Abstract

Objectives

Given the well-established link between hormonal contraceptives and hypertension risk, and the paucity of research on hormonal contraceptive use dynamics in this particular demographic, we hypothesize that there is a likelihood of low utilization of high-risk hormonal contraceptives among women living with hypertension in SSA. This study investigates the prevalence and factors associated with hormonal contraceptive use among women living with hypertension in the SSA.

Results

Only 18.5% of women living with hypertension used hormonal contraceptives. Hormonal contraceptive use was high among women with a higher level of education (aOR = 2.33; 95%CI: 1.73–3.14), those currently working (aOR = 1.38; 95%CI: 1.20–1.59), those who have heard about family planning on the radio (aOR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.09–1.47), listened to the radio at least once a week (aOR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.10–1.51), and those residing in rural areas (aOR = 1.32; 95%CI: 1.14–1.54). Conversely, women aged 45–49 exhibited a substantial decrease in the odds of hormonal contraceptive use (aOR = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.14–0.38) compared to younger women (15–19 years). Likewise, the odds of HCU were low among cohabiting (aOR = 0.66; 95%CI: 0.48–0.89) and previously married women (aOR = 0.67; 95%CI: 0.50–0.91) than never married women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Contraceptives continue to be a crucial public health intervention worldwide, playing a key role in preventing unintended pregnancies and the associated risks of maternal mortality and morbidity [1, 2]. The utilization of modern contraceptive methods is imperative in fulfilling the sustainable development goals (SDG) target 3.7, which emphasizes the aim for universal availability of sexual and reproductive healthcare services globally for women by 2030 [3, 4]. However, global performance towards achieving the SDG target on family planning and conception stands at 75.7%, with middle and western Africa doing less than 50% [5]. Global unmet need for contraception has declined from 15% in 1990 to 12.6% in 2020, while contraceptive prevalence (modern methods) increased from 19 to 57% during the same period [6]. The proportion of women whose need for family planning is satisfied with modern methods increased from 74% in 2000 to 77% in 2020 [7]. While there has been a global increase in contraception usage, the prevalence rate in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remains notably low [8]. The SSA region has the highest unmet need for modern contraception as over 200 million women who do not want to conceive are not using a modern contraceptive method [9, 10]. Evidence from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and Population Division showed that 15 SSA countries had more than 20% of the world’s unmet family planning needs [7].

Factors influencing the adoption of hormonal contraceptives vary across countries, regions, and cultures [11]. Numerous studies have delved into the reasons behind the non-usage of hormonal contraceptives, citing concerns like fear of side effects and lack of partner approval, age, marital status, parity, religion, support from parents, contraceptive costs, limited knowledge, peer influence, and misconceptions have shown significant associations with contraceptive use [11,12,13]. Furthermore, the continuation of hormonal contraceptive methods is linked with the availability of contraceptive methods, easy access to family planning centers, satisfaction with the current method, frequent visits to these centers, attitudes, behavior and skills of health practitioners [14,15,16]. Women are also less likely to use hormonal contraceptive methods if they have no children, are not told of family planning at a health facility, and have not heard of family planning on the television, radio, or newspaper [17, 18].

Hormonal contraceptives, comprising estrogens and/or progestins, exert cardiovascular effects, impacting blood pressure [19]. The prevalence of oral contraceptive (OC) use globally stands at 151 million users, making it the most commonly used hormonal contraceptive method [7]. Despite reduced OC doses, epidemiological evidence maintains a smaller yet noteworthy association between OC pills and hypertension [20, 21]. Combined oral contraceptives (COC) are associated with hypertension in about 2% of women, contributing to an average systolic blood pressure increase of 7–8 mmHg [22]. Afshari et al. [23] reported a 25% hypertension prevalence among women using OCs, with a 1.23 to 1.96 times higher risk compared to non-users. Women between the ages of 15 and 45 who used hormonal contraceptives within 30 days of a hypertension diagnosis exhibited a significantly elevated risk of developing hypertension [24]. Additionally, prolonged OC use during fertile years could also emerge as a notable risk factor for subsequent hypertension post-menopause [25, 26].

