Abstract

Background

Transmission from the vertebrate host to the arthropod vector is a critical step in the life-cycle of any vector-borne pathogen. How the probability of host-to-vector transmission changes over the duration of the infection is an important predictor of pathogen fitness. The Lyme disease pathogen Borrelia afzelii is transmitted by Ixodes ricinus ticks and establishes a chronic infection inside rodent reservoir hosts. The present study compares the temporal pattern of host-to-tick transmission between two strains of B. afzelii.

Methods

Laboratory mice were experimentally infected via tick bite with one of two strains of B. afzelii: A3 and A10. Mice were repeatedly infested with pathogen-free larval Ixodes ricinus ticks over a period of 4 months. Engorged larval ticks moulted into nymphal ticks that were tested for infection with B. afzelii using qPCR. The proportion of infected nymphs was used to characterize the pattern of host-to-tick transmission over time.

Results

Both strains of B. afzelii followed a similar pattern of host-to-tick transmission. Transmission decreased from the acute to the chronic phase of the infection by 16.1 and 29.3% for strains A3 and A10, respectively. Comparison between strains found no evidence of a trade-off in transmission between the acute and chronic phase of infection. Strain A10 had higher lifetime fitness and established a consistently higher spirochete load in nymphal ticks than strain A3.

Conclusion

Quantifying the relationship between host-to-vector transmission and the age of infection in the host is critical for estimating the lifetime fitness of vector-borne pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Many vector-borne pathogens establish long-lived chronic infections in their vertebrate reservoir hosts [1–7]. This life-history strategy enhances pathogen fitness because it facilitates transmission to feeding arthropod vectors over a longer period of time. Tick-borne spirochete bacteria that belong to the Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) (s.l.) species complex cause Lyme borreliosis (LB) in humans [7–9]. These tick-borne pathogens establish chronic infections in competent vertebrate reservoir hosts, such as rodents [10–14]. Experimental infection studies with different species of rodents have shown that B. burgdorferi (s.l.) pathogens can have high host-to-tick transmission to feeding larval ticks over a period of months and even years [10–13]. Theoretical models have shown that the reproductive number (R0) of tick-borne pathogens is highly sensitive to the duration of the infectious period and the probability of host-to-tick transmission [15–18].

Host-to-tick transmission success can vary dramatically over the course of the infection. In the first week post-infection (PI), the Borrelia pathogen replicates in the host skin at the site of the tick bite before disseminating to multiple organs (~10 days PI) [19, 20]. During this time (~7 days PI), uninfected ticks feeding in close proximity to an infected tick can acquire the spirochete infection via non-systemic or co-feeding transmission [21–26]. Once the Borrelia pathogen has established a widespread, multi-organ infection, host-to-tick transmission can occur from the skin anywhere on the vertebrate body and is therefore referred to as systemic transmission [23, 25]. Systemic transmission reaches a maximum (80–100%) between 10 and 40 days depending on the Borrelia species and rodent host [10, 12, 27–30]. At the same time, the host develops an IgG antibody response against Borrelia (15–30 days PI) [20]. These antibodies reduce the spirochete load in the host tissues [31–34], which reduces the efficacy of systemic transmission [35–37]. During the later chronic phase, the Borrelia pathogen employs a variety of strategies to evade the immune system and persist in the vertebrate host [38–40].

Kurtenbach et al. [7] pointed out that many tick-borne pathogens have a ‘boom-and-bust’ life history strategy, where host-to-tick transmission is high during the early acute phase of the infection and lower during the later chronic phase of the infection. A number of studies on Borrelia pathogens have shown that host-to-tick transmission peaks during the first four weeks of infection [10, 12, 27], followed by lower transmission after this period, but this is not always the case [11, 28, 30]. Haven et al. [41] pointed out that the relationship between host-to-tick transmission and the age of infection is a critical driver of the epidemiology of LB. They suggested that Borrelia pathogens could be divided into inhost persistent strains or rapidly cleared strains [41]. For example, B. burgdorferi (sensu stricto) (s.s.) BL206 is an inhost persistent strain because mouse-to-tick transmission increased from 58.3 to 83.3% from day 10 to day 42 [28]. In contrast, strain B348 is a rapidly cleared strain because transmission decreased from 83.3 to 4.1% over the same time period [28]. A number of studies on the North American LB system of B. burgdorferi (s.s.) in I. scapularis ticks have compared the temporal pattern of host-to-tick transmission between strains [27, 28, 30]. In contrast, no such studies have been performed on European LB pathogens.

