Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused unprecedented pressure on healthcare system globally. Lack of high-quality evidence on the respiratory management of COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure (C-ARF) has resulted in wide variation in clinical practice.

Methods

Using a Delphi process, an international panel of 39 experts developed clinical practice statements on the respiratory management of C-ARF in areas where evidence is absent or limited. Agreement was defined as achieved when > 70% experts voted for a given option on the Likert scale statement or > 80% voted for a particular option in multiple-choice questions. Stability was assessed between the two concluding rounds for each statement, using the non-parametric Chi-square (χ2) test (p < 0·05 was considered as unstable).

Results

Agreement was achieved for 27 (73%) management strategies which were then used to develop expert clinical practice statements. Experts agreed that COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is clinically similar to other forms of ARDS. The Delphi process yielded strong suggestions for use of systemic corticosteroids for critical COVID-19; awake self-proning to improve oxygenation and high flow nasal oxygen to potentially reduce tracheal intubation; non-invasive ventilation for patients with mixed hypoxemic-hypercapnic respiratory failure; tracheal intubation for poor mentation, hemodynamic instability or severe hypoxemia; closed suction systems; lung protective ventilation; prone ventilation (for 16–24 h per day) to improve oxygenation; neuromuscular blocking agents for patient-ventilator dyssynchrony; avoiding delay in extubation for the risk of reintubation; and similar timing of tracheostomy as in non-COVID-19 patients. There was no agreement on positive end expiratory pressure titration or the choice of personal protective equipment.

Conclusion

Using a Delphi method, an agreement among experts was reached for 27 statements from which 20 expert clinical practice statements were derived on the respiratory management of C-ARF, addressing important decisions for patient management in areas where evidence is either absent or limited.

Trial registration: The study was registered with Clinical trials.gov Identifier: NCT04534569.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has emerged as a pandemic, resulting in unprecedented pressure on healthcare systems globally. Although most patients present with mild symptoms including fever and malaise, 8–32% of patients presenting to hospital may require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) [1,2,3], depending on the admission criteria and available resources, with an ICU mortality of 34–50% [3, 4].

Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) acute respiratory failure (C-ARF) who are admitted to the ICU with hypoxaemia typically require some form of respiratory support [5]. COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may differ from other causes of ARDS, since patients may present with profound hypoxaemia accompanied by a wide range of respiratory compliance [6,7,8]. However, whether ARDS due to COVID-19 is clinically similar to other forms of ARDS remains a matter of debate [7, 9,10,11]. Consequently, there is no uniform agreement on the optimal management of respiratory failure, including the most appropriate oxygenation and ventilation strategies that limit or prevent additional lung injury or other complications in these patients.

There are few published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) related to the respiratory management of C-ARF. As a result, clinical practice variations in the management of C-ARF exist, making the optimal therapeutic management unclear [12]. Given the dearth of evidence, we aimed to achieve agreement on the respiratory management of C-ARF using a Delphi process, defined by at least 70% agreement among experts who met pre-specified qualification criteria.

Methods

Delphi process

A steering committee of 10 critical care physicians actively involved in the management of patients with C-ARF was formed in August 2020. A Delphi process was used to generate agreement on the respiratory management of C-ARF [13, 14]. The study was registered with Clinical trials.gov Identifier: NCT04534569.

The steering committee recruited and convened an international group of intensivists with expertise in the field of acute respiratory failure. E-mail invitations were sent to 60 global experts to participate in the Delphi process. Upon acceptance, experts were included in the Delphi process to generate agreement. Surveys disseminated to the experts were prepared using Google Forms. The steering committee members did not participate in the Delphi process.

The overall scope of the project was determined through a search and review of available literature on C-ARF, published between 1st January and 3rd September 2020 by the steering committee (Additional file 1). A list of interventions for the respiratory management of C-ARF was prepared in areas where the committee felt clear evidence was lacking. The list was presented to experts in the form of a survey questionnaire, which included five sections: non-invasive respiratory interventions; invasive mechanical ventilation; refractory hypoxaemia; infection control; weaning and tracheostomy. The experts subsequently responded to several rounds of survey questionnaires conducted using an iterative approach using the Delphi method, to prioritise topics for inclusion, which were repeated until agreement and stability were achieved. Complete details of the Delphi process are given in Additional file 2.

