Abstract

Background

The incidence of Lyme borreliosis varies over time and space through as yet incompletely understood mechanisms. In Europe, Lyme borreliosis is caused by infection with a Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) genospecies, which is primarily transmitted by a bite of Ixodes ricinus nymphs. The aim of this study was to investigate the spatial and temporal variation in nymphal infection prevalence of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) (NIP), density of questing nymphs (DON) and the resulting density of infected nymphs (DIN).

Methods

We investigated the infection rates in I. ricinus nymphs that were collected monthly between 2009 and 2016 in 12 locations in the Netherlands. Using generalized linear mixed models, we explored how the NIP, DON and DIN varied during the seasons, between years and between locations. We also determined the genospecies of the Borrelia infections and investigated whether the genospecies composition differed between locations.

Results

The overall NIP was 14.7%. A seasonal pattern in infection prevalence was observed, with higher estimated prevalences in the summer than in the spring and autumn. This, combined with higher nymphal densities in summer, resulted in a pronounced summer peak in the estimated DIN. Over the 7.5-year study period, a significant decrease in infection prevalence was found, as well as a significant increase in nymphal density. These two effects appear to cancel each other out; the density of infected nymphs, which is the product of NIP × DON, showed no significant trend over years. Mean infection prevalence (NIP, averaged over all years and all months) varied considerably between locations, ranging from 5 to 26%. Borrelia genospecies composition differed between locations: in some locations almost all infections consisted of B. afzelii, whereas other locations had more diverse genospecies compositions.

Conclusion

In the Netherlands, the summer peak in DIN is a result of peaks in both NIP and DON. No significant trend in DIN was observed over the years of the study, and variations in DIN between locations were mostly a result of the variation in DON. There were considerable differences in acarological risk between areas in terms of infection prevalence and densities of ticks as well as in Borrelia genospecies composition.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lyme disease, or Lyme borreliosis, is the most prevalent tick-borne infection of humans in the northern hemisphere. In western Europe, its causative bacterial agent, Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) (referred to as Borrelia hereafter), and its vector, the caster bean tick Ixodes ricinus, are widespread. A Europe-wide meta-analysis on Borrelia prevalence found an average prevalence of 5.9% in I. ricinus nymphs in western Europe [39]. In the Netherlands, both Ixodes ricinus and the Borrelia spirochaete have been found in various habitats across the country and to vary considerably in space [6, 13, 43]. A study conducted between 2000 and 2004 found significant differences between four study habitats (heather, forest, city park and dunes) and between years, with Borrelia prevalence ranging from 0.8 to 11.5% [43]. Analysis of the first 1.5 and 5 years of the current study yielded estimates for the mean prevalence per location of between 0 and 29% and 7 to 26%, respectively [13, 40].

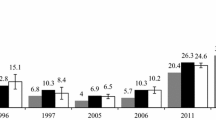

In the last few decades, the number of reported tick bites and the incidence of erythema migrans (an early sign of Lyme borreliosis) reported by general practitioners in the Netherlands have increased sharply [18, 19] (see also Tekenradar 2020 [42]). This could partly be a result of increasing awareness among general practitioners and the general public, but there are also indications that the number of ticks is increasing as well [37]. The risk of acquiring Lyme disease depends on many different factors, of which the most important are the abundance of questing I. ricinus ticks infected with Borrelia [24] and the level of human exposure to ticks [21, 44]. Therefore, a proper understanding of the spatial and temporal variation in risk of being bitten by an infected tick is necessary for effectively informing the public, so that people know when and where preventive measures should be implemented. Examples of preventive measures include checking for tick bites after outdoor activities, wearing tick-repelling clothes and/or avoiding certain areas at certain times of the year altogether.

Since I. ricinus nymphs are responsible for most bites on humans, the risk of acquiring an infected tick bite during a given activity is largely determined by the density of infected nymphs (DIN) [8, 10, 24]. The DIN is therefore also referred to as the acarological risk of exposure to tick-borne pathogens [10, 27, 40]. The DIN is determined by the density of questing nymphs (DON) and the nymphal infection prevalence (NIP). The DON can be considered to be a proxy for the probability of acquiring a tick bite, whereas the NIP can be regarded as an estimate of the probability that the bite is from an infected tick.

