Abstract

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a prevalent disorder. However, few studies have evaluated the effect of treatment interventions on biomarker expression. The aim of this review was to explore the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on inflammatory biomarker expression, specifically cytokines, neuropeptides and C-reactive protein (CRP), in FM patients.

Method

A literature search using PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO and the Cochrane library was performed from January 1990 to March 2015. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs published in English, French or Spanish were eligible.

Results

Twelve articles with a total of 536 participants were included. After exercise, multidisciplinary, or dietary interventions in FM patients, interleukin (IL) expression appeared reduced, specifically serum IL-8 and IL-6 (spontaneous, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced, or serum). Furthermore, the changes to insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels might indicate a beneficial role for fatigue in obese FM patients. In contrast, evidence of changes in neuropeptide and CRP levels seemed inconsistent.

Conclusion

Despite minimal evidence, our findings indicate that exercise interventions might act as an anti-inflammatory treatment in FM patients and ameliorate inflammatory status, especially for pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additional RCTs focused on the changes to inflammatory biomarker expression after non-pharmacological interventions in FM patients are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a prevalent disorder that affects to 2–8 % of the population [1–3], and it is characterized by widespread pain, fatigue, memory problems and sleep disturbances. Currently, it is one of the most common disorders seen by primary care physicians [4] and the second most common rheumatic disorder after osteoarthritis [5].

There are many possible treatments for FM that can be classified as pharmacological and non-pharmacological, and the latter can also be subclassified into psychological and non-psychological interventions [6–12]. The efficacy of these treatments is considered low to moderate, and there are no significant differences between them when administered in primary care or specialized settings [13].

The main criteria assessed in pharmacological and non-pharmacological trials are function, quality of life, pain, depression, anxiety and fatigue. All of these are subjective symptoms assessed by questionnaire and are rated by the patient or the clinician. However, few trials on FM include biological outcomes, in particular an assessment of inflammatory biomarkers, despite neurogenic neuroinflammation having been associated with the pathogenesis of FM [14]. As mentioned, non-pharmacological treatments are systematically recommended as an adjunctive treatment for FM [10]; therefore our aim was to determine the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on inflammatory biomarkers in FM patients, specifically cytokines, neuropeptides, and C-reactive protein (CRP).

Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA) [15].

Search strategy and data extraction

A comprehensive computerized literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO and the Cochrane library was performed from January 1990 to March 2015 by an expert in this field (MSV). The starting date was established because the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for the classification, with the definition of FM, were published in 1990 [16]. For example, the following search terms for the PubMed database were used: (“fibromyalgia” [MeSH Terms] OR “fibromyalgia” [All Fields] OR “Fatigue Syndrome, Chronic” [Mesh]) AND (“Cytokines” [Mesh] OR “Interleukins” [Mesh] OR “Biological Markers” [Mesh] OR “Neuropeptides” [Mesh] OR “C-Reactive Protein” [Mesh] OR biomarker* OR cytokine* OR interleukin* OR neuropeptide* OR “C-reactive protein” OR CRP).

The reference lists of the identified original articles and reviews were also searched manually for additional studies. The literature search was conducted independently by two authors (KS and MCPY). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus, and when in doubt, the final decision was made in consultation with a third author (JGC). The last search was conducted on 13 March 2015.

Eligibility criteria

The study eligibility criteria are shown in Table 1. We excluded studies from the following cases: the first trial was conducted in patients not only with FM but also with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (e.g., Light et al. [17]); the second excluded trial used biomarkers as predictors or related factors to symptom severity (e.g., Ross et al. [18]); the third assessed a mixed type treatment plan with pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention [19]; the fourth conducted exercise tests [20–22]; the fifth was written in German [23]; and the sixth was published as a letter [24].

Assessment of study quality

The risk-of-bias tool is generally fitted to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), but we can apply it to non-RCTs, and a specific tool for this use is under development [25]. In this systematic review, the risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [25].

