Abstract

Purpose

Thousands of aquifers worldwide have been polluted by leachate from landfills and many more remained threatened. Microbial communities from these environments play a crucial role in mediating biodegradation and maintaining the biogeochemical cycles, but their co-occurrence and assembly mechanism have not been investigated.

Method

Here, we coupled network analysis with multivariate statistics to assess the relative importance of deterministic versus stochastic microbial assembly in an aquifer undergoing intrinsic remediation, using 16S metabarcoding data generated through Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the archaeal/bacterial V3–V4 hypervariable region.

Results

Results show that both the aquifer-wide and localised community co-occurrences deviate from expectations under null models, indicating the predominance of deterministic processes in shaping the microbial communities. Further, the amount of variation in the microbial community explained by the measured environmental variables was 55.3%, which illustrates the importance of causal factors in forming the structure of microbial communities in the aquifer. Based on the network topology, several putative keystone taxa were identified which varied remarkably among the wells in terms of their number and composition. They included Nitrospira, Nitrosomonadaceae, Patulibacter, Legionella, uncharacterised Chloroflexi, Vicinamibacteriales, Neisseriaceae, Gemmatimonadaceae, and Steroidobacteraceae. The putative keystone taxa may be providing crucial functions in the aquifer ranging from nitrogen cycling by Nitrospira, Nitrosomonadaceae, and Steroidobacteraceae, to phosphorous bioaccumulation by Gemmatimonadaceae.

Conclusion

Collectively, the findings provide answers to fundamental ecological questions which improve our understanding of the microbial ecology of landfill leachate plumes, an ecosystem that remains understudied.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Groundwater ecosystems harbour the largest terrestrial biome, accounting for up to 40% of the earth’s freshwater prokaryotic biomass (Griebler and Lueders 2009; Griebler et al. 2014). This rich biodiversity is threatened on a global scale because of groundwater contamination. There are thousands of cases of groundwater contamination globally due to landfill operations. A good amount of research has focused on characterising landfill leachate chemistry (Kjeldsen et al. 2002; Masoner et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2018) and groundwater leachate plumes (Abiriga et al. 2020, 2021d; Bjerg et al. 2011; Christensen et al. 2001). While research on leachate microbiology is now gaining momentum (Rajasekar et al. 2018; Song et al. 2015b; Staley et al. 2018; Zainun and Simarani 2018), our understanding of the microbial ecology of landfill-leachate-impacted aquifers remains scant. The chemical composition of landfill leachate is complex (Christensen et al. 2000; Eggen et al. 2010; Moody and Townsend 2017; Mouser et al. 2005) and may contain chemicals that are toxic to microorganisms in the leachate-receiving groundwater. As landfill leachate production may last for decades to centuries (Bjerg et al. 2011), the long-term release of toxic compounds can even result in permanently eliminating the native species due to chronic disturbances (Herzyk et al. 2017; Song et al. 2015a). Thus, landfill contaminations are press perturbations. Press perturbations are disturbances due to persistent discharge of contaminants into an environmental medium such as groundwater, soil, lake, and river (Zhou et al. 2014).

The complex mix of contaminants in landfill leachate limits the applicability of conventional treatments for landfill leachates and necessitates more robust approaches. Natural attenuation is considered superior in this respect (Mouser et al. 2005). The better treatment outcome from natural attenuation signifies the roles of the intrinsic microorganisms, because biodegradation, which is a core process in natural attenuation, is mediated by microbes. Studying the microbiology of landfill leachate plumes not only informs on the effect of the leachate on the microbial communities, but also informs on the potential of the resident microbial communities to degrade contaminants in the plumes.

Previous microbiological studies from landfill leachate plumes (Abiriga et al. 2021a; Lu et al. 2012; Mouser et al. 2005; Taş et al. 2018) have almost exclusively focused on one aspect of microbial ecology such as alpha diversity, beta diversity, or microbial functions. We previously showed how multiple factors can affect microbial community composition in an aquifer (Abiriga et al. 2021b). While these studies have given significant insights into the microbiology of landfill leachate plumes, the aspect of microbial co-occurrence and the relative importance of deterministic versus stochastic microbial community assembly remains unexplored. Knowing whether microbial communities assemble deterministically or stochastically is very crucial in understanding how the communities evolve and sustain. This presents an important knowledge gap in our understanding of the microbial ecology of landfill-perturbed aquifers.

Network analysis has been successfully applied to study microbial co-occurrence across multitudes of habitats (Barberán et al. 2012; de Vries et al. 2018; Horner-Devine et al. 2007; Ju et al. 2014; Lupatini et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2014) and has helped resolved aspects of microbial ecology that cannot be addressed by community metrics such as alpha and beta diversities (Lupatini et al. 2014). Analysis of co-occurrence patterns can decipher otherwise inaccessible aspects of complex microbial systems such as providing information on the ecological traits of uncharacterised microbes that co-occur with well characterised microbes (Barberán et al. 2012; Fuhrman 2009; Williams et al. 2014). This may allow such taxa, which are very difficult to cultivate in the laboratory, to be grown in a co-culture with the well characterised species (Lupatini et al. 2014). The contribution of deterministic processes in shaping the aquifer microbiology was quantified by applying a multivariate statistic by leveraging on the environmental data. Coupling network analysis to multivariate statistics offers a better interpretation of microbial community data (Williams et al. 2014).

