sucharew H, Ryan PH, Bernstein D, Succop P, Khurana Hershey GK, Lockey J, et al. Exposure to traffic exhaust and night cough during early childhood: the CCAAPS birth cohort. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(2 Pt 1):253–9.

Gehring U, Gruzieva O, Agius RM, Beelen R, Custovic A, Cyrys J, et al. Air pollution exposure and lung function in children: the ESCAPE project. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(11–12):1357–64.

Barone-Adesi F, Dent JE, Dajnak D, Beevers S, Anderson HR, Kelly FJ, et al. Long-term exposure to primary traffic pollutants and lung function in children: cross-sectional study and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142565.

Neophytou AM, White MJ, Oh SS, Thakur N, Galanter JM, Nishimura KK, et al. Air pollution and lung function in minority youth with asthma in the GALA II & SAGE II studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1271–80.

Lotvall J, Akdis CA, Bacharier LB, Bjermer L, Casale TB, Custovic A, et al. Asthma endotypes: a new approach to classification of disease entities within the asthma syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(2):355–60.

Brandt EB, Biagini Myers JM, Acciani TH, Ryan PH, Sivaprasad U, Ruff B, et al. Exposure to allergen and diesel exhaust particles potentiates secondary allergen-specific memory responses, promoting asthma susceptibility. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(2):295–303.

Karner AA, Eisinger DS, Niemeier DA. Near-roadway air quality: synthesizing the findings from real-world data. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(14):5334–44.

Brauer M. How much, how long, what, and where: air pollution exposure assessment for epidemiologic studies of respiratory disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2010;7(2):111–5.

de Hoogh K, Wang M, Adam M, Badaloni C, Beelen R, Birk M, et al. Development of land use regression models for particle composition in twenty study areas in europe. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(11):5778–86.

Eeftens M, Hoek G, Gruzieva O, Molter A, Agius R, Beelen R, et al. Elemental composition of particulate matter and the association with lung function. Epidemiology. 2014;25(5):648–57.

Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(24):1753–9.

Bell ML, Ebisu K, Peng RD, Samet JM, Dominici F. Hospital admissions and chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(12):1115–20.

Dominici F, Peng RD, Bell ML, Pham L, McDermott A, Zeger SL, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1127–34.

Peng RD, Bell ML, Geyh AS, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM, et al. Emergency admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and the chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(6):957–63.

Ryan PH, Lemasters GK, Biswas P, Levin L, Hu S, Lindsey M, et al. A comparison of proximity and land use regression traffic exposure models and wheezing in infants. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(2):278–84.

Batterman S, Ganguly R, Isakov V, Burke J, Arunachalam S, Snyder M, et al. Dispersion modeling of traffic-related air pollutant exposures and health effects among children with asthma in Detroit, Michigan. Transp Res Rec. 2014;2452:105–12.

Oftedal B, Nystad W, Brunekreef B, Nafstad P. Long-term traffic-related exposures and asthma onset in schoolchildren in Oslo, Norway. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(5):839–44.

Ryan PH, LeMasters GK. A review of land-use regression models for characterizing intraurban air pollution exposure. Inhalation Toxicol. 2007;19(1):127–33.

Ryan PH, Lemasters GK, Levin L, Burkle J, Biswas P, Hu S, et al. A land-use regression model for estimating microenvironmental diesel exposure given multiple addresses from birth through childhood. The Sci Total Environ. 2008;404(1):139–47.

Hoek G, Beelen R, de Hoogh K, Vienneau D, Gulliver J, Fischer P, et al. A review of land-use regression models to assess spatial variation of outdoor air pollution. Atmos Environ. 2008;42(33):7561–78.

Briggs DJ, de Hoogh C, Gulliver J, Wills J, Elliott P, Kingham S, et al. A regression-based method for mapping traffic-related air pollution: application and testing in four contrasting urban environments. The Sci Total Environ. 2000;253(1–3):151–67.