Despite extensive research on hormonal contraceptive use in the general population within SSA [12, 27,28,29], there is a notable scarcity of information concerning hormonal contraceptive use among women with hypertension in the sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region. Given the well-established link between hormonal contraceptives and hypertension risk, and the paucity of research on hormonal contraceptive use dynamics in this particular demographic, we hypothesize that there is a likelihood of low utilization of high-risk hormonal contraceptives among women living with hypertension in SSA. Consequently, our study aims to bridge this knowledge gap by investigating the prevalence of and factors associated with hormonal contraceptive use among women living with hypertension in the SSA.

Methods

Data source and design

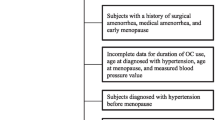

Data used for this study was from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) of twelve (12) countries in SSA. We used the most current DHS data of the respective countries (see Table 1). Specifically, we pooled data from the individual recode files of the 12 countries: Benin, Burundi, Cote d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Gabon, Gambia, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Tanzania, and Zambia. These countries were selected because they have the most recent dataset (2017–2022), and also because it contained an indicator for measuring hypertension. DHS is a comprehensive survey conducted in more than 85 low- and middle-income countries globally. The survey adopts a descriptive cross-sectional design, employing a two-stage cluster sampling method to select respondents. The detailed sampling technique has been thoroughly outlined in the literature [30]. The data collection process utilizes standardized structured questionnaires to gather information from respondents on various health and social indicators, encompassing aspects such as risky sexual behavior. In this study, we included a total sample of 7,324 women living with hypertension (see Table 1).

Measures

Outcome variable

Hormonal contraceptive use constituted the outcome variable for this study. Participants were requested to specify their current contraceptive method. Instances, where women reported using an intrauterine device (IUD) and other modern methods, were excluded due to insufficient details regarding the specific type of IUD and modern methods, respectively. Women who identified using oral contraceptives, injectable, and implants were categorized as users of hormonal contraceptives, denoted by the code “1 = yes.” Conversely, women not utilizing any hormonal contraceptives were coded as “0 = no.”

Explanatory variables

Informed by extant literature [11,12,13], as well as the availability of variables in the dataset, 15 explanatory variables were considered. These include the age of the woman, educational level, marital status, current working status, number of children ever born, having visited the health facility in the last 12 months, having heard of family planning on radio, television or in the magazines or newspapers, frequency of watching television, listening to the radio or reading newspapers or magazines, internet usage, wealth index, and place of residence. We further grouped the variables into individual and contextual level. Except for household wealth index and place of residence which were contextual level variables, the remaining variables were placed at the individual level.

Statistical analyses

The analyses were performed in STATA version 17. First, we used percentages with confidence intervals to summarize the proportion of women living with hypertension who used hormonal contraceptives. Next, the Pearson chi-square test of independence was adopted to examine the distribution of hormonal contraceptive use among hypertensive women across the explanatory variables as well as determine the association between these variables. We included only variables with p-values less than or equal to 0.05 in the regression analysis. Afterwards, a multilevel binary logistic regression analysis was used to examine the factors associated with hormonal contraceptive use among women living with hypertension. To ascertain these factors, four models were used. The first model was an empty one that measured the variation in hormonal contraceptive attributed to the primary sampling unit (PSU). We placed the individual level and contextual-level variables in Model II and III, respectively. The fourth model (Model IV) contained all the explanatory variables. The results were presented in two forms: fixed effect and random effect. The fixed effect results showed the association between the explanatory variables and hormonal contraceptive use. The results were presented using adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with their 95% CIs. On the other hand, the random effect results measure the fitness of the models as well as ensuring model comparability measured using the Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and log likelihood values, where the model with the least AIC and highest log likelihood values were selected as the best-fitted model from where the results were described and discussed. All analyses were weighted, as well as, using the STATA command “svyset” which takes into account the complex design of the survey.

Ethical considerations

Our study did not require ethical clearance as the dataset is publicly available. However, we obtained permission from the Monitoring and Evaluation to Assess and Use Results Demographic and Health Surveys (MEASURE DHS) before utilizing the dataset.