Borrelia afzelii is the most common cause of LB in Europe. This tick-borne pathogen is transmitted by the tick Ixodes ricinus and is specialized on rodent reservoir hosts [42]. We have previously compared host-to-tick transmission between two isolates of B. afzelii: E61 and NE4049 [25, 26, 35] during the acute phase of the infection (defined here as 1–35 days PI). These studies found that isolate NE4049 had higher co-feeding transmission (day 2 PI) and systemic transmission (day 34 PI) than isolate E61. However, these studies did not investigate host-to-tick transmission during the chronic phase of the infection (defined here as > 35 days PI). Given the potential for life history trade-offs between the acute and chronic phases of the infection, the purpose of the present study was to test whether isolate NE4049 would maintain its transmission advantage relative to isolate E61 during the chronic phase of the infection. We predicted that isolate E61 would have higher transmission during the chronic phase of the infection than isolate NE4049. This is the first study to compare the temporal pattern of host-to-tick transmission between strains of B. afzelii.

Methods

Acute phase versus chronic phase

In the present study, the acute and chronic phase are defined as ≤ 35 days and > 35 days post-infection (PI). The acute phase contains both co-feeding transmission (2 days PI) and systemic transmission (34 days PI) whereas the chronic phase only has systemic transmission (66, 94, 128 days PI). Our 35-day cut-off between the acute and chronic phase is similar to the 30-day cut-off used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to distinguish between early and later signs and symptoms of LB in humans.

Strains of B. afzelii

Borrelia afzelii isolates E61 and NE4049 were used in this study. These isolates have ID numbers 1888 and 1887 in the Borrelia multilocus sequence type (MLST) database, respectively. E61 was originally isolated from a human patient in Austria whereas NE4049 was isolated from an I. ricinus tick in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Isolate E61 has sequence type (ST) ST75 and ospC major group (oMG) A3 whereas isolate NE4049 has ST679 and oMG A10. For simplicity and as we have done elsewhere, these two isolates will hereafter be referred to as B. afzelii ospC strains A3 and A10 [25, 26, 35]. We have previously characterized the co-feeding and systemic transmission phenotypes of these two ospC strains over the acute phase of the infection [25, 26, 35].

Experimental infection of mice with B. afzelii via tick bite

We experimentally infected female Mus musculus Balb/cByJ mice with either B. afzelii ospC strain A3 or strain A10 via nymphal tick bite (total sample size was 41 mice). The details of this infection experiment have been described elsewhere [26, 35]. Briefly, mice were immunized with PBS (control mice) or with one of two recombinant OspC (rOspC) proteins: A3 or A10. All mice were subsequently challenged via tick bite with one of two strains of B. afzelii: A3 or A10. All 16 mice in the homologous group (where the ospC gene of the challenge strain matched the rOspC immunogen) were protected from infectious challenge. In contrast, 13 of the 15 mice in the heterologous group (where the ospC gene of the challenge strain did not match the rOspC immunogen) and the 10 control mice developed a systemic infection following the nymphal challenge. The 18 uninfected mice were excluded from the present study because host-to-tick transmission for these individuals is obviously zero. Of the 23 mice that developed a systemic infection, 10 were infected with strain A3 and 13 were infected with strain A10.

Measure co-feeding and systemic transmission

To measure co-feeding and systemic transmission, mice were infested with larval I. ricinus ticks from our pathogen-free, laboratory colony on five separate occasions at 2, 34, 66, 94 and 128 days after the nymphal challenge. Co-feeding transmission refers to the larval infestation on day 2 PI whereas systemic transmission refers to days 34, 66, 94 and 128 PI. For the first infestation, the co-feeding larvae were placed in a plastic capsule (15 mm in diameter) that was glued to the back of the mouse and that contained the B. afzelii-infected challenge nymphs [26]. For each of the remaining four infestations, 50 to 100 larvae were placed on the head of each mouse. Infested mice were placed in individual cages that facilitated the collection of blood-engorged larval ticks. Blood-engorged larvae were placed in individual tubes and were allowed to moult into nymphs [26, 35]. The nymphs were frozen at -20 °C at 4 weeks after moulting into the nymphal stage. For the first infestation and for all subsequent infestations, a maximum of 20 and 10 nymphs were frozen, respectively.

DNA extraction of nymphal ticks and qPCR to determine B. afzelii infection

A total of 1,174 nymphal ticks were processed during the experiment. Total DNA was extracted using a TissueLyser II and DNeasy 96 Blood & Tissue kit well plates (Qiagen, Basel, Switzerland). The DNA extraction protocol was described in a previous study [35]. A quantitative PCR amplifying a fragment of the flagellin gene [43] was used to detect and quantify Borrelia DNA. The qPCR protocol was described in a previous study [35].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done in R version 3.1.0. [44].

