Abstract

Background

Mass drug administration (MDA) with azithromycin is the primary strategy for global trachoma control efforts. Numerous studies have reported secondary effects of MDA with azithromycin, including reductions in childhood mortality, diarrhoeal disease and malaria. Most recently, the MORDOR clinical trial demonstrated that MDA led to an overall reduction in all-cause childhood mortality in targeted communities. There is however concern about the potential of increased antimicrobial resistance in treated communities. This study evaluated the impact of azithromycin MDA on the prevalence of gastrointestinal carriage of macrolide-resistant bacteria in communities within the MORDOR Malawi study, additionally profiling changes in the gut microbiome after treatment. For faecal metagenomics, 60 children were sampled prior to treatment and 122 children after four rounds of MDA, half receiving azithromycin and half placebo.

Results

The proportion of bacteria carrying macrolide resistance increased after azithromycin treatment. Diversity and global community structure of the gut was minimally impacted by treatment, however abundance of several species was altered by treatment. Notably, the putative human enteropathogen Escherichia albertii was more abundant after treatment.

Conclusions

MDA with azithromycin increased carriage of macrolide-resistant bacteria, but had limited impact on clinically relevant bacteria. However, increased abundance of enteropathogenic Escherichia species after treatment requires further, higher resolution investigation. Future studies should focus on the number of treatments and administration schedule to ensure clinical benefits continue to outweigh costs in antimicrobial resistance carriage.

Trial registration ClinicalTrial.gov, NCT02047981. Registered January 29th 2014, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02047981

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mass drug administration (MDA) with azithromycin has been the cornerstone of trachoma control programs since the 1990s and the advent of the SAFE strategy [1]. There has been considerable research since into the secondary effects of community-wide azithromycin distribution. A study from The Gambia was the first to report ancillary benefits [2]. They found all-cause illness, fever, diarrhoea and vomiting were reduced for at least 1-month post-treatment compared with topical tetracycline. Similarly, a study from Nepal found reductions in impetigo and diarrhoea up to 10 days post-treatment [3]. In 2009, Porco et al. reported a 50% reduction in all-cause mortality in children aged 1–9 years in Ethiopia in communities given azithromycin MDA [4]. This work has been expanded upon in studies across sub-Saharan Africa, demonstrating decreases in diarrhoea, malaria and all infectious mortality [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Alongside these benefits, there has been evidence of negative effects, primarily the emergence and increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance. A study of Aboriginal communities in Australia reported short-term reductions in the prevalence of nasopharyngeal Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage, but significant increases in macrolide-resistance in identified isolates [12]. Further studies have supported this increase in macrolide-resistant nasopharyngeal S. pneumoniae [3, 13, 14] as well as in faecal Escherichia coli [15,16,17], with evidence of macrolide and non-macrolide antimicrobial resistance in the latter.

Better defining the impact of azithromycin MDA on childhood morbidity and mortality was the aim of the MORDOR (Macrolides Oraux pour Réduire les Décès avec un Oeil sur la Résistance) clinical trial, which randomised 1533 communities across three sub-Saharan African countries to four biannual rounds of azithromycin treatment or placebo [18]. Azithromycin treatment led to an overall reduction in all-cause childhood mortality in targeted communities of 13.5% at 24-month follow-up, although the effect size varied between countries (Malawi; 5.7%, Niger; 18.1%, Tanzania, 3.4%). Secondary analyses found the impact of treatment to be most pronounced in the first 3 months post-treatment and in children aged 1–5 months [18, 19]. Despite Niger reporting the most significant effect on childhood mortality, there were no significant differences in the causes of mortality between the two study arms in this country [20]. In both the treatment and placebo arms, malaria (28%), pneumonia (16%) and diarrhoea (14–15%) accounted for the majority of verbal autopsy-confirmed deaths. All-cause mortality was reduced by 9% after treatment in Malawi, while this decrease was not significant, secondary analysis suggested pneumonia and diarrhoea or HIV/AIDS mortality were the drivers of this effect [21].

