Abstract

Background

While a considerable number of tumor-specific hypermethylated loci have been identified in renal cell cancer (RCC), DNA methylation of loci showing successive increases in normal, tumoral, and metastatic tissues could point to genes with high relevance both for the process of tumor development and progression. Here, we report that DNA methylation of a locus in a genomic region corresponding to the 3′UTR of the transcription factor T-box brain 1 (TBR1) mRNA accumulates in normal renal tissues with age and possibly increased body mass index. Moreover, a further tissue-specific increase of methylation was observed for tumor and metastatic tissue samples.

Results

Biometric analyses of the TCGA KIRC methylation data revealed candidate loci for age-dependent and tumor-specific DNA methylation within the last exon and in a genomic region corresponding to the 3′UTR TBR1 mRNA. To evaluate whether methylation of TBR1 shows association with RCC carcinogenesis, we measured 15 tumor cell lines and 907 renal tissue samples including 355 normal tissues, 175 tissue pairs of normal tumor adjacent and corresponding tumor tissue as well 202 metastatic tissues samples of lung, bone, and brain metastases by the use of pyrosequencing. Statistical evaluation demonstrated age-dependent methylation in normal tissue (R = 0.72, p < 2 × 10−16), association with adiposity (P = 0.019) and tumor-specific hypermethylation (P = 6.1 × 10−19) for RCC tissues. Comparison of tumor and metastatic tissues revealed higher methylation in renal cancer metastases (P = 2.65 × 10−6).

Conclusions

Our analyses provide statistical evidence of association between methylation of TBR1 and RCC development and disease progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Incidence of kidney and renal pelvis malignancies including renal cell cancers (RCC) have been reported to be among the top ten of newly diagnosed human cancers showing a sixth and tenth rank for males and females, respectively, in the USA [1]. While localized RCC demonstrates 5-year survival rates of more than 90%, metastasized tumors, detected in about 25% of primary RCC diagnoses, are still associated with a poor median overall survival of about 9 to 20 months [2, 3]. Previously, considerable progress has been made in the comprehensive molecular description of the clear cell variant of RCC (ccRCC) by The Cancer Genome Atlas network (TCGA) study using the kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) tissue and data collection [4]. As a result of the KIRC study branch, it now appears debatable whether mutational analyses of tumors may be of a direct translational clinical use, considering that almost every of the tumors subjected to the study turned out to exhibit an individual mutation profile [4]. In contrast, numerous studies before as well as the KIRC study itself showed that DNA methylation occur with high frequency in RCC. Genes undergoing DNA methylation and epigenetic silencing of expression frequently show loss of function and can as a result match the classical mechanism of tumor suppressor inactivation due to genetic alterations [5,6,7].

DNA methylation in normal kidney tissues has been found often to be associated with age and other epidemiologic risk factors [8,9,10] as well as renal cell cancer risk [11]. Moreover, studies found that DNA methylation can be linked to characteristics of RCC or ccRCC such as histology [12], clinical stage [13], histological grade [13], state of local or distant metastasis [13, 14], prognosis of overall survival or time of disease recurrence [6, 7, 11, 15,16,17,18] as well as prediction of therapy response [18, 19]. Hence, the search for new epigenetic marks such as DNA methylation associating with crucial steps of carcinogenesis may provide a rationale for the development of useful clinical biomarkers, starting points for subsequent targeted functional analyses as well as epigenetic-based therapies [20]. Thus biometrical analysis of genome-wide data such as from the TCGA KIRC study providing methylation information for approx. 435,000 loci in ccRCC and also normal kidney tissues substantially improves the efficacy of the search for new epigenetic candidate markers of potential use for the clinical management of ccRCC.

As a result of in silico analysis of TCGA KIRC data for age-related DNA methylation, a methylated candidate loci located in a genomic region corresponding to the 3′UTR of the T-box brain 1 (TBR1) mRNA was identified. TBR1 is a T-box transcription factor and is involved in brain development and neural migration. Neurological disorders have been attributed to homozygous as well heterozygous loss of TBR1 function due to mutations and chromosomal deletions [21]. In contrast, only two studies describe at yet association of genetic alterations and malignant diseases [22, 23]. Moreover, DNA-methylation analyses including a TBR1 locus used in the present study have been previously described for methylation-based age prediction from normal cells in saliva in a forensic context [24].