Clougherty JE, Wright RJ, Baxter LK, Levy JI. Land use regression modeling of intra-urban residential variability in multiple traffic-related air pollutants. Environ Health. 2008;7(1):17.

Dons E, Van Poppel M, Int Panis L, De Prins S, Berghmans P, Koppen G, et al. Land use regression models as a tool for short, medium and long term exposure to traffic related air pollution. Sci Total Environ. 2014;476:378–86.

Gehring U, Wijga AH, Brauer M, Fischer P, de Jongste JC, Kerkhof M, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and the development of asthma and allergies during the first 8 years of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):596–603.

Henderson SB, Beckerman B, Jerrett M, Brauer M. Application of land use regression to estimate long-term concentrations of traffic-related nitrogen oxides and fine particulate matter. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41(7):2422–8.

Hoek G, Beelen R, Kos G, Dijkema M, Zee SC, Fischer PH, et al. Land use regression model for ultrafine particles in Amsterdam. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(2):622–8.

Ross Z, English PB, Scalf R, Gunier R, Smorodinsky S, Wall S, et al. Nitrogen dioxide prediction in Southern California using land use regression modeling: potential for environmental health analyses. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):106–14.

Ross Z, Jerrett M, Ito K, Tempalski B, Thurston GD. A land use regression for predicting fine particulate matter concentrations in the New York City region. Atmos Environ. 2007;41(11):2255–69.

Zhang JJY, Sun L, Barrett O, Bertazzon S, Underwood FE, Johnson M. Development of land-use regression models for metals associated with airborne particulate matter in a North American city. Atmos Environ. 2015;106:165–77.

Dons E, Van Poppel M, Kochan B, Wets G, Int Panis L. Modeling temporal and spatial variability of traffic-related air pollution: hourly land use regression models for black carbon. Atmos Environ. 2013;74:237–46.

Larson T, Henderson SB, Brauer M. Mobile monitoring of particle light absorption coefficient in an urban area as a basis for land use regression. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(13):4672–8.

Smargiassi A, Brand A, Fournier M, Tessier F, Goudreau S, Rousseau J, et al. A spatiotemporal land-use regression model of winter fine particulate levels in residential neighbourhoods. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22(4):331–8.

Saraswat A, Apte JS, Kandlikar M, Brauer M, Henderson SB, Marshall JD. Spatiotemporal land use regression models of fine, ultrafine, and black carbon particulate matter in New Delhi, India. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(22):12903–11.

Wang RR, Henderson SB, Sbihi H, Allen RW, Brauer M. Temporal stability of land use regression models for traffic-related air pollution. Atmos Environ. 2013;64:312–9.

Eeftens M, Beelen R, Fischer P, Brunekreef B, Meliefste K, Hoek G. Stability of measured and modelled spatial contrasts in NO(2) over time. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(10):765–70.

Lee HJ, Koutrakis P. Daily ambient NO2 concentration predictions using satellite ozone monitoring instrument no2 data and land use regression. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(4):2305–11.

Kloog I, Nordio F, Coull BA, Schwartz J. Incorporating local land use regression and satellite aerosol optical depth in a hybrid model of spatiotemporal PM2. 5 exposures in the Mid-Atlantic states. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(21):11913–21.

Beckerman BS, Jerrett M, Serre M, Martin RV, Lee S-J, van Donkelaar A, et al. A hybrid approach to estimating national scale spatiotemporal variability of PM2.5 in the contiguous United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(13):7233–41.

Adam-Poupart A, Brand A, Fournier M, Jerrett M, Smargiassi A. Spatiotemporal modeling of ozone levels in Quebec (Canada): a comparison of kriging, land-use regression (LUR), and combined Bayesian maximum entropy-LUR approaches. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(9):970–6.

Su JG, Jerrett M, Meng Y-Y, Pickett M, Ritz B. Integrating smart-phone based momentary location tracking with fixed site air quality monitoring for personal exposure assessment. Sci Total Environ. 2015;506:518–26.