The main objectives of the study were to answer the following questions: (i) which taxa show strong and significant interactions? (ii) Which are the keystone taxa and how do they compare among sampling wells? (iii) Do the microbial taxa in the aquifer assemble deterministically or stochastically? Answering these fundamental ecological questions should give insight into the microbial ecology of understudied landfill-perturbed environments.

Materials and methods

The study aquifer and field procedures

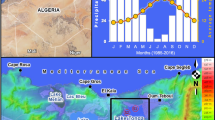

The study aquifer is a confined aquifer of Quaternary glaciofluvial deposit located in southeast Norway (Fig. 1). The aquifer matrix is characterised by medium to high permeability sand and gravel (Abiriga et al. 2020; Klempe 2004, 2015). It is a small aquifer fed by a small watershed (Klempe 2015). In the period 1974–1996, a municipal landfill was operated in the area and because no leachate containment system was in place, the leachate from the landfill contaminated the aquifer. Additional information on the study site is accessible elsewhere (Abiriga et al. 2020, 2021c, d; Klempe 2004, 2015).

Groundwater samples were collected twice a year, in spring and autumn, in 2018 and 2019 from four monitoring wells: R1 (the proximal well), R2 (the intermediate well) and R4 (the distal well) located in the contaminated aquifer, and R0 (the background well) located in a nearby uncontaminated aquifer (Fig. 1). The proximal, intermediate, and distal wells are located downstream of the landfill at 26 m, 88 m, and 324 m, respectively. The proximal and intermediate wells are multilevel sampling wells constructed using the Waterloo Groundwater Monitoring System, equipped with five and four levels, respectively. The distal well consist of a cluster of three 25 mm diameter PVC pipes installed at different depths. In this study, however, only one level was considered in each of the wells: R104 (proximal), R203 (intermediate), and R402 (distal); all from the middle level of the aquifer.

In total, 48 groundwater samples were analysed, with three samples taken in spring and another three in autumn which makes 12 from each of the four wells over the 2-year period. Groundwater samples from the proximal and intermediate wells were obtained by a repeated cycle of applying nitrogen pressure through drive valves and venting, until groundwater samples emerge through the Teflon tubes with a gentle pulsating flow. Samples from the distal well were taken using a hand pump, while those from the background well were taken using a submersible pump. In all the cases, samples were collected after purging the well volume (distal and background wells) and micro-purging (proximal and intermediate wells) in accordance with ISO 5667-11 (2009). Samples for microbiology were collected in sterile 350 ml PETE bottles (VWR, UK) without headspace, while those for groundwater geochemistry were collected in 500 ml PETE bottles. pH and electrical conductivity were determined onsite, while dissolved oxygen was fixed onsite and later determined in the laboratory using the Winkler method (Winkler 1888). The samples were maintained at ≤ 4 °C in cooler boxes and transported to the laboratory at University of South-Eastern Norway.

Laboratory procedures

Groundwater chemical analyses have been described previously (Abiriga et al. 2021a). The samples were analysed for 15 physicochemical parameters: pH, dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity, sodium, potassium, ammonium, calcium, magnesium, iron, manganese, chloride, nitrate, alkalinity, sulphate, and total nitrogen using standard analytical methods (Abiriga et al. 2021a).

A total of 300 ml of each of the samples for microbiology in sterile PETE bottles was filtered through 0.2 μm polycarbonate membrane filter upon arrival at the laboratory. The filters were stored at − 70 °C prior to DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from one half filters using DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quantity was measured using Qubit Fluorometer 3.0 (Life Technologies, Malaysia), while the quality was assessed using Nanodrop spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, China) and 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA samples were sent to Norwegian Sequencing Centre (https://www.sequencing.uio.no), where PCR amplification, library preparation and sequencing were conducted. The V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primer set 319F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) (Lane 1991) and the modified 805R (5′-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) (Apprill et al. 2015). Library preparation was conducted following the Fadrosh et al. protocol (Fadrosh et al. 2014), with the forward and reverse oligos consisting of an Illumina-specific adaptor sequence, a 12-nucleotide barcode sequence, a heterogeneity spacer, and the primer set. The 16S rRNA gene fragment library was sequenced using Illumina MiSeq, by applying the 300 bp paired-end protocol v3 (600-cycle kit) with 10% PhiX as the control library.

Sequence analysis

The DNA sequences were demultiplexed using a demultiplexer accessible at https://github.com/nsc-norway/triple_index-demultiplexing/tree/master/src. During this step, barcode sequences and the heterogeneity spacers were removed. The DNA sequences were quality-filtered (primer trimming, and removal of short sequences and chimeras), dereplicated, merged, and assigned to amplicon sequencing variants using DADA2 (Callahan et al. 2016) plug-in for QIIME2 v.2019.1.0 (Bolyen et al. 2019). All the steps were run using the default parameters except the primer length (set to 20 bp) and minimum length of reads (set to 280 bp). The amplicon sequencing variants (ASVs) were subjected to taxonomic assignment using Naïve Bayes classifier algorithm trained on data from SILVA v.138 conducted in QIIME2 v.2020.2.0 (Bolyen et al. 2019). The library statistics are provided in the supplementary information (Table S3).