Here, we describe the measurement of relative methylation of one TBR1 locus amenable to pyrosequencing analysis within the region of interest revealing that methylation accumulates with age, associates with adiposity in normal tissues, shows tumor-specific hypermethylation and show maintenance and/or enrichment in RCC derived metastatic tissues.

Results

In silico identification of age-related methylated loci using KIRC

KIRC methylation and age data of 175 tumor adjacent normal renal tissues were subjected to Pearson correlation analysis and ranked using the obtained coefficients of correlation as a measure. Among the top 50 CpG sites identified as candidates for age-related methylation in the genome-wide biometric analysis, we identified four CpG loci annotating either to the last exon or the genomic region corresponding to the 3′UTR of the TBR1 mRNA (Fig. 1): cg05301866, cg12757011, cg06942701, and cg06488443. All candidate sites demonstrated Bonferroni-Hochberg adjusted P values of less than 1 × 10−10 and coefficients of correlation of R = 0.689–0.648 compared to a range of coefficients of correlation from R = 0.763 (first rank) to R = 0.646 (50th rank) for the top 50 candidate loci.

Genomic organization of the TBR1 gene on chromosome 2 showing two transcripts: exons and genomic regions corresponding to the 5′- and 3′UTRs of TBR1 mRNA are presented with thick and thinner boxes, respectively, distribution of CpG islands (CGI), putative target binding sites of microRNAs on corresponding TBR1 mRNA, location of candidate CpG sites (C and cg:), and location of the pyrosequencing assay (Assay) are shown. Numbers refer to the candidate CpG sites cg05301866 (1), cg06942701 (2), cg06488443 (3), and cg12757011 (4)

To narrow down the group of candidates a review of literature for known or supposed associations between gene alterations and cancer was carried out revealing the TBR1 gene as a candidate gene. Technical evaluation of candidate CpG loci identified the cg12757011 locus (chr2q24.2: pos. 162,281,112) as a favorite target for pyrosequencing analysis. UCSC table browser in silico analysis shows that the cg12757011 locus is located in a genomic region corresponding to the 3′UTR of the TBR1 mRNA. This section also includes microRNA response elements of the putatively cancer-related microRNAs miR-19, -375, -27ab, and -141/200a [25]. Genomic locations of TBR1-associated CpG islands (CGIs), the candidate CpG sites, the pyrosequencing assay and microRNA response elements (Fig. 1) as well as exemplary primary data for pyrosequencing analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1) are presented.

TBR1 methylation frequently occurs in urological cancer cell line tumor models

Relative methylation in cell lines as measured by pyrosequencing demonstrated high level methylation of the TBR1 locus in nearly all of the human cancer cell line models (Fig. 2). Six of six (100%), three of three (100%), and five of six (83%) of tumor cell lines for renal, prostate, and urothelial cancers revealed relative methylation levels of greater than 80%. Normal primary epithelial cells from kidney and prostate as well as the HB-CLS1 human bladder cancer cell line were detected with relative methylation values of 25–50%.

TBR1 DNA methylation in normal autopsy tissue shows association with age and adiposity

Methylation analysis of 355 normal autopsy renal tissue samples revealed a strong correlation of relative methylation with age of tissue donators (R = 0.849, P < 2 × 10−16). Hence statistically viewed, over 70% of the observed variance in methylation can be explained by the variable age. The regression plot shows that methylation accumulates with age exhibiting an increase of 0.25% methylation per year (Fig. 3a). Noteworthy, increased methylation is observed early as even tissues aged between 0 and 5 years demonstrated relative methylation in the range of 10–15%. We also investigated whether relative methylation in autopsy tissue specimens shows association with body mass classification for obesity of tissue donators and compared subsets of 98 samples of normal (BMI 20–25) vs. 84 samples of the adiposity group (BMI > 30). Using bivariate logistic regression analysis and age as a covariate to account for age-related effects (Fig. 3b), we found a slight but statistically significant increase in TBR1 methylation for the obesity subgroup (31.6% mean methylation) in comparison to the normal weight group (30.1% mean methylation) exhibiting only TBR1 methylation but not age as a significant variable (P = 0.019, OR = 1.11, 95%CI 1.02–1.20) in the bivariate regression model. No significant difference could be detected for tissue specimens obtained from female and male donators (P = 0.31, OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.91–1.03)

a Measurement of TBR1 methylation in normal autopsy tissue samples and correlation with age of tissue donators. A strong correlation between relative methylation levels and age was found (R = 0.849, P < 2 × 10−16) showing a slope of 0.25% methylation increase per year. b Box plot comparison of relative TBR methylation levels measured for the normal and adiposity tissue group. Notches indicate estimated confidence intervals for group medians

