Abstract

Background

The phosphinato complexes of group IIB are of great interest for their potential toward technological applications. A gas phase mechanistic investigation of the chemical vapour deposition of cadmium chalcogenides from the decomposition of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2, as a single source precursor is carried out and reported herein within the framework of density functional theory at the M06/LACVP* level of theory.

Results

The results reveal that the activation barriers and the product stabilities on the singlet potential energy surface (PES) favour CdS decomposition pathways, respectively. However, on the doublet PES, the activation barriers favour CdS while the product stabilities favour CdSe decomposition pathways, respectively. Contrary to the previously reported theoretical result for Cd[(iPr)2PSSe]2, CdSe decomposition pathways were found to be the major pathways on both the singlet and the doublet PESs, respectively.

Conclusion

Exploration of the complex gas phase mechanism and a detailed identification of the reaction intermediates enable us to understand and optimise selective growth process that occur in a chemical vapour deposition.

Structure of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 single-source precursor

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The chemical and coordinating properties of anionic ligands R2PCh −2 with phosphorus, sulphur and selenium donor atoms (Ch = S, Se) are well documented [1–6]. Dithiophosphinates R2PS2 − and diselenophosphinates R2PSe −2 , where R = alkyl or aryl, are known and widely used as single source precursors of remarkable nanomaterials [7–10] and ligands for metal complexes [11–18]. Moreover, thioselenophosphinates represent rare anionic conjugate triads of “S-P-Se” type, possessing of S,Se-ambident reactivity, a type of compounds which is nearly unexplored [19–25].

II–VI nanostructure semiconductors have been of considerable interest in the past decade due to their unique optical and electrical properties, and good candidates for the building blocks of functional Nano devices such as field-effect transistors (FETs), [26, 27] photo detectors (PDs), [28, 29] light-emitting diodes (LEDs), [30] photovoltaic (PV) devices [31, 32] and logic circuits [33, 34]. Semiconductor materials such as CdSe, CdTe, and CdSexTe1−x are the bases of modern electronic devices. CdSe is one of the most promising semiconducting materials with potential applications in solar cells, [35, 36] γ-ray detectors, [37] thin film transistors, [38] etc. Doped semiconductor Nano crystals with transition metals have attracted much attention due to their unique properties [39–41].

Gas-phase chemistry for the chemical vapour deposition (CVD) of metal precursors has been the subjects of theoretical investigations as gas-phase reactions, in particular, are found to play a key role in CVD process which has a number of important industrial and commercial applications. Theoretical data on single-source precursor bearing the thioselenophosphinate groups, [R2PSeS], are lacking in literature. Very recently, we have undertaken a theoretical study on several single source precursors (SSPs) to deposit metal chalcogenides via the gas phase decomposition process [42–46]. Spurred by the success of the use of SSPs and motivated by their potential to reduce the environmental impact of material processing, we have been keenly interested in investigating new routes to prepare SSPs. In addition, ligands binding strength on single-source metal precursor can be employed to tune the decomposition kinetics of the complex. Contrary, multiple-source routes often use highly toxic and/or oxygen or moisture sensitive gases, or very volatile ligands, such as: (CH3)2Cd (Et3)3Ga, H2E (E = S or Se) or EH3 (E = N, P or As).

In continuation of our research into thioselenophosphinato metal complexes, we have investigated the possibility of the gas phase decomposition of single source precursors within Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 complex. To gain insight into the complete reaction features, theoretically we have employed density functional theory technique. The reaction kinetics is also studied, employing standard transition state theory to evaluate the rate constant of the elementary reactions involved.

Computational details

All calculations were carried out with Spartan‘10 v1.1.0 Molecular Modelling program [47] at the DFT M06/LACVP* level in order to maximize the accuracy on the chemically active electrons of the reactions while minimizing computational time. LACVP* basis set uses the Hay–Wadt ECP basis set for cadmium, [48] and the 6-31G* basis set for all other atoms [49] as implemented in Spartan [47]. Zhao and Truhlar [50] recently developed the M06 family of local (M06-L) and hybrid (M06, M06-2X) meta-GGA functionals that show promising performance for the kinetic and thermodynamic calculations without the need to refine the energies by post Hartree–Fock methods. The M06 is reported to show excellent performance for transition metal energetics [50] and is therefore strongly recommended for transition metal chemistry [51].

