Abstract

Background

Synapse damage and loss are fundamental to the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and lead to reduced cognitive function. The goal of this review is to address the challenges of forging new clinical development approaches for AD therapeutics that can demonstrate reduction of synapse damage or loss.

The key points of this review include the following:

-

Synapse loss is a downstream effect of amyloidosis, tauopathy, inflammation, and other mechanisms occurring in AD.

-

Synapse loss correlates most strongly with cognitive decline in AD because synaptic function underlies cognitive performance.

-

Compounds that halt or reduce synapse damage or loss have a strong rationale as treatments of AD.

-

Biomarkers that measure synapse degeneration or loss in patients will facilitate clinical development of such drugs.

-

The ability of methods to sensitively measure synapse density in the brain of a living patient through synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, concentrations of synaptic proteins (e.g., neurogranin or synaptotagmin) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or functional imaging techniques such as quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) provides a compelling case to use these types of measurements as biomarkers that quantify synapse damage or loss in clinical trials in AD.

Conclusion

A number of emerging biomarkers are able to measure synapse injury and loss in the brain and may correlate with cognitive function in AD. These biomarkers hold promise both for use in diagnostics and in the measurement of therapeutic successes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias afflict nearly 44 million people worldwide [1]. In the USA, nearly 6 million people have AD, a number that is expected to double by 2050 [2]. Only symptomatic treatments are currently available, and disease modeling techniques suggest that the beneficial effects of current treatments may peak by 6 months [3, 4]. More effective symptomatic treatments or first-of-a-kind disease-modifying therapies for AD continue to be a huge unmet medical need; these treatments would significantly impact the quality of life annual healthcare expenditure for AD patients, which were estimated to be $277B annually in 2018 and up to $1100B annually by 2050 [2].

Hypotheses regarding etiology of AD and potential targets for pharmacologic intervention have evolved over the recent decades of intense industry and academic research. Neurotransmitter hypotheses, while giving rise to the first drugs approved for treating AD, generated means for symptomatic relief but failed to generate disease-altering treatments [5]. Amyloid plaque- and tau tangle-related hypotheses, focused on aggregated Aβ peptide and tau protein, appeared to offer promising targets for disease-altering therapies, but most clinical programs targeting Aβ generation with small molecules and Aβ clearance with antibodies have been disappointing [6, 7]. Treatment with several anti-Aβ antibodies (solanezumab, with a high affinity for monomeric Aβ, and aducanumab and BAN2401, which target fibrillar Aβ) was associated with a small slowing of cognitive decline in subsets of patients with AD, but those targeting fibrils are associated with vasogenic edema and cerebral microhemorrhages, possibly limiting their clinical usefulness [7]. Understanding the role of soluble Aβ aggregates has led to the new hypotheses that these Aβ oligomers may be responsible for the neurotoxic etiology of AD, with hopes that therapeutics that reduce their synaptotoxicity may delay or stop the progression of AD [8]. Monitoring treatment-related reduction of such toxicity may provide suitable biomarker endpoints for drug efficacy and is independent of etiology of disease.

A foundational principle of neuroscience is that synaptic function underlies cognition. There is widespread acceptance of the premise that synapse damage or loss is the objective sign of neurodegeneration that is most highly correlated with cognitive decline in AD; this is supported by clinical, post-mortem, and non-clinical evidence as summarized below. Objective measures of synaptic damage or loss are therefore a special category of biomarkers expected to be most closely correlated with cognitive function.

The goal of this paper is to review the concept of biomarkers of synapse damage as a potential approvable endpoint for treatment in AD and other neurological indications and to review the literature in order to assist biopharmaceutical drug developers and regulators in addressing the challenges of forging new pathways for the approval of synaptoprotective AD therapeutics. The first portion of this manuscript will review the critical role played by synaptic damage in the pathophysiologic processes that underlie AD and their relation to cognitive decline. The second portion will review currently available biomarkers that measure synapse damage or loss in living patients, with a view towards their use as surrogate endpoints in clinical trials in AD.

The roles of synaptic damage and loss in cognition

The idea that changes in synapses mediate information storage dates back to Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s anatomical observations of brain structure in the late 1890s [9]. This gained popularity in the mid-twentieth century with Hebb’s postulate that synapses between neurons will be strengthened if they are active at the same time, and that this process contributes to learning [10]. This was supported experimentally by Kandel’s studies in Aplysia [11]. This concept was underscored by the discoveries of synaptic long-term potentiation by Bliss and Lomo [12] and the hippocampal synaptic plasticity in memory formation by Morris and colleagues [13]. In recognition of the importance of synaptic function to cognition, awards including the Brain Prize and the Nobel Prize have been awarded to multiple scientists for their work in this field.

Synapse dysfunction and loss correlates most strongly with the pathological cognitive decline experienced in Alzheimer’s disease [14,15,16,17,18,19]. This association was initially described through two independent methods, the estimation of synapse number using electron microscopy techniques [16] and measurements of synaptic protein concentrations [19], each of which showed a strong correlation between synapse number (or synaptic proteins) and cognitive scores on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE). This concept has been robustly replicated using a variety of approaches [14, 18, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26], including disease models. While the molecular cascades leading to synapse degeneration in AD have yet to be fully determined, there is ample evidence from both human brain and disease models supporting synaptotoxic roles of soluble pathological forms of Aβ and tau, as well as glial-mediated neuroinflammation (see [14] for an excellent recent meta-analysis). This paper will review evidence of these mechanisms, as well as approaches for their detection in patients.

Mechanisms of synapse damage and loss in AD

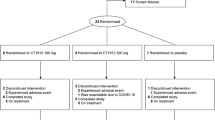

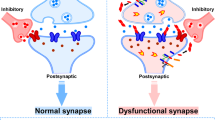

Amyloid plaques formed of aggregated Aβ peptide are one of the defining pathological lesions of AD [27,28,29]. In both human brain and mouse models expressing familial AD-associated amyloid precursor protein and presenilin mutations, plaques are associated with local synapse loss [Fig. 1, [30,31,32,33,34]] as well as memory and synaptic plasticity deficits [35,36,37]. However, total plaque load is not the factor most strongly correlated with cognitive decline [38] or synaptic pathology [17, 39] in AD. Instead, abundant data demonstrate that soluble forms of Aβ, rather than the large insoluble fibrils in plaques, are toxic to synapses [15, 40]. Lambert and colleagues found that fibril-free synthetic forms of Aβ oligomers (AβO) inhibited long-term potentiation (LTP) ex vivo [41], and in 2002, Walsh and colleagues demonstrated that naturally secreted AβO disrupt LTP in vivo [42]. Since then, many studies have shown that AβO may drive the cognitive impairment found in animal models of AD [43,44,45] and potentially also in human AD [46,47,48].

