Abstract

Background

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the most common causes of liver transaminases elevation and a global health concern.

Purpose

This study designed to evaluate the effects of turmeric rhizomes (Curcumalonga Linn.) on liver enzymes, Lipid profiles and Malondialdehyde (MDA) in patients with NAFLD.

Study design

Randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial.

Methods

64 cases of NAFLD randomly assigned to receive either turmeric (2 gr/day) or placebo for 8 weeks. The changes of liver transaminases, lipid profiles and MDA were measured before and after study period and compared between two groups (IRCT 2015092924262N1).

Results

At the end of the study, the Turmeric group showed a significant reduction in liver enzymes (AST before 26.81 ± 10.54 after 21.19 ± 5.67, P = 0.044, ALT before 39.56 ± 22.41, after 30.51 ± 12.61, P = 0.043 and GGT before33.81 ± 17.50, after 25.62 ± 9.88, P = 0.046) compared with the placebo group. The serum levels of triglycerides, LDL, HDL and MDA had also a significant decrease among turmeric group as compared to baseline while there was no significant change in placebo group (P < 0.05). The serum cholesterol, VLDL level and sonographic grades of NAFLD had not any significant change in both groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion this study suggests that daily consumption of turmeric (and its active phenolic ingredients as curcumin) supplementation could be effective in management of NAFLD and decreasing serum level of liver transaminases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a clinico-pathologic condition which characterized with accumulation of lipids in the liver [1, 2]. This condition is one of the most common causes of liver transaminases elevation as a global health concern and unrelated to alcohol consumption [3, 4]. NAFLD contains a wide range of disorders from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [5, 6]. Previously NAFLD has been considered as a benign condition while more recent studies have proven it as a serious and progressive disorder with raising prevalence twice in the past two decades [7, 8].

There is not any accurate estimate of NAFLD prevalence among different communities because this condition could be present in the absence of any transaminase rising even among diabetics and usually is asymptomatic [9, 10]. However, it is reported to involve 57% of obese persons, 70% of diabetics and even 90% of morbid obese population with an increasing course [11]. Fat accumulation in liver has a key role in pathogenesis of other morbid conditions such as heart failure or diabetes mellitus and could be considered as an additional feature of the metabolic syndrome, with specific hepatic insulin resistance [12, 13]. The pathogenesis of NAFLD and NASH appears to be multifactorial and many mechanisms have been proposed as possible causes of fatty liver infiltration [13, 14]. The well knows factors in induction of fatty liver include fatty acids, TNFα and adiponectin and imbalance of their concentration [15]. In this setting, the oxidative stress has a key role in progression of NAFLD [16, 17]. Oxidative stress also triggers production of inflammatory cytokines, causing inflammation and a fibrogenic response [18, 19].

The current therapeutic strategies for NASH treatment are mostly directed toward correction and modifying risk factors such as obesity, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia with especial concern toward oxidative stress [19, 20]. In this regard, several natural herbal products have the potential to be hepatoprotective and therefore can be used to treat acute and chronic liver diseases [21,22,23]. One of these hepatoprotective herbs is Turmeric (Curcuma longa) or its constituent which has been used not only as a dietary spice but also as a traditional medicine for many centuries and its properties have been reported in the literature [20, 24,25,26]. Curcumin (dihydroferuloyl-methane), a natural polyphenol, is a biologically active phytochemical substance extracted from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) [27,28,29]. Curcuma longa L. seems to posse a surprisingly wide range of pharmacologic actions, including anti-carcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory activities [28, 30]. Potential hepatoprotective activity of Turmeric and its constituent have been known in Indian traditional medicine hundreds years ago. Recent evidences have also demonstrated the efficacy of curcumin in liver function improvement [21, 30, 31]. Moreover, available evidence showed that supplementation with Curcumin may be effective for liver diseases [30,31,32]. However, some studies did not show positive effects of curcumin on liver function [33]. Due to inconsistent findings, we cannot make a certain decision on the effects of curcumin on liver enzymes. According to recent evidences, potential benefits and availability of turmeric (curcumin), this randomized clinical trial has been designed to evaluate any potential role of oral turmeric on the liver enzymes, lipid profile, malondialdehyde (MDA) and the grade of hepatic steatosis.