Within the framework of the Dutch phenological citizen science programme Nature’s Calendar, nymphs were collected monthly by well-trained volunteers at 12 locations throughout the Netherlands for a period of 10 years [13, 15, 40]. For the period 2009–2016, captured nymphs were screened for the presence of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). This longitudinal dataset, consisting of 7.5 years of prevalence data, allowed us to determine the spatial and temporal variation in Borrelia NIP, the specific B. burgdorferi genospecies, the DON and the DIN.

We determined the B. burgdorferi genospecies for the infected nymphs when possible. Different genospecies have been associated with different manifestations of Lyme borreliosis; for example Borrelia afzelii is mostly associated to erythema migrans, whereas B. garinii has been associated with Lyme neuroborreliosis [7, 38]. Since the genospecies are also associated with different reservoir hosts (B. afzelii with small mammals and B. garinii and B. valaisiana with bird species)[23] and locations are likely to differ in their vertebrate species composition, we investigated whether Borrelia genospecies composition differed between locations.

Materials and methods

Tick collection

Nymphs were collected by well-trained volunteers at 12 locations in the Netherlands. The sampling was part of the above-mentioned Nature’s Calendar project and has been described in detail elsewhere [13, 15, 40]. Details on the 12 sampling locations can be found in Appendix A, and a map is shown in Fig. 1. Each location was sampled once a month by dragging a white cotton cloth (1 m2) along two marked 100-m-long transects; thus, the total sampled area per location was 200 m2 per session. The cloth was inspected for ticks at intervals of 25 m. All larvae, nymphs and adult ticks that had attached to the cloth were counted and collected at each interval. Upon arrival in the laboratory, the ticks were identified by an experienced technician using morphological keys as described in [1] and [17]. All captured ticks were I. ricinus. In this analysis, we included nymphs collected between January 2009 and June 2016, as nymphs collected before January 2009 were screened for Borrelia infections with a different method. In total, 26,658 nymphs have collected since January 2009. The maximum number of nymphs to be tested per sampling session was set at 30 (or 60 in later years); in total, 14,910 nymphs were tested.

Testing for Borrelia

Only nymphal ticks were examined for the presence of Borrelia DNA. If on any sampling day and site fewer than 30 nymphs were collected, all ticks were examined; if more than 30 nymphs were found, a random sample of approximately 30 specimens collected at that site was selected for Borrelia analysis. For all samples, DNA was extracted by alkaline hydrolysis [14]. DNA extracts were stored at − 20 °C until further use. For the detection of Borrelia DNA, a duplex qPCR was used, based on the detection of fragments of the outer surface protein A (ospA) and flagellin genes [16]. DNA from the samples that were qPCR-positive were amplified by conventional PCR that targeted the 5S–23S ribosomal RNA intergenic spacer region of B. burgdorferi as described [5]. In short, we used the forward primer B5Sborseq (5′-GAGTTCGCGGGAGAGTAGGTTATTGCC-3′) and the reverse primer 23Sborseq (5′-TCAGGGTACTTAGATGGTTCACTTCC-3′). To check whether a product was obtained from the PCR, 8-μl aliquots of the PCR mixture were electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel containing an electrophoretic color marker (SYBR™ Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain; Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA, USA). If the PCR was successful and a clear band was visible on the gel, the DNA was cleaned with ExoSAP-IT™ PCR Product Cleanup Reagent (Applied Biosystems™, Foster City, CA, USA) and sent for sequencing at the commercial laboratory BaseClear BV (Leiden, the Netherlands). The chromatographs of the sequences were visually inspected and the primers sites trimmed in Bionumerics version 7.4 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). These sequences were used to identify the B. burgdorferi (s.l.) genospecies by comparison to sequences of known genospecies from GenBank. The cluster analyses and genospecies determination were also performed in Bionumerics version 7.4 (Applied Maths) exactly as described previously [5].

Statistical analysis of the NIP, DON and DIN

For the analysis of the NIP, DON and DIN, all data were used, except for the observations from Vaals between December 2013 and June 2016, where the sampling effort had changed due to one of the transects not being sampled in this period. As a result, 465 nymphs (359 were tested of which 44 were positive for Borrelia) were omitted, leaving 26,193 nymphs (14,551 were tested, of which 2151 were positive for Borrelia) for the analysis. For each sampling session (that is, each specific combination of location, month and year), the NIP was calculated as the number of Borrelia-positive nymphs divided by the number of tested nymphs. The DON is the total number of nymphs collected at a session, and the DIN is calculated as the NIP multiplied by the DON (which for sessions in which all nymphs were tested is the same as the number of collected nymphs that were Borrelia positive). Both DON and DIN are expressed as the number of ticks per 200 m2 of sampled area. All analyses were performed in R version 3.2.5 [30].

