Abstract

Background

Deterioration of sleep quality has been reported to contribute to the incidence of diabetes and may be responsible for glycemic status in diabetes. The present study explored the relationship between sleep quality and glycemic variability in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Methods

We recruited 111 patients with T2D for this cross-sectional study. Each patient underwent flash glucose monitoring for 14 days to obtain glycemic variability parameters, such as standard deviation of glucose (SD), coefficient of variation of glucose (CV), mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE), mean of daily differences (MODD), and time in glucose range of 3.9–10 mmol/L (TIR3.9–10). After 14 days of flash glucose monitoring, each patient received a questionnaire on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to evaluate subjective sleep quality. HbA1c was also collected to assess average glucose.

Results

HbA1c was comparable among the subgroups of PSQI score tertiles. Across ascending tertiles of PSQI scores, SD, CV and MAGE were increased, while TIR3.9–10 was decreased (p for trend < 0.05), but not MODD (p for trend = 0.090). Moreover, PSQI scores were positively correlated with SD, CV, MODD and MAGE (r = 0.322, 0.361, 0.308 and 0.354, respectively, p < 0.001) and were inversely correlated with TIR3.9–10 (r = − 0.386, p < 0.001). After adjusting for other relevant data by multivariate linear regression analyses, PSQI scores were independently responsible for SD (β = 0.251, t = 2.112, p = 0.041), CV (β = 0.286, t = 2.207, p = 0.033), MAGE (β = 0.323, t = 2.489, p = 0.018), and TIR3.9–10 (β = − 0.401, t = − 3.930, p < 0.001) but not for MODD (β = 0.188, t = 1.374, p = 0.177).

Conclusions

Increased glycemic variability assessed by flash glucose monitoring was closely associated with poor subjective sleep quality evaluated by the PSQI in patients with T2D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glycemic variability, defined as the instability between high and low values of glycemia [1], has been demonstrated to stimulate oxidative stress and provoke proinflammatory mediators [2,3,4], which in turn lead to various vascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [5,6,7]. Moreover, glycemic variability is independent of average glucose levels reflected by glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and diabetic patients with comparable HbA1c may present with different features of glycemic variability [8, 9] and subsequent diabetic complications [10]. At present, ongoing research efforts worldwide are trying to screen intrinsic and external risk factors for increased glycemic variability, which can help guide the development of appropriate therapeutic regimens to improve glycemic variability and subsequent diabetic prognosis.

Currently, several technologies are available to quantitatively assess all-day glycemic variability, such as continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems (such as systems from Medtronic MiniMed Inc.) for 3–7 days and flash glucose monitoring (FGM) systems (such as the systems from Abbott Inc.) for 14 days, which can present a full range of glycemic variability in any time period [11, 12]. A fully detailed profile of glycemic variability may facilitate screening the risk factors for increased glycemic variability.

Sleep is a necessary part of human daily life, and a good quality of sleep is essential to human physical and mental recovery after exhausting work. Conversely, deterioration in sleep quality was reported to account for a wide spectrum of adverse health outcomes, such as chronic metabolic diseases, malignant tumors, adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality [13,14,15,16]. Accordingly, in several previous studies, poor sleep quality was demonstrated to contribute to glycemic disturbances and the occurrence and progression of diabetes [17, 18]. Thus, we hypothesized that poor sleep quality may be an important risk factor for increased glycemic variability. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is a potent tool to assess subjective sleep quality and is widely applied in sleep studies [19, 20].

Therefore, our present study was conducted to determine whether there was a possible relationship between subjective sleep quality assessed by the PSQI and glycemic variability indices acquired from the FGM system in T2D patients.