Findings from studies nested within MORDOR in Niger supported previous work that reported increases in antimicrobial resistance after azithromycin MDA. The proportion of macrolide-resistant nasopharyngeal S. pneumoniae isolated was four times greater after treatment [22]. Doan et al. further explored the impact of treatment on antimicrobial resistance and gut microbiome composition in Nigerien communities through metagenomics [23, 24]. They found increased prevalence of macrolide resistance after treatment, prevalence was approximately seven times greater after both four and eight bi-annual treatments. Additionally, after eight rounds of treatments, prevalence was also increased for other antimicrobial resistance classes, most prominently β-lactams. Treatment also had a long-term impact on the gut microbiome at 24-month follow-up, reducing diversity, as previously reported, and altering abundance of specific species [25, 26]. Notably, prevalence of the rarely identified human pathogen Campylobacter upsaliensis decreased after treatment. However, the majority of affected species have little known role in gut health or pathogenicity. In contrast, findings from a study nested within MORDOR in Malawi which profiled the gut microbiome by 16 S rRNA sequencing, found no change in diversity after treatment and limited impact on individual genera, with only a minor increase in Prevotella reported [27].

This study evaluated the impact of azithromycin MDA on the prevalence of gastrointestinal carriage of macrolide-resistant bacteria in communities within the MORDOR Malawi study site, where the observed reduction in childhood mortality after azithromycin treatment was considerably less than in Niger. Additionally, this study investigated changes in the gut microbiome after treatment.

Methods

Study design and participants

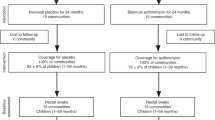

The study design has previously been described [28]. Briefly, the randomization unit for the MORDOR trial in Malawi was defined as the catchment area of a Health Surveillance Assistant (HSA), approximately 1000 total population. Communities with population < 200 or > 2000 on a pre-baseline census were excluded. Thirty communities were randomly selected for follow-up as part of studies of child morbidity and antimicrobial resistance (Fig. 1). The randomization was stratified to produce 6 communities in each of the 5 geographical zones of Mangochi District for geographical generalisability as well as for logistical reasons. Samples collected in the Makinjira zone were eligible for the current study of antimicrobial resistance determined by whole-genome-sequencing. Biannual census updates were performed, and communities received study drug in the same treatment rounds as the MORDOR mortality trial [18].

Trained local nursing staff explained the procedures and study and at the baseline, 12-month and 24-month follow-up visits, 40 children aged 1–59 months per community were randomly selected for stool sampling.

Intervention

All children aged 1–59 months and weighing ≥ 3.8 kg were eligible for treatment at each of 4 biannual mass distributions. Azithromycin was administered at a dose of 20 mg/kg. Children old enough to stand received an approximate dose estimated from their height and younger children were weighed. Distribution of the drug took place after sample collection was complete and was performed by the HSAs and fieldworkers conducting house-to-house visits. Guardians were asked to inform the HSA of any adverse events that occurred within 7 days of receiving study drug. HSAs subsequently informed the study team.

Sample collection

Sample collection took place during the baseline visit (May–July 2015) and at 12-month and 24-month visits (April–June 2016 and 2017 respectively), approximately 6 months after the second and fourth treatment rounds (Fig. 1). Parents or guardians who provided consent for sample collection were provided with a stool sample collection kit and were given instruction on how to collect the sample. Samples were returned to the field team immediately after collection and were held on wet ice until transport to the lab (within 8 h of collection). Once at the lab, samples were stored at − 80 °C until further processing.

Metagenomic sequencing

Bacterial DNA was extracted from 182 stool samples using the QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Kit (Qiagen) and eluted in EB Buffer. Concentration and purity of the extracts were assessed using a Nanodrop ND8000 (Thermo Scientific) and a subset of samples were processed on a Genomic Screentape using an Agilent 2200 Tapestation to assess integrity of the extracts. One hundred ng extracted DNA was used to generate whole genome libraries using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) alongside NEBNext® Multiplex Oligos for Illumina® (New England Biolabs). The average sizes of the resulting libraries were assessed using D1000 Screentapes on an Agilent 2200 Tapestation and concentrations were assessed using the Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit. The libraries were normalized to 4 nM and pooled into 4 pools of 37 libraries and 1 pool of 38 libraries. The average sizes of the pools were assessed using High Sensitivity D1000 Screentapes on an Agilent 2200 Tapestation and concentrations were assessed using the Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit. Each pool was subsequently sequenced on a NextSeq 500 using NextSeq® 500/550 High Output Kit v2 (Illumina) in a 150-cycle paired-end configuration.