Agreement and stability

For statements with responses on an ordinal 7–point Likert scale, ‘agreement’ was defined as a score of 5–7, ‘neutral’ by a score of 4 and ‘disagreement’ by a score of 1–3. Agreement was defined as achieved when > 70% experts voted for a given option on the Likert scale for a statement [13, 14]. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe the central tendency and dispersion of responses. For multiple-choice questions (MCQs), agreement was defined as achieved if > 80% experts voted for a particular option. Stability in the responses was assessed from round three onwards. Stability was assessed between the two concluding rounds for each statement, using the non-parametric Chi-square (χ2) test. p < 0·05 was considered as a significant variation or unstable. Data from the last stable questionnaire round of the Delphi process for each statement were included for preparing the final clinical statements.

Expert clinical practice statements

Expert clinical practice statements were derived by the steering committee from the clinical statements that generated agreements through the Delphi process. The expert clinical practice statements were considered to be “strong statements” when a median of ≥ 6 or ≤ 2 on the Likert scale or > 90% votes for any MCQ option were achieved [14]. For the expert clinical practice statements, the term “should” was used for the strong statements and “may” was used for the other statements.

The final results of this survey and the expert clinical practice statements were circulated among the experts. The manuscript was circulated among the experts for editing and approval before it was submitted for publication.

Results

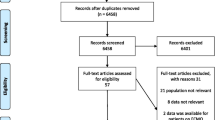

Of the 60 experts invited, 39 (65%) from 20 different countries and six continents participated in the Delphi process (Fig. 1); and 37 (95%) completed all rounds of the Delphi process. Median age of the experts was 53 (13) years and 5 (13%) were female. The majority (92%) were affiliated with university hospitals; and their median h-index was 33 (11–100).

Five survey questionnaire rounds were conducted between 4th September and 5th October 2020. Details of the Delphi rounds are provided in Fig. 2. The results of all 37 survey questionnaire statements used in the Delphi process are given in Table 1. At the end of the Delphi process, 27 statements (73%) achieved agreement and stability from which 20 expert clinical practice statements were prepared (Fig. 3). Reports of the first four survey rounds are provided in the online supplement (Additional file 3: Survey Report 1, Additional file 4: Survey Report 2, Additional file 5: Survey Report 3, and Additional file 6: Survey Report 4).

Expert clinical practice statements for the respiratory management of COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure. *Strong statement (a median of ≥ 6 or ≤ 2 on the Likert scale or > 90% votes for any MCQ option were achieved). HFNO: high flow nasal oxygen; NIV: non-invasive ventilation; NMBA: neuromuscular blocking agent; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; VV-ECMO: veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; PSV: pressure support ventilation; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; ICU: intensive care unit; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; C-ARF: COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure

Expert clinical practice statements

Our study rapidly conducted a survey of recognised international experts using the Delphi process, generating 27 statements with large agreement on the respiratory management of C-ARF. From these statements, 20 expert clinical practice statements were derived, addressing critical knowledge gaps in clinical management. The experts made a number of important and relevant recommendations specific to C-ARF covering invasive and non-invasive respiratory support, pharmacology, airway management, infrastructure and recovery.

The Delphi methodology is a well-recognized process to generate guidance based on consensus using collective intelligence [13, 14]. The expert clinical practice statements address important bedside decisions for patient management in areas where the current evidence is either absent or limited. These expert statements along with a discussion of the available literature are detailed below.

Is COVID-19-related ARDS similar to other forms of ARDS?

