Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular health has been associated with dementia onset, but little is known about the variation of such association by sex and age considering dementia subtypes. We assessed the role of sex and age in the association between cardiovascular risk and the onset of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia in people aged 50–74 years.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study covering 922.973 Catalans who attended the primary care services of the Catalan Health Institute (Spain). Data were obtained from the System for the Development of Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP database). Exposure was the cardiovascular risk (CVR) at baseline categorized into four levels of Framingham-REGICOR score (FRS): low (FRS < 5%), low-intermediate (5% ≤ FRS < 7.5%), high-intermediate (7.5% ≤ FRS < 10%), high (FRS ≥ 10%), and one group with previous vascular disease. Cases of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were identified using validated algorithms, and cases of vascular dementia were identified by diagnostic codes. We fitted stratified Cox models using age parametrized as b-Spline.

Results

A total of 51,454 incident cases of all-cause dementia were recorded over a mean follow-up of 12.7 years. The hazard ratios in the low-intermediate and high FRS groups were 1.12 (95% confidence interval: 1.08–1.15) and 1.55 (1.50–1.60) for all-cause dementia; 1.07 (1.03–1.11) and 1.17 (1.11–1.24) for Alzheimer’s disease; and 1.34 (1.21–1.50) and 1.90 (1.67–2.16) for vascular dementia. These associations were stronger in women and in midlife compared to later life in all dementia types. Women with a high Framingham-REGICOR score presented a similar risk of developing dementia — of any type — to women who had previous vascular disease, and at age 50–55, they showed three times higher risk of developing dementia risk compared to the lowest Framingham-REGICOR group.

Conclusions

We found a dose‒response association between the Framingham-REGICOR score and the onset of all dementia types. Poor cardiovascular health in midlife increased the onset of all dementia types later in life, especially in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients with cardiovascular disease are at higher risk of developing dementia [1, 2]. Emerging evidence suggests that the control of cardiovascular risk could help prevent dementia even in persons without cardiovascular disease [3]. Some validated cardiovascular risk scores (i.e., Framingham or Life Simple 7) have been associated with the development of all-cause dementia [4,5,6]; but little is known about this association considering dementia subtypes [4].

Age and sex are risk factors for both cardiovascular diseases and dementia; hence, they may play a role in the association between these two conditions. Regarding age, some studies reported significant associations between cardiovascular risk scores and incident dementia in both midlife and late life [7, 8], but other analyses found significant associations only in midlife [6]. Thus, the role of age in the association between cardiovascular risk and dementia remains unclear, as do the variations of such influence by sex, which are of particular interest.

Few studies have provided analyses by sex and they reported inconsistent findings on the association between cardiovascular risk score and cognitive function or dementia: the Whitehall II study reported a stronger association in men [9] and the SALSA study in women [10]; the Rush Memory and Aging Project found similar results between sexes [4]. The Framingham Heart Study assessed the role of both sex and age in the relationship between individual cardiovascular risk factors and onset of overall dementia. Nevertheless, the small sample size precluded consistent conclusions, and the authors recommended further investigation on the role of sex in larger cohorts [6]. Large sample sizes for the study of dementia can be obtained from clinical databases of electronic health records routinely collected in primary care which have been reported to be accurate in identifying dementia cases [11, 12].

We used data from a large primary care database to assess the role of sex and age in the association between cardiovascular risk and the onset of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia.

Methods

We designed a retrospective cohort study that included all dementia-free individuals registered in the System for the Development of Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP) aged 50 to 74 years who attended the primary care services up to one year prior to the entry date (further details on exclusion criteria in Box S1). The SIDIAP is a valid and reliable database that contains longitudinal health records from about 6 million persons who attended the primary care services of the Catalan Health Institute (12% of the Spanish population and 80% of the Catalan population) [13]. The SIDIAP database contains comprehensive demographic information, clinical diagnoses (coded with the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM)), treatments (coded with the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification code, ATC), referrals, and hospitalizations. The SIDIAP data are representative of the Catalan population [14], and the records on cardiovascular risk factors and diseases [15], dementia [12], and Alzheimer’s disease [16] have been validated.

