Abstract

Background

Systemic sclerosis (SSc)-related interstitial lung disease (ILD) has phenotypic similarities to lung involvement in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP). We aimed to assess whether genetic susceptibility loci recently identified in the large IIP genome-wide association studies (GWASs) were also risk loci for SSc overall or severity of ILD in SSc.

Methods

A total of 2571 SSc patients and 4500 healthy controls were investigated from the US discovery GWAS and additional US replication cohorts. Thirteen IIP-related selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped and analyzed for their association with SSc.

Results

We found an association of SSc with the SNP rs6793295 in the LRRC34 gene (OR = 1.14, CI 95 % 1.03 to 1.25, p value = 0.009) and rs11191865 in the OBFC1 gene (OR = 1.09, CI 95 % 1.00 to 1.19, p value = 0.043) in the discovery cohort. Additionally, rs7934606 in MUC2 (OR = 1.24, CI 95 % 1.01 to 1.52, p value = 0.037) was associated with SSc-ILD defined by imaging. However, these associations failed to replicate in the validation cohort. Furthermore, SNPs rs2076295 in DSP (β = -2.29, CI 95 % -3.85 to -0.74, p value = 0.004) rs17690703 in SPPL2C (β = 2.04, CI 95 % 0.21 to 3.88, p value = 0.029) and rs1981997 in MAPT (β = 2.26, CI 95 % 0.35 to 4.17, p value = 0.02) were associated with percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC%) even after adjusting for the anti-topoisomerase (ATA)-positive subset. However, these associations also did not replicate in the validation cohort.

Conclusions

Our results add new evidence that SSc and SSc-related ILD are genetically distinct from IIP, although they share phenotypic similarities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Systemic sclerosis or scleroderma (SSc) is a complex autoimmune disease characterized by vasculopathy, autoantibody production and fibrosis in the skin and internal organs. The etiology of SSc remains unknown; effective treatments that target the underlying pathophysiology of SSc are unavailable and the disease-related mortality remains high [1]. Specifically, pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) account for the majority of disease-related deaths in SSc [2]. SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) is usually characterized by a histologic pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) or, less frequently, usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). SSc-ILD has clinical and radiologic similarities to idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP). A polymorphism in the MUC5B promoter region was strongly associated with familial and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF; the most common IIP type) [3], but it has not been found to be a susceptibility locus for SSc or SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) [4–6].

Recently, large genome-wide association studies (GWASs) in fibrotic IIP (n = 1616 patients) and IPF (n = 542 patients and two validation cohorts n = 544 and n = 324) identified/confirmed susceptibility single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in TERT, AZGP1, MUC2, IVD, DSP, MAPT, DPP9, LRRC34, FAM13A, OBFC1, CSMD1, ATP11A [7] and TOLLIP, MDGA2, SPPL2C [8]. Given the clinical and radiologic similarities between SSc-ILD and IIP, we examined the association of the 13 SNPs among the listed genes, identified in the above IIP and IPF GWASs [7, 8] (TOLLIP and MDGA2 genes were excluded because the related SNPs were not present on the Illumina BeadChip utilized in SSc GWAS) with SSc as a single disease entity, with SSc-ILD by imaging, or SSc-ILD severity (as determined by percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC%)) in two large SSc patient samples.

Methods

Study population

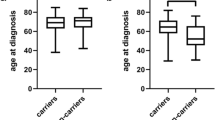

Two non-Hispanic white populations (discovery and replication cohorts) were investigated. For the discovery cohort, we utilized data from our previously published SSc GWAS study consisting of 1486 SSc cases (patients from the US) and 3477 unaffected race- and ethnicity-matched controls [9]. Selected polymorphisms were genotyped in an independent replication cohort consisting of 1085 additional SSc cases (patients from the US and Canada) and 1023 additional unaffected controls. Patients were recruited at the University of Texas – Houston and from the following sites: the participating Canadian Scleroderma Research Group (CSRG) sites, University of California Los Angeles, University of Michigan, Georgetown University, Boston University, Medical University of South Carolina, Johns Hopkins University, University of Utah, Northwestern University, University of Alabama at Birmingham and University of Minnesota. All patients were enrolled in the National Scleroderma Family Registry and DNA Repository. All patients with SSc fulfilled the 1980 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for SSc or had at least three of the five CREST (Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, Telangiectasias) features (Table 1).