Effects of the age of infection and strain on the B. afzelii infection status of nymphal ticks

Nymphal ticks were considered infected if at least two of the three runs of the qPCR assay tested positive for B. afzelii, as described in a previous study [35]. A generalized linear mixed effects (GLME) model with binomial errors was used to model the B. afzelii infection status of each nymphal tick as a function of two fixed factors: the age of the infection (2, 34, 66, 94 and 128 days), strain (A3 and A10), and their interaction. Mouse identity was included as a random factor.

Effects of the age of infection and strain on the spirochete load of infected nymphal ticks

The spirochete load of each nymphal tick was calculated as the geometric mean of the three replicate runs (negative runs were excluded), as described in a previous study [35]. For the subset of infected nymphs (i.e. uninfected nymphs were excluded), a linear mixed effects (LME) model with normal errors was used to model the log10-transformed spirochete load as a function of the age of the infection, strain, and their interaction. Mouse identity was included as a random factor.

Results

Effects of the age of infection and strain on the B. afzelii infection status of nymphal ticks

Strain A10 had higher transmission than strain A3 at all time points except the last one (Fig. 1). Over the duration of systemic transmission (days 34, 66, 94 and 128), the proportions of infected nymphs produced by strains A10 and A3 were 71.0% (358/504) and 66.1% (248/375), respectively. Systemic transmission of B. afzelii was highest at the acute phase of the infection (day 34) and then decreased but remained stable over the chronic phase (days 66, 94 and 128; Fig. 1). There was a significant interaction between strain and the age of the infection on transmission (GLME: Δ χ 2 = 37.326, df = 4, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). We therefore analysed the effect of the age of infection on the probability of transmission separately for each strain (see below). After removing the interaction from the model, the main effects of strain (GLME: Δ χ 2 = 9.833, df = 1, P = 0.002) and the age of infection (GLME: Δ χ 2 = 128.010, df = 4, P <0.001) remained highly significant.

The transmission of B. afzelii to I. ricinus ticks is shown as a function of the age of infection inside the mouse (2, 34, 66, 94 and 128 days) for each of the two strains, A3 and A10. Transmission data were based on 1,174 I. ricinus nymphs that were sampled from 23 mice at all five time points. Shown are the means and the 95% confidence intervals

For strain A3, the effect of the age of infection was significant (GLME: Δ χ 2 = 104.72, df = 4, P < 0.001). Systemic transmission peaked during the acute phase (day 34: 75.0% = 75/100) and was 16.1% lower during the chronic phase (days 66, 94 and 128 combined: 62.9% = 173/275), and this difference was significant (Proportion test: χ 2 = 4.262, df = 1, P = 0.039). Co-feeding transmission of strain A3 on day 2 was significantly lower than systemic transmission over all subsequent days (P < 0.001). For strain A10, the effect of the age of infection was significant (GLME: Δ χ 2 = 61.524, df = 4, P < 0.001). Systemic transmission peaked during the acute phase (day 34: 90.8% = 118/130) and was 29.3% lower during the chronic phase (days 66, 94, and 128 combined: 64.2% = 240/374) and this difference was significant (Proportion test: χ 2 = 31.887, df = 1, P < 0.001). Co-feeding transmission of strain A10 on day 2 was significantly lower than systemic transmission over all subsequent days (P < 0.001).

Effects of the age of infection and strain on the spirochete load of infected nymphal ticks

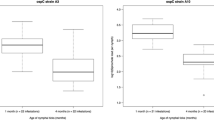

The nymphal spirochete load of strain A10 (~20,000 spirochetes/nymph; Table 1) was consistently higher than that of strain A3 (~10,000 spirochetes/nymph; Table 1, Fig. 2). The interaction between strain and the age of infection on the log10-transformed nymphal spirochete load was not significant (LME: Δ χ 2 = 3.534, df = 4, P = 0.473). In the main effects model, the effects of strain (LME: Δ χ 2 = 10.591, df = 1, P = 0.001) and age (LME: Δ χ 2 = 37.085, df = 4, P < 0.001) were significant. The spirochete load of the nymphs infected via co-feeding transmission on day 2 was significantly lower than that of the nymphs infected via systemic transmission on all subsequent days (P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The mean spirochete load was similar between the days where nymphs were infected via systemic transmission (Fig. 2).

