Abstract

Background

In addition to anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs), antibodies targeting carbamylated (i.e., homocitrullinated) proteins (anti-CarP antibodies) have been described in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, the extent to which anti-CarP antibodies are truly distinct from ACPA remains unclear, and few studies have focused on specific autoantigens. Here, we examine cross-reactivity between ACPA and anti-CarP antibodies, in the context of the candidate autoantigen α-enolase.

Methods

Cross-reactivity was examined by immunoblotting of citrullinated and carbamylated proteins using purified ACPA; and by peptide absorption experiments, using the citrullinated α-enolase peptide CEP-1 and a homocitrulline-containing version (carb-CEP-1) in ELISA. The population-based case-control cohort EIRA (n = 2836 RA; 373 controls) was screened for reactivity with CEP-1 and carb-CEP-1, using the ISAC multiplex array. Associations between anti-CarP antibodies, smoking and genetic risk factors were analysed using unconditional logistic regression models. Differences in antibody levels were investigated using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Affinity-purified ACPA was found to bind carbamylated proteins and homocitrulline-containing peptides, demonstrating definitive cross-reactivity between ACPA and anti-CarP antibodies. Anti-carb-CEP-1 reactivity in EIRA was almost exclusively confined to the CEP-1-positive subset, and this group of RA patients (21 %) displayed a particularly strong ACPA response with marked epitope spreading. The small RA subset (3 %) with homocitrulline reactivity in the absence of citrulline reactivity did not associate with smoking or risk genes, and importantly had significantly lower anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody levels.

Conclusion

Our data presented herein cast doubt on the specificity of anti-CarP antibodies in RA, which we posit may be a subset of cross-reactive ACPA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Autoantibodies to citrullinated proteins (ACPA) are today a well-known and accepted feature of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1, 2]. These autoantibodies have been linked to RA risk factors, most notably HLA-DRB1 shared epitope (SE) alleles and cigarette smoking, and their presence predicts a more destructive disease process [3–7]. However, despite the identification of several putative citrullinated autoantigens, including fibrinogen [8], vimentin [9], type II collagen [10], α-enolase [11] and histone 4 [12], the specific in vivo ACPA targets triggering autoimmunity and driving disease remain obscure.

More recently, antibodies to carbamylated proteins containing homocitrulline (anti-CarP antibodies) were described in RA [13]. Protein carbamylation, or homocitrullination, is an enzyme-independent post-translational modification of lysine residues by isocyanate, present in, for example, cigarette smoke [14]. As smoking is a well-described risk factor for RA [15, 16], it has been proposed that smoking could be linked to anti-CarP antibodies in RA via increased carbamylation and the subsequent production of anti-CarP antibodies [17–19]. However, scientific data in support of this hypothesis has yet to be presented. Anti-CarP antibodies are specific for RA [20] and reportedly distinct from ACPA, based on the detection of anti-CarP antibodies in ACPA-negative disease [13, 21, 22]. However, in the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of RA (EIRA) study and in the Dutch Early Arthritis Clinic (EAC) cohort, we recently showed that only 4–7 % of RA patients were anti-CarP antibody-positive in the absence of ACPA. Notably, there was no specific association between HLA-DRB1 SE or smoking and anti-CarP antibodies, when the analyses were adjusted for the presence of ACPA [21].

In addition, the widely used biochemical assay for detection of peptidylcitrulline, the so-called Senshu method [23] where rabbit polyclonal antibodies bind chemically modified citrulline residues, was found to also detect homocitrulline [24] and purified ACPA have been shown to bind not only citrullinated fibrinogen, but also carbamylated fibrinogen [20].

The extent to which these two autoantibody specificities are cross-reactive, and the association between these antibodies and environmental and genetic risk factors for RA, has not been thoroughly explored, and as yet, only fibrinogen and more recently vimentin have been studied in this context [13, 20, 21, 24–26]. Therefore, it is imperative that more work on specific antigens is performed in order to fully understand the relationship between ACPA and anti-CarP antibodies in the aetiopathology of RA [19].

Citrullinated α-enolase has long been scrutinized as a potential target for ACPA in RA [11, 27–34]. Antibodies to CEP-1, the immunodominant B cell epitope of citrullinated α-enolase [27] are found in approximately 40 % of patients with RA, and have been associated with SE, PTPN22 and smoking [28, 32]. Hence, in the present study, we have investigated the antibody responses to citrullinated and carbamylated α-enolase and their relation to RA risk factors in the Swedish population-based case-control cohort EIRA.

