Abstract

Background

Traumatic pneumopericardium is rare and usually results from blunt injury. Diagnosis through clinical and chest X-ray is often difficult. Ultrasound findings of A-line artifacts in the cardiac window may suggest pneumopericardium.

Case presentation

A young man involved in a car accident and sustained blunt thoracic injuries, among others. As part of primary survey, FAST scan was performed. Subxiphoid view to look for evidence of pericardial effusion showed part of the cardiac image obscured by A-lines. Other cardiac windows showed only A-lines, as well. A suspicion of pneumopericardium was raised and CT scan confirmed the diagnosis.

Conclusions

Although FAST scan was originally used to look for presence of free fluid, with the knowledge of lung ultrasound for pneumothorax, our findings suggest that FAST scan can also be used to detect pneumopericardium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pneumopericardium is defined as the presence of air inside the pericardium region and it is commonly found in infants with positive pressure ventilation. In adults, pneumopericardium is a rare and usually results from penetrating or blunt chest injuries or after thoracotomy [1, 2]. Clinical diagnosis is very difficult, if not impossible. Diagnosis is by chest X-ray and is again difficult, the gold standard being computed tomography (CT) scan. Focused assessment of sonography in trauma (FAST) scan is traditionally used to detect pericardial effusion. We report a case of utilizing FAST scan to diagnose pneumopericardium in a trauma patient.

Case presentation

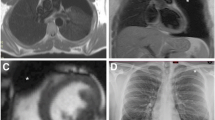

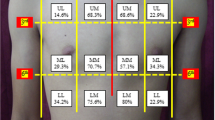

A 27-year-old male involved in a motor vehicle accident was brought to Emergency Department room with respiratory distress. He was intubated upon arrival due to low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) with extensive maxillofacial injuries. Thoracic examination showed reduced air entry at right chest wall region with palpable crepitus on his right neck region due to subcutaneous emphysema from the neck to the anterior chest wall. The heart sound was barely audible. A curvilinear transducer on the right second intercostal ribs shows the absence of sliding signs, suggestive of right pneumothorax. A FAST scan was performed, but, on subxiphoid view of the heart, only the right ventricle is seen during diastole. Part of the cardiac image was obscured by A-lines (Fig. 1). This raised a suspicion of pneumopericardium given the subxiphoid window was showing partly A-lines and the other half of anatomy partially obscured. We proceeded with focused cardiac ultrasound, and only A-lines were visible on parasternal long axis (PLAX), parasternal short axis (PSAX), and apical four chamber (A4C) views.

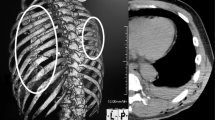

The patient underwent head and chest CT scan that confirmed the diagnosis of Le Fort II facial bone injury, right pneumothorax, and right pulmonary contusion with pneumopericardium (Fig. 2). The pneumopericardium was treated conservatively, but other injuries were treated accordingly.

Discussion

The first sonographic evaluation of pneumomediastinum was first described as “air gap sign” [1]. It was described as a broad band of echoes due to accumulation of air obscuring the anterior wall of the heart, with drop out echoes posteriorly. Pneumomediastinum appeared cyclically with the cardiac cycle [3]. In 1994, Allgood et al. [4] described sonographic pneumopericardium findings as the inability to view the heart at the subxiphoid area. This was due to a potential space behind the pericardium that extended inferiorly to the posterior of the pericardium. However, in pneumomediastinum, the heart can be visualized at the subxiphoid area as it was well intact with the diaphragm without obstruction of the air. If there is air in the abdomen (pneumoperitoneum) or if the presence of large gastric bubble, this can obscure the subxiphoid view, thus differential of pneumopericardium and pneumomediastinum can be difficult. The difference in ultrasound findings between pneumopericardium and pneumomediastinum was recently described by Zachariah et al. [5]. In pneumomediastinum, the subxiphoid window remained clear and anatomy is not obscured, suggesting that diaphragm, pericardium, and myocardium were still intact and not obstructed by air. In pneumopericardium, views for parasternal long, parasternal short apical four chambers, and subxiphoid view were poor quality with diffuse A-lines, suggesting air artifact.

Point-of-care ultrasound performed at bedside can lead to a diagnosis that clinical examination alone would not have revealed. Pneumopericardium is not an easy diagnosis to make either clinically or sonographically. Although there is the literature describing pneumopericardium findings, to the best of our knowledge, there is no previous report for trauma cases. FAST scan is a standard ultrasound protocol and is used as an adjunct in primary survey according to the ATLS guidelines. However, the purpose of FAST was to look for free fluid in pericardial and peritoneal regions and, of recent years, presence of haemo- and pneumothorax. With the advancement of knowledge in ultrasound, FAST protocol can be taken to another level. The placement of the probe at the same place as in FAST scan, other pathologies can also be identified, such as atelectasis and diaphragmatic hernia [6, 7]. In our case, partial visualization of the cardiac image with the presence of A-lines on subxiphoid view, coupled with A-lines on all other cardiac views, is highly suggestive of pneumopericardium.

Conclusion

The role of FAST scan has evolved over the years. As we have now incorporated the detection of pneumothorax and call it extended focused assessment of sonography in trauma (E-FAST), treating physicians must be aware of other possible diagnosis that can be detected with FAST scan. We suggest that the presence of cardiac A-lines in subxiphoid cardiac view should alert the physician to the probability of pneumopericardium.

Abbreviations

- FAST:

-

focused assessment of sonography in trauma

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- GCS:

-

Glasgow coma scale

- PLAX:

-

parasternal long axis

- PSAX:

-

parasternal short axis

- A4C:

-

apical four chamber

- ATLS:

-

advanced trauma life support

- E-FAST:

-

extended focused assessment of sonography in trauma

References

Cummings RG, Wesly RL, Adams DH, Lowe JE (1984) Pneumopericardium resulting in cardiac tamponade. Ann Thorac Surg 37(6):511–518

Hymes WA, Itani KM, Wall MJ Jr, Granchi TS, Mattox KL (1994) Delayed tension pneumopericardium after thoracotomy for penetrating chest trauma. Ann Thorac Surg 57(6):1658–1660

Reid CL, Chandraratna PA, Kawanishi D, Bezdek WD, Schatz R, Nanna M, Rahimtoola SH (1983) Echocardiographic detection of pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium: the air gap sign. J Am Coll Cardiol 1(3):916–921

Allgood NL, Brownlee JR, Green GA (1994) Inability to view the heart through the subxiphoid echocardiographic window: a harbinger of disaster. Pediatr Cardiol 15:27–29

Zachariah S, Gharahbaghian L, Perera P, Joshi N (2015) Spontaneous pneumomediastinum on bedside ultrasound: case report and review of the literature. West J Emerg Med 16(2):321

Yang JX, Zhang M, Liu ZH, Ba L, Gan JX, Xu SW (2009) Detection of lung atelectasis/consolidation by ultrasound in multiple trauma patients with mechanical ventilation. Crit Ultrasound J 1(1):13–16

Tjhia J, Noor JM (2018) Beyond E-FAST scan in trauma: Diagnosing of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with bedside ultrasound. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 25(3):163–165

Authors’ contributions

Both authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript equally. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This manuscript has received approval and consent National Medical Research Register, Ministry of Health, Malaysia (NMRR-18-2634-43967 S1).

Fundings

The authors do not receive any funding.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Md Noor, J., Eddie, E.A. Cardiac A-lines in fast scan as a sign of pneumopericardium. Ultrasound J 11, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-019-0123-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-019-0123-x