Abstract

The triggers and pathogenesis of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) are not yet completely understood. However, therapeutic agents targeting tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-17 inflammatory pathways have proven successful in suppressing many of the clinical symptoms and signs of axSpA, giving us an indication of which pathways are responsible for initiating and maintaining the inflammation. The mechanisms that eventuate in syndesmophytes and ankyloses are less clear. This review addresses these two critical pathways of inflammation, discussing their nature and these factors that may activate or enhance the pathways in patients with axSpA. In addition, genetic and other markers important to the inflammatory pathways implicated in axSpA are explored, and prognostic biomarkers are discussed. Treatment options available for the management of axSpA and their associated targets are highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is the prototypical form of a family of diseases known as spondyloarthritis (SpA) characterized by inflammatory processes and new bone formation [1, 2]. Inflammation, bone and cartilage loss, and subsequent remodeling with new bone formation take place in the entheses, axial skeleton, and peripheral joints. Critically, axSpA encompasses two conditions: ankylosing spondylitis (AS), which presents with radiographic damage and ankyloses of the sacroiliac joint (as defined and validated by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society [ASAS] classification criteria) [3, 4], and nonradiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA), which does not show radiographic changes but may describe inflammation to the sacroiliac joint by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS), or computed tomography [5, 6]. The prevalence of axSpA in the USA is estimated to be 0.7%, with AS and nr-axSpA each accounting for 0.35% of patients [7]. Patients with axSpA also present with a range of extra-articular manifestations, including inflammatory bowel lesions, psoriasis, and uveitis [1, 8, 9]. Thus, axSpA is a potentially debilitating disease, associated with chronic pain, deformities, and reduced function and quality of life [10, 11].

The pathogenesis of axSpA appears to be multifactorial, arising from several exogenous factors, engaging genetic susceptibilities to amplify multiple inflammatory and innate and acquired immune responses, and eventuating in musculoskeletal damage and repair. Clinically, the initiating factors include biomechanical stresses affecting the tissues and cells of the entheses, where tendons and ligaments bind to the fibrocartilage and bone. McGonagle and colleagues [12] substantiated the concepts of tissue micro-damage, whereby stresses in the synovial–entheseal complex trigger interleukin (IL)-23 from macrophages, dendritic cells, and possibly group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s) to initiate inflammation in the adjoining fibrocartilage, bursae, fat pad, deep fascia, synovium, and cortical and trabecular bone. The most stressed regions occur in the sacroiliac, spinal, sternoclavicular, manubriosternal, and acromioclavicular joints, rather than in peripheral joints [13, 14].

Another critical initiating factor may come from infectious signals generated from commensal bacteria within the gut microbiome, which moderate immune homeostasis of the innate and innate-like cells at the barrier sites [15, 16]. In axSpA, innate mesenchymal stem cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells permit expression of IL-23 receptor-positive ILCs in the gut, blood, synovial fluid, and bone marrow, and IL-23–positive cells in spinal facet joints, which activate the IL-23/IL-17 axis of pro-inflammatory cytokines [17, 18]. In addition, the mechanisms that activate monocytes with lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and other bacterial adjuvants and recruit neutrophils to the entheses may be strong contributing factors to both the production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) and the activation of osteoblasts [19]. Interestingly, increased levels of monocyte/macrophage migration inhibition factor (MIF) in peripheral blood correlate with disease activity and predict spinal syndesmophyte progression [20]. Furthermore, elevated autoantibodies to the CD74 receptor for MIF are considered to be a diagnostic marker for axSpA, even in patients who do not express human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 [21].

Susceptibility to axSpA in people with the HLA-B27 and HLA-B40 genes has been elegantly proposed; however, clear and consistent agreement across studies is lacking. It is not clear whether HLA and non-HLA genes and polymorphisms of the IL23R gene permit a lower threshold of mechanical stress or LPS levels to be activated, although increased gut permeability has been proposed. In addition, the chronic nature of the inflammatory immune responses in axSpA may be due to aberrant peptide processing and presentation, sustained triggering of inflammatory pathways, and failure of inflammation to resolve in these HLA-B27 and HLA-B40 genetically predisposed individuals [9, 22]. Furthermore, what triggers and maintains new bone formation and ankyloses in axSpA is not fully understood, and it is not clear which therapeutic modalities can clearly arrest the deformities caused by new bone formation.

It is strongly suggested that the earliest therapies to forestall inflammation will restrict damage and subsequent bone formation and ankyloses and thus allow patients to maintain function and quality of life. The latest recommendations reinforce the concept of treating towards defined and validated measures of disease activity, as assessed by the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), or the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), recording improvement based on achievement of ASAS20 or ASAS40, and changing therapies if ASDAS scores do not indicate remission (i.e., scores < 1.3) or ASAS partial remission scores do not decrease by at least two units on a 0-to-10 scale in four domains. Secondly, clinical practice has validated that therapeutic successes depend on the educated patient who has committed to mutually agreed-upon goals with the rheumatologist, who regularly communicates the clinical data [23,24,25].

Methods

Targeted PubMed literature searches were conducted to identify articles that discussed inflammatory pathways and genes involved in the development of axSpA. Searches were conducted using combinations of search terms, including “ankylosing spondylitis,” “axial spondyloarthritis,” “inflammation,” “pathway,” “pathogenesis,” “gene,” “biomarker,” “polymorphism,” “bone formation,” “bone loss,” “comorbidities,” “IL-1,” “IL-6,” “IL-17,” “IL-23,” and “TNF/tumor necrosis factor.” Search results were supplemented based on the reference citations in articles identified in initial searches and based on the authors’ familiarity with the published literature. Articles were qualitatively selected for inclusion in this review if they presented results that the authors deemed relevant.

Therapies

The mainstay of pharmacologic treatment for both AS and nr-axSpA begins with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [26], which inhibit the cyclooxygenase (COX) activity of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 initiates inflammation by activating macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, and site-specific stromal and vascular endothelial cells and facilitates the transition from innate to acquired immune responses by enhancing the IL-23/IL-17 axis and developing the regulatory T cell. Specifically, PGE2 acts on T-helper (Th)1 and Th17 cells via its EP2 and EP4 receptors in the presence of IL-1β and IL-23; receptor polymorphisms may affect the efficacy of COX inhibitors in axSpA [27]. Inhibiting PGE2 resolves entheseal inflammation, relieves pain, inhibits vasodilation, and retards bone formation, particularly if used continuously rather than intermittently, as confirmed by ultrasound and x-rays [28, 29]. Thus, NSAID therapies are strongly recommended [23, 25, 30].

The traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine, were not found to be effective in controlling AS or nr-axSpA [26, 31]. However, analysis of data from the Swedish Biologics Register showed that the combination of conventional synthetic DMARDs (especially methotrexate) with TNF inhibition enhances retention to anti-TNF therapy [32].

Data from clinical trials have described that inhibitors of IL-1 [33] and IL-6 [34], as well as therapy with abatacept [35, 36] and rituximab (CD20) [37], did not appear to be useful in AS. Rather, the current therapeutic approach that is strongly recommended for the treatment of axSpA (regardless of whether or not radiographic disease is present) [26] centers on the use of biologic treatments directed at more precise cytokine targets, including TNFα [11, 38,39,40] and IL-23/IL-17 [41, 42]. Thus, we will address first the TNF and IL-17 pathways, including the nature of the pathways, and the factors that may activate or enhance the pathways in patients with axSpA or in animal models or in vitro experiments. Second, genetic and other markers important to the initial and then continuing inflammatory pathways implicated in axSpA will be described, including the sparse emerging data on prognostic biomarkers. Finally, the range of treatment options available for the management of axSpA and their associated targets will be explored.

The inflammatory process: role of TNF and IL-17/IL-23

Cytokines produced by various cells play an important role in driving the immune response in axSpA and other inflammatory arthritic diseases. Advances in molecular and immunologic research over the past three decades have repeatedly supported the key role of cytokine dysregulation in the pathophysiology of auto-inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including axSpA [9].

