Abstract

Background

Babesia bovis is one of the most significant tick-transmitted pathogens of cattle worldwide. Babesia bovis parasites have a complex lifecycle, including development within the mammalian host and tick vector. Each life stage has developmental forms that differ in morphology and metabolism. Differentiation between these forms is highly regulated in response to changes in the parasite’s environment. Understanding the mechanisms by which Babesia parasites respond to environmental changes and the transmission cycle through the biological vector is critically important for developing bovine babesiosis control strategies.

Results

In this study, we induced B. bovis sexual stages in vitro using xanthurenic acid and documented changes in morphology and gene expression. In vitro induced B. bovis sexual stages displayed distinctive protrusive structures and surface ruffles. We also demonstrated the upregulation of B. bovis calcium-dependent protein kinase 4 (cdpk4), tubulin-tyrosine ligase (ttl), and methyltransferase (mt) genes by in vitro induced sexual stages and during parasite development within tick midguts.

Conclusions

Similar to other apicomplexan parasites, it is likely that B. bovis upregulated genes play a vital role in sexual reproduction and parasite transmission. Herein, we document the upregulation of cdpk4, ttl, and mt genes by both B. bovis in vitro induced sexual stages and parasites developing in the tick vector. Understanding the parasite's biology and identifying target genes essential for sexual reproduction will enable the production of non-transmissible live vaccines to control bovine babesiosis.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bovine babesiosis caused by Babesia bovis is one of the most important tick-borne diseases of cattle in tropical and subtropical regions [1]. Babesia bovis is transmitted by Rhipicephalus larval ticks [2, 3]. As the infected larval ticks feed on the vertebrate host, B. bovis sporozoites are inoculated via saliva into the host’s bloodstream [2], where they invade and replicate asexually in red blood cells (RBC) as merozoites [4, 5]. When R. microplus ticks feed on infected animals, they ingest B. bovis-infected erythrocytes. In the midgut of the tick, Babesia undergoes sexual reproduction, which develops into the kinete stage that circulates in tick hemolymph. After kinete invasion of eggs, the parasites are transmitted transovarially [6]. This results in larval progeny containing B. bovis sporozoites that can infect cattle [2].

The clinical signs of bovine babesiosis are characterized by high fever, hemolytic anemia, anorexia, inappetence, hemoglobinuria, and capillary parasite sequestration, leading to death when adult cattle are acutely infected [7]. However, young animals are more resistant to acute infections than adult cattle (> 1 year old). Younger animals’ innate immune system plays an important role in controlling the disease, especially through the clearance of infected erythrocytes in the spleen [6]. Parasites can also establish persistent infections in the absence of obvious clinical signs. These infections lead to inapparent and chronic infections. However, tick transmission of the parasite to other hosts can occur [6].

Babesia bovis transmission relies on the production of sexual stages by responding to environmental signals inside the tick midgut lumen [8]. Disruption of B. bovis development in the tick midgut would prevent transmission via tick vectors. To date, there are no methods to isolate sexual stages from infected tick midgut. We artificially induced B. bovis sexual stage development in in vitro cultures using xanthurenic acid (XA), an intermediate metabolite derived from tryptophan metabolism [9, 10]. In vitro induction of B. bovis sexual stages allowed identifying sexual stage-specific genes and gene families such as the hap2 gene, the cystine motif-rich gene family, and the ccp gene family [10,11,12]. These genes encode proteins that may be important candidates for developing an effective transmission-blocking vaccine to control bovine babesiosis [10,11,12].

In this study, we examined the differential gene expression of B. bovis calcium-dependent protein kinase 4 (cdpk4), tubulin-tyrosine ligase (ttl), and methyltransferase (mt) upon XA induction. Babesia bovis CDPK4, TTL, and MT proteins are homologs to previously identified gamete-specific proteins in Plasmodium falciparum [13] and B. bigemina [14]. We also describe the effect of XA on parasite morphology associated with the development of sexual stages. The present study aimed to understand the basic biology of Babesia parasites and to identify additional sexual stage genes that will enable the development and production of novel Babesia vaccines and possible drug targets to control bovine babesiosis.