The starting geometries of the molecular systems were constructed using Spartan’s graphical model builder and minimized interactively using the sybyl force field [52]. The equilibrium geometries of all molecular species were fully optimized without any symmetry constraints. Frequency calculations were carried out for all the stationary points at the corresponding level of theory to characterize the optimized structures as local minima (no imaginary frequency) or as transition states (one imaginary frequency) on the potential energy surfaces. The connecting first-order saddle points, the transition states between the equilibrium geometries, are obtained using a series of constrained geometry optimization in which the breaking bonds were fixed at various lengths and optimized the remaining internal coordinates.

The rate constants were computed using the transition state theory for the selected reaction pathways [53, 54].

where ΔG‡ is the activation free-energy, ΔGo is the Gibbs free energy, and kB and h are the Boltzmann and Planck constants, respectively.

Mechanistic considerations

The reaction pathways for the gas phase decomposition of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 complex were based on the possible routes suggested Akhtar et al. [55] and Opoku et al. [42–46]. Schemes 1, 2, 3, 4 takes into account all these probable theoretically investigated decomposition pathways.

Results and discussion

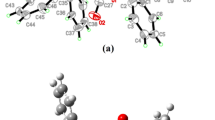

Optimized geometry of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 precursor

Table 1 shows the M06/LACVP* calculated geometries for the Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 and Cd[(iPr)2PSSe]2 precursors. The Cd–Se bond lengths are in the range of 2.99–3.02 Å which are slightly longer than the Cd[(iPr)2PSSe]2 precursor 2.81 Å [42]. The bond angle of Se1–Cd–S1 (79.1°) is more acute than the Se–Cd–Se angle in Cd[(SePiPr2)2N]2 [111.32(6)u] [56]. The average Cd–Se bond lengths, 3.01 Å, as expected are longer than the Cd–S distance, 2.59 Å. The S–Cd–Se angle (79°) is smaller than the S–P–Se angle (119°) due to the large amount of repulsion between the lone pairs of electrons of phosphorus with those of cadmium. The wider Se1–Cd–Se2 bond angle of 159.4° was as a result of the proximity of the non-coordinating Se-donor atoms to the Cd(II) atom.

The geometry around P1 and P2 is a distorted tetrahedral (Se1–P1–S1 and S2–P2–Se2: 118.5 and 118.7). The structure of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 precursor adopts a symmetric and puckered macro cyclic framework, with the two phenyl rings directly attached to phosphorus atoms being parallel to each other. The Se–P–Se bond angles are enlarged from ideal tetrahedral Se1–P1–S1 and S2–P2–Se2: 118.5 and 118.7, respectively, and are considerably slightly larger than those in Cd[(iPr)2PSSe]2 precursor [112.3 and 112.3] [42].

Overall decomposition of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 precursor

The following discussions are aimed at elucidating the detailed mechanistic scenario and thereby providing a molecular level understanding of the complete reaction features associated with Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 precursor. Twenty four reactions have been investigated in total: seven energy minima and seventeen transition states. The relative energies and the optimized geometries of all the species involved in the (C6H5)PSSe–Cd–Se and (C6H5)PSSe–Cd–S decomposition are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2.

Unimolecular decomposition of R1 via pathway 1 is associated with the elimination of phenyl radical leading to the formation of a (C6H5)2PSSe–Cd–SeSP(C6H5) intermediate, INT1/d (Fig. 2). This dissociation pathway passes through a singlet transition state TS1/s with a barrier height of 40.64 kcal/mol and reaction energy of 34.58 above the initial reactant on the doublet potential energy surface. This barrier is significantly lower than the barrier for the formation of the (iPr)2PSSe–Cd–SeSP(iPr) intermediate (∼77 kcal/mol) [42].