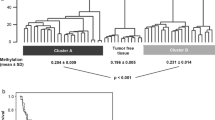

The TBR1 candidate locus is hypermethylated in renal cell cancer

To analyze whether the TBR1 candidate locus shows tumor-specific hypermethylation, we measured 175 corresponding tissue pairs of tumor adjacent normal and tumor tissue specimens (Fig. 4a). Paired tissue analysis revealed that by far the largest part of tumor tissues shows hypermethylation in tumor samples, a subset of corresponding tissue pairs did not exhibit higher methylation in tumors and a small part is characterized by hypo-methylated tumors, showing overall clear hypermethylation in tumor tissues (paired two-sided t test, P = 6.1 × 10−19).

a Comparison of paired adjacent normal (and) and tumor (Tu) tissue methylation. Lines connect paired tissue samples. Statistical comparison of paired methylation values was carried out by use of the paired t test and showed significant hypermethylation for tumor tissues (paired two-sided t test, p = 6.1 × 10−19). b Box plot comparison of relative TBR1 methylation levels observed in RCC sample tissues (Tu) and independent metastatic tissue samples (Mtx). Note that in case of multiple metastatic tissue samples mean methylation values were presented in the Mtx group. Notches indicate estimated confidence intervals for group medians

DNA methylation of TBR1 locus increases in tissues of renal cancer metastases

We further compared methylation of the TBR1 locus in a subset of 135 primary tumor tissues clinically diagnosed to be free both of lymph node and distant metastasis and 202 cancer metastatic tissues isolated from 105 renal cell cancer patients suffering from metastatic disease. Metastases investigated for TBR1 methylation originated in 142 (70%) cases from lung, brain, bone or lymph nodes (Table 3). Mean methylation values were calculated in case that two or more metastatic tissues were measured per patient and compared to the independent group of primary cancers clinically classified as negative for lymph node or distant metastasis. We found that methylation in renal metastatic tissues increased by 5.2% to a mean value of 49.4% in comparison to a mean methylation of 44.1% in primary cancer tissues (Fig. 4b, logistic regression: P = 0.009). Review of relative methylation levels in in renal metastases revealed in part substantial variation within multiple metastases isolated from a single patient (data not shown).

Association of TBR1 methylation with clinico-pathological parameters

Statistical evaluation of the candidate TBR1 locus using the evaluation tissue cohort of primary tumors did not reveal any significant relationship in bivariate logistic regression analyses for the group of all RCC or ccRCC when including age as covariate for the clinic-pathological parameters of clinical state of distant (P = 0.27 and P = 0.70 for all RCC and ccRCC groups) and lymph node (P = 0.44 and P = 0.53) metastasis, high (> = G2–3) vs. low (< = G2) histological grade (P = 0.12 and P = 0.34) and high (> = T3) vs. low (< = T2) clinical stage (P = 0.21 and P = 0.12). Considering that the candidate CpG site cg12757011 was identified by biometric analysis primarily aiming at detection of age-related DNA methylation rather than association with clinical parameters we asked whether other CpG sites in the TBR1 gene may show statistical association with adverse clinic-pathological parameters. In silico analysis using the TCGA KIRC data of 284 tumor patients then revealed that several CpG sites located in the gene body region upstream of the candidate locus show significant association with adverse clinic-pathological parameters as well as recurrence-free survival of patients (Fig. 5). So, presumably one larger group of neighbored CpG sites located between exons 3 and 6 demonstrated comparatively higher odds ratios for association with state of distant metastasis, high-stage tumors, and loss of differentiation in tumors in bivariate logistic regression analyses including age as a covariate. Correspondingly, these loci exhibited also comparatively increased hazard ratios in cox regression analyses indicating that loci statistically associated with adverse clinico-pathologic parameters were also related with shortened recurrence-free survival of patients (Fig. 5, Additional file 2: Table S1).