Methods

Participant recruitment

We released a notification to recruit participants for this study from the Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Hospital 2 of Nantong University, between December 2019 and January 2021. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (1) aged from 25 to 70 years; (2) diagnosis of T2D referring to the statement released by the American Diabetes Association in 2015 [21]; and (3) consent to join the study. The exclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (1) type 1 diabetes or presence of diabetes-related antibodies; (2) history of malignancy; (3) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; (4) severe cardio-cerebrovascular diseases, such as myocardial and cerebral infarction; (5) chronic liver and kidney diseases; (6) severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; (7) hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism; (8) current use of glucocorticoids; (9) serious psychiatric diseases; and (10) connective tissue diseases. Ultimately, 111 eligible patients with full data were pooled for statistical analyses. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital 2 of Nantong University, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, all participants provided informed consent when they were recruited into the study.

Clinical data collection

Clinical data of participants were collected when they were screened by medical history, physical examination and biochemical tests. Relevant data for the final analysis included age, sex, waist circumference (WC), height, weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), history of hypertension and glucose-lowering therapies. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on weight and height (kg/m2). Hypertension was defined as we described in our previous study [22]. Glucose-lowering therapies in our study were classified into lifestyle alone, insulin treatments, insulin secretagogues, metformin, pioglitazone, α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4Is) and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2Is).

Fasting blood samples were drawn to assess triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC), creatinine (Cr), uric acid (UA) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was acquired using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation [23].

All patients also received a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for the assessment of α-cell and β-cell functions. Venous blood samples were drawn at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min after glucose loading to synchronously determine serum glucose, C-peptide and glucagon levels. Overall glucose levels were measured by the area under the glucose curve (AUCglu). Overall, α-cell and β-cell functions were measured by the area under the glucagon curve (AUCgluca) and the area under the C-peptide curve (AUCcp), respectively [24, 25].

Assessment for glycemic variability

After initial screening, eligible patients with T2D were detected by a flash continuous glucose monitoring (FGM) system for 14 days. The FGM system we used in the present study is a hospital version (FreeStyle™ Libre H, Abbott Diabetes Care Ltd., Witney, Oxon, UK), which contains three parts: a sensor kit, a reader and a software for downloading glucose data from the reader. During the FGM, the individualized plan for daily dietary energy intake was prepared by nutritionists, which was also described in our previous study [22]. The sensor kit can store glucose data at 15-min intervals. To make sensor’s glucose data blind to the patients during the FGM, a reader was not provided to the patients. The sensor’s glucose data were unblinded to the patients after they completed the PSQI questionnaire on the last day of FGM. After 14 days of FGM, glucose data could be downloaded from the reader by the FGM software, the software then generated ambulatory glucose profile (AGP) reports [26], and the time in glucose range from 3.9 to 10 mmol/L (TIR3.9–10) could be obtained from the AGP reports. Other multiple glycemic variability indices, including standard deviation of glucose (SD), coefficient of variation of glucose (CV), mean of daily differences (MODD), and mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE), could be calculated from the downloaded glucose data. The methods of calculation were also described in our previous studies [22, 27] and other studies [7, 28].

Subjective measurement for sleep quality

After 14 days of FGM, all participants received a Chinese version of the PSQI questionnaire by face-to-face interviews to measure subjective sleep quality [29, 30]. The PSQI, a self-evaluation of sleep quality in the past month, has 19 items, 9 questions and 7 component scales. The 7 components are listed below: (1) subjective sleep quality; (2) sleep latency; (3) sleep duration; (4) sleep efficiency; (5) sleep disturbances; (6) use of sleep medication; and (7) daytime dysfunction. Each component is rated equally on a 0–3 scale, and the 7 components are then pooled to generate total PSQI scores ranging from 0 to 21. Higher PSQI scores represent poorer quality of sleep, which indicates that 0 is better than 21. The Chinese version of the PSQI had an overall reliability coefficient of 0.82–0.83 and an acceptable test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.85 for all subjects [30].

Statistical analyses

Clinically relevant data of recruited patients with T2D are exhibited for the total and three subgroups according to the tertiles of PSQI scores. Continuous and categorical data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and frequency (percentage), respectively. We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a linear trend to explore trends in continuous data among PSQI score tertiles and used the chi-squared test with linear-by-linear association to explore trends in categorical data among PSQI score tertiles. In addition, we used Pearson’s correlation analysis to explore the correlation of PSQI scores with multiple glycemic variability parameters.

