Abstract

Background

The optimal level of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) during mechanical ventilation for COVID-19 pneumonia remains debated and should ideally be guided by responses in both lung volume and perfusion. Capnodynamic monitoring allows both end-expiratory lung volume (\({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\)) and effective pulmonary blood flow (EPBF) to be determined at the bedside with ongoing ventilation.

Methods

Patients with COVID-19-related moderate to severe respiratory failure underwent capnodynamic monitoring of \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF during a step increase in PEEP by 50% above the baseline (PEEPlow to PEEPhigh). The primary outcome was a > 20 mm Hg increase in arterial oxygen tension to inspired fraction of oxygen (P/F) ratio to define responders versus non-responders. Secondary outcomes included changes in physiological dead space and correlations with independently determined recruited lung volume and the recruitment-to-inflation ratio at an instantaneous, single breath decrease in PEEP. Mixed factor ANOVA for group mean differences and correlations by Pearson’s correlation coefficient are reported including their 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Of 27 patients studied, 15 responders increased the P/F ratio by 55 [24–86] mm Hg compared to 12 non-responders (p < 0.01) as PEEPlow (11 ± 2.7 cm H2O) was increased to PEEPhigh (18 ± 3.0 cm H2O). The \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) was 461 [82–839] ml less in responders at PEEPlow (p = 0.02) but not statistically different between groups at PEEPhigh. Responders increased both \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF at PEEPhigh (r = 0.56 [0.18–0.83], p = 0.03). In contrast, non-responders demonstrated a negative correlation (r = − 0.65 [− 0.12 to − 0.89], p = 0.02) with increased lung volume associated with decreased pulmonary perfusion. Decreased (− 0.06 [− 0.02 to − 0.09] %, p < 0.01) dead space was observed in responders. The change in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) correlated with both the recruited lung volume (r = 0.85 [0.69–0.93], p < 0.01) and the recruitment-to-inflation ratio (r = 0.87 [0.74–0.94], p < 0.01).

Conclusions

In mechanically ventilated patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 respiratory failure, improved oxygenation in response to increased PEEP was associated with increased end-expiratory lung volume and pulmonary perfusion. The change in end-expiratory lung volume was positively correlated with the lung volume recruited and the recruitment-to-inflation ratio. This study demonstrates the feasibility of capnodynamic monitoring to assess physiological responses to PEEP at the bedside to facilitate an individualised setting of PEEP.

Trial registration: NCT05082168 (18th October 2021).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The selection of level of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) during invasive mechanical ventilatory support for COVID-19 pneumonia remains debated. A low level PEEP (≤ 10 cm H2O) for COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure was supported by a third of experts in a recent Delphi method consensus statement with half of the panel members remaining neutral without agreement on PEEP titration [1]. In contrast, the updated Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for COVID-19 provided a strong recommendation to use high level of PEEP (> 10 cm H2O) in moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with COVID-19 (C-ARDS) [2]. The static compliance of the respiratory system was highly variable in a large international cohort study of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients [3]. This highlights the importance of adequate monitoring to allow for an individualised PEEP strategy as an identical level of PEEP might either lead to lung recruitment or overdistention depending on the compliance state. The gas exchange abnormalities in C-ARDS result from a range of ventilation/perfusion inequalities with further complexity added by diverse changes over time and in different lung regions [4, 5]. The responses to different levels of PEEP can be expected to be equally diverse and should ideally be guided by assessment of lung recruitability and lung perfusion. The effects of incremental PEEP on aerated lung tissue in C-ARDS have been investigated using computed tomography [6, 7], electrical impedance tomography [8, 9] and lung ultrasound [10]. These techniques require both specialised equipment and procedural expertise. In contrast, capnodynamic monitoring of lung volume and perfusion may be integrated with standard ventilators at the bedside and provides continuous measurements without special respiratory manoeuvres or interruptions [11,12,13,14]. This study aimed to assess the feasibility of capnodynamic monitoring of the responses to increased PEEP on gas exchange in mechanically ventilated patients with moderate to severe C-ARDS. It was hypothesised that in patients responding with increased arterial oxygen tension to inspired fraction of oxygen ratio at high PEEP, capnodynamic monitoring would identify an increase in lung volume with increased or preserved pulmonary blood flow.