Materials and method

Study design

This clinical trial was approved by the Ethical Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (IR.Ajums.rec.1394.104) and study registered at IRCT.ir (IRCT 2015092924262N1). A written informed consent was signed by all of the participants at the beginning of the study.

In this clinical trial, during 3 months all of the NAFLD patients who attend at the outpatient hepatology clinic of Ahvaz Imam Hospital as a tertiary center included.

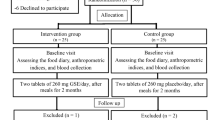

Inclusion criteria include clinical diagnosis of NAFLD and age range between 18 to 65 years. The exclusion criteria include history of advanced chronic liver disease, renal failure or any other active gastrointestinal disorder, Alcohol drinking, consumption of anticoagulants, weight-lowering agents, oral medications for diabetes mellitus, hepatotoxic medications and/or concurrent supplementation with vitamins or antioxidants. In all of the participants, NAFLD diagnosis was confirmed by expert gastroenterologist based on chronic elevation of liver enzymes, absence of alcohol consumption and an ultrasonography report of nonalcoholic fatty liver. Overall, 62 patients included and randomly divided into intervention or placebo groups (wheat flour), respectively. For all of them lifestyle modification advised. Then, the participants in intervention group supplemented with Turmeric (2 gr/daily) as oral capsules and the other group received placebo. The intervention period was 8 weeks and subjects were advised to consume their capsules after main meals to enhance absorption in the small intestine due to the presence of dietary fat. The medical history, demographic data, and diet habits of each patient were recorded by using a self-administered questionnaire at the beginning of the study. All of the participants had a weekly phone call to remind them about the supplements and they were also asked to report any adverse effects.

To evaluate dietary intake, including total energy, fat, protein, and carbohydrate, 24-h food recalls for three days (2 working days and a holiday) were obtained from all subjects before and after intervention. Nutrient intakes of the subjects were analyzed by using modified Nutritionist IV software (version 3.5.2, First Data Bank; Hearst Corp, San Bruno, CA). In order to height and weight of the participants, a measuring tape and digital scale were used, height was recorded with an accuracy of 0.1 cm while the participants were in standing and an upright position without shoes and weight was measured with minimal clothing and without shoes, with a precision of 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters. Waist circumference (WC) and hip circumference (HC) were measured by using a non-stretchable tape, without any pressure applied to the surface of the body. These measurements were recorded with a precision of 0.1 cm. After recording of anthropometric data, blood samples obtained from all of the participants before and after the 8 weeks’ intervention period. Blood samples were kept into evacuated tubes and serum of each sample was separated after centrifugation (3000 rpm, 4 °C, 15 min) by a trained examiner. Afterwards, they were stored freezer (− 70 °C) until analysis. To avoid any effect from hormonal variation, blood samples were not collected from women during their menstrual period. Hematological factors including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl Trans peptidase (GGT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and lipid profile including high-density lipoproteins (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) were determined by an automated biochemical analyzer (Hitachi-7180E, Tokyo, Japan) with a Pars Azmoon reagent kit (Tehran, Iran). The Malondialdehyde (MDA) level was determined by turbidimetric immunoassay (LDN Co., Germany). Liver Ultrasonography were performed with a 3.5/5 MHz probe at the entry and end of the study period by an expert radiologist blinded to the group allocation of the patients (General Electric LOGIQ 400 CL). The grade of hepatic steatosis, defined as the percentage of hepatocytes with fat droplets, was measured for each patient and then the degree of steatosis was categorized using the following scale: 0 (normal), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) version 18 for Windows. The normal distribution of all variables was checked with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We compared the means of variables of each group with using both independent sample t tests and analysis of covariance in the adjusted models. The end values of each variable were also compared with the baseline values using paired sample t tests. Differences with P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The baseline demographic, dietary intakes and anthropometric characters of two groups were similar (Table 1). After the study period, there was a significant decrease in the values such as weight, waist and WHR without any significant differences between 2 groups. Flowchart of the current research is shown in Fig. 1.

