Abstract

Background

Pentalogy of Cantrell is a rare syndrome, first described by Cantrell and co-workers in 1958. The syndrome is characterized by the presence of five major congenital defects involving the diaphragm, abdominal wall, the diaphragmatic pericardium, lower sternum and various congenital intra-cardiac abnormalities. The syndrome has never been reported in Tanzania, although may have been reported from other African countries. Survival rate of the complete form of pentalogy of Cantrell is as low as 20%, but recent studies have reported normal growth achieved by 6 years of age where corrective surgeries were done; showing that surgical repair early in life is essential for survival.

Case presentation

The African baby residing in Tanzania was referred from a district hospital on the second day of life. She was noted to have a huge omphalocele and ectopia cordis covered by a thin membrane, with bowels visible through the membrane and the cardiac impulse visible just below the epigastrium. Despite the physical anomaly, she appeared to saturate well in room air and had stable vitals. Her chest X-ray revealed the absence of the lower segments of the sternum and echocardiography showed multiple intra-cardiac defects. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell was reached. On her fifth day of life, the neonate was noted to have signs of cardiac failure characterized by easy fatigability and restlessness during feeding. Cardiac failure treatment was initiated and she was discharged on parents’ request on the second week of life. Due to inadequate facilities to undertake this complex corrective surgery, arrangements were being made to refer her abroad. In the meantime, her growth and development was satisfactory until the age of 9 months, when she ran out of the medications and succumbed to death. Her parents could no longer afford transport cost to attend the monthly clinic visits, where the infant was getting free medication refill.

Conclusions

The case reported here highlights that in resource limited settings; poor outcome in infants with complex congenital anomalies is a function of multiple factors. However, we believe that surgery would have averted mortality in this 9-month-old female infant. We hope to be able to manage these cases better in future following the recent establishment of cardiac surgery facilities at Muhimbili National Hospital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pentalogy of Cantrell is a rare congenital anomaly, first described by Cantrell et al. in 1958 [1]. It occurs in 5.5 infants per 1,000,000 live births, globally. It is defined by the presence of five major defects, involving (1) the midline supraumbilical abdominal wall, (2) lower sternum, (3) anterior diaphragm, (4) diaphragmatic pericardium and (5) the heart (intracardiac defects) [1].

The cause of pentalogy of Cantrell is not clearly known and it is unclear whether it represents an extreme spectrum of midline disorders, since it shares some features with an X-linked dominant midline defect (thoracoabdominal syndrome) and has been reported to co-exist with other midline disorders [2–9]. In addition to classic anomalies described by Cantrell et al., few cases have been reported in co-existence with other syndromes such as Edwards’s and Goltz–Gorlin syndrome [10–12]. Similarly, other structural anomalies including craniofacial [2, 13] (e.g. cleft palate, supernumerary nares), central nervous system [8, 14–16] (e.g. hydrocephalus and neural tube defects), skeletal [12, 17–19] and abdominal abnormalities have been reported [20–23].

Surgical intervention to repair the defects is the treatment of choice and successful surgery has been reported despite post-operative complications. The prognosis depends on the severity of the cardiac defects [24–29]. We are reporting this case because pentalogy of Cantrell has never been reported in Tanzania and we are highlighting the challenges we faced while managing this case.

Case report

An African infant aged 9 months, residing in Tanzania was first seen at the age of 2 days in our newborn unit of Muhimbili National hospital. This infant had been referred from Rufiji District Hospital (about 173 km apart) because of an abnormally positioned heart and an abdominal wall defect. The defect was noticed by the mother soon after delivery and was confirmed by the attending midwives.

The baby was born normally at term after an uneventful pregnancy. There was no history of consanguinity or exposure to obviously recognized teratogenic substances. The mother was on routine hematinic as per the antenatal care program in Tanzania. However, there was no antenatal sonography done at anytime during her pregnancy. The father was 40 years old and the mother was 26 years old when the baby was born. Parents are healthy, with no family history suggestive of birth defects, and they are both African peasants residing in rural Tanzania.

On initial examination, the infant was alert, with no pallor, cyanosis or jaundice and the anthropometric examination was normal for gestational age.