Methods

Cattle, ticks, and parasite cultures

A splenectomized 3–4 months male Holstein that tested negative for B. bovis by PCR [2] and cELISA [15] was used in this study. The animal was maintained according to protocols approved by the University of Idaho Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC #2018-16). Rhipicephalus microplus La Minita tick strain [16] was used. Approximately 40,000 larvae from 2 g of eggs were placed under a cloth patch to feed. When approximately 1% of the nymphs molted to adults, the calf was inoculated intravenously with B. bovis S74T3Bo strain stabilate containing approximately 1 × 107 B. bovis-infected erythrocytes [17] to synchronize the peak of parasitemia with female tick repletion. The infected calf was monitored daily for B. bovis in peripheral blood and clinical signs of babesiosis [18] (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Replete female ticks were collected, washed in tap water, dried, and incubated at 26 °C with 93% relative humidity. During the development of B. bovis within the tick midgut, five engorged ticks were removed daily from the incubator and dissected for 6 consecutive days. Individual midgut was placed into 1 ml of TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at − 80 °C. Eleven days post-B. bovis inoculation, infected defibrinated blood was collected from the calf, and the erythrocytes were washed five times with Puck’s saline G to remove white blood cells. Washed infected RBCs were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 rpm, 10 min at 4 °C, and suspended in TRIzol.

Induction of in vitro B. bovis sexual stages

To induce sexual stages, B. bovis infected blood was collected and maintained in in vitro cultures for 1 week before induction. The in vitro cultured B. bovis infected erythrocytes were suspended in a medium with or without 100 μM XA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) as previously described [10]. Induced in vitro sexual stage parasites were isolated at 12 h and 24 h post-induction by differential centrifugation at 400×g for 1 min. The supernatant was recovered and the sexual stages pelleted at 2000×g for 5 min. The sexual stage parasites were suspended in TRIzol and stored at − 20 °C. To estimate cell viability, cells were suspended in PBS, mixed with an equal volume of 20 μg/ml 6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate [19] in PBS (Calbiochem-Behring, La Jolla, CA, USA), and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and visualized by a Leica microscope using LAS-X software.

Scanning electron microscopy

Induced sexual stages were washed three times with PBS. Samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Samples were rinsed twice with distilled water and then post-fixed overnight in 2% osmium tetroxide. After rinsing, parasites were dehydrated with an ethanol series (30–100%). Final drying was with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS). Approximately 50–100 µl of sample suspended in HMDS was pipetted onto a coverslip attached to an aluminum SEM stub and placed in a vacuum desiccator overnight [20] before gold coating. Samples were imaged on a FEI SEM Quanta 200F at Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center, Washington State University.

Transmission electron microscopy

Sexual stage parasites from induced cultures were washed three times with PBS. Samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer and refrigerated overnight at 4 °C. Fixed samples were microwaved in a Pelco Biowave Pro 36500 Laboratory Microwave System for 2 min at 750 Watts, with a temperature cutoff restriction set at 28 °C. Samples were rinsed twice with distilled water and post-fixed overnight in 1% osmium tetroxide at 4 °C. After rinsing, the parasites were dehydrated with an ethanol series (30–100%), then placed into propylene oxide (PO) and infiltrated overnight in a 1:1 PO:Spurr resin mix. Infiltration medium was poured off and changed to 100% Spurr’s embedding media overnight and samples polymerized at 65 °C before thin sectioning (80–100 nm) [21]. Sections were stained sequentially with uranyl acetate, potassium permanganate, and Reynold’s lead before observation with an FEI Tecnai G2 TEM.

In silico target gene identification by genomic search and bioinformatic analysis

To identify B. bovis homologs of P. falciparum and B. bigemina gamete-specific proteins CDPK4, MT, and TTL, bioinformatic analysis was performed based on amino acid identity using NCBI Blastp (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast) and the complete annotated B. bovis genome sequence (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AAXT00000000.2) [22]. Clustal Omega analysis (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) was used to evaluate the percent amino acid identity of proteins. Protein domains conserved among B. bovis, P. falciparum, and B. bigemina homologs were determined using the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). Transmembrane domains were predicted for the target proteins using the Transmembrane Hidden Markov Model Package 2 (TMHMM2) [23] (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0). SignalP-5.0 was used to predict putative signal peptides [24]. Multiple alignments of CDPK4 amino acid sequences from B. bovis, B. bigemina, T. equi, T. parva, and P. falciparum were generated using Multiple Sequence Alignment by CLUSTALW (http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw/). Cello v2.5 predictor was used to predict protein translocation and subcellular localization [25] (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/). Phylogenetic analysis of CDPK4 from B. bovis, B. bigemina, T. equi, T. parva, and P. falciparum was conducted using Phylogeny.fr.software; the tree prediction is based on an approximate likelihood-ratio test (aLRT) as an alternative to nonparametric bootstrap and Bayesian estimation of branch support [26, 27] that used MUSCLE for alignment, Gblocks for curation, PhyML for phylogeny, and TreeDyn for graphic representation.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from blood, induced sexual stages, and tick gut samples using TRIzol reagent according to manufacturer’s protocol and the RNA pellets suspended in 20 µl DEPC-treated water. RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol to remove contaminating genomic DNA, quantified by Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The removal of genomic DNA was confirmed by PCR targeting rap1 as previously described [28] using non-reverse transcribed samples. cDNA was synthesized from 150 ng total RNA of each sample with the Superscript® First-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantitative PCR assay and primer design