TNF

Several lines of evidence implicate TNF in the pathogenesis of axSpA; however, the exact TNF-associated cellular and molecular mechanisms involved are not well understood [2]. TNF, a 233 amino acid protein, is synthesized as a transmembrane protein (tmTNF), in a trimeric form which can be cleaved by a converting enzyme to a soluble molecule (sTNF). Both act by binding to two receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) 1 and TNFR2, activating multiple cellular pathways ranging from cell homeostasis and proliferation via nuclear factor (NF)-κB and protective immunity from infections and cell death via the caspases, respectively (Fig. 1) [2]. Additionally, tmTNF can act as a ligand by binding cell-to-cell to TNF receptors and as a receptor that transmits reverse or outside-to-inside signals to induce local inflammation within the tmTNF-bearing cells. [43].

Inflammatory Pathways in axSpA. In spondyloarthritis, biomechanical stress and inflammatory factors, including infectious antigens, amplified by MHC susceptibility genes, HLA-B27 variants, and ERAP1 SNP transcription factors induce specific cell types to produce a series of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-23, IL-17, TNF, IL-1, and IL-6. Hematopoietic stem cells elaborate NF-κB, RANKL, and M-CSF to differentiate monocytes to osteoclasts, which extend inflammatory damage in the supporting structures of the sacroiliac and peripheral joints. Mesenchymal stem cells facilitated by Wnt and BMP differentiate to osteoblasts to form new bone and ankyloses. BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CRP, C-reactive protein; DKK, Dickkopf; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; ERAP1, endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1; IL, interleukin; ILC-3s, group 3 innate lymphoid cells; M-CSF, monocyte colony-stimulating factor; MMP, metalloproteinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; OPG, osteoprotegerin; OSX, osterix zinc finger-containing transcription factor; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand; RUNX, runt-related transcription factor; SFRP, secreted frizzled-related proteins; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SOX9, sex-determining region Y transcription factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. Italicized = transcription factor; red = inflammation; blue = bone formation/ankylosis. Th1 cells = T helper cells for humoral immunity; Th17 cells = T helper cells for IL-17 inflammation, damage

Key TNF signaling pathways include TNFR1 or TNFR superfamily type 1A (TNFRSF1A), TNFR1-associated death domain (TRADD), and TNFSF15 [1, 2, 44]. TNFR1 signaling is associated with NF-κB–mediated cell survival and growth and/or apoptosis through the TRADD adaptor protein [2]. TNFR2 is predominantly produced by cells of immunologic and endothelial origin, and is also associated with NF-κB activation [2, 45]. Overexpression of TNF has been documented in the sacroiliac joints of patients with AS, and patients with AS have been shown to have high levels of the circulating soluble TNF receptors (sTNF-R1 and sTNF-R2) [46].

IL-23/IL-17 axis

Immunologic studies have strongly implicated the IL-23/IL-17 axis in axSpA [2, 9]. Macrophages, dendritic cells, ILCs, and mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAITs) contribute to elevated IL-23 levels found in the serum, inflamed gut, synovial fluid, entheses, and bone-derived cells, including the marrow, and fibrous tissues taken from the peripheral joints of patients with AS [47,48,49,50,51,52]. In addition, IL-17–positive mast cells and neutrophils have been reported in facet joints [53], and IL-22 levels have been shown to be elevated in the gut of patients with AS [54]. Macrophages from patients with AS stimulated by Toll-like receptor agonists such as LPS produced IL-23; and IL-23 enhanced IL-17 production from pathogenic Th17 cells [55].

In response to IL-23, additional cells, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the microenvironment of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and transcriptional regulators (e.g., signal transducer and activation of transcription [STAT] 3, RAR-related orphan receptor γt [RORγt]), drive Th17 cells to produce IL-17 and other cytokines, including IL-6, IL-22, IL-26, and TNF in a reciprocating continuum [9, 56, 57]. The gut microbiome may also contribute, as serum amyloid A from the terminal ileum induces Th17 cell differentiation from naïve CD4+ T lymphocytes, and microbiota-induced IL-1β stimulates development of Th17 lymphocytes in the intestine [58].

Some have proposed that HLA-B27 misfolding and homodimer formation triggers IL-23 and IL-17 production through unfolded protein response and autophagy, further supporting the link between the IL-23/IL-17 pathway and the development of axSpA [2, 59]. This supports the emerging role of a pathogenic IL-23/IL-17 axis in axSpA [55, 60].

Genes and cytokines associated with axSpA

Extensive genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and other studies have identified genes involved in the development of axSpA, providing further insight into potential therapeutic and diagnostic targets (Table 1) [2, 22, 61,62,63]. Axial spondyloarthritis appears to have high heritability, not only in terms of susceptibility but also in determining disease severity and functional incapacity [64]. The gene-encoding HLA-B27, found within the major histocompatibility region, is the most well-established genetic marker for axSpA [65,66,67]. Approximately 90% to 95% of Caucasian patients with axSpA are positive for HLA-B27, compared with only 6% to 8% of the general population [68,69,70,71]. Wide ethnic variability in HLA-B27 expression exists in patients with SpA [72]. Although the canonical function of HLA-B27 is to present antigens to CD8+ T cells, much of the altered innate immune response in SpA may be related to cytoplasmic functions, which prepare the peptide for effective presentation [1]. Thus, changes in the ubiquitination process, which direct proteins to the subcellular proteasome and aminopeptidase trimming of peptides, are important processes that are associated with axSpA [73]. Indeed, endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase (ERAP)1 and ERAP2 have also been associated with axSpA, with ERAP1 conferring a relative attributable risk to AS of approximately 25% [74].

One review identified more than 41 genes predisposing to AS [75]. A meta-analysis identified 905 differentially expressed genes in AS, which included 482 upregulated genes and 423 downregulated genes [76]. In particular, polymorphisms involved in the innate immune system (CARD9) and cytokine signaling pathways, including TNF, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-23/IL-17 axes, appear to be strongly associated with the development of SpA, as per their suggestive effect on Th17-mediated immunity [1, 2].

Epigenetics, the study of mechanisms that determine and perpetuate heritable genomic functions without alteration in the DNA sequence, add to the complexity of our understanding of the pathogenesis of axSpA. These changes may account for the heterogeneity of clinical features and response to targeted therapies observed across patient subgroups [77]. Epigenetics, including histone modifications, acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation, and microRNA, may also help to explain the influence of environmental risk factors on genetic variation and their contribution to phenotypic variation among patients with axSpA [77]. Although multiple studies have demonstrated that tissue-specific epigenetic modifications play a role in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, data in axSpA remain to be described and validated [77, 78]. Indeed, because genes mostly function by interacting with each other and their actions are largely dependent on their cell and tissue context, continuing GWAS may require specific cell analyses correlating with imaging and biopsy data to discover pathogenetic effects.

Biologic agents for the treatment of axSpA

The advent of biologic agents has expanded the axSpA treatment armamentarium. Treatment with biologic agents is recommended for patients with AS who have persistently high disease activity despite conventional treatments [79, 80]. Treatment with biologic agents is also recommended for patients with nr-axSpA, with the specification in the European Union that these drugs only be used in patients with objective signs of inflammation (e.g., elevated C-reactive protein [CRP] and/or inflammation of the sacroiliac joints or spine on MRI) [26].

TNF blockade

The strongest evidence supporting the role of the TNF pathway in the pathophysiology of axSpA comes from the use of TNF inhibitors in the clinical setting. TNF inhibitors are effective in reducing pain and stiffness and improving function in patients with AS [81]. TNF inhibitors reduce inflammation in most patients, but may not provide long-term remission. Recent studies now demonstrate that TNF blockers slow spinal radiographic progression by reducing disease activity (e.g., based on changes in the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score [mSASSS]) [82]. Complete inhibition of radiographic progression is possible, as evidenced by patients who have reached an inactive disease state, defined as ASDAS < 1.3; significant reduction in disease activity is defined as ASDAS < 2.1 [2, 81, 83, 84]. However, a reported 20% to 30% of patients with axSpA do not respond adequately to TNF inhibitors, resulting in the need for other treatment options [85].