Results

Prevalence of hormonal contraceptive use among women living with hypertension

Overall, 18.5% of women living with hypertension used hormonal contraceptives. Madagascar reported the largest proportional (34.1%) use of hormonal contraceptives among this cohort while Gabon reported the lowest contraceptive use (5.0%) (see Table 1).

Distribution of hormonal contraceptive use by explanatory variables

The results in Table 2 showcase the relationship between various background characteristics of the respondents and hormonal contraceptive use. Notably, statistically significant variations were observed across different age groups. Among women aged 30–34, the highest proportion of hormonal contraceptive use was reported at 25.3% (CI: 21.8, 29.1). Additionally, higher hormonal contraceptive use was found among those with a primary education [24.4% (CI: 22.1, 26.9)], married women [21.6% (CI: 20.0, 23.3)], those who were employed [20.2% (CI: 18.7, 21.7)], and those with a parity of three [23.7% (CI: 20.6, 27.0)].

The prevalence of hormonal contraceptive use was also high among those who had heard about family planning on radio (22.5%, CI: 20.6, 24.5) and television (22.2%, CI: 20.2, 24.5) (p < 0.001). The frequency of listening to the radio also revealed a significant impact, with the highest proportion observed among those who listened at least once a week (23.0%, CI: 21.1, 25.1) (p < 0.001). Also, hormonal contraceptive use prevalence was higher among women living with hypertension who were in the richer quintile [21.6% (CI: 19.0, 24.5)] and rural residents [20.5% (CI: 18.7, 22.4)].

Factors associated with hormonal contraceptive use among the women with hypertension

Women aged 45–49 exhibited a substantial decrease in the odds of hormonal contraceptive use (aOR = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.14–0.38) compared to younger women (15–19 years). Compared to women with no formal education, those with a higher level of education (aOR = 2.33; 95%CI: 1.73–3.14) reported higher odds of using hormonal contraceptives. Marital status also played a role, with cohabiting (aOR = 0.66; 95%CI: 0.48–0.89) and previously married women (aOR = 0.67; 95%CI: 0.50–0.91) showing lower odds compared to never married women. The number of children ever born demonstrated a strong positive association with hormonal contraceptive use, with increasing odds for higher numbers of children (p < 0.001). Working women had higher odds of hormonal contraceptive use (aOR = 1.38; 95%CI: 1.20–1.59) compared to those not working (see Table 3).

Women who reported hearing about family planning on the radio exhibited increased odds of hormonal contraceptive use (aOR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.09–1.47). Also, women who listened to the radio at least once a week had higher odds of hormonal contraceptive use (aOR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.10–1.51) compared to those who did not listen at all. Additionally, residing in a rural area was associated with increased odds of hormonal contraceptive use (aOR = 1.32; 95%CI: 1.14–1.54).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the prevalence and factors associated with the use of hormonal contraceptives among women living with hypertension in SSA. Our study revealed that less than a quarter (18.5%) of women living with hypertension utilized hormonal contraceptives. The observed low utilization of hormonal contraceptives among this cohort is not surprising as previous studies [22,23,24,25,26, 31] have found a higher risk of high blood pressure among those who use this type of contraceptive. As such, the low utilization of hormonal contraceptives may be a reflection of participants’ awareness of the risk that this type of contraceptive poses to their blood pressure. Notwithstanding, we found that hormonal contraceptive utilization among women living with hypertension was influenced by age, marital status, employment status, access to health information and messages, place of residence, and parity.

Regarding age, we found that older women of reproductive age living with hypertension were significantly less likely to use hormonal contraceptives than younger women. It is plausible that older women may be more likely to be aware of their hypertension status [32]; hence, influencing them to opt for other forms of contraception than hormonal contraceptive use. Moreover, healthcare providers may be more conservative in prescribing hormonal contraceptives to older individuals with hypertension, emphasizing alternative contraceptive methods or highlighting potential health risks.