The log10-transformed B. afzelii spirochete load of the subset of infected I. ricinus nymphal ticks is shown as a function of the age of infection (2, 34, 66, 94 and 128 days) for strain A3 (a) and strain A10 (b). Spirochete load data were based on 718 I. ricinus nymphs infected with B. afzellii that were sampled from 23 mice at all five time points. Each data point represents the average nymphal spirochete load for one mouse. Shown are the medians (black line), the 25th and 75th percentiles (edges of the box), the minimum and maximum values (whiskers), and the outliers (circles)

Discussion

The results of our study were consistent with the boom-and-bust model of host-to-tick transmission proposed by Kurtenbach et al. [7]. For strains A3 and A10, host-to-tick transmission was highest (75.0 and 90.8%, respectively; Table 1) at the end of the acute phase of the infection (day 34 PI), followed by a plateau of lower (but still high) transmission (62.9 and 64.2%, respectively; Table 1) over the chronic phase of the infection (days 66, 94 and 128 days PI). The reduction in the efficiency of systemic transmission between the acute and chronic phase of the infection was 16.1 and 29.3% for strains A3 and A10, respectively. Our results are similar to an earlier experimental infection study of B. afzelii in the wood mouse, Apodemus sylvaticus [12]. In that study, host-to-tick transmission was very high (100%) during the acute phase (days 18 to 22 PI) followed by a plateau of lower transmission (30–50%) during the chronic phase (weeks 9, 15, 21, 27 and 33 PI) [12]. Others and we have shown that host-to-tick transmission depends on the density of Borrelia spirochetes in the host tissues [35–37]. Previous work has shown that Borrelia-specific antibodies of the host immune system play a key role in controlling the spirochete load in the host tissues [31–34]. Thus antibodies are the most likely explanation for the observed decrease in host-to-tick transmission from the acute to the chronic phase of the infection [45–47].

Haven et al. [41] suggested that Borrelia pathogens could be divided into inhost persistent strains or rapidly cleared strains [41]. In the present study, B. afzelii strains A3 and A10 established a chronic infection and are therefore both inhost persistent strains. Strain A10 had consistently higher host-to-tick transmission than strain A3 (except for the last time point) and the temporal pattern of transmission was similar between the two strains (Fig. 1). Thus, comparison of the two strains found no evidence of a transmission trade-off between early and late infection as found in B. burgdorferi (s.s.) by Haven et al. [41]. Likewise, a previous study comparing six strains of B. afzelii in laboratory mice found no evidence of a trade-off between co-feeding transmission and systemic transmission during the acute phase of the infection [25]. In contrast, a study on two North American strains of B. burgdorferi (s.s.) in the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus, found large differences in the temporal pattern of host-to-tick transmission [27, 28]. For the inhost persistent strain BL206, mouse-to-tick transmission increased from 58.3 to 83.3% from day 10 PI to day 42 PI, whereas for the rapidly cleared strain B348, transmission decreased from 83.3 to 4.1% over the same time period [28]. In summary, our study showed that strain A10 has a higher lifetime transmission success than strain A3.

The relationship between host-to-tick transmission and the age of infection is a critical driver of the epidemiology of LB [41]. The relationship between host-to-tick transmission and the age of infection in the reservoir host is also important for the development of theoretical models. Recently developed next-generation population matrix models typically assume that host-to-tick transmission is constant and high over the duration of the infection [15–17]. We recently used these next-generation matrix methods to estimate the R0 value for six different ospC strains of B. afzelii [25]. The matrices were parameterized with transmission data that had been collected over the acute phase of the infection [25]. The present study shows that these theoretical models should consider incorporating the decrease in transmission efficiency between the acute and the chronic phase of the infection.

The two strains differed in their spirochete load in the nymphal ticks. We had previously shown that the mean spirochete load in nymphs infected as larvae via systemic transmission during the acute phase of the infection was two-fold higher for strain A10 than for strain A3 [35]. In the present study, we show that this two-fold difference in nymphal spirochete load between strains A10 and A3 is maintained during the chronic phase of the infection (Table 1). We have recently shown in B. afzelii that ospC strains that maintain a high spirochete load in the nymphal tick are more common in our local population of I. ricinus ticks [48]. This observation suggests that the spirochete load is an important life-history trait for Borrelia pathogens. Spirochetes have to persist in the flat nymph for a long period of time (~8 months) until the nymph takes its first (and only) blood meal [29, 49]. The spirochete population size inside the tick midgut is likely to be important for maintaining a persistent infection inside the nymphal tick [50–52]. In addition, during the nymphal blood meal, only a small fraction of spirochetes complete the migration from the tick midgut to the tick salivary glands [53–55]. A recent study using genetically tagged strains of B. burgdorferi (s.s.) found that strains with higher spirochete loads in the nymph have a higher probability of tick-to-host transmission [37]. The ability of strain A10 to establish a high spirochete load inside the nymph may explain why this strain is so common in nature [48].

