Abstract

Background

Triatoma sordida is one of the main Chagas disease vectors in Brazil. In addition to Brazil, this species has already been reported in Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. It is hypothesized that the insects currently identified as T. sordida are a species subcomplex formed by three cytotypes (T. sordida sensu stricto [s.s.], T. sordida La Paz, and T. sordida Argentina). With the recent description of T. rosai from the Argentinean specimens, it became necessary to assess the taxonomic status of T. sordida from La Paz, Bolivia, since it was suggested that it may represent a new species, which has taxonomic, evolutionary, and epidemiological implications. Based on the above, we carried out molecular and experimental crossover studies to assess the specific status of T. sordida La Paz.

Methods

To evaluate the pre- and postzygotic barriers between T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s., experimental crosses and intercrosses between F1 hybrids and between F2 hybrids were conducted. In addition, cytogenetic analyses of the F1 and F2 hybrids were applied with an emphasis on the degree of pairing between the homeologous chromosomes, and morphological analyses of the male gonads were performed to evaluate the presence of gonadal dysgenesis. Lastly, the genetic distance between T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s. was calculated for the CYTB, ND1, and ITS1 genes.

Results

Regardless of the gene used, T. sordida La Paz showed low genetic distance compared to T. sordida s.s. (below 2%). Experimental crosses resulted in offspring for both directions, demonstrating that there are no prezygotic barriers installed between these allopatric populations. Furthermore, postzygotic barriers were not observed either (since the F1 × F1 and F2 × F2 intercrosses resulted in viable offspring). Morphological and cytogenetic analyses of the male gonads of the F1 and F2 offspring demonstrated that the testes were not atrophied and did not show chromosome pairing errors.

Conclusion

Based on the low genetic distance (which configures intraspecific variation), associated with the absence of prezygotic and postzygotic reproductive barriers, we confirm that T. sordida La Paz represents only a chromosomal polymorphism of T. sordida s.s.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Triatomines are hematophagous insects of great importance to public health, since they are considered the main form of transmission of the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas, 1909) (Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae), the etiological agent of Chagas disease [1]. This disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis) is a neglected disease that affects about eight million people worldwide and results in 10,000 deaths per year [1]. These insects defecate or urinate during or after hematophagy and, once infected by T. cruzi, release the infective form of the parasite in feces/urine [1], which may lead to contamination of the host.

The subfamily Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) is composed of 156 species, grouped into 18 genera and five tribes [2,3,4]. All species are considered potential vectors of Chagas disease, although the genera Triatoma Laporte, 1832, Rhodnius Stål, 1859, and Panstrongylus Berg, 1879, are considered the most important from an epidemiological point of view [5, 6].

Triatoma sordida (Stål, 1859) is one of the main Chagas disease vectors in Brazil, being the most commonly captured species in peridomestic Brazilian environments [5, 7], where it has already been reported to be naturally infected by T. cruzi [8]. In addition to Brazil, this species has been reported in Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, in the Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Cerrado, Chaco, and Pantanal biomes [3, 5, 9]. It is hypothesized that the insects currently identified as T. sordida could actually be a species subcomplex formed by three cytotypes (cytotype 1 determined as T. sordida sensu stricto [s.s.], cytotype 2 determined as T. sordida La Paz, and cytotype 3 determined as T. sordida Argentina) [9], which resulted in the recent description of T. rosai Alevi et al., 2020, from the Argentinean specimens (excluding Argentina in the geographic distribution of T. sordida) [3].

It was long believed that the diversification events of the different T. sordida cytotypes were based on cryptic speciation [9]. However, comparative morphological and morphometric studies between T. rosai and T. sordida (Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay), as well as between T. sordida from different countries, found phenotypic differences, demonstrating that it is not cryptic speciation [10]. With the recent description of T. rosai (from T. sordida cytotypes from Argentina), it became necessary to assess the taxonomic status of T. sordida from La Paz, Bolivia (referred to as T. sordida La Paz), since Panzera et al. [9] suggested that this cytotype composed of domestic populations from La Paz, Bolivia, may represent a new species, which has taxonomic, evolutionary and, above all, epidemiological implications.