A doublet transition state was obtained for the (C6H5)2PSSe–Cd–Se intermediate, INT2/d and was found to be 3.93 kcal/mol lower than the (C6H5)2PSSe–Cd–S intermediate INT3/d. This process is found to be exergonic, producing INT2/d at an energy level of 11.43 kcal/mol below the initial intermediate, INT1/d. A doublet transition state, TS2/d, located for this conversion, is a four-membered cyclic transition state and involves the dissociation of the Cd–S and P–Se bonds. In TS2/d, the Cd–S and P–Se bonds are elongated by 0.35 and 2.18 Å, respectively relative to the initial intermediate, INT1/d. The formation of the (C6H5)2PSSe-Cd-S intermediate, INT3/d via a doublet transition state TS3/d has an activation barrier and a relative free energy of 17.46 and 4.50 kcal/mol, respectively below INT1/d.

Decomposition of INT2/d along pathway 3 proceeds through a phenyl-dissociation transition state (TS4/d) in which the dissociation of the phenyl-radical is 3.85 Å away from the P atom. This process is associated with an activation barrier of +36.87 kcal/mol. The process is found to be exergonic, producing INT4/s at an energy level of 4.57 kcal/mol below the INT2/d. As outlined before [42], another plausible decomposition route occurs by the decomposition of phenyl group from the INT3/d. This pathway leads to the formation of INT5/s (shown in Fig. 3) passing through a doublet transition state, TS5/d accounts for the dissociation of the phenyl radical being 2.93 Å away from the associated P atom. INT5/s is produced at an energy level of 18.42 kcal/mol below the INT3/d. The phenyl-dissociation transition state, TS5/d, possesses an activation barrier of 32.83, ∼4 kcal/mol lower than pathway 3 discussed above.

It was reckoned that the (C6H5)PSSe–Cd–Se INT4/s intermediate produced in Scheme 1 may then decompose in two ways, either through the formation of CdSe or ternary CdSexS1−x. The energetics of such reaction was investigated and it was found that the activation barrier and the reaction energy for the formation of CdSe through a singlet transition state is +73.97 and −29.86 kcal/mol, respectively. The formation of ternary CdSexS1−x has an activation barrier and a reaction energy of +71.43 and −26.83 kcal/mol, respectively. The activation barrier for the formation of the CdS by the dissociation of the Cd–S and Cd–Se bonds from (C6H5)PSSe–Cd–S INT5/s intermediate is +95.15 kcal/mol (Fig. 5). This is much higher than the barrier for the formation of the ternary CdSexS1−x.

As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, the final decomposition pathways that were considered have a higher activation barrier. It is worth noting that the higher energy values of the transition states associated with the final pathways are consistent with the strained, four cantered nature of the calculated transition state structures. The lowest barrier (∼60 kcal/mol) on the potential energy surfaces is ternary CdSexS1−x dissociation pathway. A rate constant of 7.88 × 10−7 s−1, 1.86 × 108 mol L−1 and 1.61 × 10−4 mol L−1 s−1 were estimated for this pathway (Table 2). In terms of energetic, the formation CdSe is the thermodynamically more stable product on the reaction PES (Fig. 2). The rate constant along this pathway is 1.86 × 108 mol L−1 (Table 2). Though Opoku et al. [42] found the CdS-elimination pathway as the most favoured pathway and ternary CdSexS1−x elimination as the most disfavoured one in their calculation using Cd[(iPr)2PSSe]2 analogue, the present study suggest the ternary CdSexS1−x formation pathway as the most favoured pathway followed by CdSe and CdS-elimination pathways among the several possible decomposition pathways discussed above for the gas-phase thermal decomposition of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 precursor.

As outlined before, another plausible decomposition route originating from R1 is Cd–Se and Cd–S elimination (Scheme 3). The fully optimized geometries of all the reactants, intermediates, transition states (TS), and products involved in the Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 decomposition are shown in Fig. 4. Decomposition of R1 proceeds through the dissociation of Cd–Se and Cd–S bonds on one side of the ligand via a singlet transition state to form a (C6H5)2PSSe–Cd intermediate on the doublet PES, which is like the loss of a phenyl radical in Scheme 1. This process is associated with an activation barrier and a reaction energy of 43.48 and 28.41 kcal/mol above the initial reactant, R. The (C6H5)2PSSe–Cd intermediate, INT6/d, formed can enter into three successive reactions.