Patton AP, Zamore W, Naumova EN, Levy JI, Brugge D, Durant JL. Transferability and generalizability of regression models of ultrafine particles in urban neighborhoods in the Boston Area. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(10):6051–60.

Kim KH, Woo D, Lee SB, Bae GN. On-road measurements of ultrafine particles and associated air pollutants in a densely populated area of Seoul Korea. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2015;15(1):142–53.

Hankey S, Marshall JD. Land use regression models of on-road particulate air pollution (particle number, black carbon, PM2.5, particle size) using mobile monitoring. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(15):9194–202.

Waddington CH. Epigenetics and evolution. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1953;7:186–99.

Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev. 2009;23(7):781–3.

Boland MJ, Nazor KL, Loring JF. Epigenetic regulation of pluripotency and differentiation. Circ Res. 2014;115(2):311–24.

Cullen SM, Mayle A, Rossi L, Goodell MA. Hematopoietic stem cell development: an epigenetic journey. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2014;107:39–75.

Timp W, Feinberg AP. Cancer as a dysregulated epigenome allowing cellular growth advantage at the expense of the host. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(7):497–510.

Zemach A, McDaniel IE, Silva P, Zilberman D. Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of eukaryotic DNA methylation. Science. 2010;328(5980):916–9.

Feng S, Cokus SJ, Zhang X, Chen PY, Bostick M, Goll MG, et al. Conservation and divergence of methylation patterning in plants and animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(19):8689–94.

Bostick M, Kim JK, Esteve PO, Clark A, Pradhan S, Jacobsen SE. UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science. 2007;317(5845):1760–4.

Sharif J, Muto M, Takebayashi S, Suetake I, Iwamatsu A, Endo TA, et al. The SRA protein Np95 mediates epigenetic inheritance by recruiting Dnmt1 to methylated DNA. Nature. 2007;450(7171):908–12.

Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462(7271):315–22.

Guo JU, Su Y, Shin JH, Shin J, Li H, Xie B, et al. Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(2):215–22.

Arand J, Spieler D, Karius T, Branco MR, Meilinger D, Meissner A, et al. In vivo control of CpG and non-CpG DNA methylation by DNA methyltransferases. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(6):e1002750.

Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324(5929):930–5.

He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333(6047):1303–7.

Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333(6047):1300–3.

Pastor WA, Aravind L, Rao A. TETonic shift: biological roles of TET proteins in DNA demethylation and transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(6):341–56.

Wu H, Zhang Y. Reversing DNA methylation: mechanisms, genomics, and biological functions. Cell. 2014;156(1–2):45–68.

Ji H, Ehrlich LI, Seita J, Murakami P, Doi A, Lindau P, et al. Comprehensive methylome map of lineage commitment from haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2010;467(7313):338–42.

Zhang X, Ulm A, Somineni HK, Oh S, Weirauch MT, Zhang HX, et al. DNA methylation dynamics during differentiation and maturation of human dendritic cells. Epigenet Chromatin. 2014;7:21.

Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*). Ann Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–89.

Verma M, Chattopadhyay BD, Paul BN. Epigenetic regulation of DNMT1 gene in mouse model of asthma disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(3):2357–68.

Cheng RY, Shang Y, Limjunyawong N, Dao T, Das S, Rabold R, et al. Alterations of the lung methylome in allergic airway hyper-responsiveness. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2014;55(3):244–55.

Somineni HK, Zhang X, Biagini Myers JM, Butsch Kovacic M, Ulm A, Jurcak N, et al. TET1 methylation is associated with childhood asthma and traffic-related air pollution. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(3):797–805.

Zhang Q, Zhao K, Shen Q, Han Y, Gu Y, Li X, et al. Tet2 is required to resolve inflammation by recruiting Hdac2 to specifically repress IL-6. Nature. 2015;525(7569):389–93.

Yu Q, Zhou B, Zhang Y, Nguyen ET, Du J, Glosson NL, et al. DNA methyltransferase 3a limits the expression of interleukin-13 in T helper 2 cells and allergic airway inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(2):541–6.