To examine the expression pattern of B. bovis cdpk4, mt, ttl, and hap2, specific primers for each gene were designed using the PrimerQuest® Tool (Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT)) (Table 1) following recommended guidelines for qPCR primer design. Primers were purchased from Eurofins Genomics (Louisville, KY, USA). BLASTn analysis confirmed that primer sequences were not contained in the R. microplus genome (NC_023335.1). Melting curve analysis was added to the PCR cycle to check the specificity of each primer pair. Standard PCR was performed to amplify the full-length gene from cDNA samples for all target genes using primers listed in Table 1. PCR cycling conditions consisted of 95 °C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR amplicons were cloned into PCR 2.1-TOPO® (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and submitted for sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon, Louisville, KY). Standard curves were generated for each gene using specific quantities of plasmids. For the normalization of the qPCR data, B. bovis α-tubulin and mitogen-activated protein kinase (mapk) genes were evaluated as parasite reference gene candidates. CFX Manager™ software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) [29] was used to examine the stability of expression of the reference gene candidates. The qPCRs for the genes of interest and reference gene candidates were performed in a CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (C1000 Touch™ Thermal Cycler) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The cycling conditions consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C denaturation for 15 s and annealing at 55 °C for 30 s. Reactions were performed in triplicate in 20 μl using 300 nM of each primer and 2 μl of 1/20 dilution of cDNA as template. qPCR for msa-1 was performed to amplify a 150-bp fragment between bases 604 and 754 of msa-1 (GenBank Accession number AF275911) using msa-1-specific primers, fluorogenic probe, and SsoAdvanced Universal Probes Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) as previously described [2]. A standard curve was developed using dilutions of specific numbers of msa-1 plasmid as previously described [2]. CFX Manager™ software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to analyze the qPCR data. Amplification efficiency was evaluated to determine the sensitivity of the qPCR for each gene. Relative expression was calculated with a division of each gene detected expression by mapk detected expression within each time point. There were heterogeneous variances between time points, and therefore relative expression was transformed to log10. Differences due to time were tested with a mixed linear model with a fixed effect of time and repeated effect of technical replicate. Pairwise differences of time were tested with Tukey or Tukey-Kramer (unbalanced data) adjustment.

Results

Induction and morphological analysis of in vitro B. bovis sexual stages

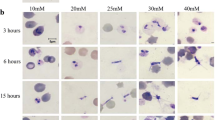

Microscopic inspection of non-induced B. bovis blood stages showed pyriform-shaped parasites in RBC (Fig. 1a). In contrast, B. bovis cultures induced by decreasing temperature to 26 °C and addition of xanthurenic acid to the culture media showed the presence of extra-erythrocytic parasites with long projections and large round parasite stages, indicative of parasite sexual stage formation (Fig. 1b–d). Analysis of XA-induced cultured parasites using scanning electron microscopy showed that egress of in vitro-induced sexual stage parasites from infected RBC began by 3 h after the onset of induction (Fig. 2a). Babesia bovis induced sexual stage cells at 12 h post-XA induction displayed elaborate and distinctive protrusive structures, such as projections and surface ruffles (Fig. 2b–e). Babesia bovis induced sexual stages were found to undergo cell-to-cell fusion, forming multinucleated syncytia, upon XA in vitro induction (Fig. 2f, g). Ultrastructural analysis of induced parasites using transmission electron microscopy showed parasites were mostly rounded or slightly ovoid, exhibiting distinct, unique features that are characteristic of in vitro induced B. bovis sexual stages. Typical Babesia organelles, such as prominent double-membrane nuclei, mitochondria, apicoplasts, spherical bodies, rhoptries and micronemes, vacuoles, and numerous free ribosomes, were observed in extracellular B. bovis sexual stages. Some parasites contained abundant cytoplasmic organelles, while others presented large vacuoles in the cytoplasm. Sequential ultrastructural studies of B. bovis sexual stages showed a pattern of coordinated development of sexual forms, starting with parasite egress from host RBC concomitant with the rupture of the infected RBC membrane (RBCM) observed 3 h after induction (Fig. 3a). The process culminated with parasite cell-to-cell membrane fusion and the formation of multinucleated syncytia (Fig. 3b, c). However, nuclear fusion was not observed.