We used generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) to analyse how the NIP, DON and DIN depend on the year, month and location using different models for each of these tick parameters. GLMMs were selected because these models can handle non-normally distributed data, such as count data, as well as (multiple) random effects. We used the glmmTMB package [2], which handles beta-binomial and negative binomial distributions as well as crossed and nested random effects. For the NIP we assumed a beta-binomial distribution, and a logit link function. For the DON and DIN, we used a negative binomial distribution with a log link.

We included the variables Location, Year and Month as fixed effects. Locations within Year were included as random effect (1 | YearF:LocF) to account for the fact that observations from the same year–location combination are not independent. With the drop1() function, we dropped single terms into the model one by one to see whether the variables Location, Year and Month had any predictive power in the model. Estimated marginal means were calculated for each month, year and location, using the emmeans package [22]. Estimated marginal means should be interpreted as predicted averages over all factors (based upon the fitted model), so the estimated marginal mean NIP for a specific month was averaged over all years and all locations. We also tested for (linear) trends over the years by running the GLMM models with year as numerical fixed factor.

Analysis of genospecies

For the analysis of the variation in genospecies composition, data from all locations and all years were used. The analysis was performed on the 1298 infected nymphs from which the genospecies was determined. The distribution over the different genospecies was plotted in pie charts, both for all locations together and for separate locations.

Results

NIP, DON and DIN

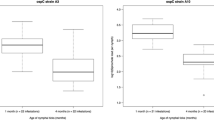

Of the 14,910 tested nymphs, 2195 were found to be positive for Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) Therefore, the overall prevalence in this study was 14.7%. Dropping the single fixed terms into the model one by one using the drop1() function yielded significant effects (α = 0.05) for Year, Location and Month for each of the three outcome variables, indicating that there is spatial and temporal variation in NIP, DON and DIN. The estimated marginal means for the NIP, DON and DIN are shown for each of the months, years and locations in Fig 2. We present the results for seasonal variation (between-month variation), temporal variation over years and spatial variation (between locations) separately. The raw data for NIP, DON and DIN (calculated as the product of NIP × DON) are presented per year and location (Appendix B) and per season and location (Appendix C).

Estimated marginal means for nymphal infection prevalence (NIP), density of nymphs (DON) and density of infected nymphs (DIN) for the different months, years and locations of the study. The x-axes of the graphs for the locations (lower three panels) were sorted based on the prevalence values. Code for the locations is given in caption to Fig. 1

Seasonal variation

The NIP shows a seasonal pattern, with a gradual increase in prevalence from March to August and a decrease after August. In a pairwise comparison, the estimated marginal means for March (9.7%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 7.3–12.8%) and August (16.1%; 95% CI 14.0–18.5 %) differed significantly (p = 0.032); all other comparisons yielded p values > 0.05 (although for March–June, March–September, April–June and April–August they were < 0.10). In the winter months, prevalence seems to be higher than in spring, but these estimates are based on a very limited number of nymphs captured (and tested) and they are therefore less reliable. The DON shows a clear unimodal pattern, with a steep increase between March and June, and a decrease from June to winter. The DIN shows a very similar pattern, but due to the NIP peak being slightly later than the DON peak, the peak in DIN is more symmetrical than that in the DON; that is, the DON is higher in May than in August, but since NIP peaks in August, the DIN values in May and August become similar.

Temporal variation over years

A significant decreasing trend in NIP was observed over the 7.5 years of the study period (p < 0.001). The overall estimated odds ratio for year is 0.92, which means that the odds of the tick being infected with Borrelia in 1 year is 0.92-fold the odds in the previous year. A significant increasing trend in the DON over the study years was also observed (p < 0.01), with an estimated ratio between the DON in 1 year and the preceding year of 1.07. The DIN, which is the resulting variable of the latter two, does not show a trend (p = 0.10). We checked if this pattern was the same for all individual locations. For several locations, the model did not converge, but for the locations where we had estimates, the trends are similar to the overall trend, with the exception of Ede, Dronten and Hoog Baarlo, where the DIN shows a significant negative trend (Table 1; see Appendix E for more detailed results).