The levels of liver transaminases including ALT and AST in turmeric group were 39.56 ± 22.41 and 26.81 ± 10.54 which decreased to 30.51 ± 12.61 and 21.19 ± 5.67 respectively and in comparison with placebo group showed a significant difference (P = 0.043 and 0.044) (Table 2). After 8 weeks’ intervention, the serum levels of triglycerides (P = 0.043), LDL (P = 0.035), HDL (P = 0.049) and Malondialdehyde (MDA) (P = 0.0001) decreased in the turmeric group as compared to control group but in comparison with placebo group, these changes were nonsignificant. There were no significant changes in serum levels of total cholesterol (p = 0.196) and VLDL (P = 0.417) (Table 3). Sonographic degree of fatty liver did not reduce markedly in the turmeric group (P = 0.271) (Table 4); which could be related to short study period. However, intragroup differences in the turmeric-treated group showed a significant reduction in the percentages of NAFLD grades (p = 0.020, Table 2).

Discussion

We conducted a RCT of the efficacy of turmeric on some parameters of lipid profile, oxidative stress, liver echogenicity and liver functional test (AST, ALT, and GGT) among NAFLD patients. Overall the results of our study showed that supplementation with turmeric extracts (2000 mg/day) could reduce serum levels of ALT and AST. Elevated blood ALT and AST are conventional indicators of liver injury and usually measured in investigations on liver disease [34]. As mentioned, a combination of insulin resistance, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and inflammation are involved in pathogenesis of NAFLD [35,36,37]. Hence, any compound that controls all of these disorders could consider as a liver-protective compound. In the current research, supplementation with Turmeric significantly reduced serum levels of AST, ALT, and GGT. These findings was in agreement with two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses that show the beneficial impact of turmeric and its active component, curcumin supplementation on reduction of serum ALT levels in subgroups with ≥ 1000 mg/day as well as serum levels of AST in studies with 8-weeks administration [24, 25]. Moreover, another meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) indicated a considerable effect of the curcumin supplementation on lowering AST levels compared to the placebo; while, there was no significant change in ALT blood concentrations following curcumin consumption [21].

The current study also observed that turmeric supplementation for 8 weeks significantly reduced the MDA blood concentrations as a marker of lipid peroxidation, compared to baseline in patients with NAFLD. Consistent with our findings, Jakubczyk et al. recently in a meta-analysis of four RCTs demonstrated that the administration of Pure curcumin (645 mg/67 days) resulted in a significant reduction in the level of MDA as well as a increment in total antioxidant capacity [38]. Another systematic and meta-analysis reported the efficacy of purified curcuminoids supplementation in preventing the effects of oxidative stress by a considerably reduction in MDA concentrations [39]. In this case, Acar and colleagues have also addressed the ability of curcumin administration to reduce the serum MDA levels in diabetic patients [40].