Furthermore, multivariate linear regression analysis was used to adjust for other clinically relevant variables to explore the independent effects of PSQI scores on multiple glycemic variability parameters. In each regression analysis, the initial Model 0 was unadjusted; Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, WC, SBP, DBP and diabetes duration; Model 2 was further adjusted for hypertension and glucose-lowering therapies; and Model 3 was further adjusted for eGFR, UA, lipid profiles, HbA1c, AUCglu, AUCcp and AUCgluca.

We used SPSS for Windows, standard version 19.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), to input and analyze the data. Statistical significance was determined by a p value < 0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics of participants

The clinical characteristics of the recruited patients with T2D are displayed in Table 1. The mean PSOI score of all recruited patients was 6.9 ± 2.9, and the range of PSOI scores was 1–16. The ranges of the PSQI score tertiles were 1–4 (first tertile, T1), 5–7 (second tertile, T2) and 8–16 (third tertile, T3). From T1, T2, to T3 of PSQI scores, SD, CV and MAGE were notably increased, while TIR3.9–10 was decreased (p for trend < 0.05), but not MODD (p for trend = 0.090). Moreover, across ascending tertiles of PSQI scores, TC levels were significantly increased, but age, ratio of females, BMI,WC, SBP, DBP, diabetes duration, hypertension prevalence, TG, HDLC, LDLC, UA, eGFR, AUCglu, AUCcp, AUCgluca and HbA1c did not show any differences among the tertiles of PSQI scores. Regarding glucose-lowering therapies, the frequency of metformin use was increased when the tertiles of PSQI scores increased, but lifestyle alone, insulin treatments, insulin secretagogues, AGIs, DPP-4Is and SGLT-2Is were comparable among the tertiles of PSQI scores.

Correlations between PSQI scores and multiple glycemic variability parameters

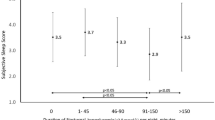

Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that SD, CV, MODD and MAGE were positively correlated with PSQI scores (r = 0.322, 0.361, 0.308 and 0.354, respectively, p < 0.001), while TIR3.9–10 was negatively correlated with PSQI scores (r = − 0.386, p < 0.001). These correlations are also graphically displayed in Fig. 1. Additionally, the corrections of the 7 components in the PSQI with multiple glycemic variability parameters are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Overall, subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency and daytime dysfunction were related to glycemic variability parameters.

Scatter plots for the correlations of multiple glycemic variability parameters with PSQI scores. A standard deviation of glucose (SD); B coefficient of variation of glucose (CV); C mean of daily differences (MODD); D mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE); E time in glucose range of 3.9–10 mmol/L (TIR3.9–10)

Multivariate linear regression analyses exploring the independent effects of PSQI scores on multiple glycemic variability parameters

The effects of the PSQI scores on the outcomes of multiple glycemic variability parameters by multivariate linear regression analyses are shown in Table 2. In the initial unadjusted Model 0, PSQI scores were independently associated with SD (β = 0.322, t = 3.551, p = 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.104), CV (β = 0.361, t = 4.307, p < 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.130), MODD (β = 0.308, t = 3.381, p = 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.095), MAGE (β = 0.354, t = 3.948, p < 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.125), and TIR3.9–10 (β = − 0.386, t = − 4.373, p < 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.149). After adjusting for other clinically relevant variables by multivariate linear regression analyses, the adjusted R2 was revealed to gradually increase from Model 0 to Model 3. In fully adjusted Model 3, PSQI scores remained independently associated with SD (β = 0.251, t = 2.112, p = 0.041), CV (β = 0.286, t = 2.207, p = 0.033), MAGE (β = 0.323, t = 2.489, p = 0.018), and TIR3.9–10 (β = − 0.401, t = − 3.930, p < 0.001) but not with MODD (β = 0.188, t = 1.374, p = 0.177).

