Abstract

Background

Alcohol use has been identified as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline. However, some patterns of drinking have been associated with beneficial effects.

Methods and Results

To clarify the relationship between alcohol use and dementia, we conducted a scoping review based on a systematic search of systematic reviews published from January 2000 to October 2017 by using Medline, Embase, and PsycINFO. Overall, 28 systematic reviews were identified: 20 on the associations between the level of alcohol use and the incidence of cognitive impairment/dementia, six on the associations between dimensions of alcohol use and specific brain functions, and two on induced dementias. Although causality could not be established, light to moderate alcohol use in middle to late adulthood was associated with a decreased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Heavy alcohol use was associated with changes in brain structures, cognitive impairments, and an increased risk of all types of dementia.

Conclusion

Reducing heavy alcohol use may be an effective dementia prevention strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dementia is a clinical syndrome characterized by a progressive deterioration in cognitive ability and the capacity for independent living and functioning [1]. Dementia affects memory, thinking, behavior, and the ability to perform everyday activities [2], and is a leading cause of disability in older individuals [3]. Globally, dementia affects 5 to 7% of people 60 years of age or older [4]. Furthermore, the number of people with dementia globally is projected to nearly triple, from about 50 million in 2015 to 130 to 150 million in 2050 [5, 6] and this is due primarily to the epidemiological transition of the world’s population to older individuals [7], especially in lower- and middle-income countries [6].

Given the current and projected numbers of people with dementia and the associated disability, dementia is considered a major public health priority [2]. There is a potential for intervention and prevention by targeting the risk factors involved in the pathophysiological mechanisms causing dementia, such as subcortical ischemic vascular disease, amyloid angiopathy, and cortical infarction [8, 9]. These interventions and prevention strategies may be dependent on the type of dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common, followed by vascular dementia and rarer types of dementia ((including mixed types of dementia) [1]. The 2017 Lancet Commission recommended that researchers and policy makers be “ambitious about prevention” [1]; however, there was no mention of harmful alcohol use as a potential preventative target. Although there is considerable evidence of the neurotoxicity of alcohol on the brain [10,11,12], the absence of alcohol use as a potential risk factor for dementia may be due, in part, to seemingly conflicting evidence from epidemiological studies.

Recent evidence from a large-scale retrospective cohort of more than 30 million French hospital patients suggests that alcohol use may play a large role in the development of early-onset dementia [13]. Specifically, among people 64 years of age and younger, the majority of dementia cases either were classified as alcohol-related or were observed in patients in whom an alcohol use disorder (AUD) had been previously diagnosed [13]. Furthermore, a prior diagnosis of an AUD was found to be significantly associated with dementia across all age and subtype categories, and observed relative risk (RR) of dementia exceeded the RRs of all other modifiable risk factors [4, 14].

Given the impact of alcohol on dementia, our study aimed to perform a systematic scoping review of alcohol and dementia research [14, 15] to address the following questions:

-

What topics were discussed with respect to alcohol use and dementia? Considering theoretical distinctions in prior research regarding dimensions of alcohol, we searched specifically for average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of heavy episodic (binge) drinking [16]. We included AUDs as an exposure indicator.

-

Which aspects of the relationship between the onset of dementia and prior alcohol use have been systematically quantified, and what are the results of these analyses?

-

What are the results of systematic searches that do not directly quantify the association between the onset of dementia and prior alcohol use?

-

Does the relationship vary between different kinds of outcomes (types of dementia or cognitive impairment more generally)? (See also the inclusion/exclusion criteria.)

-

What methodological challenges and limitations exist in assessing the relationship between the onset of dementia and prior alcohol use?