The recruitment period was from January 1 until December 31, 2008. The entry date was the first day of the participants’ month of birth. Follow-up lasted until the earliest of the following events: dementia, death, moving out to a region that was not covered by SIDIAP, or end of the study period — December 31, 2022.

The exposure was the level of cardiovascular risk at baseline. Patients with previous vascular diseases were included in the highest risk category (Box S2). Participants free of cardiovascular disease at baseline were classified in four groups according to their Framingham-REGICOR score (Fig. S1): low (score < 5%), low-intermediate (5% ≤ score < 7.5%), high-intermediate (7.5% ≤ score < 10%), and high (score ≥ 10%). The Framingham-REGICOR is the Spanish-calibrated adaptation of the Framingham score; it is valid and reliable for the population without previous cardiovascular disease aged between 35 and 74 years [17]. The Framingham-REGICOR score combines several variables (age, sex, smoking, type-2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), systolic and diastolic blood pressure) to estimate the 10-year risk of developing a fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction, silent myocardial infarction, or angina pectoris [17].

The outcomes were incident cases of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease — both identified by validated algorithms [12, 16] — and of vascular dementia identified using diagnostic codes (Box S3). We considered the following covariates at baseline: age; sex; rurality; (rural/urban); measurements of weight, height, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and HDL, triglycerides; diagnosis of DM2, hyperthyroidism, alcohol-related disorders, Parkinson’s disease, and depression; smoking (smoker/non-smoker) and obesity (obese/non-obese) (Box S4).

Statistical analyses

Continuous and categorical variables were described with the mean (standard deviation, SD) and counts (percentages, %), respectively. We used 10 multiple imputations by chained equations [18] to replace the missing baseline values of total cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, blood pressure, weight, and height (Box S5). We estimated the crude incidences for each type of dementia and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) assuming a Poisson distribution. Estimates were disaggregated by risk group, sex, or age where appropriate.

We used stratified Cox survival models that allowed us to assess predictors (age or Framingham-REGICOR) even if they did not satisfy the proportional hazard assumptions by adjusting for the baseline hazard function of each stratum (in our study, age groups: 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74 years) [19]. First, we fitted stratified Cox models by age and sex, and considered follow-up as an underlying timescale. We built one model for each outcome adjusted by obesity [20], alcohol related disorders [21], rurality [22], hyperthyroidism [23], and depression [24]. The interaction between the Framingham-REGICOR score and sex was tested.

Then, we replicated the stratified Cox models including an interaction between the Framingham-REGICOR score, sex, and age to estimate the hazard ratios (HR) for the dementia outcomes per year of age; age was parameterized as a b-Spline [25]. Interactions between age, sex, and Framingham-REGICOR score were assessed using likelihood ratio tests. In all models, we considered the minimum baseline risk group as reference.

As sensitivity analyses, we calculated unadjusted models; we also replicated models using the case-complete dataset and used the imputed dataset with censoring at the first-ever dementia or cardiovascular disease record during follow-up. Finally, we calculated Fine-Gray multivariate models to assess a potential competing risk with death. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the R software, version 4.3.0, and we used the MICE package for multiple imputation [26, 27].

Results

We identified 1,200,700 persons and 922,973 of them fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Fig. S1). The average follow-up time was 12.7 years (SD = 3.1). A comparison of the complete cases and imputed datasets showed similar mean values regarding the imputed variables (Table S1).

The study participants were mainly women (59.9%), from urban areas, with a mean age of 61.7 years. The baseline characteristics and exposure groups, overall and by sex, are described in Table S2. The Framingham-REGICOR estimates were higher in men (Table S2). The low and low-intermediate risk groups included 92.3% of women and 69.1% of men; whereas the high-intermediate and high-risk groups included 3.6% of women and 19.5% of men (Table 1). Women presented worse lipid profile, higher blood pressure levels, and higher prevalence of hypertension, DM2, and obesity compared to men in all the Framingham-REGICOR groups (Table 1). Only smoking and alcohol-related disorders were more prevalent in men (Table 1). The age increment with the increase of Framingham-REGICOR risk was more pronounced in men: the mean age between the low and the high exposure groups increased 8.9 years in men, and 2.5 years in women (Table 1).