Scanning electron micrographs of induced in vitro B. bovis sexual stages. a Lysis of the infected red blood cell (iRBC) membrane and release of B. bovis sexual stages (white arrow) from erythrocyte observed 3 h post-induction. b Extracellular B. bovis induced parasite (black arrow) observed 12 h post-induction, c–e Exflagellation of B. bovis sexual stages observed 12 h post-induction. f, g Parasite fusion 24 h post-induction. Scale bar: 2 µm

Transmission electron micrograph of ultrastructural changes in B. bovis upon XA sexual stage induction. The sections were made at time points a 3 h, b 12 h, and c 24 h after addition of XA. N nucleus, FV food vacuole, EP external processes, PPM parasite plasma membrane, M microneme, R rhoptry, EM erythrocyte membrane. The polymerized samples were 80–100 nm thin sections. Scale bar: 500 nm

In silico analysis of target genes

In silico analysis was performed to select B. bovis homologs to previously identified sexual stage genes in P. falciparum (cdpk4, mt, and ttl) and B. bigemina (mt, ttl). In silico predictions suggested the absence of signal peptide and transmembrane domains in B. bovis CDPK4, MT, and TTL proteins. Also, these proteins were found to be cytosolic, consistent with their homologs in P. falciparum [13, 30]. Overall, B. bovis CDPK4, MT, and TTL amino acid sequences appeared well conserved compared with homologs in other species. Accession numbers and functional annotation of B. bovis target proteins are shown (Table 2). Babesia bovis CDPK4 contains a serine/threonine protein kinase, catalytic domain (STKc_CAMK), and an EF-hand type Ca (2+) binding domain (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). Babesia bovis CDPK4 (GenBank: XP_001609485.1) shares 60%, 85%, 77%, and 68% amino acid identity with CDPK4 from P. falciparum (GenBank: XP_001349078.1), B. bigemina (GenBank: XP_012766984.1), T. equi (GenBank: XP_004833801.1), and T. parva (GenBank: XP_766594.1), respectively. Multiple alignments and phylogenetic analysis of amino acid sequences corresponding to the CDPK4 of B. bovis, B. bigemina, T. equi, T. parva, and P. falciparum revealed conservation among apicomplexan parasites (Additional file 3: Fig. S3) consistent with the taxonomic evolution of B. bovis and related apicomplexan species (Additional file 4: Fig. S4). Babesia bovis MT (GenBank: XP_001609901.1) contains a conserved methyltransferase domain (Additional file 2: Fig. S2) that shares 55% amino acid identity with B. bigemina MT (GenBank: XP_012767431.1) and 33% with P. falciparum MT (GenBank: XP_001348700.2). Babesia bovis TTL (GenBank: XP_001611585.1) possesses a tubulin-tyrosine ligase domain (Additional file 2: Fig. S2) and shares 57% amino acid identity with B. bigemina TTL (GenBank: XP_012769325.1) and 27% amino acid identity with P. falciparum gamete-specific protein TTL (GenBank: XP_002808689.1) (Table 3).

Expression of target genes in blood stages, induced sexual stages, and tick midgut-specific stages

Quantitative PCR was used to analyze the transcription pattern of B. bovis cdpk4, mt, and ttl genes in blood from an acutely infected animal, in non-induced culture (0 h), in cultures at 26 °C without or with XA at time points 12 h and 24 h, and in tick-specific stages from individual engorged tick midgut (MG) samples collected from B. bovis infected females. Babesia bovis α-tubulin, mapk transcripts were evaluated as B. bovis reference gene candidates for data normalization (Additional file 5: Table S1). The α-tubulin was considered inadequate for qPCR normalization because it was not stably expressed in the tested parasite stages. In contrast, mapk was stably expressed throughout different time points and the development of tick-specific stages and was selected as a reference gene for normalization. Based on this, the transcription levels of all the target genes were normalized to the mapk expression level. The melt curve analyses showed the absence of primer dimers and nonspecific amplification for all tested genes; the efficiency of amplification ranged between 94 and 109% (Additional file 6: Fig. S5).

The data indicate that cdpk4 gene expression is significantly upregulated in induced sexual stages (induced by decreasing temperature to 26 °C and addition of XA to the culture media) at 24 h (P < 0.0001) and tick-specific stages at days 2 and 6 compared to blood stages (Fig. 4a). In addition, the level of the mt transcript was also increased in induced sexual stages at 24 h (P < 0.0234) and tick-specific stages at days 1 to 6 compared to blood stages (Fig. 4b). However, expression of ttl was higher in induced sexual stages at 12 h (P < 0.0262) and tick-specific stages at days 1, 2, and 6 compared to blood stages (Fig. 4c). Expression of the hap2 gene was found to be upregulated in induced sexual stages at 12 h and 24 h (P < 0.0485) and by tick-specific stages day 2 compared to blood stages (Fig. 4d). Also, hap2 gene expression was previously demonstrated using reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) to be exclusively transcribed by induced sexual stages and during B. bovis development within the tick midgut [10]. Interestingly, msa-1 expression was found to be maximal by blood stages (P < 0.0019) and gradually reduced over time during sexual stage induction and tick-specific stages (Fig. 4e). The results represent the mean of three experiments, each containing three technical replicates (Additional file 7: Table S2). Taken together with the morphological analysis, these results affirmed that XA and a drop-in temperature play an important role during B. bovis sexual stage formation in the in vitro induction system used in these experiments.