For patients who do show an initial response to TNF inhibition, treatment persistence of 5 years has shown sustained efficacy and sustained benefits in spinal mobility, disease activity, physical function, and health-related quality of life [86, 87]. After 1 year of treatment with adalimumab, ASAS20 and ASAS40 responses were achieved by 82% and 62% of patients, respectively, and after 5 years of treatment with adalimumab, ASAS20 and ASAS40 clinical responses were achieved by 89% and 70% of patients, respectively [86]. Furthermore, adalimumab and etanercept increased spine and femoral neck bone mineral density of patients with active AS with low bone mineral density [88]. Interestingly, TNF blockade did not influence the IL-23/Th17 axis, but TNF blockade did significantly reduce the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP levels [89].

TNF inhibitors approved for the treatment of AS include adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, infliximab, and golimumab (Table 2). Adalimumab and etanercept are also approved for nr-axSpA in Europe, and certolizumab pegol is approved for nr-axSpA in the US and Europe. Comparative efficacy analyses indicate that all five of the approved TNF inhibitors provide comparable ASAS responses, with similar safety profiles [90]. Notably, the effects of different TNF inhibitors on the extra-articular manifestations of axSpA are not equivalent. For example, infliximab provides better improvement in acute anterior uveitis than etanercept and adalimumab, and etanercept is not an effective treatment for inflammatory bowel disease [85].

IL-17 blockade

Results of clinical trials aimed at blocking the IL-23/IL-17 axis in patients with AS support involvement of this pathway in the pathogenesis of axSpA [2]. As such, IL-17 has emerged as a novel therapeutic target in AS. Secukinumab is the only IL-17A inhibitor currently indicated for the treatment of AS (Table 2) [41, 91]. Secukinumab demonstrated efficacy comparable to the TNF inhibitors clinically in a patient population that included both individuals with and without prior exposure to TNF inhibitors [41, 42]. Secukinumab (10 mg/kg) given intravenously at weeks 0, 2, and 4, then subcutaneously (150 mg or 75 mg) every 4 weeks was associated with ASAS20/40 response rates of 61%/42% compared with 29%/13% with placebo (P < 0.001 for both) at week 16 [42]. When secukinumab was given only subcutaneously, ASAS20/40 was achieved by 61%/36% and by 41%/26% of patients treated with secukinumab 150 mg and 75 mg, respectively, compared with 28%/11% with placebo [42]; responses were maintained at week 52 [92]. The efficacy of secukinumab has also been demonstrated over 2 years in patients who are TNF naïve (ASAS20/40 response rates at week 104 of 77%/56% with secukinumab 150 mg and 80%/60% with secukinumab 75 mg) [92]. Further, an observational study of treatment with secukinumab (2 × 10 mg/kg intravenous loading doses followed by 3 mg/kg intravenously every 4 weeks for 94 weeks) reported low progression of spinal radiographic changes with 87% of the inflammatory vertebral edges and 30% of vertebral edges with fatty lesions at baseline resolved by week 94 [93].

Ixekizumab, an IL-17 inhibitor in an IgG4 formulation, has been approved for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and is under investigation for treatment of AS (NCT02696785). At 16 weeks, ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 or 4 weeks elicited ASAS 20/40 response rates of 69%/52% and 64%/48%, respectively, compared with 40%/18% with placebo (P < 0.01 for all) and 59%/36% with adalimumab. In addition, there were significant reductions in spinal inflammation measured by MRI Spondylitis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) spine score change from baseline [94]. Studies of ixekizumab (NCT02696798) and the IL-17RA inhibitor brodalumab (NCT02985983) are ongoing in patients with axSpA.

The dual IL-17A and IL-17F inhibitor, bimekizumab, has also demonstrated therapeutic potential for the treatment of AS. In a phase 2b study, 12 weeks of treatment was associated with an ASAS40 response rate of up to 47% compared to 13% with placebo (P < 0.001) [95].

Of great interest would be the use of bispecific biologic therapies that inhibit both TNF and IL-17 [96]. Dual inhibition of these cytokines was more effective at suppressing arthritis in a collagen-induced arthritis model than TNF inhibition alone [97].

IL-12/IL-23 blockade

Ustekinumab, a human IgG1κ monoclonal antibody that binds to the common p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, failed to meet the primary endpoint of a phase 3 study in patients with AS naïve to TNF inhibitors (NCT02437162). At week 24, ASAS40 was achieved by 31% of patients receiving ustekinumab 45 mg, 28% of patients receiving ustekinumab 90 mg, and 28% of patients receiving placebo. Additional phase 3 studies of ustekinumab in AS refractory to TNF inhibitors (NCT02438787) and nr-axSpA (NCT02407223) were terminated based on this result [98].

Similarly, risankizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody specific for the IL-23 p19 subunit, failed to meet the primary endpoint of a phase 2 study in biologic naïve patients with AS [99]. At week 12, ASAS40 response rates were 25% with risankizumab 18 mg, 21% with risankizumab 90 mg, 15% with risankizumab 180 mg, and 18% with placebo. Tildrakizumab, another IL-23 p19 monoclonal antibody, is in development for axSpA (NCT02980705). There are no currently planned studies of the IL-23 p19 monoclonal antibody, guselkumab, in AS.

The negative results from these studies of ustekinumab and risankizumab were surprising and have led to speculation about the differing biologic mechanisms that occur with IL-23 versus IL-17 inhibition. There may be pathogenic differences between inflammation at spinal and peripheral sites, possibly related to different mechanical load and stress responses of ligament and tendon insertions through PGE2 activation of ILC3s and production of IL-17 via an IL-23–independent pathway [100]. Of particular interest, recent studies using single-cell–based technology found that ILC3s were not a significant source of IL-17 in the joints of patients with peripheral SpA [101, 102]. It has also been hypothesized that IL-23 may play a pathogenic role in only certain stages of axSpA (e.g., during initiation but not established disease), suggesting that higher serum concentrations of IL-23 inhibitors may be necessary to have clinically meaningful effects [100].

JAK blockade

The Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT pathway is thought to activate the IL-23/IL-17 cytokine axis, and inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway has been proposed as a therapeutic strategy in AS [103]. In a phase 2 trial, the JAK 1/3 inhibitor tofacitinib demonstrated clinical efficacy in patients with AS [104]. At 12 weeks, tofacitinib 5 mg BID elicited ASAS20/40 response rates of 81%/46%; however, placebo responses were also high (41%/20%). Subanalysis discovered that the best responders were those with high CRP and higher MRI SPARCC scores. Indeed, the improvement in SPARCC sacroiliac joint and spine scores showed a dose response [104].

IL-6 blockade

While serum IL-6 levels have been shown to be elevated in patients with AS, a recently published phase 2/3 study failed to demonstrate clinical benefit with tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor–targeted monoclonal antibody, in TNF inhibitor-naïve patients with AS [34]. A related phase 3 trial in patients with AS who had an inadequate response to previous TNF inhibitor therapy was subsequently terminated (NCT01209689). A phase 2 study of sarilumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, in TNF inhibitor-naïve patients with active AS also failed to show a clinical benefit [105].

IL-1 blockade

The IL-1 receptor family–specifically IL-1β–is a therapeutic target for several systemic and local auto-inflammatory conditions [106]. Two open-label studies have been conducted to investigate anakinra (an IL-1–receptor antagonist) in patients with AS. A pilot study suggested that anakinra may be effective in controlling AS symptoms; however, another study demonstrated limited improvement in only a small subgroup of patients with AS [33, 107].

Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibition

A phase 3 randomized, double-blind study of apremilast, a selective inhibitor of PDE4, did not meet its primary endpoint of ASAS20 compared with placebo (32.5% vs 36.6%; P = 0.4383) in 490 patients with active AS [108].

Mechanisms of bone formation and loss: Wnt pathway

Both cartilage and diffuse bone loss and pathologic new bone formation can be observed simultaneously in axSpA [2]. Mechanisms of inflammation are closely linked with bone metabolism and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with bone loss [109]. Activated T lymphocytes and osteoblasts express receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL), a key regulator of bone remodeling via receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK)/RANKL/osteoprotegerin signaling, and both TNF and IL-1 induce RANKL resulting in bone loss [109]. Three other important pathways in bone remodeling are the wingless proteins/Dikkopf-1 (Wnt/DKK-1), secreted frizzled-related proteins and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathways, which are affected by inflammation (Fig. 1) [109,110,111].

There is a dissociation of TNF-dependent inflammatory processes and TNF-independent bone-formation processes in axSpA, which may be triggered by mechanical and inflammatory stress [112, 113]. Radiographs are slow in documenting a decrease in new bone formation in patients with AS receiving TNF inhibitors when compared to historical controls [112, 114], and recent data with internal controls document less ankyloses with TNF inhibitor therapies [6]. MRI records decreases of bone marrow edema that lead to ankylosis [115] as anti-TNF therapies inhibit in vitro bone resorption by osteoclast precursor cells generated from peripheral blood with RANKL [116].

Indeed, TNF inhibitors may passively allow new bone formation to occur. TNF stimulates expression of DKK-1, which suppresses signaling by Wnt, a family of key mediators of osteoblast bone formation [117]. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by DKK promotes osteoblast and osteoclast formation and differentiation induced by BMP-2 [118]. These findings suggest that when anti-TNF therapies reduce inflammation, restoration of Wnt and BMP pathway signaling may occur, allowing the potential for new bone formation [2, 83, 119,120,121]. Additionally, therapeutic approaches are being investigated to activate the Wnt pathway, as antibodies targeting sclerostin and DKK-1 have shown promotion of bone formation and fracture healing for those with osteoporosis [122].

In animal models, IL-23R+ cells and RORγt+CD4-CD8- T cells (which are responsive to IL-23) reside in the axial and peripheral entheseal interface between the tendon and bone [123,124,125]. Importantly, in B10.RIII mice, systemic expression of IL-23 sufficiently induced enthesitis in both the front and back paws without synovial joint destruction and promoted IL-17 and IL-22 expression by these entheseal cells. This process required recombinase activating gene (Rag)-dependent cells and occurred independently of Th17 cells, which is consistent with the primary role of IL-23 cells in enthesitis. Furthermore, systemic expression of IL-22 resulted in increased STAT3 phosphorylation in the bone and induced genes encoding Wnt family members, BMP, and alkaline phosphatase. Together these results indicate that the pathophysiology of enthesitis is mediated by IL-23 and its downstream targets, IL-17 and IL-22, whereas IL-22 is specifically involved in the osteoproliferation component of the disease [123].

Next-generation clinical tools and biomarkers

ASAS classification and response criteria are valuable tools for most clinicians. However, they are based on patient-reported outcome measures, including pain, stiffness, fatigue, and patient global assessments, which can have high levels of both inter- and intra-individual variability and bias [126]. Thus, use of more objective measures should be considered in combination with ASAS criteria.

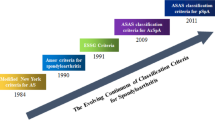

Imaging

Imaging techniques, such as conventional radiography, bone scintigraphy, MRI, and PDUS, are used for the diagnosis of axSpA, monitoring disease activity, and assessing structural damage. Initially, the New York criteria for diagnosis of AS required radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis [127, 128]. Sacroiliitis appears only after several years of undiagnosed inflammatory back pain symptoms, while MRI has demonstrated that osteitis or bone marrow edema in the sacroiliac joint is present earlier—before it becomes radiographically detectable [127, 129]. Thus, MRI is increasingly being used to detect sacroiliitis early in patients with axSpA, particularly utilizing coronal and axial sequences and high-resolution erosion-specific sequences [127, 130,131,132].

MRI is useful for following therapeutic outcomes. Anti-TNF with infliximab therapy decreased spinal and sacroiliac osteitis scores more effectively than nonsteroidal therapies [133]. Similarly, anti-IL-17A therapy with secukinumab over 2 years decreased spinal osteitis scores and fatty lesions, which eventuate to ankyloses [93].

PDUS to identify increased vascular flow is also a highly sensitive and less costly tool for detecting enthesitis, which is not always detectable by clinical examination [134]. However, this method is limited by operator proficiency [125] and its use in sacroiliitis needs confirmation. In vivo probing of TNF for guidance of therapy using 99m Tc-labeled anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies and specific aptamers are proposed [135].

Serum/tissue biomarkers

Investigations into the discovery of circulating and tissue-related biomarkers are ongoing. These biomarkers may help accurately diagnose axSpA, predict disease activity/progression, and improve response to therapy. The most frequently used axSpA marker in the clinical setting for diagnosis is HLA-B27 [136]. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP are not always dependable biomarkers for monitoring disease activity, but if elevated, predict better responses to biologic therapies and more comorbidities. [136]. Other research has focused on examining the prognostic value of cytokines, particularly IL-17 and IL-23, and downstream matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) markers such as MMP-3 (stromelysin-1), which degrades collagen II, III, IV, IX, X, and the extracellular matrix proteins. Markers of bony metabolism have also been investigated, including adipokines and cartilage/connective tissue degradation products [75]. However, no individual prognostic biomarker for disease activity has demonstrated adequate reproducibility, and an unmet need for robust biomarkers remains [75]. Biomarkers from the specific inflamed sites may be more informative and descriptive than from peripheral blood samples.

Predictive markers

Various biomarkers have been investigated for their predictive value to treat axSpA. For example, in patients with axial and peripheral SpA, infliximab treatment response is associated with high-sensitivity CRP and calprotectin levels [137], while response to golimumab in patients with AS is associated with various combinations of markers comprising specific biomarker signatures [138]. Furthermore, secukinumab response after 6 weeks of treatment in patients with AS is associated with a decrease in levels of S100A8 and S100A9, which form calprotectin, the calcium-binding protein used as a marker of gut inflammation [41].

Conclusions

As we learn about the complexities of the pathogenetic mechanisms that eventuate in axSpA, we cannot be surprised by the different clinical presentations and the variability of the individual responses to different therapies as the disease progresses over time. Each individual, possessed with different genetic susceptibilities, will undergo different initiating factors that will subject their specific cells to be activated by a varying milieu of pro-inflammatory and suppressive cytokines, chemokines, and transcriptional factors in different sites.

All agree that early diagnosis of axSpA is important because earlier treatment provides a more favorable prognosis, as irreversible structural damage occurs as the disease progresses. An early diagnosis of axSpA can also prevent the use of unnecessary diagnostic procedures and suboptimal treatments [139, 140].

Inhibition of TNF, IL-17, and other downstream cytokines and translational factors can reverse spinal inflammation. Careful clinical studies are required to differentiate if primary non-responders to either TNF or IL-17 inhibition will respond more effectively to other classes of therapy. Co-medication with conventional (NSAIDs) and newer downstream (JAK-STAT) therapies may be the next therapeutic recommendations to address the different treatment goals of controlling inflammation and subsequent bone damage [32]. Biomarkers recovered from the peripheral blood or from localized sites may predict susceptibility, activity, and clinical response to different therapies, but few are consistent and panels may be required. Accordingly, the current recommendations for changes to different therapies from knowledgeable investigators will be updated as clinical and translational studies continue. Thus, it will require careful clinical and imaging studies, especially in countries with a single medical care and documentation system, to differentiate whether any of the individual or combination therapies will modify bone damage and formation.