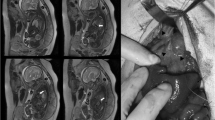

There was an obvious lower chest wall defect with cardiac pulsation visible at the epigastrium covered by a thin membrane. The manubrium was palpable but the sternal body was not appreciated and there was a large omphalocele measuring 15 × 10 cm, extending proximally to the epigastrium, covered by a thin membrane and dark surrounding skin (Fig. 1). There were no other congenital malformations detected.

Her respiratory rate was 44 breaths per minute and she was saturating at 98% in room air.

She had a heart rate of 152 beats per minute, with the apex beat palpable over the epigastrium and a systolic thrill felt at the epigastrium. There was a diffuse pan systolic murmur grade 4/6 heard over the epigastrium and other systems were essentially normal.

Her chest radiograph showed a normal manubrium-sternum and lungs, with a displaced cardiac shadow (Fig. 2).

The electrocardiogram was not done because the machine was out of order. A transthoracic M-mode two-dimensional (2D) and Doppler echocardiogram were done using Toshiba Echo machine with a 5MHZ transducer. The report showed an intact pericardium, moderate to large ventricular septal defect (VSD) measuring 6 mm with a left to right shunt, a large atrial septal defect (ASD) measuring 7 mm, with a left to right shunt. Based on these findings a conclusion of complete atrioventricular canal defect was made.

Her abdomino-pelvic ultrasound showed an anterior abdominal wall herniation at the epigastrium with cardiac pulsation.

Computerized tomography (CT) scan findings showed the absence of the mid portion and distal segment of the sternum, presence of an anterior abdominal wall defect with protrusion of the bowel loops into the thoracic cavity and a cardiac shadow noted at the epigastrium (Fig. 3).

With the clinical presentation and investigation findings reported, we arrived at a diagnosis of class II pentalogy of Cantrell, based on the presence of four (midline supra-umbilical abdominal wall defect, a defect of the lower sternum, a deficiency of the anterior diaphragm and congenital intra-cardiac defects) out of five features of the Tayoma classification [30].

The infant was treated with furosemide 1 mg/kg twice a day and spironolactone 1 mg/kg twice a day to control the heart failure, while awaiting corrective surgical treatment. Parents requested for discharge on financial grounds, as both were peasants and had no other source of income. We continued to follow up the infant monthly in our outpatient clinic, while processing the referral abroad for corrective surgery. During these visits the medication refill was offered free of charge and from parents’ self-report it was determined that adherence to medication was good. Her milestones were normal and growth adequate until the age of 8 months when she missed a clinic visit and ran out of medication for about 1 week. Parents could not afford the transport cost to bring the infant for the follow up clinic visits; hence she could not get a refill. While out of medication, the distress during breastfeeding returned, and parents had to borrow money to bring the child to the hospital. As the infant resumed her medication, the symptoms improved tremendously. However, at the age of 9 months before plans for referral abroad for corrective cardiac surgery could be finalized, she died suddenly at home. The immediate cause of death could not be determined since an autopsy was not done and the information was received from parents a week after she passed away. The limited facilities for complex paediatric cardiac surgery in our hospital and parents’ financial constraints were among the factors that contributed to the early death of the infant (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Pentalogy of Cantrell was first described by Cantrell, et al. in 1958, based on the presence of a midline supra-umbilical abdominal wall defect, a defect of the lower sternum, a deficiency of the anterior diaphragm, a defect in the diaphragmatic pericardium and congenital intra-cardiac defects [1].

Cantrell et al. suggested that the pattern of malformation in this syndrome might be a result of defective formation and differentiation of the ventral mesoderm at about 14–18 days of gestation [1]. Failure of the development of a mesoderm segment results in diaphragmatic, pericardial and intracardiac defects; whereas sternal and abdominal wall defects result from failure of paired primordial structures to migrate to their appropriate locations [1].

Based on the 60 cases reviewed by Tayoma, the syndrome is classified as complete or incomplete according to the number of malformations present [30].

Class 1 definite diagnosis and all five defects are present.