Relative expression of B. bovis genes in blood from an acutely infected animal, in non-induced culture (0 h), and cultures at 26 °C without or with XA at time points 12 h and 24 h, and tick-specific stages from individual engorged female tick midgut (MG) samples collected for 6 consecutive days after incubation (MG day1 to day 6). a Calcium-dependent protein kinase 4 (cdpk4). b Methyltransferase (mt). c Tubulin-tyrosine ligase (ttl). d Hapless 2 (hap2). e Merozoite surface antigen-1 (msa-1) genes. The data represent the mean of three experiments, each containing three technical replicates. Asterisk (*) indicates statistical pairwise differences between time points (P < 0.05)

Discussion

In the present study, we examined gene expression and morphology associated with developing sexual stages in induced in vitro cultures and midguts of replete R. microplus fed on B. bovis infected calves. Herein, we extend the number of genes upregulated during B. bovis sexual stage development to include cdpk4, ttl, and mt. CDPK4, a serine/threonine kinase, is an enzyme that plays an important role in intracellular calcium signaling in plants, green algae, ciliates, and apicomplexan parasites [31]. In malaria parasites, CDPK4 is known to be involved in stage-specific cellular responses to calcium signaling transduction pathways, cell cycle regulation, and life cycle progression [32]. In P. berghei male gametocytes, CDPK4 is transcriptionally upregulated [30] and involved in sexual reproduction. Importantly, inhibition of P. falciparum CDPK4 blocked malaria transmission [33,34,35]. Plasmodium falciparum TTL is involved in post-translational C-terminal tyrosination of α-tubulin and regulates the formation of microtubule interacting proteins [13]. Plasmodium falciparum MT plays a fundamental role in gene regulation through the methylation of histones and non-histone proteins such as transcription factors which are essential for parasite development and differentiation [36]. In B. bigemina, MT was identified as a marker of tick stage development [14]. Previous studies demonstrated that differential expression of hap2 [10], the cystine motif-rich gene family [11], and the ccp gene family [12] was associated with apicomplexan sexual stage development. Also, basal B. bovis kinete-specific protein (ksp) expression by blood-stage parasites was found to be upregulated by tick stage parasites [37]. However, KSP protein is restricted to tick stage parasites [37]. These observations suggest that the expression of specific proteins is required for parasite development within the tick vector. The data presented here provide evidence for the importance of cdpk4, ttl, and mt in the development of B. bovis sexual stages [10]. This is supported by our previous work on B. bigemina that found ttl and mt genes were upregulated in sexual stages from tick midgut or induced in vitro culture using tris 2-carboxyethyl phosphine [14]. In P. falciparum, cdpk4, ttl, and mt are upregulated in sexual stages and involved in sexual reproduction and arthropod infection [13, 32, 34, 36, 38]. After B. bovis sexual and zygote formation, parasites develop into kinetes in midgut epithelial cells that migrate to tick hemolymph by day 6 after repletion [37]. Upregulation of B. bovis cdpk4, ttl, and mt expression at day 6 after female tick dropping suggests that these genes may also be important in B. bovis kinete development. This agrees with a recent RNA-seq study that showed all three genes were highly upregulated in B. bovis kinetes [39].

It has been reported that XA is important for in vitro induction of Babesia sexual stages [8, 10, 40]. In malaria, XA is present in the gut of Anopheles mosquitos and is known to induce gametogenesis of P. falciparum [9]. It has recently been shown that XA supported the growth of a tick-borne pathogen, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, in tick cells by inhibition of tryptophan dioxygenase activity [41]. However, it remains unknown whether this metabolite is present in the tick midgut [10]. Babesia bovis sexual stages induced in vitro by XA were observed by light microscopy to have distinct morphological and ultrastructure features similar to those described for B. canis, B. bigemina, and B. bovis sexual stages derived from tick midgut or Boophilus microplus cell cultures [8, 42]. Sexual stages of Babesia are characterized by cytoplasmic projections and microtubule development [8, 10, 43]. Using SEM, we observed aggregation of in vitro induced parasite strahlenkörper forms similar to B. bovis and B. bigemina developing within the tick midgut [8, 44, 45]. This aggregation may improve contact between individuals before the fusion of sexual stages. The close juxtaposition of individuals was confirmed using SEM and TEM, similar to previous work on B. bovis [10].