In silico analysis of association of CpG site methylation as reported by the TCGA-KIRC analysis with clinico-pathological parameters as well as recurrence-free survival (RFS) of patients in context with aggregated genomic organization of the TBR1 gene (TBR1), localization of CpG islands (CGI), annotated CpG sites (CpG), and pyrosequencing assay (PS). Plots show the logarithm of odds ratios (log(OR)) obtained in bivariate logistic regression analyses for association with state of metastasis, high-stage (T3 or T4) tumors, and high-grade (G2–3, G3 ) tumors for each CpG site amenable to statistical evaluation. Open circles indicate analyses exhibiting statistical significance (P < 0.01) following Bonferroni-Hochberg adjusting for multiple testing. Filled circles indicate that statistical significance has not been reached (P > 0.01). Recurrence-free survival analysis is presented by hazard ratios (HR) obtained in univariate Cox-regression analysis without adjustment for multiple testing

Loss of TBR1 mRNA expression

In silico comparison of mRNA expression using the KIRC data demonstrated an approx. 2.3-fold reduction of expression in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues (P = 0.012, paired t test).

Discussion

Identification of new methylation marks associated with tumor risk and/or progression in specific human tissues may provide the base of molecular biomarkers for diagnosis and individualized therapy approaches as well as give reasonable starting points for functional analyses of kidney cancer tumor biology. In view that approx. 80% of cancer-related methylated loci also show age-related methylation in normal tissues [26] in silico analyses of genome-wide methylation databases such as the TCGA KIRC data for renal tissues could also be a rationale for the identification of new epigenetic marks with possible relevance for renal cell cancer.

Our genome wide search in the KIRC data set identified four out of the 50 top ranking age-dependent methylated CpG sites in normal kidney tissues to be located in a genomic region corresponding to the last exon and the 3′UTR of the TBR1 mRNA. Evaluation by use of the autopsy normal tissue sample cohort revealed full confirmation of the biometric discovery study result as the candidate TBR1 CpG site demonstrated a strong and statistical robust linear relationship between DNA methylation and age of tissue donators.

Of note, comparison of normal and obesity-related tissue sample subsets suggested adiposity as an additional epidemiologic factor for higher TBR1 methylation in normal renal tissues. However, differences in mean methylation values of compared groups seem to be limited and substantial overlap is observed in both distributions of methylation values. Interestingly, we previously observed a similar result for methylation of the RASSF1 gene in normal kidney cells also discussing the possible hypothetical explanations for these findings [10]. On the other hand, methylation analyses in normal kidney tissues revealed that methylation of the TBR1 locus was found to be statistically associated with two known epidemiological risk factors in normal renal tissues. From a technical point of view, therefore our results show that biometric analysis of the TCGA KIRC data may serve not only for statistical answering of tumor-related questions but is also suited in principal for the identification of normal tissue alteration such as age- and lifestyle-associated epigenetic marks. Previous experimental studies used a subset of 1500–2000 CpG sites corresponding to several hundred genes and showed that CGI-DNA methylation in human solid normal tissues in general is often associated with age and environmental factors [27, 28]. Our results indicate that the KIRC methylation data of nominally 435,000 CpG sites are also usable for tissue-specific and genome-wide search of age-related epigenetic marks in normal kidney tissue.

Interestingly, so far, only few genes have been quantitatively characterized for age-dependent methylation in solid normal human tissues therefore limiting possibilities of comparison. Previous work of us analyzed the association of RASSF1 and SFRP1 CGI methylation and age in normal kidney tissue [11, 29]. In comparison, the observed variance in the linear regression model was by far lowest for TBR1 which might be due to the biometrical genome-wide pre-selection of candidates for highest coefficients of correlation with age. Moreover, the highest average rate of annual gain in methylation of about 0.25% was observed for TBR1 compared to RASSF1 (0.15%) and SFRP1 (0.06%). Recently, a considerable number of loci, including the TBR1–cg12757011 locus, have been analyzed to establish methylation-based age prediction from cytological saliva samples [24]. While the increase in relative methylation levels seems to be in good concordance when comparing results obtained for the age interval between 20 and 60 years for normal saliva and renal cells, apparently the normal kidney cells revealed a much higher coefficient of correlation of R = 0.85 compared to R = 0.17 in normal saliva cells.