Metagenomic analysis

Raw reads were filtered, trimmed and error-corrected using AfterQC [29]. Filtered reads were assembled into contigs using MEGAHIT [30]. Kraken [31] was used for taxonomic assignment of assembled contigs against complete bacterial, archaeal, and viral genomes from RefSeq [32], as of November 2017. ABRicate (https://github.com/tseeman/abricate) was used to screen assembled contigs for antimicrobial resistance genes against the ResFinder database, containing 2112 antimicrobial resistance genes from 14 antibiotic classes [33], a minimum sequence identity of 75% was used as a cut-off for calling hits [34]. Prevalence of macrolide resistance carriage was defined as at least one contig containing a macrolide-resistance allele for an individual. The proportion of bacteria carrying macrolide-resistance alleles was defined as the number of contigs containing a macrolide-resistance allele divided by the total number of contigs for an individual. Alpha diversity (Shannon’s H) and beta diversity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) were calculated using the R package vegan.

Outcome measures

Pre-specified primary outcome measures included the prevalence of carriage of macrolide resistance in the stool, at 24-month follow-up, as determined by genetic determinants. Secondary outcome measures included microbial diversity in the intestinal microbiome, at 24-month follow-up, as measured using next generation sequencing.

Statistical analysis

Alpha diversities were compared by linear regression, adjusting for age. Beta diversities were compared by PERMANOVA with 1000 permutations using the R package vegan. Species abundance profiles and proportion of bacteria carrying antimicrobial resistance genes were compared by zero-inflated negative binomial regression, adjusting for age. Time since last treatment analyses were further adjusted for number of treatments received. P-values were corrected for multiplicity of testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure [35].

Results

Participants

Thirty samples per treatment arm at baseline and 61 samples per treatment arm at 24-month follow-up were randomly selected for metagenomic sequencing (Fig. 1). Age and sex were comparable between treatment arms (Table 1). As expected, gut microbial diversity, based on Shannon’s H, increased with age (p = 0.237 × 10−9). Microbial composition, based on principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, changed significantly with age (PERMANOVA; p = 0.020). Sex did not significantly impact gut microbial diversity (p = 0.754) or composition (PERMANOVA p = 0.170). Additionally, at baseline, study arms were equivalent in gut microbial diversity (p = 0.596) and composition (PERMANOVA p = 0.829). All analyses were adjusted for age of participants and multiplicity of testing.

Antimicrobial resistance profile after treatment

The majority of individuals (180/182) carried at least one bacterium carrying macrolide resistance, with no difference by arm or time (Table 2). Bacteria most frequently carrying macrolide resistance were Enterococcus (E. cecorum and E. faecium), Bifidobacterium (B. breve, B. longum and B. kashiwanohense) and Streptococcus (species unknown). No changes in prevalence of carriage of macrolide resistance were found in individual species over time.

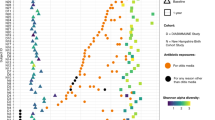

Due to the high baseline prevalence of carriage of bacteria with macrolide resistance, we compared the proportion of bacteria carrying macrolide resistance. The proportion of bacteria carrying macrolide resistance increased significantly after treatment (p = 0.827 × 10−7) (Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences in non-macrolide antimicrobial resistance after treatment, although an increase in prevalence of bacteria carrying aminoglycoside (p= 0.064) and trimethoprim (p = 0.059) resistance was close to significance (Fig. 2b). Carriage of macrolide resistance was not correlated with either aminoglycoside (Pearson’s r = −0.154) or trimethoprim resistance (r = −0.153), carriage of resistance to these two non-macrolide antibiotics was correlated (r = 0.849).

Antimicrobial resistance profile in children receiving either placebo or azithromycin treatment. a The proportion of macrolide-resistant bacteria at 24-month follow-up in children receiving either placebo (blue) or azithromycin (red). b Univariate analysis of antibiotic classes with increased evidence of resistance (linear regression coefficient > 0) or decreased evidence of resistance (linear regression coefficient < 0) after azithromycin treatment. Flat-headed lines indicate the standard error around the coefficient. c The proportion of macrolide-resistant bacteria during 24-month follow-up in children receiving azithromycin 6 months or 12–24 months previously. P-values were considered significant at < 0.05 and are denominated as follows: ***p < 0.001