The current study revealed that taking turmeric‐containing supplement for an 8-week period resulted in a significant decrease in the degree of steatosis in compare to the baseline. Given that, liver ultrasonography is a safe, inexpensive, non-invasive, and well tolerated procedure that is considered as the first-line to diagnose the severity of fatty liver diseases in the clinical and epidemiological setting [41]. In this regard, reports have illustrated considerable evidence the hepato-protective effects of turmeric to alleviate hepatic steatosis and prevent the progression of fatty liver disease in other models of hepatic dysfunction [21, 25, 41,42,43]. However, due to limited studies with long-term duration we should interpret our findings with caution. More studies are needed to clarify the efficacy of curcumin in different duration of intervention. Given the available data, the efficacy of curcumin on fatty liver diseases is still unclear in clinical trials, which needs to further research and consideration [20]. Through multiple pharmacological mechanisms, the liver-protecting effects of curcumin in vitro and in vivo studies has been highlighted. The anti-oxidant ability of curcumin in scavenging reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species and lipid radicals is one of the most important one [44, 45]. Role of oxidative stress and inflammation in inducing hepatocyte injury and progression of NAFLD have been determined in previous studies [18, 46, 47]. Curcumin, a lipid-soluble antioxidant which is located in cell membrane reacts with lipid radicals and turns to phenoxyl radical. After that it travels to the surface of the membrane and can be neutralized by water-soluble antioxidants like vitamin C [48]. Treatment with curcumin also enhances the activities of detoxifying enzymes such as glutathione-S-transferase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, catalase and heme-oxygenase-1 in liver as well as suppression the hepatic protein expression of oxidative stress [24, 26, 49,50,51]. Curcumin blocks the activation of major mediators of cellular inflammation such as NF-κB, 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2); which is implicated in the activation of many genes including several pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IFN-γ and IL-12 [52,53,54]. NF-κB can also modulate the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), an enzyme which is involved in production of nitric oxide and hepatocyte toxicity and same as cardio-protective effects in case MI among diabetics [55, 66]. Curcumin also inhibits activation and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells which have a well-known role in progression of liver fibrosis. Decreased in liver hydroxyproline content and downregulating of collagen mRNA synthesis after curcumin treatment supports this claim [56, 57, 65]. No severe adverse events were reported in our study and even available evidence. There were only one case with stomachache and two cases with combined stomachache and nausea in Rahmani et al. trial [58].

Additionally, the results of this clinical trial demonstrated that the 2 g turmeric use have a favorable effect on serum levels of TG and LDL-c. There was also a trend toward significant increase of HDL concentrations in NAFLD patient with turmeric supplementation; but no significant difference was observed in TC and VLDL serum levels. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and dyslipidemia are implicated in pathogenesis of NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [59]. Previous studies showed beneficial effects of curcumin on insulin resistance, serum glucose, body fat and serum lipids [58, 60, 61]. Improvement in these disorders could be an effective way in management of liver disease. A study by Adab et al. revealed a significant reduction in TG and LDL-c in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) after 8-weeks administration of 2100 mg turmeric powder daily; whereas, no considerable changes were seen on TC and HDL-c [39]. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis of 9 RCTs suggested curcumin supplementation effective in lowering serum TC, LDL, FBS, and waist circumference (WC) in patients with NAFLD, although not in serum TG, HDL, and body mass index (BMI) [25]. Previous systematic review and meta-analysis also represented that there was a trend to significant decrease of LDL-C, TG, FBS levels, and weight in NAFLD subjects following curcumin supplementation; however, no statistical significance change in TC and HDL- c was achieved with curcumin consumption [21]. Contrary to the results of our study, Pakfetrat et al. could not find any significant change in lipid profiles in end-stage renal disease patients who were supplemented with 1.5 g turmeric for 8 weeks [62]. In another human study, Kim et al. found that 12 weeks of fermented turmeric powder (FTP) supplementation at a dosage of 3.0 g/day no effect on serum levels of TG, total cholesterol, LDL-c, HDL-c in patients with mild to moderate elevated ALT levels [31]. Nevertheless, the sample sizes were relatively small and the obtained results were controversial. Besides, different types, dosage and preparation methods of turmeric were used among included studies, explaining that several functional compounds in turmeric may involve in its beneficial effects on liver.