Identification of cg12757011 as an age-related TBR1 methylation locus which is located outside of a CGI seems not meeting current hypotheses postulating age dependent intra CGI-hypermethylation while CpG loci outside of CGIs are rather expected to show hypomethylation [26, 27].

Whether methylation in age dependent methylated loci shows further increase in tumor tissues, aggressive tumors and eventually in metastatic tissues is a question of fundamental interest because the preservation or even stepwise enrichment of cells carrying the methylation mark, detected by maintenance or successive gains in relative methylation values, would suggest a contribution of the corresponding candidate gene to tumor development, tumor progression and metastasis [30]. Here, we found that both tumor and metastatic tissues show a specific increase in TBR1 methylation when compared to the respective predecessor tissues. These results are in line with a gradually enrichment of cells carrying TBR1 methylation during progression from normal to tumor tissues and tumor to metastatic tissues. Therefore, our results statistically support the view that TBR1 methylation promotes the development both of tumor cells as well as of metastatic cells growing out of primary tumor tissues.

We also questioned whether tumor progression and a concurrent gain of TBR1 methylation can be also detected within the group of primary tumors when comparing for the clinical status distant metastasis, stage and grade of tumors. However, corresponding statistical associations were not found in our cohort apparently contradicting the findings in metastatic tissues. On the other hand, two arguments probably put these findings into perspective. First, tumor heterogeneity for TBR1 epi-alterations could impede the detection of metastasis-positive tissues leading to a decreased statistical power, in particular when considering that only 16% of primary tumors were clinically classified as metastasis positive. Second, our in silico analysis demonstrated that cg12757011 is located in the 3′ flank of a region of other CpG sites showing a much more pronounced association with adverse clinic-pathological parameters as well as worse survival of patients. Therefore we assume that adaption of study design by increasing the number of primary tumors with positive status of distant metastasis together with assessment of CpG sites located in the 5′ neighborhood could improve detection of metastasis in primary kidney tumors. Taking into account that our evaluation study using the TCGA KIRC data confirmed association of TBR1 methylation with disadvantageous clinical and survival parameters our study approach comparing renal tissues from normal towards full metastatic tissue nevertheless might provide an efficient way for identification of new genes relevant for tumor development and progression.

TBR1 alterations have been found primarily in neurological disorders thus far, while information about TBR1 alterations in human cancers is sparse [21]. So, copy number variations for TBR1 have been reported for glioblastomas [22] and mutation of the TBR1 gene was found in medulloblastomas, an embryonic cancer of the brain [23]. In line with thin information about TBR1 alterations occurring in tumors, methylation of the gene has not been reported until now in the context of any human cancer to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, our results give additional evidence that TBR1 alterations play also a role in human cancers, in particular when considering that 11 out 12 cancer models representing the 3 urological tumor entities of kidney, urothelial, and prostate cancer show high TBR1 methylation. As our study provided statistical evidence which is in line with a possible contribution of TBR1 alterations in the development and progression of RCC, functional studies are required to clarify the causal relevance of TBR1 alterations for renal cancers.

Taking into account that our analysis of KIRC data also revealed a significant tumor-specific reduction of TBR1 mRNA expression and biometrical data provided by the UCSC genome browser report the presence of microRNA response elements, from a theoretical point of view epigenetic alteration of both transcriptional as well as post-transcriptional control of TBR1 mRNA expression in RCC can be considered as possible starting points for functional analyses. So tumor-specific hypermethylation and loss of mRNA expression are a characteristic of epigenetic silencing of gene expression while the presence of microRNA response elements of the miR-200 family point to a possible alteration in regulation of cellular response to hypoxia, representing one of the most important pathophysiological processes in RCC development [20, 31].

Conclusions

Our study identified a new epigenetic methylation mark in normal kidney tissue showing accumulation with age and further enrichment in tumor as well as metastatic kidney tissues, thus providing statistical evidence of association between TBR1 DNA methylation and RCC development and disease progression.