Results

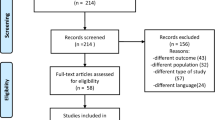

After the initial search of 535 records, 64 were found to be duplicates (Fig. 1). We screened the titles and abstracts, and 15 articles were assessed as full text. We finally included 12 articles with a total of 536 participants.

Algorithm for study selection (following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines, Shamseer et al., [15])

Characteristics of included studies

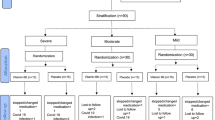

Of all of the included articles, two studies [26, 27] were conducted with almost the same population. With regard to interventions, three types were assessed: complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (e.g., balneotherapy, massage, mud bath, guided imagery, dance/movement therapy, and dietary therapy), exercise, and multidisciplinary therapy. All of the FM patients were diagnosed by the 1990 ACR criteria [16] (Ortega et al. [28] did not declare the year of the ACR criteria), and the mean age of the participants ranged from 43.4 to 57.0 years old (Ortega et al. [28, 29] did not declare age). With respect to study design, we included eight RCTs, and the remaining four articles included were non-RCTs. According to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [25], two studies [30, 31] were considered high quality, but the other trials were low quality with a high risk of bias (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, of our included trials, only four trials [26, 27, 32, 33] were performed under active control conditions, although two trials [26, 27] were almost the same population. None of these studies included evidence about how the participants rated both the primary and active control conditions as credible, and the likelihood of producing positive results due to baseline intervention expectations was not evaluated. Meanwhile, in relation to the baseline values of each biomarker, our findings revealed that the baseline levels of IL-8 and CRP in FM patients are significantly increased when compared to the healthy control group [28, 34].

Cytokines

We included nine articles with a total of 440 participants. The characteristics of each study are shown in Table 2. Of all of the studies, 10 of the biomarkers examined were classified as pro-inflammatory cytokines, 4 were classified as anti-inflammatory cytokines, 5 were classified as growth factors and 3 were classified as chemokines. Of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-8 were the most frequently measured in five studies each ([26, 28–31], [26, 28, 31, 34, 35], respectively), and IL-1β and TNF-α were second in three studies each [28, 29, 31]. Of the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10 was measured in three studies [28, 29, 31]. For growth factors, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP3), and nerve growth factor (NGF) were measured in two studies each [26, 27]. Of the chemokines, IL-8 was assessed in five studies [26, 28, 31, 34, 35].

In terms of pro-inflammatory cytokines, three trials [28, 34, 35] observed that the serum levels of IL-8 in FM patients decreased within group between pre-intervention and 4 months post pool-aquatic exercise (p <0.001) [28] and 6 months post multidisciplinary therapy (p <0.05) [34], and among groups 8 months post pool-aquatic exercise (p <0.05) [35]. For IL-6, one trial [29] showed that the spontaneous and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced production of IL-6 in FM patients decreased within group between pre-intervention and 8 months post pool-aquatic exercise (p <0.001), although IL-6 levels increased within group between pre-intervention and 4 months exercise (p <0.001). In addition, Senna et al. [30] reported that the levels of serum IL-6 in the dietary therapy group decreased within group between baseline and post 6 months of intervention.

With regard to anti-inflammatory cytokines, the findings were inconsistent. Ortega et al. [29] demonstrated that the spontaneous production of IL-10 in FM patients decreased within group between pre-intervention and 8 months post pool-aquatic exercise (p <0.001), whereas LPS induced IL-10 to increase (p <0.05) within group. With respect to growth factors, Bjersing et al. [27] showed that the levels of total serum IGF-1 in lean FM patients increased within group after 15 weeks of Nordic walking (p <0.05).

Neuropeptides

We included five articles with a total of 193 participants. Of these articles, two studies [26, 27] were also included in the group that utilized cytokines and were conducted with almost the same population. The characteristics of each study are shown in Table 3. Of all of the studies, nine of the biomarkers examined were neuropeptides. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) was measured in three studies [26, 27, 36], and the others were assessed in one study each.

