Abstract

Introduction

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) can reveal the metabolic activity of malignant tumors. Recent advances gained from molecular studies suggest that tumor biology can be a good predictor of prognosis in breast cancer. We compared the ability of maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) derived by FDG-PET with tumor burden in predicting tumor recurrence for patients with breast cancer.

Methods

496 patients with breast cancer who underwent preoperative FDG-PET between April 2004 and May 2009 were retrospectively identified. SUVmax was obtained by FDG-PET, and the cutoff point was defined using a time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curve for recurrence-free survival (RFS). The primary endpoint was RFS.

Results

In multivariate analysis for RFS, SUVmax carried independent prognostic significance (hazard ratio, 2.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.20 to 4.76; P = 0.012). When the patients were classified into four groups according to the combined factors of tumor size (≤2 cm versus >2 cm) and SUVmax (<4 versus ≥4), RFS differed significantly (P < 0.001). Similarly, SUVmax had prognostic value in combination with nodal status (negative versus positive) or stage (I versus II and III) (P < 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively). In hormone receptor–positive disease, SUVmax remained a significant prognostic factor for RFS based on multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

Our results highlight the prognostic value of FDG-PET in prediction of tumor relapse for patients with breast cancer. Particularly in patients with hormone receptor–positive disease, the tumor metabolic information provided by FDG-PET is more significantly correlated with prognosis than tumor burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tumor burden, represented by tumor size and the number of involved lymph nodes, is the most important prognostic factor for breast cancer recurrence [1],[2] because advanced-stage tumors are more likely to have distant metastases. In the genomics era, rapid advances in translational research have greatly improved our understanding of breast cancer biology. This work provides us with the tools that can identify intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer and discriminate a prognosis according to subtype [3], highlighting the clinical availability of tumor biology in breast cancer prognosis [4],[5]. These studies provide evidence that small tumors with undesirable biology can lead to a worse prognosis than large tumors with favorable biology. Therefore, to deliver more effective personalized medical treatment to individual patients, there is an increasing need to evaluate cancer with tumor biology integration, as well as simple anatomical staging.

18F-fluorodexoyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is a useful tool in the prediction of tumor recurrence, as well as for providing relevant anatomical information, because this imaging modality reflects tumor biology well [6],[7]. It is one of the new tools that can capture tumor biology without an invasive procedure. The degree of FDG uptake reflects the metabolic characteristics of tumors and can be used as a prognostic factor in various malignancies. In breast cancer, studies have shown the contribution of tumor biology to increased FDG uptake [8]-[10] and have demonstrated that FDG uptake is associated with aggressive tumor characteristics [11],[12].

As like other molecular markers were compared or integrated with tumor burden, we wondered whether the prognostic power of current clinical parameters improves when the biologic information of FDG-PET is combined with them. In this retrospective study, we evaluated the potential of FDG uptake as a prognostic indicator in breast cancer as compared to, and in combination with, tumor burden.

Methods

Patient selection

Between April 2004 and May 2009, 1,053 women consecutively underwent surgery for breast cancer at our institution. Of these 1,053 patients, 835 underwent preoperative FDG-PET as a part of their routine preoperative staging. Patients were excluded on the basis of the following criteria: known bilateral breast cancer (n = 31), preoperative chemotherapy (because chemotherapy can affect tumor characteristics related to FDG uptake) (n = 94), ductal carcinoma in situ (n = 135) and distant metastases at initial assessment (n = 42). Among these patients, 501 women of interest were identified. Patients missing data for any immunohistochemical marker were excluded (n = 3). Patients with an immunohistochemistry (IHC) scores of 2+ for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), but without fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) results for HER2 amplification, were also excluded (n = 2). Data for the remaining 496 patients were entered into the analysis (Figure 1).

For the immunohistochemical study of four markers, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections obtained from the surgical specimens were stained with appropriate antibodies for estrogen receptor (ER) (Novocastra; Leica Microsystems, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), progesterone receptor (PR) (Novocastra; Leica Microsystems), HER2 (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) and Ki-67 (MIB-1; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). For HER2 evaluation, membranous staining was graded with a score of 0, 1+, 2+ or 3+ [13]. HER2 status was considered positive with a score of 3+ and negative with a score of 0 or 1+. Tumors with a score of 2+ were sent for FISH testing performed using the PathVysion HER-2 DNA Probe Kit (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA).