Spatial variation

The estimated marginal means (averaged over year and months) of NIP, DON and DIN vary substantially between locations (see three lower panels of Fig. 2). The estimated mean NIP varied between 5% (95% CI 4.0–7.3%) in Hoog Baarlo and 26% (95% CI 21.0–32.5%) in Dronten. The results of a pairwise comparison of the NIP values between the locations show that Hoog Baarlo has a significantly lower NIP than most locations and Dronten has a significantly higher NIP (Appendix F). There are also considerable differences in DON between the locations. The DIN values show a very similar pattern to the DON values; locations with high DON values (Gieten, Veldhoven and Wassenaar) also have high DIN values and, vice versa, locations with low DON values have low DIN values (Schiermonnikoog, Bilthoven and Vaals); the same applies to intermediate DON/DIN values (Ede, Montferland and Twiske). In cases of low (Hoog Baarlo) or high values of NIP (Kwade Hoek and Dronten), the DIN is lower and higher, respectively, than would be predicted just from the DON. We quantified how much of the variation in DIN between locations was attributable to variation in NIP and DON, respectively, by comparing the effect sizes. The effect size of (standardized) DON was approximately twice as high as the effect size of (standardized) NIP, which indicates that the value of the DIN is to a large extent determined by the DON.

Genospecies

Of the 2195 Borrelia-infected nymphs, genospecies was determined for 1298 infected nymphs. For the remaining nymphs, either no attempt was made to determine the genospecies (505 infected nymphs collected between January 2010 and June 2011) or the genospecies could not be determined (392 nymphs).

Of of the 1298 nymphs for which the genospecies of the Borrelia was determined, the large majority were found to be infected with B. afzelii (972 nymphs, 74.9%) (see Fig. 3). The other genospecies were B. garinii (167 nymphs, 12.9%), B. valaisiana (97 nymphs, 7.5%), Borrelia (s.s.) (54 nymphs, 4.2%), and B. spielmanii (only 7 nymphs, 0.5%). Borrelia turdi was found only once (0.05%) (not shown in Fig. 3). In four locations, > 90% of the tick infections were of the genotype B. afzelii (Kwade Hoek, Twiske, Veldhoven and Wassenaar) (Appendix D). In Vaals, the genospecies composition was highly diverse, with 33% B. afzelii, 28% Borrelia (s.s.), 25% B. garinii, 11% B. valaisiana, 2% B. spielmanii and 1% B. turdi. In the other seven sampling locations, B. afzelii was dominant (between 55 and 70%), but the combined percentages of B. garinii, B. valaisiana, and in some cases B. burgdorferi (s.s.) comprised at least 30% of the genospecies present. Temporal trends were not assessed because the number of infections with specific genospecies per location was too low.

Discussion

In this study, based on monthly data collected from 12 sampling locations throughout the Netherlands over a 7.5-year period, 2195 of the 14,910 nymphs assayed were found to be positive for B. burgdorferi (s.l.). The overall NIP (i.e., the overall percentage of all tested nymphs regardless of year, month and location) was thus 14.7%. We found marked differences in prevalence through the season, over time and between locations.

The 14.7% prevalence in nymphs is in line with previous findings from a meta-analysis for B. burgdorferi (s.s.) prevalence in questing nymphs in Europe, where the prevalence was estimated at 12.3, 14.6 or 15.4%, depending on whether the detection was done with PCR, nested PCR or qPCR, respectively [39]. Our findings are in line with reported prevalences in the neighbouring country Belgium, where studies reported estimates for the prevalence of Borrelia in nymphs of 15.6% [34] and in ticks of 12% [20]. However, it is higher than the mean Borrelia infection prevalence of 5.9% that was reported for nymphs in western Europe (defined here as Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) in the meta-analysis by Strnad and colleagues [39].