We recently characterized the community of B. afzelii ospC strains in a local population of I. ricinus nymphs over a period of 11 years [56]. For the subset of nymphs that were infected with B. afzelii, strains carrying ospC major group (oMG) A10 (54.4% = 105/193) were almost 12 times more common than strains carrying oMG A3 (4.7% = 9/193) [56]. An experimental infection study found that strain A10 is highly efficient at the three canonical fitness components of any tick-borne pathogen: tick-to-host transmission, host-to-tick transmission (during the acute phase of the infection), and co-feeding transmission [25]. In that study, isolate NE4049 (corresponding to strain A10 in the present study) had the highest R0 value among the nine tested isolates of B. afzelii [25]. Thus A10 is the most common B. afzelii ospC strain in our local population of ticks because it has high fitness (high R0 value) [25] and because it maintains a high spirochete load inside the nymphal ticks (which translates into high persistence and high tick-to-host transmission) [48]. Recent studies have shown that oMG A10 is common in other parts of Switzerland [57] and Sweden [58]. Surprisingly, genetic screening of human isolates has never recovered B. afzelii oMG A10 from a human patient [59–61]. Future studies should screen human isolates of B. afzelii to test whether strains carrying oMG A10 are infectious to humans.

If strain A10 has higher lifetime transmission success than strain A3, what allows strain A3 to persist in nature? One possible explanation is the hypothesis of multiple niche polymorphism (MNP), which suggests that these strains are adapted to different vertebrate reservoir hosts [38, 62–64]. The MNP hypothesis was proposed for B. burgdorferi (s.s.) in North America where different ospC strains appear to be associated with different small mammal hosts [62–64]. In Europe, there are not many studies that have investigated the MNP hypothesis, but one study in France found that an invasive species of chipmunk and the native bank vole carried different strains of B. afzelii [65]. In summary, strain A3 could persist in nature if it is adapted to a different vertebrate host than strain A10. Another explanation for the persistence of strain A3 is the competition hypothesis, which suggests that performance in single strain infections is not necessarily predictive of performance in mixed or multiple strain infections. For example, experimental infection studies with rodent malaria and African sleeping sickness have shown that avirulent strains can suppress the density of fast-growing virulent strains [66, 67]. Mixed or multiple strain infections of Borrelia pathogens are common in both the vertebrate host [57, 58, 62, 63, 68–70] and the tick vector [48, 56, 57, 62, 71–73]. The mean spirochete load per Borrelia strain decreases as strain richness increases in both the vertebrate host and the tick vector, suggesting the presence of competition between Borrelia strains [48, 70, 73]. To date, there are only two experimental studies that have investigated mixed Borrelia strain infections in the rodent host, but both of these studies were inconclusive with respect to whether co-infection influenced host-to-tick transmission [28, 30]. Thus strain A3 may persist if it is a better competitor than strain A10 in mixed infections in either the vertebrate host or the tick. Future experiments should compare host-to-tick transmission success between mice infected with single strains and mice co-infected with multiple strains.

Conclusions

The pattern of host-to-tick transmission of B. afzelii over the acute and chronic phase of the infection was consistent with the boom-and-bust model of Kurtenbach et al. [7]. The efficiency of systemic transmission decreased between the acute and chronic phase of the infection by 16.1 and 29.3% for strains A3 and A10, respectively. In contrast to studies on North American strains of B. burgdorferi (s.s.), the present study found no strains with the rapidly cleared phenotype. A3 and A10 were both inhost persistent strains with high host-to-tick transmission over the duration of the infection. Strain A10 had slightly higher host-to-tick transmission and established a consistently higher spirochete load in the nymphal tick than strain A3. Nymphal spirochete load is an important life-history trait for Borrelia and may explain why strain A10 is so common in nature.

Abbreviations

- GLME:

-

Generalized linear mixed effects

- LB:

-

Lyme borreliosis

- LME:

-

Linear mixed effects

- OspC:

-

Outer surface protein C

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered solution

- R0 :

-

Reproductive number

References

Carod-Artal FJ. American trypanosomiasis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;114:103–23.

Maguina C, Guerra H, Ventosilla P. Bartonellosis. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(3):271–80.

Malvy D, Chappuis F. Sleeping sickness. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(7):986–95.