Methods

Patients

The present study includes patients newly diagnosed with RA (cases) and age-matched, sex-matched and residential area-matched controls from the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of RA (EIRA) cohort. Information on cigarette smoking (“ever smoker” or “never smoker”) was obtained via self-reported questionnaire at baseline [16]. Genotyping of HLA-DRB1 shared epitope (SE) alleles and the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene (PTPN22 rs2476601) was performed on blood samples obtained within one week of the RA diagnosis [5, 35]. Smoking and genetic data for the present study were retrieved from the EIRA database on 2784, 2235 and 2477 patients with RA and 4864, 1923 and 1936 controls, for smoking, SE and PTPN22, respectively. For antibody purification, plasma samples from patients with RA with a strong anti-CEP-1 antibody response (n = 5) or a strong anti-CCP2 antibody response (n = 38) were collected at the Rheumatology Clinic, Karolinska University Hospital Solna, Stockholm, Sweden. Informed consent was obtained from participating patients and controls, and ethical approvals for the study was granted at the regional ethics review board at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Antigens

Three cyclic peptides corresponding to amino acid 5-21 of full-length α-enolase were synthesized by Innovagen (Malmö, Sweden): the original CEP-1 peptide containing two citrulline residues (CEP-1) [27]; the arginine-containing control peptide REP-1; and a version of CEP-1 containing homocitrulline in the place of citrulline, denoted carb-CEP-1 (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Recombinant human α-enolase, produced in-house, and purified human fibrinogen (Enzyme Research, South Bend, IN, USA) depleted of immunoglobulins, were citrullinated or carbamylated in vitro. Citrullination was performed for 2 h at 37 °C, at a protein concentration of 1 mg/ml, in peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) buffer (100 mM Tris, 10 mM CaCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.6) using 2 U/mg of rabbit skeletal muscle PAD2 enzyme (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), followed by extensive dialysis to calcium-free PBS. Carbamylated proteins were produced by incubating α-enolase and fibrinogen in PBS at 1 mg/ml in the presence of 100 mM potassium cyanate (KOCN) (Sigma) overnight at 37 °C, followed by extensive dialysis to calcium-free PBS. Successful citrullination and carbamylation were confirmed by mass spectrometry (data not shown). For a detailed description of the mass spectrometry analysis see Additional file 1: Supplementary methods.

Affinity purification of ACPA IgG

Plasma samples (n = 43) were centrifuged and diluted in PBS (1:5 v/v) before applied to Protein G HP columns (GE Healthcare) for whole IgG enrichment. To further purify CEP-1-specific IgG, REP-1 and CEP-1 peptides (1 mg/ml) were directly coupled to 1 ml NHS-Sepharose columns (GE Healthcare), and anti-CEP-1 IgG from five anti-CEP-1 antibody-positive serum samples was subsequently purified from whole IgG using the CEP-1 affinity column, after pre-absorption on the REP-1 column to remove non-citrulline-specific antibodies. Bound antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.7) and directly neutralized with 1 M Tris (pH 9). Column flow-through (FT) fractions depleted of anti-CEP-1 IgG were collected in parallel. MicrosepTM UF Centrifugal Devices (Pall Life Science, Port Washington, NY, USA) were used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, to concentrate the antibodies and to change the buffer into PBS. Anti-CCP2-reactive IgG from 38 anti-CCP2-positive RA serum samples were pooled after purification on CCP2-columns kindly donated by EuroDiagnostica AB, Malmö, Sweden, as previously described [36].

Antibody detection using ISAC and ELISA

High-throughput anti-CEP-1, anti-REP-1 and anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody screening of serum samples from 2836 patients with RA from the EIRA cohort and 373 EIRA controls was accomplished using a custom-made microarray based on the ImmunoCAP immuno solid-phase allergen chip multiplex assay (ISAC) microarray system (Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden) containing the peptides of interest, as previously described [25, 37]. This microarray also contains a large number of other citrullinated peptides derived from different proteins, including fibrinogen, vimentin and collagen type II, and their corresponding arginine-containing control peptides. Cut offs for antibody positivity were calculated based on the 98th percentile among the EIRA controls. A detailed description of the ISAC method is provided in Additional file 1.

For testing the reactivity of the affinity-purified anti-CEP-1 and FT IgG fractions, and for analysing the degree of cross-reactivity between double-positive (CEP-1+/Carb-CEP-1+) or single-positive (CEP-1+/Carb-CEP-1- and CEP-1-/Carb-CEP-1+) EIRA RA serum samples, peptide ELISAs detecting anti-CEP-1 and anti-Carb-CEP-1 IgG were used as previously described [27, 28, 32] (see Additional file 1: Supplementary methods for details).

