Abstract

Background

The serum creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio (Scr/Scys) has been suggested as a surrogate marker of muscle mass and a predictor of adverse outcomes in many diseases. However, the prognostic value of Scr/Scys in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is unknown. The aim of this study is to assess the prognostic value of Scr/Scys in patients with T2DM.

Methods

In this retrospective observational study, we enrolled 3668 T2DM patients undergoing coronary angiography (CAG). Serum creatinine (Scr) and serum cystatin C (Scys) levels were measured at admission. The study population was separated into low muscle mass (low-MM) and normal muscle mass (normal-MM) groups by Scr/Scys cut-off point. The association between muscle mass and long-term all-cause mortality was examined using Cox regression analysis.

Results

During a median follow-up of 4.9 (3.0–7.1) years, a total of 352 (9.6%) patients died. The mortality was higher in patients with low-MM as compared with patients with normal-MM (11.1% vs. 7.3%; p < 0.001). Low muscle mass was associated with increased risk for long-term all-cause mortality, regardless of whether Scr/Scys were used as a continuous variable (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.08 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 to 1.13]; p = 0.009) or a categorial variable (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.36 [95% CI 1.03 to 1.75]; p = 0.021).

Conclusion

Low muscle mass assessed by Scr/Scys was associated with increased risk of long-term all-cause mortality in diabetic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sarcopenia is age-related degenerative skeletal disease characterized by a progressive and generalized reduction in muscular mass, strength, and function [1]. The prevalence of sarcopenia is significantly higher in diabetics than in non-diabetics [2]. In diabetics, sarcopenia is associated with poor outcomes, such as albuminuria, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), atherosclerosis, cognitive impairment, infection and mortality [3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

The presence of low muscle mass (low-MM) is the core component of the algorithm to diagnose sarcopenia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) are used to measure the quantity of muscle mass [1]. However, these methods require specific devices and have limitations such as exposure to radiation and lack of cost-effectiveness [10]. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) is a cost-effective measurement of muscle mass but is adversely influenced by the volume status of patients [11]. Recently, the serum creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio (Scr/Scys), also known as the sarcopenia index (SI), is suggested as a surrogate marker of muscle mass in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cancer [12,13,14]. Furthermore, Scr/Scys is also a predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury (AKI), coronary artery disease (CAD), acute ischemic stroke, COPD and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [13, 15,16,17,18]. However, the relationship between Scr/Scys and clinical outcome in diabetic patients is unclear.

Therefore, we aim to evaluate the prognostic value of Scr/Scys for long-term mortality risk in patients with T2DM.

Methods

Study population

The present study was a retrospective observational cohort study, using data from the Cardiorenal ImprovemeNt (CIN) study which was conducted in the largest cardiovascular centre in South China (Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, China, Clinicaltrials.gov NCT04407936). A total of 88,938 patients underwent coronary angiography (CAG) from January 2007 to December 2018, and 25,027 patients were over 18 years old and diagnosed as T2DM. We excluded patients with CKD and cancer (n = 9,655), missing measurement of serum creatinine (Scr) and serum cystatin C (Scys) (n = 11,170) and follow-up information (n = 534). Eventually, 3668 patients were included (Fig. 1). The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital ethics committee.

Data collection

Data were extracted from the electronic clinical management records system of the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. The baseline information mainly included demographic characteristics, medical history, medications at discharge, laboratory test results and other clinical variables. Venous blood samples were collected in the early morning after overnight fasting.

Scr and Scys measurement and clinical definition

Scr and Scys levels were measured at admission before coronary angiography, and blood tests were conducted as routine practice by a laboratory center in Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital.

The Scr/Scys, a surrogate marker of muscle mass, was calculated as [Scr (mg/dL)/ Scys (mg/L)]. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) value was calculated based on Scr level using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) 2009 equation, and CKD was defined as eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a medical history of CKD. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Smoking was defined as smoking at least one cigarette a day for more than one year. Alcohol drinking was defined as drinking an average of two or more times per week for more than one year.

Endpoint and follow-up

The primary endpoint was long-term all-cause mortality. All-cause death information was obtained from the Public Security and matched to the electronic Clinical Management System of the Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital records.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (inter-quartile range) according to the distribution of the continuous variable, and as frequencies or percentages for categorical variables. For comparisons between groups, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, and an unpaired Student's t test was used for continuous variables, as appropriate.