Class 2 probable diagnosis, if the four defects are present including: intracardiac and ventral abdominal wall defects.

Class 3 incomplete expression, with the various combinations of defects present and includes a sternal abnormality.

A recent review of cases of pentalogy of Cantrell reported from 1998 to 2007 shows the complete form to be more common, accounting for more than half of the cases. Of the 58 patients reviewed by Van Horn et al., 39 patients had intracardiac anomalies [31]. Congenital intracardiac anomalies are consistent elements of this syndrome, and Cantrell et al. reported VSD in almost all cases, ASD in about half of cases, tetralogy of Fallot and left ventricular diverticulum each present in one-fifth of the patients [1].

Based on our investigation results we classified the patient to have the class II form of the syndrome due to the presence of four defects including: midline supraumbilical abdominal wall defect, a defect of the lower sternum and complex intracardiac defects, with an intact pericardium. Since it is very rare to have an intact pericardium and ectopia cordis we may have missed the pericardial defect, which would put the patient in the class I form of the syndrome. However, Pachajoa et al. had also described a case with an absent diaphragmatic pericardial defect in presence of a midline defect, upper abdominal wall abnormality, lower sternal defect and an anterior diaphragmatic defect [32]. The intracardiac defects detected in this patient included VSD and ASD. The presence of these defects is similar to the case described by Ootaki et al., however, in their case the patient had the complete form of Pentalogy of Cantrell and successful surgery was done at age of 7 months [25]. Similarly Wen et al. described an incomplete form of pentalogy of Cantrell with ASD and VSD. However, contrary to the case presented here, double outlet right ventricle, transposition of great arteries and pulmonary stenosis were additional findings and it was not reported if surgery was done; but the patient was last seen at the age of 4.7 years [33].

Our case could have had a relatively better outcome since she had an incomplete form of the syndrome. Previous reports suggest that, mortality is higher in infants with the complete form and associated extra cardiac anomalies whilst patients with ectopia cordis with intracardiac defects have a favorable outcome [31, 34].

With advancement in medical knowledge and technology, patients with complex intracardiac defects can survive longer beyond 6 years of age with normal growth and development [27, 33–35]. A child with the incomplete form of pentalogy of Cantrell without intracardiac defects was reported to have corrective surgery at 11 years of age and a more mild form of the syndrome was seen in an adult case [36, 37].

In the past 5 years, 23 new cases of pentalogy of Cantrell were published in different English journals and could be retrieved through the PubMed database. Out of these cases approximately 21 (91%) were reported to have survived by the time their case reports were written. In these cases the median age at their last contact was 10 months (ranging between 4 days to 5 years) [12, 25, 27, 33–47].

Prenatal diagnosis can be done using qualified and experienced obstetric ultra sonographers as early as 10 weeks of gestation using the traditional two dimensional (2D) imaging sonography; at which stage an omphalocele and ectopia cordis are common findings [48–54]. While a 3D imaging sonography may be required for the diagnosis of certain fetal anomalies, the diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell can sufficiently be made with a traditional 2D imaging sonography [49, 51, 52, 54].

Obstetric ultrasound is indicated as a standard of care for routine evaluation of pregnant women in Tanzania, where majority of facilities have 2D imaging sonography machines. However, in our case prenatal ultrasound was not done at any point during the pregnancy, thus we missed the opportunity for prenatal counseling and early referral of this child.

Conclusions

The case reported here highlights that poor outcome in infants with pentalogy of Cantrell is inevitable if early intervention with corrective cardiac surgery for these patients is not offered. Palliation with cardiac failure treatment requires good adherence, which may be may be affected by various factors such as socioeconomics. We believe that early surgery would have averted mortality in this infant and this has stimulated us to take a more aggressive approach with a 2-month old infant with a similar condition and for who we were able to fast track the referral arrangements. We hope to be able to manage these cases better in future following the recent establishment of the cardiac surgery facilities in our hospital.