Statistical data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R v.4.0.2 (R Core Team 2020). The microbial community dataset used in all the analyses was classified at genus level of taxonomy. The alpha diversity (Shannon index) was calculated using package phyloseq v.1.38.0 (McMurdie and Holmes 2013). Difference in Shannon diversity index across the sampling wells was tested for significance using one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s HSD for pairwise comparisons. Differences in Shannon diversity index between 2018 and 2019 and between autumn and spring were tested for significance using Student’s t test. Multivariate analyses: nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) (Anderson 2001), variation partitioning (Borcard et al. 1992), and rarefaction (Fig. S1) were performed using package vegan v.2.5.6 (Oksanen et al. 2019). As water chemistry datasets are dimensionally heterogeneous (measured in different units), the data was standardised prior to variation partitioning, as was the microbial community dataset, which was square-root transformed and Hellinger standardised (Legendre and Gallagher 2001) prior to multivariate analysis. NMDS was used to visualise beta diversity based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity measure. The sample clusters in the NMDS were tested for significant difference using PERMANOVA on 9999 permutations. Group homogeneity was assessed using function ‘betadisper’ (Anderson 2006). Likewise, the change in the beta diversity between the 2 years (2018 and 2019) and seasons (spring and autumn) were analysed for significance using PERMANOVA on 9999 permutations. The contribution of the measured variables in explaining the variation in the microbial community composition was analysed using variation partitioning (Borcard et al. 1992). Total nitrogen and ammonium were removed from the dataset during variation partitioning, due to missing observations. The species community dataset was used without filtering (background, proximal, intermediate, distal wells; N = 48, 1979 taxa) as it is important to perform the above analysis on the full community dataset. Statistical tests were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Prior to the network analysis, the community data from each of the wells was filtered by selecting taxa present more than 5 times in at least 50% of the samples from each of the well. Subsequently, the 25 most abundant taxa in the respective samples were chosen for further analysis. This reduced the number of taxa remarkably to only include the core members of the communities (from 616 to 82 taxa in R0; 1103 to 94 in R104; 1223 to 117 in R203; and 1186 to 81 in R402). Thus reducing the network complexity and eliminating taxa that were rare and/or showed multiple zero abundances, which should be avoided (Banerjee et al. 2018). From the quality filtered data, taxa co-occurrence based on Spearman’s rank correlations was calculated separately for each of the wells. The co-occurrence network was generated using package igraph v.1.2.6 (Csardi and Nepusz 2006), using an R script from the literature (Ju et al. 2014) on Github (https://github.com/RichieJu520/Co-occurrence_Network_Analysis). Only taxa having significant positive correlations (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected Spearman’s rank correlations, ρ > 0.6; P < 0.01) were displayed in the co-occurrence network. We focused exclusively on the positive associations because we think that in environmental systems such the studied aquifer, which is influenced by the operation of the landfill, microbial communities may need to cooperate and/or prefer common conditions, since positive associations may indicate common preference to conditions or cooperative associations (Fuhrman 2009). In our setting, such cooperative interactions may reflect co-metabolism, a function which is central in biodegradation in contaminated systems such as the present study aquifer, hence the need to focused on positive associations. Network visualization was performed in Gephi v.0.9.2 (Bastian et al. 2009). The network topologies of the final model were compared with those generated from a random network according to the literature (Erdős and Rényi 1960). The key network topological properties evaluated to identify community functions included betweenness centrality (the number of shortest paths going through a vertex (node)) used to delineate keystone taxa (Williams et al. 2014; Guo et al. 2022), node degree (the number of connections to other nodes) (Faust and Raes 2012; Guo et al. 2022), and closeness centrality. In addition, parameter estimations: within-module connectivity (Zi) and between-module connectivity (Pi) for identification of topological roles were calculated using package microeco (Liu et al. 2021). Prior to the network analysis, the taxa co-occurrence was evaluated for randomness by simulating a null community co-occurrence using the checkerboard-score (C-score) in package EcoSimR v.0.1.0 (Gotelli et al. 2015) for each of the wells, which were treated as independent communities. The null community co-occurrence (null model) assumes that co-occurrence patterns arise by chance (Gotelli et al. 2015).

Results

Community diversity metrics and variation partitioning

Alpha diversity was highest in the intermediate well and lowest in the distal well (Fig. 2a). Tukey’s honest significance difference (Table 1) indicates that the Shannon diversity index varied significantly between most of the combination of pairs except between the background and distal wells, and between the proximal and intermediate wells. Further, a t test performed on Shannon diversity index indicated non-significant differences between 2018 and 2019, and between spring and autumn, for nearly all the wells, except a significant seasonal difference in the background well (P = 0.04) and a significant yearly difference in the distal well (P = 0.04) (Table S1).

a Shannon diversity index across the sampling wells, calculated from data collected in the period 2018-2019. Each point represents a sample. The asterisk indicates an outlier. b Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot of sites based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity distance. R0: background well; R104: proximal well; R203: intermediate well; R402: distal well

Beta diversity analysis based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metric shows distinct microbial community composition across the wells, although a slight overlap between the proximal and intermediate wells exists (Fig. 2b). The first axis (NMDS1) separates the wells by aquifer type. The proximal, intermediate, and distal wells from the contaminated aquifer correlated positively with NMDS1, while the background well from the uncontaminated aquifer correlated negatively with NMDS1. The second axis (NMDS2) separates the wells by the degree of groundwater contamination. The uncontaminated groundwater from the background well and the less contaminated groundwater from the distal well both correlated negatively with NMDS2. On the other hand, the more contaminated groundwater from the proximal and intermediate wells correlated positively with NMDS2.

The groups in the NMDS were tested for significant difference using PERMANOVA. Both the global and pairwise analyses showed statistically significant differences across (F3.0 = 11.8, P = 0.001) and between the wells (Table 2). Similarly, differences in microbial community composition between spring and autumn and between 2018 and 2019 were tested. Results indicated non-significant differences in the microbial community composition between spring and autumn (F1.0 = 1.13, P = 0.273) and between 2018 and 2019 (F1.0 = 1.11, P = 0.288).