Our study revealed a striking seasonal pattern in prevalence, with the NIP steadily increasing between March and August, and decreasing afterwards. In the winter months, the prevalence also appears to be higher as well, but due to low numbers of captured nymphs, these estimates are very uncertain. Information on the seasonal trends in other locations is scarce; studies on the seasonality of questing tick activity often present a single overall estimate for the Borrelia infection prevalence (for example, see [9, 28, 36]. Our finding of an increase between spring and summer is in concordance with findings in southern Germany, where nymphal infection prevalence was found to rise from 9.3% in the spring to 16.1% in the summer [11]. In Sweden and Norway, different patterns have been observed, with higher prevalences in late spring and early summer, compared to late summer and autumn [25, 41]. A study in France on 461 questing nymphs found no differences throughout the year [29], but that may be linked to the limited study size. A study in southwestern Slovakia reported that the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens followed the same pattern as that of tick questing activity, namely a bimodal seasonal pattern with a peak in April and May and another one in July [4]. However, this latter study reports the relative prevalence, which is the proportion of positive ticks for the given pathogen during a certain month divided by the total number of collected ticks over the whole period, not the monthly prevalence as used in our study. A study in Luxembourg reported a bimodal seasonal activity beginning with high numbers of Borrelia infections in ticks in May and a second peak in September. This study, conducted between May and October, was based on 157 infected nymphs of a total of 1394 nymphs and adult ticks [32]. Our study, which reports year-round monthly values for the NIP during a period of 7.5 years and which is based on almost 15,000 tested nymphs (of which 2195 tested positive for Borrelia) provides a unique opportunity to study the seasonality of Borrelia prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus nymphs in such detail. As possible mechanisms underlying the seasonal trend in infection prevalence in questing nymphs, we speculate that seasonality in host availability (e.g. rodent populations are strongly seasonal, with lower numbers in winter) or seasonality in the Borrelia prevalence in hosts may play a role. The latter would in turn be an effect of seasonality in infected tick bites and host immunity, so cause and effect cannot easily be distinguished. It could also be that infection with Borrelia affects the activity levels [12], so that infected nymphs may quest more in winter (which would explain the non-significant higher infection prevalence in winter), possibly leading to depletion of their energy and lower survival through the winter. More information on infection prevalences in host species and on survival in infected and non-infected ticks is needed before we can draw any conclusions on which mechanisms play a role here.

The overall temporal trend over the years for Borrelia prevalence in our 7.5-year study period was negative; the NIP decreased slightly between 2009 and 2016 in these 12 locations. By contrast, the density of questing nymphs (DON) increased over the same period. The density of infected nymphs (DIN), which is the product of NIP × DON per session, showed no significant overall trend over the years due to the decrease in NIP and the increase in DON cancelling each other out. In three specific locations, Ede, Hoog Baarlo and Dronten, the DIN decreased significantly. In none of the study locations was a significant increase in DIN observed over the study period. Okeyo et al. [26] studied NIP in the summer period in Latvia and reported a decrease in NIP over the period 1999–2010 (note that the study period differs from the period in our study).

We argue that both NIP and DIN are important measures of risk: NIP is a proxy for the probability that, given a tick bite, one gets infected, whereas the DIN represents a proxy for the probability to get an infected tick bite. A concrete example is as follows: at the transects in Dronten, the chance of getting an infectious tick bite was comparatively low, but once you do get bitten there, the probability of acquiring an infection was high. Other aspects of risk, such as accessibility of the area, contact chance between visitors and tick vantage points, the awareness of the public, among others were not considered in this analysis, but will most certainly also play a role in determining risk profiles.

We also assessed what contributes most to the variation in the DIN: variation in the DON or variation in the NIP. We found that the DIN is mostly determined by the DON, especially when examining variation throughout the season: the reason that the DIN shows a clear seasonal peak is mostly a result of the seasonal peak in DON. Differences in DIN between locations are also mostly a result of differences in DON. This finding is in line with that of Tälleklint and Jaenson [41], who suggested that within a certain range of nymphal densities, it may be possible to assess the density of Borrelia-infected I. ricinus nymphs without examining nymphs for the presence of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) [41].

Spatial variation in NIP was substantial during our study period, with estimated prevalence ranging between 5% (in Hoog Baarlo) and 26% (in Dronten). This spatial variation did not coincide with differences in general landscape/habitat characteristics; of the five locations with similar forest type, that is mixed forest with birch and oak with rich understorey (Ede, Hoog Baarlo, Gieten, Montferland and Veldhoven), NIP values at Hoog Baarlo were significantly lower than those at the other locations. Hoog Baarlo, the location with the lowest prevalence among all sampling locations, is also the only location with a population of red deer. Although we cannot draw strong conclusions based on a single location, this finding is in line with reports from previous studies. A study along the West coast of Norway found lower prevalences of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) in questing I. ricinus nymphs in areas of high red deer density [25]. The findings of another study in Norway, on Norwegian islands, also suggests that high abundances of roe deer and red deer may reduce the infection rate of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) in host-seeking I. ricinus [33].

The locations with the highest prevalences were also diverse in terms of vegetation type: the site in Wassenaar is a pine forest near the dunes, whereas Veldhoven is an inland mixed oak–birch forest, and Dronten is situated on reclaimed land and has a mixed of willow and oak in one transect and beech, common alder and sycamore maple in the other. This shows that high prevalences of Borrelia can be sustained in several different habitat types.