For NPY, two trials [27, 36] demonstrated no consistent findings. Bjersing et al. [27] demonstrated that the levels of serum NPY in obese FM patients significantly increased within group after 30 weeks (including 15-week exercise and 15-week follow up) (p <0.05). By contrast, Bojner-Horwitz et al. [36] reported that the levels of serum NPY in both the dance/movement group and the control group increased compared to baseline and month 14 of the study within each group.

In terms of other neuropeptides, the concentrations of urinary corticotropin releasing factor-like immunoreactivity (CRF-L1) in the massage group decreased within group after 6 weeks of massage treatment (p = 0.01) and 1 month after completed treatments (p <0.5) [32]. For brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), Bazzichi et al. [33] noted that the concentrations of serum BDNF significantly decreased within each group in both the 2-week balneotherapy group and the 2-week mud bath therapy group after 12 weeks (p <0.05, p <0.01, respectively). Furthermore, for resistin, Bjersing et al. [27] demonstrated that the levels of serum resistin in the group as a whole increased within group after 30 weeks (including 15 weeks of exercise and 15 weeks of follow up) (p <0.05), which correlated with decreased fatigue.

CRP

We included five articles with a total of 223 participants. All of these articles [28–31, 37] were also included in the group that utilized cytokines. The characteristics of each study are shown in Table 4.

Of these studies, Ardiç et al. [37] did not observe changes in serum CRP levels between pre- and post-balneotherapy intervention. Three trials [28–30] observed that the levels of serum CRP in the intervention group decreased within group compared to the baseline level after 4 months or 8 months of pool-aquatic exercise (p <0.05, each) [28, 29] and 6 months of dietary therapy [30]. Contrary to these trials, the remaining trial [31] showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the guided imagery group and the group receiving typical care in the levels of plasma CRP at baseline, 6 weeks or 10 weeks. Comparing the levels of CRP at baseline, three trials [28, 29, 31] indicated that the levels of CRP in FM patients were higher than the reference value.

Discussion

We aimed to assess the effects of non-pharmacological interventions on biomarkers (specifically cytokines, neuropeptides, and CRP) in patients with FM. Despite the importance of non-pharmacological interventions in FM patients, few studies have focused on changes to biomarkers after non-pharmacological intervention. In fact, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on this subject. We found only 12 articles that fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Of these articles, only one trial examined psychological interventions [31].

Cytokines

Our findings indicated that the levels of serum IL-8 in FM patients decreased after exercise or multidisciplinary interventions and those of IL-6 (spontaneous, LPS-induced, or serum) in FM patients tended to decrease after exercise or dietary interventions. For IL-8, three trials revealed a reduction in serum IL-8 levels between pre- and post-intervention, including 3 weeks of multidisciplinary exercise or 4 or 8 months of pool-aquatic exercise [28, 34, 35]. IL-8 is both a pro-inflammatory cytokine that activates neutrophils and a chemokine that plays an important role in the infiltration of neutrophils at inflammation sites [22]. For IL-6, one trial demonstrated a reduction of the spontaneous and LPS-induced production of IL-6 between pre-intervention and 8 months post exercise within group [29]. Moreover, another trial showed that the levels of serum IL-6 in the dietary therapy group decreased between baseline and after 6 months of intervention within group [30]. Taking into consideration these findings, exercise, in particular, could act as an anti-inflammatory influence in FM patients, although it could act as a pro-inflammatory influence in healthy individuals [21]. In other words, exercise interventions could improve the inflammatory status in FM patients, reaching values close to the basal levels in the healthy population, by adjusting the inflammatory-stress feedback mechanism [21].

In terms of anti-inflammatory cytokines, however, our findings were inconsistent. Ortega et al. [29] reported that the spontaneous production of IL-10 in FM patients decreased between pre-intervention and 8 months post exercise within group, whereas LPS-induced IL-10 to increase within group. It remains unclear if this discrepancy is related to only the diverse functions of IL-10 and other factors, or the smaller sample size.

