Abstract

Background

Epidemiologic studies suggest an association between vitamin D deficiency and atopic diseases, including asthma. The objective of this study was to systematically review the benefits and harms of vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma.

Methods

We used standard Cochrane systematic review methodology. The search strategy included an electronic search in February 2013 of MEDLINE and EMBASE. Two reviewers completed in duplicate and independently study selection, data abstraction, and assessment of risk of bias. We pooled the results of trials using a random-effects model. We assessed the quality of evidence by outcome using the GRADE methodology.

Results

Four trials with a total of 149 children met eligibility criteria. The trials had major methodological limitations. Given the four studies reporting on asthma symptoms used different instruments to measure that outcome, we opted not to conduct a meta-analysis. Three of those studies reported improvement in asthma symptoms in the vitamin D supplemented group study, while the fourth reported no effect (very low quality evidence). For the lung function outcome, a meta-analysis of two trials assessing post treatment FEV-1 found a mean difference of 0.54 liters per second (95% CI -5.28; 4.19; low quality evidence). For the vitamin D level outcome, a meta-analysis of three trials found a mean difference of 6.56 ng/ml (95% CI -0.64; 13.77; very low quality evidence).

Conclusions

The available very low to low quality evidence does not confirm or rule out beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma. Large-scale, well-designed and executed randomized controlled trials are needed to better understand the effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in children with asthma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood. Its prevalence has been steadily increasing worldwide over the past few decades, along with that of atopic diseases in general. This has been most apparent in the developed countries [1-3]. The reasons for this increase have not been well defined and are the subject of extensive research. They are thought to include changes in environment and lifestyle, including nutritional patterns [4].

Of the nutrients that have been studied, vitamin D has received particular attention. Besides its known effects on bone metabolism, vitamin D seems to play a number of other roles in the body, including an important immunoregulatory function [5,6]. Experimental and epidemiologic studies have tried to establish an association between vitamin D and asthma and atopic diseases. The bulk of the evidence suggested a protective effect [7-9], although some reports did show a deleterious effect of vitamin D on atopic diseases [10,11]. A number of interventional studies have been undertaken or are currently underway to assess the effect of vitamin D supplementation on asthma.

The objective of this study was to systematically review the benefits and harms of vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma.

Methods

Protocol and registration

We registered the systematic review protocol with PROSPERO prior to starting the review process (CRD42013004204) [12].

Eligibility criteria for considering studies for this review

The eligibility criteria were:

-

Types of studies: randomized controlled trial;

-

Types of participants: children aged less than 18 years with asthma. We did not consider other kinds of allergic conditions;

-

Types of interventions: vitamin D supplementation, without restrictions regarding dose (e.g., high or low), route of administration (e.g., oral, parenteral) or dosage interval (e.g., daily, weekly). The comparator was no vitamin D supplementation or placebo;

-

Types of outcome measures: asthma related symptoms (e.g., nighttime awakenings, interference with normal activity, short-acting beta2-agonist use for symptom control), exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids or hospitalization, mortality, quality of life (measured using a validated instrument such as the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ)), and vitamin D related side effects (e.g., nausea/vomiting, constipation, loss of appetite).

We did not exclude studies based on language or date of publication.

Search strategy

We designed the search strategy with the help of a medical librarian. The main search strategy consisted of searching the following electronic databases using the OVID interface from inception till February 2013: MEDLINE and EMBASE. The search combined terms for asthma, vitamin D, and pediatrics and included both free text words and medical subject heading. We did not use any search filter. The appendix provides the full details of the search strategies (see Additional file 1).

We used the following additional search strategies:

-

1.

Search of the grey literature: theses and dissertations;

-

2.

Search of the abstracts and proceedings from the following scientific meetings: American Thoracic Society (ATS), American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), Pediatric Academic Societies, European Respiratory Society, European Society for Pediatric Research, American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

-

3.

Review of references lists of included and relevant papers

-

4.

Forward searching of included papers (ISI Web of Science)

-

5.

Search of clinical trial registries

-

a.

ClinicalTrials.gov http://clinicaltrials.gov/

-

b.

International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) http://www.controlled-trials.com/isrctn/

-

c.

Register EU Clinical Trials Register (EU-CTR) https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu

-

d.

International Clinical Trial Registry Platform (ICTRP) http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/

-

a.

-

6.