Exposure to oligomers in vitro produces rapid reduction in the expression of many synaptic proteins required for normal neurotransmission and for learning and memory formation within hours [49]; longer exposure produces frank loss of synapses and spines [45, 49,50,51]. Higher, non-physiological concentrations result in rapid neuronal cell death.

The presence of AβO has been correlated with synaptic plasticity impairment and frank synapse loss in mice and cell models [45, 49,50,51] and in human brains in AD [30, 52, 53]. Furthermore, AβO have been visualized within individual synapses of both mouse models and AD cases using high-resolution imaging techniques [30, 31, 54], arguing strongly that they may directly contribute to synaptic and cognitive dysfunction.

While Aβ monomers may interact with many receptors, in model systems, AβO have been demonstrated to bind to synaptic receptors including cellular prion protein, NgR1, EphB2, and PirB/LilrB2; additional receptor proteins have yet to be rigorously defined [55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. One important regulator of the oligomer receptor complex is the sigma-2 protein receptor complex [62, 63], the target of the AD disease-modifying drug candidate CT1812 [64]. Downstream of interacting with synaptic receptors, robust evidence suggests AβO cause calcium influx and downstream synaptic dysfunction [15, 65, 66].

Another defining neuropathological lesion of AD is the aggregation of truncated, misfolded, and hyperphosphorylated tau into neurofibrillary tangles [27]. Tau pathology correlates with neuron loss and cognitive decline in AD [28, 67]. In accordance with the observation that tau causes neuron death, mouse models that express tau mutations that cause frontotemporal dementias with tau pathology demonstrate neuron loss [68,69,70,71], early synapse loss, and disruption of neuronal network function [72,73,74,75,76,77]. As has been observed with Aβ, the forms of tau that may be toxic are the soluble, non-fibrillar, and highly reactive forms, the oligomers [78,79,80].

Loss of physiological tau function may contribute to synapse degeneration by impairing axonal transport of cargoes needed at synapses, including mitochondria [81, 82]. Part of the synaptic and network dysfunction in tauopathy mice and in AD is likely due to direct effects of tau at synapses. Along with the canonical microtubule stabilizing role of tau, this versatile protein has also been shown to play a physiological role in dendrites including post-synaptic densities and in pre-synaptic terminals [83,84,85]. In human AD brain, small aggregates of phospho-tau are observed in both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic regions, and several groups have observed phospho-tau in biochemically isolated synaptic fractions [85,86,87]. Importantly, accumulation of phospho-tau in synaptic fractions was much higher in people with AD (cases) than in people with high pathological burdens who did not exhibit dementia symptoms [48]. Together, these data strongly indicate that pathological forms of tau at synapses contribute to synaptic dysfunction.

Based on the genetic causes of rare forms of familial AD, which all act to increase Aβ accumulation, and the timing of pathological development where plaque pathology is an early pathological feature preceding appreciable tau pathology by many years, it is widely thought that Aβ is “upstream” of tau in initiating AD pathogenesis [88]. One of the key challenges in this field is understanding the links between Aβ and tau, and recent data indicate that these proteins may cooperate to cause synaptic degeneration. Several pathways involving tau have been implicated in AβO-mediated synapse loss. AβO activation of the NMDA receptor has been reported to cause excitotoxicity through the recruitment of Fyn kinase by tau to the post-synaptic density in mice [83, 89, 90]. Lowering tau levels also protects against some of the synaptic effects of AβO [91, 92].

Beyond the direct effects of these pathological proteins on neurons and synapses, epidemiologic and genetic data strongly implicate inflammatory mechanisms in synapse damage in AD. In particular, recent data indicate that microglia may play an active role in synapse loss [93]. The most important genetic risk factor for late-onset AD is inheritance of the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 (APOE ε4) allele [94]. The ApoE4 isoform is highly expressed in astrocytes under physiological conditions, but its expression is upregulated in microglia in mouse models of AD [95]. The effects of AβO at synapses are exacerbated by ApoE4 in plaque-bearing mouse models and human AD brain and are ameliorated by removing endogenous ApoE [30, 96, 97]. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), complement receptor 1 (CR1), and CD33 are all expressed in microglia, where they may affect phagocytosis of synapses [93]. The complement system has emerged recently as particularly interesting in AD because the tagging of synapses with C1q downstream of both Aβ and tau pathology causes CR3-mediated microglial phagocytosis of synapses [98,99,100,101,102]. While several members of the complement pathway have been observed to be upregulated in AD brain and to correlate with tau pathology [101, 102], it remains unknown whether microglial phagocytosis of synapses in human disease actively drives synapse loss or simply removes synapses after damage has occurred.

Importantly, in mouse models of AD, the effects on synapses of key elements of AD pathogenesis—AβO, tau, or inflammation—are reversible. In multiple studies, deficits in LTP, memory impairment, and synapse loss recover in mice when levels of AβO, tau, or inflammation are lowered [69, 103,104,105,106,107,108]. This plasticity of synaptic connections and their potential for recovery lends hope for therapeutics that reduce synaptotoxicity in AD. Regardless of the causative role of AβO and the contributions to disease progression of tau, p-tau, glia, and inflammation processes, synapse dysfunction has a number of downstream neurophysiological consequences including altered neuronal oscillatory behavior and an imbalance between excitation and inhibition. These alter neural circuit function and adversely impact behavior. As such, normal synapse number and function is the basis for cognitive performance and is an ideal measure of brain damage due to disease.

Biomarkers of synapse damage or loss

The importance of synapses in cognition and the strong links among synapses, AD pathophysiology, and the symptoms observed in AD make a compelling case for the use of biomarkers of synapse damage or loss as proxies for synaptic and cognitive function in AD. A recent publication of the NIA-AA Research Framework emphasized the necessity of a biological definition of the disease for clinical progress and established the A/T/N biomarker classification system, where “A” stands for amyloid beta, “T” for tau, and “N” for neurodegeneration [109], a broad concept that includes destruction of system-level circuits and regional volume loss, as well as injury to individual cellular elements such as axons, dendrites, and synapses. The extent to which this A/T/N biomarker classification system is confined to studies of the pathobiology of AD, versus used to define patient populations that are enrolled into clinical trials, will be subject of valuable scientific discussion [110]. In the remainder of this paper, we will focus on “N” type biomarkers specifically related to synapse damage or loss.