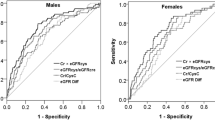

The optimal cut-off values for Scr/Scys were determined by time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis according to gender. Using the cut-off values, we separated the study population into low muscle mass (low-MM) and normal muscle mass (normal-MM) groups. The time to endpoint data were presented graphically using Kaplan–Meier (K-M) curves, and a log-rank test was used to compare differences between the groups. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the relationship between muscle mass and long-term all-cause mortality. Variables that were entered into the model were carefully selected based on variables associated with known poor prognosis or variables with p-value < 0.05 in baseline or in univariable regression analysis. We also performed a subgroup analysis to assess the impact of muscle mass on long-term all-cause mortality.

Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.0.3 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 3668 consecutive T2DM patients undergoing CAG were enrolled. Most patients were men (67.7%), and the mean age was 62.4 ± 9.9 years. Totally, 2883 (78.6%) patients were diagnosed as CAD, and 326 (8.9%) patients had congestive heart failure (CHF). There were 2206 (60.1%) patients with hypertension, 210 (5.7%) patients with stroke, 1026 (28.0%) patients with anemia, and 22 (0.6%) patients with COPD. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was 7.62% ± 1.60. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was 9.28 ± 4.37 mmol/L, 2 h postprandial blood glucose (2hPBG) was 12.06 ± 4.51 mmol/L (Additional file 1: Table S1).

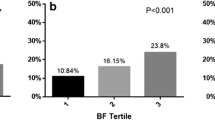

Prevalence and clinical associations of low muscle mass

A median follow-up of 5 years was selected as the predict time in the time-dependent ROC analysis. The cut-off values of Scr/Scys for the best predictive value of mortality were 1.0 for men and 0.8 for women (Additional file 3: Fig. S1). According to the cut-off values, the study population were separated into low-MM and normal-MM groups. Of the 3668 participants, 2191 (59.7%) had low muscle mass. Compared with patients with normal muscle mass, patients with low muscle mass were older (63.8 ± 9.8 vs. 60.3 ± 9.7 years, p < 0.001), and had higher FBG (9.74 ± 4.61 vs. 8.99 ± 4.18 mmol/L, p < 0.001) and 2 h PBG levels (12.51 ± 4.65 vs. 11.83 ± 4.43 mmol/L, p = 0.009). Patients with low muscle mass also had lower triglyceride (TG) [1.44(1.07, 2.04) vs. 1.51(1.10, 2.16) mmol/L, p = 0.004], high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (0.96 ± 0.24 vs. 0.98 ± 0.25 mmol/L, p = 0.011) and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (2.75±0.94 vs. 2.81 ± 0.95 mmol/L, p = 0.047) levels. The incidences of smoking, anemia and COPD in patients with low muscle mass were higher than those with normal muscle mass (39.1 vs. 35.8%, p = 0.043; 0.9 vs. 0.2%, p = 0.019; 29.7 vs. 25.4%, p = 0.005, respectively). More data on the baseline characteristics of study population are shown in Table 1.

Low muscle mass and clinical outcomes

During a median follow-up of 4.9 (3.0–7.1) years, a total of 352 (9.6%) patients died from all causes. The long-term all-cause mortality was higher in patients with low muscle mass as compared with patients with normal muscle mass (11.1% vs. 7.3%; p < 0.001). The time-to-event curves of long-term all-cause mortality are displayed in Fig. 2.

Multivariable analysis indicated that low muscle mass was associated with significantly increased risk for long-term all-cause mortality, regardless of whether Scr/Scys was used as a continuous variable (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.08 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 to 1.13]; p = 0.009) or a categorial variable (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.36 [95% CI 1.03 to 1.75]; p = 0.021) (Table 2). Univariable analysis was shown in Additional file 2: Table S2, while subgroup analysis was shown in Additional file 4: Fig. S2.

Discussion

In this cohort study of T2DM patients who underwent CAG, we found that low muscle mass evaluated by Scr/Scys was independently associated with long-term all-cause mortality. Patients with low muscle mass had a 36% higher risk for mortality than patients with normal muscle mass. Scr/Scys has the clinical prognostic value for long-term all-cause mortality in T2DM patients undergoing CAG.