Cross-reactivity assay

Anti-CEP-1/anti-Carb-CEP-1 double-positive serum samples (n = 4), anti-CEP-1 single-positive (n = 4), and anti-Carb-CEP-1 single-positive serum samples (n = 4) were selected for the cross-reactivity experiment. Serum samples were diluted 1:100 in radioimmunoassay (RIA) buffer and incubated with 100 μg/ml of the CEP-1 or the Carb-CEP-1 peptide for 2 h at room temperature (RT). Following incubation, the absorbed serum was analysed using the same protocol as for the peptide ELISA described previously (see also Additional file 1).

Western blot

Citrullinated, carbamylated and unmodified proteins (100 ng/well) were separated on NuPAGE® Bis-Tris 4-20 % gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5 % milk in Tris-buffered saline/0.05 % Tween and probed with a pool (n = 38) of purified anti-CCP2 IgG (or the corresponding CCP2 column FT IgG pool) at 2 μg/ml overnight at 4 °C, then washed with PBS/0.05 % Tween and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA), diluted 1:10,000, for 1 h at RT. Bound antibody was detected using ECL chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

Statistics

Patients were divided into four different subsets according to the presence or absence of anti-CEP-1 and anti-carb-CEP-1 IgG. The odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for each RA subset, in relation to smoking, SE and PTPN22, were calculated separately through unconditional logistic regression models, adjusted for matching variables (age, gender and residential area). Exposed individuals were compared with unexposed individuals (smokers vs. non-smokers, carriers of any copy of SE vs. non-carriers, carriers of the PTPN22 risk allele vs. non-carriers). All analyses were implemented through SAS V.9.3. Statistical differences in antibody levels and number of ACPA fine specificities, between different subsets, were determined by the Mann-Whitney U test for independent groups. The same method was also used to determine the relationship between anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody levels and SE/smoking.

Results

Purified ACPA IgG bind carbamylated proteins

Using a pool of affinity-purified anti-CCP2 IgG, previously described to bind both citrullinated α-enolase and fibrinogen [36], we could demonstrate cross-reactivity of human ACPA with carbamylated α-enolase for the first time, and in line with previous reports [20, 24], we could also show cross-reactivity with carbamylated fibrinogen (Fig. 1a). There was no reactivity against unmodified proteins. The corresponding FT IgG pool bound neither modified nor native proteins; only some weak unspecific background staining was observed.

Human anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) cross-react with carbamylated epitopes. a Native (n), in vitro citrullinated (Cit) and in vitro carbamylated (Carb) samples of recombinant human α-enolase and purified human fibrinogen were subjected to western blot using affinity-purified anti-CCP2 IgG (ACPA IgG) and CCP2-depleted column flow-through IgG (FT IgG), obtained from a pool of 38 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) serum samples. b Affinity-purified anti-CEP-1 IgG and the corresponding column FT IgG fractions from five patients with RA were tested for reactivity to the carb-CEP-1 peptide in ELISA; antibody levels are presented as optical density (OD)

Purified anti-CEP-1 IgG displays cross-reactivity with a homocitulline-containing version of CEP-1

To further investigate the specificity and extent of cross-reactivity between citrullinated and carbamylated epitopes, we focused on α-enolase and the immunodominant CEP-1 epitope. Affinity-purified anti-CEP-1-specific IgG bound not only CEP-1 in ELISA, but also a version of CEP-1 (denoted carb-CEP-1) identical in sequence but with citrulline residues replaced with homocitrullines. Anti-CEP-1 IgG purified from different patients with RA showed consistently strong binding to the CEP-1 peptide in ELISA (data not shown), and in addition displayed varying degrees of binding to the carb-CEP-1 peptide (Fig. 1b). Flow-through IgG from the same five patients did not bind to CEP-1 or carb-CEP-1, demonstrating that the carb-CEP-1 reactivity was confined to the anti-CEP-1 IgG eluate fraction. None of the anti-CEP-1 IgG column eluates demonstrated reactivity to the control peptide REP-1 (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that citrullinated α-enolase-specific ACPA also have the ability to bind homocitrulline-containing epitopes.