Visualization of synapses in the living brain has recently been described through the labelling of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) with the [11C]UCB-J positron emission tomography (PET) ligand [111,112,113]. (Additional SV2A radioligands, [11C]UCB-A and [18F]UCB-H, have also been under development.) Comparing a group of AD cases with cognitively healthy aged cases, a reduction of approximately 40% of SV2A signal was observed in the hippocampus in AD cases [114]. The use of this PET ligand to measure synapse loss longitudinally in AD is not yet well established. However, as a direct measure of synapse density, this biomarker in combination with other cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers and functional imaging approaches, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), quantitative electroencephalogram (qEEG), or fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET), is independent of the disease hypothesis and has the potential to be a strong indicator of brain degeneration and cognitive status (Fig. 2). Recent innovations such as this ability to sensitively measure synapse density in the brain of a living patient via SV2A PET imaging, low concentrations of synaptic protein proteolytic fragments in the CSF via sensitive ELISAs or LC/MSMS methods, changes in cortical synaptic currents measured by qEEG, or disruption of glucose metabolism measured by FDG-PET promise to revolutionize the ability to stage patients and to define disease more precisely. Furthermore, as synapses are a fundamental brain structure responsible for cognitive output, measures of synapse density have the most value in their ability to assess responses to disease-modifying treatments.

Following the identification of synaptic protein fragments of neurogranin, SNAP-25, and synaptotagmin in CSF [115, 116], specific protein biomarkers of synapse degeneration have begun to emerge in recent years. Protein fragments of neurogranin, a dendritic protein involved in LTP, are increased in CSF of patients with AD, and full-length neurogranin is decreased in post-mortem brain tissues [117, 118]. Furthermore, encouraging data show that increased neurogranin fragments in CSF correlate with future cognitive decline, brain atrophy, and glucose metabolism, even at early stages of the disease [117, 119,120,121], and that the increase in CSF neurogranin seems to be specific for AD [122, 123]. This use of CSF measurement of neurogranin concentration underlies the concept that an accurate biomarker of synapse loss reflects cognitive function based on the correlation between cognitive function and synaptic proteins in the post-mortem brain.

Other synaptic proteins including SNAP25, RAB3A, GAP43, AMPA receptor subunits, and a number of other proteins also show promise as CSF biomarkers of synaptic damage and loss [24, 25, 124, 125]. In addition, recent research proposes inflammatory markers, detectable in the CSF, as possible biomarkers of neurodegeneration in AD, though their correlation to synapse loss in particular remains unclear [126]. Biomarkers of glial activation such as CSF TREM2, chitotriosidase, CCL2, and YLK-40 have been observed in AD CSF [127,128,129,130]. Eventually, a panel of synaptic protein biomarkers may be a reliable readout for the different aspects of synapse loss (pre-synaptic, synaptic vesicle, and dendritic) and a predictor of memory decline. Indeed, a recent study found that a group of synaptic proteins changes in CSF before markers of neurodegeneration are observed in AD [131]. Although CSF collection is more invasive than blood sampling, robust blood-based biomarkers of synaptic damage are not yet available. It is, for example, possible to measure neurogranin concentration in plasma, but there is no plasma-CSF correlation [119, 132]. It may be possible to develop higher sensitivity assays and analyses of neuron-derived exosomes in blood with advancing technologies [130, 133].

Finally, functional imaging approaches are additional tools for visualizing the health and function of neurons affected by AD. EEG represents a dynamic measurement of synaptic function in cortical pyramidal neuronal dendrites that can capture the summed excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic potentials at a macroscopic spatial scale with millisecond time resolution [134,135,136,137]. Overall, quantitative EEG analysis provides the most direct and dynamic clinical representation of neuronal and synaptic function in AD patients; however, while it is sensitive to changes in neuronal circuit responses resulting from synaptic dysfunction, it cannot discriminate between the exact mechanisms of action underlying synaptic dys/function. Alterations in quantitative measures derived from EEG data in patients with AD have been widely described and have been shown to be sensitive to disease progression [134, 138, 139] and to correlate with CSF biomarkers of AD [140]. Furthermore, EEG is non-invasive, robust, efficacious, and widely available in hospitals. Although EEG itself is an “old” technique, quantitative instead of visual analysis of EEG signals provides a wealth of information and is a novel and rapidly developing method in modern neuroscience. Spectral power measures (i.e., the percentage of the total brain activity accounted for by a specific wave frequency) in task-free EEGs can be calculated and reflect the oscillatory activity of the underlying brain network responsible for cognitive functioning. In patients with AD, the EEG shows distinct changes in spectral power indicating a gradual, diffuse slowing of brain electrical activity with progression of the disease [138]. In particular, the gradual relative increase of neuronal theta (4–8 Hz) activity appears to be a robust sign in early AD. It has been recently demonstrated that theta band activity is a marker of future cognitive decline in non-demented amyloid-positive subjects with additive value above other markers of disease progression such as medial temporal atrophy on MRI [141] and importantly that its increase can be reversed in response to approved AD therapeutics [142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151].

In addition to EEG, the use of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET), which enables the visualization of glucose metabolism rates in the brain, has been investigated for its use in AD. In neurons, the demand for glucose is driven partly by synaptic terminals, which generate ATP needed for synthesis, release, and recycling of neurotransmitter molecules, for the maintenance of the normal resting potential and for the recovery from action potentials. The cerebral metabolic rate of glucose as measured with FDG-PET provides a direct index of synaptic functioning and an indirect measure of synaptic density [152]. Therefore, a disruption in glucose metabolism may be a very direct determinant of synaptic dysfunction [reviewed in [153]]. The ability to detect changes in glucose metabolism prior to the onset of clinical symptoms of AD may aid earlier diagnosis of AD [153]. Data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) have confirmed longitudinal associations between FDG-PET and clinical measures [154] and have suggested that FDG-PET may help to increase the statistical power of diagnosis over conventional cognitive measures, aid subject selection, and substantially reduce the sample size required for clinical trials [155, 156], though these findings must be confirmed in broader sample sizes and longer studies, and require further clarification regarding their applicability to AD or other types of dementias. Therapeutic trials have provided strong support for the use of FDG-PET as a clinically relevant primary biomarker outcome in proof of concept studies that has the power to detect active-placebo differences less than half as great as the best clinical measures [157]. However, additional studies showing a relationship between an effective treatment’s FDG-PET and clinical findings are needed to provide further support for its “theragnostic” value.