Methods

In silico analyses for candidate identification

For statistical analysis level 3 data of the TCGA KIRC HM450k methylation data set [4], the statistical software R 3.02 [32] and a x86 64 bit desktop computer platform with 32 GB RAM running under Windows 7 was used. Candidate age-dependent methylated loci were identified by Pearson correlation analyses of the normal tissue subset. Results were adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple statistical testing.

Primary cells and tumor cell lines

Renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (RPTEC) and normal primary prostatic cells (PreC) were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and renal, prostatic, and urothelial cancer cell lines RCC-MF,RCC-HS, RCC-GS, ACHN, A498, 786-O, PC-3,LN-cap, DU-145, T24, RT112, HB-CLS2, HB-CLS1, CLS439, and 5627 were obtained from cell line services (CLS, Eppelheim, Germany). Cells were grown according to the manufactures instructions presenting no more than 16 passages before DNA isolation.

Study design, tissue donator, and patients’ characteristics

To evaluate the relevance of TBR1 DNA methylation for RCC carcinogenesis, we measured four tissue cohorts including a total of 907 tissue samples. Three hundred and fifty-five fresh frozen normal renal tissue (No) samples from autopsies (Table 1) were analyzed in a cross-sectional study for the relationship of methylation and tumor risk factors age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). Tumor-specific hypermethylation was analyzed by comparison of 175 pairs of normal tumor adjacent (adN) and tumoral fresh frozen tissue (Tu) samples (Table 2). Methylation in renal metastases were analyzed in 202 RCC formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples from metastatic tissues of 105 patients isolated mostly from lung, bone, and brain (Table 3). TNM-classification and grading of tumors was carried out as described previously [18].

Nucleic acid extraction, DNA bisulfite conversion, and DNA methylation analysis

Histological analysis for tumor cell content in control sections, DNA isolation from frozen section, and punches of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples as well as bisulfite conversion of DNA were carried out as reported previously [17, 19]. DNA from cancer cell lines and primary cells was obtained using standard proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction. Methylation analysis was carried out by pyrosequencing. Primers were designed by use of the PyroMark Assay Design 2.0 software (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Pyrosequencing was performed as described recently [Tezval, 2016]. Primer sequences used for PCR and pyrosequencing were each in 5′-3′ direction, GGTGGGTTTAGGTTTTAGAGT (forward), CTCCCCCTCCTCTTTCTCTTACCTCCT (reverse), and GAGTTAATATTTTATGGTTAATGTG (sequencing). The sequence to analyze was 5′-GAGGTYGAGA TTTGGYGGGT YGGAATYGTT GTTGTTTGAT AGGATTGTTT–3′. The CpG sites analyzed were located on chromosome 2 at positions 162,281,112, ~118, ~123, ~133 (UCSC, hg19 data) in a genomic region corresponding to the 3′UTR of TBR1 mRNA (Fig. 1). PCR reactions and preparation of pyrosequencing templates were carried out as described before [33].

Statistical analyses

For analysis of age-dependent methylation Pearson correlation analysis was applied. Comparison of methylation in tumor and paired tumor adjacent normal tissues were carried out using the two-sided paired t test. Sub group comparisons for association with obesity or clinico-pathological parameters were performed by the use of univariate and bivariate logistic regression models if necessary following dichotomization as specified. Comparison of metastatic tissue samples with independent primary cancer tissues were carried out following aggregation of multiple metastasis data using calculation of the mean metastatic methylation value per patient and the two-sided t test for independent sample groups. All statistical calculations were done using R 3.02 [32].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of potentially possible impairment of data protection concerns of patients.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30 Epub 2017/01/06.

Heng DY, Choueiri TK, Rini BI, Lee J, Yuasa T, Pal SK, et al. Outcomes of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma that do not meet eligibility criteria for clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(1):149–54 Epub 2013/12/21.

Heng DY, Wells JC, Rini BI, Beuselinck B, Lee JL, Knox JJ, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol. 2014;66(4):704–10 Epub 2014/06/17.

TCGA. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499(7456):43–9 Epub 2013/06/25.