Methods

This pragmatic, prospective, observational open study was approved by the South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/ETH00778) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05082168). Patients admitted to Liverpool Hospital ICU between September 2021 and February 2022 were screened for eligibility with verbal consent from the patient’s person responsible. The study is reported as per the STROBE guidelines for observational studies [15] (Additional File 1: Table S1).

Patient management and eligibility

All patients were positive for SARS-Cov2 RNA in real-time PCR assay of a nasopharyngeal swab. Patients received continuous sedation and analgesia and in case of persistent patient-ventilator dyssynchrony, neuromuscular blockade was established. Lung protective ventilation at a tidal volume (Vt) of 6 ml/kg predicted body weight (PBW) with plateau pressures (Pplat) < 30 cm H2O and a respiratory rate (RR) adjusted for permissive hypercarbia (pH > 7.25) was used, with the inspired fraction of oxygen (FiO2) titrated to a peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 88–92%. A pressure-regulated volume-controlled mode was used (Draeger V500, Draeger, Lubeck, Germany or Hamilton C6, Hamilton Medical AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland). The study inclusion criteria were (1) patient identified within 72 h of admission to ICU for confirmed SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia; (2) age > 18 years; (3) moderate or severe ARDS (a ratio of partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) to inspired fraction of oxygen (FiO2) ≤ 200 mm Hg) and receiving invasive ventilatory support with ≥ 5 cm H2O PEEP; (4) fully synchronised with the ventilator; and (5) a recruitment manoeuvre by increasing PEEP to + 50% above the set level warranted in the opinion of the treating clinical team, independent of the study protocol. Exclusion criteria were (1) pneumoperitoneum; (2) pneumomediastinum; (3) undrained pneumothorax or ongoing air leak; (4) haemodynamic instability (> 30% increase in vasopressor over last 6 h or noradrenaline > 0.5 µg/kg/min).

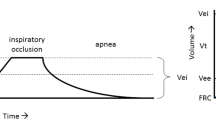

Study procedures

In eligible patients, the endotracheal tube was temporarily clamped in end-inspiration and the standard ventilator changed to the research Servo-I ventilator (Maquet Critical Care, Solna, Sweden) with the FiO2, Vt and PEEP settings unchanged. Patients were ventilated in a volume-controlled mode with a modified breathing pattern in which short expiratory holds were added to 3 out of 9 consecutive breaths to cause cyclical changes in the alveolar partial pressure of CO2 of at least 3 mm Hg. The RR was adjusted to maintain an overall effective RR with the minute ventilation unchanged. The capnodynamic algorithm to derive end-expiratory lung volume (\({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\)) and effective, i.e. non-shunted, pulmonary blood flow (EPBF) has been described in detail elsewhere [11, 14, 16]. In brief, volumetric capnograms are created in real time combining data from a mainstream infrared CO2 sensor (Capnostat®, Philips Respironics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and the integrated flow signal in the Servo-I ventilator. Data were exported to a laptop running dedicated software (MATLAB®, Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) to obtain real-time measurements of \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF (see below, Calculations). The validity of EPBF [13, 16] and \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) [11, 14] against standard methods to monitor cardiac output and functional residual capacity have been reported in clinical studies. After 20 min of baseline PEEP (PEEPlow) recording, an arterial blood gas was obtained and analysed immediately (GEM Premier 5000, Artarmon, New South Wales, Australia). The PEEP was then increased by 50% above baseline level (PEEPhigh) and a repeat arterial blood gas analysis performed after 20 min. The PEEPhigh was then instantaneously reduced to PEEPlow within one breath during a prolonged (5 s) expiration to assess the exhaled tidal volume. The recruited lung volume and the recruitment-to-inflation ratio (R/I ratio) were derived as described below, Calculations. After completion of study procedures, the endotracheal tube was temporarily clamped and the patient was reconnected to the standard ventilator. Study procedures and data were open to the clinical team, and at their discretion, an increased PEEP above the pre-study level was considered in responders.

Patient and clinical characteristics were recorded prior to changing the ventilator. Ventilator data including the \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF were subsequently analysed offline using custom software (www.icumaps.org/visualizer) that calculated the mean values over 30 breaths. The data are reported for the end of baseline PEEPlow and the end of PEEPhigh.