A key further issue for future exploration is the longitudinal relationship between biomarkers and cognitive outcome measures. Even modest correlations between the two would yield helpful evidence of clinical relevance. Recent studies have observed modest correlations between the International Shopping List Test, a measure of episodic memory, with various volumetric MRI measures and especially hippocampal volume [158]. Change over time correlations would provide further helpful support. Furthermore, as understanding of these biomarkers improves, their use may help in discerning AD from other types of dementias, in particular through localization of compromised synapses to the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and other brain regions. Finally, opportunities for biomarker validation are offered by the extension of assessment to domains of cognition known to be compromised early in the disease process. Recent FDA draft guidance has called for trials to feature the use of “sensitive neuropsychological measures.” Commentators on the draft guidance have highlighted the need for trials to include measures of spatial memory skills, working memory, attention, and executive function [159].

Conclusions

Synapses are essential parts of neurons that form the requisite connections of the neuronal networks that underlie cognition. The cognitive impairment in AD closely parallels the loss of synapses due to the toxic effects of Aβ, tau, and inflammation. Emerging biomarkers of synapse damage reflect such synapse injury and loss in the brain due to disease. Hence, biomarkers of synapse damage and loss, especially the use of multiple categories of biomarkers in combination with one another, hold great promise as biological measures that should correlate with cognitive function in AD.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- APOE ε4:

-

Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4

- AβO:

-

Aβ oligomers

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- FDA:

-

US Food and Drug Administration

- FDG-PET:

-

Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET

- LTP:

-

Long-term potentiation

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental Status Examination

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- qEEG:

-

Quantitative electroencephalography

- SV2A PET:

-

Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A positron emission tomography

References

Nichols E, Szoeke CEI, Vollset SE, Abbasi N, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(1):88–106.

Association A. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. Elsevier; 2018; 14(3):367–429 [cited 2018 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1552526018300414.

Persson CM, Wallin AK, Levander S, Minthon L. Changes in cognitive domains during three years in patients with Alzheimer’s disease treated with donepezil. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19208247.

Ito K, Ahadieh S, Corrigan B, French J, Fullerton T, Tensfeldt T, et al. Disease progression meta-analysis model in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(1):39–53 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19592311.

Kandimalla R, Reddy PH. Therapeutics of neurotransmitters in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(4):1049–69 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28211810.

Knopman DS. Lowering of amyloid-beta by β-secretase inhibitors - some informative failures. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(15):1476–8 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30970194.

van Dyck CH. Anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease: pitfalls and promise. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83(4):311–9 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.010.

Viola KL, Klein WL. Amyloid beta oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, treatment, and diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:183–206.

y Cajal SR. Histology of the nervous system of man and vertebrates, volume 1. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Hebb D. The organization of behavior: a neuropsychological theory [Internet]. New York: Wiley; 1949. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/sce.37303405110.

Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science. 2001;294(5544):1030–8 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11691980.

Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973;232(2):331–56 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4727084.

Takeuchi T, Duszkiewicz AJ, RGM M. The synaptic plasticity and memory hypothesis: encoding, storage and persistence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1633):20130288 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24298167.

De Wilde MC, Overk CR, Sijben JW, Masliah E. Meta-analysis of synaptic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease reveals selective molecular vesicular machinery vulnerability. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016;12(6):633–44. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.005.

Spires-Jones TL, Hyman B. The intersection of amyloid beta and tau at synapses in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2014;82(4):756–71. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.004.

DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(5):457–64 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2360787.

Blennow K, Bogdanovic N, Alafuzoff I, Ekman R, Davidsson P. Synaptic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to severity of dementia, but not to senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, or the ApoE4 allele. J Neural Transm. 1996;103(5):603–18 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8811505.

DeKosky ST, Scheff SW, Styren SD. Structural correlates of cognition in dementia: quantification and assessment of synapse change. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5(4):417–21 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9117556.

Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(4):572–80 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1789684.

Scheff SW, Price DA. Synaptic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of ultrastructural studies. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(8):1029–46 [cited 2014 May 13]. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0197458003001805.

Scheff SW, Price DA, Ansari MA, Roberts KN, Schmitt FA, Ikonomovic MD, et al. Synaptic change in the posterior cingulate gyrus in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(3):1073–90 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24529280.

Scheff SW, Price DA, Schmitt FA, Roberts KN, Ikonomovic MD, Mufson EJ. Synapse stability in the precuneus early in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35(3):599–609 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23478309.

Kashani A, Lepicard E, Poirel O, Videau C, David JP, Fallet-Bianco C, et al. Loss of VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 in the prefrontal cortex is correlated with cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29(11):1619–30 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17531353.

Bereczki E, Branca RM, Francis PT, Pereira JB, Baek J-H, Hortobágyi T, et al. Synaptic markers of cognitive decline in neurodegenerative diseases: a proteomic approach. Brain. 2018;141(2):582–95 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29324989.

Bereczki E, Francis PT, Howlett D, Pereira JB, Höglund K, Bogstedt A, et al. Synaptic proteins predict cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(11):1149–58 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27224930.

Whitfield DR, Vallortigara J, Alghamdi A, Howlett D, Hortobágyi T, Johnson M, et al. Assessment of ZnT3 and PSD95 protein levels in Lewy body dementias and Alzheimer’s disease: association with cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(12):2836–44 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25104558.

Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MMB, de Strooper B, Frisoni GB, Salloway S, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):505–17 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26921134.

Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1(1):a006189 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22229116.

Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1–13 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22265587.

Koffie RM, Hashimoto T, Tai H-C, Kay KR, Serrano-Pozo A, Joyner D, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 effects in Alzheimer’s disease are mediated by synaptotoxic oligomeric amyloid-β. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 7):2155–68 [cited 2014 May 1]. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3381721&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Koffie RM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Hashimoto T, Adams KW, Mielke ML, Garcia-Alloza M, et al. Oligomeric amyloid beta associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(10):4012–7 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2656196&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Spires TL, Meyer-Luehmann M, Stern EA, McLean PJ, Skoch J, Nguyen PT, et al. Dendritic spine abnormalities in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice demonstrated by gene transfer and intravital multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci. 2005;25(31):7278–87 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16079410.

Jackson RJ, Rudinskiy N, Herrmann AG, Croft S, Kim JM, Petrova V, et al. Human tau increases amyloid β plaque size but not amyloid β-mediated synapse loss in a novel mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2016;44:3056–66 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27748574.

Yu Y, Jans DC, Winblad B, Tjernberg LO, Schedin-Weiss S. Neuronal Aβ42 is enriched in small vesicles at the presynaptic side of synapses. Life Sci Alliance. 2018;1(3):e201800028 Available from: http://www.life-science-alliance.org/lookup/doi/10.26508/lsa.201800028.

Ashe KH, Zahs KR. Probing the biology of Alzheimer’s disease in mice. Neuron. 2010;66(5):631–45 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20547123.