Finally, the rheumatologist undertakes the basic responsibility to educate and communicate, empowering the patient to be a committed partner in setting therapeutic goals, enabling the early referral of primary care physicians, and collaborating with the referring physician, therapist, primary care orthopedist, ophthalmologist, gastroenterologist, and other members of the healthcare team to promote exercise, smoking cessation, and high-quality continuing care. Thus, the rheumatologist who understands the significance of all of the clinical, imaging, genetic, and outcomes data is still the best decider of individual therapies.

Abbreviations

- AS:

-

Ankylosing spondylitis

- ASAS:

-

Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society

- ASDAS:

-

Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score

- axSpA:

-

Axial spondyloarthritis

- BASDAI:

-

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index

- BMP:

-

Bone morphogenetic protein

- COX:

-

Cyclooxygenase

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DKK-1:

-

Dikkopf-1

- DMARD:

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

- ERAP :

-

Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- ILC3:

-

Group 3 innate lymphoid cells

- JAK:

-

Janus kinase

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MAIT:

-

Mucosal-associated invariant T cells

- MIF:

-

Migration inhibition factor

- MMP:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- mSASSS:

-

Modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score

- NF:

-

Nuclear factor

- nr-axSpA:

-

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis

- NSAID:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PDE4:

-

Phosphodiesterase 4

- PDUS:

-

Power Doppler ultrasound

- PGE2:

-

Prostaglandin E2

- Rag :

-

Recombinase activating gene

- RANK:

-

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

- RANKL:

-

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

- RORγt:

-

RAR-related orphan receptor γt

- SpA:

-

Spondyloarthritis

- SPARCC:

-

Spondylitis Research Consortium of Canada

- STAT:

-

Signal transducer and activation of transcription

- sTNF:

-

Soluble tumor necrosis factor

- sTNF-R:

-

Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor

- Th:

-

T-helper

- tmTNF:

-

Transmembrane tumor necrosis factor

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TNFR:

-

Tumor necrosis factor receptor

- TNFR1-TRADD:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-associated death domain

- TNFRSF1A:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-receptor superfamily member type 1A

- Wnt:

-

Wingless protein

References

Ambarus C, Yeremenko N, Tak PP, Baeten D. Pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis: autoimmune or autoinflammatory? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:351–8.

Hreggvidsdottir HS, Noordenbos T, Baeten DL. Inflammatory pathways in spondyloarthritis. Mol Immunol. 2014;57:28–37.

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–83.

Rudwaleit M, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:770–6.

Deodhar A, Strand V, Kay J, Braun J. The term ‘non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis’ is much more important to classify than to diagnose patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:791–4.

Sepriano A, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. Predictive validity of the ASAS classification criteria for axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis after follow-up in the ASAS cohort: a final analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1034–42.

Strand V, Rao SA, Shillington AC, Cifaldi MA, McGuire M, Ruderman EM. Prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis in United States rheumatology practices: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society criteria versus rheumatology expert clinical diagnosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:1299–306.

Dougados M, Baeten D. Spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 2011;377:2127–37.

Jethwa H, Bowness P. The interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 axis in ankylosing spondylitis: new advances and potentials for treatment. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;183:30–6.

Sieper J, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, Boonen A, Zink A. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(Suppl 3):iii8–18.

Landewé R, Braun J, Deodhar A, Dougados M, Maksymowych WP, Mease PJ, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled Phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:39–47.

McGonagle D, Stockwin L, Isaacs J, Emery P. An enthesitis based model for the pathogenesis of spondyloarthropathy. additive effects of microbial adjuvant and biomechanical factors at disease sites. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2155–9.

Watad A, Bridgewood C, Russell T, Marzo-Ortega H, Cuthbert R, McGonagle D. The early phases of ankylosing spondylitis: emerging insights from clinical and basic science. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2668.

Schett G, Lories RJ, D'Agostino MA, Elewaut D, Kirkham B, Soriano ER, et al. Enthesitis: from pathophysiology to treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13:731–41.

Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity. 2017;46:562–76.

Constantinides MG. Interactions between the microbiota and innate and innate-like lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;103:409–19.

Ciccia F, Guggino G, Rizzo A, Saieva L, Peralta S, Giardina A, et al. Type 3 innate lymphoid cells producing IL-17 and IL-22 are expanded in the gut, in the peripheral blood, synovial fluid and bone marrow of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1739–47.

Neerinckx B, Elewaut D, Lories RJ. Spreading spondyloarthritis: are ILCs cytokine shuttles from base camp gut? Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1633–5.

Lausen M, Poulsen TBG, Christiansen G, Kastaniegaard K, Stensballe A, Birkelund S. Proteomic analysis of lipopolysaccharide activated human monocytes. Mol Immunol. 2018;103:257–69.

Ranganathan V, Ciccia F, Zeng F, Sari I, Guggino G, Muralitharan J, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces inflammation and predicts spinal progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:1796–806.

Riechers E, Baerlecken N, Baraliakos X, Achilles-Mehr Bakhsh K, Aries P, Bannert B, et al. Sensitivity and specifity of autoantibodies against CD74 in axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40777 [Epub ahead of print].

Evans DM, Spencer CC, Pointon JJ, Su Z, Harvey D, Kochan G, et al. Interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis implicates peptide handling in the mechanism for HLA-B27 in disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2011;43:761–7.

Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, Lui A, Ermann J, Gensler LS, et al. American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network 2015 recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:282–98.

Smolen JS, Schöls M, Braun J, Dougados M, FitzGerald O, Gladman DD, et al. Treating axial spondyloarthritis and peripheral spondyloarthritis, especially psoriatic arthritis, to target: 2017 update of recommendations by an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:3–17.

Wendling D, Lukas C, Prati C, Claudepierre P, Gossec L, Goupille P, et al. 2018 update of French Society for Rheumatology (SFR) recommendations about the everyday management of patients with spondyloarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85:275–84.

Lockwood MM, Gensler LS. Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31:816–29.

Maseda D, Johnson EM, Nyhoff LE, Baron B, Kojima F, Wilhelm AJ, et al. mPGES1-dependent prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) controls antigen-specific Th17 and Th1 responses by regulating T autocrine and paracrine PGE2 production. J Immunol. 2018;200:725–36.

Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Listing J, Märker-Hermann E, Zeidler H, et al. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on radiographic spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from the German Spondyloarthritis Inception Cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1616–22.

Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Soriano ER, Laura Acosta-Felquer M, Armstrong AW, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1060–71.

Molto A, Granger B, Wendling D, Dougados M, Gossec L. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in early axial spondyloarthritis in daily practice: Data from the DESIR cohort. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:79–82.

Simone D, Nowik M, Gremese E, Ferraccioli GF. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) and combination therapy of conventional DMARD in patients with spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis with axial involvement. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2015;93:65–9.

Lie E, Kristensen LE, Forsblad-d'Elia H, Zverkova-Sandstrom T, Askling J, Jacobsson LT, et al. The effect of comedication with conventional synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs on TNF inhibitor drug survival in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis: results from a nationwide prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:970–8.

Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Sieper J. Open label trial of anakinra in active ankylosing spondylitis over 24 weeks. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:296–8.

Sieper J, Porter-Brown B, Thompson L, Harari O, Dougados M. Assessment of short-term symptomatic efficacy of tocilizumab in ankylosing spondylitis: results of randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:95–100.

Song IH, Heldmann F, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Weiss A, Braun J, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with abatacept: an open-label, 24-week pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1108–10.

Lekpa FK, Farrenq V, Canouï-Poitrine F, Paul M, Chevalier X, Bruckert R, et al. Lack of efficacy of abatacept in axial spondylarthropathies refractory to tumor-necrosis-factor inhibition. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:47–50.