As shown in Fig. 4, further decomposition of INT6/d may lead to the formation of CdSe (shown in Scheme 3) through Cd–S and P–Se elimination. This passes through the transition state TS11/d and requires a barrier height of 28.68 kcal/mol above the INT6/d; the corresponding reaction energy is 37.80 below the reactant. The Cd–S bond elongates from 2.48 Å in the complex to 2.87 Å in the transition state, and the P–Se bond also elongates from 2.20 Å in the complex to 2.96 Å in the transition state.

Another subsequent elimination may follow from INT6/d and give rise to the formation of CdS with the elimination of Cd–Se and P–S bonds. The Cd–Se and P–S bond distances elongate from 2.50 and 2.10 Å in the complex to 3.11 and 2.92 Å in the transition state. This process requires a barrier height of 21.82 kcal/mol at TS12/d and free energy of −29.11 kcal/mol (Fig. 4). Therefore, the results suggest that the dissociation of CdS is kinetically preferred over the dissociation of CdSe.

A subsequent decomposition via INT6/d, leads to the formation of a ternary CdSexS1−x. This process needs to go over a barrier of 28.07 kcal/mol (relative to INT6/d) via a doublet transition state TS13/d. The reaction is calculated to be exergonic by 37.77 kcal/mol (relative to INT6/d). The P–Se and P–S bonds elongate from 2.20 and 2.10 Å in the complex to 3.10 and 2.95 Å in the transition state.

Among the three possible heterolytic dissociations pathway, the CdSe dissociation pathway is slightly the most stable species on the reaction PES, with a free energy of about 0.03 kcal/mol lower than the CdS. The results suggest that, the heterolytic pathway of CdSe through the [(C6H5)2PSSe]− anion is highly competitive with the CdS pathway. Moreover, in terms of kinetic, the CdS dissociation is the most favourable pathway than the CdSe and ternary CdSexS1−x pathways and a rate constant of 3.17 × 10−1 s−1 was estimated (Table 2).

The (C6H5)2PSSe–Cd intermediate, INT6/d thus formed, is widely believed to be an important precursor for the growth of the cadmium chalcogenides. Understanding the decomposition of INT6/d is therefore crucial in order to gain important insight into the complex gas-phase mechanism leading to the identification of intermediates on the singlet PES (Scheme 4). The relative free and activation energy of the main stationary points involved in Scheme 4 are shown in Fig. 5. The dissociation of phenyl radical through a doublet transition state TS14/d to form a (C6H5)P(Se)S–Cd intermediate, INT7/s on a singlet PES has an activation barrier of +9.30 kcal/mol and exergonic by 11.21 kcal/mol.

As shown in Scheme 4, decomposition of INT7/s may proceed via three pathways, all of which lead to the removal of carbon contamination through the elimination of carbon containing fragments. The decomposition pathway, going through the TS15/s transition state with a barrier height of 41.76 kcal/mol, is a CdSe elimination process which involves the dissociation of Cd–S and P–Se bonds from INT7/s. The CdSe product is located at 20.98 kcal/mol below the reactant.

Decomposition of INT7/s may also proceed through a singlet transition state, TS16/s, having an activation barrier of 41.51 kcal/mol and exergonicity of 14.72 kcal/mol. This leads to the formation of CdS resulting from the elimination of Cd–Se and P–S bonds.

In an alternate dissociation route involving the dissociation of P–S and P–Se bonds, INT7/s gives rise to the formation of a ternary CdSexS1−x. This process is associated with an activation barrier of 41.57 kcal/mol and passes through a singlet transition state TS17/s. The resulting product being 3.42 kcal/mol below INT7/s is ∼18 and ∼11 kcal/mol less stable than the CdSe and CdS dissociation pathway, respectively.

However, CdSe is comparable, located only at 0.25 and 0.19 kcal/mol higher than CdS and ternary CdSexS1−x. Therefore one of the three pathways is not overwhelming to the other but instead competing even if CdS dissociation is a little more favourable. The rate constants along CdS pathway were 1.53 × 10−3 s−1 and 2.32 × 10−5 mol L−1 s−1 (Table 2). Moreover, all the reactions were predicted to be exergonic, ranging from ~ 3–21 kcal/mol. However, the results further suggested that the formation of CdSe is the most stable species on the reaction PES.