Abbreviations

- 2D:

-

two dimensional

- 3D:

-

three-dimensional

- ASD:

-

atrial septal defect

- CT:

-

computerized tomography

- VSD:

-

ventricular septal defect

- MHZ:

-

megahertz

References

Cantrell JR, Haller JA, Ravitch MM (1958) A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet 107(5):602–614

Carmi R, Boughman JA (1992) Pentalogy of Cantrell and associated midline anomalies: a possible ventral midline developmental field. Am J Med Genet 42(1):90–95

Correa-Rivas MS, Matos-Llovet I, Garcia-Fragoso L (2004) Pentalogy of Cantrell: a case report with pathologic findings. Pediatr Dev Pathol Off J Soc Pediatr Pathol Paediatr Pathol Soc. 7(6):649–652

Hernandez Castro F, Cortes Flores R, Ochoa Torres MA, Hernandez Herrera RJ, Luna Garcia S (2006) Prenatal diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell associated to bilateral cleft lip A case report. Ginecol y Obstet de Mex. 74(10):546–550

Egan JF, Petrikovsky BM, Vintzileos AM, Rodis JF, Campbell WM (1993) Combined pentalogy of Cantrell and sirenomelia: a case report with speculation about a common etiology. Am J Perinatol 10(4):327–329

Kachare MB, Patki VK, Saboo SS, Saboo SH, Ahlawat K, Saboo SS (2013) Pentalogy of Cantrell associated with exencephaly and spinal dysraphism: antenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Case report. Med Ultrason 15(3):237–239

Peer D, Moroder W, Delucca A (1993) Prenatal diagnosis of the pentalogy of Cantrell combined with exencephaly and amniotic band syndrome. Ultraschall in der Medizin (Stuttgart, German: 1980) 14(2):94–95

Dane C, Dane B, Yayla M, Cetin A (2007) Prenatal diagnosis of a case of pentalogy of Cantrell with spina bifida. J Postgrad Med 53(2):146–148

Parvari R, Weinstein Y, Ehrlich S, Steinitz M, Carmi R (1994) Linkage localization of the thoraco-abdominal syndrome (TAS) gene to Xq25-26. Am J Med Genet 49(4):431–434

Fox JE, Gloster ES, Mirchandani R (1988) Trisomy 18 with Cantrell pentalogy in a stillborn infant. Am J Med Genet 31(2):391–394

Hou YJ, Chen FL, Ng YY, Hu JM, Chen SJ, Chen JY et al (2008) Trisomy 18 syndrome with incomplete Cantrell syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol 49(3):84–87

Smigiel R, Jakubiak A, Lombardi MP, Jaworski W, Slezak R, Patkowski D et al (2011) Co-occurrence of severe Goltz-Gorlin syndrome and pentalogy of Cantrell—Case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet Part A 155A(5):1102–1105

Oudesluijs G (2011) Pentalogy of Cantrell and supernumerary naris. Genet Couns (Geneva, Switzerland) 22(3):305–307

Polat I, Gul A, Aslan H, Cebeci A, Ozseker B, Caglar B et al (2005) Prenatal diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell in three cases, two with craniorachischisis. J Clin Ultrasound JCU. 33(6):308–311

Atis A, Demirayak G, Saglam B, Aksoy F, Sen C (2011) Craniorachischisis with a variant of pentalogy of Cantrell, with lung extrophy. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 30(6):431–436

Doganay S, Kantarci M, Tanriverdi EC (2008) Pentalogy of cantrell with craniorachischisis: MRI and ultrasonography findings. Ultraschall in der Medizin (Stuttgart, Germany: 1980) 29(Suppl 5):278–280

Uygur D, Kis S, Sener E, Gunce S, Semerci N (2004) An infant with pentalogy of Cantrell and limb defects diagnosed prenatally. Clin Dysmorphol 13(1):57–58

Pivnick EK, Kaufman RA, Velagaleti GV, Gunther WM, Abramovici D (1998) Infant with midline thoracoabdominal schisis and limb defects. Teratology 58(5):205–208

Jagtap SV, Shukla DB, Jain A, Jagtap SS (2014) Complete pentalogy of Cantrell (POC) with phocomelia and other associated rare anomalies. J Clin Diagn Res 8(5):FD04–FD05. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/7648.4345