Methods

Scope of the systematic search

Following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [17], a systematic search was performed by using OVID to identify all systematic reviews published from January 2000 to October 2017 on Medline, Embase, and PsycINFO and by using a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to alcohol use, dementia, AD, brain function, memory, and cognitive health. Additional file 1: Tables S1 to S3 in the Additional file 1 outline the exact search strategy used for each database; a PRISMA checklist is also provided in the Additional file 1. The World Alzheimer Reports were additionally used to identify potential systematic reviews [18]. A systematic search of grey literature was performed via Google but provided no contributions which fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Additional file 1: Table S5 in the Additional file 1). It is highly unlikely that systematic reviews and meta-analyses would not be published in scientific journals [19].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Reviews or meta-analyses were included if they described the systematic search process with listed databases and search terms. Narrative reviews without an explicit search strategy were excluded. In addition, included studies were restricted to systematic reviews that assessed the relationship between alcohol use and cognitive health, dementia, AD, vascular and other dementias, brain function, or memory. Systematic reviews on the association between alcohol use and brain structures were also included. Studies were included if they were published in 2000 or later in order to include only reviews which were undertaken using methodological standards similar to those used today; however, this does not mean that the original studies underlying these reviews were restricted to 2000 or later (for example, [20]) (Additional file 1).

Additional searches/sensitivity analysis

We updated our search in March 2018. In June 2018, we added a search of the same databases focussing on the Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome and including terms for “alcohol-related brain damage” or “alcohol-induced disorders in the nervous system” (Additional file 1: Table S4) based on suggestions of one anonymous peer reviewer. No additional systematic reviews or meta-analyses were found via this last search.

Extraction and processing

For each review and meta-analysis that met all inclusion criteria, we extracted all the underlying individual studies (see Additional file 1 for a complete listing). In addition, we extracted data on alcohol exposure measurements and dementia diagnoses, information about risk relations, types of studies included, age restrictions, and the conclusions of the reviews. Two researchers performed the searches and screened the results for inclusion. The review was registered under PROSPERO ([21]; CRD42017080668).

Results

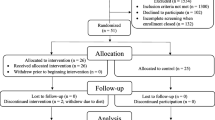

Of the 350 results from the original search, a total of 28 systematic reviews, most of which were published after 2010 [11, 20, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], met all inclusion criteria. Figure 1 outlines the results of the systematic searches.

Research topics

The following major research topics of the published systematic reviews were identified as follows:

-

the associations between the volume of alcohol consumed and the incidence of cognitive impairment/dementia, which was by far the most frequent topic of reviews (Table 1)

-

the associations between the volume and patterns of alcohol use and specific brain structures and functions [29, 35, 36, 38, 39, 43]

Associations between alcohol use and the incidence of cognitive impairment/dementia, including dose-response studies

The systematic reviews published after 2000 which studied the associations between alcohol use and the incidence of cognitive impairment or dementia were often coupled with meta-analytic summaries, typically based on cohort studies which primarily measured the effect of other modifiable risk factors, usually measured at baseline (including alcohol use), on the hazard or risk (or both) of being diagnosed with cognitive impairment or dementia or dying (or both) from dementia. See Table 1 for a summary of these reviews.

The majority of these systematic reviews indicated that there was a statistically significant association between light to moderate alcohol use and a lower risk of (i) being diagnosed with cognitive impairment and different types of dementia and (ii) dying from dementia. However, two systematic reviews found inconsistent results [37, 42]. Furthermore, chronic heavy alcohol use (defined based on the World Health Organization/European Medicines Agency definitions [48, 49] as drinking more than 60 g of pure alcohol per day for men and more than 40 g of pure alcohol per day for women) was associated with an increased risk of being diagnosed with either cognitive impairment or dementia. There also was an association found between engaging in irregular heavy drinking and the risk of being diagnosed with either cognitive impairment or dementia [29, 35]. In several reviews [24, 31, 40, 41], the potential of an interaction between alcohol use and the presence or absence of the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (a known risk factor for AD [50] and other types of dementia [51]) and the resulting risk of either cognitive impairment or dementia was also examined, albeit based on a limited number of studies with substantial heterogeneity (see also [52]).

The causality of the association between the volume and patterns of alcohol use and the development of cognitive impairment and dementia was assessed by Piazza-Gardner et al. [37], who determined that there was not sufficient evidence of a causal relationship between light to moderate drinking and a decreased risk of dementia. Overall, the level of evidence and the methodological quality of the reviews were judged to be only moderate (for a systematic evaluation of the reviews, see [23, 28]). With respect to the positive association between light and moderate drinking and vascular dementia, the underlying protective mechanisms of these patterns of use for cardiovascular outcomes were mentioned (that is, having a favorable impact on lipid levels by, for example, increasing high-density lipoprotein, and affecting atherosclerosis and inflammation via decreases in fibrinogen levels and inflammation markers [53,54,55]).