Sasaguri H, Nilsson P, Hashimoto S, Nagata K, Saito T, De Strooper B, et al. APP mouse models for Alzheimer’s disease preclinical studies. EMBO J. 2017;36(17):2473–87 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28768718.

Saito T, Matsuba Y, Mihira N, Takano J, Nilsson P, Itohara S, et al. Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(5):661–3 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24728269.

Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(5):362–81 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22487856.

Masliah E, Hansen L, Albright T, Mallory M, Terry RD. Immunoelectron microscopic study of synaptic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;81(4):428–33 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1903014.

Cline EN, Bicca MA, Viola KL, Klein WL. The amyloid-β oligomer hypothesis: beginning of the third decade. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:S567–610. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29843241.

Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(11):6448–53 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=27787&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416(6880):535–9 [cited 2018 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/416535a.

Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(1):79–84 [cited 2014 May 2]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15608634.

Lesné S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, et al. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440(7082):352–7 [cited 2014 Apr 29]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16541076.

Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):837–42 [cited 2014 May 21]. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2772133&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Lesné SE, Sherman MA, Grant M, Kuskowski M, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, et al. Brain amyloid-β oligomers in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 5):1383–98 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23576130.

Esparza TJ, Zhao H, Cirrito JR, Cairns NJ, Bateman RJ, Holtzman DM, et al. Amyloid-β oligomerization in Alzheimer dementia versus high-pathology controls. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(1):104–19 [cited 2014 Apr 28]. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3563737&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Perez-Nievas BG, Stein TD, Tai H-C, Dols-Icardo O, Scotton TC, Barroeta-Espar I, et al. Dissecting phenotypic traits linked to human resilience to Alzheimer’s pathology. Brain. 2013;136(8):2510–26 Available from: https://academic.oup.com/brain/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/brain/awt171.

Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, Clemente AS, Velasco PT, Wood M, et al. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27(4):796–807 [cited 2014 May 2]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17251419.

Wang Z, Jackson RJ, Hong W, Taylor WM, Corbett GT, Moreno A, et al. Human brain-derived Aβ oligomers bind to synapses and disrupt synaptic activity in a manner that requires APP. J Neurosci. 2017;37(49):11947–66 Available from: http://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/05/09/135673.

Calabrese B, Shaked GM, Tabarean IV, Braga J, Koo EH, Halpain S. Rapid, concurrent alterations in pre- and postsynaptic structure induced by naturally-secreted amyloid-beta protein. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35(2):183–93 [cited 2014 Apr 29]. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2268524&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Lue L-F, Kuo Y-M, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, et al. Soluble amyloid β peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(3):853–62 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S000294401065184X.

Bao F, Wicklund L, Lacor PN, Klein WL, Nordberg A, Marutle A. Different β-amyloid oligomer assemblies in Alzheimer brains correlate with age of disease onset and impaired cholinergic activity. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(4):825.e1–13 [cited 2014 May 15]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.05.003.

Pickett EK, Koffie RM, Wegmann S, Henstridge CM, Herrmann AG, Colom-Cadena M, et al. Non-fibrillar oligomeric amyloid-β within synapses. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53(3):787–800.

Benilova I, De Strooper B. Neuroscience. Promiscuous Alzheimer’s amyloid: yet another partner. Science. 2013;341(6152):1354–5 [cited 2014 mMay 21]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24052299.

Haas LT, Salazar SV, Kostylev MA, Um JW, Kaufman AC, Strittmatter SM. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 couples cellular prion protein to intracellular signalling in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 2):526–46 [cited 2018 Oct 18]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/brain/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/brain/awv356.

Alon A, Schmidt HR, Wood MD, Sahn JJ, Martin SF, Kruse AC. Identification of the gene that codes for the σ 2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(27):7160–5 Available from: http://www.pnas.org/lookup/doi/10.1073/pnas.1705154114.

Xu J, Zeng C, Chu W, Pan F, Rothfuss JM, Zhang F, et al. Identification of the PGRMC1 protein complex as the putative sigma-2 receptor binding site. Nat Commun. 2011;2(2):380 [cited 2014 May 12]. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3624020&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Riad A, Zeng C, Weng C-C, Winters H, Xu K, Makvandi M, et al. Sigma-2 receptor/TMEM97 and PGRMC-1 increase the rate of internalization of LDL by LDL receptor through the formation of a ternary complex. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16845 Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-35430-3.

Smith LM, Strittmatter SM. Binding sites for amyloid-β oligomers and synaptic toxicity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7(5):a024075 Available from: http://perspectivesinmedicine.cshlp.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/cshperspect.a024075.

Cissé M, Halabisky B, Harris J, Devidze N, Dubal DB, Sun B, et al. Reversing EphB2 depletion rescues cognitive functions in Alzheimer model. Nature. 2011;469(7328):47–52 [cited 2014 May 1]. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3030448&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Izzo NJ, Staniszewski A, To L, Fa M, Teich AF, Saeed F, et al. Alzheimer’s therapeutics targeting amyloid beta 1-42 oligomers I: Abeta 42 oligomer binding to specific neuronal receptors is displaced by drug candidates that improve cognitive deficits. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111898 Public Library of Science; [cited 2014 Nov 17]. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111898.

Izzo NJ, Xu J, Zeng C, Kirk MJ, Mozzoni K, Silky C, et al. Alzheimer’s therapeutics targeting amyloid beta 1-42 oligomers II: Sigma-2/PGRMC1 receptors mediate Abeta 42 oligomer binding and synaptotoxicity. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111899 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25390692.

Grundman M, Morgan R, Lickliter JD, Schneider LS, DeKosky S, Izzo NJ, et al. A phase 1 clinical trial of the sigma-2 receptor complex allosteric antagonist CT1812, a novel therapeutic candidate for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement (New York, N Y). 2019;5:20–6 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2018.11.001.

Kuchibhotla KV, Lattarulo CR, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Synchronous hyperactivity and intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes in Alzheimer mice. Science. 2009;323(5918):1211–5 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19251629.

Busche MA, Eichhoff G, Adelsberger H, Abramowski D, Wiederhold K-H, Haass C, et al. Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2008;321(5896):1686–9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18802001.

Gomez-Isla T. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(1):17–24.

Spires TL, Orne JD, SantaCruz K, Pitstick R, Carlson GA, Ashe KH, et al. Region-specific dissociation of neuronal loss and neurofibrillary pathology in a mouse model of tauopathy. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(5):1598–607.

Santa Cruz K. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309(5733):476–81 Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi/10.1126/science.1113694.

Polydoro M, Acker CM, Duff K, Castillo PE, Davies P. Age-dependent impairment of cognitive and synaptic function in the htau mouse model of tau pathology. J Neurosci. 2009;29(34):10741–9 Available from: http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/doi/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1065-09.2009.