Discussion

In the present study, we systemically analyzed the relationship between sleep quality assessed by PSQI scores and glycemic variability assessed by FGM in 111 patients with T2D. The main findings of our study were as follows: first, PSQI scores were closely correlated with multiple glycemic variability parameters by univariate analysis, including SD, CV, MODD, MAGE and TIR3.9–10; second, PSQI scores were independently associated with SD, CV, MAGE and TIR3.9–10 by multivariate linear regression analysis, but not with MODD; third, HbA1c was comparable among the subgroups of PSQI score tertiles, which may suggest that poor subjective sleep quality may have effects on glycemic variability, but not on HbA1c; fourth, after adjusting for other relevant clinical data, each one-point increment in PSQI scores may correspond to an SD increase of 0.251 mmol/L, a CV increase of 0.286%, a MAGE increase of 0.323 mmol/L and a TIR3.9–10 decrease of 0.401%.

Classical glycemic variability parameters and adverse consequences

It is well known that increased glycemic variability is independently associated with a variety of adverse outcomes [31]. Classical glycemic variability parameters, calculated from detailed glycemic profiles obtained by CGM or FGM, including SD, CV, MODD, MAGE and TIR3.9–10, have been widely applied in clinical studies. Glycemic variability has its own independent potential to prompt oxidative stress and subsequent adverse health outcomes. As early as 2006, Monnier et al. [4] demonstrated that MAGE was closely associated with urinary 8-iso prostaglandin F2α in patients with T2D, which indicated that glycemic variability could induce a special effect on oxidative stress and paved the road linking glycemic variability to diabetic complications. Ohara et al. [3] also demonstrated that day-to-day glycemic variability assessed by MODD was related to diacron-reactive oxygen metabolites reflective of oxidative stress. Moreover, with respect to diabetic complications, SD was recognized as a significant risk factor for diabetic retinopathy in patients with pooled type 1 diabetes and T2D [32], and CV was closely connected to the prevalence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in patients with T2D [7]. In addition, increased MAGE was not only found to be associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with T2D but could also predict major adverse cardiovascular events in patients who had experienced acute myocardial infarction [5, 33]. Furthermore, TIR3.9–10 has been the center of much attention in recent years. Decreased TIR3.9–10 was revealed to be associated with diabetic retinopathy [34], painful diabetic polyneuropathy [35], impaired peripheral nerve functions [36], increased carotid intima-media thickness [37] and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy [38] in patients with T2D. Therefore, screening modifiable risk factors for increased glycemic variability would be of significance.

Possible risk factors for increased glycemic variability

Accumulated studies have revealed the intrinsic and external risk factors for increased glycemic variability. Our previous studies have shown that impaired islet β-cell function may account for increased glycemic variability in subjects at high risk for diabetes and in patients with T2D [39, 40], which was consistent with a prior study by Kohnert et al. [41] in T2D using oral hypoglycemic agents. Correspondingly, glycemic variability could be attenuated by improvement in β-cell function [42]. Moreover, increased glycemic variability may also be related to lower levels of fasting C-peptide, longer diabetic duration in T2D using insulin, older age, obesity, higher TG, lower LDLC and the use of sulfonylurea in T2D without insulin treatment [43]. In addition, abnormal glucagon secretion [44], hyperthyroidism [45], higher serum thyrotropin [22], more severe dawn phenomenon [46] and acute stress conditions [47] could prompt glycemic variability. Furthermore, in our present study, poor subjective sleep quality estimated by the PSQI may lead to deterioration in glycemic variability.