All meta-analyses (see the Additional file 1 for details) showed high levels of heterogeneity. The following limitations in assessing the relationship between alcohol use and the onset of cognitive impairment and dementia were highlighted in the systematic reviews and may explain, in part, the observed heterogeneity between studies:

-

Alcohol use was always self-reported [24, 37] and in almost all studies was assessed only once, at baseline [37].

-

There was a lack of standardization of alcohol use and of level of use categories across studies [28, 30, 33, 34, 37, 44]; some reviews used only broad descriptive categories (that is, light, moderate, and heavy alcohol use) which varied widely because of different standard alcoholic drink sizes across countries and differences in the categorization of alcohol use volumes and patterns ([56, 57]; see also [54]).

-

There was inconsistent or no control for potential confounding variables, as different risk factors or confounding variables (or both) were measured across cohort studies [24, 30, 33, 44]. Furthermore, interactions between alcohol and other risk factors, particularly tobacco smoking, may also exist but these interactions were not assessed [42].

-

Former drinkers were usually grouped with lifetime abstainers to create a control group [20, 24, 28, 31, 44], leading to a lack of control for “sick quitters” (that is, people who quit drinking because of health problems [58, 59]). However, having conducted a meta-analysis of studies in which former drinkers were categorized separately, Neafsey and Collins still observed a statistically significant association between moderate drinking and a lower risk of cognitive impairment or dementia [40]. Also, Reid et al. explicitly included only studies which separated lifetime abstainers and former drinkers [47].

-

Many studies lacked a quality assessment for various outcomes, with many different operationalizations for cognitive functioning [32], and lacked standardization for the diagnoses of different types of dementia [27, 37].

-

Some studies highlighted that the selection processes used in cohort studies may lead to underestimation of the associations between alcohol use and cognitive impairment or dementia [20]. First, many cohort studies exclude heavier drinkers [31, 60]. Second, most of the studies on alcohol use and cognitive decline/dementia concerned older subjects ([40, 44]; Table 1). Therefore, people with heavier alcohol use may have been excluded from these studies as they may have been more likely to have dementia at baseline or may have died prior to or before the end of the study because of other alcohol-attributable causes of death [16, 61]. In particular, there was an observed increase in the risk of an alcohol-attributable death at lower levels of use, such as 30 g of pure alcohol per day, and risk accelerated exponentially as average use increased [62].

-

Survivor bias may also be an issue because of missing dementia information [61] and this was not included in most reviews (exception [24]).

-

Owing to these limitations, two systematic reviews [32, 47] refrained from conducting meta-analyses because of the lack of exposure or outcome comparability across studies or both.

Associations between dimensions of alcohol use and specific brain functions

The systematic reviews that assessed the relationship between alcohol use and the resulting effects on brain structures and specific brain functioning assessed diverse associations. Verbaten tested the hypothesis that low to moderate drinking (about one to three standard alcoholic drinks) had beneficial effects on brain structure (through a review of seven magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies) and cognitive performance (through a review of six observational studies) [43]. In the MRI studies, a linear negative association was observed between the volume of alcohol consumed and brain volume and grey matter, and a positive linear association was observed between the volume of alcohol consumed and white matter volumes (in men but not in women). However, when restricted to people aged 65 years and older, low to moderate alcohol use was related to grade of white matter integrity and cognition in a curvilinear manner (that is, U-shaped). A recently published large-scale study with a follow-up at 30 years, which measured alcohol use every 5 years and involved multiple MRI images and cognitive tests, concluded that alcohol use, even at light or moderate levels, was associated with adverse brain outcomes, including hippocampal atrophy [63], thereby corroborating the general results of the systematic review by Verbaten for people under 65 years of age.

The systematic review by Montgomery et al. measured the association between heavy alcohol use in social drinkers and executive functioning [38]. The findings of the underlying studies were heterogeneous, and, when these studies were combined, no significant relationship between heavy alcohol use and executive functioning was observed; however, in a randomized control study by Montgomery et al., heavy alcohol use was significantly associated with all sub-measures of executive functioning except for memory updating [38]. Therefore, the detrimental effects of alcohol use may be mediated through a decrease in executive functioning [29, 35, 38]. Two other systematic reviews based on imaging studies [36, 39] found consistent detrimental effects of heavy alcohol use on brain structures and function. The structural effects have also been confirmed in autopsy studies [64]. Both functional and structural impacts of heavy use have been corroborated in a number of additional narrative reviews (for example, [11, 12, 65]).