Ichiyama K, Chen T, Wang X, Yan X, Kim BS, Tanaka S, et al. The methylcytosine dioxygenase Tet2 promotes DNA demethylation and activation of cytokine gene expression in T cells. Immunity. 2015;42(4):613–26.

Begin P, Nadeau KC. Epigenetic regulation of asthma and allergic disease. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2014;10(1):27.

Zeng WP. ‘All things considered’: transcriptional regulation of T helper type 2 cell differentiation from precursor to effector activation. Immunology. 2013;140(1):31–8.

Hwang ES. Transcriptional regulation of T helper 17 cell differentiation. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(4):484–91.

Kumar RK, Hitchins MP, Foster PS. Epigenetic changes in childhood asthma. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(11–12):549–53.

van Panhuys N, Le Gros G, McConnell MJ. Epigenetic regulation of Th2 cytokine expression in atopic diseases. Tissue Antigens. 2008;72(2):91–7.

Lee DU, Agarwal S, Rao A. Th2 lineage commitment and efficient IL-4 production involves extended demethylation of the IL-4 gene. Immunity. 2002;16(5):649–60.

White GP, Watt PM, Holt BJ, Holt PG. Differential patterns of methylation of the IFN-gamma promoter at CpG and non-CpG sites underlie differences in IFN-gamma gene expression between human neonatal and adult CD45RO- T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(6):2820–7.

Jones B, Chen J. Inhibition of IFN-gamma transcription by site-specific methylation during T helper cell development. EMBO J. 2006;25(11):2443–52.

Brand S, Kesper DA, Teich R, Kilic-Niebergall E, Pinkenburg O, Bothur E, et al. DNA methylation of TH1/TH2 cytokine genes affects sensitization and progress of experimental asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1602–10.

Stelmaszczyk-Emmel A. Regulatory T cells in children with allergy and asthma: it is time to act. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;209:59–63.

Runyon RS, Cachola LM, Rajeshuni N, Hunter T, Garcia M, Ahn R, et al. Asthma discordance in twins is linked to epigenetic modifications of T cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48796.

Agache I, Ciobanu C, Agache C, Anghel M. Increased serum IL-17 is an independent risk factor for severe asthma. Respir Med. 2010;104(8):1131–7.

Chien JW, Lin CY, Yang KD, Lin CH, Kao JK, Tsai YG. Increased IL-17A secreting CD4+ T cells, serum IL-17 levels and exhaled nitric oxide are correlated with childhood asthma severity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(9):1018–26.

Alyasin S, Karimi MH, Amin R, Babaei M, Darougar S. Interleukin-17 gene expression and serum levels in children with severe asthma. Iran J Immunol. 2013;10(3):177–85.

Irvin C, Zafar I, Good J, Rollins D, Christianson C, Gorska MM, et al. Increased frequency of dual-positive TH2/TH17 cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid characterizes a population of patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1175–86.

Yang BH, Floess S, Hagemann S, Deyneko IV, Groebe L, Pezoldt J, et al. Development of a unique epigenetic signature during in vivo Th17 differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(3):1537–48.

Thomas RM, Sai H, Wells AD. Conserved intergenic elements and DNA methylation cooperate to regulate transcription at the il17 locus. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(30):25049–59.

Nicodemus-Johnson J, Naughton KA, Sudi J, Hogarth K, Naurekas ET, Nicolae DL, et al. Genome-wide methylation study identifies an IL-13 induced epigenetic signature in asthmatic airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(4):376–85.

Yang IV, Pedersen BS, Liu A, O’Connor GT, Teach SJ, Kattan M, et al. DNA methylation and childhood asthma in the inner city. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):69–80.

Liang L, Willis-Owen SA, Laprise C, Wong KC, Davies GA, Hudson TJ, et al. An epigenome-wide association study of total serum immunoglobulin E concentration. Nature. 2015;520(7549):670–4.

Murphy TM, Wong CC, Arseneault L, Burrage J, Macdonald R, Hannon E, et al. Methylomic markers of persistent childhood asthma: a longitudinal study of asthma-discordant monozygotic twins. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:130.