The variation in the microbial community composition (Fig. 3) partitioned among the variables: water chemistry (47.6%, F = 4.29, P = 0.001), well (44.8%, F = 13.7, P = 0.001), and both season and time (year) (0.4%, P > 0.05). Removing the effects of covariables resulted in explained variances of 7.5%, 4.5%, 1.1%, and 0.7% for water chemistry, well, season, and year, respectively. Of the explained variance (55.3%), 42.5% of this was accounted for by an interaction term between the groundwater chemistry and well, leaving only 12.8% of the variance attributable to the other terms in the model. The collective variance (that explained by all the variables together) was only 0.4%, and the unexplained variance was 44.7%. A summary of the groundwater geochemistry can be accessed from the supplementary information (Table S2).

Co-occurrence network

Implementing the quality filtering and network selection criteria resulted in 33 nodes and 29 edges (background well), 70 nodes and 196 edges (proximal well), 58 nodes and 86 edges (intermediate well), and 8 nodes and 13 edges (distal well) (Figs. 4 and 5). The taxa with the most number of connections were Nitrospira, Acidobacteriae, and Babeliales in the background well with all having 3 connections; Candidate Kaiserbacteria, Omnitrophales, and Chloroflexi in the proximal well with each having 15, 13, and 12 connections respectively; Patulibacter, Legionella and Neisseriaceae in the intermediate well with each having 9, 8, and 7 connections respectively; and Chloroflexi and Nitrosomonadaceae in the distal well with both having 2 connections (Figs. 4 and 5).

Co-occurrence network in the background (a) and proximal (b) wells. Each connection represents a strong positive and significant Spearman’s correlation (ρ > 0.6, P < 0.01) and the thickness of the connections is proportional to the correlation coefficient. The size of the nodes is proportional to the node degree (number of connections), and the node colours represent microbial phyla

Co-occurrence network in the intermediate (a) and distal (b) wells. Each connection represents a strong positive and significant Spearman’s correlation (ρ > 0.6, P < 0.01) and the thickness of the connections is proportional to the correlation coefficient. The size of the nodes is proportional to the node degree (number of connections), and the node colours represent microbial phyla

Based on a combination of the network topological parameters (node degree, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality), 19 taxa were designated as putative keystone taxa in the four communities (Tables S4–S7); although when the Zi-Pi model was applied, neither network hubs nor module hubs were identified except a node connector (Figs. S2–S5). The keystone taxa varied between and among the four communities (wells) in both number and composition. Those in the background comprised three taxa: Nitrospira, Acidobacteriae, and Babeliales. The most diverse and numerous (eight) keystone taxa were from the proximal well and consisted of Vicinamibacterales, Chloroflexi, Candidate Kaiserbacteria, Parcubacteria, Gemmatimonadaceae, Candidate phylum MBNT15, Omnitrophales, and Elusimicrobiota. Six keystone taxa were identified in the intermediate well which included Patulibacter, Legionella, Neisseriaceae, Nitrospira, Nitrosomonadaceae, and Steroidobacteraceae. The least diverse and the lowest number of keystone taxa was recorded in the distal well with Chloroflexi and Nitrosomonadaceae as the only taxa.

A well-by-well basis simulation of null communities showed significant non-random taxa co-occurrence in the proximal, intermediate, and distal wells (Table 3). Among these wells, the standardised effect size (SES) was highest in the intermediate well, moderate in the distal well and lowest in the proximal well. The background well by contrast, showed a non-significant marginally higher C-score (2.9333) than expected under random null model (2.9301), with 70/1000 simulations occurring more than the observed C-score.

Discussion

The network complexity varied notably among the four communities, with the proximal well showing the most complex taxa co-occurrence network while the distal having the least complex structure (Figs. 4 and 5). Similarly, the putative keystone taxa varied remarkably among the communities (Tables S4–S7). These results hint on inherent variations in community composition and interactions in situ. Taxa such as Gemmatimonadaceae, Nitrospira, and Nitrosomonadaceae were identified as putative keystone taxa (Tables S4–S7). Bioaccumulation of polyphosphate is a feature of two of the three species (as of writing this manuscript) of phylum Gemmatimonadetes (Pascual et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2003). Making phosphorous bioavailable can be viewed as provision of ‘public goods’ of the microbial community that increase its stability and diversity (Konopka et al. 2015). Nitrospira and Nitrosomonadaceae may be involved in nitrogen cycling, as both nitrate and ammonium were present in the groundwater samples (Table S2). Moreover, the identification of Nitrosomonadaceae in the background, intermediate, and distal wells suggest the taxon is a potential cosmopolitan taxon in the area. Whereas the Nitrospira was designated as a node connector in the intermediate well (Fig. S4), implying that it plays an important role in inter-module communication within the community (Guo et al. 2022).

Taxon Parcubacteria (Candidate Jorgensenbacteria and Candidate Kaiserbacteria) belonging to phylum Patescibacteria form an important part of the network particularly in the proximal well. Patescibacteria are episymbionts (Castelle et al. 2018) and the strong correlations with other taxa in the co-occurrence network may therefore suggest potential host-symbiont relationship. Network analyses provide starting point for empirical observation and hypothesis testing, as well as for identifying ecological traits (Banerjee et al. 2018; Fuhrman 2009; Williams et al. 2014). Thus, the connection of Patescibacteria to many cultivable microbes suggests a way forward in the in vitro co-cultivation of Patescibacteria. Currently, no cultured representatives of the taxon exist (Brown et al. 2015; Kantor et al. 2013; Wrighton et al. 2012) and little is known about them (Castelle et al. 2018), yet they are abundant in groundwater (Herrmann et al. 2019).