During follow-up, we identified 51,454 cases of all-cause dementia, 32,440 of Alzheimer’s disease, and 4716 of vascular dementia. The crude incidence rates were 4.46/1,000 person-years (95% CI: 4.45–4.47) for all-cause dementia, 2.79/1000 person-years (95% CI: 2.78–2.81) for Alzheimer’s disease, and 0.40/1000 person-years (95% CI: 0.39–0.41) for vascular dementia. Within each age category, the crude incidence rates tended to increase with the baseline cardiovascular risk, and these increments tended to be more evident in women than in men for all-cause dementia (Table 2) and subtypes (Tables S3–S4).

Stratified Cox models showed a dose–response association between cardiovascular risk and dementia onset: the higher the categorized Framingham-REGICOR risk at baseline, the higher the risk of developing all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia (Table 3). The interactions between the Framingham-REGICOR score and sex were significant for all-cause dementia (p < 0.001) and vascular dementia (p = 0.02) but not for Alzheimer’s disease (p = 0.25). Disaggregated results by sex are shown in Table 3.

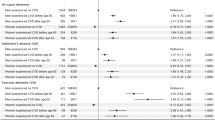

Spline models showed that the association between cardiovascular risk and dementia differed by age and sex (Figs. 1, 2, and 3); the p-value for the interaction was < 0.001 in all outcomes. In midlife, significant associations were stronger than in later life; and were more noticeable in women than in men (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). In women, cardiovascular risk is associated with dementia in all the exposure groups and dementia outcomes. But men only showed significant associations in the highest cardiovascular risk groups and regarding all-cause and vascular dementia (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). The significant HRs were clearly higher in women; for example, in people aged 53 years with high cardiovascular risk, the HR of all-cause dementia was 3.16 in women, and 1.79 in men. Moreover, women with a high Framingham-REGICOR score presented a similar risk of developing dementia — of any type — to women who had previous vascular disease (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). Finally, the age at which the HR remained significant was older in women than in men (Figs. 1, 2, and 3); for example, in the group with high cardiovascular risk, the HR for all-cause dementia were significant in women aged between 51 and 74 years, and in men aged between 53 and 68 years. The sensitivity analyses presented similar results (Figs. S2–S4, Table S5).

Discussion

This mega-cohort study of about 1 million people and > 50,000 dementia cases based on routinely collected data from the primary care services provides a novel contribution: it shows a dose–response association between the Framingham-REGICOR score and the incidence of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia. This dose–response association was stronger in midlife and attenuated in later life, and more pronounced in women than in men. Women with a high Framingham-REGICOR score presented a similar risk of developing dementia — of any type — to women who had previous vascular disease; and at age 50–55, they showed three times higher risk of developing dementia than the lowest exposure group.

Comparison with existing literature

We found that the highest risk of developing dementia later in life was at 50–55 years of age, and it decreased at older ages, in line with previous studies [6,7,8]. In fact, the pathological changes that lead to dementia onset might start decades before the clinical manifestations of cognitive impairment and dementia [28]. Regarding the potential role of cardiovascular risk factors on dementia, poor cardiovascular health at age 50 has been related with increased risk of dementia and brain volume 20 years later [5]. We observed an attenuated association between Framingham-REGICOR at older ages and later dementia onset, which could be consistent with reverse causation. Dementia symptoms are preceded by a preclinical phase (of about 20–30 years) during which levels of cardiovascular risk factors could decrease, resulting in an attenuation or even a reverse association between Framingham-REGICOR and dementia [29,30,31]. In this scenario, lower levels of cardiovascular risk factors at older ages would be a consequence of preclinical disease rather than a cause of dementia [5, 29].