Herwaldt BL. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–9.

Asghar M, Westerdahl H, Zehtindjiev P, Ilieva M, Hasselquist D, Bensch S. Primary peak and chronic malaria infection levels are correlated in experimentally infected great reed warblers. Parasitology. 2012;139(10):1246–52.

Snounou G, Jarra W, Preiser PR. Malaria multigene families: the price of chronicity. Parasitol Today. 2000;16(1):28–30.

Kurtenbach K, Hanincova K, Tsao JI, Margos G, Fish D, Ogden NH. Fundamental processes in the evolutionary ecology of Lyme borreliosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:660–9.

Tsao J. Reviewing molecular adaptations of Lyme borreliosis spirochetes in the context of reproductive fitness in natural transmission cycles. Vet Res (Paris). 2009;40:2.

Schotthoefer AM, Frost HM. Ecology and epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(4):723–43.

Donahue JG, Piesman J, Spielman A. Reservoir competence of white-footed mice for Lyme disease spirochetes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;36:92–6.

Gern L, Siegenthaler M, Hu CM, Leuba-Garcia S, Humair PF, Moret J. Borrelia burgdorferi in rodents (Apodemus flavicollis and A. Sylvaticus): duration and enhancement of infectivity for Ixodes Ricinus ticks. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:75–80.

Richter D, Klug B, Spielman A, Matuschka FR. Adaptation of diverse Lyme disease spirochetes in a natural rodent reservoir host. Infect Immun. 2004;72(4):2442–4.

Humair PF, Rais O, Gern L. Transmission of Borrelia afzelii from Apodemus mice and Clethrionomys voles to Ixodes ricinus ticks: differential transmission pattern and overwintering maintenance. Parasitology. 1999;118:33–42.

Barthold SW, Desouza MS, Janotka JL, Smith AL, Persing DH. Chronic Lyme borreliosis in the laboratory mouse. Am J Pathol. 1993;143(3):959–72.

Harrison A, Bennett N. The importance of the aggregation of ticks on small mammal hosts for the establishment and persistence of tick-borne pathogens: an investigation using the R-0 model. Parasitology. 2012;139(12):1605–13.

Harrison A, Montgomery WI, Bown KJ. Investigating the persistence of tick-borne pathogens via the R-0 model. Parasitology. 2011;138(7):896–905.

Hartemink NA, Randolph SE, Davis SA, Heesterbeek JAP. The basic reproduction number for complex disease systems: defining R-0 for tick-borne infections. Am Nat. 2008;171(6):743–54.

Matser A, Hartemink N, Heesterbeek H, Galvani A, Davis S. Elasticity analysis in epidemiology: an application to tick-borne infections. Ecol Lett. 2009;12(12):1298–305.

Shih CM, Spielman A, Pollack RJ, Telford SR. Delayed dissemination of Lyme disease spirochetes from the site of deposition in the skin of mice. J Infect Dis. 1992;166(4):827–31.

Barthold SW, Persing DH, Armstrong AL, Peeples RA. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi dissemination and evolution of disease after intradermal inoculation of mice. Am J Pathol. 1991;139(2):263–73.

Gern L, Rais O. Efficient transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi between cofeeding Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1996;33:189–92.

Randolph SE, Gern L, Nuttall PA. Co-feeding ticks: epidemiological significance for tick-borne pathogen transmission. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:472–9.

Voordouw MJ. Co-feeding transmission in Lyme disease pathogens. Parasitology. 2015;142(2):290–302.

Richter D, Allgower R, Matuschka FR. Co-feeding transmission and its contribution to the perpetuation of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia afzelii. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(12):1421–5.

Tonetti N, Voordouw MJ, Durand J, Monnier S, Gern L. Genetic variation in transmission success of the Lyme borreliosis pathogen Borrelia afzelii. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6(3):334–43.

Jacquet M, Durand J, Rais O, Voordouw MJ. Strain-specific antibodies reduce co-feeding transmission of the Lyme disease pathogen, Borrelia afzelii. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(3):833–45.

Hanincova K, Ogden NH, Diuk-Wasser M, Pappas CJ, Iyer R, Fish D, et al. Fitness variation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strains in mice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(1):153–7.

Derdakova M, Dudioak V, Brei B, Brownstein JS, Schwartz I, Fish D. Interaction and transmission of two Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strains in a tick-rodent maintenance system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(11):6783–8.

Lindsay LR, Barker IK, Surgeoner GA, McEwen SA, Campbell GD. Duration of Borrelia burgdorferi infectivity in white-footed mice for the tick vector Ixodes scapularis under laboratory and field conditions in Ontario. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33(4):766–75.