Well-by-well null models showed non-random community co-occurrences in the contaminated aquifer. Non-random co-occurrence implies deterministic factors operate to shape the microbial communities (Horner-Devine et al. 2007). In the present study, the main driving factor is the landfill leachate and because this varies from well to well due to natural attenuation (Abiriga et al. 2020), a gradient exists and the communities from the wells showed idiosyncratic co-occurrence patterns. Thus, the proximal and distal wells represent opposing ends of a spectrum, with the proximal being highly influenced while the distal being least impacted. From an ecological point of view, this presents differences in niche-based processes that may be characterised by successions analogous to those observed in perturbation experiments (Herzyk et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2014) as conditions revert to normal. The low SES (Table 3) recorded in the proximal well indicates that the microbial taxa in the proximal well co-occur more than in the intermediate and distal wells. This attests to our assertion that environmental filtering due to the leachate is strongest in the proximal well due to its proximity to the landfill (Abiriga et al. 2021a). The strong disturbance in the proximal well like other perturbations, will increase cell mortality and niche selection, and decrease microbial diversity and ecological drift (Zhou et al. 2014), causing the taxa to coexist more than in the intermediate and distal wells.

In the intermediate well, disturbance is expected to be of an intermediate strength. The higher SES and alpha diversity in the intermediate well agree with the ‘intermediate disturbance’ hypothesis that the highest diversity occurs at an intermediate level of disturbance (Miller et al. 2011; Svensson et al. 2012). Probable mechanisms shaping the microbial community in the intermediate well are niche-based processes such as predation and symbiosis. Some of the endosymbionts showed higher abundance in the intermediate well (Fig. S6).

In the distal well where the influence of leachate is expected to be minimal due to leachate attenuation (Abiriga et al. 2020) gives room to other ecological processes to drive the microbial community. This may include variable selection, competition, predation, and phylogenetic history. The same endosymbionts present in the intermediate well were also present here.

In contrast to the contaminated aquifer, the null model analysis of the background well showed only a marginally larger but non-significant observed C-score. This suggests that the microbial community in the background well exhibits some degree of aggregation. Evidence of putative aggregation is the co-occurrence of 7% of the 1000 simulations more than the observed. Possible explanations for species aggregation are mutualistic and syntrophic interactions (Horner-Devine et al. 2007).

Identifying the ecological processes shaping community compositions in any system involves identifying whether it is deterministic or stochastic. While our analysis does not identify the causal mechanistic processes, the non-random community assembly patterns do indicate the dominance of deterministic processes (Horner-Devine et al. 2007). Variation partitioning was employed to quantify the overall contribution of deterministic factors in shaping the microbial community compositions across the four wells sampled. The model explained 55.3% of the variation in the microbial community compositions, which is higher than that reported earlier (see below). Of the explained variance, the groundwater chemistry and well jointly accounted for most of the variance (42.5%), indicating that both the microbial community composition and the groundwater chemistry have similar spatial structuring (Borcard et al. 1992), which is attributed to the influence of the landfill leachate (Abiriga et al. 2021b). Given that not all environmental variables are measurable in any single study, the unexplained variance (44.7%) may represent both the unmeasured deterministic and stochastic factors, although stochastic processes may play a partial role in shaping microbial community compositions (Stegen et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2014). We posit that in systems such as the present aquifer, which is under press perturbation (Zhou et al. 2014), deterministic processes are more important than stochastic processes. At present, the nature of the sampling design does not allow a full account of any mechanistic processes (variable selection, homogenous selection, dispersal limitation, etc.) to be drawn, as samples were taken from one level in each well. Yet, there is a significant vertical variation in the aquifer (see below). To ensure a full account for the entire aquifer, an in-depth analysis taking into consideration both the depth-wise (small scale) and longitudinal-wise (bigger scale) processes will be conducted and communicated in a future manuscript.

Earlier, we reported a lower explained variance with variation partitioning, 33.2% (Abiriga et al. 2021b) versus 55.3% in the present study. The difference is due to the present study being restricted to a single level in the aquifer while the previous study included all the multilevel sampling system in each well, which suggests that variation along the vertical axis is controlled by variables which we did not measure. This may be due to the inherent variation arising from the aquifer layering which may respond differently to changes in hydrologic regimes (Smith et al. 2018), resulting in differences in the microbial community compositions across the depths in the aquifer (Abiriga et al. 2021b). Sampling groundwater from only one level avoided this bottleneck. The small variance attributable to season (0.4%, Fig. 3) further indicates that seasonal variability due to differential response of aquifer layers to hydrologic regimes, which causes shifts in microbial communities (Pilloni et al. 2019), was minimal. This finding has a serious implication for future studies on subsurface microbiology, where a great deal of attention needs to be given in designing sampling for heterogeneous systems.