In all locations, B. afzelii was the most prevalent genospecies. Overall, 75% of the infected nymphs was infected with this genospecies. In four locations, B. afzelii comprised > 90% of the infections. In seven locations, B. afzelii was the dominant genospecies (55–70%), but B. valaisiana, B. garinii and sometimes B. burgdorferi (s.s.) also comprised at least 30% genospecies present. In Vaals, the genospecies distribution was more even, with almost equal contributions from B. afzelii, B. burgdorferi (s.s.) and B. garinii. The genospecies composition is likely to be a result of the local composition of the host animals. Unfortunately, these have not been recorded in this study. Compared to other studies, our study reports a higher percentage of infections with B. afzelii. In several European studies, B. afzelii has been reported to be the most prevalent genospecies, but often the B. afzelii infections comprised a smaller fraction of the total. A recent meta-analysis reported 45% of infected questing ticks to be infected with B. afzelii in western Europe, and percentages of 29% for B. garinii, 17% for B. valaisiana and 6% for B. burgdorferi (s.s.) [39]. Another meta-analysis, reporting on studies conducted between 1984 and 2003, found 46% of the reported infections in ticks in the Netherlands, Belgium and northern France to be with B. afzelii, 34% with B. garinii, 33% with B. valaisiana and 19% with B. burgdorferi (s.s.) [31]. In a study in Luxembourg, 33% (n = 52) of the infected ticks were infected with B. afzelii, 30% with B. garinii, 19% with B. valaisiana, 15% with B. burgdorferi (s.s.), 2.5% with B. spielmanii and 0.6% with B. lusitaniae [32]. In a study in Valais, Switzerland, the percentage of Borrelia-positive nymphs infected with B. afzelii was 40%, followed by B. garinii (22%), B. valaisiana (12%) and B. burgdorferi (s.s.) (6%) [3]. Of our 12 locations, only Vaals shows a similarly diverse genospecies composition, which, given that Vaals is the most continentally located of our study sites in the Netherlands and possibly more similar to Luxemburg and Switzerland than the other 11 study locations, may not be surprising. A study in northern Belgium (a region bordering the Netherlands) reported a similar dominance of B. afzelii compared to the other genospecies [35]. In our study, B. afzelii was shown to be the most prevalent genospecies in the questing nymphs in the Netherlands, with higher percentages than have been reported previously for this region in meta-analyses [31, 39], and that B. garinii, B. valaisiana and B. burgdorferi (s.s.) are less prevalent but in some locations make up a substantial part of the infections, while B. spielmanii and B. turdi are only rarely detected in questing nymphs. The genospecies could not be determined for a substantial proportion of the infected nymphs, possibly due to the low Borrelia load in the sample or of coinfection by several Borrelia genospecies. While it cannot be excluded that some genospecies may be slightly harder to detect (which would have created a bias), we assume that the analysis of 60% of the infections provided us with a reasonably reliable estimate of the true genospecies distribution. Given that the genospecies composition is likely to be a result of the local composition of the host animals, we recommend that in future studies, data on host densities should be collected.

Conclusions

Our analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) infection data from a longitudinal study with monthly collections of ticks in 12 locations throughout the Netherlands revealed that: (i) prevalence of infection in nymphs shows a seasonal pattern, with increasing prevalence values between March and August and a decrease afterwards; (ii) the mean prevalence of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) infections in nymphs decreased slightly between 2009 and 2016, whereas the mean density of infected nymphs did not change, as the decrease in prevalence was counteracted by an increase in the density of nymphs; (iii) variation in the density of infected nymphs was mostly caused by variation in the density of nymphs, rather than in the infection prevalence; (iv) Borrelia afzelii was the most commonly observed genospecies, with 75% of the infected nymphs being infected with this genospecies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arthur DR. British ticks. London: Butterworths; 1963.

Brooks ME, Kristensen K, Benthem KJ van, Magnusson A, Berg CW, Nielsen A, et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 2017;9(2):378–400. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2017-066.

Burri C, Cadenas FM, Douet V, Moret J, Gern L. Ixodes ricinus density and infection prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu Lato along a north-facing altitudinal gradient in the Rhône Valley (Switzerland). Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:50–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0569.

Chvostáč M, Špitalská E, Václav R, Vaculová T, Minichová L, Derdáková M. 2018. Seasonal patterns in the prevalence and diversity of tick-borne Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Rickettsia spp. in an urban temperate forest in south western Slovakia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050994

Coipan EC, Fonville M, Tijsse-Klasen E, van der Giessen JWB, Takken W, Sprong H, et al. Geodemographic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato using the 5S–23S rDNA spacer region. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;17:216–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2013.04.009.