Further experiments are necessary to investigate the role of B. bovis CDPK4, MT, and TTL proteins during parasite development within the invertebrate host. Knocking out cdpk4, mt, and ttl genes using gene editing and transfection techniques will facilitate determining whether disrupting these genes interferes with the parasite’s life cycle within the tick vector.

Conclusions

Understanding the development of parasite sexual stages is considered a key component of future transmission blocking vaccines and the control of bovine babesiosis. Proteins encoded by the genes described in this study, such as CDPK4, TTL, and MT, might be potential drug or vaccine targets. The current study is a part of our ongoing research to understand B. bovis sexual stage development to design strategies to block parasite transmission.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- ttl :

-

Tubulin tyrosine ligase

- α-tubulin :

-

Alpha tubulin

- cdpk4 :

-

Calcium-dependent protein kinase 4

- mapk :

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mt :

-

Methyltransferase

- msa-1 :

-

Merozoite surface antigen-1

- hap2 :

-

Hapless 2

- XA:

-

Xanthurenic acid

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell

- niRBC:

-

Non-infected red blood cell

- RBCM:

-

Red blood cell membrane

- ISS:

-

Induced sexual stages

- TCEP:

-

Tris 2-carboxyethyl phosphine

- bp:

-

Base pair

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

References

Bock R, Jackson L, de Vos A, Jorgensen W. Babesiosis of cattle. Parasitology. 2004;129(Suppl):S247–69.

Howell JM, Ueti MW, Palmer GH, Scoles GA, Knowles DP. Transovarial transmission efficiency of Babesia bovis tick stages acquired by Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus during acute infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:426–31.

Jonsson NN, Davis R, De Witt M. An estimate of the economic effects of cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) infestation on Queensland dairy farms. Aust Vet J. 2001;79:826–31.

Gaffar FR, Yatsuda AP, Franssen FFJ, de Vries E. Erythrocyte invasion by Babesia bovis merozoites is inhibited by polyclonal antisera directed against peptides derived from a homologue of Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1. Infect Immun. 2004;72:47–55.

Dubremetz JF, Garcia-Réguet N, Conseil V, Fourmaux MN. Apical organelles and host-cell invasion by Apicomplexa. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:1007–13.

Florin-Christensen M. Pursuing effective vaccines against cattle diseases caused by apicomplexan protozoa. CAB Rev Perspect Agric Vet Sci Nutr Nat Resour. 2021;16:024.

Suarez CE, Laughery JM, Schneider DA, Sondgeroth KS, McElwain TF. Acute and persistent infection by a transfected Mo7 strain of Babesia bovis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2012;185:52–7.

Mosqueda J, Falcon A, Antonio Alvarez J, Alberto Ramos J, Oropeza-Hernandez LF, Figueroa JV. Babesia bigemina sexual stages are induced in vitro and are specifically recognized by antibodies in the midgut of infected Boophilus microplus ticks. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1229–36.

Billker O, Lindo V, Panico M, Etienne AE, Paxton T, Dell A, Rogers M, Sinden RE, Morris HR. Identification of xanthurenic acid as the putative inducer of malaria development in the mosquito. Nature. 1998;392:289–92.

Hussein HE, Bastos RG, Schneider DA, Johnson WC, Adham FK, Ueti MW, et al. The Babesia bovis hap2 gene is not required for blood stage replication, but expressed upon in vitro sexual stage induction. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005965.

Alzan HF, Lau AOT, Knowles DP, Herndon DR, Ueti MW, Suarez CE, et al. Expression of 6-Cys Gene superfamily defines Babesia bovis sexual stage development within Rhipicephalus microplus. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0163791.

Bastos RG, Suarez CE, Laughery JM, Johnson WC, Ueti MW, Knowles DP. Differential expression of three members of the multidomain adhesion CCp family in Babesia bigemina, Babesia bovis and Theileria equi. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67765.

Florens L, Washburn MP, Raine JD, Anthony RM, Grainger M, Tabb DL, et al. A proteomic view of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. Nature. 2002;419:520–6.

Bohaliga GAR, Johnson WC, Taus NS, Hussein HE, Bastos RG, Ueti MW, et al. Identification of a putative methyltransferase gene of Babesia bigemina as a novel molecular biomarker uniquely expressed in parasite tick stages. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:480.

Goff WL, Molloy JB, Johnson WC, Suarez CE, Pino I, Adams DS, et al. Validation of a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibodies against Babesia bovis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:1212–6.