Based on the RCTs, there was several plausible mechanisms in the estimates supporting favorable effect of curcumin for lowering TG and LDL-c levels and also prevention hepatic lipid accumulation [25]. A possible mechanism may be related to metabolites of absorbed curcuminoids; which can play as ligands to activate the expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) gene that implicated in intra- and extracellular lipid metabolism [63]. Considering that, PPARs play a central role in a signaling system that control lipid homeostasis. It seems that lowering serum TG and LDL-c levels are also related probably owing to a curcumin-induced increase in the expression of several enzymes involving fatty acid metabolism such as cholesterol 7a-hydroxylase, hemeoxygenase-1, and low density lipoprotein receptors and a similar decrease in the expression of HMG-CoA reductase [21]. Moreover, curcumin could lead to lowering plasma LDL-c via reduction of cholesteryl ester transfers protein (CETP) from HDL and/or enhanced clearance of plasma LDL-c. Curcumin-induced reduction of CE transfer between lipoproteins due to CETP inhibition results in decreasing LDL-c with simultaneous increasing HDL-c concentration [64].

Several limitations existed in our study. Firstly, due to ethical considerations, we could not use liver biopsy which is a more accurate diagnostic tool. Secondly, follow-up duration was not long enough to consider the effects of turmeric on the hepatic system. Thirdly, we could not exactly evaluate the loyalty of the participants to the treatments but we controlled this problem, by repeated follow-up visits and by counting the capsules.

Conclusion

In conclusion the results of our study showed that supplementation with turmeric extracts reduce elevated serum levels of ALT and AST among patients with NAFLD. Decreasing of these two enzymes could indicate improvement in liver function. Therefore, it could be considered as a good adjuvant therapeutic supplement with hypo lipidemic and antioxidant properties for this disease. However, more well-designed randomized clinical trials are needed to investigate other indicators of NAFLD. Furthermore, the beneficial role of curcumin in other liver diseases remained unclear due to the lack of trials on these populations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- GGT:

-

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoproteins

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoproteins

- VLDL:

-

Very-low-density lipoprotein

- NASH:

-

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HC:

-

Hip circumference

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- iNOS:

-

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- PPARs:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

- HMG-CoA:

-

3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A

- CETP:

-

Cholesteryl ester transfers protein

References

Baziar N, Parohan M. The effects of curcumin supplementation on body mass index, body weight, and waist circumference in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res. 2020;34(3):464–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6542.

Obika M, Noguchi H. Diagnosis and evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/145754.

Zelber-Sagi S, Ratziu V, Oren R. Nutrition and physical activity in NAFLD: an overview of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(29):3377. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i29.3377.

Hui E, Xu A, Bo Yang H, Lam KS. Obesity as the common soil of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes: role of adipokines. J diabetes Investig. 2013;4(5):413–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12093.

Marzuillo P, del Giudice EM, Santoro N. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: new insights and future directions. World J Hepatol. 2014;6(4):217. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i4.217.

Day CP. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a massive problem. Clin Med. 2011;11(2):176. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.11-2-176.

Tsochatzis EA, Papatheodoridis GV. Is there any progress in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World J gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2011;2(1):1. https://doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v2.i1.1.

Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1388–93. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-1212.

Li Z, Xue J, Chen P, Chen L, Yan S, Liu L. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mainland of China: a meta-analysis of published studies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(1):42–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12428.

Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:S5–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mcg.0000168638.84840.ff.

Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, Landt CL, Harrison SA. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(1):124–31. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.038.

Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1341–50. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0912063.

Schuppan D, Schattenberg JM. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: pathogenesis and novel therapeutic approaches. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:68–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12212.

Del Ben M, Polimeni L, Baratta F, Pastori D, Loffredo L, Angelico F. Modern approach to the clinical management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8341. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8341.

Farsi F, Mohammadshahi M, Alavinejad P, Rezazadeh A, Zarei M, Engali KA. Functions of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on liver enzymes, markers of systemic inflammation, and adipokines in patients affected by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Nutr. 2016;35(4):346–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2015.1021057.