Poor sleep quality and adverse consequences

Normal sleep is a physiological process for energy restoration and replenishment and serves a reparative role in physical and mental fatigue relief. Normal sleep is characterized by decreases in glucose turnover and metabolic demand. Sleep inefficiency or poor sleep quality was demonstrated to be responsible for obesity [48], hypertension [49], type 2 diabetes [50], gestational diabetes mellitus [51], cardiovascular disease [14], and prognosis of chronic diseases [52]. In our present study, we found that multiple glycemic variability parameters, such as SD, CV, MODD, MAGE and TIR3.9–10, were correlated well with subjective sleep quality. In the final analysis, subjective sleep quality may independently account for SD, CV, MAGE and TIR3.9–10. More surprisingly, HbA1c was comparable among the subgroups of PSQI score tertiles. These results suggested that poor subjective sleep quality may have effects on glycemic variability but not on HbA1c. Approaches to improve sleep quality may facilitate the amelioration of glycemic variability.

Underlying mechanism for the linkage of sleep quality to glycemic variability

Several studies have suggested multiple pathways in the possible connection between poor sleep quality and increased glycemic variability. These pathways involve impaired cerebral glucose utilization, a hyperactive sympathetic system, the release of proinflammatory cytokines, rhythmic alterations in cortisol and growth hormone secretion, abnormalities in adipocyte function and dysregulation in appetite-regulating hormones [53, 54]. During the period of sleep deprivation, cerebral glucose utilization was revealed to be markedly reduced, notably in some cortical and subcortical regions [55]. After poor sleep quality, the sympathetic nervous system is overactivated, which in turn leads to insulin resistance and aberrant glucagon secretion [54, 56]. Consistently, elevation of systemic inflammatory responses in relation to sleep restriction was also well demonstrated, and proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and C-reactive protein were released and subsequently promoted insulin resistance [57, 58]. Moreover, increased cortisol secretion in the afternoon and evening and prolonged growth hormone secretion at night due to sleep restriction could also facilitate insulin resistance [59, 60]. Additionally, abnormalities in adipocyte function were proven to be connected to adverse metabolic consequences after poor sleep quality. Sleep restriction may account for a 30% reduction in the efficiency of the insulin signaling pathways in adipocytes [61]. Furthermore, appetite-regulating hormones were found to be dysregulated during sleep restriction; for example, leptin, a satiety hormone, was decreased, while ghrelin, a hunger hormone, was increased [62]. These changes in appetite-regulating hormones may be responsible for increases in food intake and body mass and subsequent insulin resistance. Therefore, as a result of insufficient sleep, numerous risk factors for the above suggestive pathways could cross-promote with each other, induce insulin resistance, and facilitate islet β-cell dysfunction and the incidence of T2D, ultimately contributing to the increased glycemic variability.

Strengths

Our present study exhibits several strengths. First, our study may be the first to explore the relationship between subjective sleep quality assessed by PSQI and glycemic variability assessed by FGM in patients with T2D. Second, the FGM data were blinded to the patients during FGM detection. Third, multiple glycemic variability parameters were applied in our present study, especially TIR3.9–10, which has received extensive attention because of its central role in diabetic complications.

Limitations

Several limitations of our present study should be recognized. First, our study was cross-sectionally conducted and may not conclude a causal relationship between poor sleep quality and increased glycemic variability. A longitudinal study must be performed to compensate for this defect. Second, our study is restricted to the Chinese population with T2D in a single center, and the findings have limited generalizability. Third, the PSQI is a self-report measurement to subjectively assess sleep quality over the previous month. Our study lacks an objective measure for sleep, such as polysomnography (PSG), but PSG is restricted to monitoring sleep for only one or two nights. It would be ideal to combine PSQI with PSG for sleep studies.

Conclusions

In summary, increased glycemic variability assessed by FGM was closely associated with poor sleep quality assessed by the PSQI score in patients with T2D, which indicated that clinical strategies targeting improving sleep quality may ameliorate glycemic variability.

Availability of data and materials

The current data are available to all interested researchers upon reasonable request. Requests for access to data should be made to the principal investigators of the study.