Hypertensive women with higher educational attainment were 2.3 times more likely to use hormonal contraceptives than those with no formal education. The result is consistent with Toffol et al.’s study [33] which found a positive association between educational level and hormonal contraceptive use. Similar findings have been reported in Ethiopia [34]. One plausible explanation is that women with higher educational levels may have better access to information and healthcare resources, enabling them to make informed decisions about family planning. Additionally, women with higher educational attainment may have greater financial independence, allowing them to afford and access a wider range of contraceptive options.

Our study revealed that exposure to the radio and exposure to family planning messages on the radio increased the odds of hormonal contraceptive use among women living with hypertension. This aligns with Fenta and Gebremichael’s study [24] which reported a significant positive association between media exposure and hormonal contraceptive use. In many SSA countries, hormonal contraceptives – particularly oral pills – are widely advertised by manufacturers and health advocates on radio [35, 36]. It is, therefore, possible that women living with hypertension would be more exposed to information about hormonal contraceptives, and barrier methods like condoms than any other type of contraceptives.

Consistent with findings from Bangladesh [37], we found that currently employed women living with hypertension have a 1.38 times higher likelihood of using hormonal contraceptives than those who were not working. Being employed may signify some level of stability and autonomy that enables women to make proactive decisions about their reproductive health. Furthermore, employed women may also have greater financial resources, which can facilitate access to hormonal contraceptives that may otherwise be financially burdensome. It is also possible that the workplace environment may promote discussions about family planning and reproductive health, leading to increased awareness and uptake of hormonal contraceptives among employed women living with hypertension.

Surprisingly, the findings indicate that rural residency is associated with 32% higher likelihood of using hormonal contraceptives. This is inconsistent with a previous study [37] that found lower hormonal contraceptive use among rural dwelling women. Nonetheless, the observed association aligns with Skiba et al. [38] who found a significant positive association between rural residency and hormonal contraceptive use. This is a novel finding; perhaps it could be explained from the perspective that family planning advocacy in SSA has focused much attention on rural areas. Previous studies have found hormonal contraceptives to be associated with higher hypertension risk [22,23,24]. Therefore, it is plausible that urban women possess greater access to comprehensive safety information regarding the risk that hormonal contraceptives pose, hence, contributing to reduced usage rates. Further research is required to fully understand this pattern of association. We also found high odds of hormonal contraceptive use among parous women – a result that is corroborated by prior evidence from Australia [38].

Strengths and limitations

This research addresses a significant knowledge gap in SSA in terms of hormonal contraceptives. Also, our study provided a detailed description and applied appropriate statistical analyses; thus, guaranteeing the validity and replicability of our study to similar contexts. The large sample size used helps us to generalize the findings to the wider population of SSA women living with hypertension. Yet, there are some important limitations. Causality or temporal relationships cannot be established due to the cross-sectional nature of the demographic and health survey. Additionally, it is worth noting that there is a possibility of recall bias due to the reliance on self-reported data on contraceptive use. Our analysis excluded women who used IUD, as such, there is a possibility of an underestimation in the reported prevalence of hormonal contraceptive use. Another important limitation is the fact that the DHS does not provide data on the dosage and type of hormonal contraceptive used. Also, other key confounders such as cultural beliefs and self-efficacy were not assessed due to their absence in the DHS. As we relied on a secondary dataset, we were unable to account for the actual family planning messages and content conveyed through the various media platforms. Hence, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the low utilization rate of hormonal contraceptives among women living with hypertension in SSA. We conclude that increasing age, higher educational attainment, rural residency, exposure to radio, and exposure to family planning messages are key factors that promote the use of hormonal contraceptives among this demographic. As such, tailored interventions are warranted to address barriers to access and increase awareness of contraceptive options among this vulnerable population. Additionally, healthcare providers should engage in informed discussions with patients, considering individual health profiles and preferences to promote safe and effective contraceptive choices. Further research is recommended to explore the observed rural-urban disparity in hormonal contraceptive use among hypertensive women in SSA and to inform targeted interventions effectively. Additionally, future studies should consider assessing the specific types of hormonal contraceptives, as well as changes in contraceptive methods used by women living with hypertension before, and after diagnosis of their condition.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Measure DHS repository: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COC:

-

Combined Oral Contraceptives

- OC:

-

Oral Contraceptives

References

Bahamondes L, Peloggia A. Modern contraceptives in sub-saharan African countries. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(7):e819–20.