Zhang H, Tong X, Holloway JW, Rezwan FI, Lockett GA, Patil V, et al. The interplay of DNA methylation over time with Th2 pathway genetic variants on asthma risk and temporal asthma transition. Clin Epigenetics. 2014;6(1):8.

Mill J, Heijmans BT. From promises to practical strategies in epigenetic epidemiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(8):585–94.

Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(7):484–92.

van Eijk KR, de Jong S, Boks MP, Langeveld T, Colas F, Veldink JH, et al. Genetic analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression levels in whole blood of healthy human subjects. BMC Genom. 2012;13:636.

Wagner JR, Busche S, Ge B, Kwan T, Pastinen T, Blanchette M. The relationship between DNA methylation, genetic and expression inter-individual variation in untransformed human fibroblasts. Genome Biol. 2014;15(2):R37.

Morales E, Bustamante M, Vilahur N, Escaramis G, Montfort M, de Cid R, et al. DNA hypomethylation at ALOX12 is associated with persistent wheezing in childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(9):937–43.

Acevedo N, Reinius LE, Greco D, Gref A, Orsmark-Pietras C, Persson H, et al. Risk of childhood asthma is associated with CpG-site polymorphisms, regional DNA methylation and mRNA levels at the GSDMB/ORMDL3 locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(3):875–90.

Ji H, Khurana Hershey GK. Genetic and epigenetic influence on the response to environmental particulate matter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(1):33–41.

Liu J, Ballaney M, Al-alem U, Quan C, Jin X, Perera F, et al. Combined inhaled diesel exhaust particles and allergen exposure alter methylation of T helper genes and IgE production in vivo. Toxicol Sci. 2008;102(1):76–81.

Xia M, Viera-Hutchins L, Garcia-Lloret M, Noval Rivas M, Wise P, McGhee SA, et al. Vehicular exhaust particles promote allergic airway inflammation through an aryl hydrocarbon receptor-notch signaling cascade. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(2):441–53.

Breton CV, Marutani AN. Air pollution and epigenetics: recent findings. Curr Envir Health Rpt. 2014;1:35–45.

Miousse IR, Chalbot MC, Pathak R, Lu X, Nzabarushimana E, Krager K, et al. In vitro toxicity and epigenotoxicity of different types of ambient particulate matter. Toxicol Sci. 2015;148(2):473–87.

Tarantini L, Bonzini M, Apostoli P, Pegoraro V, Bollati V, Marinelli B, et al. Effects of particulate matter on genomic DNA methylation content and iNOS promoter methylation. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(2):217–22.

Breton CV, Byun HM, Wang X, Salam MT, Siegmund K, Gilliland FD. DNA methylation in the arginase-nitric oxide synthase pathway is associated with exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(2):191–7.

Breton CV, Salam MT, Wang X, Byun HM, Siegmund KD, Gilliland FD. Particulate matter, DNA methylation in nitric oxide synthase, and childhood respiratory disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(9):1320–6.

Madrigano J, Baccarelli A, Mittleman MA, Sparrow D, Spiro A 3rd, Vokonas PS, et al. Air pollution and DNA methylation: interaction by psychological factors in the VA normative aging study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(3):224–32.

Kile ML, Fang S, Baccarelli AA, Tarantini L, Cavallari J, Christiani DC. A panel study of occupational exposure to fine particulate matter and changes in DNA methylation over a single workday and years worked in boilermaker welders. Environ Health. 2013;12(1):47.

Salam MT, Byun HM, Lurmann F, Breton CV, Wang X, Eckel SP, et al. Genetic and epigenetic variations in inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter, particulate pollution, and exhaled nitric oxide levels in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(1):232–9.

Fitzpatrick AM, Brown LA, Holguin F, Teague WG, National Institutes of Health/National Heart L, Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research P. Levels of nitric oxide oxidation products are increased in the epithelial lining fluid of children with persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(5):990–6.