The genotypes of unaffected controls for the discovery cohort were obtained from the Cancer Genetic Markers of Susceptibility (CGEMS; non-cancer healthy controls) studies and Illumina iControlDB database (www.illumina.com/iControlDB, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The unaffected controls for the replication cohort were recruited through a nationwide effort by the Scleroderma Family Registry and DNA Repository.

Collection of blood samples and clinical information from case and control subjects was undertaken with fully informed consent and relevant ethical review board approval from each contributing center in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

SNP selection and genotyping assay

In the discovery cohort, genotyping was performed using the Illumina Bead-Array GWAS platform. Specifically, patients were genotyped using Illumina Human 610-Quad BeadChip and controls were genotyped on Illumina Hap550K-BeadChip [9]. The 13 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified/confirmed to be associated with IIP [7], rs2736100 (TERT), rs2076295 (DSP), rs4727443 (AZGP1), rs7934606 (MUC2), rs2034650 (IVD), rs1981997 (MAPT), rs12610495 (DPP9), rs6793295 (LRRC34), rs2609255 (FAM13A), rs11191865 (OBFC1), rs1278769 (ATP11A), rs1379326 (CSMD1) and an additional SNP rs17690703 (SPPL2C) [8], were investigated in the discovery cohort. We also investigated association of 13 SNPs with anti-topoisomerase 1 antibody (ATA) and anti-centromere antibody (ACA) positive subgroup patients. The SNPs reaching a nominal level of significance (p < 0.05) in the discovery cohort (rs6793295 and rs11191865) were genotyped in the replication cohort using TaqMan allele discrimination assays in a 7900HT fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

SSc-ILD and severity of SSc-ILD

We also investigated the association of the above SNPs with SSc-ILD by imaging. We compared the frequency of the above SNPs in patients with SSc-ILD to unaffected controls. SSc-ILD was defined by chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT)/chest X-ray images. SSc patients (total = 498; n = 185 in the discovery cohort and n = 313 in the replication cohort) were considered to have interstitial lung disease (ILD) by imaging if they had: (1) ground glass opacity or increased interstitial markings on chest HRCT; or (2) increased basilar reticular marking on chest X-ray (in total, 498 patients, 185 in the discovery cohort and 313 in the replication cohort had ILD). The number of patients with imaging-proven ILD is low because HRCT imaging results were available only n = 212 in the discovery cohort and n = 347 in the replication cohort patients. The case-case comparison in regard to presence of ILD was compared by the low number of patients with available HRCT imaging in the discovery cohort.

Furthermore, an association with severity of ILD was investigated. Percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC%) (measured in a total of 1954 patients; n = 1072 in the discovery cohort and n = 882 in the replication cohort) as a continuous variable was used as a surrogate for severity of SSc-ILD as this has been demonstrated to be a validated outcome measure for severity of ILD in randomized controlled studies of patients with SSc [10]. SNPs reaching the nominal significance level (p < 0.05) in these two analyses were also genotyped in the replication cohort (rs7934606, rs2076295, rs17690703 and rs1981997).