Nocturne G, Dougados M, Constantin A, Richez C, Sellam J, Simon A, et al. Rituximab in the spondyloarthropathies: data of eight patients followed up in the French Autoimmunity and Rituximab (AIR) registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:471–2.

Davis JC Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, Dougados M, Cush J, Clegg DO, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3230–6.

van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, DeWoody K, Williamson P, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:582–91.

Inman RD, Davis JC Jr, Heijde D, Diekman L, Sieper J, Kim SI, et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3402–12.

Baeten D, Baraliakos X, Braun J, Sieper J, Emery P, van der Heijde D, et al. Anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab in treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1705–13.

Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, Baraliakos X, Dougados M, Emery P, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2534–48.

Mitoma H, Horiuchi T, Tsukamoto H, Ueda N. Molecular mechanisms of action of anti-TNF-α agents—comparison among therapeutic TNF-α antagonists. Cytokine. 2018;101:56–63.

Chatzikyriakidou A, Georgiou I, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. The role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and TNF receptor polymorphisms in susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:645–8.

Faustman D, Davis M. TNF receptor 2 pathway: drug target for autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:482–93.

Sveaas SH, Berg IJ, Provan SA, Semb AG, Olsen IC, Ueland T, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines and cytokine receptors in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross-sectional comparative study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44:118–24.

Wendling D, Cedoz JP, Racadot E. Serum and synovial fluid levels of p40 IL12/23 in spondyloarthropathy patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:187–90.

Mei Y, Pan F, Gao J, Ge R, Duan Z, Zeng Z, et al. Increased serum IL-17 and IL-23 in the patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:269–73.

Appel H, Maier R, Bleil J, Hempfing A, Loddenkemper C, Schlichting U, et al. In situ analysis of interleukin-23- and interleukin-12-positive cells in the spine of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1522–9.

Ciccia F, Rizzo A, Triolo G. Subclinical gut inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28:89–96.

Jo S, Koo BS, Lee B, Kwon E, Lee YL, Chung H, et al. A novel role for bone-derived cells in ankylosing spondylitis: focus on IL-23. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491:787–93.

Mortier C, Govindarajan S, Venken K, Elewaut D. It takes “guts” to cause joint inflammation: role of innate-like T cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1489.

Appel H, Maier R, Wu P, Scheer R, Hempfing A, Kayser R, et al. Analysis of IL-17+ cells in facet joints of patients with spondyloarthritis suggests that the innate immune pathway might be of greater relevance than the Th17-mediated adaptive immune response. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R95.

Ciccia F, Accardo-Palumbo A, Alessandro R, Rizzo A, Principe S, Peralta S, et al. Interleukin-22 and interleukin-22-producing NKp44+ natural killer cells in subclinical gut inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1869–78.

Zeng L, Lindstrom MJ, Smith JA. Ankylosing spondylitis macrophage production of higher levels of interleukin-23 in response to lipopolysaccharide without induction of a significant unfolded protein response. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3807–17.

Dong C. TH17 cells in development: an updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:337–48.

Ono T, Okamoto K, Nakashima T, Nitta T, Hori S, Iwakura Y, et al. IL-17-producing γδ T cells enhance bone regeneration. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10928.

Costello ME, Elewaut D, Kenna TJ, Brown MA. Microbes, the gut and ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:214.

Smith JA. The role of the unfolded protein response in axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1425–31.

Gaston JS, Goodall JC, Baeten D. Interleukin-23: a central cytokine in the pathogenesis of spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3668–71.

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Australo-Anglo-American Spondylitis Consortium (TASC), Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, Craddock N, et al. Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1329–37.

Australo-Anglo-American Spondyloarthritis Consortium, Reveille JD, Sims AM, Danoy P, Evans DM, Leo P, et al. Genome-wide association study of ankylosing spondylitis identifies non-MHC susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:123–7.

Lin Z, Bei JX, Shen M, Li Q, Liao Z, Zhang Y, et al. A genome-wide association study in Han Chinese identifies new susceptibility loci for ankylosing spondylitis. Nat Genet. 2011;44:73–7.

Hamersma J, Cardon LR, Bradbury L, Brophy S, van der Horst-Bruinsma I, Calin A, et al. Is disease severity in ankylosing spondylitis genetically determined? Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1396–400.

Brewerton DA, Hart FD, Nicholls A, Caffrey M, James DC, Sturrock RD. Ankylosing spondylitis and HL-A 27. Lancet. 1973;1:904–7.

Schlosstein L, Terasaki PI, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. High association of an HL-A antigen, W27, with ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:704–6.

Dakwar E, Reddy J, Vale FL, Uribe JS. A review of the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E2.

Khan MA. HLA-B27 and its subtypes in world populations. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1995;7:263–9.

Feltkamp TE, Mardjuadi A, Huang F, Chou CT. Spondyloarthropathies in eastern Asia. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:285–90.

Khan MA. Update on spondyloarthropathies. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:896–907.

Reveille JD, Hirsch R, Dillon CF, Carroll MD, Weisman MH. The prevalence of HLA-B27 in the US: data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1407–11.

Khan MA. Thoughts concerning the early diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis and related diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:S6–10.

Mahmoudi M, Aslani S, Nicknam MH, Karami J, Jamshidi AR. New insights toward the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis; genetic variations and epigenetic modifications. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27:198–209.

Tsui FW, Tsui HW, Akram A, Haroon N, Inman RD. The genetic basis of ankylosing spondylitis: new insights into disease pathogenesis. Appl Clin Genet. 2014;7:105–15.

Reveille JD. Biomarkers for diagnosis, monitoring of progression, and treatment responses in ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1009–18.

Fang F, Pan J, Xu L, Li G, Wang J. Identification of potential transcriptomic markers in developing ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis of gene expression profiles. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:826316.

Oppermann U. Why is epigenetics important in understanding the pathogenesis of inflammatory musculoskeletal diseases? Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:209.

Klein K, Gay S. Epigenetics in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:76–82.

Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X, Boehm H, Burgos-Vargas R, Collantes-Estevez E, et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:896–904.

Sepriano A, Regel A, van der Heijde D, Braun J, Baraliakos X, Landewé R, et al. Efficacy and safety of biological and targeted-synthetic DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000396.

Maxwell LJ, Zochling J, Boonen A, Singh JA, Veras MM, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. TNF-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; Issue 4. Art. No.: CD005468: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005468.pub2.

Park JW, Kim MJ, Lee JS, Ha YJ, Park JK, Kang EH, et al. Impact of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor versus nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug treatment on radiographic progression in early ankylosing spondylitis: its relationship to inflammation control during treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:82–90.

Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369:1379–90.

Molnar C, Scherer A, Baraliakos X, de Hooge M, Micheroli R, Exer P, et al. TNF blockers inhibit spinal radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis by reducing disease activity: results from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:63–9.

Toussirot E. Biologics in spondyloarthritis: TNFα inhibitors and other agents. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:669–81.

Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Brown LS, Lavie F, Pangan AL. Early response to adalimumab predicts long-term remission through 5 years of treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:700–6.

van der Heijde D, Breban M, Halter D, DiVittorio G, Bratt J, Cantini F, et al. Maintenance of improvement in spinal mobility, physical function and quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis after 5 years in a clinical trial of adalimumab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1210–9.

Li H, Li Q, Chen X, Ji C, Gu J. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy increased spine and femoral neck bone mineral density of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis with low bone mineral density. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:1413–7.

Milanez FM, Saad CG, Viana VT, Moraes JC, Périco GV, Sampaio-Barros PD, et al. IL-23/Th17 axis is not influenced by TNF-blocking agents in ankylosing spondylitis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:52.

Wang Y, Wang H, Jiang J, Zhao D, Liu Y. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of anti-TNF-alpha therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a mixed-treatments comparison. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:1679–94.

Cosentyx (secukinumab) [prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2018.