Contact of authors of included studies inquiring about potentially eligible studies that we might have missed.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (LHA, MMF) screened in duplicate and independently the titles and abstracts of identified citations for potential eligibility. We obtained the full text for citations judged as potentially eligible by at least one of the 2 reviewers. The two reviewers then screened in duplicate and independently the full texts for eligibility. They used a standardized and pilot tested screening form and resolved disagreement by discussion. A senior team member (EAA) provided oversight.

Data collection

The two reviewers (LHA, MMF) abstracted in duplicate and independently data from eligible studies. They used a standardized and pilot-tested screening form and detailed written instructions. They resolved disagreement by discussion. A senior team member (EAA) provided oversight. We calculated the agreement between the two authors for the assessment of trial eligibility using kappa statistic.

The data abstracted included the type of study and funding, the characteristics of the population, intervention, control, and outcomes assessed and statistical data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The two reviewers assessed in duplicate and independently the risk of bias in each eligible study. They resolved disagreements by discussion or with the help of a third reviewer. According to recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook [13], we used the following criteria for assessing the risk of bias in randomized studies:

-

Inadequate sequence generation;

-

Inadequate allocation concealment;

-

Lack of blinding of participants, providers, data collectors, outcome adjudicators, and data analysts

-

Incompleteness of outcome data;

-

Selective outcome reporting, and other bias.

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear risk of bias.

Data analysis and synthesis

All studies reported their outcomes as continuous data. For each trial and for each outcome, we calculated the mean difference when all trials used the same scale and the standardized mean difference when trials used different scales. We pooled the results of trials using a random-effects model. We tested results for homogeneity across trials using the I2 test and consider heterogeneity substantial if I2 was greater than 50%. For the meta-analysis of vitamin D levels, we converted values reported in nmol/l by Schou et al. to ng/ml [14].

The number of studies was too small to create inverted funnel plots in order to check for possible publication bias. Similarly, we did not conduct planned subgroup or sensitivity analyses due to the limited number of included studies. We interpreted SMDs using the following rules suggested by the Cochrane Handbook [13]:<0.40 represents a small effect size; 0.40 to 0.70 represents a moderate effect size; >0.70 represents a large effect size.

We assessed the quality of evidence by outcome using the GRADE methodology [15]. We produced a GRADE Summary of Findings table to summarize the statistical findings and quality of evidence by outcome.

Results

Search results

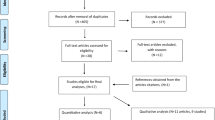

Figure 1 shows the study flow. The search strategy identified a total of 983 citations. Out of these, we assessed 274 full texts, of which we included 4 eligible studies [14,16-18]. The reasons for excluding the 270 full texts were as follows: 113 did not include original data, 96 did not answer our systematic review question, and 61 were observational studies. The agreement between the 2 reviewers for full text screening was high (kappa =0.94).We identified 12 ongoing trials assessing the effects of vitamin D in children with asthma symptoms (see Additional file 1 for more details).

Included studies

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included studies. We could not include data from Lewis et al [18] in the quantitative analyses because not all necessary statistics (e.g., standard deviation) were reported. The four studies were published in English between 2003 and 2012. All four studies were randomized. Three of the studies had a parallel study design [16-18], while the remaining study (Schou [14]) had a crossover design. The numbers of participants included in the studies were 17 [14], 30 [18], 48 [17], and 54 [16], with a total of 149 participants included in this systematic review.

Two studies were conducted in an allergy clinic in Poland [16,17], while the other two were conducted in an outpatient children clinic in Denmark [14] and in USA [18]. Two studies included only house dust mite sensitized asthma patients [16,17], while the other two included patients with chronic asthma on daily asthma medications [14,18]. Only two studies reported mean baseline serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D levels [16,17]. These levels were mostly within normal limits [21]. One study excluded patients with severe asthma (FEV1 < 70%) [16].

The dose and duration of vitamin D supplementation varied across the included studies as follows: six weeks with 600 IU/day [14], six months with 500 IU/day [17], twelve months with 1,000 IU/day [18], and nineteen months with 1000 IU/week [16].