Mohammadshahi M, Farsi F, Nejad PA, Hajiani E, Zarei M, Engali KA. The coenzyme Q10 supplementation effects on lipid profile, fasting blood sugar, blood pressure and oxidative stress status among non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. 2014;3(6):1108–13.

Madan K, Bhardwaj P, Thareja S, Gupta SD, Saraya A. Oxidant stress and antioxidant status among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(10):930–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mcg.0000212608.59090.08.

Rolo AP, Teodoro JS, Palmeira CM. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Free Radical Biol Med. 2012;52(1):59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.003.

Rezazadeh A, Mahmoodi M, Mard SA, Karimi Moghaddam E. The effects of dark chocolate consumption on lipid profile, fasting blood sugar, liver enzymes, inflammation, and antioxidant status in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. 2015;4(12):1858–64.

White CM, Lee J-Y. The impact of turmeric or its curcumin extract on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review of clinical trials. Pharm Pract. 2019. https://doi.org/10.18549/pharmpract.2019.1.1350.

Wei Z, Liu N, Tantai X, Xing X, Xiao C, Chen L, Wang J. The effects of curcumin on the metabolic parameters of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hep Intl. 2019;13(3):302–13.

Sunilson JAJ, Jayaraj P, Mohan MS, Kumari AAG, Varatharajan R. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effect of the roots of Hibiscus esculentus Linn. Int J Green Pharm. 2008. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-8258.44731.

Alavinejad SP, Eshkiki ZS, Pourmousa Z, Zaeemzadeh N, Hashemi SJ, Mard SA. A pilot study of epigallocatechin gallate treatment in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver. Iran J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;25(2):141.

Mansour-Ghanaei F, Pourmasoumi M, Hadi A, Joukar F. Efficacy of curcumin/turmeric on liver enzymes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Integr Med Res. 2019;8(1):57–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2018.07.004.

Jalali M, Mahmoodi M, Mosallanezhad Z, Jalali R, Imanieh MH, Moosavian SP. The effects of curcumin supplementation on liver function, metabolic profile and body composition in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2020;48: 102283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102283.

Sahebkar A, Serban M-C, Ursoniu S, Banach M. Effect of curcuminoids on oxidative stress: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Funct Foods. 2015;18:898–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.01.005.

Lang A, Salomon N, Wu JC, Kopylov U, Lahat A, Har-Noy O, Ching JY, Cheong PK, Avidan B, Gamus D. Curcumin in combination with mesalamine induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(8):1444–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.019.

Antiga E, Bonciolini V, Volpi W, Del Bianco E, Caproni M. Oral curcumin (Meriva) is effective as an adjuvant treatment and is able to reduce IL-22 serum levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Biomed Res Int. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/283634.

Sahebkar A, Cicero AF, Simental-Mendía LE, Aggarwal BB, Gupta SC. Curcumin downregulates human tumor necrosis factor-α levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis ofrandomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res. 2016;107:234–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.03.026.

Rivera-Espinoza Y, Muriel P. Pharmacological actions of curcumin in liver diseases or damage. Liver Int. 2009;29(10):1457–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02086.x.

Kim S-W, Ha K-C, Choi E-K, Jung S-Y, Kim M-G, Kwon D-Y, Yang H-J, Kim M-J, Kang H-J, Back H-I. The effectiveness of fermented turmeric powder in subjects with elevated alanine transaminase levels: a randomised controlled study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):58.

Panahi Y, Kianpour P, Mohtashami R, Jafari R, Simental-Mendía LE, Sahebkar A. Efficacy and safety of phytosomal curcumin in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Res. 2017;67(04):244–51. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-100019.

Navekar R, Rafraf M, Ghaffari A, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Khoshbaten M. Turmeric supplementation improves serum glucose indices and leptin levels in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36(4):261–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2016.1267597.

Yam MF, Basir R, Asmawi MZ, Ismail Z. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects of Orthosiphon stamineus Benth. standardized extract. Am J Chin Med. 2007;35(01):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0192415X07004679.