According to Panzera et al. [9], T. sordida La Paz represents a “chromosomal taxon,” but these authors do not rule out the possibility that T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s. may be conspecific populations with different ribosomal gene locations. Morphological, morphometric [11], and phylogenetic [12] studies have pointed to this hypothesis as the most viable. Assessing the specific status of T. sordida La Paz also has epidemiological implications, since different species may have different vectorial capacity and vector competence, such as T. sordida s.s. and T. rosai, which have different infection rates [3, 13,14,15,16,17]. Entomo-epidemiological studies indicate different infection rates between T. sordida from Brazil (0.5–41.9%) and Bolivia (16.2%) [14,15,16,17,18]. Thus, based on the above, we carried out molecular and experimental crossover studies to assess the specific status of T. sordida La Paz.

Methods

Experimental crosses

Experimental reciprocal crosses were conducted between T. sordida La Paz (Apolo, La Paz, Bolivia, collected in peridomiciliary ecotopes) and T. sordida s.s. (Corumbá, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, collected in peridomiciliary ecotopes). The insects used in the experiments came from colonies kept in the Triatominae insectary of the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, São Paulo State University (UNESP), Araraquara, São Paulo, Brazil. The experimental crosses were conducted in the Triatominae insectary, according to the experiments of Correia et al. [19] and Mendonça et al. [20]: the insects were sexed as fifth-instar nymphs [21], and males and females were kept separate until they reached the adult stage to guarantee the virginity of the insects used in the crosses. For the experimental crosses, three couples from each set were placed in plastic jars (diameter 5 cm × height 10 cm) and kept at room temperature (average of 24 °C [22]) and 63% average relative humidity [22]. Weekly, the eggs were collected, counted, and separated in new jars to assess the hatch rate. Upon reaching the fifth instar (N5), again three pairs of first-generation nymphs (F1) resulting from each interspecific cross were separated to perform intercrosses (F1 × F1) (Table 1), using the same parameters described above and again reviewed. Finally, the eggs of these crosses were counted and separated, and from the second-generation nymphs (F2), new backcrosses (F2 × F2) (Table 1) were performed to assess the hatching rate of the third generation (F3).

Molecular analysis

For molecular analysis, the genomic DNA of five parental insects used in crosses (T. sordida Apolo, La Paz, Bolivia, and T. sordida Corumbá, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, both collected in peridomiciliary ecotopes) was extracted from gonads using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Amplification of the fragments was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using primers targeting the CYTB [23], ND1 [24], and ITS1 genes [25] described in the literature. The amplified PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel and later purified using the GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, this material was submitted for direct sequencing using an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) sequencer, from the Human Genome and Stem Cell Research Center, University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil. The obtained sequences were manually edited using the BioEdit alignment editor v.7.0.5.3 and aligned using the ClustalW multiple sequence alignment tool. The genetic sequences are available on GenBank [access data: T. sordida s.s. CYTB (MZ700100), ND1 (MZ700102), and ITS1 genes (MZ648337); T. sordida La Paz CYTB (MZ700101), ND1 (MZ700103), and ITS1 genes (MZ648333)]. The genetic distance matrices between T. sordida s.s. and T. sordida La Paz for all genes were obtained with MEGA 7.0 software, using the Kimura-2-parameter distance model (K2P). Sequences available from GenBank of T. brasiliensis Neiva, 1911, for the CYTB (KC249239), ND1 (AM980619), and ITS1 genes (KJ125138) were used as outgroups.

Morphology of the gonads and cytogenetic analysis

After the experimental crosses (F1 × F1 and F2 × F2) (Table 1), the F1 and F2 males were dissected (n = 5), the testes were removed and stored in methanol/acetic acid solution (3:1). Before cytogenetic analysis, the morphology of the male gonads from the F1 and F2 hybrid specimens (n = 5) was analyzed under a Leica MZ APO stereoscopic microscope and analyzed through the Motic Images Advanced 3.2 image analysis system to evaluate the presence of gonadal dysgenesis (which may be unilateral or bilateral) [26]. Posteriorly, slides were prepared by the cell crushing technique as described by Alevi et al. [27]), and cytogenetic analysis was applied to characterize the spermatogenesis, with emphasis on the degree of pairing between the homeologous chromosomes [20], using the lacto-acetic orcein technique [27, 28]. The slides were examined using a Jenaval light microscope (Zeiss), coupled to a digital camera and AxioVision LE 4.8 image analysis software. The images obtained were magnified by a factor of ×1000.