Risk of bias in included studies

Table 2 summarizes the assessment of risk of bias in included studies. In terms of sequence generation, three reported adequate methods [14,16,17] while the fourth did not report on the method used. None of the studies reported on the method of allocation concealment. Three studies [14,16,17] reported using blinding, while the fourth study [18] did not. All studies reported number of participants with missing data; two had relatively high numbers of missing data: 11.7% in Schou et al. and 33.3% in Lewis et al. [14,18].

Effects of interventions

Asthma symptoms

Three studies reported statistical data about the effect of vitamin D on asthma symptoms, using different scales [14,16,17]. While one study used a validated score [17,20], the other two used respectively a diary card [16] and a score without any evidence of validation reported [14]. As we were uncertain whether these different instruments are actually measuring the same outcome, we opted not to pool the results. While all three studies reported improvement in asthma symptoms in the vitamin D supplemented group study, there was no statistically significant difference between this group and the comparison/placebo groups [14,16,17]. The fourth study by Lewis et al. reported that Vitamin D supplementation did not affect the asthma symptom score [18]. The associated level of quality of evidence was judged to be very low due to risk of bias, heterogeneity and imprecision (see Table 3).

FEV-1

Two of the included studies assessed post treatment FEV-1% predicted [16,17]. A meta-analysis resulted in a mean difference of 0.54% predicted, 95% CI (-5.28; 4.19) (See Figure 2). The level of heterogeneity was moderate (I2 54%). We did not include a third study assessed in the meta-analysis because it expressed the outcome as a mean FEV-1 level and we could not obtain the data as FEV-1% predicted from the author. That study found no clinically or statistically significant difference between the two arms (2.08 (SD 0.12) versus 2.10 (SD 0.12); p = 0.60) [14]. Lewis et al. reported that Vitamin D supplementation did not affect FEV-1 [18]. The associated level of quality of evidence was judged to be low due to risk of bias and imprecision (see Table 3).

Vitamin D levels

Three of the included studies reported the effect on vitamin D levels [13,15,16]. A meta-analysis resulted in a mean difference of 6.56 ng/ml, 95% CI (-0.64; 13.77) (See Figure 3). The level of heterogeneity was high (I2 97%). Lewis et al. reported that vitamin D levels in both groups increased significantly from baseline but did not differ significantly from each other at 6-month follow-up [17]. See Table 4 for reported details on Vitamin D dosage, supplementation duration used in each study, in addition to the interpretation of serum Vitamin D levels in each group of the included studies. The associated level of evidence was judged to be very low due to risk of bias, heterogeneity and imprecision (see Table 3).

Other outcomes

Only one study reported on the outcome of acute asthma exacerbations [17]. Over a follow up period of over six month, the percentage of children who experienced asthma exacerbation was significantly lower in the Vitamin D group (17% versus 46%, p = 0.029). This quality of evidence could be judged as low, at best, given the high risk of bias and the imprecision associated with the very small number of events. None of the identified studies reported on the effects on mortality and quality of life, and adverse effects associated with vitamin D.

Discussion

Our systematic review identified four randomized clinical trials assessing the effects of vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma. None of the identified studies reported on the effects on mortality, quality of life, or adverse effects associated with vitamin D supplementation. Meta-analysis neither confirmed nor ruled out beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation on lung function and vitamin D levels. The associated quality of evidence was rated as very low or low due to risk of bias, heterogeneity and imprecision.

The limitations of this review are related to those of the identified evidence. Not only studies were at high risk of bias, but also too small to provide precise results. In addition, their results were heterogeneous for asthma symptoms and vitamin D level outcomes. Due to the limited number of studies, we could not conduct subgroup analyses (e.g., based on pre-treatment level of Vitamin D) to attempt to explain this heterogeneity. None of the studies reported on vitamin D adverse effects. However, the doses used are generally considered to be safe and unlikely to be associated with adverse effects [22].

This systematic review has a number of strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review assessing the effects of vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma. We used standard systematic review methodology in literature searching, study selection, data abstraction, risk of bias assessment, and quality of evidence rating. Also, we have identified 12 ongoing trials, making future updates of this systematic review likely to provide precise and accurate estimates of both benefits and harms of vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma. Those might also allow us to explore whether any effect modifiers such as pre-treatment level of Vitamin D can explain any heterogeneity of results.

Conclusions

The major implication of our findings for clinical practice is that vitamin D cannot be considered for routine supplementation in children with asthma based on the currently available, at best, low quality evidence. Irrespectively, clinicians should consider vitamin D supplementation in children with low levels of vitamin D. However, our review does not address the question whether clinicians need to routinely test vitamin D levels in children with asthma.