Dreijerink K, Braga E, Kuzmin I, Geil L, Duh FM, Angeloni D, et al. The candidate tumor suppressor gene, RASSF1A, from human chromosome 3p21.3 is involved in kidney tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(13):7504–9.

Morris MR, Ricketts C, Gentle D, Abdulrahman M, Clarke N, Brown M, et al. Identification of candidate tumour suppressor genes frequently methylated in renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010.

Morris MR, Ricketts CJ, Gentle D, McRonald F, Carli N, Khalili H, et al. Genome-wide methylation analysis identifies epigenetically inactivated candidate tumour suppressor genes in renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2011;30(12):1390–401.

Waki T, Tamura G, Sato M, Motoyama T. Age-related methylation of tumor suppressor and tumor-related genes: an analysis of autopsy samples. Oncogene. 2003;22(26):4128–33.

Arai E, Ushijima S, Fujimoto H, Hosoda F, Shibata T, Kondo T, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in both precancerous conditions and clear cell renal cell carcinomas are correlated with malignant potential and patient outcome. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(2):214–21.

Peters I, Vaske B, Albrecht K, Kuczyk MA, Jonas U, Serth J. Adiposity and age are statistically related to enhanced RASSF1A tumor suppressor gene promoter methylation in normal autopsy kidney tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(12):2526–32.

Atschekzei F, Hennenlotter J, Janisch S, Grosshennig A, Trankenschuh W, Waalkes S, et al. SFRP1 CpG island methylation locus is associated with renal cell cancer susceptibility and disease recurrence. Epigenetics. 2012;7(5):447–57 Epub 2012/03/16.

Costa VL, Henrique R, Ribeiro FR, Pinto M, Oliveira J, Lobo F, et al. Quantitative promoter methylation analysis of multiple cancer-related genes in renal cell tumors. BMC Cancer. 2007;7(1):133.

Urakami S, Shiina H, Enokida H, Hirata H, Kawamoto K, Kawakami T, et al. Wnt antagonist family genes as biomarkers for diagnosis, staging, and prognosis of renal cell carcinoma using tumor and serum DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(23):6989–97.

Peters I, Eggers H, Atschekzei F, Hennenlotter J, Waalkes S, Trankenschuh W, et al. GATA5 CpG island methylation in renal cell cancer: a potential biomarker for metastasis and disease progression. BJU Int. 2012;110(2 Pt 2):E144–52 Epub 2012/02/01.

Yamada D, Kikuchi S, Williams YN, Sakurai-Yageta M, Masuda M, Maruyama T, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of the potential tumor suppressor DAL-1/4.1B gene in renal clear cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(4):916–23.

Christoph F, Weikert S, Kempkensteffen C, Krause H, Schostak M, Kollermann J, et al. Promoter hypermethylation profile of kidney cancer with new proapoptotic p53 target genes and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(17):5040–6 Epub 2006/09/05.

Gebauer K, Peters I, Dubrowinskaja N, Hennenlotter J, Abbas M, Scherer R, et al. Hsa-mir-124-3 CpG island methylation is associated with advanced tumours and disease recurrence of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(1):131–8 Epub 2013/01/17.

Dubrowinskaja N, Gebauer K, Peters I, Hennenlotter J, Abbas M, Scherer R, et al. Neurofilament Heavy polypeptide CpG island methylation associates with prognosis of renal cell carcinoma and prediction of antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy response. Cancer medicine. 2014;3(2):300–9 Epub 2014/01/28.

Peters I, Dubrowinskaja N, Abbas M, Seidel C, Kogosov M, Scherer R, et al. DNA methylation biomarkers predict progression-free and overall survival of metastatic renal cell cancer (mRCC) treated with antiangiogenic therapies. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e91440 Epub 2014/03/19.

Henrique R, Luis AS, Jeronimo C. The epigenetics of renal cell tumors: from biology to biomarkers. Front Genet. 2012;3:94 Epub 2012/06/06.

Huang TN, Hsueh YP. Brain-specific transcriptional regulator T-brain-1 controls brain wiring and neuronal activity in autism spectrum disorders. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:406 Epub 2015/11/19.