Anti-carb-CEP-1 reactivity in relation to anti-CEP-1 status in EIRA

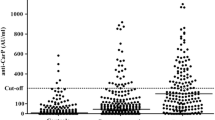

Using the large EIRA case-control cohort, we next sought to determine the proportion of patients with RA with antibodies binding to carb-CEP-1, and how this reactivity correlated with CEP-1 positivity. Reactivity to CEP-1, REP-1 and carb-CEP-1 was therefore analysed in serum from 2836 RA cases using the ISAC platform. The frequency of anti-CEP-1 antibody-positive patients with RA was 41 %, which is in accordance with previous analyses using a smaller proportion of EIRA (n = 1985 RA cases) and the ELISA method [28, 32]. There was less than 2 % reactivity towards the REP-1 control peptide, while 21 % of patients with RA had reactivity towards the carb-CEP-1 peptide (Fig. 2a). Notably, almost all patients positive for anti-carb-CEP-1 IgG were also positive for antibodies to CEP-1. Only 3 % of EIRA RA serum samples had a unique and specific reactivity with carb-CEP-1. Importantly, anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody levels were significantly lower in patients who were carb-CEP-1 single-positive than in the CEP-1/carb-CEP-1 double-positive RA subset (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, when increasing specificity to 100 %, the carb-CEP-1 single-positive subset was almost completely eliminated (<1 %) while the double-positive subset remained (data not shown), suggesting that carb-CEP-1 reactivity in the absence of CEP-1 reactivity is extremely rare.

Reactivity to CEP-1 and homocitrullinated CEP-1 peptide (carb-CEP-1) in Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (EIRA) rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cases. a Sera from 2836 patients with RA from the EIRA cohort were tested for reactivity with CEP-1 and carb-CEP-1 using the immuno solid-phase allergen chip multiplex assay (ISAC) platform and divided into subsets. b Anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody levels were compared between the CEP-1+/carb-CEP-1+ and CEP-1-/carb-CEP-1+ subsets. Antibody levels are presented as arbitrary units (AU)

Cross-reactivity between CEP-1 and carb-CEP-1

In order to more directly determine whether the anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody response was simply the result of homocitrulline-cross-reactive anti-CEP-1 antibodies, we subsequently performed peptide absorption experiments. In these experiments we demonstrated that ACPA from different patients with RA displayed varying degrees of cross-reactivity to the homocitrulline-containing CEP-1 homologue, carb-CEP-1. In a selection of 16 RA serum samples, we examined whether the CEP-1 peptide and/or the carb-CEP-1 peptide could inhibit antibody binding to CEP-1 and/or carb-CEP. Not surprisingly, in CEP-1 positive sera, pre-incubation with the CEP-1 peptide completely inhibited (100 %) all CEP-1 reactivity, while inhibition with the carb-CEP-1 peptide was less efficient (4–49 %) in blocking binding to CEP-1 (Fig. 3a). Notably, the anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody response in double-positive sera was blocked efficiently by both CEP-1 and carb-CEP-1 pre-incubation, while in the rare group of carb-CEP-1 single-positive subjects, more varying degrees of inhibition was seen (Fig. 3b). Two serum samples had almost complete inhibition of binding to carb-CEP-1 after both CEP-1 and carb-CEP-1 pre-incubation, while the CEP-1 peptide did not inhibit binding to carb-CEP-1 in the two serum samples that displayed a very strong anti-carb-CEP-1 IgG response (optical density (OD) values >3.5 AU/ml).

Homocitrullinated CEP-1 peptide (Carb-CEP-1) reactivity results from cross-reactive anti-CEP-1 antibodies. To assess cross-reactivity between CEP-1 and carb-CEP-1, serum from patients positive for either anti-CEP-1 antibodies only (n = 4) or for anti-carb-CEP-1 antibodies only (n = 4), and serum from patients positive for both anti-CEP-1 and anti-carb-CEP-1 antibodies (n = 4), were pre-absorbed by incubating with either dilution buffer, CEP-1 peptide or carb-CEP-1 peptide. Levels of anti-CEP-1 (a) and anti-carb-CEP-1 (b) antibodies were subsequently measured by ELISA, and presented as optical density (OD). EIRA Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis cohort

Anti-carb-CEP-1 reactivity in relation to smoking in EIRA

Based on the link between smoking and carbamylation and the association between smoking and RA [14–16], we next investigated the role of smoking in the development of anti-carb-CEP-1 antibodies. Our first analysis showed that smoking was associated with anti-carb-CEP-1 positivity, and with elevated anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody levels (data not shown). However, we have previously shown that smoking is strongly associated with anti-CEP-1 antibodies [28, 32], and as the majority of anti-carb-CEP-1 reactivity was confined to the CEP-1-positive subset, we also had to consider CEP-1 reactivity in the analysis. Hence, we divided the patients with RA into four subsets, based on presence or absence of carb-CEP-1 and/or CEP-1 reactivity. With this division, we found that smoking was significantly associated with anti-CEP-1 single-positive RA, with an odds ratio of 2.21 (95 % CI 1.82, 2.68), and with CEP-1/carb-CEP-1 double-positive disease (OR = 2.6; 95 % CI 2.07, 3.25), but not with anti-carb-CEP-1 single-positive disease (OR = 1.15; 95 % CI 0.71, 1.86) (Table 1). Importantly, there was no statistical difference when comparing ORs for the double-positive vs. the CEP-1 single-positive subset (2.6 vs. 2.21, p = 0.37), suggesting that smoking has no specific effect on the development of anti-CarP antibodies, in line with our previous data [21].