Calculations

The predicted body weight was calculated according to [17]. The physiological dead space (Vd/Vt) was calculated according to the Enghoff equation [18] based on arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) and end-tidal CO2 (ET-CO2). The static compliance of the respiratory system (Crs) was calculated as the Vt divided by the Pplat − PEEP difference, with the latter difference representing the driving pressure, Pdr. The recruited lung volume by the PEEP manoeuvre was assessed as described by Chen et al. [19] during a single breath exhalation. The PEEPhigh was instantaneously decreased to the patient’s PEEPlow in a prolonged expiration and the actual change of end-expiratory lung volume was determined from the difference in expiratory tidal volume before and during the PEEP reduction.

The expected change of end-expiratory lung volume was calculated as the product of the Crs at PEEPlow and the difference in PEEP (PEEPhigh − PEEPlow). The recruited lung volume (∆Volrec) was calculated as the difference between the actual and the expected end-expiratory lung volumes at the rapid PEEP reduction. The recruitment-to-inflation ratio (R/I ratio) was calculated as previously described [19] dividing the compliance of the recruited lung volume by the Crs at PEEPlow.

The capnodynamic method is based on the differential Fick equation for carbon dioxide [12]. With the assumption that the lung volume, pulmonary blood flow and the mixed venous content of CO2 (CvCO2) remain constant during each 9-breath measurement cycle, the created variability in expired CO2 makes it possible to solve the nine capnodynamic equations with the least square method to obtain the three unknown parameters: \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\), CvCO2 and EPBF. The capnodynamic equation describes a mole balance of CO2 between the transport of CO2 to and from the lungs and the rate of change in the CO2 content of the lungs and is expressed as

The FACO2 represents the mean alveolar fraction of CO2 measured at the mid-point of the slope of phase III of the volumetric capnogram [20], n is the current breath, n − 1 is the previous breath, ∆tn is the current breath cycle time, CcCO2n is the content of CO2 in the pulmonary capillary blood calculated from FACO2 and VtCO2n is the volume of CO2 eliminated by a breath. The capnodynamic equation system is applied in a continuous breath-by-breath fashion where every 10th breath is replacing the first one in the nine-breath cycle.

Outcomes

Changes in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF were assessed against the primary outcome of a change in PaO2/FiO2 ratio induced by increased PEEP. An increase in PaO2/FiO2 > 20 mm Hg was used to classify responders versus non-responders [21]. The secondary outcomes included Vd/Vt and correlations to changes in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EBPF, and ∆Volrecr as well as R/I ratio and correlations to changes in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\).

Statistics

No formal sample size calculation was performed for this observational study, and the final sample size was determined by the number of patients admitted to ICU during two surges of the COVID-19 pandemic in south-western Sydney, Australia. Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range, IQR] for normally and non-normally distributed data as determined by the D’Agostino–Pearson normality test. A mixed factor ANOVA with PEEP set as the within-subjects effect and the P/F ratio response set as the between-subjects effect was performed with Greenhouse–Geisser correction for homogeneity of variance. Post hoc testing was performed with Bonferroni correction for repeated measurements and the main effects reported as median differences with their 95% confidence interval for significant findings. Correlations are reported with Pearson’s r and regressions shown including the 95% confidence intervals from 1000 bootstraps. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p value < 0.05. Data were analysed using the R statistical software (version 4.0.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with graphs generated using GraphPad PRISM (version 9.3.1, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

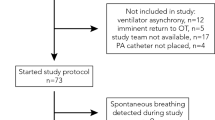

A total of 94 patients with moderate or severe C-ARDS were invasively ventilated in ICU during the study time period with 29 patients enrolled in the study. The study protocol was abandoned in one patient at a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 69 with decision to proceed to veno-venous ECMO. Severe hypercarbia precluded achieving an appropriate cyclic ET-CO2 change for capnodynamic measurements in one patient. Hence, 27 patients were investigated and included in this report. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio increased > 20 mm Hg from PEEPlow to PEEPhigh in 15 patients (responders), while such an improvement was absent in 12 patients (non-responders). The patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. No significant differences between PaO2/FiO2 responders and non-responders were noted at PEEPlow for gas exchange and pulmonary mechanics (Table 2). The PEEPhigh manoeuvre increased PaO2 in responders (mean difference 33 [22–44] mm Hg, p < 0.001) with an increase in PaO2/FiO2 ratio (mean difference 57 [36–78] mm Hg, p = 0.001) (Table 2). The Crs was greater (mean difference 8.5 [3.2–16] mL/cm H2O, p = 0.01) in responders at PEEPhigh with a corresponding decrease in Pdr (mean difference 6.5 [5.5–11] cm H2O, p = 0.005) (Table 2).