Most studies on the impact of azithromycin treatment have focused on changes in the days or weeks post-treatment. We therefore examined the relationship between time since treatment and macrolide resistance carriage. 60% of individuals in the azithromycin arm received treatment 6-months before sample collection at 24-month follow-up (37/61), individuals whose last treatment occurred 12-, 18- or 24-months prior to follow-up sample collection were combined (24/61). All analyses were adjusted for number of treatments received. Greater than 0.3% of gut bacteria carrying macrolide-resistance alleles was more common in children treated 6-months prior to treatment (8/37; 21.6%) compared to 12–24-months prior (1/24, 4.2%), however there was no significant difference in carriage of macrolide-resistance alleles between these groups (Fig. 2c).

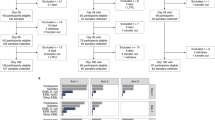

Changes in the gut microbiome after treatment

To further explore changes in the gastrointestinal flora, we determined the impact of treatment on gut microbiome composition. In the azithromycin arm, gut microbial diversity was unchanged after treatment (p = 0.454) (Fig. 3a). Treatment did not impact global gut microbial composition (PERMANOVA p = 0.598) (Fig. 3b). Univariate analyses identified thirty differentially abundant species after azithromycin treatment, fifteen reduced and fifteen increased (Fig. 3c, Additional file 1: Table S1). The greatest reductions were found in Lactobacillus crispatus, Klebsiella variicola, Desulfovibrio piger and the archaeon Methanosphaera stadtmanae. The largest increases were in Candidatus saccharibacteria and Escherichia albertii. Additionally, seven Acinetobacter species were increased after treatment, including A. baumanni, A. johnsonii, A. pitii and A. soli.

Gut microbial diversity, composition and specific bacteria in children receiving either placebo or azithromycin treatment. a Alpha diversity, determined by Shannon’s H, at 24-month follow-up in children receiving either placebo (blue) or azithromycin (red). b Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between children by treatment arm. Axes labels indicate the plotted component and percentage variance explained. c Univariate analysis of bacterial species with increased abundance (linear regression coefficient > 0) or decreased abundance (linear regression coefficient < 0) after azithromycin treatment

We additionally examined the relationship between time since treatment and changes in the gut microbiome. Alpha diversity was not different between those treated 6-months prior or 12–24-months prior to sample collection (p = 0.114). Beta diversity showed clustering of individuals treated 6-months prior (Fig. 4a), although this did not reach significance (p = 0.056). This was supported by significantly reduced abundance of thirteen bacterial species in those treated 6-months prior compared to those treated 12–24-months prior (Fig. 4b, Additional file 1: Table S2), including Klebsiella pneumoniae (p = 0.0002) and Haemophilus influenzae (p = 0.0003).

Gut microbial composition and antibiotic-resistance profile in children who received azithromycin 6-months or 12–24-months previously. a Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between children by time since last azithromycin treatment (12–24 months = green, 6 months = orange). Axes labels indicate the plotted component and percentage variance explained. b Univariate analysis of antibiotic classes with increased evidence of resistance (linear regression coefficient > 0) or decreased evidence of resistance (linear regression coefficient < 0) in children who received azithromycin 6 months previously compared to 1–24 months previously

To determine the impact of treatment on known causes of diarrhoea, we further investigated differences in abundance of pathogenic bacteria identified by the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries [36]. No genera or species was significantly different in children who received treatment (Table 3) although there was a trend towards increased abundance in treated children for 4/5 pathogens. One of the pathogenic bacteria, Vibrio cholerae, was not identified in this study. Combined abundance of pathogenic bacteria was also not significantly different in children who received treatment, although the trend was again towards increased abundance in treated children.

Discussion

This study utilised metagenomic sequencing to examine the impact of azithromycin treatment on carriage of macrolide-resistance bacteria in the gut. Additionally, this study investigated changes in the gut microbiome after treatment. There was significant evidence for increased macrolide resistance after treatment. Gut microbial diversity and global community composition was not impacted by treatment, in agreement with 16S rRNA profiling of a separate longitudinal cohort of children enrolled within MORDOR in Malawi. However, individual species were differentially abundant after treatment, including the putative human enteropathogen Escherichia albertii.