Expert statement

COVID-19-related ARDS is clinically similar to other forms of ARDS.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of COVID-19 involves SARS-CoV-2 invasion of host cells using angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor present in lungs and other organs. The viral invasion is followed by replication in type II alveolar pneumocytes that induces a dysregulated host immune response which in turn causes alveolar damage and ARDS [15]. Lung autopsy studies in patients who died from COVID-19 demonstrate diffuse alveolar damage along with significant endotheliitis and microthrombi in the pulmonary microvasculature [16,17,18]. Diffuse alveolar damage and alveolar haemorrhage with capillary damage are also noted in patients with non-COVID-19-related ARDS [18, 19]. In a cohort of 31 patients with COVID-19, higher lung compliance and volumes were found compared to patients with non-COVID-19 ARDS for a given PaO2/FiO2 [6, 8, 20]. This created the controversy that the pathophysiology of COVID-19-related ARDS is different from conventional ARDS [6, 7, 9,10,11]. Though there may be some differences in the pathophysiology of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 ARDS, the clinical presentation is similar [16,17,18]. The respiratory mechanics of ventilated patients with C-ARF were noted to be similar to classical ARDS in larger observational multicentre studies [21,22,23]. Further studies incorporating lung imaging and perfusion analysis will better address this important pathophysiological and clinical issue in future.

Corticosteroids

Expert statement

Systemic corticosteroids should be used in patients with critical COVID-19.

Dexamethasone is the preferred choice of systemic corticosteroids in patients of C-ARF.

The daily dose of dexamethasone should be 6 mg.

The preferred duration of systemic corticosteroids is 5–10 days.

Discussion

There is a strong suggestion for the use of systemic corticosteroids in critical COVID-19 [World Health Organisation (WHO) definition for COVID-19-ARDS, sepsis and septic shock] to reduce the need for invasive mechanical ventilation [24]. Experts preferred the use of dexamethasone at a dose of 6 mg daily for a duration of 5–10 days, as used in the RECOVERY trial over other corticosteroids, higher dose and longer duration [25]. The RECOVERY trial and subsequent trials on corticosteroids in COVID-19 found a mortality benefit with its use [25,26,27]. However, some questions remain unanswered, such as the type, duration of corticosteroid therapy, timing of initiation and role of a higher dose [28]. The results of ongoing trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04395105 and NCT04509973) will provide further information.

Awake self-proning

Expert statement

Awake self-proning may improve oxygenation when used in patients with C-ARF requiring supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation (SpO2) > 90%.

Discussion

Use of early prone position in patients with severe ARDS on invasive mechanical ventilation has been shown to significantly reduce mortality [28]. Though small observational studies in non-COVID-19 [29] and COVID-19 [30, 31] patients have reported improvements in oxygenation with awake self-proning, its impact on reducing tracheal intubation or mortality is unknown. Studies have shown either conflicting results or are difficult to interpret, as awake self-proning was used in combination with other non-invasive respiratory support [29,30,31]. In addition, there is a concern about delaying intubation in patients in whom awake self-proning is used [32]. Ongoing RCTs on awake self-proning in C-ARF (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04395144, NCT04347941, NCT04350723) may provide further guidance.

High Flow Nasal Oxygen (HFNO)

Expert statement

HFNO therapy should be considered as an alternative strategy for oxygen support.

HFNO should be used in patients who are unable to maintain SpO2 > 90% using oxygen delivery through a venturi mask or may be used in patients with increasing oxygen requirement.

HFNO may avoid the need for tracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with C-ARF.

Discussion

HFNO and non-invasive ventilation (NIV) [full-face mask or nasal mask delivering pressure support plus positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)] were initially avoided in patients with C-ARF due to the concern around infectious aerosol generation. However, limited availability of invasive ventilators and ICU beds, favourable experience in small studies and increasing availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) have led to increased use of non-invasive therapies [33,34,35]. Patients on non-invasive respiratory support need continuous monitoring to avoid any delays in tracheal intubation. A recent clinical practice guideline gave a strong recommendation for the use of HFNO over conventional oxygen therapy in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF) to prevent tracheal intubation [36]. Though there has been conflicting evidence regarding the use of HFNO to prevent invasive mechanical ventilation in C-ARF, experts recommended its use [37,38,39]. However, robust studies regarding the risk of aerosol dispersion, optimal settings, comparison with other non-invasive respiratory supports and outcomes are lacking in C-ARF patients.