The \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) was less in responders (1286 ± 347 ml) compared to non-responders (1746 ± 599 ml) at PEEPlow (mean difference 486 [88–831] mL, p = 0.01) but not at PEEPhigh (1804 ± 462 mL in responders, 2052 ± 652 in non-responders, mean difference 241 [194–682], p = 0.61). These findings remained when \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) was indexed to body surface area (data not shown). The \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) indexed by PBW was 20 ± 5.7 mL/kg and 26 ± 6.5 mL/kg (mean difference 5.8 [1.0–8.5] mL/kg, p < 0.01) at PEEPlow and 28 ± 6.8 mL/kg and 31 ± 7.7 mL/kg (mean difference 2.7 [− 4.6 to 9.9] ml/kg, p = 0.73) at PEEPhigh in responders and non-responders, respectively. The EBPF was not statistically different between non-responders and responders at PEEPlow (4.23 ± 1.67 L/min vs. 4.36 ± 1.59 L/min, p = 0.88) nor at PEEPhigh (4.42 ± 1.61 L/min vs. 4.78 ± 1.61 L/min, p = 0.94). The concomitant changes in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF to increased PEEP in PaO2/FiO2 responders demonstrated a positive correlation (r = 0.56 [0.18–0.83], p = 0.03), i.e. recruitment of lung volume was associated with increased pulmonary perfusion (Fig. 1, left graph). In contrast, non-responders demonstrated a negative correlation (r = − 0.65 [− 0.12 to − 0.89], p = 0.02), i.e. an increased lung volume was associated with decreased pulmonary perfusion (Fig. 1, left graph). In PaO2/FiO2 responders, VdVt decreased from PEEPlow (0.43 ± 0.12) to PEEPhigh (0.36 ± 0.10) (mean difference − 0.06 [− 0.02 to − 0.09], p = 0.001), while no statistically significant difference was observed in non-responders (PEEPlow 0.40 ± 0.08 vs. PEEPhigh 0.43 ± 0.10, p = 0.38). The Vd/Vt responses were further explored by correlating changes in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EBPF. For the 20 patients with reduced Vd/Vt, the increase in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) was significantly correlated with increased or maintained EPBF (r = 0.46 [0.04–0.75], p = 0.04), while the correlation in seven patients with increased Vd/Vt failed to attain statistical significance (r = − 0.29, p = 0.53) (Fig. 1, right graph).

Capnodynamic monitoring of changes in end-expiratory lung volume (∆\({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\)) and effective pulmonary blood flow (∆EPBF) in patients with (solid dots, black lines) or without (open squares, grey lines) an increase in PaO2/FiO2 by > 20 mm Hg following increased PEEP level (left hand graph). Changes in end-expiratory lung volume (∆\({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\)) and effective pulmonary blood flow (∆EPBF) are also shown in patients with (stars, black lines) or without (open circles, grey lines) an improvement in Vd/Vt following increased PEEP (right hand graph). Correlations are shown as Pearson’s regression (solid line) with the 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines)

The change in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) correlated with the ∆Volrec (r = 0.85 [0.69–0.93, p < 0.0001] (Fig. 2) and a positive correlation was demonstrated between the R/I ratio and the change in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) from PEEPlow to PEEPhigh (r = 0.87 [0.74–0.94], p ≤ 0.0001) (Fig. 3). The median R/I ratio for all 27 patients was 1.0 and the PEEP induced change in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) below and above the median R/I ratio was 170 ± 198 mL and 578 ± 176 mL, respectively (mean difference 408 [236–546] mL, p < 0.0001).