Stiller D, Goff WL, Johnson LW, Knowles DP. Dermacentor variabilis and Boophilus microplus (Acari: Ixodidae): experimental vectors of Babesia equi to equids. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:667–70.

Goff WL, Johnson WC, Cluff CW. Babesia bovis immunity. In vitro and in vivo evidence for IL-10 regulation of IFN-gamma and iNOS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;849:161–80.

Bastos RG, Ueti MW, Guerrero FD, Knowles DP, Scoles GA. Silencing of a putative immunophilin gene in the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus increases the infection rate of Babesia bovis in larval progeny. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2:57.

Goff WL, Davis WC, Palmer GH, McElwain TF, Johnson WC, McGuire TC, et al. Identification of Babesia bovis merozoite surface antigens by using immune bovine sera and monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2363–8.

Fischer ER, Hansen BT, Nair V, Hoyt FH, Dorward DW. Scanning electron microscopy. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2012;CHAPTER:Unit2B.2–Unit2B.2.

Burghardt RC, Droleskey R. Transmission electron microscopy. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2006;3:2B.1.1-2B.1.39.

Brayton KA, Lau AO, Herndon DR, Hannick L, Kappmeyer LS, Fadrosh D, et al. Genome sequence of Babesia bovis and comparative analysis of apicomplexan hemoprotozoa. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1401–3.

Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–80.

Almagro Armenteros JJ, Tsirigos KD, Sønderby CK, Petersen TN, Nielsen H, et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:420–3.

Yu CS, Chen YC, Lu CH, Hwang JK. Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Proteins. 2006;64:643–51.

Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Lescot M, et al. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–9.

Dereeper A, Audic S, Claverie JM, Blanc G. BLAST-EXPLORER helps you building datasets for phylogenetic analysis. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:8.

Figueroa JV, Chieves LP, Johnson GS, Buening GM. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction based assay for the detection of Babesia bigemina, Babesia bovis and Anaplasma marginale DNA in bovine blood. Vet Parasitol. 1993;50:69–81.

Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, Speleman F, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:Research0034.

Billker O, Dechamps S, Tewari R, Wenig G, Franke-Fayard B, Brinkmann V. Calcium and a calcium-dependent protein kinase regulate gamete formation and mosquito transmission in a malaria parasite. Cell. 2004;117:503–14.

Billker O, Lourido S, Sibley LD. Calcium-dependent signaling and kinases in apicomplexan parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:612–22.

Ghartey-Kwansah G, Yin Q, Li Z, Gumpper K, Sun Y, Yang R, Wang L, et al. Calcium-dependent protein kinases in malaria parasite development and infection. Cell Transplant. 2020;29:0963689719884888.

Ojo KK, Pfander C, Mueller NR, Burstroem C, Larson ET, Murphy RC, et al. Transmission of malaria to mosquitoes blocked by bumped kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2301–5.

Ojo KK, Eastman RT, Vidadala R, Zhang Z, Rivas KL, Hulverson MA, et al. A specific inhibitor of PfCDPK4 blocks malaria transmission: chemical-genetic validation. J infect Dis. 2014;209:275–84.

Choi R, Michaels SA, Onu EC, Hulverson MA, Saha A, Ojo KK, et al. Taming the boys for global good: contraceptive strategy to stop malaria transmission. Molecules. 2020;25:2773.

Bobenchik AM, Witola WH, Augagneur Y, Nic Lochlainn L, Garg A, Lee A, et al. Plasmodium falciparum phosphoethanolamine methyltransferase is essential for malaria transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:18262–7.

Johnson WC, Taus NS, Reif KE, Bohaliga GAR, Kappmeyer LS, Ueti MW. Analysis of stage-specific protein expression during Babesia bovis development within female Rhipicephalus microplus. J Proteome Res. 2017;16:1327–38.

Fang H, Klages N, Baechler B, Hillner E, Yu L, Brochet M, et al. Multiple short windows of calcium-dependent protein kinase 4 activity coordinate distinct cell cycle events during Plasmodium gametogenesis. Elife. 2017;6:e26524.

Ueti MW, Johnson WC, Kappmeyer LS, Herndon DR, Mousel MR, Suarez CE, et al. Comparative analysis of gene expression between Babesia bovis blood stages and kinetes allowed by improved genome annotation. Int J Parasitol. 2021;51:123–36.

Camacho-Nuez M, Hernández-Silva DJ, Castañeda-Ortiz EJ, Paredes-Martínez ME, Rocha-Martínez MK, Mosqueda J, et al. Hap2, a novel gene in Babesia bigemina is expressed in tick stages, and specific antibodies block zygote formation. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:568.