Alcohol-related and alcohol-induced dementia

Heavy alcohol use has been shown to be a contributory factor, as well as a necessary factor (where the disease would not exist in the absence of alcohol), in the development of multiple brain diseases and such use may cause alcohol-related brain damage in multiple ways [11, 12, 64]. First, ethanol and its metabolite acetaldehyde have a direct neurotoxic effect, leading to permanent structural and functional brain damage [66, 67]. Second, chronic heavy alcohol use can result in thiamine deficiency by causing inadequate nutritional thiamine intake, decreased absorption of thiamine from the gastrointestinal tract, and impaired thiamine utilization in the cells, leading to Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome [68, 69]. Treatment with administration of thiamine reverses many of the Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome symptoms, although in some people certain chronic neuropsychiatric consequences of a previous thiamine deficiency persist even with appropriate treatment [68, 70]. Third, heavy alcohol use is a risk factor for other conditions that can also damage the brain: hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhotic liver disease [71], epilepsy [72], or head injury [73]. Fourth, heavy alcohol use is indirectly associated with vascular dementia because of its associations with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases such as high blood pressure, ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and stroke (for overviews, see [16, 54]). The above associations have been identified as causal [16] and have been corroborated in studies of people with AUDs [74]. Finally, heavy alcohol use is associated with lower levels of education, tobacco smoking, and depression, all of which are risk factors for dementia.

Discussion

Light to moderate alcohol use in middle to late adulthood was associated with a decreased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in numerous observational studies; however, there were contradictory findings, and owing to a number of methodological weaknesses (listed in the Results section), causality of this association could not be established. Heavy alcohol use was associated with changes in brain structures as well as with cognitive and executive impairments in observational and imaging studies. Heavy alcohol use and AUDs were also associated with an increased risk for all types of dementia. Furthermore, an alcohol consumption threshold above which cognition would be impaired (reversibly or irreversibly) may exist but has not yet been identified.

This scoping review was limited by the large amount of heterogeneity in the operationalization of outcomes and the small degree of overlap of underlying studies between reviews (Additional file 1). This heterogeneity in outcome operationalization may have contributed to the contradictory findings with respect to light to moderate drinking mentioned above. Therefore, there is also a need for the use of standardized objective measures of dementia and cognitive decline, using current consensus criteria. More rigorous studies using newer dementia, genetic, and neuroimaging biomarkers are needed to establish clearer guidelines for frontline clinicians in an era in which dementia prevention is a public and individual health priority.

The observational epidemiological studies underlying the reviews listed in Table 1 were limited because the majority of the studies were restricted to older populations (that is, late adulthood). Further research is needed in representative younger populations with long overall follow-ups and better methodologies, such as the use of imaging techniques and standardized cognitive tests at different follow-up points, combined with multiple measures of exposure at baseline and the same follow-up points (that is, expanding on the designs of [63, 75]).

Furthermore, the majority of the observational study populations are not representative of heavy alcohol users or people with AUDs, as these individuals are often excluded by design [20]. Heavy alcohol users and people with AUDs were excluded from the sampling frames [60]), were more likely to drop out [20], and were more likely to die at younger ages [74, 76,77,78]. To address these limitations, future epidemiological studies on the role of heavy alcohol use and AUDs on dementia onset could be conducted in a hospital setting where individuals with such characteristics are over-represented.

The Lancet review by Livingston et al. [1] showed that the risks of heavy drinking and AUDs for dementia have been underestimated. The French hospital cohort study, indicating that AUDs represented the highest RR for dementia of all modifiable risk factors for dementia, determined that alcohol use needs to be taken into consideration by our health and social welfare systems [13]. Replication studies from other countries would also improve the evidence base [75].

Mendelian randomization studies might aid in assessing causality [79, 80] but, to date, the findings from such studies do not indicate a causal impact of alcohol on AD [81] or cognitive functioning/impairment [82, 83]. Some of the genetic markers used for alcohol consumption are problematic as their associations with average volume of drinking and with heavy drinking occasions in overall light drinkers point in opposite directions ([80]; see also the discussion following [84]). Furthermore, cohort studies in twins may contribute to identifying genetic variations [85].