In addition, with regard to growth factors, Bjersing et al. [27] demonstrated that the levels of total serum IGF-1 in lean FM patients increased after 15 weeks of exercise within group, whereas these levels were unchanged in overweight or obese FM patients within each group. They also found evidence of a positive influence of IGF-1 on fatigue. Given that the fatigue response exercise is related to levels of body mass index (BMI), changes in IGF-1 might indicate a beneficial role for fatigue in obese FM patients.

Neuropeptides and CRP

We found no consistent changes in the levels of neuropeptides or CRP due to non-pharmacological interventions. One trial [27] reported that the levels of serum NPY in obese FM patients significantly increased after 30 weeks (including 15 weeks of exercise and a 15-week follow-up) (p <0.05) within group, whereas in the other trial [36] they increased both in the dance/movement group and the control group compared to baseline after 14 months treatment, within each group.

With respect to other neuropeptides, however, some notable results have been observed, although only one trial was conducted to study each neuropeptide. Bjersing et al. [27] also reported that the levels of serum resistin in all FM patients increased after 30 weeks (including 15 weeks of exercise and 15-week follow up) within group, which correlated with decreased fatigue. In view of the abovementioned results, they noted that IGF-1 and resistin were involved in the mechanism that reduced fatigue after moderate exercise in FM patients.

Of the other trials, Lund et al. [32] demonstrated that the concentrations of urinary CRF-LI in the massage group decreased after 6 weeks of massage treatment and 1 month after completion of the treatments, within group. Furthermore, Bazzichi et al. [33] reported that the concentrations of serum BDNF significantly decreased in both 2-week balneotherapy and 2-week mud bath therapy after 12 weeks, within each group. Although these two trials [32, 33] were not exercise intervention but manipulative and body-based non-pharmacological interventions, CRF-L1 and BDNF could be used as indicators of the effects of each intervention in FM patients.

In terms of CRP, as with the neuropeptides, our findings were inconsistent. In three trials [28–30] the levels of serum CRP in the intervention group decreased compared to the baseline level after 4 or 8 months of pool-aquatic exercise (p <0.05, each), within group [28, 29] or 6 months of dietary therapy within group [30]. In contrast, another trial [31] noted that there were no significant differences in the levels of plasma CRP between the guided imagery group and the group receiving usual care at baseline, 6 weeks or 10 weeks. Further research comparing each non-pharmacological intervention, specifically psychological and non-psychological intervention, is required to clarify the changes in CRP levels in FM patients.

Limitations

The results of this review have several limitations. The primary limitation is the paucity and low quality of the included studies. We only included 12 articles (two trials were conducted with almost the same population), and of these, there were only 8 RCTs. The quality of the included trials has been assessed with the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [25], which showed that only two studies [30, 31] were considered high quality, whereas the others were low quality with a high risk of bias. With regard to publication bias, we did not conduct the investigation using funnel plot analysis due to the high levels of heterogeneity among studies, and small sample sizes [38], and unfortunately we were unable to make any inference from this.

Another limitation is the high heterogeneity of non-pharmacological interventions. They consisted of three types: CAM, exercise, and multidisciplinary therapy. Of these types of treatment, CAM was also divided into the following categories: mind-body therapies (e.g., guided imagery, dance/movement therapy), manipulative and body-based therapy (e.g., balneotherapy, massage, mud-bath), and biological-based therapies (e.g., dietary therapy) [39]. Furthermore, the duration of each intervention and each study had various patterns. In particular paying attention to follow up, of our included trials, six [26, 27, 32–34, 36] were conducted with a follow-up period, although two [26, 27] were based on almost the same population. Of these six trials, only two [32, 34] demonstrated that the effect of each intervention in the levels of biomarkers continued over the follow-up period within the intervention group. Lund et al. [32] showed that the concentrations of urinary CRF-L1 decreased over the 10-week study duration within the intervention group, and Wang et al. [34] reported that the levels of serum IL-8 decreased over the 6-month study duration within the intervention group. On the other hand, although we only included the studies with non-pharmacological interventions, there are few studies on the effect of pharmacological treatments in inflammatory biomarkers in FM, whereas it appears that antidepressants can normalize levels of some biomarkers such as ACTH [19]. Our results for each intervention should be interpreted carefully.