In order to provide a direct comparison of activation energy data for a phenylphosphinato complex and its isopropyl analogue, the Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 complex was prepared as a model for Cd[(iPr)2PSSe]2 complex. Precedent for the modelling of phenyl complex is provided by the virtually identical decomposition patterns for the isopropyl complex [42]. DFT results for phenyl group could then be compared to our previously reported data for the isopropyl complex [42]. The activation barrier and reaction energy of the two precursors are presented in Table 3.

The kinetics and thermodynamics of organic and inorganic substituents, and radical reaction pathways may be affected by the size of structural features of either the substrate or the dissociation species. Since any homogeneous decomposition of electron transfer reaction requires appropriate orbital overlap, features that diminish such overlap will reduce the corresponding rate constants. Increasing substitution across the phosphinato complex, increases the activation barrier of the phenyl group, which are significantly greater than the isopropyl analogue. This suggests that the steric congestion afforded by this bulky substituent imposes significant energy on the electron transfer processes. Thus increased alkyl substitution may increase the chemical reaction of the decomposition process and decrease the activation barrier. Therefore, the kinetic stabilities of the resulting ligands depend on the steric congestion about the central phosphorus; more congested compounds are resistant to decomposition, while those with more accessible phosphorus centres react rapidly.

Moreover, the activation barrier data of the phenyl and isopropyl group may also suggest that the C–Ph bond is more difficult to break than the C–i Pr bond. This is consistent with the homolytic bond strength of the C–i Pr moieties [42]. If C–i Pr bond cleavage were involved in the rate determining step, phenyl complex would be expected to require higher deposition temperatures relative to the isopropyl complex. The stronger C–Ph bond may also affect growth rate and composition of the deposited films. Additionally, these data suggest that replacing the phenyl moiety with a group that will cleave more readily could decrease the deposition temperature and improve the compositional characteristics of the cadmium chalcogenides films.

Spin density analysis

The spin density distribution map of some intermediates and transition states complexes obtained on the doublet PES has been explored on the M06/6-31(d) level of theory.

In Fig. 6a–c, most of the spin densities are distributed on the ligand with less metal contribution. As shown in Fig. 6d, the spin density is entirely distributed on the cadmium atom that coordinates to the ligand.

In Fig. 7a–c, additional spin density is symmetrically delocalised on the phenyl group with little or no spin on the phosphorus atom.

In Fig. 8a–c, the spin density is exclusively localised on the selenium atom with less metal contribution. Additional spin density is symmetrically delocalised on the phenyl group that coordinate to the phosphorus atom.

Orbital analysis

The single occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) analysis of some intermediates and transition states complexes has also been explored at the same level of theory. In Fig. 9a–c, the electron density distribution on the cadmium atom resembles that of d-xy orbital; a significant contribution from the ligand was also observed. The SOMO of (C6H5)2PSSe–Cd+ complex shows a strong localisation of electron density on the cadmium atom as compare to the ligand.

Conclusion

The Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 complex was tested to determine its suitability as a single-source precursor for cadmium chalcogenides thin films. The decomposition of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 as a single source precursor, is investigated using density functional theory at the M06/LACVP* level. Kinetically, the dominant pathways for the gas-phase decomposition of Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 were found to be CdS elimination pathways on both the singlet and the doublet PESs. However, on the basis of the dissociation energy of the reactions and with the detailed identification of the reaction intermediates, it is clearly shown that CdSe elimination pathways are the dominant pathways on both the singlet and the doublet PESs. Comparison of energetics of the phenyl group to the isopropyl analogue, allows evaluation of the effect of the phosphinato bond dissociation energy on final decomposition products. The isopropyl precursor is superior to phenyl for barrier deposition due the tendency of the stronger phosphinato bond of phenyl to result in dissociation of the C–Ph fragments. The exploration of chemical kinetics and the construction of global potential energy surfaces for the decomposition of SSPs are believed to provide a comprehensive fundamental molecular level understanding of the reaction mechanism involved in the chemical vapour deposition.