Results and discussion

Extremely low genetic distance values were found between T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s. (Table 2). These results could be associated with the absence of prezygotic [represented by the hatching of F1 hybrids (Table 1)] and postzygotic barriers [represented by the absence of mortality among F1 hybrids that showed normal development and reached adulthood (absence of hybrid inviability) (Table 1), by obtaining F2 hybrids, demonstrating that the F1 hybrids were fertile (Table 1) and that they did not present atrophied gonads (Fig. 2) and produced viable gametes (Fig. 3) (absence of hybrid sterility) and by high F3 hatching rate (Table 1) associated with 100% pairing (Fig. 3) (absence of hybrid collapse)] installed between these allopatric populations (Table 1). These data indicate that T. sordida La Paz represents only a chromosomal polymorphism of T. sordida s.s.

Alevi et al. [3] and Belintani et al. [12] presented robust phylogenetic analyses using T. sordida s.s., T. sordida La Paz, and T. rosai. In both, T. sordida La Paz was recovered along with T. sordida s.s., and T. rosai was recovered as an independent strain. Morphological and morphometric analyses resulted in similar clusters as those above, since T. sordida s.s. and T. sordida La Paz showed characteristics similar to each other (that grouped them) and divergent from T. rosai [11].

Regardless of the gene used, T. sordida La Paz showed extremely low genetic distance compared to T. sordida s.s. (Table 2). Monteiro et al. [29] suggest that minimum interspecific distance in Triatominae should be greater than 2%. Triatoma rosai and T. sordida s.s., for example, have a distance greater than 8% (which confirmed the specific status of T. rosai) [3]. On the other hand, our results demonstrated that the greatest distance observed between T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s. was 1.9% (Table 2), which suggests that these cytotypes represent only intraspecific chromosomal variation.

Experimental crosses (Fig. 1) resulted in offspring for both directions (Table 1), demonstrating that there are no prezygotic barriers installed between these allopatric populations. These results demonstrate that beyond the physical barriers that may make it impossible to find these insects together in nature (because they inhabit different countries in South America [9]), there are no prezygotic barriers installed between T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s. Therefore, under laboratory conditions, these insects recognize each other (absence of ethological isolation) and copulate (absence of mechanical isolation), in addition to demonstrating gametic, genomic and, above all, zygotic (absence of gametic isolation) compatibility.

In triatomines, the detection of pre- and/or postzygotic barriers has helped in taxonomy and systematics, since evolutionarily more distant species have prezygotic barriers that prevent the formation of hybrids, while evolutionarily closely related species can produce hybrids that will decline (hybrid breakdown) by postzygotic barriers such as hybrid inviability, hybrid sterility, or hybrid collapse [30].

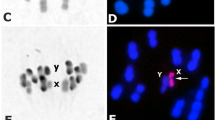

From F1 hybrids that reached adulthood, confirming the absence of postzygotic barrier of hybrid inviability, intercrosses were performed (Table 1) and F2 hybrids were obtained for all combinations (Table 1), also demonstrating the absence of the postzygotic barrier of hybrid sterility. The unfeasibility of the hybrids is represented by the high mortality rate, associated with their low adaptive value, during the nymphal stages [3]. This postzygotic barrier was extremely important in confirming the specific status of T. rosai [3]. On the other hand, hybrid sterility, which can be represented by atrophy of the gonads (gonadal dysgenesis) [26] or by chromosomal pairing errors which lead to the formation of unviable gametes [31], was also not observed, since F2 hybrids hatched (Table 1), and morphological analyses of the male gonads of the F1 and F2 offspring demonstrated that the testes were not atrophied compared to the control group—absence of gonadal dysgenesis (Fig. 2). Furthermore, cytogenetic analyses of the degree of pairing between the homeologous chromosomes of the F1 and F2 hybrids demonstrated genomic compatibility between the two cytotypes, as all chromosomes were paired during metaphases (Fig. 3), resulting in the formation of viable gametes.