Coipan EC, Jahfari S, Fonville M, Maassen C, van der Giessen J, Takken W, et al . Spatiotemporal dynamics of emerging pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2013.00036.

Coipan EC, Jahfari S, Fonville M, Oei GA, Spanjaard L, Takumi K, et al.. Imbalanced presence of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. multilocus sequence types in clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;42:66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2016.04.019.

Diuk-Wasser MA, Hoen AG, Cislo P, Brinkerhoff R, Hamer SA, Rowland M, et al. Human risk of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent, in eastern United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:320–7. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0395.

Egyed L, Élő P, Sréter-Lancz Z, Széll Z, Balogh Z, Sréter T. Seasonal activity and tick-borne pathogen infection rates of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Hungary. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2012;3:90–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.01.002.

Eisen RJ, Eisen L, Girard YA, Fedorova N, Mun J, Slikas B, et al. A spatially-explicit model of acarological risk of exposure to Borrelia burgdorferi-infected Ixodes pacificus nymphs in northwestern California based on woodland type, temperature, and water vapor. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2010;1:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2009.12.002.

Fingerle V, Bergmeister H, Liegl G, Vanek E, Wilske B. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus in Southern Germany. J Spiroch Tick Dis. 1994;1:41–5.

Gassner F. Tick tactics. Interactions between habitat characteristics, hosts and microorganisms in relation to the biology of the sheep tick Ixodes ricinus. PhD thesis. Wageningen: Wageningen University. 2010.

Gassner F, van Vliet AJH, Burgers SLGE, Jacobs F, Verbaarschot P, Hovius EKE, et al. Geographic and temporal variations in population dynamics of Ixodes ricinus and associated Borrelia infections in the Netherlands. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:523–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2010.0026.

Guy EC, Stanek G. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Lyme disease by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:610–1. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.44.7.610.

Hartemink N, van Vliet A, Sprong H, Jacobs F, Garcia-Martí I, Zurita-Milla R, et al. Temporal-spatial variation in questing tick activity in the Netherlands: the effect of climatic and habitat factors. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019;9(7):494–505. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2018.2369

Heylen D, Tijsse E, Fonville M, Matthysen E, Sprong H. Transmission dynamics of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in a bird tick community. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:663–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12059.

Hillyard P. Ticks of north-west Europe: keys and notes for identification of the species. Synopses of the British fauna. Shrewsbury: Field Studies Council; 1996.

Hofhuis A, Bennema S, Harms M, van Vliet AJH, Takken W, van den Wijngaard CC, et al. Decrease in tick bite consultations and stabilization of early Lyme borreliosis in the Netherlands in 2014 after 15 years of continuous increase. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:425. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3105-y.

Hofhuis A, Harms M, van den Wijngaard C, Sprong H, van Pelt W. Continuing increase of tick bites and Lyme disease between 1994 and 2009. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2015;6:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.09.006.

Kesteman T, Rossi C, Bastien P, Brouillard J, Avesani V, Olive N, et al. Prevalence and genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ticks in Belgium. Acta Clin Belg. 2010;65:319–22.

Lambin EF, Tran A, Vanwambeke SO, Linard C, Soti V. Pathogenic landscapes: interactions between land, people, disease vectors, and their animal hosts. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:54.

Lenth R. emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.4.6. 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans.

Lin Y-P, Diuk-Wasser MA, Stevenson B, Kraiczy P. Complement evasion contributes to Lyme Borreliae–host associations. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:634–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.04.011.

Mather TN, Nicholson MC, Donnelly EF, Matyas BT. Entomologic index for human risk of Lyme disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:1066–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008879.

Mysterud A, Easterday W, Qviller L, Viljugrein H, Ytrehus B. Spatial and seasonal variation in the prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in Norway. Parasites Vectors. 2013;6:187. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-187.

Okeyo M, Hepner S, Rollins RE, Hartberger C, Straubinger RK, Marosevic D, et al. Longitudinal study of prevalence and spatio-temporal distribution of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks from three defined habitats in Latvia, 1999–2010. Environ Microbiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15100.

Pepin KM, Eisen RJ, Mead PS, Piesman J, Fish D, Hoen AG, et al. Geographic variation in the relationship between human Lyme disease incidence and density of infected host-seeking Ixodes scapularis nymphs in the eastern United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:1062–71. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0630.