Abbreviations

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes

- FGM:

-

Flash glucose monitoring

- CGM:

-

Continuous glucose monitoring

- SD:

-

Standard deviation of glucose

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation of glucose

- MAGE:

-

Mean amplitude of glycemic excursions

- MODD:

-

Mean of daily differences

- TIR3. 9–10 :

-

Time in glucose range of 3.9–10 mmol/L

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- SBP/DBP:

-

Systolic/diastolic blood pressure

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- AGIs:

-

α-Glucosidase inhibitors

- DPP-4Is:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

- SGLT-2Is:

-

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- HDLC:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDLC:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- UA:

-

Uric acid

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- OGTT:

-

Oral glucose tolerance test

- AUCglu :

-

Area under the glucose curve

- AUCgluca :

-

Area under the glucagon curve

- AUCcp :

-

Area under the C-peptide curve

References

Service FJ. Glucose variability. Diabetes. 2013;62(5):1398–404.

Chang CM, Hsieh CJ, Huang JC, Huang IC. Acute and chronic fluctuations in blood glucose levels can increase oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49(Suppl 1):S171–7.

Ohara M, Fukui T, Ouchi M, Watanabe K, Suzuki T, Yamamoto S, et al. Relationship between daily and day-to-day glycemic variability and increased oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;122:62–70.

Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, Michel F, Villon L, Cristol JP, et al. Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1681–7.

Su G, Mi S, Tao H, Li Z, Yang H, Zheng H, et al. Association of glycemic variability and the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:19.

Torimoto K, Okada Y, Mori H, Tanaka Y. Relationship between fluctuations in glucose levels measured by continuous glucose monitoring and vascular endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:1.

Jun JE, Jin SM, Baek J, Oh S, Hur KY, Lee MS, et al. The association between glycemic variability and diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:70.

Vigersky RA. Going beyond HbA1c to understand the benefits of advanced diabetes therapies. J Diabetes. 2019;11(1):23–31.

Bloomgarden Z. Beyond HbA1c, second take. J Diabetes. 2019;11(6):416–7.

Xu F, Zhao LH, Su JB, Chen T, Wang XQ, Chen JF, et al. The relationship between glycemic variability and diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes with well-controlled HbA1c. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6(1):139.

Dunn TC, Xu Y, Hayter G, Ajjan RA. Real-world flash glucose monitoring patterns and associations between self-monitoring frequency and glycaemic measures: a European analysis of over 60 million glucose tests. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:37–46.

Danne T, Nimri R, Battelino T, Bergenstal RM, Close KL, DeVries JH, et al. International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(12):1631–40.

Zuraikat FM, Makarem N, Redline S, Aggarwal B, Jelic S, St-Onge MP. Sleep regularity and cardiometabolic heath: is variability in sleep patterns a risk factor for excess adiposity and glycemic dysregulation? Curr Diab Rep. 2020;20(8):38.

Yin J, Jin X, Shan Z, Li S, Huang H, Li P, et al. Relationship of sleep duration with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9):e005947.

Xiao Q, Keadle SK, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. Sleep duration and total and cause-specific mortality in a large US cohort: interrelationships with physical activity, sedentary behavior, and body mass index. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(10):997–1006.

Lou P, Zhang P, Zhang L, Chen P, Chang G, Zhang N, et al. Effects of sleep duration and sleep quality on prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 5-year follow-up study in China. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109(1):178–84.

Tang Y, Meng L, Li D, Yang M, Zhu Y, Li C, et al. Interaction of sleep quality and sleep duration on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chin Med J. 2014;127(20):3543–7.

Tsai YW, Kann NH, Tung TH, Chao YJ, Lin CJ, Chang KC, et al. Impact of subjective sleep quality on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fam Pract. 2012;29(1):30–5.

Zhang C, Zhang H, Zhao M, Li Z, Cook CE, Buysse DJ, et al. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of Pittsburgh sleep quality index in community-based centenarians. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:573530.

Xu C, Zhang P, Xiang Q, Chang G, Zhang M, Zhang L, et al. Relationship between subjective sleep disturbances and glycaemia in Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes: findings from a 1.5-year follow-up study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):14276.

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl):S8–16.

Su JB, Zhao LH, Zhang XL, Cai HL, Huang HY, Xu F, et al. High-normal serum thyrotropin levels and increased glycemic variability in type 2 diabetic patients. Endocrine. 2018;61(1):68–75.

Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247–54.

Zhao L, Ma J, Wang S, Xie Y. Relationship between β-cell function, metabolic control, and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(1):29–34.

Wang H, Cao J, Su JB, Wang XQ, Wang X, Zhang DM, et al. Serum fatty acid-binding protein 4 levels and responses of pancreatic islet β-cells and α-cells in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2021;13(1):70.

Distiller LA, Cranston I, Mazze R. First clinical experience with retrospective flash glucose monitoring (FGM) analysis in South Africa: characterizing glycemic control with ambulatory glucose profile. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10(6):1294–302.

Hu YM, Zhao LH, Zhang XL, Cai HL, Huang HY, Xu F, et al. Association of glycaemic variability evaluated by continuous glucose monitoring with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Endocrine. 2018;60(2):292–300.

Hill NR, Oliver NS, Choudhary P, Levy JC, Hindmarsh P, Matthews DR. Normal reference range for mean tissue glucose and glycemic variability derived from continuous glucose monitoring for subjects without diabetes in different ethnic groups. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(9):921–8.

Lou P, Qin Y, Zhang P, Chen P, Zhang L, Chang G, et al. Association of sleep quality and quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study in China. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107(1):69–76.

Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, Su CT, Yang TT, Huang CJ, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(8):1943–52.

Colette C, Monnier L. Acute glucose fluctuations and chronic sustained hyperglycemia as risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39(9):683–6.

Sartore G, Chilelli NC, Burlina S, Lapolla A. Association between glucose variability as assessed by continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and diabetic retinopathy in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50(3):437–42.

Su G, Mi SH, Tao H, Li Z, Yang HX, Zheng H, et al. Impact of admission glycemic variability, glucose, and glycosylated hemoglobin on major adverse cardiac events after acute myocardial infarction. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1026–32.

Lu J, Ma X, Zhou J, Zhang L, Mo Y, Ying L, et al. Association of time in range, as assessed by continuous glucose monitoring, with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(11):2370–6.

Yang J, Yang X, Zhao D, Wang X, Wei W, Yuan H. Association of time in range, as assessed by continuous glucose monitoring, with painful diabetic polyneuropathy. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12(5):828–36.

Li F, Zhang Y, Li H, Lu J, Jiang L, Vigersky RA, et al. TIR generated by continuous glucose monitoring is associated with peripheral nerve function in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;166:108289.

Guo Q, Zang P, Xu S, Song W, Zhang Z, Liu C, et al. Time in range, as a novel metric of glycemic control, is reversely associated with presence of diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy independent of HbA1c in Chinese type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:5817074.

Lu J, Ma X, Shen Y, Wu Q, Wang R, Zhang L, et al. Time in range is associated with carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22(2):72–8.

Chen T, Xu F, Su JB, Wang XQ, Chen JF, Wu G, et al. Glycemic variability in relation to oral disposition index in the subjects with different stages of glucose tolerance. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5:38.

Su JB, Chen T, Xu F, Wang XQ, Chen JF, Wu G, et al. Glycemic variability in normal glucose regulation subjects with elevated 1-h postload plasma glucose levels. Endocrine. 2014;46(2):241–8.

Kohnert KD, Augstein P, Zander E, Heinke P, Peterson K, Freyse EJ, et al. Glycemic variability correlates strongly with postprandial beta-cell dysfunction in a segment of type 2 diabetic patients using oral hypoglycemic agents. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1058–62.

Kramer CK, Choi H, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Glycemic variability in patients with early type 2 diabetes: the impact of improvement in beta-cell function. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):1116–23.

Jin SM, Kim TH, Bae JC, Hur KY, Lee MS, Lee MK, et al. Clinical factors associated with absolute and relative measures of glycemic variability determined by continuous glucose monitoring: an analysis of 480 subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;104(2):266–72.