Sarcopenia has been recognized as a disease by the World Health Organization (WHO)’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) since 2016 [19]. The prevalence of sarcopenia defined according to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) criteria was estimated to be approximately 7–20% in diabetic patients, with a variation in prevalence across healthcare settings [20,21,22,23]. The prevalence of sarcopenia using the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) criteria was 15.9% in Asian diabetics [2]. The presence of low muscle mass constitutes the most critical step in the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Creatinine is an endogenous product released from muscles, and its blood concentration is dependent on muscle mass but is affected by kidney function [24]. Cystatin C is secreted by all nucleated cells, and its production and tubular secretion are uniform and not affected by muscle mass. Cystatin C is a measure of renal function and has been shown to predict glomerular filtration rate better than creatinine-based estimates [25]. Recently, Scr/Scys has been considered as a quantitative surrogate marker of muscle mass in many diseases [12,13,14].

There was evidence to indicate worsening of clinical outcomes when diabetes was associated with low muscle mass. A cohort study included 163 Japanese men and 141 postmenopausal women with T2DM showed that low muscle mass measured by DEXA was independently associated with all-cause mortality in female patients with T2DM [9]. On the contrary, Kruse NT et al. found that low muscle mass measured by BIA was independently associated with higher mortality in men, while neither definition of sarcopenia was associated with mortality in men or women with CKD [26]. Our large sample retrospective study, including 3668 T2DM population, showed that low muscle mass assessed by a simple indicator Scr/Scys, was independently correlated with long-term all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease or at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Our study also found that the effect of low muscle mass on outcome was statistically significant in the male subgroup and not in the female subgroup, but the interaction effect between low muscle mass and gender was not found. Therefore, further prospective studies are needed to explore this question.

The possible explanation for the association of Scr/Scys with mortality could be as follows. The muscle mass may reflect nutritional status, and definitions of malnutrition include low muscle mass within its diagnostic criteria [27,28,29]. Previous studies showed that malnutrition was correlated with increased mortality and cardiovascular events of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), heart failure and diabetes [30,31,32,33]. Moreover, higher cystatin C levels have been observed in patients with chronic inflammation. Therefore, lower Scr/Scys levels may be associated with inflammation [34]. Sarcopenia is known to be associated with inflammation. Inflammation is known to be predictor of increased mortality and cardiovascular events [35, 36].

As a noninvasive, easily measured and cost-effective biomarker of muscle mass and a useful prognosticator for patients with T2DM, Scr/Scys may be useful in various aspects of future clinical practice. The application of Scr/Scys to routine practice may help physicians identify patients at high risk of poor outcomes who might benefit from supplementation of protein and vitamin D and physically active lifestyles [37,38,39]. In addition, some hypoglycemic agents such as sulfonylureas and glinides have adverse effects on skeletal muscle, suggesting the need to circumvent the use of these drugs in diabetes patients with sarcopenia. Glucagon-like peptide 1(GLP-1) receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase 4(DPP4) inhibitors seem to be favorable in protecting muscles. Although insulin can also increase muscle mass in patients with T2DM, the weight gain effect of insulin cannot be ignored, which should be carefully considered in the treatment of T2DM patients [40].

Our study has several limitations. First, our results were subject to limitations of the observational nature inherent in the retrospectively collected database. Second, we did not compare the prognostic value of Scr/Scys with DEXA, BIA, CT or MRI. However, we aimed to focus more on the prognostic value of the easily measured marker and to derive results that could be helpful in actual clinical practice. Third, since patients with missing measurement of Scr and Scys excluded, there is a possibility of selection bias. The percentage of patients with normal muscle mass was low in the present analysis can be partly explained by the bias. Fourth, we did not evaluate the relationship of Scr/Scys with inflammatory markers, and we did not investigate the changes in muscle mass over time and their association with mortality outcomes. This will require further validations in future studies. Fifth, the patients included in our study were diabetic patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or at high risk of cardiovascular disease, so the results of our study could not be extended to the general diabetic patients. The prognostic value of Scr/Scys in the general diabetic patients needs to be verified in the further research. Finally, long-term all-cause mortality was complex and multivariable. Due to the lack of other endpoint events, this will limit to generalize our results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, low muscle mass evaluated by Scr/Scys was associated with increased risk of long-term all-cause mortality in diabetic patients. The application of such a readily available indicator may help clinicians to identify diabetic patients at elevated risk for mortality and to prevent poor outcome.