Pérez D, Kneubühler Y, Rais O, Gern L. Seasonality of Ixodes ricinus ticks on vegetation and on rodents and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies diversity in two Lyme Borreliosis-endemic areas in Switzerland. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:633–44. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2011.0763.

Pichon B, Mousson L, Figureau C, Rodhain F, Perez-Eid C. Density of deer in relation to the prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi s.1. in Ixodes ricinus nymphs in Rambouillet forest. France Exp Appl Acarol. 1999;23:267–75. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006023115617.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016.

Rauter C, Hartung T. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato Genospecies in Ixodes ricinus Ticks in Europe: a Metaanalysis. Appl Env Microbiol. 2005;71:7203–16.

Reye AL, Hübschen JM, Sausy A, Muller CP. Prevalence and seasonality of tick-borne pathogens in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks from Luxembourg. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2923–31. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03061-09.

Rosef O, Paulauskas A, Radzijevskaja J. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in relation to the density of wild cervids. Acta Vet Scand. 2009;51:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-51-47.

Ruyts SC, Landuyt D, Ampoorter E, Heylen D, Ehrmann S, Coipan EC, et al. Low probability of a dilution effect for Lyme borreliosis in Belgian forests. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2018;9:1143–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.04.016.

Ruyts SC, Tack W, Ampoorter E, Coipan EC, Matthysen E, Heylen D, et al. Year-to-year variation in the density of Ixodes ricinus ticks and the prevalence of the rodent-associated human pathogens Borrelia afzelii and B. miyamotoi in different forest types. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2018;9:141–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.08.008.

Sormunen JJ, Klemola T, Vesterinen EJ, Vuorinen I, Hytönen J, Hänninen J, et al. Assessing the abundance, seasonal questing activity, and Borrelia and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) prevalence of Ixodes ricinus ticks in a Lyme borreliosis endemic area in Southwest Finland. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:208–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.10.011.

Sprong H, Hofhuis A, Gassner F, Takken W, Jacobs F, van Vliet AJ, et al. Circumstantial evidence for an increase in the total number and activity of Borrelia-infected Ixodes ricinus in the Netherlands. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5:294. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-294.

Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 2012;379:461–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7.

Strnad M, Hönig V, Růžek D, Grubhoffer L, Rego ROM. Europe-wide meta-analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e00609–17. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00609-17.

Takken W, van Vliet AJH, Verhulst NO, Jacobs FHH, Gassner F, Hartemink N, et al. Acarological risk of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infections across space and time in The Netherlands. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:99–107. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2015.1933.

Tälleklint L, Jaenson TGT. Seasonal variations in density of questing Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs and prevalence of infection with B. burgdorferi s.l. in south central Sweden. J Med Entomol. 1996;33:592–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/33.4.592.

Tekenradar. 2020. https://www.tekenradar.nl/ziekte-van-lyme/lyme-in-nederland. Accessed 23 Sept 2020.

Wielinga PR, Gaasenbeek C, Fonville M, de Boer A, de Vries A, Dimmers W, et al. Longitudinal analysis of tick densities and Borrelia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia Infections of Ixodes ricinus ticks in different habitat areas in The Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7594–601. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01851-06.

Zeimes CB, Olsson GE, Hjertqvist M, Vanwambeke SO. Shaping zoonosis risk: landscape ecology vs. landscape attractiveness for people, the case of tick-borne encephalitis in Sweden. Parasites Vectors. 2014;7:370. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-370.

Acknowledgements

The authors are highly appreciative of the monthly tick collections done by the group of volunteers. We thank the managers of several nature reserves for permission to collect ticks in often closed areas, which has greatly facilitated the work presented.

Funding

This study was funded by Wageningen University and Research and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WT, HS and AvV conceived the study; MF, FG and FJ were involved in the data collection and/or the laboratory analyses; NH, GG, HS, WT and AvV were involved in designing the analysis; NH and GG carried out the statistical analysis; NH and HS wrote the first draft; all authors were involved in revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

See Table 2.

Appendix B

See Table 3.

Appendix C

See Table 4.

Appendix D

See Fig. 4.

Appendix E

See Table 5.

Appendix F

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hartemink, N., van Vliet, A.J.H., Gort, G. et al. Seasonal patterns and spatial variation of Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) infections in Ixodes ricinus in the Netherlands. Parasites Vectors 14, 121 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04607-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04607-7