Statistical analysis

We followed the same genetic inheritance modes for each specific SNP that was utilized in the IIP GWAS [7]. Specifically, all SNPs except for rs1379326 (CSMD1) were investigated in an additive model. Similar to the IIP GWAS [7], rs1379326 (CSMD1) was investigated in a recessive model. The additive model corresponds to the risk or protective effect conferred by the rarer (minor) allele (0, 1 or 2 copies) as a predictor of phenotypic status; and the recessive model corresponds to the effect conferred by only homozygous status for the rarer allele. Genotype data quality was verified for each SNP by testing for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed by an x 2 test or Fisher’s exact test. None of the included cohorts showed significant deviation from HWE for all the genotyped SNPs. Logistic regression that included both patients and controls was utilized to examine the association of the above SNPs with SSc overall and SSc-ILD. A linear regression model was used to investigate the association of these genetic variants with FVC% predicted (data was normally distributed) as a continuous variable, among patients only. FVC% predicted was investigated as a continuous rather than a dichotomous variable to increase our power to detect a difference in FVC levels conditional on the genotype. Anti-topoisomerase 1 antibody (ATA) status was included as a potential confounder in the multivariable regression model. The combined analysis of the discovery and the replication cohorts was performed via a random-effects meta-analysis model.

Results

Discovery cohort

We first investigated whether the 13 IIP-associated polymorphisms were associated with risk of SSc overall or with SSc-ILD. Several SNPs showed nominally significant associations with SSc in the discovery cohort (Table 2). Specifically, LRRC34 rs6793295 (OR = 1.14, CI 95 % 1.03 to 1.25, p value = 0.009) and OBFC1 rs11191865 (OR = 1.09, CI 95 % 1.00 to 1.19, p value = 0.043) were associated with SSc compared to controls (Table 2). There were no significant associations observed when the SNP frequencies in SSc antibody subgroups (ATA- or ACA-positive patients) were compared to controls (Table 3).

Next, we investigated the association in the discovery cohort between the above polymorphisms and SSc-ILD by imaging or FVC% predicted in order to investigate the relationship with SSc-ILD presence or severity. We also performed case-case comparison by presence of ILD with no ILD in SSc. Interestingly, rs7934606 in MUC2 (OR = 1.24, CI 95 % 1.01 to 1.52, p value = 0.037) was associated with SSc-ILD by imaging when compared to controls (Table 4). Furthermore, three polymorphisms DSP rs2076295 (β = -2.29, CI 95 % -3.85 to -0.74, p value = 0.004) SPPL2C rs17690703 (β = 2.04, CI 95 % 0.21 to 3.88, p value = 0.029) and MAPT rs1981997 (β = 2.26, CI 95 % 0.35 to 4.17, p value = 0.02) were associated with FVC% predicted (Table 5). Of note, the minor allele (A) of MAPT rs1981997 and (T) of SPPL2C rs17690703 were associated with higher FVC% predicted, which is consistent with the IIP GWAS results with the minor allele being protective in that study (OR < 1) [7]. Even after adjustment for ATA status, the above three polymorphisms showed nominally significant associations with ILD severity in SSc patients (Table 5). SPPL2C rs17690703 was associated ILD-SSc compared to SSc with no ILD as determined by imaging in the discovery cohort (Table S1 in Additional file 1).

Replication cohort and combined analysis

We genotyped the samples from the validation set for the above six SNPs, which either showed nominally significant associations (p < 0.05) with risk of SSc overall (LRRC34 rs6793295 and OBFC1 rs11191865) or with SSc-ILD (rs7934606 in MUC2) and FVC% predicted (DSP rs2076295, SPPL2C rs17690703 and MAPT rs1981997). However, these associations were not found in the replication cohort (Table 4 and upper part of Table 6). Contrary to the discovery cohort, MAPT rs1981997 (OR = 0.79; CI 95 % 0.68 to 0.91; p value = 0.002) and SPPL2C rs17690703 (OR = 0.64; CI 95 % 0.49 to 0.83; p value = 0.001) were associated with SSc susceptibility but not with ILD severity in the replication cohort (Table 6). Furthermore, SPPL2C rs17690703 was not associated with SSc-ILD when compared to SSc without ILD by imaging in the validation cohort (Table S1 in Additional file 1).