Rashid RM, Muraskas JK (2007) Multiple vascular accidents: pentalogy of Cantrell in one twin with left sided colonic atresia in the second twin. J Perinat Med 35(2):162–163

Ludwig K, Salmaso R, Cosmi E, Iaria L, De Luca A, Margiotti K et al (2012) Pentalogy of cantrell with complete ectopia cordis in a fetus with asplenia. Pediatr Dev Pathol Off J Soc Pediatr Pathol Paediatr Pathol Soc 15(6):495–498

Bittmann S, Ulus H, Springer A (2004) Combined pentalogy of Cantrell with tetralogy of Fallot, gallbladder agenesis, and polysplenia: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 39(1):107–109

Pollio F, Sica C, Pacilio N, Maruotti G, Mazzarelli L, Cirillo P et al (2003) Pentalogy of Cantrell: first trimester prenatal diagnosis and association with multicystic dysplastic kidney. Minerva Ginecol 55(4):363–366

Korver AM, Haas F, Freund MW, Strengers JL (2008) Pentalogy of Cantrell: successful early correction. Pediatr Cardiol 29(1):146–149

Ootaki Y, Strainic J, Ungerleider RM (2011) Pentalogy of Cantrell with double-outlet right ventricle: a case of surgical correction. Cardiol Young 21(2):235–237

Alguacil AF, Navarro PG, Benitez Linero I, Ontanilla Lopez A (2012) Giant omphalocele correction in a patient with pentalogy of Cantrell. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 59(1):51–54

Sakasai Y, Thang BQ, Kanemoto S, Takahashi-Igari M, Togashi S, Kato H et al (2012) Staged repair of pentalogy of Cantrell with ectopia cordis and ventricular septal defect. J Card Surg 27(3):390–392

O’Gorman CS, Tortoriello TA, McMahon CJ (2009) Outcome of children with Pentalogy of Cantrell following cardiac surgery. Pediatr Cardiol 30(4):426–430

Zhang X, Xing Q, Sun J, Hou X, Kuang M, Zhang G (2014) Surgical treatment and outcomes of pentalogy of Cantrell in eight patients. J Pediatr Surg 49(8):1335–1340

Toyama WM (1972) Combined congenital defects of the anterior abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart: a case report and review of the syndrome. Pediatrics 50(5):778–792

Van Hoorn JH, Moonen RM, Huysentruyt CJ, van Heurn LW, Offermans JP, Mulder AL (2008) Pentalogy of Cantrell: two patients and a review to determine prognostic factors for optimal approach. Eur J Pediatr 167(1):29–35

Balderrábano-Saucedo N, Vizcaíno-Alarcón A, Sandoval-Serrano E, Segura-Stanford B, Arévalo-Salas LA, de la Cruz LR et al (2011) Pentalogy of Cantrell: forty-two years of experience in the Hospital Infantil de Mexico Federico Gomez. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2(2):211–218

Gao Z, Duan QJ, Zhang ZW, Li JH, Ma LL, Ying LY (2009) Prognosis of pentalogy of Cantrell depends mainly on the severity of the intracardiac anomalies and associated malformations. Eur J Pediatr 168(11):1413–1414

Wen L, Jun-lin L, Jia H, Dong Z, Li-guang Z, Shu-hua D et al (2011) Cantrell syndrome with complex cardiac malformations: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 46(7):1455–1458

Dixit M, Gan M, Mohapatra R, Johari R, Dayal A, Vagrali A et al (2009) Pentalogy of Cantrell: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc 107(9):647–648

Magadum S, Shivaprasad H, Dinesh K, Vijay K (2013) Incomplete Cantrell’s pentalogy—a case report. Indian J Surg 75(Suppl 1):350–352

Tuluce K, Gurgun C, Yavuzgil O, Ceylan N, Tuluce SY (2012) Two different pentalogies in an adult patient: a pentalogy of Cantrell associated with a pentalogy of Fallot. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 13(10):878–879

Manieri S, Adurno G, Iorio F, Tomasco B, Vairo U (2013) Cantrell’s Syndrome with left ventricular diverticulum: a case report. Minerva Pediatr 65(1):93–96