Our results emphasize a sex-dependent association between the Framingham-REGICOR score and dementia onset. We observed that significant hazard ratios were higher and occurred until older ages in women, in all exposure groups. These results align with previous descriptions of a stronger association between cardiovascular risk scores and cognitive function [32, 33] or dementia [10] in women. However, two analyses found a similar association in both sexes [4, 5]. Their limited sample size could have hindered the detection of a significant association when assessing the effect of sex [4]. The observed sex differences in our study could be explained by the following reasons. First, we observed poorer cardiovascular health in women; within a given exposure group, women tended to have worse levels of total cholesterol, HDL-C, and a higher prevalence of hypertension, DM2, and obesity. These findings agree with previous studies that reported worse control of several cardiovascular risk factors in women [34]. In contrast, we observed that Framingham-REGICOR score increased with age in men, but not in women. Thus, aging might be a strong confounder of the association between Framingham-REGICOR and dementia in men. Second, the role of the individual cardiovascular risk factors on the dementia risk may differ by sex. Several studies reported a higher susceptibility in women to the effects of midlife elevated blood pressure [35, 36] or DM2 [6, 37, 38], which increased the risk of dementia. In our study, hypertension and DM2 were highly prevalent among women in most of the exposure groups; for example, in the high-risk group, the prevalence of DM2 reached 90.8% in women and 46.1% in men. In Catalonia, women with diabetes have shown worse target control than men [39, 40]. Moreover, the strongest impact of DM2 in women occurred in midlife and persisted after age 80 [6]. In our sample, women with intermediate or high cardiovascular risk were 63 years old on average; thus, in most of them, DM2 might still have a long time to contribute to dementia onset. Third, differences in genetics, hormones, structural brain development, or functional connectivity between men and women could contribute to the sex-related association between cardiovascular health and dementia we observed [37, 41]. Finally, certain gender roles might also contribute to the increased risk in women. Older women may not have had as many opportunities to receive a higher level of education or to do physical exercise as men, or they deliver caregiving tasks more frequently than men — these three aspects have been described as risk factors for both dementia [41] and cardiovascular disease [42].

Regarding dementia subtypes, we observed that cardiovascular risk was associated with vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, in line with previous studies [4, 43,44,45]. The associations were stronger with vascular dementia; these are expected results because the main risk factors for vascular dementia are included in the REGICOR-Framingham score. Regarding Alzheimer’s disease, the vascular component is less evident; genetics plays an important role in the disease risk profile and may interact with the association between cardiovascular risk and dementia [4].

Implications for practice and research

Overall, our findings suggest that general practitioners could use sex- and age-specific cardiovascular risk scores to convey the risk of developing dementia and recommend healthier lifestyles that could harness it. Our results indicate that middle-aged adults may be the target population: middle-aged men with Framingham-REGICOR scores ≥ 10, middle-aged women with Framingham-REGICOR scores ≥ 5, and patients with vascular disease. From a public health perspective, minor improvements in the cardiovascular risk score among women at low or intermediate risk could represent a big impact on preventing dementia at a population level. The provided sex-specific recommendations may help prevent gender biases when diagnosing or treating cardiovascular risk factors [46]. To researchers, the use of sex-specific cardiovascular risk scores may help integrate a necessary sex and gender perspective in future studies on the relationship between cardiovascular health and dementia.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was the high external validity grounded on a large sample size and 15 years of follow-up, which is longer than that in previous studies [10, 43, 45]. Moreover, the analysis of electronic health records allows the study of real-life clinical conditions and precludes a selection bias due to low response rates or losses during follow-up, which could be common among people with dementia. The internal validity in this study was ensured through the use of validated records of cardiovascular risk factors [15], overall dementia [12], and Alzheimer’s disease [16].

We also acknowledge several limitations. First, there could be some residual confounding due to unobserved variables that were not available in SIDIAP, such as educational level [47] or physical activity [43]. Second, under-registration of certain health records might promote selection bias, but we mitigated this limitation by imputing the missing data. Finally, the vascular dementia records were not validated, but the observed dose–response association between the REGICOR-Framingham score and vascular dementia may indicate a reasonable accuracy of the diagnoses.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight that the Framingham-REGICOR scores are associated with the incidence of overall dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia, in a dose-dependent way. The presence of a dose–response association between cardiovascular risk score and dementia onset is compatible with causality. This association is stronger in midlife, attenuated in older ages, and more pronounced in women. Women with high estimates of the Framingham-REGICOR score presented a risk of developing dementia similar to women with a history of cardiovascular disease. We would recommend that general practitioners use sex-and-age-specific scores to assess cardiovascular risk to prevent dementia, and public health managers incorporate gender perspective into the policies to improve cardiovascular health in midlife and prevent dementia later in life.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to legal reasons related to data privacy protection but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CVR:

-

Cardiovascular risk

- SIDIAP:

-

System for the Development of Research in Primary Care

- ICD-10-CM:

-

International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification code

- DM2:

-

Type-2 diabetes mellitus

References

Dong C, Zhou C, Fu C, Hao W, Ozaki A, Shrestha N, et al. Sex differences in the association between cardiovascular diseases and dementia subtypes: a prospective analysis of 464,616 UK Biobank participants. Biol Sex Differ. 2022;13:21.

de Bruijn RF, Ikram MA. Cardiovascular risk factors and future risk of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med. 2014;12:130.

Peters R, Booth A, Rockwood K, Peters J, D’Este C, Anstey KJ. Combining modifiable risk factors and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e022846.

Song R, Pan KY, Xu H, Qi X, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk burden with risk of dementia and brain pathologies: a population-based cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:1914 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34310004/).

Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, Schnitzler A, Empana J-P, Ebmeier KP, et al. Association of ideal cardiovascular health at age 50 with incidence of dementia: 25 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ. 2019;366:l4414.

McGrath ER, Beiser AS, O’Donnell A, Himali JJ, Pase MP, Satizabal CL, et al. Determining Vascular Risk Factors for Dementia and Dementia Risk Prediction Across Mid- to Later-Life: The Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2022;99:e142. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200521.

Wu J, Xiong Y, Xia X, Orsini N, Qiu C, Kivipelto M, et al. Can dementia risk be reduced by following the American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7? A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;83:101788.

Liang Y, Ngandu T, Laatikainen T, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J, Kivipelto M, et al. Cardiovascular health metrics from mid- to late-life and risk of dementia: a population-based cohort study in Finland. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003474.

Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Nabi H, Batty GD, Brunner E, Kivimäki M, et al. Predictive utility of the Framingham general cardiovascular disease risk profile for cognitive function: evidence from the Whitehall II study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2326–32.

Hazzouri AZA, Haan MN, Neuhaus JM, Pletcher M, Peralta CA, López L, et al. Cardiovascular risk score, cognitive decline, and dementia in older mexican americans: the role of sex and education. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004978.

Wilkinson T, Ly A, Schnier C, Rannikmäe K, Bush K, Brayne C, et al. Identifying dementia cases with routinely collected health data: a systematic review. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2018;14:1038–51.

Ponjoan A, Garre-Olmo J, Blanch J, Fages E, Alves-Cabratosa L, Martí-Lluch R, et al. Epidemiology of dementia: prevalence and incidence estimates using validated electronic health records from primary care. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;4:217–28.

Recalde M, Rodríguez C, Burn E, Far M, García D, Carrere-Molina J, et al. Data Resource Profile: the Information System for Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP). Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:e324–36.

García-Gil M del M, Hermosilla E, Prieto-Alhambra D, Fina F, Rosell M, Ramos R, et al. Construction and validation of a scoring system for the selection of high-quality data in a Spanish population primary care database (SIDIAP). Inform Prim Care. 2011;19:135–45.

Ramos R, Balló E, Marrugat J, Elosua R, Sala J, Grau M, et al. Validity for use in research on vascular diseases of the SIDIAP (Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care): the EMMA study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65:29–37.

Ponjoan A, Garre-Olmo J, Blanch J, Fages E, Alves-Cabratosa L, Martí-Lluch R, et al. How well can electronic health records from primary care identify Alzheimer’s disease cases? Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:509–18.

Marrugat J, D’Agostino R, Sullivan L, Elosua R, Wilson P, Ordovas J, et al. An adaptation of the Framingham coronary heart disease risk function to European Mediterranean areas. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:634–8.

Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2009;338:b2393.

Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival analysis: a self-learning text. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2005.