Anti-carb-CEP-1 reactivity in relation to HLA-DRB1 SE in EIRA

A similar analysis to that used for smoking was also performed for HLA-DRB1 SE, and again there was significant association between HLA-DRB1 SE and both anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody positivity and elevated anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody levels (data not shown). When subdividing patients, the association with the SE was significantly stronger in CEP-1 single-positive RA (OR = 6.58; 95 % CI 5.01, 8.65) than with carb-CEP-1 single-positive RA (OR = 2.07; 95 % CI 1.19, 3.61), (6.58 vs. 2.07, p = 0.0002) (Table 2). However, contrary to the smoking data, the association between the SE and the double-positive subset (OR = 10.42; 95 % CI 7.2, -14.90) was significantly stronger than with the CEP-1 single-positive subset (10.42 vs. 6.58, p = 0.03), suggesting an SE-mediated effect on the development of carb-(cross)-reactive antibodies.

Anti-carb-CEP-1 reactivity in relation to PTPN22 in EIRA

We also investigated the association of PTPN22 polymorphism with the presence of anti-carb-CEP-1 antibodies, in relation to the anti-CEP-1 antibody response. PTPN22 differed from smoking and SE, in the sense that there was no difference in the association between CEP-1 single-positive (OR = 1.90; 95 % CI 1.54, 2.35) and carb-CEP-1 single-positive (OR = 2.05; 95 % CI 1.19, 3.51) disease (1.90 vs. 2.05, p = 0.85), and having both antibody reactivities (OR = 2.07; 95 % CI 1.64, 2.6) did not significantly alter the association either (1.90 vs. 2.07, p = 0.73) (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Anti-carb-CEP-1 reactivity in relation to the overall ACPA response in EIRA

Finally we analysed anti-CEP-1 IgG levels, anti-CCP2 IgG levels, and the number of ACPA fine specificities in CEP-1 single-positive RA, compared to CEP-1/carb-CEP-1 double-positive RA. Higher anti-CEP-1 and anti-CCP2 IgG levels were detected in the double-positive subset, and a higher number of ACPA fine specificities were recorded in CEP-1/carb-CEP-1 double-positive patients with RA, compared to CEP-1 single-positive patients; all values were significant with p values <0.0001 (Fig. 4). These results clearly demonstrate a stronger anti-CEP-1 antibody response and a stronger overall ACPA response in the subset with carb-CEP-1 (cross)-reactive antibodies.

The anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) response is stronger in CEP-1/homocitrullinated CEP-1 peptide (carb-CEP-1) double-positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) than in CEP-1 single-positive RA. Anti-CEP-1 IgG (a), anti-CCP2 IgG (b), and the number of ACPA fine specificities (c) were compared between the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (EIRA) cohort RA CEP-1+/carb-CEP-1- and CEP-1+/carb-CEP-1+ subsets (****p < 0.0001). Data in a and c were generated using the immuno solid-phase allergen chip multiplex assay (ISAC) microarray; data in b were generated by ELISA. AU arbitrary units

Discussion

This is the first report of an antibody response to carbamylated α-enolase in RA. Previous reports on anti-CarP antibodies in RA have focused mainly on carbamylated fibrinogen or the complex protein mixture of carbamylated fetal calf serum [13, 20–22, 24, 25], and recently a report was published on antibodies against carbamylated vimentin (26). Our study suggests that the anti-CarP antibody response in RA can be explained by cross-reactive ACPA. This conclusion was particularly evident from immunoblotting experiments using affinity-purified anti-CCP2 IgG molecules. Purified ACPA bound not only citrullinated α-enolase and citrullinated fibrinogen, but also carbamylated α-enolase and -fibrinogen, while unmodified proteins were not targeted, and importantly, ACPA-depleted IgG was not able to recognize citrullinated or carbamylated epitopes. Notably, the two earliest reports linking carbamylation to the development of arthritis in mouse models already describe cross-reactivity between citrulline- and homocitrulline-containing epitopes [17, 18].