Bastain TM, Islam T, Berhane KT, McConnell RS, Rappaport EB, Salam MT, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide, susceptibility and new-onset asthma in the children’s health study. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(3):523–31.

Sofer T, Baccarelli A, Cantone L, Coull B, Maity A, Lin X, et al. Exposure to airborne particulate matter is associated with methylation pattern in the asthma pathway. Epigenomics. 2013;5(2):147–54.

Nadeau K, McDonald-Hyman C, Noth EM, Pratt B, Hammond SK, Balmes J, et al. Ambient air pollution impairs regulatory T-cell function in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(4):845–52.

Kohli A, Garcia MA, Miller RL, Maher C, Humblet O, Hammond SK, et al. Secondhand smoke in combination with ambient air pollution exposure is associated with increasedx CpG methylation and decreased expression of IFN-gamma in T effector cells and Foxp3 in T regulatory cells in children. Clin Epigenet. 2012;4(1):17.

Bind MA, Lepeule J, Zanobetti A, Gasparrini A, Baccarelli A, Coull BA, et al. Air pollution and gene-specific methylation in the normative aging study: association, effect modification, and mediation analysis. Epigenetics. 2014;9(3):448–58.

Brunst KJ, Leung YK, Ryan PH, KhuranaHershey GK, Levin L, Jiii H, et al. Forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) hypermethylation is associated with diesel exhaust exposure and risk for childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2):592–4.

Sanchez-Guerra M, Zheng Y, Osorio-Yanez C, Zhong J, Chervona Y, Wang S, et al. Effects of particulate matter exposure on blood 5-hydroxymethylation: results from the Beijing truck driver air pollution study. Epigenetics. 2015;10(7):633–42.

Guo L, Byun HM, Zhong J, Motta V, Barupal J, Zheng Y, et al. Effects of short-term exposure to inhalable particulate matter on DNA methylation of tandem repeats. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2014;55(4):322–35.

Bellavia A, Urch B, Speck M, Brook RD, Scott JA, Albetti B, et al. DNA hypomethylation, ambient particulate matter, and increased blood pressure: findings from controlled human exposure experiments. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(3):e000212.

Jiang R, Jones MJ, Sava F, Kobor MS, Carlsten C. Short-term diesel exhaust inhalation in a controlled human crossover study is associated with changes in DNA methylation of circulating mononuclear cells in asthmatics. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:71.

Clifford RL, Jones MJ, MacIssac JL, McEwen LM, Goodman SJ, Mostafavi S, et al. Inhalation of diesel exhaust and allergen alters human bronchial epithelium DNA methylation. J Allergy Clinl Immunol. 2016;S0091–6749(16):30273–4.

Perera F, Tang WY, Herbstman J, Tang D, Levin L, Miller R, et al. Relation of DNA methylation of 5′-CpG island of ACSL3 to transplacental exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and childhood asthma. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(2):e4488.

Tang WY, Levin L, Talaska G, Cheung YY, Herbstman J, Tang D, et al. Maternal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and 5′-CpG methylation of interferon-gamma in cord white blood cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(8):1195–200.

Hollingsworth JW, Maruoka S, Boon K, Garantziotis S, Li Z, Tomfohr J, et al. In utero supplementation with methyl donors enhances allergic airway disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(10):3462–9.

Whitrow MJ, Moore VM, Rumbold AR, Davies MJ. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(12):1486–93.

Fu A, Leaderer BP, Gent JF, Leaderer D, Zhu Y. An environmental epigenetic study of ADRB2 5′-UTR methylation and childhood asthma severity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(11):1575–81.

Hew KM, Walker AI, Kohli A, Garcia M, Syed A, McDonald-Hyman C, et al. Childhood exposure to ambient polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is linked to epigenetic modifications and impaired systemic immunity in T cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):238–48.

Zhao Z, Chen L, Dawlaty MM, Pan F, Weeks O, Zhou Y, et al. Combined loss of Tet1 and Tet2 promotes B cell, but not myeloid malignancies, mice. Cell Rep. 2015;13(8):1692–704.