Marzo-Ortega H, Sieper J, Kivitz A, Blanco R, Cohen M, Martin R, et al. Secukinumab and sustained improvement in signs and symptoms of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis through two years: results from a phase III study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69:1020–9.

Baraliakos X, Borah B, Braun J, Baeten D, Laurent D, Sieper J, et al. Long-term effects of secukinumab on MRI findings in relation to clinical efficacy in subjects with active ankylosing spondylitis: an observational study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:408–12.

van der Heijde D, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Dougados M, Mease P, Deodhar A, Maksymowych WP, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A antagonist in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis or radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (COAST-V): 16 week results of a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, active-controlled and placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2441–51.

van der Heijde D, Gensler LS, Deodhar A, Baraliakos X, Poddubnyy D, Farmer MK, et al. Dual neutralisation of il-17a and il-17f with bimekizumab in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (AS): 12-week results from a phase 2b, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(Suppl 2):70 Abstract LB0001.

Silacci M, Lembke W, Woods R, Attinger-Toller I, Baenziger-Tobler N, Batey S, et al. Discovery and characterization of COVA322, a clinical-stage bispecific TNF/IL-17A inhibitor for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. MAbs. 2016;8:141–9.

Koenders MI, Marijnissen RJ, Devesa I, Lubberts E, Joosten LA, Roth J, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-interleukin-17 interplay induces S100A8, interleukin-1beta, and matrix metalloproteinases, and drives irreversible cartilage destruction in murine arthritis: rationale for combination treatment during arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2329–39.

Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Sieper J, Clark M, Calderon C, Wang Y, et al. Three multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:258–70.

Baeten D, Østergaard M, Wei JC, Sieper J, Järvinen P, Tam LS, et al. Risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, for ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept, dose-finding phase 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1295–302.

Mease P. Ustekinumab fails to show efficacy in a phase III axial spondyloarthritis program: the importance of negative results. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:179–81.

Al-Mossawi MH, Chen L, Fang H, Ridley A, de Wit J, Yager N, et al. Unique transcriptome signatures and GM-CSF expression in lymphocytes from patients with spondyloarthritis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1510.

Blijdorp ICJ, Menegatti S, van Mens LJJ, van de Sande MGH, Chen S, Hreggvidsdottir HS, et al. Expansion of interleukin-22- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-expressing, but not interleukin-17A-expressing, group 3 innate lymphoid cells in the inflamed joints of patients with spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:392–402.

Raychaudhuri SK, Raychaudhuri SP. Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathways in spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:311–6.

van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, Drescher E, Fleishaker D, Hendrikx T, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1340–7.

Sieper J, Braun J, Kay J, Badalamenti S, Radin AR, Jiao L, et al. Sarilumab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: results of a Phase II, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (ALIGN). Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1051–7.

Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood. 2011;117:3720–32.

Tan AL, Marzo-Ortega H, O'Connor P, Fraser A, Emery P, McGonagle D. Efficacy of anakinra in active ankylosing spondylitis: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1041–5.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of Apremilast to Treat Subjects With Active Ankylosing Spondylitis (POSTURE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01583374. Accessed 7 May 2018.

Lange U, Dischereit G, Neumann E, Frommer K, Tarner IH, Müller-Ladner U. Osteoimmunological aspects on inflammation and bone metabolism. J Rheum Dis Treat. 2015;1:008.

Baum R, Gravallese EM. Bone as a target organ in rheumatic disease: impact on osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:1–15.

Taylan A, Sari I, Akinci B, Bilge S, Kozaci D, Akar S, et al. Biomarkers and cytokines of bone turnover: extensive evaluation in a cohort of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:191.

van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Einstein S, Ory P, Vosse D, Ni L, et al. Radiographic progression of ankylosing spondylitis after up to two years of treatment with etanercept. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1324–31.

Goldring SR. Differential mechanisms of de-regulated bone formation in rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(suppl 2):ii56–60.

van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Baraliakos X, Houben H, van Tubergen A, Williamson P, et al. Radiographic findings following two years of infliximab therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3063–70.

Maksymowych WP, Wichuk S, Chiowchanwisawakit P, Lambert RG, Pedersen SJ. Fat metaplasia and backfill are key intermediaries in the development of sacroiliac joint ankylosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2958–67.

Gengenbacher M, Sebald HJ, Villiger PM, Hofstetter W, Seitz M. Infliximab inhibits bone resorption by circulating osteoclast precursor cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:620–4.

Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, Zwerina J, Ominsky MS, Dwyer D, et al. Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nat Med. 2007;13:156–63.

Fujita K, Janz S. Attenuation of WNT signaling by DKK-1 and -2 regulates BMP2-induced osteoblast differentiation and expression of OPG, RANKL and M-CSF. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:71.

Maksymowych WP. What do biomarkers tell us about the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:101.

Haroon N, Inman RD, Learch TJ, Weisman MH, Lee M, Rahbar MH, et al. The impact of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2645–54.

Li X, Wang J, Liu, H, etal. Inflammation intensity-dependent expression of osteoinductive Wnt proteins is critical for ectopic new bone formation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2018;70:1056–70.

Kim JH, Liu X, Wang J, Chen X, Zhang H, Kim SH, et al. Wnt signaling in bone formation and its therapeutic potential for bone diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5:13–31.

Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, Chao CC, Sathe M, Grein J, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-γt+ CD3+CD4-CD8- entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1069–76.

Eshed I, Bollow M, McGonagle DG, Tan AL, Althoff CE, Asbach P, et al. MRI of enthesitis of the appendicular skeleton in spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1553–9.

Kehl AS, Corr M, Weisman MH. Enthesitis: new insights into pathogenesis, diagnostic modalities, and treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:312–22.

Madsen OR. Stability of fatigue, pain, patient global assessment and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) in spondyloarthropathy patients with stable disease according to the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI). Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:425–32.

Bennett AN, McGonagle D, O'Connor P, Hensor EM, Sivera F, Coates LC, et al. Severity of baseline magnetic resonance imaging-evident sacroiliitis and HLA-B27 status in early inflammatory back pain predict radiographically evident ankylosing spondylitis at eight years. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3413–8.

Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–44.

Rudwaleit M, Khan MA, Sieper J. The challenge of diagnosis and classification in early ankylosing spondylitis: do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1000–8.

Rudwaleit M. New approaches to diagnosis and classification of axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:375–80.

Jans L, Coeman L, Van Praet L, Carron P, Elewaut D, Van den Bosch F, et al. How sensitive and specific are MRI features of sacroiliitis for diagnosis of spondyloarthritis in patients with inflammatory back pain? JBR-BTR. 2014;97:202–5.

Sudoł-Szopińska I, Kwiatkowska B, Włodkowska-Korytkowska M, Matuszewska G, Grochowska E. Diagnostics of sacroiliitis according to ASAS criteria: a comparative evaluation of conventional radiographs and MRI in patients with a clinical suspicion of spondyloarthropathy. Preliminary results. Pol J Radiol. 2015;80:266–76.

Poddubnyy D, Listing J, Sieper J. Brief report: course of active inflammatory and fatty lesions in patients with early axial spondyloarthritis treated with infliximab plus naproxen as compared to naproxen alone: results from the Infliximab As First Line Therapy in Patients with Early Active Axial Spondyloarthritis Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1899–903.

Spadaro A, Iagnocco A, Perrotta FM, Modesti M, Scarno A, Valesini G. Clinical and ultrasonography assessment of peripheral enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:2080–6.

Chu CQ. Molecular probing of TNF: from identification of therapeutic target to guidance of therapy in inflammatory diseases. Cytokine. 2018;101:64–9.

de Vlam K. Soluble and tissue biomarkers in ankylosing spondylitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:671–82.

Turina MC, Yeremenko N, Paramarta JE, De Rycke L, Baeten D. Calprotectin (S100A8/9) as serum biomarker for clinical response in proof-of-concept trials in axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:413.