In the combined discovery and replication cohorts (lower part of Table 6), only the LRRC34 rs6793295 was associated with risk of SSc overall (OR = 1.11; CI 95 % 1.03 to 1.2; p value = 0.01). However, the observed significance level was not stronger in the combined cohort than in the discovery cohort and this association did not withstand correction for multiple comparisons. Specifically, the p value = 0.13 in the combined cohort after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, LRRC34 rs6793295 was not associated with FVC% predicted in the combined cohort. SPPL2C rs17690703 was associated with FVC% predicted in the combined cohort but not after ATA adjustment or with overall SSc risk (Table 6). The observed association of SPPL2C rs17690703 with FVC% did not withstand correction for multiple comparison (p corr = 0.078).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess genetic components of SSc and SSc-related ILD, specifically to determine if SSc-ILD and IIP share common genetic risk factors. We analyzed 13 SNPs which showed robust association with IIP in a previous GWAS report [7, 8]. However, we failed to replicate these associations with SSc or SSc-related ILD in a large North American cohort.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is the most common pulmonary manifestation in patients with SSc [11] and is the most frequent cause of SSc disease-related death [12]. ILD occurs with greater frequency and increased severity in patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc (dc-SSc) and in ATA-positive patients. In SSc-ILD, loss of lung function and extent of fibrosis are the most important prognostic factors. It is known that genetic factors contribute not only to SSc susceptibility, but also to predisposition to SSc clinical phenotypes including disease type (limited versus diffuse cutaneous disease) and autoantibody status [13]. Recently, several lines of evidence have suggested that, even though SSc-ILD has phenotypic similarities to IIP, the genetic risk factors for these two conditions are quite different. For example the MUC5B promoter region polymorphism (rs868903), which was strongly associated with familial and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [3, 7], was not identified as a susceptibility locus for SSc or SSc–associated interstitial lung disease [4–6]. In addition, the two large SSc GWAS reports (each with independent discovery and validation cohorts) identified the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II region as being the most strongly associated region with SSc [9, 14], whereas MHC loci were not found to be risk factors in the IIP GWAS [7].

The present study has some limitations. In our study, only a subgroup of SSc patients had undergone HRCT. We performed a case-case comparison in regard to presence of SSc-ILD versus no SSc-ILD in the low number of patients because HRCT results were not available in the remainder of patients. The genotype results for TOLLIP and MDGA2 genes were not available on our GWAS platform and could not be investigated. Furthermore, this is a cross-sectional study, thus, we cannot examine whether the investigated genetic loci have predictive significance for ILD progression. However, mean disease duration of this study was more than 10 years and most of the SSc-ILD cases had been already established. Therefore, we believe the cross-sectional FVC% is a reasonable surrogate for severity of ILD.

Conclusions

In this study, we confirm that genetic susceptibility loci for IIP are not risk loci for SSc or severity of SSc-ILD in two validation SSc cohorts of non-Hispanic white ethnic background. Our findings and those of previous genetic susceptibility studies in SSc [15] implicate pathways in innate and adaptive immunity, whereas susceptibility loci for IIP relate to epithelial cell injury/dysfunction and abnormal wound healing [16]. Future challenges will be to identify the functional relevance of these variants for the final common pathway that results in the phenotype of fibrotic lung disease. This study represents an important step forward toward a better understanding of the complex genetic association of SSc particularly with lung involvement. We add new evidence that SSc and SSc-ILD are genetically distinct from IIP.

Abbreviations

- ACA:

-

Anti-centromere antibody

- ATA:

-

Anti-topoisomerase 1 antibody

- CGEMS:

-

Cancer Genetic Markers of Susceptibility

- CREST:

-

Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, Telangiectasias

- dcSSc:

-

Diffuse cutaneous SSc

- FVC%:

-

Percent predicted forced vital capacity

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- HRCT:

-

High-resolution computed tomography

- HWE:

-

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- IIP:

-

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia

- ILD:

-

Interstitial lung disease

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- MHC:

-

Major histocompatibility complex

- NSIP:

-

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- PAH:

-

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- SSc:

-

Systemic sclerosis

- SSc-ILD:

-

SSc-associated interstitial lung disease

- UIP:

-

Usual interstitial pneumonia

References

Elhai M, Meune C, Avouac J, Kahan A, Allanore Y. Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:1017–26.

Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, Airo P, Cozzi F, Carreira PE, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1809–15.

Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, Loyd JE, et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1503–12.

Stock CJ, Sato H, Fonseca C, Banya WA, Molyneaux PL, Adamali H, et al. Mucin 5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with development of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis or sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2013;68:436–41.

Borie R, Crestani B, Dieude P, Nunes H, Allanore Y, Kannengiesser C, et al. The MUC5B variant is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease in the European Caucasian population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70621.

Peljto AL, Steele MP, Fingerlin TE, Hinchcliff ME, Murphy E, Podlusky S, et al. The pulmonary fibrosis-associated MUC5B promoter polymorphism does not influence the development of interstitial pneumonia in systemic sclerosis. Chest. 2012;142:1584–8.

Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, Peljto AL, Brown KK, Steele MP, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:613–20.

Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma SF, Flores C, Barber M, Huang Y, et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:309–17.

Radstake TR, Gorlova O, Rueda B, Martin JE, Alizadeh BZ, Palomino-Morales R, et al. Genome-wide association study of systemic sclerosis identifies CD247 as a new susceptibility locus. Nat Genet. 2010;42:426–9.

Furst D, Khanna D, Matucci-Cerinic M, Clements P, Steen V, Pope J, et al. Systemic sclerosis - continuing progress in developing clinical measures of response. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1194–200.

Ramirez A, Varga J. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Treat Respir Med. 2004;3:339–52.

Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:940–4.

Gorlova O, Martin JE, Rueda B, Koeleman BP, Ying J, Teruel M, et al. Identification of novel genetic markers associated with clinical phenotypes of systemic sclerosis through a genome-wide association strategy. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002178.

Allanore Y, Saad M, Dieude P, Avouac J, Distler JH, Amouyel P, et al. Genome-wide scan identifies TNIP1, PSORS1C1, and RHOB as novel risk loci for systemic sclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002091.

Wu M, Mayes MD. Insights into the genetic basis of systemic sclerosis: immunity in human disease and in mouse models. Adv Genomics Genet. 2014;4:143–51.

Spagnolo P, Grunewald J, du Bois RM. Genetic determinants of pulmonary fibrosis: evolving concepts. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:416–28.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marilyn Perry and Yuxiao Du for their work as Registry coordinators and we are grateful for the generous participation of our subjects. This work was supported by the Scleroderma Foundation New Investigator Award to Dr. Wu, and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) Centers of Research Translation (CORT) grant P50AR054144 to Dr. Mayes, NIH grant K23AR061436 to Dr. Assassi, NIH/NIAMS Scleroderma Family Registry and DNA Repository grant N01-AR02251 to Dr. Mayes, NIH/NIAMS grant AR055258 to Dr. Mayes, NIH National Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences grant 3UL1RR024148, Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program W81XWH-13-1-0452, Proposal number PR120687 to Dr. Mayes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MW, SA, JV, and MDM contributed to study conception and design, MW, SA, GAS, JC, MLT, KL, FMW, LKH, AAS, MH, DK, ES, KP, DEF, VS, MB, MH, XZ, JP, NJ, PD, NAK, DR, RWS, RMS, TMF, BJF, MJF, JAM, BMS, MM, JM, JV, and MDM contributed to acquisition of data. MW, SA, GAS, CP, OYG, WVC, JC, MLT, KL, FMW, LKH, AAS, MH, DK, ES, KP, DEF, VS, MB, MH, XZ, JP, NJ, PD, NAK, DR, RWS, RMS, TMF, BJF, MJF, JAM, BMS, MM, JM, JV, and MDM contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. MW had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Association between the investigated genotypes in SSc-ILD (by imaging) patients compared to SSc-no ILD (by imaging) in the discovery and replication cohort. (DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, M., Assassi, S., Salazar, G.A. et al. Genetic susceptibility loci of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia do not represent risk for systemic sclerosis: a case control study in Caucasian patients. Arthritis Res Ther 18, 20 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-0923-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-0923-3