Macrolide resistance increased after four biannual rounds of azithromycin treatment. Individuals with the highest proportion of bacteria carrying macrolide resistance had mostly been treated 6-months prior to sampling as opposed to 12–24-month prior, however there was no significant impact of time-since treatment on macrolide resistance. A study of children aged < 5 years in rural Tanzania surveyed macrolide resistance in faecal E. coli following community-wide distribution of azithromycin for trachoma control found that post-treatment increase in macrolide resistance waned over time [16]. The proportion of macrolide-resistant isolates increased sharply in the first month following MDA (16.3% to 61.2%) but had declined significantly by 6 months (31.3%). Studies of perturbation of the gut microbiome following azithromycin treatment consistently find detectable changes within a few days and these can last up to 6 months [37, 38], however, longer-lasting impact varies between studies [39, 40]. Future work should ideally include sampling within days of treatment and follow-up beyond 2 years to determine the immediate and enduring impact of azithromycin on faecal carriage and emergence of macrolide resistance.

Prevalence of carriage of at least one macrolide resistant bacterium was higher in this study conducted in Malawian villages compared to those from Niger. At baseline in Niger, the majority of villages had no evidence of macrolide resistance, assessed by metagenomics, in either arm [23]. By contrast, 58/60 individuals (across both arms) sampled at baseline in Malawi had evidence of macrolide resistance. There is preliminary data from Tanzania suggesting availability of azithromycin at local pharmacies can impact community-level prevalence of antimicrobial resistance [41]. These Tanzanian communities had received 4 consecutive years of MDA and were revisited 4 years after cessation. At this time, there was a trend towards increased prevalence of macrolide-resistant faecal E. coli and nasopharyngeal S. pneumoniae in hamlets where azithromycin was locally available. Despite the differences in baseline prevalence of carriage of macrolide resistant bacteria, the impact of treatment was relatively consistent between Malawi and Niger. Both reported a small reduction in gut microbial diversity after treatment and increased evidence of macrolide resistance, although the latter was determined at the village-level rather than individual-level. However, it is possible that higher baseline levels of resistance to macrolides in Malawi were a factor in the significantly reduced impact of treatment on childhood mortality compared with Niger. This hypothesis could be further evaluated by determining pre-treatment prevalence of macrolide resistance in the Tanzanian communities enrolled in MORDOR, where the lowest impact of treatment was reported [18] and assessment of antibiotic availability in rural Malawi.

In agreement with findings from Niger, we detected no significant changes in prevalence of resistance to non-macrolide antibiotics after four rounds of treatment [23]. However, after a further two rounds of treatment in Nigerien communities [24], resistance to several classes of non-macrolide antibiotics was increased, this was maintained after two additional treatment rounds for β-lactams. Prevalence of resistance to aminoglycosides and trimethoprim was significantly greater after six rounds of treatment in Niger; resistance to these two antibiotic classes was non-significantly increased after four rounds of treatment in our study. The most common explanation for this effect is multi-drug resistant bacteria, driven by shared mechanisms of resistance or genetic linkage, however, carriage of aminoglycoside and trimethoprim resistance was independent of macrolide resistance in this study. It is possible that increases in off-target antibiotic resistance in the gut microbiome of children from studied Malawian communities would reach significance with further rounds of treatment, as reported in Niger.

Five of six bacteria highlighted as common causes of diarrheal disease by the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of infants and young children in developing countries were detectable in this study [36]. While none were significantly impacted by treatment, combined abundance of these diarrhoeal pathogens was higher after treatment, although this did not reach significance. Focusing on pathogenic E. coli strains demonstrated a significant increase in abundance of enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) after treatment. Strain-level results should be treated with caution as the majority of reads were not classifiable beyond species-level. A similar increase was observed in Escherichia albertii, a close relative of E. coli [42]. Recent data suggests many gastrointestinal infections classified as E. coli infections may be the related E. albertii [43, 44]. E. albertii possesses many of the virulence factors found in EPEC and multi-drug resistant isolates have been recovered from clinical samples [45, 46]. Importantly, there was no evidence of macrolide resistance in EPEC or E. albertii sequences at 24-month follow-up in either arm of the study; it is likely that abundance of this pathogen increased as an effect of treatment rather than it being resistant. For example, it is possible that higher azithromycin susceptibility of other pathogens such as Campylobacter, Salmonella and Shigella may indirectly lead to increased abundance of EPEC and E. albertii [47]. Targeted higher-resolution sequencing of Escherichia to accurately differentiate species and identify strains of E. coli would be of value.