Using a synthetic and artificial peptide based on the well-characterised CEP-1 epitope from citrullinated α-enolase [27, 28, 32] but with homocitrulline in place of citrulline (amino acids 9 and 15), we showed that approximately 20 % of patients with RA in the EIRA cohort had antibodies to carb-CEP-1. While the carb-CEP-1 peptide most likely does not represent an in vivo antigenic target (amino acid 9 and 15 of unmodified α-enolase are arginines, not lysines), and any biological and mechanistic implications based on the peptide data therefore are limited, the observed cross-reactivity between anti-CEP-1 IgG and carb-CEP-1 suggests that antibodies to citrullinated α-enolase can also bind to homocitrulline-containing epitopes. The fact that the anti-carb-CEP-1 antibody-positive subset of patients was almost exclusively confined to the CEP-1-positive population, together with the observation that CEP-1 could block carb-CEP-1 reactivity much more efficiently than carb-CEP-1 could block CEP-1 reactivity, clearly supports our interpretation; that is, that the reactivity measured as anti-CarP-antibodies are for the most part represented by cross-reactive ACPA.

The group of patients with anti-carb-CEP-1 antibodies had higher anti-CEP-1 antibody levels, but also higher anti-CCP2 antibody levels, and a broader ACPA repertoire (than anti-CEP-1 antibody-positive patients without anti-carb-CEP-1 antibodies), suggesting a stronger ACPA response in general in this group of patients, with epitope spreading and more promiscuous antigen-recognition, i.e., also including epitopes containing homocitrulline, which is structurally very similar to citrulline. Our gene-environment association data suggest that this extended antibody reactivity is influenced by HLA-DRB1 SE alleles, but not by PTPN22 or smoking.

Recently, anti-CarP antibodies have also been described in small subsets of patients with non-RA early arthritis [38], and in a large portion of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome [39], where the presence of anti-CarP antibodies correlated with disease severity. Contrary to our conclusion, these reports seem to indicate that this class of autoantibodies could be more of a general marker for inflammation than cross-reactive ACPAs, which would be specific for RA.

Taken together, our data seem to suggest that cross-reactivity between ACPA and anti-CarP antibodies in RA is a common phenomenon. Here, we have described this cross-reactivity in the context of the RA candidate autoantigen α-enolase. However, supported by recent work from Scinocca and colleagues, demonstrating cross-reactivity between citrullinated and carbamylated fibrinogen [20], we posit that this is also likely the case for other citrullinated/carbamylated antigens. In line with previous reports [20, 24], this cross-reactivity is not complete or consistent, and indeed a small percentage (3 %) of RA cases in our study demonstrated reactivity exclusively to the carb-CEP-1 peptide and not CEP-1. However, this subset of patients was almost completely eliminated when using a more stringent cut off for positivity, casting doubt on the existence of specific anti-CarP antibodies.

Conclusions

ACPAs are cross-reactive with homocitrullinated epitopes on α-enolase. This calls into question the specificity of anti-carP antibodies, which we posit may be a cross-reactive subset of ACPAs.

Abbreviations

- ACPA:

-

anti-citrullinated protein antibody

- anti-CarP:

-

anti-carbamylated protein antibody

- carb-CEP-1:

-

homocitrullinated CEP-1 peptide

- CCP2:

-

anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, second generation

- CEP-1:

-

the immunodominant peptide epitope of citrullinated alpha-enolase

- EIRA:

-

Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis cohort

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FT:

-

flow-through

- HLA-DRB1:

-

HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, DRB1-9 beta chain

- IgG:

-

immunoglobulin G

- ISAC:

-

immuno solid-phase allergen chip multiplex assay

- OD:

-

optical density

- PAD:

-

peptidylarginine deiminase

- PTPN22:

-

protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 22 (lymphoid)

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- RT:

-

room temperature

- SE:

-

shared epitope risk alleles

References

Girbal-Neuhauser E, Durieux JJ, Arnaud M, Dalbon P, Sebbag M, Vincent C, et al. The epitopes targeted by the rheumatoid arthritis-associated antifilaggrin autoantibodies are posttranslationally generated on various sites of (pro)filaggrin by deimination of arginine residues. J Immunol. 1999;162:585–94.

Kay J, Upchurch KS. ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51 Suppl 6:vi5–9.

Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K, Källberg H, Bengtsson C, Grunewald J, et al. A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:38–46.

Huizinga TWJ, Amos CI, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, Chen W, van Gaalen FA, Jawaheer D, et al. Refining the complex rheumatoid arthritis phenotype based on specificity of the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope for antibodies to citrullinated proteins. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3433–8.

Källberg H, Padyukov L, Plenge RM, Rönnelid J, Gregersen PK, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, et al. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions involving HLA-DRB1, PTPN22, and smoking in two subsets of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:867–75.

Linn-Rasker SP, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, van Gaalen FA, Kloppenburg M, de Vries RRP, le Cessie S, et al. Smoking is a risk factor for anti-CCP antibodies only in rheumatoid arthritis patients who carry HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:366–71.