An additional limitation is the high variability of materials. Biomarkers were investigated in diverse materials: serum, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), urine, and saliva. Thus, a direct comparison of the results is hardly possible even when the same biomarker was compared.

Moreover, it is unclear whether our findings are exclusive to FM patients [21]. Of all of our included studies, only FM patients or FM patients and healthy subjects were included. The non-pharmacological interventions that were conducted in our selected articles might affect other inflammatory diseases. Ploeger et al. [40] reported that the inflammatory response in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases compared to the healthy population generally increased after acute exercise. Further research is needed to elucidate whether non-pharmacological interventions are effective only for patients with FM.

In addition, there are not enough studies on the effect of non-pharmacological interventions on inflammatory biomarkers in healthy individuals, and we are unable to compare these effects and be certain that the effects reported here are related to FM. For instance, exercise could act as an anti-inflammatory influence in FM patients, whereas it could act as a pro-inflammatory influence in healthy individuals [21]. Further research is required to explore whether the effects of non-pharmacological interventions on inflammatory biomarkers are different in FM patients compared to the healthy population.

Future directions

Our findings, above all else, highlight the need to conduct further RCTs focused on biomarker changes after non-pharmacological interventions in FM patients. The following provisions would be helpful to improve future research in FM patients. First, non-pharmacological interventions should include not only exercise but also psychological treatment. Only one trial, guided imagery has been conducted as a psychological intervention [31]. Of note, no study has assessed the efficacy of mindfulness on biomarkers except for cortisol [41] in FM patients. We need to elucidate the relationships between psychological interventions and biomarkers in patients with FM.

Second, biomarkers should be measured under the same conditions (e.g., controlling for menstrual phase and medications) to obtain homogeneous patient samples. As recommended in RCTs, control groups should be randomized and active, using standardized low-intensity non-pharmacological interventions (and not waiting list or non-active interventions). Follow up is mandatory and standardized periods should be accepted by researchers (for instance: post-treatment, 3-month and 12-month follow up). In addition, more neuropeptides should be included as biomarkers. Finally, the relationship between these biomarkers and pain-related measures deserves to be studied. Third, participants should be homogeneous, specifically for disease duration and age. Given that many of FM patients are female, more attention should be paid to the effects of menstruation. Moreover, participants who do not regularly take some kinds of medications (e.g., analgesic or psychotropic drugs) would be desirable. Future trials should be conducted with the aim of reducing the influence of these medications. On the other hand, participants would include not only patients with FM but also patients with other inflammatory diseases. Few studies have focused on comparing the effects of non-pharmacological interventions between FM and other inflammatory diseases.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that the levels of serum IL-8 in the patients with FM decreased after exercise or multidisciplinary interventions, and IL-6 levels (spontaneous, LPS-induced, or serum) in FM patients tended to decrease after exercise or dietary interventions. Exercise intervention, in particular, could act as an anti-inflammatory influence in FM patients, although it might act as a pro-inflammatory influence in a healthy population. To summarize, exercise interventions could ameliorate the inflammatory status of FM patients, generating values closer to the baseline levels of healthy individuals by regulating the inflammatory-stress feedback mechanism. However, our findings revealed discrepancies in the anti-inflammatory cytokines, but the changes in IGF-1 might indicate a beneficial role for fatigue in obese FM patients.

The results for neuropeptides and CRP seem to be inconsistent. Although only one trial was conducted on resistin, there was an increase in the levels of serum resistin in FM patients after an exercise period, which correlated with decreased fatigue. IGF-1 and resistin might be involved in the effects that reduce fatigue in FM patients. Furthermore, CRF-L1 and BDNF could be used as indicators of efficacy related to non-pharmacological interventions in FM patients.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- BDNF:

-

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CAM:

-

complementary and alternative medicine

- CFS:

-

chronic fatigue syndrome

- CRF-L1:

-

corticotropin releasing factor-like immunoreactivity

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CSF:

-

cerebrospinal fluid

- FM:

-

fibromyalgia

- IGF-1:

-

insulin-like growth factor 1

- IGFBP3:

-

IGF binding protein-3

- IL:

-

interleukin

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

- NGF:

-

nerve growth factor

- NPY:

-

neuropeptide Y

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trials

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

References

Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:19–28.