Qu Y, Hu H-Y, Ou Y-N, Shen X-N, Xu W, Wang Z-T, et al. Association of body mass index with risk of cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;115:189–98.

Rehm J, Hasan OSM, Black SE, Shield KD, Schwarzinger M. Alcohol use and dementia: a systematic scoping review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11:1.

Fages-Masmiquel E, Ponjoan A, Blanch J, Alves-Cabratosa L, Martí-Lluch R, Comas-Cufí M, et al. The effect of age and sex on factors associated with dementia. Rev Neurol. 2021;73:409–15.

Ma L-Y, Zhao B, Ou Y-N, Zhang D-D, Li Q-Y, Tan L. Association of thyroid disease with risks of dementia and cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1137584.

Santabarbara J, Sevil-Perez A, Olaya B, Gracia-Garcia P, Lopez-Anton R. Clinically relevant late-life depression as risk factor of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Rev Neurol. 2019;68:493–502.

Wang W, Yan J. Shape-Restricted Regression Splines with R Package splines2. J Data Sci. 2021;19:498–517.

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Soft. 2011;45:1–67.

R Development Core Team. R: A language and enviroment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/

Jansen WJ, Ossenkoppele R, Knol DL, Tijms BM, Scheltens P, Verhey FRJ, et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:1924–38.

Kivimäki M, Luukkonen R, Batty GD, Ferrie JE, Pentti J, Nyberg ST, et al. Body mass index and risk of dementia: analysis of individual-level data from 1.3 million individuals. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:601–9.

Abell JG, Kivimäki M, Dugravot A, Tabak AG, Fayosse A, Shipley M, et al. Association between systolic blood pressure and dementia in the Whitehall II cohort study: role of age, duration, and threshold used to define hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3119–25.

Hessler JB, Ander K-H, Brönner M, Etgen T, Förstl H, Poppert H, et al. Predicting dementia in primary care patients with a cardiovascular health metric: a prospective population-based study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:116.

Laughlin GA, McEvoy LK, von Mühlen D, Daniels LB, Kritz-Silverstein D, Bergstrom J, et al. Sex differences in the association of Framingham Cardiac Risk Score with cognitive decline in community-dwelling elders without clinical heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:683–9.

Tarraf W, Kaplan R, Daviglus M, Gallo LC, Schneiderman N, Penedo FJ, et al. Cardiovascular Risk and Cognitive Function in Middle-Aged and Older Hispanics/Latinos: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;73:103–16.

de Ritter R, Sep SJS, van der Kallen CJH, Schram MT, Koster A, Kroon AA, et al. Adverse differences in cardiometabolic risk factor levels between individuals with pre-diabetes and normal glucose metabolism are more pronounced in women than in men: the Maastricht Study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2019;7:e000787.

Gilsanz P, Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Mungas DM, DeCarli C, et al. Female sex, early-onset hypertension, and risk of dementia. Neurology. 2017;89:1886–93.

Gong J, Harris K, Peters SAE, Woodward M. Sex differences in the association between major cardiovascular risk factors in midlife and dementia: a cohort study using data from the UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2021;19:110.

Huo N, Vemuri P, Graff-Radford J, Syrjanen J, Machulda M, Knopman DS, et al. Sex Differences in the Association between Midlife Cardiovascular Conditions or Risk Factors with Midlife Cognitive Decline. Neurology. 2022;98:E623–32.

Tanaka M, Imano H, Hayama-Terada M, Muraki I, Shirai K, Yamagishi K, et al. Sex- and age-specific impacts of smoking, overweight/obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus in the development of disabling dementia in a Japanese population. Environ Health Prev Med. 2023;28:11.

Cambra K, Galbete A, Forga L, Lecea O, Ariz MJ, Moreno-Iribas C, et al. Sex and age differences in the achievement of control targets in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from a population-based study in a South European region. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:1–7.

Galbete A, Cambra K, Forga L, Baquedano FJ, Aizpuru F, Lecea O, et al. Achievement of cardiovascular risk factor targets according to sex and previous history of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. J Diabetes Complications. 2019;33:107445.