Li K, Song WJ, Wu X, Gu DY, Zang P, Gu P, et al. Associations of serum glucagon levels with glycemic variability in type 1 diabetes with different disease durations. Endocrine. 2018;61(3):473–81.

Torimoto K, Okada Y, Arao T, Mori H, Yamamoto S, Narisawa M, et al. Glucose variability before and after treatment of a patient with Graves’ disease complicated by diabetes mellitus: assessment by continuous glucose monitoring. Endocr J. 2014;61(4):321–8.

Monnier L, Colette C, Sardinoux M, Baptista G, Regnier-Zerbib A, Owens D. Frequency and severity of the dawn phenomenon in type 2 diabetes: relationship to age. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2597–9.

Waeschle RM, Moerer O, Hilgers R, Herrmann P, Neumann P, Quintel M. The impact of the severity of sepsis on the risk of hypoglycaemia and glycaemic variability. Crit Care. 2008;12(5):R129.

Mesarwi O, Polak J, Jun J, Polotsky VY. Sleep disorders and the development of insulin resistance and obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2013;42(3):617–34.

Gangwisch JE, Feskanich D, Malaspina D, Shen S, Forman JP. Sleep duration and risk for hypertension in women: results from the nurses’ health study. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26(7):903–11.

Ayas NT, White DP, Al-Delaimy WK, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, et al. A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(2):380–4.

Wang H, Leng J, Li W, Wang L, Zhang C, Li W, et al. Sleep duration and quality, and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant Chinese women. Diabet Med. 2017;34(1):44–50.

Ricardo AC, Knutson K, Chen J, Appel LJ, Bazzano L, Carmona-Powell E, et al. The association of sleep duration and quality with CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(12):3708–15.

Reutrakul S, Van Cauter E. Interactions between sleep, circadian function, and glucose metabolism: implications for risk and severity of diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311:151–73.

Reutrakul S, Van Cauter E. Sleep influences on obesity, insulin resistance, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2018;84:56–66.

Thomas M, Sing H, Belenky G, Holcomb H, Mayberg H, Dannals R, et al. Neural basis of alertness and cognitive performance impairments during sleepiness. I. Effects of 24 h of sleep deprivation on waking human regional brain activity. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(4):335–52.

Tentolouris N, Argyrakopoulou G, Katsilambros N. Perturbed autonomic nervous system function in metabolic syndrome. Neuromolecular Med. 2008;10(3):169–78.

Mullington JM, Simpson NS, Meier-Ewert HK, Haack M. Sleep loss and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24(5):775–84.

Faraut B, Boudjeltia KZ, Vanhamme L, Kerkhofs M. Immune, inflammatory and cardiovascular consequences of sleep restriction and recovery. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(2):137–49.

Buxton OM, Pavlova M, Reid EW, Wang W, Simonson DC, Adler GK. Sleep restriction for 1 week reduces insulin sensitivity in healthy men. Diabetes. 2010;59(9):2126–33.

Broussard JL, Chapotot F, Abraham V, Day A, Delebecque F, Whitmore HR, et al. Sleep restriction increases free fatty acids in healthy men. Diabetologia. 2015;58(4):791–8.

Broussard JL, Ehrmann DA, Van Cauter E, Tasali E, Brady MJ. Impaired insulin signaling in human adipocytes after experimental sleep restriction: a randomized, crossover study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(8):549–57.

Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):846–50.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was Funded by the Social Development Projects of Nantong (MS12019019, HS2020005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY, LhZ, JbS and LhW participated in the design of the study, analysis of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. YY, JbS and LhW conceived of the study, participated in its design, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. YY, LhZ, DdL, FX, XhW, CfL, ChW, CY, XlZ, LyN and XqW participated in the data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital 2 of Nantong University, and its conduction was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, all participants provided informed consent when they were enrolled in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Relationships between the 7 components of the PSQI and glycemic variability parameters in patients with T2D.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Zhao, Lh., Li, Dd. et al. Association of sleep quality with glycemic variability assessed by flash glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr 13, 102 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00720-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00720-w