Wagner C, Visvanathan S, Braun J, van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Hsu B, et al. Serum markers associated with clinical improvement in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with golimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:674–80.

Brandt HC, Spiller I, Song IH, Vahldiek JL, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. Performance of referral recommendations in patients with chronic back pain and suspected axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1479–84.

Malaviya AP, Ostor AJ. Early diagnosis crucial in ankylosing spondylitis. Practitioner. 2011;255:21–4.

Caffrey MF, James DC. Human lymphocyte antigen association in ankylosing spondylitis. Nature. 1973;242:121.

Montserrat V, Galocha B, Marcilla M, Vázquez M, López de Castro JA. HLA-B*2704, an allotype associated with ankylosing spondylitis, is critically dependent on transporter associated with antigen processing and relatively independent of tapasin and immunoproteasome for maturation, surface expression, and T cell recognition: relationship to B*2705 and B*2706. J Immunol. 2006;177:7015–23.

Cipriani A, Rivera S, Hassanhi M, Márquez G, Hernández R, Villalobos C, et al. HLA-B27 subtypes determination in patients with ankylosing spondylitis from Zulia, Venezuela. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:745–9.

Yang T, Duan Z, Wu S, Liu S, Zeng Z, Li G, et al. Association of HLA-B27 genetic polymorphisms with ankylosing spondylitis susceptibility worldwide: a meta-analysis. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:150–61.

Fiorillo MT, Cauli A, Carcassi C, Bitti PP, Vacca A, Passiu G, et al. Two distinctive HLA haplotypes harbor the B27 alleles negatively or positively associated with ankylosing spondylitis in Sardinia: implications for disease pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1385–9.

Khan MA. Polymorphism of HLA-B27: 105 subtypes currently known. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15:362.

Jaakkola E, Herzberg I, Laiho K, Barnardo MC, Pointon JJ, Kauppi M, et al. Finnish HLA studies confirm the increased risk conferred by HLA-B27 homozygosity in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:775–80.

Armas JB, Gonzalez S, Martinez-Borra J, Laranjeira F, Ribeiro E, Correia J, et al. Susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis is independent of the Bw4 and Bw6 epitopes of HLA-B27 alleles. Tissue Antigens. 1999;53:237–43.

Reveille JD. Major histocompatibility genes and ankylosing spondylitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:601–9.

Cortes A, Pulit SL, Leo PJ, Pointon JJ, Robinson PC, Weisman MH, et al. Major histocompatibility complex associations of ankylosing spondylitis are complex and involve further epistasis with ERAP1. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7146.

van Gaalen FA, Verduijn W, Roelen DL, Böhringer S, Huizinga TW, van der Heijde DM, et al. Epistasis between two HLA antigens defines a subset of individuals at a very high risk for ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:974–8.

Corona-Sanchez EG, Muñoz-Valle JF, Gonzalez-Lopez L, Sanchez-Hernandez JD, Vazquez-Del Mercado M, Ontiveros-Mercado H, et al. 383 A/C tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 polymorphism and ankylosing spondylitis in Mexicans: a preliminary study. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2565–8.

Davidson SI, Liu Y, Danoy PA, Wu X, Thomas GP, Jiang L, et al. Association of STAT3 and TNFRSF1A with ankylosing spondylitis in Han Chinese. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:289–92.

Karaderi T, Pointon JJ, Wordsworth TW, Harvey D, Appleton LH, Cohen CJ, et al. Evidence of genetic association between TNFRSF1A encoding the p55 tumour necrosis factor receptor, and ankylosing spondylitis in UK Caucasians. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:110–3.

Pointon JJ, Harvey D, Karaderi T, Appleton LH, Farrar C, Stone MA, et al. The chromosome 16q region associated with ankylosing spondylitis includes the candidate gene tumour necrosis factor receptor type 1-associated death domain (TRADD). Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1243–6.

Hsu H, Xiong J, Goeddel DV. The TNF receptor 1-associated protein TRADD signals cell death and NF-ΚB activation. Cell. 1995;81:495–504.

Danoy P, Pryce K, Hadler J, Bradbury LA, Farrar C, Pointon J, et al. Association of variants at 1q32 and STAT3 with ankylosing spondylitis suggests genetic overlap with Crohn's disease. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001195.

Dong H, Li Q, Zhang Y, Tan W, Jiang Z. IL23R gene confers susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis concomitant with uveitis in a Han Chinese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67505.

International Genetics of Ankylosing Spondylitis Consortium, Cortes A, Hadler J, Pointon JP, Robinson PC, Karaderi T, et al. Identification of multiple risk variants for ankylosing spondylitis through high-density genotyping of immune-related loci. Nat Genet. 2013;45:730–8.

Di Cesare A, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO. The IL-23/Th17 axis in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1339–50.

Zhang L, Fan D, Liu L, Yang T, Ding N, Hu Y, et al. Association study of IL-12B polymorphisms susceptibility with ankylosing spondylitis in mainland han population. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130982.

Wong RH, Wei JC, Huang CH, Lee HS, Chiou SY, Lin SH, et al. Association of IL-12B genetic polymorphism with the susceptibility and disease severity of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:135–40.

Chen C, Zhang X, Wang Y. Analysis of JAK2 and STAT3 polymorphisms in patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Chinese Han population. Clin Immunol. 2010;136:442–6.

Reeves E, Colebatch-Bourn A, Elliott T, Edwards CJ, James E. Functionally distinct ERAP1 allotype combinations distinguish individuals with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:17594–9.

Abdullah H, Zhang Z, Yee K, Haroon N. KIR3DL1 interaction with HLA-B27 is altered by ankylosing spondylitis associated ERAP1 and enhanced by MHC class I cross-linking. Discov Med. 2015;20:79–89.

Chen L, Ridley A, Hammitzsch A, Al-Mossawi MH, Bunting H, Georgiadis D, et al. Silencing or inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1) suppresses free heavy chain expression and Th17 responses in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:916–23.

Bang SY, Kim TH, Lee B, Kwon E, Choi SH, Lee KS, et al. Genetic studies of ankylosing spondylitis in Koreans confirm associations with ERAP1 and 2p15 reported in white patients. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:322–4.

Brown MA, Kenna T, Wordsworth BP. Genetics of ankylosing spondylitis—insights into pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:81–91.

Ma X, Liu Y, Zhang H, Qiu R, Zhao H, Xin Q, et al. Evidence for genetic association of CARD9 and SNAPC4 with ankylosing spondylitis in a Chinese Han population. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:318–24.

Zvyagin IV, Mamedov IZ, Britanova OV, Staroverov DB, Nasonov EL, Bochkova AG, et al. Contribution of functional KIR3DL1 to ankylosing spondylitis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7:471–6.

Humira (adalimumab) [prescribing information]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie, Inc.; 2017.

Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Mease PJ, Maksymowych WP, Brown MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial (ABILITY-1). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:815–22.

Cimzia (certolizumab pegol) [prescribing information]. Smyrna, GA, USA: UCB, Inc.; 2019.

Enbrel (etanercept) [prescribing information]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Immunex Corporation; 2017.

Simponi (golimumab) [prescribing information]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.; 2018.

Remicade (infliximab) [prescribing information]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.; 2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. David Yu for his critical review of this manuscript.

Funding

Technical assistance with editing, figure preparation, and styling of the manuscript for submission was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc. and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions and received no financial support or other form of compensation related to the development of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conceptualization of the manuscript, critically revised the drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

DF has received grant/research support from Amgen, BMS, Novartis, NIH, Pfizer, and Roche/Genentech and has been a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Cytori, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, and UCB. He has also served on Speakers’ Bureaus (CME ONLY) for BMS and Actelion. JL has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Genentech, and Novartis and as a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, and Pfizer.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Furst, D.E., Louie, J.S. Targeting inflammatory pathways in axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 21, 135 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1885-z

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1885-z