Non-atrophied testicle of hybrid of T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s., demonstrating the absence of gonadal dysgenesis. a Testicle of T. sordida La Paz; b testicle of hybrid F1 of the crosses between T. sordida La Paz female × T. sordida s.s. male; c testicle of hybrid F2 of the crosses between T. sordida La Paz male × T. sordida s.s. female. Bar: 10 mm

Meiotic metaphases of hybrids F1 resulting from the experimental crosses between T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s. a, b Metaphases with correct pairing of the homeologous chromosomes. a Hybrid F1 of the crosses between T. sordida La Paz female × T. sordida s.s. male; b hybrid F1 of the crosses between T. sordida La Paz male × T. sordida s.s. female; X: sex chromosomes X, Y: sex chromosomes Y. Bar: 10 μm

For triatomines, all cases of hybrid sterility were associated only with errors during meiosis [31, 32]. The degree of pairing between the homeologous chromosomes of F1 hybrids allows us to evaluate the evolutionary relationship between the species [33]: in general, species that are phylogenetically closer range from about 90 to 100% chromosomal pairing (as observed among species of the T. brasiliensis complex [20, 34] and T. infestans subcomplex [23]), while more distantly related species show several pairing errors (40% or more), as observed between T. infestans and T. rubrovaria (Blanchard, 1843) [31]. Panzera et al. [9] presented cytogenetic analyses of four possible hybrids of T. sordida from Bolivia (two from Apolo, La Paz, and two from Izozog, Santa Cruz) and observed 100% chromosomal pairing and variations in 45S rDNA probe markings (which led the authors to consider these specimens hybrids). Our results indicate that the insects analyzed were only chromosomal variants of T. sordida s.s.

Nascimento et al. [35] combined molecular data and experimental crosses to synonymize R. taquarussuensis da Rosa et al., 2017, with R. neglectus Lent, 1954. The authors noted that the hatch rates of F1 offspring were the same as for parental crosses (greater than 78%). Our results demonstrate that the hatching rate of the F1 and F2 offspring was greater than 80%, and that of the F3 offspring was greater than 60% (Table 1), both of which were higher than the hatching rate observed to control crosses between T. sordida La Paz (Table 1). These results, combined with the low genetic distance data, also indicate that T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s. are the same species.

The hatching of viable hybrids up to F3 demonstrates the absence of a postzygotic barrier by hybrid collapse. Mendonça et al. [20] characterized this event for hybrids resulting from the crosses between T. lenti Sherlock & Serafim, 1967, and T. sherlocki Papa et al., 2002. The authors observed the absence of F3 for the cross between T. lenti female and T. sherlocki male and the presence of only two F3 nymphs for the cross between T. lenti male and T. sherlocki female, which died soon after hatching [20]. Furthermore, Mendonça et al. [20] analyzed the metaphases of F2 hybrids that were intercrossed and observed several chromosomal pairing errors (which resulted in the formation of nonviable gametes). The high F3 hatching rate associated with 100% pairing between the F2 hybrid chromosomes demonstrates that this evolutionary phenomenon is not occurring in hybrids of T. sordida La Paz and T. sordida s.s.

Conclusion

Based on the low genetic distance (which configures intraspecific variation) associated with the absence of prezygotic and postzygotic reproductive barriers, we confirm that T. sordida La Paz represents only a chromosomal polymorphism of T. sordida s.s.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

References

World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis). Accessed 12 May 2021.

Galvão C. Taxonomia dos Vetores da Doença de Chagas da Forma à Molécula, quase três séculos de história. In: Oliveira J, Alevi KCC, Camargo LMA, Meneguetti DUO, editors. Atualidades em Medicina Tropical no Brasil: Vetores. São Paulo: Strictu Sensu Editora; 2020. p. 9–37.

Alevi KCC, Oliveira J, Garcia ACC, Cristal DC, Delgado LMG, Bittinelli IF, et al. Triatoma rosai sp. Nov. (Hemiptera, Triatominae): a new species of Argentinian chagas disease vector described based on integrative taxonomy. Insects. 2020;11:830.

Zhao Y, Galvão C, Cai W. Rhodnius micki, a new species of Triatominae (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) from Bolivia. ZooKeys. 2021;012:71–93.