Conclusion

Our study shows taxa co-occurrence in four communities. Both the structure and complexity of the networks varied remarkable among the communities, which highlights inherent variations in composition and taxa interactions in situ. Similarly, the putative keystone taxa varied among the communities in composition as well as numerically. Putative biogeochemical cycling potentials of the keystone taxa include carbon cycling, nitrogen cycling, and phosphorous cycling which may suggest taxa cooperation, although taxa with potential for symbiosis and parasitism were also present. The study identified deterministic processes as the driving force shaping the microbial community assembly in the landfill-leachate-impacted aquifer, a finding further substantiated by employing variation partitioning, which indicated that the measured environmental variables explained most of the variation in the microbial community composition. The novelty of this research is the application of a combination of network analysis, ecological null model analysis, and multivariate statistics to microbial data from an environment which has not been previously studied for the ecological processes. Findings from this study should therefore advance our understanding of microbial community assembly in ecosystems subjected to press perturbations from landfill operations.

Availability of data and materials

The raw sequence data supporting the study have been deposited in Sequence Read Archive under BioProjects PRJNA677875 (Biosamples SAMN16775936-37, SAM16775944-45, SAM16775952-53, SAM16775958-59, and SAMN16775996-6019).

References

Abiriga D, Jenkins A, Alfsnes K, Vestgarden LS, Klempe H (2021a) Characterisation of the bacterial microbiota of a landfill-contaminated confined aquifer undergoing intrinsic remediation. Sci Total Environ 785:147349

Abiriga D, Jenkins A, Alfsnes K, Vestgarden LS, Klempe H (2021b) Spatiotemporal and seasonal dynamics in the microbial communities of a landfill-leachate contaminated aquifer. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 97(7):fiab086

Abiriga D, Jenkins A, Vestgarden LS, Klempe H (2021c) A nature-based solution to a landfill-leachate contamination of a confined aquifer. Sci Rep 11(1):1–12

Abiriga D, Vestgarden LS, Klempe H (2020) Groundwater contamination from a municipal landfill: effect of age, landfill closure, and season on groundwater chemistry. Sci Total Environ 737:140307

Abiriga D, Vestgarden LS, Klempe H (2021d) Long-term redox conditions in a landfill-leachate-contaminated groundwater. Sci Total Environ 755:143725

Anderson MJ (2001) A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol 26(1):32–46

Anderson MJ (2006) Distance-based tests for homogeneity of multivariate dispersions. Biometrics 62(1):245–253

Apprill A, McNally S, Parsons R, Weber L (2015) Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat Microb Ecol 75(2):129–137

Banerjee S, Schlaeppi K, van der Heijden MG (2018) Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat Rev Microbiol 16(9):567–576

Barberán A, Bates ST, Casamayor EO, Fierer N (2012) Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J 6(2):343–351

Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M (2009) Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks

Bjerg PL, Tuxen N, Reitzel LA, Albrechtsen HJ, Kjeldsen P (2011) Natural attenuation processes in landfill leachate plumes at three Danish sites. Groundwater 49(5):688–705

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F (2019) Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 37(8):852–857

Borcard D, Legendre P, Drapeau P (1992) Partialling out the spatial component of ecological variation. Ecology 73(3):1045–1055

Brown CT, Hug LA, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Castelle CJ, Singh A, Wilkins MJ, Wrighton KC, Williams KH, Banfield JF (2015) Unusual biology across a group comprising more than 15% of domain Bacteria. Nature 523(7559):208–211

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP (2016) DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 13(7):581

Castelle CJ, Brown CT, Anantharaman K, Probst AJ, Huang RH, Banfield JF (2018) Biosynthetic capacity, metabolic variety and unusual biology in the CPR and DPANN radiations. Nat Rev Microbiol 16(10):629–645

Christensen TH, Bjerg PL, Kjeldsen P (2000) Natural attenuation: a feasible approach to remediation of ground water pollution at landfills? Ground Water Monit Remed 20(1):69–77

Christensen TH, Kjeldsen P, Bjerg PL, Jensen DL, Christensen JB, Baun A, Albrechtsen H-J, Heron G (2001) Biogeochemistry of landfill leachate plumes. Appl Geochem 16(7-8):659–718

Csardi G, Nepusz T (2006) The igraph software package for complex network research. Int J Complex Syst 1695(5):1–9

de Vries FT, Griffiths RI, Bailey M, Craig H, Girlanda M, Gweon HS, Hallin S, Kaisermann A, Keith AM, Kretzschmar M (2018) Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat Commun 9(1):1–12

Eggen T, Moeder M, Arukwe A (2010) Municipal landfill leachates: a significant source for new and emerging pollutants. Sci Total Environ 408(21):5147–5157

Erdős P, Rényi A (1960) On the evolution of random graphs. Publ Math Inst Hung Acad Sci 5(1):17–60

Fadrosh DW, Ma B, Gajer P, Sengamalay N, Ott S, Brotman RM, Ravel J (2014) An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2(1):6

Faust K, Raes J (2012) Microbial interactions: from networks to models. Nat Rev Microbiol 10(8):538–550

Fuhrman JA (2009) Microbial community structure and its functional implications. Nature 459(7244):193–199

Gotelli NJ, Hart EM, Ellison AM (2015) EcoSimR: null model analysis for ecological data. R package version 0.1.0. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16522http://github.com/gotellilab/EcoSimR

Griebler C, Lueders T (2009) Microbial biodiversity in groundwater ecosystems. Freshw Biol 54(4):649–677

Griebler C, Malard F, Lefébure T (2014) Current developments in groundwater ecology—from biodiversity to ecosystem function and services. Curr Opin Biotechnol 27:159–167

Guo B, Zhang L, Sun H, Gao M, Yu N, Zhang Q et al (2022) Microbial co-occurrence network topological properties link with reactor parameters and reveal importance of low-abundance genera. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 8(1):1–13