Avouac J, Gossec L, Dougados M. Diagnostic and predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:845–51.

Masson-Bessière C, Sebbag M, Girbal-Neuhauser E, Nogueira L, Vincent C, Senshu T, et al. The major synovial targets of the rheumatoid arthritis-specific antifilaggrin autoantibodies are deiminated forms of the alpha- and beta-chains of fibrin. J Immunol. 2001;166:4177–84.

Vossenaar ER, Després N, Lapointe E, van der Heijden A, Lora M, Senshu T, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis specific anti-Sa antibodies target citrullinated vimentin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R142–50.

Burkhardt H, Sehnert B, Bockermann R, Engström A, Kalden JR, Holmdahl R. Humoral immune response to citrullinated collagen type II determinants in early rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1643–52.

Kinloch A, Tatzer V, Wait R, Peston D, Lundberg K, Donatien P, et al. Identification of citrullinated alpha-enolase as a candidate autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1421–9.

Pratesi F, Dioni I, Tommasi C, Alcaro MC, Paolini I, Barbetti F, et al. Antibodies from patients with rheumatoid arthritis target citrullinated histone 4 contained in neutrophils extracellular traps. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1414–22.

Shi J, Knevel R, Suwannalai P, van der Linden MP, Janssen GMC, van Veelen PA, et al. Autoantibodies recognizing carbamylated proteins are present in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and predict joint damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17372–7.

Wang Z, Nicholls SJ, Rodriguez ER, Kummu O, Hörkkö S, Barnard J, et al. Protein carbamylation links inflammation, smoking, uremia and atherogenesis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1176–84.

Vessey MP, Villard-Mackintosh L, Yeates D. Oral contraceptives, cigarette smoking and other factors in relation to arthritis. Contraception. 1987;35:457–64.

Stolt P, Bengtsson C, Nordmark B, Lindblad S, Lundberg I, Klareskog L, et al. Quantification of the influence of cigarette smoking on rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population based case-control study, using incident cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:835–41.

Mydel P, Wang Z, Brisslert M, Hellvard A, Dahlberg LE, Hazen SL, et al. Carbamylation-dependent activation of T cells: a novel mechanism in the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis. J Immunol. 2010;184:6882–90.

Turunen S, Koivula M-K, Risteli L, Risteli J. Anticitrulline antibodies can be caused by homocitrulline-containing proteins in rabbits. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3345–52.

Feist E, Steiner G. Rheumatoid arthritis: an antigenic chameleon. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1753–4.

Scinocca M, Bell DA, Racapé M, Joseph R, Shaw G, McCormick JK, et al. Antihomocitrullinated fibrinogen antibodies are specific to rheumatoid arthritis and frequently bind citrullinated proteins/peptides. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:270–9.

Jiang X, Trouw LA, van Wesemael TJ, Shi J, Bengtsson C, Källberg H, et al. Anti-CarP antibodies in two large cohorts of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their relationship to genetic risk factors, cigarette smoking and other autoantibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1761–8.

Shi J, van de Stadt LA, Levarht EWN, Huizinga TWJ, Hamann D, van Schaardenburg D, et al. Anti-carbamylated protein (anti-CarP) antibodies precede the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:780–3.

Senshu T, Sato T, Inoue T, Akiyama K, Asaga H. Detection of citrulline residues in deiminated proteins on polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Anal Biochem. 1992;203:94–100.

Shi J, Willemze A, Janssen GMC, van Veelen PA, Drijfhout JW, Cerami A, et al. Recognition of citrullinated and carbamylated proteins by human antibodies: specificity, cross-reactivity and the “AMC-Senshu” method. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:148–50.

Brink M, Verheul MK, Rönnelid J, Berglin E, Holmdahl R, Toes REM, et al. Anti-carbamylated protein antibodies in the pre-symptomatic phase of rheumatoid arthritis, their relationship with multiple anti-citrulline peptide antibodies and association with radiological damage. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:25.

Juarez M, Bang H, Hammar F, Reimer U, Dyke B, Sahbudin I, Buckley CD, Fisher B, Filer A, Raza K. Identification of novel antiacetylated vimentin antibodies in patients with early inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015.

Lundberg K, Kinloch A, Fisher BA, Wegner N, Wait R, Charles P, et al. Antibodies to citrullinated alpha-enolase peptide 1 are specific for rheumatoid arthritis and cross-react with bacterial enolase. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3009–19.

Mahdi H, Fisher BA, Källberg H, Plant D, Malmström V, Rönnelid J, et al. Specific interaction between genotype, smoking and autoimmunity to citrullinated alpha-enolase in the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1324.