Conclusions

Given the lack of high-quality research on alcohol, AD, and cognitive functioning/impairment, future randomized prevention and secondary prevention trials with alcohol interventions are needed. Such studies would include genetic profiles, standardized cognition, mood and behavioral assessments, and quantification of structural and functional connectivity brain measures, which are all well established for dementia and found in the present scoping review to be underutilized. Such trials would be situated predominantly in the primary health-care system, where screening and brief interventions have been shown to reduce the heavy use of alcohol [86] and where many of the less severe AUDs can be treated [87]. Finally, as the addition of new analyses of existing and ongoing cohort studies will also be affected by the previously noted limitations, there is a need for future studies to address these limitations.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- AUD:

-

Alcohol use disorder

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RR:

-

Relative risk

References

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–734.

World Health Organization. Dementia: a Public Health priority 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/. Accessed 20 June 2018.

GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017, 390:1260–344.

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dementia. 2013;9:63–75.

World Health Organization. Dementia: Fact Sheet 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. Accessed 20 June 2018.

Alzeimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia 2015.

Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition. A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1971;49:509–38.

O’Brien JT, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B, Roman G, Sawada T, Pantoni L, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:89–98.

Gorelick PB. Risk factors for vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease. Stroke. 2004;35(11 suppl 1):2620–2.

Oslin D, Atkinson RM, Smith DM, Hendrie H. Alcohol related dementia: proposed clinical criteria. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:203–12.

Ridley NJ, Draper B, Withall A. Alcohol-related dementia: an update of the evidence. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5:3.

Harper C. The neuropathology of alcohol-related brain damage. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:136–40.

Schwarzinger M, Pollock BG, Hasan OSM, Dufouil C, Rehm J, QalyDays Study Group. Contribution of alcohol use disorders to the burden of dementia in France 2008-13: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e124–e32.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping Studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:141–6.

Rehm J, Gmel GE, Gmel G, Hasan OSM, Imtiaz S, Popova S, et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease - an update. Addiction. 2017;112:968–1001.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;151:264–9.

Alzeimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Reports: Home page. 2018 Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report. Accessed 18 June 2018.

Haddaway NR, Bayliss HR. Shades of grey: Two forms of grey literature important for reviews in conservation. Biol Conserv. 2015;191:827–9.

Anstey KJ, Mack HA, Cherbuin N. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2009;17:542–55.

National Insititute for Health Research. PROSPERO - International prospective register of systematic reviews. York: University of York; 2018.

Cheng C, Huang CL, Tsai CJ, Chou PH, Lin CC, Chang CK. Alcohol-related dementia: A systemic review of epidemiological studies. Psychosomatics. 2017;58:331–42.

Hersi M, Irvine B, Gupta P, Gomes J, Birkett N, Krewski D. Risk factors associated with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of the evidence. Neurotoxicology. 2017;61:143–87.

Xu W, Wang H, Wan Y, Tan C, Li J, Tan L, et al. Alcohol consumption and dementia risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:31–42.

Cao L, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Zhu XC, Tan MS, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:6144–54.

Lafortune L, Martin S, Kelly S, Kuhn I, Remes O, Cowan A, et al. Behavioural risk factors in mid-life associated with successful ageing, disability, dementia and frailty in later life: a rapid systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0144405.

Cooper C, Sommerlad A, Lyketsos CG, Livingston G. Modifiable predictors of dementia in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatr. 2015;172:323–34.

Ilomäki J, Jokanovic N, Tan ECK, Lönnroos E. Alcohol consumption, dementia and cognitive decline: An overview of systematic reviews. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10:204–12.

Thayanukulvat C, Harding T. Binge drinking and cognitive impairment in young people. Br J Nurs. 2015;24:401–7.

Xu W, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, et al. Meta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1299–306.

Alzeimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2014: Dementia and Risk Reduction 2014. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2014.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2018.

Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Gamaldo AA, Teel A, Zonderman AB, Wang Y. Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014;24:643.

Di Marco LY, Marzo A, Muñoz-Ruiz M, Ikram MA, Kivipelto M, Ruefenacht D, et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors in dementia: a systematic review of longitudinal observational cohort studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:119–35.