Mavrogiannaki AN, Migdalis IN. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: newer data. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;450639(10):3. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/450639.

Angelico F, Del Ben M, Conti R, Francioso S, Feole K, Fiorello S, Cavallo MG, Zalunardo B, Lirussi F, Alessandri C, Violi F. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1578–82. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1024.

Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, Romanelli AJ, Shulman GI. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(31):32345–53. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M313478200.

Jakubczyk K, Drużga A, Katarzyna J, Skonieczna-Żydecka K. Antioxidant potential of curcumin—a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Antioxidants. 2020;9(11):1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9111092.

Tabrizi R, Vakili S, Akbari M, Mirhosseini N, Lankarani KB, Rahimi M, Mobini M, Jafarnejad S, Vahedpoor Z, Asemi Z. The effects of curcumin-containing supplements on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res. 2019;33(2):253–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6226.

Acar A, Akil E, Alp H, Evliyaoglu O, Kibrisli E, Inal A, Unan F, Tasdemir N. Oxidative damage is ameliorated by curcumin treatment in brain and sciatic nerve of diabetic rats. Int J Neurosci. 2012;122(7):367–72. https://doi.org/10.3109/00207454.2012.657380.

Loria P, Adinolfi L, Bellentani S, Bugianesi E, Grieco A, Fargion S, Gasbarrini A, Loguercio C, Lonardo A, Marchesini G. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a decalogue from the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF) Expert Committee. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(4):272–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2010.01.021.

Elahi RK. Preventive effects of turmeric (Curcuma longa Linn.) powder on hepatic steatosis in the rats fed with high fat diet. Life Sci J. 2012;9(4):5462–8.

Salama SM, Abdulla MA, AlRashdi AS, Ismail S, Alkiyumi SS, Golbabapour S. Hepatoprotective effect of ethanolic extract of Curcuma longa on thioacetamide induced liver cirrhosis in rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):56.

Reddy AC, Lokesh BR. Studies on the inhibitory effects of curcumin and eugenol on the formation of reactive oxygen species and the oxidation of ferrous iron. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;137(1):1–8.

Sreejayan MN. Curcuminoids as potent inhibitors of lipid peroxidation. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1994;46(12):1013–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.1994.tb03258.x.

Mantena SK, King AL, Andringa KK, Eccleston HB, Bailey SM. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of alcohol- and obesity-induced fatty liver diseases. Free Radical Biol Med. 2008;44(7):1259–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.029.

Perez-Carreras M, Del Hoyo P, Martin MA, Rubio JC, Martin A, Castellano G, Colina F, Arenas J, Solis-Herruzo JA. Defective hepatic mitochondrial respiratory chain in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;38(4):999–1007. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50398.

Jovanovic SV, Boone CW, Steenken S, Trinoga M, Kaskey RB. How curcumin works preferentially with water soluble antioxidants. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(13):3064–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja003823x.

Piper JT, Singhal SS, Salameh MS, Torman RT, Awasthi YC, Awasthi S. Mechanisms of anticarcinogenic properties of curcumin: the effect of curcumin on glutathione linked detoxification enzymes in rat liver. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30(4):445–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1357-2725(98)00015-6.

Motterlini R, Foresti R, Bassi R, Green CJ. Curcumin, an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent, induces heme oxygenase-1 and protects endothelial cells against oxidative stress. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;28(8):1303–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00294-X.

Iqbal M, Sharma SD, Okazaki Y, Fujisawa M, Okada S. Dietary supplementation of curcumin enhances antioxidant and phase II metabolizing enzymes in ddY male mice: possible role in protection against chemical carcinogenesis and toxicity. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;92(1):33–8. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.920106.x.

Nanji AA, Jokelainen K, Rahemtulla A, Miao L, Fogt F, Matsumoto H, Tahan SR, Su GL. Activation of nuclear factor kappa B and cytokine imbalance in experimental alcoholic liver disease in the rat. Hepatology. 1999;30(4):934–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510300402.

Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(15):1066–71.

Singh S, Aggarwal BB. Activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B is suppressed by curcumin (diferuloylmethane) [corrected]. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(42):24995–5000. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.270.42.24995.

Sanz-Cameno P, Medina J, Garcia-Buey L, Garcia-Sanchez A, Borque MJ, Martin-Vilchez S, Gamallo C, Jones EA, Moreno-Otero R. Enhanced intrahepatic inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and nitrotyrosine accumulation in primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):723–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00266-0.

Park EJ, Jeon CH, Ko G, Kim J, Sohn DH. Protective effect of curcumin in rat liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000;52(4):437–40. https://doi.org/10.1211/0022357001774048.

Kang HC, Nan JX, Park PH, Kim JY, Lee SH, Woo SW, Zhao YZ, Park EJ, Sohn DH. Curcumin inhibits collagen synthesis and hepatic stellate cell activation in-vivo and in-vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2002;54(1):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1211/0022357021771823.

Rahmani S, Asgary S, Askari G, Keshvari M, Hatamipour M, Feizi A, Sahebkar A. Treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with curcumin: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2016;30(9):1540–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5659.

Gariani K, Philippe J, Jornayvaz FR. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance: from bench to bedside. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(1):16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2012.11.002.

Ismail NA, Ragab S, Abd El Baky A, Hamed M, Ibrahim A. Effect of oral curcumin administration on insulin resistance, serum resistin and fetuin-A in obese children: randomized placebo-controlled study. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2014;5:887–96.

Chuengsamarn S, Rattanamongkolgul S, Phonrat B, Tungtrongchitr R, Jirawatnotai S. Reduction of atherogenic risk in patients with type 2 diabetes by curcuminoid extract: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Biochem. 2014;25(2):144–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.09.013.

Pakfetrat M, Akmali M, Malekmakan L, Dabaghimanesh M, Khorsand M. Role of turmeric in oxidative modulation in end-stage renal disease patients. Hemodial Int. 2015;19(1):124–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/hdi.12204.

Schoonjans K, Staels B, Auwerx J. Role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) in mediating the effects of fibrates and fatty acids on gene expression. J Lipid Res. 1996;37(5):907–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2275(20)42003-6.

Shin SK, Ha TY, McGregor RA, Choi MS. Long-term curcumin administration protects against atherosclerosis via hepatic regulation of lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(12):1829–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201100440.

Zarei M, Acharya P, Talahalli RR. Ginger and turmeric lipid-solubles attenuate heated oil-induced hepatic inflammation via the downregulation of NF-kB in rats. Life Sci. 2021;15(265): 118856.

Boarescu PM, Boarescu I, Bocșan IC, Gheban D, Bulboacă AE, Nicula C, Pop RM, Râjnoveanu RM, Bolboacă SD. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin nanoparticles on drug-induced acute myocardial infarction in diabetic rats. Antioxidants. 2019;8(10):504.

Acknowledgements

Maryam Jarhahzadeh contributed as DATA collector. Pezhman Alavinejad has been the correspoder of the study. Farnaz Farsi participated as clinical nutritionist and cooperated in article writing. Durdana Husain participated as nutritional consultant. Afshin Rezazadeh has performed the ultrasonography of participants.

Funding

This work was supported by Alimentary Tract Research Center of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences without any financial grant. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJ participate as clinical nutritionist, PA as corresponding author and clinical hepatologist, FF as consultant nutritionist and participant in final draft preparation, DH as consultant nutritionist and supervisor and AR as radiologist operated ultra-sonographies. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study approved by the Ethical Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (IR.Ajums.rec.1394.104).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

jarhahzadeh, M., Alavinejad, P., Farsi, F. et al. The effect of turmeric on lipid profile, malondialdehyde, liver echogenicity and enzymes among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized double blind clinical trial. Diabetol Metab Syndr 13, 112 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00731-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00731-7