Nakahara Y, Shiraishi T, Okamoto H, Mineta T, Oishi T, Sasaki K, et al. Detrended fluctuation analysis of genome-wide copy number profiles of glioblastomas using array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Neuro-oncology. 2004;6(4):281–9 Epub 2004/10/21.

Jones DT, Jager N, Kool M, Zichner T, Hutter B, Sultan M, et al. Dissecting the genomic complexity underlying medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488(7409):100–5 Epub 2012/07/27.

Hong SR, Jung SE, Lee EH, Shin KJ, Yang WI, Lee HY. DNA methylation-based age prediction from saliva: High age predictability by combination of 7 CpG markers. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2017;29:118–25 Epub 2017/04/19.

Karolchik D, Hinrichs AS, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Sugnet CW, Haussler D, et al. The UCSC Table Browser data retrieval tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D493–6 Epub 2003/12/19.

Issa JP. Aging and epigenetic drift: a vicious cycle. J Clin Investigation. 2014;124(1):24–9 Epub 2014/01/03.

Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Wrensch MR, Wiemels JL, et al. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS genetics. 2009;5(8):e1000602 Epub 2009/08/15.

Byun HM, Siegmund KD, Pan F, Weisenberger DJ, Kanel G, Laird PW, et al. Epigenetic profiling of somatic tissues from human autopsy specimens identifies tissue- and individual-specific DNA methylation patterns. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18(24):4808–17 Epub 2009/09/25.

Peters I, Rehmet K, Wilke N, Kuczyk M, Hennenlotter J, Eilers T, et al. RASSF1A promoter methylation and expression analysis in normal and neoplastic kidney indicates a role in early tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer. 2007;6(1):49.

Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447(7143):433–40.

Zhou L, Chen J, Li Z, Li X, Hu X, Huang Y, et al. Integrated profiling of microRNAs and mRNAs: microRNAs located on Xq27.3 associate with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PloS One. 2010;5(12):e15224 Epub 2011/01/22.

Team RDC. R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. 2011.

Tezval H, Dubrowinskaja N, Peters I, Reese C, Serth K, Atschekzei F, et al. Tumor specific epigenetic silencing of corticotropin releasing hormone-binding protein in renal cell carcinoma: association of hypermethylation and metastasis. PloS one. 2016;11(10):e0163873 Epub 2016/10/04.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CR and ND performed the DNA extraction, bisulfite treatment of DNA, and methylation analyses. KA, MK, ML, AG, and AB carried out selection, clinical evaluation, and sampling of renal autopsy and metastatic tissue samples. JH and ML performed selection and sampling of renal tumor tissue and corresponding tumor adjacent normal tissues. JS, IP, ST, and MAK contributed to the study design and revised the manuscript. WIA carried out histopathological examination of renal tumor samples. IP, AG, and AB collected clinical data. JS carried out biostatistical evaluation of candidate selection and data evaluation. JS, IP, JH, AS, and MAK contributed to the study design wrote and revised the manuscript. AS, ST, and MAK assisted with study design and scientific discussion. JS conceived the studies, guided the experimental work, performed statistical analyses, and prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee “Ethik-Komission an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Eberhard-Karls-Universität am Universitätsklinikum Tübingen (Head Prof. Luft)” and “Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Hochschule (Head Prof. Tröger)” approved the study (ethics votes no. 128/2003V and 1213-2011) and written informed consent was obtained from patients. Autopsy tissue samples were obtained from the department of legal medicine (Head Prof. Klintschar). No objections were raised by the local ethics committee (Head Prof. Engeli) to the anonymous analyses of autopsy tissues.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Primary data showing pyrosequencing results obtained for normal kidney tissue samples of age 3 years (A), 91 years (B), paired tumor adjacent histopathological normal (C) and tumoral (D) tissue samples and a renal cancer brain metastasis tissue sample (E) exemplarily showing overall increase of methylation in renal tissues of different normal and malignant states.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Cox regression analysis of TCGA KIRC data for for association of TBR1 CpG methylation and recurrence-free survival of patients.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Serth, J., Peters, I., Dubrowinskaja, N. et al. Age-, tumor-, and metastatic tissue-associated DNA hypermethylation of a T-box brain 1 locus in human kidney tissue. Clin Epigenet 12, 33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-020-0823-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-020-0823-x