Galvão C. Vetores da doença de Chagas no Brasil. 1st ed. Curitiba: Sociedade Brasileira de Zoologia; 2014. p. 289.

Justi SA, Russo CAM, dos Mallet JRS, Obara MT, Galvão C. Molecular phylogeny of Triatomini (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). Parasite Vector. 2014;7:149.

Diotaiuti L, Pereira AS, Loiola CF, Fernandes AJ, Schofield JC, Dujardin JP, et al. Inter-relation of sylvatic and domestic transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi in areas with and without domestic vectorial transmission in Minas Gerais. Brazil Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1995;90:443–8.

Lent H, Wygodzinsky P. Revision of the Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) and their significance as vector of Chagas’s disease. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 1979;163:123–520.

Panzera F, Pita S, Nattero J, Panzera Y, Galvao C, Chavez T, et al. Cryptic speciation in the Triatoma sordida subcomplex (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) revealed by chromosomal markers. Parasit Vect. 2015;8:495.

Garcia ACC, Oliveira J, Cristal DC, Delgado LMG, Bittinelli IF, Galvão C, et al. Intraspecific and interspecific phenotypic differences confirm the absence of cryptic speciation in Triatoma sordida (Hemiptera, Triatominae). Am J Trop Med Hyg; 2021. in press.

Nattero J, Piccinali RM, Lopes CM, Hernandez ML, Abrahan L, Lobbia PA, et al. Morphometric variability among the species of the Sordida subcomplex (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae): evidence for differentiation across the distribution range of Triatoma sordida. Parasit Vect. 2017;10:412.

Belintani T, Oliveira J, Pinotti H, Silva LA, Alevi KCC, Galvão C, et al. Phylogenetic and phenotypic relationships of the Triatoma sordida subcomplex (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae). Acta Trop. 2020;212:105679.

Bar ME, Wisnievsky-Colli C. Triatoma sordida Stål 1859 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae: Triatominae) in palms of northeastern Argentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:895–9.

Castro GB, Machado EMM, Borges EC, Lorosa ES, Andrade RE, Diotaiuti L, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi Peridomiciliar transmission by Triatoma sordida in the municipality of Patis, Gerais State, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:434.

Lorosa ES, Andrade RE, Santos SM, Pereira CA. Estudo da infecção natural e da fonte alimentar do Triatoma sordida (Stal, 1859), (Hemiptera -Reduviidae) na região norte de Minas Gerais, Brazil, através da reação de precipitina. Entomol Vectores. 1998;5:13–22.

Brenière SF, Aliaga C, Waleckx E, Buitrago R, Salas R, Barnabé C, et al. Genetic characterization of DTUs in wild Triatoma infestans from Bolivia: predominance of TcI. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1650.

Rossi JCN, Duarte EC, Gurgel-Gonçalves R. Factors associated with the occurrence of Triatoma sordida (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in rural localities of Central-West Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110:192–200.

Lorosa ES, Cahet DMB, Andrade RE, Figueiredo JF, Jurberg J. O uso da técnica de precipitação no estudo do comportamento alimentar e grau de infectividade em Triatoma sordida (Stal 1859) (Hemiptera – Reduviidae), coletados no estado de Mato Grosso, Brasil. Entomol Vect. 2000;7:227–37.

Correia N, Almeida CE, Lima-Neiva V, Gumiel M, Lima MM, Medeiros LMO, et al. Crossing experiments confirm Triatoma sherlocki as a member of the Triatoma brasiliensis species complex. Acta Trop. 2013;128:162–7.

Mendonça VJ, Alevi KCC, Medeiros LM, Nascimento JD, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV, Rosa JA. Cytogenetic and morphologic approaches of hybrids from experimental crosses between Triatoma lenti Sherlock & Serafim, 1967 and T. sherlocki Papa et al., 2002 (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Infect Genet Evol. 2014;26:123–31.

Rosa JA, Barata JMS, Barelli N, Santos JLF, Belda Neto FM. Sexual distinction between 5th instar nymphs of six species (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87:257–64.

Olaia N, Alevi KCC, Oliveira J, Cacini GL, Souza EDS, Pinotti H, et al. Biology of Chagas disease vectors: biological cycle and emergence rates of Rhodnius marabaensis Souza et al., 2016 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae) under laboratory conditions. Parasitol Res. 2021;120:2939–45.