The staging was performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system [14]. The Elston-Ellis modification of the Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grading system was used for tumor grading. Adjuvant systemic therapy and/or radiotherapy were administered according to the standard guidelines based on patient age, primary tumor characteristics and axillary lymph node status. Endocrine therapy was given to patients whose tumors were positive for hormone receptor expression. The follow-up protocol included planned regular visits every 6 months, and missed appointments were followed by telephone calls to minimize the number of patients lost to follow-up and improve the accuracy of the survival data. The final update to the clinical database was made in December 2013.

The institutional review board (IRB) of Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, approved the study in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The IRB granted a waiver of written documentation of informed consent from all participants because of the retrospective study design.

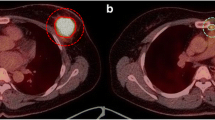

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

Prior to undergoing FDG-PET, each patient was asked to fast for a minimum of 8 hours, and blood glucose levels were controlled to <130 mg/dl. Patients received an intravenous injection of 18F-FDG (0.14 MBq) in the arm contralateral to the primary tumor. Sixty minutes after injection of 18F-FDG, whole-body emission scans were obtained using a Philips Allegro PET camera (Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA). Scans were obtained with the patient in the supine position with the arms raised. Attenuation-corrected transaxial images were reconstructed with an iterative transmission algorithm (row-action maximum likelihood three-dimensional protocol) using a three-dimensional image filter in a 128 × 128 matrix. For semiquantitative evaluations, maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was calculated by measuring the 18F-FDG absorption by tumors in the region of interest (ROI) using the following equation: SUVmax = (maximal radioactivity concentration in the ROI (μCi/g)/injected dose (μCi)/patient’s weight (kg)). All FDG-PET scans were reviewed by two nuclear medicine radiologists who were blinded to survival data. SUVmax was obtained at the time of the imaging procedure.

Statistical analysis

The cutoff point of SUVmax was obtained by using the time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Age is presented in the study as median value with a range and was compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. Discrete variables were compared by performing a χ2 test. The primary endpoint was recurrence-free survival (RFS), which was measured from the date of the first curative surgery to the date of the first tumor recurrence, including locoregional recurrence or distant metastasis or death. Breast cancer–specific survival (BCSS) was measured from the date of the first curative surgery to the date of the last follow-up or until death due to breast cancer during the follow-up period. The Kaplan-Meier method was utilized to estimate RFS or BCSS. Using Harrell c-statistics [15], the concordance index (c-index) was calculated to measure the concordance for time-to event data, in which increasing values between 0.5 and 1.0 indicated improved prediction. The significant prognostic factors associated with RFS were selected based on the c-index (Additional file 1). The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for multivariable survival analysis. To assess the additional prognostic value of SUVmax, we used changes in the likelihood ratio values (LR − Δχ2) to quantitatively measure the relative amount of information for SUVmax compared to the model without SUVmax. The cutoff value of young age was defined as 35 years in accordance with a previous Korean study [16]. SPSS version 18 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and R [17] were used to perform these analyses. Statistical significance was defined by a P-value <0.05 or a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

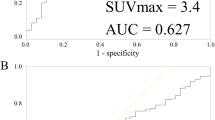

Definition of cutoff point for maximum standardized uptake value

The cutoff point of SUVmax was obtained using the time-dependent ROC. The time-dependent ROC curve for SUVmax in relation to RFS yielded an area under the curve of 0.673 (95% CI, 0.588 to 0.753) (Additional file 2). Youden’s index was the highest for SUVmax of 4.2. Considering the clinical application, we defined the SUVmax cutoff as 4.

Patient characteristics

A total of 496 patients with breast cancer were included in the analysis. The median age of the cohort was 48 years (range, 25-80 years). The median and mean SUVmax were 4.3 ± 3.1 and 3.2 (range, 0.3-32.9), respectively. When patients were divided into two groups according to SUVmax, these groups differed significantly in T stage, N stage, AJCC stage, which represent tumor burden. They also differed in characteristics reflecting tumor biology, including histologic grade, ER, PR, HER2, and Ki67. In considering the distribution of tumor subtypes, the group with high SUVmax had a higher rate of luminal B, HER2, and triple-negative subtypes. In contrast, the proportion of patients with the luminal A subtype was relatively low in the group with high SUVmax (Table 1). A higher rate of mastectomy was noted in the group with high SUVmax (Table 1).