References

Edmundson RS (1996) The chemistry of organophosphorus compounds. Ter- and Quinque-valent phosphorus acids and their derivatives. John Wiley, New York, pp 397–494

Artem’ev AV, Gusarova NK, Malysheva SF, Mamatyuk VI, Gatilov YV, Ushakov IA, Trofimov BA (2010) One-pot atom-economic synthesis of thioselenophosphinates via a new multicomponent reaction of secondary phosphanes with elemental sulphur, selenium, and amines. Eur J Org Chem 2010:6157–6160

Artem’ev AV, Gusarova NK, Bagryanskaya IY, Doronina EP, Verkhoturova SI, Sidorkin VF, Trofimov BA (2013) Alkali metal thioselenophosphinates, M[SeSPR2]: one pot multicomponent synthesis, DFT study, and synthetic application. Eur J Inorg Chem 2013:415–426

Artem’ev AV, Malysheva SF, Korocheva AO, Gatilov YV, Mamatyuk VI, Gusarova NK (2011) Novel atom-economic synthesis of thioselenophosphinates via three-component reaction between secondary phosphine sulphides, elemental selenium, and amines. J Sulphur Chem 32(6):599–610

Artem’ev AV, Gusarova NK, Malysheva SF, Trofimov BA (2011) Diselenophosphinates synthesis and applications. Org Prep Proced Int 43:381–449

Artem’ev AV, Shagun VA, Gusarova NK, Liu CW, Liao JH, Gatilov YV, Trofimov BA (2014) DFT study and dynamic NMR evidence for cis-trans conformational isomerism in square planar Ni(II) thioselenophosphinate, Ni(SeSPPh2)2. J Organomet Chem 768:151–156

Malik MA, Afzaal M, O’Brien P (2010) Precursor chemistry for main group elements in semiconducting materials. Chem Rev 110:4417–4446

Fan D, Afzaal M, Mallik MA, Nguyen CQ, O’Brien P, Thomas PJ (2007) Using coordination chemistry to develop new routes to semiconductor and other materials. Coord Chem Rev 251:1878–1888

Panneerselvam A, Nguyen CQ, Waters J, Malik MA, O’Brien P, Raftery J (2008) Ligand influence on the formation of P/Se semiconductor materials from metal-organic complexes. Dalton Trans 4499–4506

Maneeprakorn W, Nguyen CQ, Malik MA, O’Brien P, Raftery J (2009) Synthesis of the nickel selenophosphinates [Ni(Se2PR2)2] (R = iPr, tBu and Ph) and their use as single source precursors for the deposition of nickel phosphide or nickel selenide nanoparticles. Dalton Trans, 2103–2108. doi:10.1039/B816903A

Boehme C, Wipff G (1999) Dithiophosphinate complexes of trivalent lanthanide cations: consequences of counterions and coordination number for binding energies and selectivity. A theoretical study. Inorg Chem 38:5734–5741

Haiduc I (2001) Thiophosphorus and related ligands in coordination, organometallic and supramolecular chemistry. A personal account. J Organomet Chem 623:29–42

Vardan VL, Uskov EM, Korol’kov IV, Larionov SV (2009) Synthesis and luminescent properties of the complexes EuL(i-Bu2PS2)2(NO3) (L = Phen, 2,2′-Bipy, 4,4′-Bipy). Russ J Gen Chem 79:228–231

Lobana TS, Wang J-C, Liu CW (2007) Recent advances in the coordination chemistry of diselenophosphates and allied ligands. Coord Chem Rev 251:91–110

Liao P-K, Shi D-R, Liao J-H, Liu CW, Artem’ev AV, Kuimov VA, Gusarova NK, Trofimov BA (2012) Facile self-assembly synthesis and characterization of diselenophosphinato octanuclear cui clusters inscribed in a twelve-vertex selenium polyhedron. Eur J Inorg Chem 2012:4921–4929

Jhang R-Y, Liao J-H, Liu CW, Kuimov VA, Gusarova NK, Artem’ev AV (2014) A new convenient synthetic route to metal diselenophosphinates: Synthesis and characterization of [M2(Se2PPh2)4] (M = Zn, Cd and Hg) complexes. J Org Chem 758:60–64

Shiu R-Y, Liao J-H, Liu CW, Kuimov VA, Gusarova NK, Artem’ev AV (2014) Synthesis and comparative structural study of tris-chelated Sb(III), Bi(III) and Cr(III) diselenophosphinato complexes. Polyhedron 68:53–59