Changes in end-expiratory lung volume by capnodynamic monitoring (∆\({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\)) and the recruited lung volume (∆Volrec) assessed based on the exhaled tidal volume at the rapid reduction from PEEPhigh to PEEPlow as previously described [19]. The correlation is shown as Pearson’s regression (solid line) with the 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines)

Changes in end-expiratory lung volume by capnodynamic monitoring (∆\({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\)) and the recruitment-to-inflation ratio assessed at the rapid reduction from PEEPhigh to PEEPlow as previously described [19]. The correlation is shown as Pearson’s regression (solid line) with the 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines)

Discussion

In this pragmatic, observational open study of capnodynamic monitoring in mechanically ventilated patients with moderate to severe C-ARDS, an improved PaO2/FiO2 ratio in response to increased PEEP, was associated with increased end-expiratory lung volume and pulmonary perfusion. The change in end-expiratory lung volume was positively correlated with the lung volume recruited and the recruitment-to-inflation ratio. In patients without an improvement in PaO2/FiO2 ratio, PEEP increased end-expiratory lung volume with a decrease lung perfusion consistent with increased dead space. This study demonstrates the feasibility of capnodynamic monitoring to assess physiological responses to PEEP at the bedside to facilitate an individualised setting of PEEP.

Patients were studied about a week after their COVID-19 diagnosis with the majority developing moderate ARDS. A majority of patients in this study improved the PaO2/FiO2 > 20 mm Hg in response to increased PEEP. Compared to recent observational reports of PEEP interventions in C-ARDS, the Crs was similarly low [7, 22] or lower [6, 23, 24] with Pdr correspondingly higher. Patients in this study were class 2 obese with half having a body mass index above 35. This suggests that the prevalence and degree of obesity leading to an increased load on the chest wall should be considered together with the reduced lung compliance associated with C-ARDS. A lung protective ventilation strategy limiting airway pressures was employed including permissive hypercapnia. The associated moderate respiratory acidosis might have aggravated pulmonary vasoconstriction. The changes in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF in response to increased PEEP should be interpreted with those characteristics of the study cohort in mind.

The \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) at PEEPlow (mean PEEP 8 cm H2O) was overall similar to the range of end-expiratory lung volumes, 1000–1400 mL, at PEEP 5–8 cm H2O reported in C-ARDS [6, 7, 22, 24] and non-COVID ARDS [25] using chest computed tomography. The EPBF, that does not include shunt flow, was numerically consistent with a normal cardiac output reflecting the inclusion criterion of haemodynamic stability prior to study procedures. The increased PaO2/FiO2 in response to PEEPhigh was associated with increases in both \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF and this positive correlation supports an improved ventilation/perfusion matching. The greater \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) is consistent with recruitment of previously non-aerated pulmonary tissue that is in line with the concomitant improvement in Crs and decrease in Pdr. Importantly, a reduced shunt fraction would result in an increased EPBF and this plausibly explains the observed response in gas exchange to PEEPhigh. A PEEPhigh-induced decrease in cardiac output from the typical hyperdynamic haemodynamic state of C-ARDS [26, 27] would reduce the shunt fraction as would recruitment of previously perfused but not ventilated lung areas. The increase in EPBF could furthermore indicate a maintained or potentially increased cardiac output as PEEPhigh reduced pulmonary vascular resistance along with decreased atelectases. A previous study of C-ARDS patients who underwent pulmonary artery catheterisation reported an inverse relation between PaO2/FiO2 and shunt at both low (5 cm H2O) and high (15 cm H2O) PEEP levels without a significant reduction in cardiac output [28]. The improved ventilation/perfusion matching is also supported by the reduced dead space observed in responders. In contrast, patients without a significant improvement of PaO2/FiO2 in response to PEEPhigh demonstrated an increased \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) but decreased EPBF. This is consistent with overstretching the lungs, increased pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular strain that would reduce pulmonary perfusion. While these changes point to increased dead space, the numerical increase in Vd/Vt and the negative correlation between \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF failed, however, to attain statistical significance.

The significant correlation between the change in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and the independently measured ∆Volrec in response to PEEP lends support to the validity of capnodynamic monitoring of lung volumes in C-ARDS. The correlation coefficient was similar to that reported between absolute \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and functional residual capacity in a porcine experimental model [29] and superior to that previously reported in anaesthetised patients [14]. Since tidal volumes in this study were kept unchanged from PEEPlow to PEEPhigh, the increased \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) represents a true recruitment effect. In 6 patients, the \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) failed to increase during PEEPhigh using a threshold of at least + 10% to consider random measurements error. This represents a lack of alveolar recruitment where additional PEEP contributes to increased lung stress without any benefit in gas exchange. The capacity of capnodynamic monitoring at the bedside to facilitate an individualised setting of PEEP warrants further clinical investigation to evaluate if it can contribute to minimising ventilator induced lung injury in C-ARDS and non-COVID ARDS [30].