Devevey G, Dang T, Graves CJ, Murray S, Brisson D. First arrived takes all: inhibitory priority effects dominate competition between co-infecting Borrelia burgdorferi strains. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:61.

Barthold SW, Hodzic E, Tunev S, Feng S. Antibody-mediated disease remission in the mouse model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect Immun. 2006;74(8):4817–25.

Hodzic E, Feng SL, Freet KJ, Barthold SW. Borrelia burgdorferi population dynamics and prototype gene expression during infection of immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71(9):5042–55.

Liang F, Yan J, Mbow ML, Sviat S, Gilmore R, Mamula M, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi changes its surface antigenic expression in response to host immune responses. Infect Immun. 2004;72(10):5759–67.

Liang FT, Brown EL, Wang T, Lozzo RV, Fikrig E. Protective niche for Borrelia burgdorferi to evade humoral immunity. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(3):977–85.

Jacquet M, Durand J, Rais O, Voordouw MJ. Cross-reactive acquired immunity influences transmission success of the Lyme disease pathogen, Borrelia afzelii. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;36:131–40.

Raberg L. Infection intensity and infectivity of the tick-borne pathogen Borrelia afzelii. J Evol Biol. 2012;25:1448–53.

Rego ROM, Bestor A, Stefka J, Rosa PA. Population bottlenecks during the infectious cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e101009.

Brisson D, Drecktrah D, Eggers C, Samuels DS. Genetics of Borrelia burgdorferi. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:515–36.

Palmer GH, Bankhead T, Lukehart SA. ‘Nothing is permanent but change’ - antigenic variation in persistent bacterial pathogens. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11(12):1697–705.

Hovius JWR, van Dam AP, Fikrig E. Tick-host-pathogen interactions in Lyme borreliosis. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23(9):434–8.

Haven J, Magori K, Park A. Ecological and inhost factors promoting distinct parasite life-history strategies in Lyme borreliosis. Epidemics. 2012;4(3):152–7.

van Duijvendijk G, Sprong H, Takken W. Multi-trophic interactions driving the transmission cycle of Borrelia afzelii between Ixodes ricinus and rodents: a review. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:1–11.

Schwaiger M, Peter O, Cassinotti P. Routine diagnosis of Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) infections using a real-time PCR assay. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7(9):461–9.

R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna. Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2009.

Connolly SE, Benach JL. The versatile roles of antibodies in Borrelia infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(5):411–20.

LaRocca TJ, Benach JL. The important and diverse roles of antibodies in the host response to Borrelia infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;319:63–103.

Barthold SW. Specificity of infection-induced immunity among Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species. Infect Immun. 1999;67(1):36–42.

Durand J, Herrmann C, Genné D, Sarr A, Gern L, Voordouw MJ. Multi-strain infections of the Lyme borreliosis pathogen in the tick vector. Appl Environ Microbiol (in press).

Talleklint L, Jaenson TGT. Is the small mammal (Clethrionomys glareolus) or the tick vector (Ixodes ricinus) the primary overwintering reservoir for the Lyme borreliosis spirochete in Sweden. J Wildl Dis. 1995;31(4):537–40.

Fazzino L, Tilly K, Dulebohn DP, Rosa PA. Long term survival of Borrelia burgdorferi lacking hibernation promotion factor homolog in the unfed tick vector. Infect Immun. 2015;83(12):4800–10.

Kung F, Anguita J, Pal U. Borrelia burgdorferi and tick proteins supporting pathogen persistence in the vector. Future Microbiol. 2013;8(1):41–56.

Pappas CJ, Iyer R, Petzke MM, Caimano MJ, Radolf JD, Schwartz I. Borrelia burgdorferi requires glycerol for maximum fitness during the tick phase of the enzootic cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(7):e1002102.

Dunham-Ems SM, Caimano MJ, Pal U, Wolgemuth CW, Eggers CH, Balic A, et al. Live imaging reveals a biphasic mode of dissemination of Borrelia burgdorferi within ticks. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(12):3652–65.

Ohnishi J, Piesman J, de Silva AM. Antigenic and genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi populations transmitted by ticks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(2):670–5.

Piesman J, Schneider BS, Zeidner NS. Use of quantitative PCR to measure density of Borrelia burgdorferi in the midgut and salivary glands of feeding tick vectors. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(11):4145–8.

Durand J, Jacquet M, Paillard L, Rais O, Gern L, Voordouwa MJ. Cross-immunity and community structure of a multiple-strain pathogen in the tick vector. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(22):7740–52.