Allen B, Ingram E, Takao M, Smith MJ, Jakes R, Virdee K, et al. Abundant tau filaments and nonapoptotic neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing human P301S tau protein. J Neurosci. 2002;22(21):9340–51 Available from: isi:000175724500174.

Busche MA. In vivo two-photon calcium imaging of hippocampal neurons in Alzheimer mouse models. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1750:341–51 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29512084.

Fu H, Possenti A, Freer R, Nakano Y, Villegas NCH, Tang M, et al. A tau homeostasis signature is linked with the cellular and regional vulnerability of excitatory neurons to tau pathology. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(1):47–56 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0298-7.

Menkes-Caspi N, Yamin HG, Kellner V, Spires-Jones TL, Cohen D, Stern EA. Pathological tau disrupts ongoing network activity. Neuron. 2015;85(5):959–66. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.01.025.

Crimins JL, Rocher AB, Peters A, Shultz P, Lewis J, Luebke JI. Homeostatic responses by surviving cortical pyramidal cells in neurodegenerative tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(5):551–64.

Rocher AB, Crimins JL, Amatrudo JM, Kinson MS, Todd-Brown MA, Lewis J, et al. Structural and functional changes in tau mutant mice neurons are not linked to the presence of NFTs. Exp Neurol [Internet]. 2010;223(2):385–93 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0014488609003100.

Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, Huang SM, Iwata N, Saido TCC, et al. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron. 2007;53(3):337–51.

Sealey MA, Vourkou E, Cowan CM, Bossing T, Quraishe S, Grammenoudi S, et al. Distinct phenotypes of three-repeat and four-repeat human tau in a transgenic model of tauopathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;105:74–83.

Ghag G, Bhatt N, Cantu DV, Guerrero-Munoz MJ, Ellsworth A, Sengupta U, et al. Soluble tau aggregates, not large fibrils, are the toxic species that display seeding and cross-seeding behavior. Protein Sci. 2018;27(11):1901–9.

Kopeikina KJ, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL. Soluble forms of tau are toxic in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Neurosci. 2012;3(3):223–33 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23029602.

Kopeikina KJ, Carlson GA, Pitstick R, Ludvigson AE, Peters A, Luebke JI, et al. Tau accumulation causes mitochondrial distribution deficits in neurons in a mouse model of tauopathy and in human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(4):2071–82. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.004.

Pickett EK, Rose J, McCrory C, McKenzie CA, King D, Smith C, et al. Region-specific depletion of synaptic mitochondria in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(5):747–57 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1903-2.

Ittner A, Ittner LM. Dendritic tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2018;99(1):13–27 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.003.

McInnes J, Wierda K, Snellinx A, Bounti L, Wang YC, Stancu IC, et al. Synaptogyrin-3 mediates presynaptic dysfunction induced by tau. Neuron. 2018;97(4):823–835.e8.

Zhou L, McInnes J, Wierda K, Holt M, Herrmann AG, Jackson RJ, et al. Tau association with synaptic vesicles causes presynaptic dysfunction. Nat Commun. 2017;8(May):15295 Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/ncomms15295.

Tai H, Serrano-Pozo A, Hashimoto T, Frosch MP, Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT. The synaptic accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau oligomers in Alzheimer disease is associated with dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(4):1426–35 [cited 2014 May 20]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.033.

Tai HC, Wang BY, Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT. Frequent and symmetric deposition of misfolded tau oligomers within presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2(1):1–14.

Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(6):595–608. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27025652.

Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142(3):387–97.

Roberson ED, Halabisky B, Yoo JW, Yao J, Chin J, Yan F, et al. Amyloid-/Fyn-induced synaptic, network, and cognitive impairments depend on tau levels in multiple mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):700–11 Available from: http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/doi/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4152-10.2011.

Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid -induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316(5825):750–4 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17478722.

Shipton OA, Leitz JR, Dworzak J, Acton CEJ, Tunbridge EM, Denk F, et al. Tau protein is required for amyloid {beta}-induced impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2011;31(5):1688–92 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21289177.

Henstridge CM, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL. Beyond the neuron–cellular interactions early in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20(2):1 Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41583-018-0113-1.

Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261(5123):921–3 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8346443.

Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2017;169(7):1276–1290.e17 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28602351.

Hudry E, Dashkoff J, Roe AD, Takeda S, Koffie RM, Hashimoto T, et al. Gene transfer of human Apoe isoforms results in differential modulation of amyloid deposition and neurotoxicity in mouse brain. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(212):212ra161 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24259049.

Hudry E, Klickstein J, Cannavo C, Jackson R, Muzikansky A, Gandhi S, et al. Opposing roles of apolipoprotein E in aging and neurodegeneration. Life Sci Alliance. 2019;2(1):e201900325 Available from: http://www.life-science-alliance.org/lookup/doi/10.26508/lsa.201900325.

Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, et al. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science. 2016;8373(6286):1–9 Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi/10.1126/science.aad8373.

Shi Q, Chowdhury S, Ma R, Le KX, Hong S, Caldarone BJ, et al. Complement C3 deficiency protects against neurodegeneration in aged plaque-rich APP/PS1 mice. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(392):eaaf6295. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28566429.

Davies C, Spires-Jones TL. Complementing tau: new data show that the complement system is involved in degeneration in tauopathies. Neuron. 2018;100(6):1267–9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30571935.

Litvinchuk A, Wan Y-W, Swartzlander DB, Chen F, Cole A, Propson NE, et al. Complement C3aR inactivation attenuates tau pathology and reverses an immune network deregulated in tauopathy models and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2018;100(6):1337–1353.e5 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30415998.

Dejanovic B, Huntley MA, De Mazière A, Meilandt WJ, Wu T, Srinivasan K, et al. Changes in the synaptic proteome in tauopathy and rescue of tau-induced synapse loss by C1q antibodies. Neuron. 2018;100(6):1322–1336.e7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30392797.

Spires-Jones TL, Mielke ML, Rozkalne A, Meyer-Luehmann M, de Calignon A, Bacskai BJ, et al. Passive immunotherapy rapidly increases structural plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33(2):213–20 [cited 2014 May 21]. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2672591&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Sydow A, Van der Jeugd A, Zheng F, Ahmed T, Balschun D, Petrova O, et al. Reversibility of Tau-related cognitive defects in a regulatable FTD mouse model. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45(3):432–7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21822709.

Sydow A, Van der Jeugd A, Zheng F, Ahmed T, Balschun D, Petrova O, et al. Tau-induced defects in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory are reversible in transgenic mice after switching off the toxic Tau mutant. J Neurosci. 2011;31(7):2511–25 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21325519.

Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, Mathews PM, Jiang Y, Schmidt SD, et al. A beta peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):979–82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11140685.

Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400(6740):173–7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10408445.

Bittar A, Sengupta U, Kayed R. Prospects for strain-specific immunotherapy in Alzheimer’s disease and tauopathies. NPJ vaccines. 2018;3:9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29507776.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14(4):535–62 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

McCleery J, Flicker L, Richard E, Quinn TJ. When is Alzheimer’s not dementia-Cochrane commentary on The National Institute on Ageing and Alzheimer’s Association Research Framework for Alzheimer’s Disease. Age Ageing. 2019;48(2):174–7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30329009.

Finnema SJ, Nabulsi NB, Eid T, Detyniecki K, Lin S, Chen M, et al. Imaging synaptic density in the living human brain. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(348):348ra96 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27440727.

Constantinescu CC, Tresse C, Zheng M, Gouasmat A, Carroll VM, Mistico L, et al. Development and in vivo preclinical imaging of fluorine-18-labeled synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) PET tracers. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019;21(3):509–18 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11307-018-1260-5.

Li S, Cai Z, Wu X, Holden D, Pracitto R, Kapinos M, et al. Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of a novel PET radiotracer for imaging of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) in nonhuman primates. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10(3):1544–54 Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00526.

Chen M-K, Mecca AP, Naganawa M, Finnema SJ, Toyonaga T, Lin S, et al. Assessing synaptic density in Alzheimer disease with synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A positron emission tomographic imaging. JAMA Neurol. 2018;8042:1–10 Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/2687472?widget=personalizedcontent&previousarticle=2687466.

Davidsson P, Jahn R, Bergquist J, Ekman R, Blennow K. Synaptotagmin, a synaptic vesicle protein, is present in human cerebrospinal fluid: a new biochemical marker for synaptic pathology in Alzheimer disease? Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1996;27(2):195–210 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8962603.

Davidsson P, Puchades M, Blennow K. Identification of synaptic vesicle, pre- and postsynaptic proteins in human cerebrospinal fluid using liquid-phase isoelectric focusing. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(3):431–7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10217148.

Kvartsberg H, Lashley T, Murray CE, Brinkmalm G, Cullen NC, Höglund K, et al. The intact postsynaptic protein neurogranin is reduced in brain tissue from patients with familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137(1):89–102 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30244311.

Thorsell A, Bjerke M, Gobom J, Brunhage E, Vanmechelen E, Andreasen N, et al. Neurogranin in cerebrospinal fluid as a marker of synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2010;1362:13–22. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.073.

Kvartsberg H, Duits FH, Ingelsson M, Andreasen N, Öhrfelt A, Andersson K, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of the synaptic protein neurogranin correlates with cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(10):1180–90 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25533203.

Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Skillbäck T, Törnqvist U, Andreasson U, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin: relation to cognition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 11):3373–85 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26373605.

Tarawneh R, D’Angelo G, Crimmins D, Herries E, Griest T, Fagan AM, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of the synaptic marker neurogranin in Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(5):561–71 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27018940.

Portelius E, Olsson B, Höglund K, Cullen NC, Kvartsberg H, Andreasson U, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin concentration in neurodegeneration: relation to clinical phenotypes and neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(3):363–76 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29700597.

Wellington H, Paterson RW, Portelius E, Törnqvist U, Magdalinou N, Fox NC, et al. Increased CSF neurogranin concentration is specific to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2016;86(9):829–35.

Sandelius Å, Portelius E, Källén Å, Zetterberg H, Rot U, Olsson B, et al. Elevated CSF GAP-43 is Alzheimer’s disease specific and associated with tau and amyloid pathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(1):55–64 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30321501.

Brinkmalm A, Brinkmalm G, Honer WG, Frölich L, Hausner L, Minthon L, et al. SNAP-25 is a promising novel cerebrospinal fluid biomarker for synapse degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:53 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4253625&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Rauchmann B-S, Sadlon A, Perneczky R. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Soluble TREM2 and inflammatory proteins in Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31958095.

Suárez-Calvet M, Kleinberger G, Araque Caballero MÁ, Brendel M, Rominger A, Alcolea D, et al. sTREM2 cerebrospinal fluid levels are a potential biomarker for microglia activity in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and associate with neuronal injury markers. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(5):466–76 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26941262.

Piccio L, Deming Y, Del-Águila JL, Ghezzi L, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 is higher in Alzheimer disease and associated with mutation status. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):925–33 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26754641.

Heslegrave A, Heywood W, Paterson R, Magdalinou N, Svensson J, Johansson P, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 concentration in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:3 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26754172.

Lashley T, Schott JM, Weston P, Murray CE, Wellington H, Keshavan A, et al. Molecular biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and prospects. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11(5):dmm031781. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29739861.

Lleó A, Núñez-Llaves R, Alcolea D, Chiva C, Balateu-Paños D, Colom-Cadena M, et al. Changes in synaptic proteins precede neurodegeneration markers in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019;18(3):546–60 Available from: http://www.mcponline.org/lookup/doi/10.1074/mcp. RA118.001290.

Palmqvist S, Insel PS, Stomrud E, Janelidze S, Zetterberg H, Brix B, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarker trajectories with increasing amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2019;11(12):dmm031781. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.15252/emmm.201911170.

Winston CN, Goetzl EJ, Akers JC, Carter BS, Rockenstein EM, Galasko D, et al. Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia with neuronally derived blood exosome protein profile. Alzheimer’s Dement (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2016;3:63–72 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27408937.

Poil SS, de Haan W, van der Flier WM, Mansvelder HD, Scheltens P, Linkenkaer-Hansen K. Integrative EEG biomarkers predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease at the MCI stage. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5(OCT):1–12.

van der Zande JJ, Gouw AA, van Steenoven I, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, Lemstra AW. EEG characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer’s disease and mixed pathology. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10(JUL):1–10.

Schomer DL, da Silva FL. Niedermeyer’s electroencephalography. Basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins; 2010.

Ebersole JS, Pedley TA. Current practice of clinical electroencephalography, 3rd edn. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(5):604–5. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00643.x.

Jeong J. EEG dynamics in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115(7):1490–505 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15203050.

Smailovic U, Koenig T, Laukka EJ, Kalpouzos G, Andersson T, Winblad B, et al. EEG time signature in Alzheimer’s disease: functional brain networks falling apart. NeuroImage Clin. 2019;24(October):102046 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102046.