Survival outcome

At a median follow-up of 6.03 years, tumors had recurred in 40 patients. There were 13 patients with locoregional recurrences, 25 with distant metastases and 2 with combined local recurrence and distant metastases. During the follow-up period, 11 deaths occurred, 8 of which were breast cancer–specific and 3 of which were not breast cancer–specific. The probability of RFS at 6 years was 95.6% for patients with low SUVmax and 86.8% for patients with high SUVmax. High SUVmax was significantly predictive of decreased RFS (P < 0.001 by log-rank test) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, patients with high SUVmax showed a reduced BCSS (P = 0.007 by log-rank test) (Figure 2B). When adjusted for age of diagnosis, T stage, nodal status and ER status using the Cox proportional hazards regression model, high SUVmax was significantly associated with risk of tumor relapse (hazard ratio, 2.39, 95% CI, 1.20 to 4.76) (Table 2). For this model, the Harrell c-index was 0.745. The c-index for the multivariate model without SUVmax was 0.724. The LR-Δχ2 showed a significant improvement of the additional prognostic utility of SUVmax.

Prognostic value of a combined maximum standardized uptake values with tumor burden

Four patient groups were classified according to SUVmax and tumor size: (1) tumor size ≤2 cm and SUVmax <4; (2) tumor size >2 cm and SUVmax <4; (3) tumor size ≤2 cm and SUVmax ≥4; and (4) tumor size >2 cm and SUVmax ≥4. The RFS of the four groups differed significantly (P < 0.001) (Figure 3A). Within the groups of large tumor size (>2 cm) and small tumor size (≤2 cm), RFS differed significantly according to the SUVmax (P = 0.049 and P = 0.009, respectively). Conversely, within the groups of high SUVmax and low SUVmax, RFS did not differ according to tumor size (P = 0.350 and P = 0.096, respectively).

Furthermore, SUVmax was significantly predictive of RFS in combination with nodal status (P < 0.001) (Figure 3B). Node-positive patients with high SUVmax had worse outcomes, whereas node-negative patients with low SUVmax had better outcomes. Similarly, SUVmax combined with stage was significantly correlated with RFS (P = 0.001) (Figure 3C).

Maximum standardized uptake values in luminal breast cancer

After the patients were divided into three subtypes (luminal, HER2 or triple-negative), multivariate analysis for RFS was performed in each subtype. In luminal subtypes, which were defined as hormone receptor–positive breast cancer (ER-positive and/or PR-positive), SUVmax was found to be a significant prognostic factor for RFS based on multivariate analysis (Table 3). However, in HER2 or triple-negative subtypes, SUVmax was not an independent prognostic factor (Additional file 3).

The prognostic value of SUVmax combined with tumor burden was also assessed in hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. When the patients were classified into four groups according to both combined factors, RFS differed significantly (P < 0.001) (Figure 4A). There was no difference in RFS when patients were stratified by tumor size within the groups with high SUVmax and low SUVmax (P = 0.950 and P = 0.688, respectively). However, within the groups with small tumor sizes (≤2 cm), a significantly reduced RFS was found in patients with high SUVmax (P = 0.044). In patients with large tumor sizes (>2 cm), RFS did not differ significantly according to SUVmax (P = 0.065), possibly due to the limited number of patients (n = 122).

Kaplan-Meier plots for recurrence-free survival according to a combined factor that includes both tumor burden and SUV max in hormone receptor-positive cancer. (A) Tumor size (P = 0.028) (B) Node status (P = 0.006) (C) Stage (P = 0.029). SUVmax, Maximum standardized uptake value. All P-values were calculated by the log-rank test.

In luminal breast cancer, SUVmax was still predictive of RFS in combination with nodal status (negative vs. positive) and stage (I vs. II and III) (P < 0.006 and P = 0.029, respectively) (Figure 4B and 4C).