Pei JJ, Giron MS, Jia J, Wang HX. Dementia studies in Chinese populations. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:207–16.

Amrani L, de Backer L, Dom G. Piekdrinken op jonge leeftijd: gevolgen voor neurocognitieve functies en genderverschillen [Adolescent binge drinking: neurocognitive consequences and gender differences]. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie. 2013;55:677–89.

Monnig MA, Tonigan JS, Yeo RA, Thoma RJ, McCrady BS. White matter volume in alcohol use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addict Biol. 2013;18:581–92.

Piazza-Gardner AK, Faffud TJ, Barry AE. The impact of alcohol on Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17:133–46.

Montgomery C, Fisk JE, Murphy PN, Ryland I, Hilton J. The effects of heavy social drinking on executive function: a systematic review and meta-analytic study of existing literature and new empirical findings. Human Psychopharmacol. 2012;27:187–99.

Buhler M, Mann K. Alcohol and the human brain: a systematic review of different neuroimaging methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1771–93.

Neafsey EJ, Collins MA. Moderate alcohol consumption and cognitive risk. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:465–84.

Lee Y, Back JH, Kim J, Kim SH, Na DL, Cheong HK, et al. Systematic review of health behavioral risks and cognitive health in older adults. 2010;22:174–87.

Purnell C, Gao S, Callahan CM, Hendrie HC. Cardiovascular risk factors and incident Alzheimer disease: a systematic review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:1–10.

Verbaten MN. Chronic effects of low to moderate alcohol consumption on structural and functional propertiesof the brain: beneficial or not? Human Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:199–205.

Peters R, Peters J, Warner J, Beckett N, Bulpitt C. Alcohol, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2008;37:505–12.

Patterson C, Feightner J, Garcia A, MacKnight C. General risk factors for dementia: a systematic evidence review. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:341–7.

Weih M, Wiltfang J, Kornhuber J. Non-pharmacologic prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: nutritional and life-style risk factors. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2007;114:1187–97.

Reid MC, Boutros NN, O’Connor PG, Cadariu A, Concato J. The health-related effects of alcohol use in older persons: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2002;23:149–64.

World Health Organization. International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the development of medicinal products for the treatment of alcohol dependence. London: European Medicines Agency; 2010.

Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106–18.

Rasmussen KL, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R. Plasma levels of apolipoprotein E and risk of dementia in the general population. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:301–11.

Schipper HM. Apolipoprotein E: implications for AD neurobiology, epidemiology and risk assessment. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:778–90.

Piano MR. Alcohol’s effects on the Cardiovascular system. Alcohol Res. 2017;38:219–41.

Rehm J, Room R. The cultural aspect: how to measure and interpret epidemiological data on alcohol use disorders across cultures. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;34:330–41.

Brien SE, Ronksley PE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA. Effect of alcohol consumption on biological markers associated with risk of coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. BMJ. 2011;342:d636.

Dufour MC. What is moderate drinking? Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:5–14.

World Health Organization. International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66529/WHO_MSD_MSB_00.4.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 18 June 2018.

Fillmore KM, Stockwell T, Chikritzhs T, Bostrom A, Kerr W. Moderate alcohol use and reduced mortality risk: systematic error in prospective studies and new hypotheses. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:S16–23.

Shaper A, Wannamethee G, Walker M. Alcohol and mortality in British men: explaining the U-shaped curve. Lancet. 1988;2:1267–73.

Rehm J, Gmel G, Sempos CT, Trevisan M. Methodological issues relevant to studies of alcohol-related morbidity and mortality. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:45–7.

Binder N, Manderscheid L, Schumacher M. The combined association of alcohol consumption with dementia risk is likely biased due to lacking account of death cases. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:627–9.

Shield KD, Gmel G, Gmel GS, Mäkelä P, Probst C, Room R, et al. Lifetime risk of mortality due to different levels of alcohol consumption in seven European countries: implications for low-risk drinking guidelines. Addiction. 2017;112:1535–44.

Topiwala A, Allan CL, Valkanova V, Zsoldos E, Filippini N, Sexton C, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption as risk factor for adverse brain outcomes and cognitive decline: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2353.