Non-invasive ventilation and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

Expert statement

NIV should be considered in patients with mixed respiratory failure (hypercapnia and hypoxemia) and may be used in patients with increased work of breathing which is observed subjectively.

Discussion

NIV failure and higher ICU mortality were observed in patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS in a sub-analysis of the LUNG SAFE study including 2813 non-COVID patients receiving NIV [40]. There are inconclusive data regarding the role of NIV in reducing the need for invasive mechanical ventilation or mortality in C-ARF patients, from small retrospective studies [41, 42]. CPAP was used in small retrospective studies with some benefit in reducing tracheal intubation in mild-to-moderate COVID-19-related ARDS [43, 44]. Helmet CPAP is also used for management of C-ARF and recommended over HFNO to limit the exposure of healthcare workers (HCW) to aerosols [45]. However, the evidence on effectiveness of helmet CPAP in C-ARF in reducing the need of tracheal intubation is conflicting [46, 47]. In addition, the helmet interface may not be universally available. Future trials comparing HFNO with helmet CPAP may settle this debate. (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04395807).

Tracheal intubation

Expert statement

The appropriate triggers for tracheal intubation include altered mental status, hemodynamic instability and failure to maintain SpO2 > 90% with non-invasive respiratory interventions.

Discussion

The decision for tracheal intubation in patients receiving non-invasive respiratory support is challenging, requiring a fine balance between early intubation and risks of invasive mechanical ventilation versus the adverse effects of delaying intubation. The impact of early versus delayed tracheal intubation has not been compared in patients with C-ARF. The decision for tracheal intubation in COVID-19 patients may be best determined using a combination of factors that include clinical acumen, oxygen saturation, dyspnoea and respiratory rate [48, 49]. Experts recommended the use of clinical criteria to be preferred over the use of arterial blood gas or imaging findings to determine the need for tracheal intubation.

Lung protective ventilation

Expert statement

Lung protective ventilation (LPV) should be used for patients with C-ARF on IMV.

The targets for LPV in C-ARF include tidal volume of 4–6 ml/kg of predicted body weight, plateau pressure ≤ 30 cm of H2O and driving pressure ≤ 15 cm of H2O.

Discussion

Experts agreed that the COVID-19-related ARDS is clinically similar to other forms of ARDS; hence, there was a full agreement for the use of lung protective ventilatory strategies (tidal volume 4–6 mL/kg of predicted body weight and plateau pressure ≤ 30 cm of H2O). Severe hypoxaemia with near normal respiratory system compliance, a combination rarely seen in ARDS, had been noted in small studies [6, 7]. However, in large observational multicentre studies, the respiratory mechanics of ventilated patients with COVID-19-related ARDS were noted to be similar to non-COVID-19 ARDS [20,21,22].

Recruitment manoeuvres

Expert statement

Recruitment manoeuvres may be considered only in selected patients with C-ARF on invasive mechanical ventilation, in view of their potential deleterious effects.

Discussion

Diffuse alveolar damage, endotheliitis and microthrombi in pulmonary microvasculature have been reported in small autopsy studies of COVID-19 patients [16,17,18]. Microthrombi causing hypoxaemia will not respond to PEEP or a recruitment manoeuvre. The experts suggested that recruitment manoeuvres, if ever used should be individualised, in view of the potential harmful effects as seen in non-COVID-19-related ARDS [50, 51].

Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA)

Expert statement

NMBA may be considered during the early phase of invasive mechanical ventilation in case of patient-ventilator dyssynchrony.

Discussion

Recent meta-analyses have not demonstrated unambiguous benefits on important patient outcomes with the use of NMBA in non-COVID ARDS [52, 53]. It is possible that the impact of NMBA infusion on mortality depends on the strategy used in the control arm. The strong suggestion in favour of the use of NMBA by our experts, in case of patient-ventilator dyssynchrony contrasts with this lack of certainty and may be supported by the relative safety demonstrated so far. Clinical experience from around the world over the last year has demonstrated that it can be difficult to ventilate these patients in the very acute phase without NMBA, thus the apparent discordance between the recommendation of the experts and the literature in non-COVID-19 patients. However, recent guidelines recommend the use of an NMBA infusion for 48 h in patients with refractory hypoxemia despite deep sedation to facilitate lung protective ventilation strategy or prone positioning and/or when there is high respiratory drive despite optimal sedation [54, 55]. There are no published trials evaluating the use of NMBA on outcomes of ventilated patients with C-ARF.