Aryanty RI, Romadlona N, Besral B, Panggabean ED, Utomo B, Makalew R, Magnani RJ. Contraceptive use and maternal mortality in Indonesia: a community-level ecological analysis. Reproductive Health. 2021;18:1–9.

Budu E, Dadzie LK, Salihu T, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Aboagye RG, Seidu AA, Yaya S. Socioeconomic inequalities in modern contraceptive use among women in Benin: a decomposition analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):444.

United Nations Population Division. SDG Indicator 3.7.1 on Contraceptive Use [Internet]. United Nations Reports. 2022. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/sdg-indicator-371-contraceptive-use.

Kantorová V, Wheldon MC, Ueffing P, Dasgupta AN. Estimating progress towards meeting women’s contraceptive needs in 185 countries: a bayesian hierarchical modelling study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(2):e1003026.

Ntoimo L. Contraception in Africa: is the global 2030 milestone attainable? Afr J Reprod Health. 2021;25(3):9–13.

Booklet D. Family Planning and the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development (Data Booklet). Fam. Plan. 2030 Agenda Sustain. Dev (Data Booklet). 2020;10.

Takyi A, Sato M, Adjabeng M, Smith C. Factors that influence modern contraceptive use among women aged 35 to 49 years and their male partners in Gomoa West District, Ghana: a qualitative study. Trop Med Health. 2023;51(1):40.

Corey J, Schwandt H, Boulware A, Herrera A, Hudler E, Imbabazi C, King I, Linus J, Manzi I, Merrit M, Mezier L. Family planning demand generation in Rwanda: government efforts at the national and community level impact interpersonal communication and family norms. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4):e0266520.

Guttmacher Institute. Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health in Western Africa [Internet]. 2020. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/investing-sexual-and-reproductive-health-low-and-middle-income-countries.

Asiedu A, Asare BY, Dwumfour-Asare B, Baafi D, Adam AR, Aryee SE, Ganle JK. Determinants of modern contraceptive use: a cross-sectional study among market women in the Ashiaman Municipality of Ghana. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2020;12:100184.

Amoah EJ, Hinneh T, Aklie R. Determinants and prevalence of modern contraceptive use among sexually active female youth in the Berekum East Municipality, Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(6):e0286585.

Tii Kumbeni M, Tiewul R, Sodana R. Determinants of contraceptive use among female adolescents in the Nabdam District of Upper East Region, Ghana. Int J Med Public Heal. 2019;9(3):93–9.

Kraft JM, Serbanescu F, Schmitz MM, Mwanshemele Y, Ruiz CAG, Maro G, Chaote P. Factors associated with contraceptive use in sub-saharan Africa. J Women’s Health. 2022;31(3):447–57.

Bibi F, Saleem S, Tikmani SS, Rozi S. Factors associated with continuation of hormonal contraceptives among married women of reproductive age in Gilgit, Pakistan: a community-based case–control study. BMJ open. 2023;13(11):e075490.

D’Souza P, Bailey JV, Stephenson J, Oliver S. Factors influencing contraception choice and use globally: a synthesis of systematic reviews. Eur J Contracept Reproductive Health Care. 2022;27(5):364–72.

Boadu I. Coverage and determinants of modern contraceptive use in sub-saharan Africa: further analysis of demographic and health surveys. Reproductive Health. 2022;19(1):18.

Negash WD, Belachew TB, Asmamaw DB. Long acting reversible contraceptive utilization and its associated factors among modern contraceptive users in high fertility sub-saharan Africa countries: a multi-level analysis of recent demographic and health surveys. Archives Public Health. 2022;80(1):224.

Basile J, Bloch MJ. Overview of hypertension in adults. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. 2015 Dec.

Kalenga CZ, Dumanski SM, Metcalfe A, Robert M, Nerenberg KA, MacRae JM, Premji Z, Ahmed SB. The effect of non-oral hormonal contraceptives on hypertension and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Physiological Rep. 2022;10(9):e15267.