Sutherland GT, Sheedy D, Kril JJ. Using autopsy brain tissue to study alcohol-related brain damage in the genomic age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1–8.

Cservenka A, Brumback T. The Burden of Binge and Heavy Drinking on the Brain: Effects on Adolescent and Young Adult Neural Structure and Function. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1111.

Kruman II, Henderson GI, Bergeson SE. DNA damage and neurotoxicity of chronic alcohol abuse. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2012;237:740–7.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The neurotoxicity of alcohol in department of health and human services, 10th special report to the U.S. Congress on alcohol and health Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2000.

Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:134–42.

Jauhar S, Jane Marshall E, Smith ID. Alcohol and cognitive impairment. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2014;20:304–13.

Day E, Bentham PW, Callaghan R, Kuruvilla T, George S. Thiamine for prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome in people who abuse alcohol. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:Cd004033.

Wijdicks EF. Hepatic Encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1660–70.

Samokhvalov AV, Irving H, Mohapatra S, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption, unprovoked seizures and epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1177–84.

Taylor LA, Kreutzer JS, Demm SR, Meade MA. Traumatic brain injury and substance abuse: A review and analysis of the literature. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2003;13:165–88.

Schwarzinger M, Thiébaut SP, Baillot S, Mallet V, Rehm J. Alcohol use disorders and associated chronic disease - a national retrospective cohort study from France. BMC Public Health. 2017;18:43.

Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, Dugravot A, Akbaraly T, Britton A, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: 23 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2927.

Shield KD, Rehm J. Global risk factor rankings: the importance of age-based health loss inequities caused by alcohol and other risk factors. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:231.

Peterson B, Kristenson H, Sternby NH, Trell E, Fex G, Hood B. Alcohol consumption and premature death in middle-aged men. Br Med J. 1980;280:1403–6.

Rehm J, Sulkowska U, Manczuk M, Boffetta P, Powles J, Popova S, et al. Alcohol accounts for a high proportion of premature mortality in central and eastern Europe. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:458–67.

Smith GD. Mendelian Randomization for Strengthening Causal Inference in Observational Studies: Application to Gene x Environment Interactions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5:527–45.

Frick U, Rehm J. Can we establish causality with statistical analyses? The example of epidemiology. In: Wiedermann W, von Eye A, editors. Statistics and causality: methods for applied empirical research. Hoboken: Wiley; 2016. p. 407–32.

Larsson SC, Traylor M, Malik R, Dichgans M, Burgess S, Markus HS, et al. Modifiable pathways in Alzheimer’s disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j5375.

Kumari M, Holmes MV, Dale CE, Hubacek JA, Palmer TM, Pikhart H, et al. Alcohol consumption and cognitive performance: a Mendelian randomization study. Addiction. 2014;109:1462–71.

Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L. Alcohol consumption and cognitive impairment in older men: a mendelian randomization study. Neurology. 2014;82:1038–44.

Holmes MV, Dale CE, Zuccolo L, Silverwood RJ, Guo Y, Ye Z, et al. Association between alcohol and cardiovascular disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ. 2014;349:g4164.

Handing EP, Andel R, Kadlecova P, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. Midlife Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Dementia Over 43 Years of Follow-Up: A Population-Based Study From the Swedish Twin Registry. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:1248–54.

Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Revs. 2018;2:CD004148.

Rehm J, Anderson P, Manthey J, Shield KD, Struzzo P, Wojnar M, et al. Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Health Care: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51:422–7.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michelle Tortolo for initial referencing and Astrid Otto for final referencing and copy editing of the text.

Funding

This publication received no funding other than the salaries to the authors by the institutions listed.

Availability of data and materials

This review was based on published literature, all of which is fully listed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JR and OSMH performed the main systematic searches and the methodological studies to assure inter-rater reliability. KDS performed the additional systematic search. JR wrote a first draft of the paper, and all authors participated in revising the draft to its current form and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This was a secondary data analysis which was based on published aggregate data. Neither informed consent to participate nor ethical approval is required.

Consent for publication

All authors have given their consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategies and studies included. (DOCX 264 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rehm, J., Hasan, O.S.M., Black, S.E. et al. Alcohol use and dementia: a systematic scoping review. Alz Res Therapy 11, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0453-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0453-0