Prone ventilation

Expert statement

Prone position in patients with C-ARF on invasive mechanical ventilation should be used for a duration of 16–24 h per session to improve oxygenation.

Discussion

Prone position for ventilated patients with C-ARF was strongly suggested by experts, for a duration of 16–24 h per session, similar to the indication in non-COVID-19-related ARDS [28, 53, 56].

Veno-Venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (V-V ECMO)

Expert statement

V-V ECMO may be considered in patients with refractory hypoxemia on invasive mechanical ventilation, who do not respond to other adjuvant therapies.

Discussion

These recommendations are in agreement with the WHO and extracorporeal life support organisation (ELSO) guidelines for the management of COVID-19 [24, 57]. Though higher mortality was reported during initial days of the pandemic, there is increasing experience and evolving evidence showing favourable outcomes with ECMO in COVID-19 patients [58,59,60]. In a recent meta-analysis, the 90-day mortality was lower in non-COVID-19-related ARDS patients on ECMO as compared to conventional ventilation [61]. In the EOLIA trial, the greatest benefit of V-V ECMO was seen in patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS or severe respiratory acidosis after optimisation of ventilator settings [62]. Experts recommend V-V ECMO for patients with refractory hypoxemia when lung protective ventilation and prone ventilation have failed or the latter is contraindicated.

Infection control

Expert statement

Bag mask ventilation, HFNO, NIV, tracheal intubation, open suctioning, bronchoscopy, tracheal extubation and tracheostomy may be considered as aerosol-generating procedures in and outside the ICU.

Airborne infection isolation rooms and video laryngoscopes may be considered during tracheal intubation; a closed suction system should be considered to reduce cross-transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the ICU.

Discussion

There is limited evidence regarding aerosol-generating procedures, or the use of airborne infection isolation rooms, use of video laryngoscopes during tracheal intubation and closed suction systems to mitigate aerosol generation in COVID-19 patients [35, 63, 64]. Simulation studies on aerosol production during tracheal intubation and extubation have provided divergent results [65, 66]. There is conflicting evidence on aerosol generation with NIV or HFNO [35, 67, 68]. The experts have taken a conservative approach, labelling procedures as aerosol generating, until robust evidence is generated to the contrary.

Weaning from invasive mechanical ventilation

Expert statement

Weaning should not be delayed, for the threat of the risk of reintubation.

A pressure support ventilation trial for 30 min to 2 h may be preferred over other weaning strategies.

Discussion

Weaning and extubation (in particular the strategy of delaying weaning) are very relevant to COVID-19 patients, due to concerns of the increased risk of aerosol exposure to the healthcare worker, if there is failure of tracheal extubation and need for a reintubation. In addition, there are concerns of aerosol generation with the use of the open T-piece as compared to pressure support ventilation. Nevertheless, the experts were strongly against delaying extubation in order to potentially reduce risks of later reintubation, suggesting the use of similar criteria as in non-COVID-19 patients [69]. The recommendation regarding the weaning strategy is consistent with recent evidence supporting pressure support ventilation for 30 min over T-piece for two hours, although this is not universally accepted [70, 71].

Early mobilisation

Expert statement

Early mobilization may be beneficial in patients on respiratory support for C-ARF.

Discussion

Experts suggested that early mobilisation may be beneficial in patients with C-ARF receiving respiratory support; given the evidence that early mobilisation of ICU patients has significant benefits [72].

Tracheostomy

Expert statement

The timing of tracheostomy to facilitate weaning from mechanical ventilation should be the same as in non-COVID-19 patients.

Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) with or without guidance (using ultrasound or bronchoscopic) may be preferred over other techniques.