McBeth J, Jones K. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:403–25.

Vincent A, Lahr BD, Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Whipple MO, Oh TH, et al. Prevalence of Fibromyalgia: A Population-Based Study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, Utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:786–92.

Hawkins RA. Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Update. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2013;113:680–9.

Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Review. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:1547–55.

Choy E, Marshall D, Gabriel ZL, Mitchell SA, Gylee E, Dakin HA. A Systematic Review and Mixed Treatment Comparison of the Efficacy of Pharmacological Treatments for Fibromyalgia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:335–45.

Köllner V, Häuser W, Klimczyk K, Kühn-Becker H, Settan M, Weigl M, et al. Psychotherapy for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline. Schmerz. 2012;26:291–6. German.

Langhorst J, Häuser W, Bernardy K, Lucius H, Settan M, Winkelmann A, et al. Complementary and alternative therapies for fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline. Schmerz. 2012;26:311–7. German.

Sommer C, Häuser W, Alten R, Petzke F, Späth M, Tölle T, et al. Drug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline. Schmerz. 2012;26:297–310. German.

Ablin J, Fitzcharles MA, Buskila D, Shir Y, Sommer C, Häuser W. Treatment of Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Recommendations of Recent Evidence-Based Interdisciplinary Guidelines with Special Emphasis on Complementary and Alternative Therapies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:485272. doi:10.1155/2013/485272.

Fitzcharles MA, Ste-Marie PA, Goldenberg DL, Pereira JX, Abbey S, Choinière M, et al. 2012 Canadian Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia syndrome: Executive summary. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:119–26.

Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ, Bernardy K, Häuser W. Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:193–207.

Garcia-Campayo J, Magdalena J, Magallón R, Fernández-García E, Salas M, Andrés E. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of fibromyalgia treatment according to level of care. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R81.

Littlejohn G. Neurogenic neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia and complex regional pain syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2015.100.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647.

Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–72.

Light AR, Bateman L, Jo D, Hughen RW, Vanhaitsma TA, White AT, et al. Gene expression alterations at baseline and following moderate exercise in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Fibromyalgia Syndrome. J Intern Med. 2012;271:64–81.

Ross RL, Jones KD, Bennett RM, Ward RL, Druker BJ, Wood LJ. Preliminary evidence of increased pain and elevated cytokines in fibromyalgia patients with defective growth hormone response to exercise. Open Immunol J. 2010;3:9–18.

Bellometti S, Galzigna L. Function of the hypothalamic adrenal axis in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome undergoing mud-pack treatment. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1999;19:27–33.

Gürsel Y, Ergin S, Ulus Y, Erdoğan MF, Yalçin P, Evcik D. Hormonal Responses to Exercise Stress Test in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:401–5.

Bote ME, Garcia JJ, Hinchado MD, Ortega E. Fibromyalgia: Anti-Inflammatory and Stress Responses after Acute Moderate Exercise. PLoS One. 2013;8, e74524.

Torgrimson-Ojerio B, Ross RL, Dieckmann NF, Avery S, Bennett RM, Jones KD, et al. Preliminary evidence of a blunted anti-inflammatory response to exhaustive exercise in fibromyalgia. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;277:160–7.

Walz J, Hinzmann J, Haase I, Witte T. Whole body hyperthermia in pain therapy. A controlled trial on patients with fibromyalgia. Schmerz. 2013;27:38–45. German.

Sprott H, Franke S, Kluge H, Hein G. Pain treatment of fibromyalgia by acupuncture. Rheumatol Int. 1998;18:35–6.

Sterne JAC, Higgins JPT, Reeves BC, on behalf of the development group for ACROBAT-NRSI. A Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool: for Non- Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI). Version 1.0.0, 24 September 2014.