Herrmann M, Wegner C-E, Taubert M, Geesink P, Lehmann K, Yan L, Lehmann R, Totsche KU, Küsel K (2019) Predominance of Cand. Patescibacteria in groundwater is caused by their preferential mobilization from soils and flourishing under oligotrophic conditions. Front Microbiol 10:1407

Herzyk A, Fillinger L, Larentis M, Qiu S, Maloszewski P, Hünniger M, Schmidt SI, Stumpp C, Marozava S, Knappett PS (2017) Response and recovery of a pristine groundwater ecosystem impacted by toluene contamination–a meso-scale indoor aquifer experiment. J Contam Hydrol 207:17–30

Horner-Devine MC, Silver JM, Leibold MA, Bohannan BJ, Colwell RK, Fuhrman JA, Green JL, Kuske CR, Martiny JB, Muyzer G (2007) A comparison of taxon co-occurrence patterns for macro-and microorganisms. Ecology 88(6):1345–1353

Ju F, Xia Y, Guo F, Wang Z, Zhang T (2014) Taxonomic relatedness shapes bacterial assembly in activated sludge of globally distributed wastewater treatment plants. Environ Microbiol 16(8):2421–2432

Kantor RS, Wrighton KC, Handley KM, Sharon I, Hug LA, Castelle CJ, Thomas BC, Banfield JF (2013) Small genomes and sparse metabolisms of sediment-associated bacteria from four candidate phyla. MBio 4(5):e00708–e00713

Kjeldsen P, Barlaz MA, Rooker AP, Baun A, Ledin A, Christensen TH (2002) Present and long-term composition of MSW landfill leachate: a review. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 32(4):297–336

Klempe H (2004) Identification of Quaternary subsurface glacial deposits using 3D databases and GIS. Nor Geogr Tidsskr 58(2):90–95

Klempe H (2015) The hydrogeological and cultural background for two sacred springs, Bø, Telemark County, Norway. Quat Int 368:31–42

Konopka A, Lindemann S, Fredrickson J (2015) Dynamics in microbial communities: unraveling mechanisms to identify principles. ISME J 9(7):1488–1495

Lane D (1991) 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. Wiley, Chichester

Legendre P, Gallagher ED (2001) Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 129(2):271–280

Liu C, Cui Y, Li X, Yao M (2021) microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 97(2):fiaa255

Lu Z, He Z, Parisi VA, Kang S, Deng Y, Van Nostrand JD, Masoner JR, Cozzarelli IM, Suflita JM, Zhou J (2012) GeoChip-based analysis of microbial functional gene diversity in a landfill leachate-contaminated aquifer. Environ Sci Technol 46(11):5824–5833

Lupatini M, Suleiman AK, Jacques RJ, Antoniolli ZI, de Siqueira Ferreira A, Kuramae EE, Roesch LF (2014) Network topology reveals high connectance levels and few key microbial genera within soils. Front Environ Sci 2:10

Masoner JR, Kolpin DW, Cozzarelli IM, Smalling KL, Bolyard SC, Field JA, Furlong ET, Gray JL, Lozinski D, Reinhart D (2020) Landfill leachate contributes per-/poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and pharmaceuticals to municipal wastewater. Environ Sci Water Res Technol 6(5):1300–1311

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S (2013) phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8(4):e61217

Miller AD, Roxburgh SH, Shea K (2011) How frequency and intensity shape diversity–disturbance relationships. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108(14):5643–5648

Moody CM, Townsend TG (2017) A comparison of landfill leachates based on waste composition. Waste Manag 63:267–274

Mouser PJ, Rizzo DM, Röling WF, van Breukelen BM (2005) A multivariate statistical approach to spatial representation of groundwater contamination using hydrochemistry and microbial community profiles. Environ Sci Technol 39(19):7551–7559

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F.G., Friendly, M., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., McGlinn, D., Minchin, PR; O’Hara R.B., Simpson G. L.; Solymos P., Stevens M.H. H.; Szoecs E., Wagner H. (2019) vegan: community ecology package, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Pascual J, Foesel BU, Geppert A, Huber KJ, Boedeker C, Luckner M, Wanner G, Overmann J (2018) Roseisolibacter agri gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel slow-growing member of the under-represented phylum Gemmatimonadetes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 68(4):1028–1036

Pilloni G, Bayer A, Ruth-Anneser B, Fillinger L, Engel M, Griebler C, Lueders T (2019) Dynamics of hydrology and anaerobic hydrocarbon degrader communities in a tar-oil contaminated aquifer. Microorganisms 7(2):46

Rajasekar A, Sekar R, Medina-Roldan E, Bridge J, Moy CK, Wilkinson S (2018) Next-generation sequencing showing potential leachate influence on bacterial communities around a landfill in China. Can J Microbiol 64(8):537–549

R-Core-Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna https://www.R-project.org/

Smith HJ, Zelaya AJ, De León KB, Chakraborty R, Elias DA, Hazen TC, Arkin AP, Cunningham AB, Fields MW (2018) Impact of hydrologic boundaries on microbial planktonic and biofilm communities in shallow terrestrial subsurface environments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94(12):fiy191

Song H-S, Renslow RS, Fredrickson JK, Lindemann SR (2015a) Integrating ecological and engineering concepts of resilience in microbial communities. Front Microbiol 6:1298