Haemodynamic changes may affect \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) since CO2 kinetics are dependent on pulmonary blood flow. Experimental observations, however, demonstrate \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF as independent factors in the capnodynamic equation [29] in a wide range of cardiac output states. Within this study, three sets of observations were made for patients who progressed to veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support (Additional File 1: Fig. S1). The \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) remained stable during variable pump flow and native pulmonary perfusion states that corroborates the potential to separately monitor \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF by the capnodynamic algorithm.

The change in \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) was also significantly correlated to alveolar recruitment as indicated by the R/I ratio. The median R/I ratio of 1 was higher compared to other studies reporting a median around 0.7 [10, 31] and higher than the threshold of 0.5 previously used to differentiate poorly from highly recruitable patients in C-ARDS [23, 32] and non-COVID ARDS [19]. Recruitability in acute respiratory failure may be highly variable between patients and over time. In this study, a similar proportion (17/27; 63%) of patients would have been considered highly recruitable by an R/I ratio > 0.5 compared to what has been reported in patients intubated early after ICU admission [23] but higher than that in patients intubated late [32]. Most patients in this study demonstrated low compliance and high recruitability consistent with the high elastance (“H”) phenotype based on recruitability idiosyncratic to C-ARDS [33]. More recent studies have questioned this distinction and instead reported similar patterns in C-ARDS and non-COVID ARDS [34]. Irrespectively, capnodynamic monitoring allowed changes in functional lung volume to be continuously monitored during manoeuvres aimed at alveolar recruitment in C-ARDS.

This study has some important limitations. External validity might be limited by the relatively small sample size, non-consecutive enrolment dependent on availability of the clinical research team and a high proportion of responders to recruitment by increased PEEP. No standard comparators were included for \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) or EPBF since this pragmatic study was primarily designed to evaluate the feasibility of capnodynamic monitoring and validation studies have already been published [14, 29]. Levels of PEEP above the PEEPhigh might be considered for alveolar recruitment but were not investigated for effects on \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and EPBF. The R/I ratio was not measured from the 15–5 cm H2O pressure drop as originally described [19] with less of a pressure difference achieved between PEEPhigh and PEEPlow. A formal assessment of airway opening pressure was not performed. Visual inspection, however, confirmed progressive, steep increases in both volume and pressure curves from the start of a breath.

Conclusion

This pragmatic, observational open study using capnodynamic monitoring in patients with COVID-19 ARDS demonstrated associations between an improved PaO2/FiO2 ratio in response to increased PEEP and increased end-expiratory lung volume and pulmonary perfusion. The change in end-expiratory lung volume was positively correlated with independent measures of recruited lung volume and the recruitment-to-inflation ratio. Capnodynamic monitoring is feasible to assess physiological responses to PEEP at the bedside and could facilitate an individualised level of PEEP during mechanical ventilatory support.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymised data are available upon reasonable request and if approved by the South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee. No custom code was used and software for statistical analysis is stated in Methods and available in the public domain.

Abbreviations

- ∆Volrec :

-

Recruited lung volume

- C-ARDS:

-

COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome

- C rs :

-

Static compliance of the respiratory system

- CvCO2 :

-

Mixed venous carbon dioxide content

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- \({\text{EELV}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) :

-

End-expiratory lung volume by capnometry

- EPBF:

-

Effective pulmonary blood flow

- ET-CO2 :

-

End-tidal carbon dioxide

- FACO2 :

-

Alveolar fraction of carbon dioxide

- FiO2 :

-

Inspiratory fraction of oxygen

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- PaCO2 :

-

Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PaO2 :

-

Arterial partial pressure of oxygen

- PaO2/FiO2 :

-

Arterial partial oxygen pressure to inspired oxygen fraction ratio

- PBW:

-

Predicted body weight

- P dr :

-

Driving pressure

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- P plat :

-

Plateau pressure

- R/I ratio:

-

Recruitment-to-inflation ratio

- RR:

-

Respiratory rate

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SpO2 :

-

Peripheral oxygen saturation

- V d/V t :

-

Physiological dead space

- V t :

-

Tidal volume

References

Nasa P, Azoulay E, Khanna AK, Jain R, Gupta S, Javeri Y, Juneja D, Rangappa P, Sundararajan K, Alhazzani W, et al. Expert consensus statements for the management of COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure using a Delphi method. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):106.