Cameron NA, Blyler CA, Bello NA. Oral contraceptive pills and hypertension: a review of current evidence and recommendations. Hypertension. 2023;80(5):924–35.

Shufelt C, LeVee A. Hormonal contraception in women with hypertension. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1451–2.

Afshari M, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Moosazadeh M. Oral contraceptives and hypertension in women: results of the enrolment phase of Tabari Cohort Study. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):224.

Kilgore KP, Lee MS, Leavitt JA, Frank RD, McClelland CM, Chen JJ. A Population-Based, Case-Control Evaluation of the Association between Hormonal Contraceptives and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;197:74–9.

Lee J, Jeong H, Yoon JH, Yim HW. Association between past oral contraceptive use and the prevalence of hypertension in postmenopausal women: the fifth (2010–2012) Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V). BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):27.

Gunaratne MD, Thorsteinsdottir B, Garovic VD. Combined oral contraceptive pill-induced hypertension and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: shared mechanisms and clinical similarities. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2021;23:1–3.

Apanga PA, Kumbeni MT, Ayamga EA, Ulanja MB, Akparibo R. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 20 African countries: a large population-based study. BMJ open. 2020;10(9):e041103.

Nolan D, Elliott-Sale KJ, Egan B. Prevalence of hormonal contraceptive use and reported side effects of the menstrual cycle and hormonal contraceptive use in powerlifting and rugby. Physician Sportsmed. 2023;51(3):217–22.

Aboagye RG, Okyere J, Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO, Budu E, Yaya S. Relationship between history of hormonal contraceptive use and anaemia status among women in sub-saharan Africa: a large population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(6):e0286392.

Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1602–13.

Araújo PX, Moreira P, Almeida DC, Souza AA. Do Carmo Franco M. oral contraceptives in adolescents: a retrospective population-based study on Blood Pressure and Metabolic Dysregulation.

Muhihi AJ, Anaeli A, Mpembeni RN, Sunguya BF, Leyna G, Kakoko D, Kessy AT, Mwanyika Sando M, Njelekela M, Urassa DP. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among young and middle-aged adults: results from a community-based survey in rural Tanzania. International journal of hypertension. 2020;2020.

Toffol E, Heikinheimo O, But A, Latvala A, Partonen T, Haukka J. Population-level indicators associated with hormonal contraception use: a register-based matched case–control study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–0.

Fenta SM, Gebremichael SG. Predictors of modern contraceptive usage among sexually active rural women in Ethiopia: a multi-level analysis. Archives Public Health. 2021;79(1):1–0.

Dwomoh D, Amuasi SA, Amoah EM, Gborgbortsi W, Tetteh J. Exposure to family planning messages and contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in sub-saharan Africa: a cross-sectional program impact evaluation study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):18941.

Beson P, Appiah R, Adomah-Afari A. Modern contraceptive use among reproductive-aged women in Ghana: prevalence, predictors, and policy implications. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:1–8.

Islam AZ, Mondal MN, Khatun ML, Rahman MM, Islam MR, Mostofa MG, Hoque MN. Prevalence and determinants of contraceptive use among employed and unemployed women in Bangladesh. Int J MCH AIDS. 2016;5(2):92.

Skiba MA, Islam RM, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Hormonal contraceptive use in Australian women: who is using what? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59(5):717–24.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Measure DHS for granting us free access to the dataset used in this study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JO, RGA and CA conceived and designed the study. JO, RGA and CA contributed to the design of the analysis. RGA performed the formal analysis and provided methodological insights. JO, RGA, CA, AKD, SS and KSD drafted the initial manuscript. KSD supervised the research. All authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript for submission. JO had the responsibility of submitting the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

None declared.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was not required for this study as we utilized publicly available data from the DHS dataset. The datasets were obtained from the DHS Program following completion of the necessary registration process and approval for their use. We adhered to all ethical guidelines pertaining to the utilization of secondary datasets in research publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Okyere, J., Aboagye, R.G., Ayebeng, C. et al. Hormonal contraceptive use among women living with hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from 12 countries. BMC Res Notes 17, 167 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-024-06830-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-024-06830-8