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate the ability of SUVmax to predict clinical outcomes in a large cohort of breast cancer patients who underwent FDG-PET. SUVmax carried independent prognostic significance in multivariate analysis for prediction of tumor relapse. Attempts to validate FDG uptake as a prognostic indicator in breast cancer have been made in previous studies [18]-[20]. However, failure to be validated as an independent prognostic factor [18], small number of patients [19] and analysis based on a web-accessible risk-assessment model (Adjuvant! Online) [20] were limitations. Despite these limitations, those studies provided evidence that that FDG uptake has potential as a prognostic marker in breast cancer, which seems reasonable because tumors with increased glucose uptake show aggressive tumor behaviors and high proliferative propensities [8]-[10]. Other studies have consistently shown that breast cancer with a high SUVmax is associated with ER negativity, high histologic grade, high Ki67 and the triple-negative subtype [10]-[12], which is consistent with our data (Table 1). In support of the clinical significance of tumor biology–associated glucose metabolism are recent studies showing that several signaling pathways implicated in cell proliferation and tumor progression also regulate metabolic pathways [21]-[24].

Particularly in the survival analyses using a combined factor with SUVmax and tumor burden, SUVmax showed a superior prediction of RFS in breast cancer compared with clinical tumor load. After four groups were formed using SUVmax and tumor size, within the groups with high or low SUVmax, tumor size did not provide additional prognostic differentiation (Figure 3A). However, within the groups with large or small tumor size, SUVmax improved the prediction of RFS. Similar results were seen when SUVmax was combined with nodal status or AJCC stage (Figures 3B and 3C). These findings suggest that when tumor biology is considered in addition to clinical tumor burden, prediction of breast cancer prognosis can be improved. SUVmax could provide powerful prognostic information about tumor relapse that is superior to considering only tumor burden, similar to the contribution of molecular subtype.

There are established molecular predictors reflecting tumor biology and predicting prognosis in breast cancer. Although the reason that the multigene assays are actively utilized for ER-positive disease has not been fully clarified, authors of meta-analyses of various multigene breast cancer signatures concluded that the prognostic values of the signatures are comparable when evaluated in hormone receptor–positive breast cancers, presumably due to the fact that the proliferation modules within these diverse gene signatures are a common driving force behind their overall prognostic performance [25],[26]. By contrast, hormone receptor–negative breast cancers are more proliferative and are usually classified as high risk or are not the appropriate target population for these prognostic signatures [25],[26]. In the same context, our results show that the prognostic significance of SUVmax is distinct for luminal tumors (Table 3, Figure 4).

Furthermore, the mean SUVmax for the luminal subtype was the lowest, whereas the values for the HER2 and triple-negative subtypes were comparatively higher (Additional file 4). This finding is concordant with previous reports comparing SUVmax between the IHC-defined subtypes [27]. It seems reasonable that HER2-positive or triple-negative tumors would show increased accumulation of FDG, because these tumors have an aggressive phenotype and are associated with a high rate of proliferation, high Ki67 concentration and high histologic grades. These associations between aggressive markers and high SUVmax were concordantly observed in our study (Table 1). Because HER2-positive or triple-negative tumors generally show high SUVmax, this may also lead to a reduced prognostic significance of SUVmax in these kinds of tumors.

We acknowledge several limitations inherent in our study’s retrospective design. We were unable to control for variations in adjuvant therapy that may have influenced survival outcomes. Compared to the low SUVmax group, the patients in the high SUVmax group received more chemotherapy and less endocrine therapy, likely because they had more advanced stage disease and ER negativity. The cutoff point for SUVmax defined within a single cohort also needs to be validated in an external cohort. However, there was not a significant difference in the number of patients who received radiation treatment between the high SUVmax group and the low SUVmax group. There was also no survival difference between patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy (Additional file 1).

Conclusions

Our study highlights the prognostic value of FDG-PET in predicting tumor relapse for breast cancer patients. We provide evidence supporting the potential utility of FDG-PET in combination with clinical tumor burden for the assessment of prognosis as well as evaluation of tumor location in patients with breast cancer. These results lay the groundwork for future studies on the prognostic implication of SUVmax for breast cancer treatment.