Discussion

The timing and technique of tracheostomy, due to possible aerosol generation or dispersion, have generated intense debate among clinicians [73]. The safe period for performing a tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients is recommended to be 10–21 days after tracheal intubation to reduce infectious risk. [73]. However, no increased risk of infection to healthcare workers was observed, when clinical judgment-based instead of fixed timing tracheostomy was performed with appropriate PPE use [72]. Modifications to tracheostomy techniques are recommended in COVID-19 patients to reduce aerosolisation risk [75]. Although surgical tracheostomy was recommended over PDT, based on experiences from the SARS epidemic, the use of PDT in COVID-19 patients has not shown any increased risk to healthcare workers till date [74].

Dissensus among the experts on the respiratory management of C-ARF

The following clinical statements did not achieve the desired agreement and stability despite several iterative Delphi rounds. This reflects existing areas of uncertainty.

There was no agreement among the experts that awake self-proning may prevent the need for invasive mechanical ventilation. Experts did not recommend the use of NIV in all patients with C-ARF as an alternative strategy for oxygen support or to avoid the need for invasive mechanical ventilation, unlike with HFNO. In addition, the experts did not agree that HFNO produces fewer aerosols as compared to NIV with face mask.

There was disagreement for the use of non-conventional modes of mechanical ventilation including airway pressure release ventilation and pressure-regulated volume control. There was no agreement for higher versus lower PEEP strategy, nor the method of PEEP selection in these patients. Lung hyperinflation has been reported in small case series of patients with C-ARF with the use of high PEEP [76, 77]. There was disagreement for the effectiveness of adjuvant therapies for refractory hypoxaemia (inhaled nitric oxide, nebulized prostacyclin, etc.). This likely reflects the lack of any demonstrable benefits with any of the salvage therapies, other than prone ventilation [56].

There was no agreement on any combination of PPE over the other. A Cochrane meta-analysis (24 studies with 2278 participants) on the role of PPE in preventing infections among healthcare workers concluded that there was no difference between various types of PPE [78]. There was no agreement on the beneficial effect of chest physiotherapy in patients with C-ARF. Questions related to specific chest physiotherapy interventions were not asked, which may be a limitation. A personalised approach may be required with some of these interventions, depending on the patient, phase of illness and the respiratory mechanics. The benefits of chest physiotherapy in ventilated patients with C-ARF are unclear, with limited evidence on the risks of aerosol dispersion of the virus with some of the therapeutic manoeuvres [79].

Strengths and limitations

Our work has several strengths. Firstly, our panel included a large number of global experts in the field of respiratory failure, with experience in the management of C-ARF and with diverse geographical representation. Secondly, anonymity of experts and their individual responses were preserved until completion, to avoid inherent bias during the Delphi process due to dominance and group pressure. Thirdly, we were able to successfully complete the process over five survey rounds, maintaining a tight timeline (one month) despite experts being busy during a pandemic, which was essential considering the rapidly evolving evidence. Fourthly, we were able to achieve agreement in 73% of our clinical statements.

Our work has limitations. It is difficult to answer 'yes' or 'no' to some questions, as a personalised approach may be required for some clinical interventions. It is also possible that the responses from the experts could have been influenced by the way they interpreted the statements. The feedback from the experts (allowed in all the rounds) and the stability of the responses should have ensured fidelity of the responses and minimised the risk of responder bias. Secondly, factors such as non-availability of or inadequate experience with some treatment modalities and variation in regional guidelines may have influenced the opinions of experts and affected the generation of statements. Thirdly, some aspects of respiratory management, such as extubation to NIV or HFNO to prevent re-intubation, were not included.

These expert clinical practice statements will provide guidance to the clinician at the bedside. However, several questions regarding the respiratory management of C-ARF remain unanswered and new evidence is being generated at a rapid rate. We have summarized these as future research priorities in Table 2.

Conclusions

Using a Delphi method, an agreement among experts was reached for 27 statements on the respiratory management of C-ARF, addressing important decisions for patient management in areas where evidence is either absent or limited. Strong evidence from high-quality clinical trials is needed to clarify the remaining uncertainties. While these expert clinical practice statements provide clinical direction with C-ARF, some of these general principles may help with the management of other viral pneumonias or future variants of the SARS-CoV-2 strain.