Alhazzani W, Evans L, Alshamsi F, Moller MH, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Ng Gong M, Fan E, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines on the management of adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the ICU: first update. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(3):e219–34.

Li Bassi G, Suen JY, Dalton HJ, White N, Shrapnel S, Fanning JP, Liquet B, Hinton S, Vuorinen A, Booth G, et al. An appraisal of respiratory system compliance in mechanically ventilated covid-19 patients. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):199.

Cronin JN, Camporota L, Formenti F. Mechanical ventilation in COVID-19: a physiological perspective. Exp Physiol. 2021;107:683–93.

Camporota L, Cronin JN, Busana M, Gattinoni L, Formenti F. Pathophysiology of coronavirus-19 disease acute lung injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2022;28(1):9–16.

Chiumello D, Bonifazi M, Pozzi T, Formenti P, Papa GFS, Zuanetti G, Coppola S. Positive end-expiratory pressure in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: the heterogeneous effects. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):431.

Rossi S, Palumbo MM, Sverzellati N, Busana M, Malchiodi L, Bresciani P, Ceccarelli P, Sani E, Romitti F, Bonifazi M, et al. Mechanisms of oxygenation responses to proning and recruitment in COVID-19 pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(1):56–66.

Gibot S, Conrad M, Courte G, Cravoisy A. Positive end-expiratory pressure setting in COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome: comparison between electrical impedance tomography, PEEP/FiO2 tables, and transpulmonary pressure. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:720920.

van der Zee P, Somhorst P, Endeman H, Gommers D. Electrical impedance tomography for positive end-expiratory pressure titration in COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):280–4.

Stevic N, Chatelain E, Dargent A, Argaud L, Cour M, Guerin C. Lung recruitability evaluated by recruitment-to-inflation ratio and lung ultrasound in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(8):1025–7.

Tusman G, Wallin M, Acosta C, Santanera B, Portela F, Viotti F, Fuentes N, Hallback M, Suarez-Sipmann F. Positive end-expiratory pressure individualization guided by continuous end-expiratory lung volume monitoring during laparoscopic surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-021-00800-2.

Suarez-Sipmann F, Tusman G, Wallin M. Continuous non-invasive monitoring of cardiac output and lung volume based on CO2 kinetics. In: Vincent J-L, editor. Annual update in intensive care and emergency medicine. Berlin: Springer; 2019. p. 215–29.

Sigmundsson TS, Ohman T, Hallback M, Suarez-Sipmann F, Wallin M, Oldner A, Hallsjo-Sander C, Bjorne H. Comparison between capnodynamic and thermodilution method for cardiac output monitoring during major abdominal surgery: an observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38(12):1242–52.

Ohman T, Sigmundsson TS, Hallback M, Suarez Sipmann F, Wallin M, Oldner A, Bjorne H, Hallsjo Sander C. Clinical and experimental validation of a capnodynamic method for end-expiratory lung volume assessment. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020;64(5):670–6.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Tusman G, Acosta CM, Wallin M, Hallback M, Esperatti M, Peralta G, Gonzalez ME, Suarez-Sipmann F. Perioperative continuous noninvasive cardiac output monitoring in cardiac surgery patients by a novel capnodynamic method. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36:2900–7.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome N, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–8.

Enghoff H. Volumen inefficax, Bemerkungen zur Frage des schadlichen Raumes. Upsala Lakareforen Forh. 1938;44:191–218.

Chen L, Del Sorbo L, Grieco DL, Junhasavasdikul D, Rittayamai N, Soliman I, Sklar MC, Rauseo M, Ferguson ND, Fan E, et al. Potential for lung recruitment estimated by the recruitment-to-inflation ratio in acute respiratory distress syndrome. A clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(2):178–87.

Tusman G, Sipmann FS, Borges JB, Hedenstierna G, Bohm SH. Validation of Bohr dead space measured by volumetric capnography. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(5):870–4.

Langer T, Brioni M, Guzzardella A, Carlesso E, Cabrini L, Castelli G, Dalla Corte F, De Robertis E, Favarato M, Forastieri A, et al. Prone position in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: a multi-centric study of more than 1000 patients. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):128.