Bjersing JL, Dehlin M, Erlandsson M, Bokarewa MI, Mannerkorpi K. Changes in pain and insulin-like growth factor 1 in fibromyalgia during exercise: the involvement of cerebrospinal inflammatory factors and neuropeptides. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R162.

Bjersing JL, Erlandsson M, Bokarewa MI, Mannerkorpi K. Exercise and obesity in fibromyalgia: beneficial roles of IGF-1 and resistin? Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:34.

Ortega E, García JJ, Bote ME, Martín-Cordero L, Escalante Y, Saavedra JM, et al. Exercise in fibromyalgia and related inflammatory disorders: Known effects and unknown chances. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2009;15:42–65.

Ortega E, Bote ME, Giraldo E, García JJ. Aquatic exercise improves the monocyte pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production balance in fibromyalgia patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22:104–12.

Senna MK, Sallam RA, Ashour HS, Elarman M. Effect of weight reduction on the quality of life in obese patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:1591–7.

Menzies V, Lyon DE, Elswick Jr RK, McCain NL, Gray DP. Effects of guided imagery on biobehavioral factors in women with fibromyalgia. J Behav Med. 2014;37:70–80.

Lund I, Lundeberg T, Carleson J, Sönnerfors H, Uhrlin B, Svensson E. Corticotropin releasing factor in urine—A possible biochemical marker of fibromyalgia. Responses to massage and guided relaxation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;403:166–71.

Bazzichi L, Da Valle Y, Rossi A, Giacomelli C, Sernissi F, Giannaccini G, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to study the effects of balneotherapy and mud-bath therapy treatments on fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:111–20.

Wang H, Buchner M, Moser MT, Daniel V, Schiltenwolf M. The role of IL-8 in patients with fibromyalgia: a prospective longitudinal study of 6 months. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:1–4.

Bote ME, Garcia JJ, Hinchado MD, Ortega E. An exploratory study of the effect of regular aquatic exercise on the function of neutrophils from women with fibromyalgia: Role of IL-8 and noradrenaline. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;39:107–12.

Bojner-Horwitz E, Theorell T, Anderberg UM. Dance/movement therapy and changes in stress-related hormones: a study of fibromyalgia patients with video-interpretation. Arts Psychotherapy. 2003;30:255–64.

Ardiç F, Ozgen M, Aybek H, Rota S, Cubukçu D, Gökgöz A. Effects of balneotherapy on serum IL-1, PGE2 and LTB4 levels in fibromyalgia patients. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27:441–6.

Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;342:d4002.

Koithan M. Introducing Complementary and Alternative Therapies. J Nurse Pract. 2009;5:18–20.

Ploeger HE, Takken T, de Greef MHG, Timmons BW. The effects of acute and chronic exercise on inflammatory markers in children and adults with a chronic inflammatory disease: a systematic review. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2009;15:6–41.

Cash E, Salmon P, Weissbecker I, Rebholz WN, Bayley-Veloso R, Zimmaro LA, et al. Mindfulness Meditation Alleviates Fibromyalgia Symptoms in Women: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49:319–30.

Acknowledgements

We thank Red de Investigación en Actividades de Prevención y Promoción de la Salud (Research Network on Preventative Activities and Health Promotion) (REDIAPP-G06-170 and RD06/0018/0017) and Red de Excelencia PROMOSAM (PSI2014-56303-REDT), for its support in the development of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Within the past three years, Dr. Sanada has received consultant fees from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, and speaker’s fees from Eli Lilly, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Shionogi Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Astellas Pharma. The authors declare that they have neither financial nor non-financial competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KS, MGT, MMPD, MAD and JGC designed the research protocol and selection criteria. MSV performed the search strategy. KS, MAD and MCPY selected studies to be included. JGC, MSV and MGT contributed to organizing the data. MMPD performed an assessment of the risk of bias of the included articles. All of the authors interpreted the results, and all of them helped to draft and critically read the manuscript, and gave the final approval of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanada, K., Díez, M.A., Valero, M.S. et al. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on inflammatory biomarker expression in patients with fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Arthritis Res Ther 17, 272 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0789-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0789-9