Smailovic U, Koenig T, Kåreholt I, Andersson T, Kramberger MG, Winblad B, et al. Quantitative EEG power and synchronization correlate with Alzheimer’s disease CSF biomarkers. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;63:88–95. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.11.005.

Gouw AA, Alsema AM, Tijms BM, Borta A, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, et al. EEG spectral analysis as a putative early prognostic biomarker in nondemented, amyloid positive subjects. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;57:133–42 Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0197458017301847.

Gianotti LRR, Künig G, Faber PL, Lehmann D, Pascual-Marqui RD, Kochi K, et al. Rivastigmine effects on EEG spectra and three-dimensional LORETA functional imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008;198(3):323–32 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18446328.

Adler G, Brassen S. Short-term rivastigmine treatment reduces EEG slow-wave power in Alzheimer patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2001 Jan;43(4):273–6.

Adler G, Brassen S, Chwalek K, Dieter B, Teufel M. Prediction of treatment response to rivastigmine in Alzheimer’s dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:292–4.

Moretti DV, Frisoni GB, Binetti G, Zanetti O. Comparison of the effects of transdermal and oral rivastigmine on cognitive function and EEG markers in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6(July):179.

Brassen S, Adler G. Short-term effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment on EEG and memory performance in Alzheimer patients: an open, controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(6):304–8 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14663655.

Babiloni C, Del Percio C, Bordet R, Bourriez J-L, Bentivoglio M, Payoux P, et al. Effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine on resting-state electroencephalographic rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;124(5):837–50 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23098644.

Scheltens P, Twisk JWR, Blesa R, Scarpini E, von Arnim CAF, Bongers A, et al. Efficacy of Souvenaid in mild Alzheimer’s disease: results from a randomized, controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012 Jan;31(1):225–36.

Scheltens P, Hallikainen M, Grimmer T, Duning T, Alida G, Teunissen C, et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of the glutaminyl-cyclase inhibitor PQ912 in Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2a study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):107.

van Straaten EC, Scheltens P, Gouw AA, Stam CJ. Eyes-closed task-free electroencephalography in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease: an emerging method based upon brain dynamics. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(9):86.

de Waal H, Stam CJJ, Lansbergen MMM, Wieggers RLL, Kamphuis PJGHJGH, Scheltens P, et al. The effect of souvenaid on functional brain network organisation in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised controlled study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86558 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24475144.

Attwell D, Iadecola C. The neural basis of functional brain imaging signals. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(12):621–5 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12446129.

Mosconi L, Pupi A, De Leon MJ. Brain glucose hypometabolism and oxidative stress in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:180–95 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19076441.

Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, et al. Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(7):1207–18 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19660834.

Jagust WJ, Bandy D, Chen K, Foster NL, Landau SM, Mathis CA, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative positron emission tomography core. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(3):221–9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20451870.

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–92 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21514248.

van Dyck CH, Nygaard HB, Chen K, Donohue MC, Raman R, Rissman RA, et al. Effect of AZD0530 on cerebral metabolic decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31329216.

Harrison JE, Maruff P, Schembri A, Novak P, Ondrus M, Prenn-gologranc C, Katina S. Stability, reliability, validity and relationship to biomarkers of the BRADER – a new assessment for capturing cognitive changes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther.

Harrison JE. Cognition comes of age: comments on the new FDA draft guidance for early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):61 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29958538.

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the preparation and review of this document. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Figure 1 was produced using human tissue obtained from the Edinburgh MRC Sudden death Brain Bank. The use of human tissue for post-mortem studies has been reviewed and approved by the Edinburgh Brain Bank ethics committee and the ACCORD medical research ethics committee (approval number 15-HV-016; ACCORD is the Academic and Clinical Central Office for Research and Development, a joint office of the University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian). The Edinburgh Brain Bank is a Medical Research Council-funded facility with research ethics committee (REC) approval (11/ES/0022).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

Anthony Caggiano, Nicholas Izzo, and Susan Catalano are employees or have financial interest in Cognition Therapeutics, Inc. Henrik Zetterberg has served at scientific advisory boards for Cognition Therapeutics, Roche Diagnostics, Wave and Samumed; has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Biogen and Alzecure; and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures-based platform company at the University of Gothenburg. Tara Spires-Jones is a scientific advisory board member of Cognition Therapeutics and receives collaborative grant funding from two pharmaceutical companies. John Harrison has received consultancy payments and honoraria from the following organizations in the past 2 years: 23andMe, Alzecure, Aptinyx, Athira Pharma, Axon Neuroscience, Axovant, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, CRF Bracket, Cognition Therapeutics, Compass Therapeutics, Curasen, DeNDRoN, EIP Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, GfHEu, Heptares, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Lysosome Therapeutics, Merck, Neurodyn, Neurotrack, Novartis, Nutricia, Probiodrug, Regeneron, Rodin Therapeutics, Roivant, Sanofi, Takeda, vTv Therapeutics, and Winterlight Labs. Kaj Blennow has served as a consultant or at advisory boards for Alector, Biogen, Cognition Therapeutics, Lilly, MagQu, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures-based platform company at the University of Gothenburg. Christopher van Dyck has served as a consultant or scientific advisor in the past 2 years for Roche, Eisai, and Kyowa Kirin and received grant support for clinical trials from Roche, Genentech, Eisai, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Merck, Biohaven, and Janssen. Lon Schneider reports grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Avraham, Ltd., personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Neurim, Ltd., personal fees from Neuronix, Ltd., personal fees from Cognition Therapeutics, personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from vTv, grants and personal fees from Roche/Genentech, grants from Biogen, grants from Novartis, personal fees from Abbott, and grants from Biohaven, outside the submitted work. Philip Scheltens reports consultancies with Axon Neuroscience, Cognition Therapeutics, Vivoryon, and Novartis, as well as a DSMB membership with Genentech. Michael Grundman is a paid consultant to Cognition Therapeutics. Howard Fillit has been a consultant to Axovant, vTv, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Lilly, Biogen (RTI), Roche, Genentech, Merck, Samus, Pfizer, and Alector in the past 5 years and has no conflicts that are related to this manuscript. Steven T. DeKosky is a member of the Neuroscience Advisory Board for Amgen, Chair of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board for Acumen, Chair of the Drug Monitoring Committee for Biogen, Chair of the Medical Advisory Board for Cognition Therapeutics, and Editor for Dementia for UpToDate. Martí Colom Cadena and Willem de haan declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Colom-Cadena, M., Spires-Jones, T., Zetterberg, H. et al. The clinical promise of biomarkers of synapse damage or loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Alz Res Therapy 12, 21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00588-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00588-4