Goëb V, Thomas-L'Otellier M, Daveau R, Charlionet R, Fardellone P, Le Loët X, et al. Candidate autoantigens identified by mass spectrometry in early rheumatoid arthritis are chaperones and citrullinated glycolytic enzymes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R38.

van de Stadt LA, van der Horst AR, de Koning MHMT, Bos WH, Wolbink GJ, van de Stadt RJ, et al. The extent of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody repertoire is associated with arthritis development in patients with seropositive arthralgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:128–33.

Fisher BA, Plant D, Brode M, van Vollenhoven RF, Mathsson L, Symmons D, et al. Antibodies to citrullinated α-enolase peptide 1 and clinical and radiological outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1095–8.

Lundberg K, Bengtsson C, Kharlamova N, Reed E, Jiang X, Källberg H, et al. Genetic and environmental determinants for disease risk in subsets of rheumatoid arthritis defined by the anticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody fine specificity profile. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:652–8.

Amara K, Steen J, Murray F, Morbach H, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Joshua V, et al. Monoclonal IgG antibodies generated from joint-derived B cells of RA patients have a strong bias toward citrullinated autoantigen recognition. J Exp Med. 2013;210:445–55.

Tan Y-C, Kongpachith S, Blum LK, Ju C-H, Lahey LJ, Lu DR, et al. Barcode-enabled sequencing of plasmablast antibody repertoires in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:2706–15.

Padyukov L, Silva C, Stolt P, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L. A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3085–92.

Ossipova E, Cerqueira CF, Reed E, Kharlamova N, Israelsson L, Holmdahl R, et al. Affinity purified anti-citrullinated protein/peptide antibodies target antigens expressed in the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R167.

Hansson M, Mathsson L, Schlederer T, Israelsson L, Matsson P, Nogueira L, et al. Validation of a multiplex chip-based assay for the detection of autoantibodies against citrullinated peptides. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R201.

Shi J, van Steenbergen HW, van Nies JAB, Levarht EWN, Huizinga TWJ, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, et al. The specificity of anti-carbamylated protein antibodies for rheumatoid arthritis in a setting of early arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:339.

Bergum B, Koro C, Delaleu N, Solheim M, Hellvard A, Binder V, Jonsson R, Valim V, Hammenfors DS, Jonsson MV, Mydel P. Antibodies against carbamylated proteins are present in primary Sjögren's syndrome and are associated with disease severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015.

Acknowledgements

We thank EIRA participants, research nurses and the EIRA study group, for their contributions; Professor Lars Klareskog, for establishing the EIRA study, and for support and scientific input; scientists previously involved in the generation of data for the EIRA database: Drs Leonid Padyukov, Patrick Stolt and Camilla Bengtsson; and Drs Per Matsson, Mats Nystrand and Thomas Schlederer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) for their scientific support concerning the ISAC platform. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Rheumatic Foundation and the EU-funded FP7 project TRIGGER (FP7-Health-2013-306029).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

Drs Hansson and Rönnelid are partners with Thermo Fisher Scientific within the Innovative Medicines Initiative, a public–private partnership between the EU and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries (see http://btcure.eu). Dr Mathsson-Alm works at Thermo Fisher Scientific on the Innovative Medicines Initiative project. Thermo Fisher Scientific contributes to this consortium with in-kind contributions for the development of the ISAC assay used in the current study. KL is co-inventor of patent US12/524,465, describing the diagnostic use of the CEP-1 epitope. No non-financial conflicts of interest exist.

Authors’ contributions

ER performed all ELISA and peptide absorption experiments, purified anti-CEP-1 and anti-CCP2 antibodies and together with KL wrote the manuscript and selected references. XJ performed statistical analysis of EIRA data and produced Tables 1 and 2. NK performed western blot experiments in Fig. 1. JY performed mass spectrophotometric analysis of modified proteins. AC was responsible for recruiting and obtaining serum samples from patients with RA for purification of ACPAs. LI developed the ELISA methods used. LM-A and MH performed and analyzed ISAC experiments. LA supervised the work of XJ and is responsible for administrating the EIRA study. JR provided scientific feedback, helped structure the study and performed some of the statistical analyses. All authors helped revise, read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Supplementary tables and methods. Table S1 α-enolase peptide sequences. Table S2 Association between PTPN22 polymorphism and RA in subgroups of patients, divided based on the presence/absence of anti-CEP-1 and anti-carb-CEP-1 IgG. (DOCX 22 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Reed, E., Jiang, X., Kharlamova, N. et al. Antibodies to carbamylated α-enolase epitopes in rheumatoid arthritis also bind citrullinated epitopes and are largely indistinct from anti-citrullinated protein antibodies. Arthritis Res Ther 18, 96 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1001-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1001-6