Smit MR, Beenen LFM, Valk CMA, de Boer MM, Scheerder MJ, Annema JT, Paulus F, Horn J, Vlaar APJ, Kooij FO, et al. Assessment of lung reaeration at 2 levels of positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with early and late COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thorac Imaging. 2021;36(5):286–93.

Beloncle FM, Pavlovsky B, Desprez C, Fage N, Olivier PY, Asfar P, Richard JC, Mercat A. Recruitability and effect of PEEP in SARS-Cov-2-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):55.

Protti A, Santini A, Pennati F, Chiurazzi C, Cressoni M, Ferrari M, Iapichino GE, Carenzo L, Lanza E, Picardo G, et al. Lung response to a higher positive end-expiratory pressure in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Chest. 2021;161:979–88.

Chiumello D, Cressoni M, Chierichetti M, Tallarini F, Botticelli M, Berto V, Mietto C, Gattinoni L. Nitrogen washout/washin, helium dilution and computed tomography in the assessment of end expiratory lung volume. Crit Care. 2008;12(6):R150.

Caravita S, Baratto C, Di Marco F, Calabrese A, Balestrieri G, Russo F, Faini A, Soranna D, Perego GB, Badano LP, et al. Haemodynamic characteristics of COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring mechanical ventilation. An invasive assessment using right heart catheterization. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(12):2228–37.

Becker A, Seiler F, Muellenbach RM, Danziger G, Kamphorst M, Lotz C, Group PAS, Bals R, Lepper PM. Pulmonary hemodynamics and ventilation in patients with COVID-19-related respiratory failure and ARDS. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36(6):655–63.

Dell’Anna AM, Carelli S, Cicetti M, Stella C, Bongiovanni F, Natalini D, Tanzarella ES, De Santis P, Bocci MG, De Pascale G, et al. Hemodynamic response to positive end-expiratory pressure and prone position in COVID-19 ARDS. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2022;298:103844.

Hallsjo Sander C, Lonnqvist PA, Hallback M, Sipmann FS, Wallin M, Oldner A, Bjorne H. Capnodynamic assessment of effective lung volume during cardiac output manipulations in a porcine model. J Clin Monit Comput. 2016;30(6):761–9.

Suarez-Sipmann F, Villar J, Ferrando C, Sanchez-Giralt JA, Tusman G. Monitoring expired CO2 kinetics to individualize lung-protective ventilation in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Front Physiol. 2021;12:785014.

Zerbib Y, Lambour A, Maizel J, Kontar L, De Cagny B, Soupison T, Bradier T, Slama M, Brault C. Respiratory effects of lung recruitment maneuvers depend on the recruitment-to-inflation ratio in patients with COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):12.

Pan C, Chen L, Lu C, Zhang W, Xia JA, Sklar MC, Du B, Brochard L, Qiu H. Lung Recruitability in COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a single-center observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1294–7.

Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Busana M, Romitti F, Brazzi L, Camporota L. COVID-19 pneumonia: Different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1099–102.

Grasselli G, Tonetti T, Protti A, Langer T, Girardis M, Bellani G, Laffey J, Carrafiello G, Carsana L, Rizzuto C, et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(12):1201–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the patients who participated in the study and their families. The support of the Liverpool ICU staff during the conduct of this study is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

Liverpool ICU has received an unrestricted grant from Maquet Critical Care AB to support studies on mechanical ventilation. Maquet Critical Care AB had no influence on the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation nor the manuscript preparation and the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LF, AA, MH and MW contributed to study conception and design. LF, AS, WO, PM, DA and AA screened, recruited and managed the patients and AA performed the study procedures. Data analyses were performed by LF and AA. All authors participated in data interpretation and writing of the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/ETH00778) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05082168). The patients’ person responsible provided verbal consent to participate in the study as per the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research by the Australian National Health and Research Council (updated 2018).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MH is a current and MW is a former employee of Maquet Critical Care AB. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest do declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

STROBE checklist and ECMO cases.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schulz, L., Stewart, A., O’Regan, W. et al. Capnodynamic monitoring of lung volume and blood flow in response to increased positive end-expiratory pressure in moderate to severe COVID-19 pneumonia: an observational study. Crit Care 26, 232 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04110-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04110-0