Cimmino L, Dawlaty MM, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Yap YS, Bakogianni S, Yu Y, et al. TET1 is a tumor suppressor of hematopoietic malignancy. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(6):653–62.

Yang R, Qu C, Zhou Y, Konkel JE, Shi S, Liu Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes Tet1- and Tet2-mediated Foxp3 demethylation to drive regulatory T cell differentiation and maintain immune homeostasis. Immunity. 2015;43(2):251–63.

Toker A, Engelbert D, Garg G, Polansky JK, Floess S, Miyao T, et al. Active demethylation of the Foxp3 locus leads to the generation of stable regulatory T cells within the thymus. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3180–8.

Yue X, Trifari S, Aijo T, Tsagaratou A, Pastor WA, Zepeda-Martinez JA, et al. Control of Foxp3 stability through modulation of TET activity. J Exp Med. 2016;213(3):377–97.

Watson CJ, Collier P, Tea I, Neary R, Watson JA, Robinson C, et al. Hypoxia-induced epigenetic modifications are associated with cardiac tissue fibrosis and the development of a myofibroblast-like phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(8):2176–88.

Mariani CJ, Vasanthakumar A, Madzo J, Yesilkanal A, Bhagat T, Yu Y, et al. TET1-mediated hydroxymethylation facilitates hypoxic gene induction in neuroblastoma. Cell Rep. 2014;7(5):1343–52.

Pialoux V, Mounier R, Brown AD, Steinback CD, Rawling JM, Poulin MJ. Relationship between oxidative stress and HIF-1 alpha mRNA during sustained hypoxia in humans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(2):321–6.

Vorrink SU, Domann FE. Regulatory crosstalk and interference between the xenobiotic and hypoxia sensing pathways at the AhR-ARNT-HIF1alpha signaling node. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;218:82–8.

Perzanowski MS, Chew GL, Divjan A, Jung KH, Ridder R, Tang D, et al. Early-life cockroach allergen and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposures predict cockroach sensitization among inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(3):886–93.

Patel MM, Quinn JW, Jung KH, Hoepner L, Diaz D, Perzanowski M, et al. Traffic density and stationary sources of air pollution associated with wheeze, asthma, and immunoglobulin E from birth to age 5 years among New York City children. Environ Res. 2011;111(8):1222–9.

Rosa MJ, Jung KH, Perzanowski MS, Kelvin EA, Darling KW, Camann DE, et al. Prenatal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, environmental tobacco smoke and asthma. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):869–76.

Jedrychowski WA, Perera FP, Maugeri U, Mrozek-Budzyn D, Mroz E, Klimaszewska-Rembiasz M, et al. Intrauterine exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, fine particulate matter and early wheeze. Prospective birth cohort study in 4-year olds. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(4):723–32.

Manners S, Alam R, Schwartz DA, Gorska MM. A mouse model links asthma susceptibility to prenatal exposure to diesel exhaust. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(1):63–72.

Yauk C, Polyzos A, Rowan-Carroll A, Somers CM, Godschalk RW, Van Schooten FJ, et al. Germ-line mutations, DNA damage, and global hypermethylation in mice exposed to particulate air pollution in an urban/industrial location. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(2):605–10.

Authors’ contributions

HJ discussed the epigenetic findings related to asthma and TRAP; EBB summarized the molecular and cellular mechanisms undering responses to TRAP and asthma development; JMBM complied the epidemiological evidence supporting the role of TRAP in asthma development; CB and PHR discussed the assessment of TRAP exposure; all authors contributed to the preparation of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cynthia Chappell for administrative assistance with this review.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial support

This work was supported by the following Grants: 2U19AI70235 (GKKH, JBM), R01ES019890 (PHR), and NIH/NIAID R21AI119236 (HJ) and NIH/NIEHS P30ES006096 (HJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, H., Biagini Myers, J.M., Brandt, E.B. et al. Air pollution, epigenetics, and asthma. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 12, 51 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-016-0159-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-016-0159-4