Pachajoa H, Barragan A, Potes A, Torres J, Isaza C (2010) Pentalogy of Cantrell: report of a case with consanguineous parents. Biomedica revista del Instituto Nacional de Salud 30(4):473–477

Santiago-Herrera R, Ramirez-Carmona R, Criales-Vera S, Calderon-Colmenero J, Kimura-Hayama E (2011) Ectopia cordis with tetralogy of Fallot in an infant with pentalogy of Cantrell: high-pitch MDCT exam. Pediatr Radiol 41(7):925–929

Unal S, Cakmak Celik F, Ozaydin E, Kacar A, Gunal N (2009) A newborn with pentalogy of Cantrell and pulmonary hypoplasia. Anadolu kardiyoloji dergisi : AKD = the Anatolian. J Cardiol 9(6):519–520

Singh N, Bera ML, Sachdev MS, Aggarwal N, Joshi R, Kohli V (2010) Pentalogy of Cantrell with left ventricular diverticulum: a case report and review of literature. Congenit Heart Dis 5(5):454–457

Damry N, Pather S, Milani SM (2011) Pentalogy of Cantrell demonstrated by computed tomography in an infant. Cardiol Young 21(6):692–694

Kinoshita M, Park S, Shiraishi T, Ueno S (2012) Thoracoabdominoplasty with umbilicoplasty for Cantrell’s syndrome. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 46(5):367–370

Marino AL, Levy RJ, Berger JT, Donofrio MT (2011) Pentalogy of Cantrell with a single-ventricle cardiac defect: collaborative management of a complex disease. Pediatr Cardiol 32(4):498–502

Tan LO, Lim SY, Sharif F (2012) A ‘One in a million’ case of pulsating thoracoabdominal mass. BMJ Case Rep 2012. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007029

Wan JY, Zhao SH, Jiang SL (2012) Pentalogy of Cantrell associated with a double-outlet right ventricle. Chin Med J 125(18):3359–3360

Suehiro K, Okutani R, Ogawa S, Nakada K, Shimaoka H, Ueda M et al (2009) Perioperative management of a neonate with Cantrell syndrome. J Anesth 23(4):572–575

Gun I, Kurdoglu M, Mungen E, Muhcu M, Babacan A, Atay V (2010) Prenatal diagnosis of vertebral deformities associated with pentalogy of Cantrell: the role of three-dimensional sonography? J Clin Ultrasound JCU 38(8):446–449

Desselle C, Herve P, Toutain A, Lardy H, Sembely C, Perrotin F (2007) Pentalogy of Cantrell: sonographic assessment. J Clin Ultrasound JCU 35(4):216–220

Rodgers EB, Monteagudo A, Santos R, Greco A, Timor-Tritsch IE (2010) Diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell using 2- and 3-dimensional sonography. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med 29(12):1825–1828

Murata S, Nakata M, Sumie M, Mastsuabra M, Sugino N (2009) Prenatal diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell with craniorachischisis by three-dimensional ultrasonography in the first trimester. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 48(3):317–318

Rossi A, Forzano L, Veronese P, Fachechi G, Marchesoni D (2011) Incomplete pentalogy of Cantrell during first trimester of pregnancy. Minerva Ginecol 63(4):399–400

Sepulveda W, Wong AE, Simonetti L, Gomez E, Dezerega V, Gutierrez J (2013) Ectopia cordis in a first-trimester sonographic screening program for aneuploidy. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med 32(5):865–871

Authors’ contributions

HN participated in the diagnosis and management of the patient, conceptualized the case report and drafted the initial manuscript and the final manuscript. SP and EA participated in the diagnosis, management and follow up of the patient and participated in revising the manuscript. AM and KM participated in the diagnosis and provided expertise in neonatal and perinatal aspects of this case and reviewed the initial manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the parents who gave us permission to use the child’s information for publication and we also thank the other doctors and nurses who provided care for this patient during her hospital stay and follow up visits. This article has no funding source.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of this infant for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Naburi, H., Assenga, E., Patel, S. et al. Class II pentalogy of Cantrell. BMC Res Notes 8, 318 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1293-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1293-7