Dahmani M, Anderson JF, Sultana H, Neelakanta G. Rickettsial pathogen uses arthropod tryptophan pathway metabolites to evade reactive oxygen species in tick cells. Cell Microbiol. 2020;22:e13237.

Mehlhorn H, Schein E, Voigt WP. Light and electron microscopic study on developmental stages of Babesia canis within the gut of the tick Dermacentor reticulatus. J Parasitol. 1980;66:220–8.

Nguyen TT, Dang-Trinh MA, Higuchi L, Mosqueda J, Hakimi H, Asada M, Yamagishi J, Umemiya-Shirafuji R, Kawazu SI. Initiated Babesia ovata sexual stages under in vitro conditions were recognized by anti-CCp2 antibodies, showing changes in the DNA content by imaging flow cytometry. Pathogens. 2019;8:104.

Golgh JM, Jorgensen WK, Kemp DH. Development of tick gut forms of Babesia bigemina in vitro. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1998;45:298–306.

Chauvin A, Moreau E, Bonnet S, Plantard O, Malandrin L. Babesia and its hosts: adaptation to long-lasting interactions as a way to achieve efficient transmission. Vet Res. 2009;40:37.

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul Lacy for excellent technical assistance in maintaining B. bovis cultures and thank Kathleen Mason, James Allison, Ralph Horn and Megan Blauert of the US Department of Agriculture, Animal Disease Research Unit, for their excellent animal care, and tick colony maintenance. We thank Sara Davis for her technical assistance. We thank Valerie Lynch-Holm, and Daniel Leroy Mullendore at the Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, for their technical assistance with the scanning and transmission electron microscopy.

Funding

This work was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service Project no. 2090-32000-039-00D and by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (grant no. 2020-67030-31476/project accession no. 1021184) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HEH, MRM, WCJ, and MWU designed the study. HEH, WCJ, JCP, and MWU performed the experiments. HEH, WCJ, NST, CES, MRM, and MWU performed the data analysis. HEH, WCJ, and MWU drafted the manuscript. HEH, WCJ, NST, JCP, CES, MRM, and MWU read and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Protocol Committees of the University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho, in accordance with institutional guidelines based on the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Clinical signs of B. bovis infection. a: Calf packed cell volume (PCV) and temperature recorded after B. bovis inoculation and during the tick feeding period. b: Giemsa-stained blood smear at day 11 after parasite inoculation showing B. bovis iRBC.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2.

Schematic representation of the location and number of functional domains in upregulated sexual stage genes. Babesia bovis calcium-dependent protein kinase 4 (CDPK4) had N-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain (S_TKc) and a C-terminal calmodulin-like domain with four EF hand motifs (EF); B. bovis methyltransferase (MT) had a methyltransferase domain (MT), and B. bovis tubulin tyrosine ligase (TTL) had a tubulin-tyrosine ligase domain (TTL).

Additional file 3: Fig. S3.

Multiple alignment of amino acid sequences corresponding to the CDPK4 of B. bovis (GenBank: XP_001609485.1), B. bigemina (GenBank: XP_012766984.1), T. equi (GenBank: XP_012766984.1), T. parva (GenBank: XP_766594.1), and P. falciparum (GenBank: XP_001349078.1). Stars correspond to a high level of conservation between species.

Additional file 4: Fig. S4.

Phylogenetic tree based on CDPK4 amino acid sequences from B. bovis (GenBank: XP_001609485.1), B. bigemina (GenBank: XP_012766984.1), T. equi (GenBank: XP_012766984.1), T. parva (GenBank: XP_766594.1), and P. falciparum (GenBank: XP_001349078.1). CDPK4 sequence from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (GenBank: XP_001693482.1) was used as outgroup for phylogenetic rooting.

Additional file 5: Table S1.

Expression of B. bovis reference gene candidates during development of blood stages, sexual stages from in vitro induced parasites and tick midgut stages.

Additional file 6: Fig. S5.

Standard curves of qRT-PCR assays designed for B. bovis genes. a: Calcium-dependent protein kinase 4 (cdpk4), b: methyltransferase (mt), c: tubulin-tyrosine ligase (ttl), d: mitogen-activated protein kinase (mapk), and e hap2. The figure shows standard curves obtained using tenfold dilutions of the construct prepared for each target gene and the reference gene mapk diluted from 107 to 102.

Additional file 7: Table S2.

Expression of B. bovis genes essential for sexual stage development.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hussein, H.E., Johnson, W.C., Taus, N.S. et al. Differential expression of calcium-dependent protein kinase 4, tubulin tyrosine ligase, and methyltransferase by xanthurenic acid-induced Babesia bovis sexual stages. Parasites Vectors 14, 395 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04902-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04902-3