Jhang R-Y, Liao J-H, Liu CW, Artem’ev AV, Kuimov VA (2015) Synthesis of the first chalcogen-centered diselenophosphinato Zn(II) clusters, [Zn4(μ 4-X){Se2PR2}6] (X = S or Se), and a zigzag polymer {ZnBr(μ-Se2PR2)[PyNO]}. J Org Chem 781:72–76

Kuchen W, Knop B (1964) Diethylselenothiophosphinic acid derivatives. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 3:507

Kuchen W, Knop B (1966) Zur Kenntnis der Organophosphorverbindungen, IX. Über die Phosphinsäuren (C2H5)2P(S)SeH bzw. (C2H5)2P(Se)SeH und ihre Derivate. Chem Ber 99:1663–1672

Kimura T, Murai T (2005) P-chiral phosphinoselenoic chlorides and phosphinochalcogenoselenoic acid esters: synthesis, characterization, and conformational studies. J Org Chem 70:952–959

Hertel H, Kuchen W (1971) Metallkomplexe der Phosphinsäuren, VI. Über die Elektronenspektren von Thio- und Selenophosphinato-Komplexen des Chroms(III). Chem Ber 104:1735–1739

Esperas S, Husebye S (1973) The crystal and molecular structure of diethylthioselenophosphinatothallium(i). Acta Chem Scand 27:3355–3364

Kato S, Goto M, Hattori R, Nishiwaki K, Mizuta M, Ishida M (1985) Multistep synthesis of organylammonium thioselenophosphinates. Chem Ber 118:1668–1683

Skrzypczynski Z, Michalski J (1988) Multistep synthesis of optically active triethylammonium tertbutylphenylthioselenophosphinate. J Org Chem 53:4549–4551

Liu C, Wu PC, Sun T, Dai L, Ye Y, Ma R, Qin G (2009) Synthesis of high quality n-type CdSe nanobelts and their applications in nanodevices. J Phys Chem C 113:14478

Jie JS, Zhang WJ, Jiang Y, Lee ST (2006) Transport properties of single-crystal CdS Nano ribbons. Appl Phys Lett 89:223117

Jiang Y, Zhang WJ, Jie JS, Meng XM, Fan X, Lee ST (2007) Photo response properties of CdSe single- nano ribbon photo detectors. Adv Funct Mater 17:1795

Shen G, Chen D (2010) One-dimensional nanostructures for photo detectors. Recent Pat Nanotechnol 4:20

Liu C, Dai L, Ye Y, Sun T, Peng RG, Wen X, Wu PC, Qin GG (2010) High-efficiency colour tunable n-CdSxSe1-x/p + -Si parallel-nanobelts heterojunction light-emitting diodes. J Mater Chem 20:5011

Ye Y, Dai L, Wu PC, Liu C, Sun T, Ma RM, Qin GG (2009) Schottky junction photovoltaic devices based on CdS single nanobelts. Nanotechnology 20:375202

Ye Y, Gan L, Dai L, Dai Y, Guo XF, Meng H, Yu B, Shi ZJ, Shang KP, Qin GG (2011) A simple and scalable graphene patterning method and its application in CdSe nanobelt/graphene Schottky junction solar cells. Nanoscale 3:1477–1481

Wu P, Ye Y, Sun T, Peng R, Wen X, Xu W, Liu C, Dai L (2009) Ultrahigh-Performance Inverters Based on CdS Nanobelts. ACS Nano 3:3138

Yeom D, Keem K, Kang J, Jeong DY, Yoon C, Kim D, Kim S (2008) NOT and NAND logic circuits composed of top-gate ZnO nanowire field-effect transistors with high-k Al2O3 gate layers. Nanotechnology 19:265202

Chong LW, Chien HT, Lee YL (2010) Assembly of CdSe onto mesoporous TiO2 films induced by a self-assembled monolayer for quantum dot-sensitized solar cell applications. J Power Sources 195:5109

Celik D, Krueger M, Veit C, Schleiermacher HF, Zimmermann B, Allard S, Dumsch I, Scherf U, Rauscher F, Niyamakom P (2012) Performance enhancement of CdSe nanorod-polymer based hybrid solar cells utilizing a novel combination of post-synthetic nanoparticle surface treatments. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 98:433

Roth M (1989) Advantages of limitations of Cadmium Selenide room temperature gamma ray detectors. Nucl Instrum Methods A 283:291