Availability of data and materials

Data relevant to this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- ACEI/ARB:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker

- AWGS:

-

Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BIA:

-

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CAG:

-

Coronary angiography

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CCB:

-

Calcium channel blocker

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CIN:

-

Cardiorenal ImprovemeNt

- CKD-EPI:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- DR:

-

Diabetic retinopathy

- DPN:

-

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy

- DEXA:

-

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

- DPP4:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtrationrate

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- FNIH:

-

Foundation for the National Institutes of Health

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ICD:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- low-MM:

-

Low muscle mass

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- normal-MM:

-

Normal muscle mass

- OADs:

-

Oral antidiabetic drugs

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- Scr/Scys:

-

Serum creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio

- Scr:

-

Serum creatinine

- Scys:

-

Serum cystatin C

- SI:

-

Sarcopenia index

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- 2 h PBG:

-

2 Hours postprandial blood glucose

References

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169.

Chung SM, Moon JS, Chang MC. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its association with diabetes: a meta-analysis of community-dwelling asian population. Front Med. 2021;8: 681232. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.681232.

Low S, Pek S, Moh A, et al. Low muscle mass is associated with progression of chronic kidney disease and albuminuria—an 8-year longitudinal study in asians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;174: 108777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108777.

Fukuda T, Bouchi R, Takeuchi T, et al. Association of diabetic retinopathy with both sarcopenia and muscle quality in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1): e000404. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000404.

Yang Q, Zhang Y, Zeng Q, et al. Correlation between diabetic peripheral neuropathy and sarcopenia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic foot disease: a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:377–86. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S237362.

Nakanishi S, Iwamoto M, Shinohara H, et al. Impact of sarcopenia on glycemic control and atherosclerosis in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: cross-sectional study using outpatient clinical data. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(12):1196–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14063.

Ida S, Nakai M, Ito S, et al. Association between sarcopenia and mild cognitive impairment using the japanese version of the SARC-F in elderly patients with diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.012.

Zhang Y, Weng S, Huang L, et al. Association of sarcopenia with a higher risk of infection in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3478.

Miyake H, Kanazawa I, Tanaka KI, et al. Low skeletal muscle mass is associated with the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018819842971.

Kashani KB, Frazee EN, Kukralova L, et al. Evaluating muscle mass by using markers of kidney function: development of the sarcopenia index. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):e23–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002013.

Ozturk Y, Deniz O, Coteli S, et al. Global leadership initiative on malnutrition criteria with different muscle assessments including muscle ultrasound with hospitalized internal medicine patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(4):936–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpen.2230.

Osaka T, Hamaguchi M, Hashimoto Y, et al. Decreased the creatinine to cystatin C ratio is a surrogate marker of sarcopenia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:52–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.025.

Hirai K, Tanaka A, Homma T, et al. Serum creatinine/cystatin C ratio as a surrogate marker for sarcopenia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(3):1274–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.08.010.

Ulmann G, Kai J, Durand JP, et al. Creatinine-to-cystatin c ratio and bioelectrical impedance analysis for the assessement of low lean body mass in cancer patients: comparison to l3-computed tomography scan. Nutrition. 2021;81: 110895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2020.110895.

Jung CY, Joo YS, Kim HW, et al. Creatinine-cystatin c ratio and mortality in patients receiving intensive care and continuous kidney replacement therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.08.014.

Lee HS, Park KW, Kang J, et al. Sarcopenia index as a predictor of clinical outcomes in older patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103121.

Liu W, Zhu X, Tan X, et al. Predictive value of serum creatinine/cystatin c in acute ischemic stroke patients under nutritional intervention. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(3):335–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1495-0.

Li S, Lu J, Gu G, et al. Serum creatinine-to-cystatin c ratio in the progression monitoring of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Physiol. 2021;12: 664100. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.664100.

Anker SD, Morley JE, von Haehling S. Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7(5):512–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12147.

Nishimura A, Harashima SI, Hosoda K, et al. Sex-related differences in frailty factors in older persons with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018819833304.

Sugimoto K, Tabara Y, Ikegami H, et al. Hyperglycemia in non-obese patients with type 2 diabetes is associated with low muscle mass: the multicenter study for clarifying evidence for sarcopenia in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(6):1471–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13070.