Our findings have implications for future research. Future studies should be designed and executed in a way to minimize the risk of bias, and be reported clearly and comprehensively. Trials also need to be adequately powered to assess with precision the effects on the most important patient outcomes, including exacerbation, hospital admission, symptoms, quality of life, and adverse effects.

References

Eder W, Ege MJ, von Mutius E. The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(21):2226–35.

Flohr C. Recent perspectives on the global epidemiology of childhood eczema. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2011;39(3):174–82.

Bjorksten B, Clayton T, Ellwood P, Stewart A, Strachan D. Worldwide time trends for symptoms of rhinitis and conjunctivitis: phase III of the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(2):110–24.

Nurmatov U, Devereux G, Sheikh A. Nutrients and foods for the primary prevention of asthma and allergy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):724–33. e721-730.

Searing DA, Leung DY. Vitamin D in atopic dermatitis, asthma and allergic diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30(3):397–409.

Hossein-Nezhad A, Holick MF. Vitamin d for health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin Proceed Mayo Clin. 2013;88(7):720–55.

Gupta A, Sjoukes A, Richards D, Banya W, Hawrylowicz C, Bush A, et al. Relationship between serum vitamin D, disease severity, and airway remodeling in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(12):1342–9.

Sharief S, Jariwala S, Kumar J, Muntner P, Melamed ML. Vitamin D levels and food and environmental allergies in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1195–202.

Freishtat RJ, Iqbal SF, Pillai DK, Klein CJ, Ryan LM, Benton AS, et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among inner-city African American youth with asthma in Washington. DC J Pediatr. 2010;156(6):948–52.

Hypponen E, Sovio U, Wjst M, Patel S, Pekkanen J, Hartikainen AL, et al. Infant vitamin d supplementation and allergic conditions in adulthood: northern Finland birth cohort 1966. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1037:84–95.

Kull I, Bergstrom A, Melen E, Lilja G, van Hage M, Pershagen G, et al. Early-life supplementation of vitamins A and D, in water-soluble form or in peanut oil, and allergic diseases during childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(6):1299–304.

Mroueh S, Alkhaled L, Fares M, Akl E. Vitamin D for asthma in children. PROSPERO 2013:CRD42013004204 Available from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42013004204

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Schou AJ, Heuck C, Wolthers OD. Does vitamin D administered to children with asthma treated with inhaled glucocorticoids affect short-term growth or bone turnover? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36(5):399–404.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94.

Majak P, Rychlik B, Stelmach I. The effect of oral steroids with and without vitamin D3 on early efficacy of immunotherapy in asthmatic children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(12):1830–41.

Majak P, Olszowiec-Chlebna M, Smejda K, Stelmach I. Vitamin D supplementation in children may prevent asthma exacerbation triggered by acute respiratory infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1294–6.

Lewis E, Fernandez C, Nella A, Hopp R, Gallagher JC, Casale TB. Relationship of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and asthma control in children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108(4):281–2.

Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):59–65.

Skinner EA, Diette GB, Algatt-Bergstrom PJ, Nguyen TT, Clark RD, Markson LE, et al. The asthma therapy assessment questionnaire (ATAQ) for children and adolescents. Dis Manage DM. 2004;7(4):305–13.

Misra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A, Collett-Solberg PF, Kappy M. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):398–417.

Hathcock JN, Shao A, Vieth R, Heaney R. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):6–18.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Miss Aida Farha for her assistance with developing the search strategy, and Dr. Ghada El-Hajj Fleihan for her help in interpreting the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Concept and design: LHA, SMM, EAA. Study selection: LHA, MMF. Data collection: LHA, MMF. Data analysis: LHA, MMF, EAA. Data interpretation: LHA, MMF, GHF, SMM, EAA. Drafting of the manuscript: LHA, MMF, EAA, SMM. All authors reviewed and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Munes M Fares and Lina H Alkhaled are both considered as first authors.

Munes M Fares and Lina H Alkhaled contributed equally to this work.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Appendix 1- detailed search strategies. Appendix 2 - Ongoing clinical trials assessing the effects of vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Fares, M.M., Alkhaled, L.H., Mroueh, S.M. et al. Vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes 8, 23 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-014-0961-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-014-0961-3