Volgman AS, Bairey Merz CN, Aggarwal NT, Bittner V, Bunch TJ, Gorelick PB, et al. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Disease and Cognitive Impairment: Another Health Disparity for Women? J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013154.

Vogel B, Acevedo M, Appelman Y, Bairey Merz CN, Chieffo A, Figtree GA, et al. The Lancet women and cardiovascular disease Commission: reducing the global burden by 2030. Lancet. 2021;397:2385–438.

Cho S, Yang P-S, Kim D, You SC, Sung J-H, Jang E, et al. Association of cardiovascular health with the risk of dementia in older adults. Sci Rep. 2022;12:15673.

Li SS, Zheng J, Mei B, Wang HY, Zheng M, Zheng K. Correlation study of Framingham risk score and vascular dementia: an observational study. Medicine (United States). 2017;96:e8387.

Klages JD, Fisk JD, Rockwood K. APOE genotype, vascular risk factors, memory test performance and the five-year risk of vascular cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:292–7.

Skvortsova A, Meeuwis SH, Vos RC, Vos HMM, van Middendorp H, Veldhuijzen DS, et al. Implicit gender bias in the diagnosis and treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized online study. Diabet Med. 2023;40:e15087.

Sharp ES, Gatz M. Relationship between education and dementia: an updated systematic review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:289–304.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the Carlos III Health Institute (PI20/01239) and was supported by the Agency for Management of University and Research Grants – AGAUR (grant number 2021 SGR 1473), and the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain), awarded on the call for the creation of Health Outcomes Oriented Cooperative Research Networks (RICORS), with reference (RD21/0016/0001), co-funded with European Union – Next Generation EU funds. Ester Fages-Masmiquel received a pre-doctoral grant from the Fundació Institut Universitari per a la recerca a l'Atenció Primària de Salut Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAPJGol) (nº 7Z18/019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP, RR, and MGG participated in the conceptualization and study design. GDA and FRA participated in the data acquisition. JB and LZP conducted the data management and statistical analyses. EF, RML and RR lead the interpretation of the results. AP and LAC wrote the first manuscript draft. All authors revised and contributed to improve several drafts. Finally, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research from the Fundació Institut Universitari per a la recerca a l’Atenció Primària de Salut Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAPJGol) (code: 21/197-P). This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Written informed consent was not required because patients were not involved. All data were obtained from the SIDIAP database which contains pseudo-anonymized longitudinal medical records routinely collected in primary care settings. In the SIDIAP database, confidentiality is rigorously assured by a standardized system of codification that involves all possible identifier variables, which are not available to investigators.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Box S1. Definition of exclusion criteria. Box S2. Definition of exposure group with previous cardiovascular disease. Box S3. Definition of cases of overall dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia. Box S4. Definition of baseline covariates. Box S5. Validation of the imputation process. Table S1. Description of missing,complete case and imputed datasets. Table S2. Description of the baseline characteristics of the study population by sex. Table S3. Crude incidences (95% CI) of Alzheimer’s disease by sex, age and exposure groups. Table S4. Crude incidences (95% CI) of vascular dementia by sex, age and exposure groups. Table S5. Subdistribution hazard ratios (95% CI) of the exposure groups obtained in the Fine-Gray models. Figure S1. Flowchart of the study population. Figure S2. Unadjusted Cox model b-splines of hazard ratios of dementia types (panel A: all-cause dementia; B: Alzheimer’s disease; C: vascular dementia) according to exposure groups by sex and age. Figure S3. Complete case analysis to replicate the Cox model b-splines of hazard ratios of dementia types (panel A: all-cause dementia; B: Alzheimer’s disease; C: vascular dementia) according to exposure groups by sex and age. Figure S4. Cox model b-splines of hazard ratios of dementia types (panel A: all-cause dementia; B: Alzheimer’s disease; C: vascular dementia) according to exposure groups by sex and age. Censuring was applied at the first cardiovascular event or dementia onset during follow-up.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ponjoan, A., Blanch, J., Fages-Masmiquel, E. et al. Sex matters in the association between cardiovascular health and incident dementia: evidence from real world data. Alz Res Therapy 16, 58 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-024-01406-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-024-01406-x