In this study, the abundance of several Acinetobacter species increased after treatment, which can be partly explained by their intrinsic resistance to macrolides [48]. Despite this, the prevalence of the opportunistic pathogens A. baumanni, A. johnsonii, A. pitii and A. soli is concerning. A. baumanni infections are often hospital-acquired with the majority of community-acquired infections presenting in individuals with underlying health conditions [49, 50]. High mortality rates and rapid emergence of antimicrobial resistance suggest this species requires consideration as a serious human pathogen. This was highlighted in this study by evidence of two macrolide-efflux genes (mphE and msrE) in an A. baumanni isolate from a child in the azithromycin treatment arm. Further studies are required to elucidate the impact of these species and whether detection in the gut has any clinical relevance.

The findings presented here are limited to a single geographical zone in the Mangochi district of Malawi, which may limit extrapolation to wider populations. Further to this, participation in faecal sampling was incomplete as approximately 70% of enrolled children provided samples. Given the observed individual-level heterogeneity in this study, it is possible more complete sampling of enrolled children would have led to different outcomes. However, the overlap with results from Niger suggest these effects may be consistent across study sites. Additionally, very few of the individuals sampled herein were aged 1–5 months, the group which saw the greatest reduction in mortality after treatment. It is possible that treatment may have a different impact on the gut microbiome in these younger children.

Conclusions

In summary, this study found significant changes in the antimicrobial resistance profile and gut microbiome after four biannual rounds of azithromycin. Carriage of macrolide resistance was increased by treatment. Abundance of the putative human enteropathogen E. albertii was increased after treatment, as well as several opportunistic Acinetobacter pathogens. Given that multiple treatments enhanced the beneficial effects of azithromycin treatment, consideration should be given to the number of treatments and administration schedule to ensure benefits continue to outweigh costs in antimicrobial resistance.

Availability of data and materials

All sequence data are available from the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) short read archive (PRJEB42363).

Abbreviations

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EPEC:

-

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli

- GEMS:

-

Global Enteric Multicenter Study

- HSA:

-

Health surveillance assistant

- MDA:

-

Mass drug administration

- MORDOR:

-

Macrolides Oraux pour Réduire les Décès avec un Oeil sur la Résistance

- PC:

-

Principal component

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- SAFE:

-

Surgery for entropion/trichiasis; antibiotics for infectious trachoma; facial cleanliness to reduce transmission; environmental improvements such as control of disease-spreading flies and access to clean water

References

Emerson PM, Burton M, Solomon AW, Bailey R, Mabey D. The SAFE strategy for trachoma control: using operational research for policy, planning and implementation. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:613–9.

Whitty CJM, Glasgow KW, Sadiq ST, Mabey DC, Bailey R. Impact of community-based mass treatment for trachoma with oral azithromycin on general morbidity in Gambian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:955–8.

Fry AM, Jha HC, Lietman TM, Chaudhary JSP, Bhatta RC, Elliott J, et al. Adverse and beneficial secondary effects of mass treatment with azithromycin to eliminate blindness due to trachoma in Nepal. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:395–402.

Porco TC, Gebre T, Ayele B, House J, Keenan J, Zhou Z, et al. Effect of mass distribution of azithromycin for trachoma control on overall mortality in Ethiopian children: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302:962–8.

Coles CL, Seidman JC, Levens J, Mkocha H, Munoz B, West S. Association of mass treatment with azithromycin in trachoma-endemic communities with short-term reduced risk of diarrhea in young children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:691–6.

Keenan JD, Ayele B, Gebre T, Zerihun M, Zhou Z, House JI, et al. Childhood mortality in a cohort treated with mass azithromycin for trachoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:883–8.

Schachterle SE, Mtove G, Levens JP, Clemens E, Shi L, Raj A, et al. Single dose mass drug administration of azithromycin decreases malaria incidence in a large cohort treated for ocular trachoma. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(6 SUPPL. 1):276–7.

Schachterle SE, Mtove G, Levens JP, Clemens E, Shi L, Raj A, et al. Short-term malaria reduction by single-dose azithromycin during mass drug administration for trachoma, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:941–9.

Gaynor BD, Holbrook KA, Whitcher JP, Holm SO, Jha HC, Chaudhary JSP, et al. Community treatment with azithromycin for trachoma is not associated with antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae at 1 year. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:147–8.