Pérez D, Kneubühler Y, Rais O, Jouda F, Gern L. Borrelia afzelii ospC genotype diversity in Ixodes ricinus questing ticks and ticks from rodents in two Lyme borreliosis endemic areas: contribution of co-feeding ticks. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2(3):137–42.

Andersson M, Scherman K, Raberg L. Multiple-strain infections of Borrelia afzelii: a role for within-host interactions in the maintenance of antigenic diversity? Am Nat. 2013;181(4):545–54.

Baranton G, Seinost G, Theodore G, Postic D, Dykhuizen D. Distinct levels of genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with different aspects of pathogenicity. Res Microbiol. 2001;152(2):149–56.

Bunikis J, Garpmo U, Tsao J, Berglund J, Fish D, Barbour AG. Sequence typing reveals extensive strain diversity of the Lyme borreliosis agents Borrelia burgdorferi in North America and Borrelia afzelii in Europe. Microbiol-Sgm. 2004;150:1741–55.

Lagal V, Postic D, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Baranton G. Genetic diversity among Borrelia strains determined by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of the ospC gene and its association with invasiveness. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(11):5059–65.

Brisson D, Dykhuizen DE. ospC diversity in Borrelia burgdorferi: different hosts are different niches. Genetics. 2004;168:713–22.

Vuong HB, Canham CD, Fonseca DM, Brisson D, Morin PJ, Smouse PE, et al. Occurrence and transmission efficiencies of Borrelia burgdorferi ospC types in avian and mammalian wildlife. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;27:594–600.

Hanincova K, Kurtenbach K, Diuk-Wasser M, Brei B, Fish D. Epidemic spread of Lyme borreliosis, Northeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(4):604–11.

Jacquot M, Bisseux M, Abrial D, Marsot M, Ferquel E, Chapuis JL, et al. High-throughput sequence typing reveals genetic differentiation and host specialization among populations of the Borrelia burgdorferi species complex that infect rodents. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88581.

Abkallo HM, Tangena J-A, Tang J, Kobayashi N, Inoue M, Zoungrana A, et al. Within-host competition does not select for virulence in malaria parasites; studies with Plasmodium yoelii. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(2):e1004628.

Balmer O, Stearns SC, Schotzau A, Brun R. Intraspecific competition between co-infecting parasite strains enhances host survival in African trypanosomes. Ecology. 2009;90(12):3367–78.

Swanson KI, Norris DE. Presence of multiple variants of Borrelia burgdorferi in the natural reservoir Peromyscus leucopus throughout a transmission season. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8(3):397–405.

Heylen D, Matthysen E, Fonville M, Sprong H. Songbirds as general transmitters but selective amplifiers of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genotypes in Ixodes rinicus ticks. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16(9):2859–68.

Strandh M, Raberg L. Within-host competition between Borrelia afzelii ospC strains in wild hosts as revealed by massively parallel amplicon sequencing. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2015;370:1675.

Wang IN, Dykhuizen DE, Qiu W, Dunn JJ, Bosler EM, Luft BJ. Genetic diversity of ospC in a local population of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Genetics. 1999;151:15–30.

Qiu WG, Dykhuizen DE, Acosta MS, Luft BJ. Geographic uniformity of the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) and its shared history with tick vector (Ixodes scapularis) in the northeastern United States. Genetics. 2002;160(3):833–49.

Walter KS, Carpi G, Evans BR, Caccone A, Diuk-Wasser MA. Vectors as epidemiological sentinels: patterns of within-tick Borrelia burgdorferi diversity. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(7):e1005759.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by an SNSF grant to Maarten Voordouw (FN 31003A_141153).

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Additional file 1.

Authors’ contributions

MJ and MJV conceived and designed the study. MJ conducted the experimental work and the statistical analyses. GM and VF performed the MLST typing of the two B. afzelii isolates. MJ and MJV wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. This study is part of the PhD thesis of MJ.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The commission that is part of the ‘Service de la Consommation et des Affaires Vétérinaires (SCAV)’ of Canton Vaud, Switzerland evaluated and approved the ethics of this study. The Veterinary Service of the Canton of Neuchâtel, Switzerland issued the animal experimentation permit used in this study (NE2/2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Data analysed in the present study. (XLSX 154 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jacquet, M., Margos, G., Fingerle, V. et al. Comparison of the lifetime host-to-tick transmission between two strains of the Lyme disease pathogen Borrelia afzelii . Parasites Vectors 9, 645 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1929-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1929-z