Du L, Lei Y (2012) Synthesis and photovoltaic characteristic of n-type CdSe nanobelts. Mater Lett 73:95

Soundararajan D, Yoon JK, Kim YI, Kwon JS, Park CW, Kim SH, Ko JM (2009) Grown Directly on FTO Coated Glass: synthesis and Characterization. Int J Electrochem Sci 4:1628

Xie R, Peng X (2009) Synthesis of Cu-doped InP nanocrystals (d-dots) with ZnSe diffusion barrier as efficient and colour-tunable NIR emitters. J Am Chem Soc 131:10645

Gan C, Zhang Y, Battaglia D, Pang X, Xiao M (2008) Fluorescence lifetime of Mn-doped ZnSe quantum dots with size dependence. Appl Phys Lett 92:241111

Opoku F, Asare-Donkor NK, Adimado AA (2014) Density functional theory (DFT) study of the gas-phase decomposition of the Cd[(iPr)2PSSe]2 single-source precursor for the CVD of binary and ternary cadmium chalcogenides. J Mol Model 20:2484–2495

Opoku F, Asare-Donkor NK, Adimado AA (2015) Theoretical study of the gas-phase decomposition of Pb[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 single-source precursor for the chemical vapour deposition of binary and ternary lead chalcogenides. Can J Chem 93:1–9

Opoku F, Asare-Donkor NK, Adimado AA (2015) Theoretical studies of the decomposition of Zn[(iPr)2PSSe]2 single-source precursor in the gas phase for the chemical vapour deposition of binary and ternary zinc chalcogenides. Comp Theo Chem 1058:1–11

Opoku F, Asare-Donkor NK, Adimado AA (2015) Quantum mechanical study of the kinetics, mechanisms and thermodynamics of the gas-phase decomposition of Pb[(iPr)2PSSe]2 single source precursor. J Org Chem 787:33–43

Opoku F, Asare-Donkor NK, Adimado AA (2015) Thermal decomposition of Zn[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 single-source precursor for the chemical vapour deposition of binary and ternary zinc chalcogenides: a theoretical study. Springer Plus 4(266):1–13

Spartan, Wavefunction, Inc, 18401 Von Karman Ave., # 370, Irvine, CA, 92715, USA

Hay PJ, Wadt WRJ (1985) Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms Sc to Hg. Chem Phys 82:270–283

Wadt WR, Hay PJ (1985) Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J Chem Phys 82:284–298

Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2008) The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor Chem Account 120:215–241

Zhao Y, Pu J, Lynch BJ, Truhlar DG (2004) Tests of second-generation and third-generation density functionals for thermochemical kinetics. J Chem. Phy. 6:673–676

Clark M, Cramer RD, Opdenbosch NV (1989) Validation of the general purpose tripos 5.2 force field. J Comp Chem 10:982–1012

Benson SW (1960) The Foundations of Chemical Kinetics. McGraw-Hill, New York

Glasstone S, Laidler KJ, Eyring H (1941) The Theory of Rate Processes. McGraw-Hill, New York

Akhtar J, Afzaal M, Vincent M, Burton N, Raftery J, Hillier I, O’Brien P (2011) Understanding the decomposition pathways of mixed sulphur/selenium lead phosphinato precursor explaining the formation of lead selenide. J Phys Chem C 115(34):16904–16909

Cupertino D, Birdsall DJ, Slwain AMZ, Woollins JD (1999) Inorg Chim Acta 290:1

Authors’ contributions

NKA and AAA proposed and designed research subject; FO carried out the computation studies and wrote the paper. NKA and AAA helped in the result and discussion and edit the final manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the National Council for tertiary Education (NTCE), Ghana for a research grant under the Teaching and Learning Innovation Fund (TALIF-KNUSTR/3/005/2005). We are also grateful to the Computational Quantum Chemistry Laboratory at the Department of Chemistry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana for the use of their facilities for this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Opoku, F., Asare-Donkor, N.K. & Adimado, A.A. A comprehensive understanding of the chemical vapour deposition of cadmium chalcogenides using Cd[(C6H5)2PSSe]2 single-source precursor: a density functional theory approach. Chemistry Central Journal 10, 4 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-016-0146-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-016-0146-3