See CW, O’Brien KS, Keenan JD, Stoller NE, Gaynor BD, Porco TC, et al. The effect of mass azithromycin distribution on childhood mortality: beliefs and estimates of efficacy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:1106–9.

Arzika AM, Maliki R, Boubacar N, Kane S, Cotter SY, Lebas E, et al. Biannual mass azithromycin distributions and malaria parasitemia in pre-school children in Niger: a cluster-randomized, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002835.

Leach AJ, Shelby-James TM, Mayo M, Gratten M, Laming AC, Currie BJ, et al. A prospective study of the impact of community-based azithromycin treatment of trachoma on carriage and resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:356–62.

Skalet AH, Cevallos V, Ayele B, Gebre T, Zhou Z, Jorgensen JH, et al. Antibiotic selection pressure and macrolide resistance in Nasopharyngeal Streptococcus pneumoniae: a cluster-randomized clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000377.

Burr SE, Milne S, Jafali J, Bojang E, Rajasekhar M, Hart J, et al. Mass administration of azithromycin and Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage: cross-sectional surveys in the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:490–8.

Seidman JC, Coles CL, Levens J, Mkocha H, Munoz B, West SK. Increased resistance to azithromycin in E. coli following mass treatment for trachoma control in rural Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:178.

Seidman JC, Coles CL, Silbergeld EK, Levens J, Mkocha H, Johnson LB, et al. Increased carriage of macrolide-resistant fecal E. coli following mass distribution of azithromycin for trachoma control. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(4):1105–13.

Seidman JC, Johnson LB, Levens J, Mkocha H, Muñoz B, Silbergeld EK, et al. Longitudinal comparison of antibiotic resistance in diarrheagenic and non-pathogenic Escherichia coli from young Tanzanian children. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1420.

Keenan JD, Bailey RL, West SK, Arzika AM, Hart J, Weaver J, et al. Azithromycin to reduce childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1583–92.

Porco TC, Hart J, Arzika AM, Weaver J, Kalua K, Mrango Z, et al. Mass oral azithromycin for childhood mortality: timing of death after distribution in the MORDOR trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:2114–6.

Keenan JD, Arzika AM, Maliki R, Elh Adamou S, Ibrahim F, Kiemago M, et al. Cause-specific mortality of children younger than 5 years in communities receiving biannual mass azithromycin treatment in Niger: verbal autopsy results from a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e288–95.

Hart JD, Kalua K, Keenan JD, Lietman TM, Bailey RL. Effect of mass treatment with azithromycin on causes of death in children in Malawi: secondary analysis from the MORDOR trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:1319–28.

Doan T, Arzika AM, Hinterwirth A, Maliki R, Zhong L, Cummings S, et al. Macrolide resistance in Mordor I—a cluster-randomized trial in Niger. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2271–3.

Doan T, Hinterwirth A, Worden L, Arzika AM, Maliki R, Abdou A, et al. Gut microbiome alteration in MORDOR I: a community-randomized trial of mass azithromycin distribution. Nat Med. 2019;25:1370–6.

Doan T, Worden L, Hinterwirth A, Arzika AM, Maliki R, Abdou A, et al. Macrolide and nonmacrolide resistance with mass azithromycin distribution. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1941–50.

Doan T, Arzika AM, Ray KJ, Cotter SY, Kim J, Maliki R, et al. Gut microbial diversity in antibiotic-Naive children after systemic antibiotic exposure: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1147–53.

Doan T, Hinterwirth A, Arzika AM, Cotter SY, Ray KJ, O’Brien KS, et al. Mass azithromycin distribution and community microbiome: a cluster-randomized trial. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofy182.

Chaima D, Pickering H, Hart JD, Burr SE, Houghton J, Maleta K, et al. Up to four biannual administrations of mass azithromycin treatment are associated with modest changes in the gut microbiota of rural Malawian children. 2020. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202010.0138.v1

Hart JD, Samikwa L, Sikina F, Kalua K, Keenan JD, Lietman TM, et al. Effects of biannual azithromycin mass drug administration on malaria in Malawian children: a cluster-randomized trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3):1329.

Chen S, Huang T, Zhou Y, Han Y, Xu M, Gu J. AfterQC: automatic filtering, trimming, error removing and quality control for fastq data. BMC Bioinform. 2017;18(Suppl 3):80.