Additional files

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- BCSS:

-

Breast cancer–specific survival

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- c-index:

-

Concordance index

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- FDG-PET:

-

18F-fluorodexoyglucose positron emission tomography

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- RFS:

-

Recurrence-free survival

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- SUVmax:

-

Maximum standardized uptake value

References

Demicheli R, Abbattista A, Miceli R, Valagussa P, Bonadonna G: Time distribution of the recurrence risk for breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy: further support about the concept of tumor dormancy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996, 41: 177-185. 10.1007/BF01807163.

Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE: Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989, 63: 181-187. 10.1002/1097-0142(19890101)63:1<181::AID-CNCR2820630129>3.0.CO;2-H.

Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lønning PE, Børresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D: Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000, 406: 747-752. 10.1038/35021093.

Park YH, Lee SJ, Cho EY, Choi YL, Lee JE, Nam SJ, Yang JH, Shin JH, Ko EY, Han BK, Ahn JS, Im YH: Clinical relevance of TNM staging system according to breast cancer subtypes. Ann Oncol. 2011, 22: 1554-1560. 10.1093/annonc/mdq617.

Hernandez-Aya LF, Chavez-MacGregor M, Lei X, Meric-Bernstam F, Buchholz TA, Hsu L, Sahin AA, Do KA, Valero V, Hortobagyi GN, Gonzalez-Angulo AM: Nodal status and clinical outcomes in a large cohort of patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29: 2628-2634. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1877.

Seo S, Hatano E, Higashi T, Hara T, Tada M, Tamaki N, Iwaisako K, Ikai I, Uemoto S: Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts tumor differentiation, P-glycoprotein expression, and outcome after resection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13: 427-433. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1357.

Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Ohja B, Bartolucci AA: The maximum standardized uptake values on positron emission tomography of a non-small cell lung cancer predict stage, recurrence, and survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005, 130: 151-159. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.11.007.

Ueda S, Kondoh N, Tsuda H, Yamamoto S, Asakawa H, Fukatsu K, Kobayashi T, Yamamoto J, Tamura K, Ishida J, Abe Y, Yamamoto M, Mochizuki H: Expression of centromere protein F (CENP-F) associated with higher FDG uptake on PET/CT, detected by cDNA microarray, predicts high-risk patients with primary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008, 8: 384-10.1186/1471-2407-8-384.

Palaskas N, Larson SM, Schultz N, Komisopoulou E, Wong J, Rohle D, Campos C, Yannuzzi N, Osborne JR, Linkov I, Kastenhuber ER, Taschereau R, Plaisier SB, Tran C, Heguy A, Wu H, Sander C, Phelps ME, Brennan C, Port E, Huse JT, Graeber TG, Mellinghoff IK: 18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission tomography marks MYC-overexpressing human basal-like breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2011, 71: 5164-5174. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4633.

Basu S, Chen W, Tchou J, Mavi A, Cermik T, Czerniecki B, Schnall M, Alavi A: Comparison of triple-negative and estrogen receptor-positive/progesterone receptor-positive/HER2-negative breast carcinoma using quantitative fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose/positron emission tomography imaging parameters: a potentially useful method for disease characterization. Cancer. 2008, 112: 995-1000. 10.1002/cncr.23226.

Shimoda W, Hayashi M, Murakami K, Oyama T, Sunagawa M: The relationship between FDG uptake in PET scans and biological behavior in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2007, 14: 260-268. 10.2325/jbcs.14.260.

Mavi A, Cermik TF, Urhan M, Puskulcu H, Basu S, Yu JQ, Zhuang H, Czerniecki B, Alavi A: The effects of estrogen, progesterone, and C-erbB-2 receptor states on 18F-FDG uptake of primary breast cancer lesions. J Nucl Med. 2007, 48: 1266-1272. 10.2967/jnumed.106.037440.

Moeder CB, Giltnane JM, Harigopal M, Molinaro A, Robinson A, Gelmon K, Huntsman D, Camp RL, Rimm DL: Quantitative justification of the change from 10% to 30% for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 scoring in the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines: tumor heterogeneity in breast cancer and its implications for tissue microarray–based assessment of outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 5418-5425. 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8033.

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC): AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edition. Edited by Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. New York: Springer; 2010.

Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB: Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996, 15: 361-387. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4.

Han W, Kang SY, Korean Breast Cancer Society: Relationship between age at diagnosis and outcome of premenopausal breast cancer: age less than 35 years is a reasonable cut-off for defining young age-onset breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010, 119: 193-200. 10.1007/s10549-009-0388-z.

The R Project for Statistical Computing. http://www.r-projet.org.

De Cicco C, Gilardi L, Botteri E, Fracassi SL, Di Dia GA, Botta F, Prisco G, Lombardo D, Rotmensz N, Veronesi U, Paganelli G: Is [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by the primary tumor a prognostic factor in breast cancer?. Breast. 2013, 22: 39-43. 10.1016/j.breast.2012.05.009.

Inoue T, Yutani K, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Shiba E, Noguchi S: Preoperative evaluation of prognosis in breast cancer patients by [18F]2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose-positron emission tomography. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004, 130: 273-278. 10.1007/s00432-003-0536-5.

Ueda S, Tsuda H, Asakawa H, Shigekawa T, Fukatsu K, Kondo N, Yamamoto M, Hama Y, Tamura K, Ishida J, Abe Y, Mochizuki H: Clinicopathological and prognostic relevance of uptake level using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography fusion imaging (18F-FDG PET/CT) in primary breast cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008, 38: 250-258. 10.1093/jjco/hyn019.

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009, 324: 1029-1033. 10.1126/science.1160809.

Schieber MS, Chandel NS: ROS links glucose metabolism to breast cancer stem cell and EMT phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2013, 23: 265-267. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.021.

Levine AJ, Puzio-Kuter AM: The control of the metabolic switch in cancers by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Science. 2010, 330: 1340-1344. 10.1126/science.1193494.

Dang CV: Links between metabolism and cancer. Genes Dev. 2012, 26: 877-890. 10.1101/gad.189365.112.

Wirapati P, Sotiriou C, Kunkel S, Farmer P, Pradervand S, Haibe-Kains B, Desmedt C, Ignatiadis M, Sengstag T, Schütz F, Goldstein DR, Piccart M, Delorenzi M: Meta-analysis of gene expression profiles in breast cancer: toward a unified understanding of breast cancer subtyping and prognosis signatures. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10: R65-10.1186/bcr2124.

Yau C, Sninsky J, Kwok S, Wang A, Degnim A, Ingle JN, Gillett C, Tutt A, Waldman F, Moore D, Esserman L, Benz CC: An optimized five-gene multi-platform predictor of hormone receptor negative and triple negative breast cancer metastatic risk. Breast Cancer Res. 2013, 15: R103-10.1186/bcr3567.

Koo HR, Park JS, Kang KW, Cho N, Chang JM, Bae MS, Kim WH, Lee SH, Kim MY, Kim JY, Seo M, Moon WK: 18F-FDG uptake in breast cancer correlates with immunohistochemically defined subtypes. Eur Radiol. 2014, 24: 610-618. 10.1007/s00330-013-3037-1.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant 2013R1A1A2007759). The final manuscript was prepared with the assistance of BioScience Writers LLC (Houston, TX, USA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical review of the manuscript. SGA and JJ conceived of the study and coordinated the data acquisition and analysis. SGA and JTP principally wrote the manuscript. SGA, JTP and KH mainly performed the analyses. TJJ and YHR performed FDG-PET and obtained SUVmax. HML, HWL, SAL, SMD and EJS performed part of the analysis, contributed to the data and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Sung Gwe Ahn, Jong Tae Park contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

13058_2014_502_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Details of our process for selecting variables and optimizing the multivariate model based on c -index. (DOCX 112 KB)

13058_2014_502_MOESM3_ESM.docx

Additional file 3: 1. Multivariate analysis for recurrence-free survival using the Cox proportional hazards regression model in HER2-positive disease or triple-negative disease. 2. Regimens for adjuvant chemotherapy used in our patients. (DOCX 21 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahn, S.G., Park, J.T., Lee, H.M. et al. Standardized uptake value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for prediction of tumor recurrence in breast cancer beyond tumor burden. Breast Cancer Res 16, 502 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-014-0502-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-014-0502-y