Ogama N, Sakurai T, Kawashima S, et al. Association of glucose fluctuations with sarcopenia in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030319.

Pechmann LM, Jonasson TH, Canossa VS, et al. Sarcopenia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Endocrinol. 2020;2020:7841390. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7841390.

Baxmann AC, Ahmed MS, Marques NC, et al. Influence of muscle mass and physical activity on serum and urinary creatinine and serum cystatin C. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(2):348–54. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.02870707.

Pottel H, Delanaye P, Schaeffner E, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate for the full age spectrum from serum creatinine and cystatin C. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(3):497–507. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfw425.

Kruse NT, Buzkova P, Barzilay JI, et al. Association of skeletal muscle mass, kidney disease and mortality in older men and women: the cardiovascular health study. Aging. 2020;12(21):21023–36. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202135.

Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Cristini C, et al. Difficulties with physical function associated with obesity, sarcopenia, and sarcopenic-obesity in community-dwelling elderly women: the EPIDOS (EPIDemiologie de l’OSteoporose) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(6):1895–900. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2008.26950.

Landi F, Camprubi-Robles M, Bear DE, et al. Muscle loss: the new malnutrition challenge in clinical practice. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(5):2113–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.11.021.

Deutz NEP, Ashurst I, Ballesteros MD, et al. The underappreciated role of low muscle mass in the management of malnutrition. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(1):22–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.021.

Czapla M, Karniej P, Juarez-Vela R, et al. The association between nutritional status and in-hospital mortality among patients with acute coronary syndrome-a result of the retrospective nutritional status heart study (NSHS). Nutrients. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103091.

Sze S, Pellicori P, Kazmi S, et al. prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition using 3 scoring systems among outpatients with heart failure: a comparison with body mass index. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(6):476–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2018.02.018.

Ahmed N, Choe Y, Mustad VA, et al. Impact of malnutrition on survival and healthcare utilization in medicare beneficiaries with diabetes: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6(1): e000471. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000471.

Wei W, Zhang L, Li G, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of malnutrition in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease: a cohort study. Nutr Metab. 2021;18(1):102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-021-00626-4.

Mesinovic J, Zengin A, De Courten B, et al. Sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a bidirectional relationship. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019;12:1057–72. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S186600.

Kanda E, Lopes MB, Tsuruya K, et al. The combination of malnutrition-inflammation and functional status limitations is associated with mortality in hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1582. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80716-0.

Sasaki K, Shoji T, Kabata D, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation as predictors of mortality and cardiovascular events in hemodialysis patients: the dream cohort. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2021;28(3):249–60. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.56069.

Maykish A, Sikalidis AK. Utilization of hydroxyl-methyl butyrate, leucine, glutamine and arginine supplementation in nutritional management of sarcopenia-implications and clinical considerations for type 2 diabetes mellitus risk modulation. J Pers Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10010019.

Kimura T, Okamura T, Iwai K, et al. Japanese radio calisthenics prevents the reduction of skeletal muscle mass volume in people with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-001027.

Hashimoto Y, Kaji A, Sakai R, et al. Effect of exercise habit on skeletal muscle mass varies with protein intake in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes a retrospective cohort study. Nutrients. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103220.

Zhang X, Zhao Y, Chen S, et al. Anti-diabetic drugs and sarcopenia: emerging links, mechanistic insights, and clinical implications. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(6):1368–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12838.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded and supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (82170859) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province General Project (2021A1515010785).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study (HC, MT, SQC); data collection (WW, JL); data analysis and/or interpretation of data for the work (SGL, YL, KHC); drafting of the work or revising it (WW). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital ethics committee. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Consent for publication

All authors support the submission to this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Baseline characteristics of all patients.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Univariable Cox regression analysis for variables and long-term all-cause mortality.

Additional file 3: Figure S1.

Time-dependent ROC analysis for 5-year Mortality. A The cut-off value is 1.0 for men; B. The cut-off value is 0.8 for women.

Additional file 4: Figure S2.

Hazard ratios for long-term all-cause mortality in different subgroups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, W., Li, S., Liu, J. et al. Prognostic value of creatinine-to-cystatin c ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cohort study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 14, 176 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-022-00958-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-022-00958-y