Li D, Luo R, Liu CM, Leung CM, Ting HF, Sadakane K, et al. MEGAHIT v1.0: a fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods. 2016;102:3–11.

Wood DE, Salzberg SL, Kraken. Ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R46.

Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D61–5.

Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2640–4.

Doyle RM, O’Sullivan DM, Aller SD, Bruchmann S, Clark T, Coello Pelegrin A, et al. Discordant bioinformatic predictions of antimicrobial resistance from whole-genome sequencing data of bacterial isolates: an inter-laboratory study. Microb Genom. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000335.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300.

Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case–control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–22.

Parker EPK, Praharaj I, John J, Kaliappan SP, Kampmann B, Kang G, et al. Changes in the intestinal microbiota following the administration of azithromycin in a randomised placebo-controlled trial among infants in south India. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–9.

Abeles SR, Jones MB, Santiago-Rodriguez TM, Ly M, Klitgord N, Yooseph S, et al. Microbial diversity in individuals and their household contacts following typical antibiotic courses. Microbiome. 2016;4:39.

Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, Kekkonen RA, Forslund K, Bork P, et al. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–8.

Wei S, Mortensen MS, Stokholm J, Brejnrod AD, Thorsen J, Rasmussen MA, et al. Short- and long-term impacts of azithromycin treatment on the gut microbiota in children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. EBioMedicine. 2018;38:265–72.

Ansah D, Weaver J, Munoz B, Bloch EM, Coles CL, Lietman T, et al. A cross-sectional study of the availability of azithromycin in local pharmacies and associated antibiotic resistance in communities in Kilosa district, Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100:1105–9.

Ooka T, Ogura Y, Katsura K, Seto K, Kobayashi H, Kawano K, et al. Defining the genome features of Escherichia albertii, an emerging enteropathogen closely related to Escherichia coli. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:3170–9.

Ooka T, Seto K, Kawano K, Kobayashi H, Etoh Y, Ichihara S, et al. Clinical significance of Escherichia albertii. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:488–92.

Ooka T, Tokuoka E, Furukawa M, Nagamura T, Ogura Y, Arisawa K, et al. Human gastroenteritis outbreak associated with Escherichia albertii, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:144–6.

Bhatt S, Egan M, Critelli B, Kouse A, Kalman D, Upreti C. The evasive enemy: insights into the virulence and epidemiology of the emerging attaching and effacing pathogen Escherichia albertii. Infect Immun. 2019;87:e00254-18.

Li Q, Wang H, Xu Y, Bai X, Wang J, Zhang Z, et al. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia albertii: co-occurrence of β-lactamase and MCR-1 encoding genes. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:258.

Gordillo ME, Singh KV, Murray BE. In vitro activity of azithromycin against bacterial enteric pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1203–5.

Poirel L, Bonnin RA, Nordmann P. Genetic basis of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic Acinetobacter species. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:1061–77.

Taitt CR, Leski TA, Stockelman MG, Craft DW, Zurawski DV, Kirkup BC, et al. Antimicrobial resistance determinants in acinetobacter baumannii isolates taken from military treatment facilities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:767–81.

Morris FC, Dexter C, Kostoulias X, Uddin MI, Peleg AY. The mechanisms of disease caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1601.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of field staff at Blantyre Institute of Community Outreach and laboratory staff at College of Medicine, Blantyre, Malawi.

Funding

This work was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation under grant numbers OPP1066930 and OP1032340.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JDH, SB, KM, KK, RLB and MJH contributed to study design. JDH, SB, KM, KK and RLB contributed to data collection. HP, SB, RS and MJH contributed to data analysis. All authors interpreted the findings, contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the MORDOR trials in Malawi was obtained from the College of Medicine, University of Malawi (Malawi) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK). Written, informed consent was obtained from the guardians of participants of all participating children. Illiterate guardians provided a thumb print to acknowledge consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Results for zero-inflated negative binomial regression of species abundance on treatment received (Table S1) and time since treatment (Table S2).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pickering, H., Hart, J.D., Burr, S. et al. Impact of azithromycin mass drug administration on the antibiotic-resistant gut microbiome in children: a randomized, controlled trial. Gut Pathog 14, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-021-00478-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-021-00478-6