Song L, Wang Y, Zhao H, Long DT (2015b) Composition of bacterial and archaeal communities during landfill refuse decomposition processes. Microbiol Res 181:105–111

Staley BF, Francis L, Wang L, Barlaz MA (2018) Microbial ecological succession during municipal solid waste decomposition. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102(13):5731–5740

Stegen JC, Lin X, Konopka AE, Fredrickson JK (2012) Stochastic and deterministic assembly processes in subsurface microbial communities. ISME J 6(9):1653–1664

Svensson JR, Lindegarth M, Jonsson PR, Pavia H (2012) Disturbance–diversity models: what do they really predict and how are they tested? Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 279(1736):2163–2170

Taş N, Brandt BW, Braster M, van Breukelen BM, Röling WF (2018) Subsurface landfill leachate contamination affects microbial metabolic potential and gene expression in the Banisveld aquifer. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94(10):fiy156

Williams RJ, Howe A, Hofmockel KS (2014) Demonstrating microbial co-occurrence pattern analyses within and between ecosystems. Front Microbiol 5:358

Winkler LW (1888) Die bestimmung des im wasser gelösten sauerstoffes. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges 21(2):2843–2854

Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Miller CS, Castelle CJ, VerBerkmoes NC, Wilkins MJ, Hettich RL, Lipton MS, Williams KH (2012) Fermentation, hydrogen, and sulfur metabolism in multiple uncultivated bacterial phyla. Science 337(6102):1661–1665

Zainun MY, Simarani K (2018) Metagenomics profiling for assessing microbial diversity in both active and closed landfills. Sci Total Environ 616:269–278

Zhang H, Sekiguchi Y, Hanada S, Hugenholtz P, Kim H, Kamagata Y, Nakamura K (2003) Gemmatimonas aurantiaca gen. nov., sp. nov., a Gram-negative, aerobic, polyphosphate-accumulating micro-organism, the first cultured representative of the new bacterial phylum Gemmatimonadetes phyl. nov. J Med Microbiol 53(4):1155–1163

Zhao R, Feng J, Yin X, Liu J, Fu W, Berendonk TU, Zhang T, Li X, Li B (2018) Antibiotic resistome in landfill leachate from different cities of China deciphered by metagenomic analysis. Water Res 134:126–139

Zhou J, Deng Y, Zhang P, Xue K, Liang Y, Van Nostrand JD, Yang Y, He Z, Wu L, Stahl DA (2014) Stochasticity, succession, and environmental perturbations in a fluidic ecosystem. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(9):E836–E845

Acknowledgements

We thank Frode Bergan and Tom Aage Aarnes for helping in fieldwork and Karin Brekke Li for technical assistance in chemical analysis of groundwater samples. The sequencing service was provided by the Norwegian Sequencing Centre (https://www.sequencing.uio.no), a national technology platform hosted by the University of Oslo and supported by the Functional Genomics and Infrastructure programs of the Research Council of Norway and the Southeastern Regional Health Authorities. We thank Dr. Alfsnes Kristian for assisting with the bioinformatics. An earlier version of this manuscript was published in the PhD thesis of Daniel Abiriga submitted to the University of South-Eastern Norway (https://openarchive.usn.no/usn-xmlui/handle/11250/2827236).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daniel Abiriga, Andrew Jenkins, and Harald Klempe contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Daniel Abiriga. Statistical data analysis was performed by Daniel Abiriga. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Daniel Abiriga and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Changes in Shannon diversity index between 2018 and 2019 and between autumn and spring, based on unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Significant differences are indicated in bold font face. R0: background well; R104: proximal well; R203: intermediate well; R403: distal well. Table S2. The characteristics of the groundwater geochemistry for the period 2018-2019. The data are average values (N = 12). All values are in mg/l, unless otherwise stated. Table S3. The library statistics, showing the number of reads. Figure S1. Correlation between the rarefied and observed taxa richness (left panel) and rarefaction curves for the samples (right panel). Table S4. Putative keystone taxa in the background (R0) well based on node degree and betweenness topological properties (node degree >2, and betweenness centrality ≥ 10). Figure S2. Zi-Pi plot of the individual taxa from the network of the background (R0) well community. Table S5. Putative keystone taxa in the proximal (R104) well based on node degree and betweenness topological properties (node degree ≥ 10, and betweenness centrality ≥ 50). Figure S3. Zi-Pi plot of the individual taxa from the network of the proximal (R104) well community. A node (taxon) belonging to phylum Chloroflexi (Pi = 0.595) is close to being a connector node in the network. Table S6. Putative keystone taxa in the proximal (R203) well based on node degree and betweenness topological properties (node degree ≥ 7, and betweenness centrality ≥ 39). Figure S4. Zi-Pi plot of the individual taxa from the network of the intermediate (R203) well community. Nitrospira (Pi = 0.625) in the phylum Nitrospirota is designated as a connector node. Nitrosomonadaceae (Pi = 0.611) in phylum Proteobacteria is at border to being another connector node in the network. Table S7. Putative keystone taxa (Node degree > 1) in the distal (R402) well. Figure S5. Zi-Pi plot of the individual taxa from the network of the distal (R402) well community. Figure S6. Taxa that may be of special interest in microbial species interactions. The abundance data are for the period 2018-2019. R0: background well; R104: proximal well; R203: intermediate well; R403: distal well.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abiriga, D., Jenkins, A. & Klempe, H. Microbial assembly and co-occurrence network in an aquifer under press perturbation. Ann Microbiol 72, 41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13213-022-01698-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13213-022-01698-0