Monteiro FA, Perez R, Panzera F, Dujardin JP, Galvao C, Rocha D, et al. Mitochondrial DNA variation of Triatoma infestans populations and its implication on the specific status of T. melanosoma. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:229–38.

Guerra AL. Análise molecular do subcomplexo Brasiliensis (Hemiptera, Triatominae); 2016. http://repositorio.unesp.br/handle/11449/136463. Accessed 23 May 2020.

Tartarotti E, Ceron CR. Ribosomal DNA ITS-1 intergenic spacer polymorphism in triatomines (Triatominae, Heteroptera). Biochem Genet. 2005;43:365–73.

Almeida LM, Carareto CMA. Gonadal hybrid dysgenesis in Drosophila sturtevanti (Diptera, Drosophilidae). Ilheringia. 2002;92:71–9.

Alevi KCC, Mendonça PP, Pereira NP, Rosa JA, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV. Karyotype of Triatoma melanocephala Neiva & Pinto (1923). Does this species fit in the Brasiliensis subcomplex? Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1652–3.

De Vaio ES, Grucci B, Castagnino AM, Franca ME, Martinez ME. Meiotic differences between three triatomine species (Hemiptera:Reduviidae). Genetica. 1985;67:185–91.

Monteiro FA, Donnelly MJ, Beard CB, Costa J. Nested clade and phylogeographic analyses of the Chagas disease vector Triatoma brasiliensis in Northeast Brazil. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:46–56.

Neves SJM, Sousa PS, Oliveira J, Ravazi A, Madeira FF, Reis YV, et al. Prezygotic isolation confirms the exclusion of Triatoma melanocephala, T. vitticeps and T. tibiamaculata of the T. brasiliensis subcomplex (Hemiptera, Triatominae). Infect Genet Evol. 2020;79:104149.

Pérez R, Hernández M, Quintero O, Scovortzoff E, Canale D, Méndez L, et al. Cytogenetic analysis of experimental hybrids in species of Triatominae (Hemiptera-Reduviidae). Genetica. 2005;125:261–70.

Díaz S, Panzera F, Jaramillo-O N, Pérez R, Fernández R, Vallejo G, et al. Genetic, cytogenetic and morphological trends in the evolution of the Rhodnius (Triatominae: Rhodniini) trans-andean group. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87493.

Riley R. The secondary pairing of bivalents with genetically similar chromosomes. Nature. 1966;185:751–2.

Alevi KCC, Pinotti H, Araújo RF, Azeredo-Oliveira MTV, Rosa JA, Mendonça VJ. Hybrid collapse confirm the specific status of Triatoma bahiensis Sherlock and Serafim, 1967 (Hemiptera, Triatominae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:475–7.

Nascimento JD, Ravazi A, Alevi KCC, Pardo-Diaz C, Salgado-Roa FC, Rosa JA, et al. Taxonomical over splitting in the Rhodnius prolixus (Insecta: Hemiptera: Reduviidae) clade: are R. taquarussuensis (da Rosa et al., 2017) and R. neglectus (Lent, 1954) the same species? PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211285.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (Process number 2017/05015-7, 2018/12039-2, 2018/24116-1, and 2019/17581-2), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 for financial support.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (Process number 2017/05015-7, 2018/12039-2, 2018/24116-1, and 2019/17581-2), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. JAR: CNPq, PQ-2, process 307 398/2018-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FFM: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review & editing; LGMD: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and data curation; IFB: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and data curation; JO: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, and writing—review & editing; AR: Methodology, investigation, and data curation; YVR: Methodology, investigation, and data curation; ABBO: methodology, investigation, and data curation; DCC: Methodology, investigation and, data curation; CG: Conceptualization, writing—review & editing, and funding acquisition; MTVAO: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing—review & editing; JAR: Conceptualization, resources, and writing—review & editing; KCCA: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Madeira, F.F., Delgado, L.M.G., Bittinelli, I. et al. Triatoma sordida (Hemiptera, Triatominae) from La Paz, Bolivia: an incipient species or an intraspecific chromosomal polymorphism?. Parasites Vectors 14, 553 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04988-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04988-9