Availability of data and materials

Supporting data are available with the corresponding author.

References

Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, Hardwick HE, Pius R, Norman L, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985.

Kim L, Garg S, O'Halloran A, Whitaker M, Pham H, Anderson EJ, et al. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-hospital Mortality among Hospitalized Adults Identified through the U.S. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis. 2020: ciaa1012.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). COVID-19 Surveillance Report (Week 44, 2020). https://covid19-surveillance-report.ecdc.europa.eu Accessed 11 November 2020.

Armstrong RA, Kane AD, Cook TM. Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1340–9.

Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. 2020;323:1545–6.

Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Busana M, Romitti F, Brazzi L, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1099–102.

Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, Busana M, Rossi S, Chiumello D. COVID-19 does not lead to a “typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1299–300.

Gattinoni L, Meissner K, Marini JJ. The baby lung and the COVID-19 era. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1438–40.

Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. P-SILI is not justification for intubation of COVID-19 patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:105.

Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. Caution about early intubation and mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:78.

Fan E, Beitler JR, Brochard L, Calfee CS, Ferguson ND, Slutsky AS, et al. COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: is a different approach to management warranted? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:816–21.

Azoulay E, de Waele J, Ferrer R, Staudinger T, Borkowska M, Povoa P, et al. International variation in the management of severe COVID-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24:486.

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:401–9.

Taylor E. We Agree, Don’t We? The Delphi Method for Health Environments Research. HERD. 2020;13:11–23.

Mason RJ. Pathogenesis of COVID-19 from a cell biology perspective. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000607.

Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–8.

Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–8.

Barton LM, Duval EJ, Stroberg E, Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153:725–33.

Kumar R, Lee MH, Mickael C, Kassa B, Pasha Q, Tuder R, et al. Pathophysiology and potential future therapeutic targets using preclinical models of COVID-19. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6:00405–2020.

Chiumello D, Busana M, Coppola S, Romitti F, Formenti P, Bonifazi M, et al. Physiological and quantitative CT-scan characterization of COVID-19 and typical ARDS: a matched cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2187–96.

Grasselli G, Tonetti T, Protti A, Langer T, Girardis M, Bellani G, et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1201–8.

Ferrando C, Suarez-Sipmann F, Mellado-Artigas R, Hernández M, Gea A, Arruti E, et al. Clinical features, ventilatory management, and outcome of ARDS caused by COVID-19 are similar to other causes of ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2200–11.

Grieco DL, Bongiovanni F, Chen L, Menga LS, Cutuli SL, Pintaudi G, et al. Respiratory physiology of COVID-19-induced respiratory failure compared to ARDS of other etiologies. Crit Care. 2020;24:529.

WHO COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance COVID-19. Living guidance. Updated 25 January 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338882 Accessed 27 January 2021.

RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med Jul. 2020: NEJMoa2021436.

WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group, Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, Angus DC, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1–13.

Siemieniuk R, Rochwerg B, Agoritsas T, Lamontagne F, Leo YS, Macdonald H, et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370:m3379.

Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard J-C, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T, et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–68.

Ding L, Wang L, Ma W, He H. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:28.

Coppo A, Bellani G, Winterton D, Di Pierro M, Soria A, Faverio P, et al. Feasibility and physiological effects of prone positioning in non-intubated patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 (PRON-COVID): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:765–74.

Ferrando C, Mellado-Artigas R, Gea A, Arruti E, Aldecoa C, Adalia R, et al. Awake prone positioning does not reduce the risk of intubation in COVID-19 treated with high-flow nasal oxygen therapy: a multicenter, adjusted cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:597.

Padrão EMH, Valente FS, Besen BAMP, Rahhal H, Mesquita PS, de Alencar JCG, et al. Awake prone positioning in COVID-19 hypoxemic respiratory failure: exploratory findings in a single-center retrospective cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27:1249–59.

NHS England. Guidance for the role and use of non-invasive respiratory support in adult patients with COVID19 (confirmed or suspected) 6 April 2020, Version 3. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/specialty-guide-NIV-respiratory-support-and-coronavirus-v3.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2020.

Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:854–87.

Agarwal A, Basmaji J, Muttalib F, Granton D, Chaudhuri D, Chetan D, et al. High-flow nasal cannula for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19: systematic reviews of effectiveness and its risks of aerosolization, dispersion, and infection transmission. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:1217–48.

Rochwerg B, Einav S, Chaudhuri D, Mancebo J, Mauri T, Helviz Y, et al. The role for high flow nasal cannula as a respiratory support strategy in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2226–37.

Vianello A, Arcaro G, Molena B, Turato C, Sukthi A, Guarnieri G, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy to treat patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure consequent to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thorax. 2020;75:998–1000.

Xia J, Zhang Y, Ni L, Chen L, Zhou C, Gao C, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen in coronavirus disease 2019 patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a multicenter. Retrospective Cohort Study Crit Care Med. 2020;48:e1079–86.

Patel M, Gangemi A, Marron R, Chowdhury J, Yousef I, Zheng M, et al. Retrospective analysis of high flow nasal therapy in COVID-19-related moderate-to-severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2020;7:e000650.

Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Madotto F, Fan E, Brochard L, et al. Noninvasive ventilation of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome insights from the LUNG SAFE study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:67–77.

Belenguer-Muncharaz A, Hernández-Garcés H. Failure of non-invasive ventilation after use of high-flow oxygen therapy in patients with SARS-Coronavirus-2 pneumonia. Med Intensiva. 2020;S0210–5691(20):30220–5.

Mukhtar A, Lotfy A, Hasanin A, El-Hefnawy I, El Adawy A. Outcome of non-invasive ventilation in COVID-19 critically ill patients: a Retrospective observational Study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39:579–80.

Vitacca M, Nava S, Santus P, Harari S. Early consensus management for non-ICU acute respiratory failure SARS-CoV-2 emergency in Italy: from ward to trenches. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000632.

Pagano A, Porta G, Bosso G, Allegorico E, Serra C, Dello Vicario F, et al. Non-invasive CPAP in mild and moderate ARDS secondary to SARS-CoV-2. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2020;280:103489.

Ashish A, Unsworth A, Martindale J, Sundar R, Kavuri K, Sedda L, et al. CPAP management of COVID-19 respiratory failure: a first quantitative analysis from an inpatient service evaluation. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2020;7(1):e000692.

Aliberti S, Radovanovic D, Billi F, Sotgiu G, Costanzo M, Pilocane T, Saderi L, et al. Helmet CPAP treatment in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a multicentre cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001935.

Ashish A, Unsworth A, Martindale J, Sundar R, Kavuri K, Sedda L, et al. CPAP management of COVID-19 respiratory failure: a first quantitative analysis from an inpatient service evaluation. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2020;7:e000692.

Wei H, Jiang B, Behringer EC, Hofmeyr R, Myatra SN, Wong DT, et al. Controversies in airway management of COVID-19 patients: updated information and international expert consensus recommendations. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:361–6.

Tobin MJ. Basing respiratory management of COVID-19 on physiological principles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1319–20.

Pensier J, de Jong A, Hajjej Z, Molinari N, Carr J, Belafia F, et al. Effect of lung recruitment maneuver on oxygenation, physiological parameters and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1691–702.

Papazian L, Aubron C, Brochard L, Chiche JD, Combes A, Dreyfuss D, et al. Formal guidelines: management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:69.

Ho ATN, Patolia S, Guervilly C. Neuromuscular blockade in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:12.

Tarazan N, Alshehri M, Sharif S, Al Duhailib Z, Møller MH, Belley-Cote E, et al. Neuromuscular blocking agents in acute respiratory distress syndrome: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2020;8:61.

Hraiech S, Yoshida T, Annane D, Duggal A, Fanelli V, Gacouin A, et al. Myorelaxants in ARDS patients. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2357–72.

Alhazzani W, Belley-Cote E, Møller MH, Angus DC, Papazian L, Arabi YM, et al. Neuromuscular blockade in patients with ARDS: a rapid practice guideline. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1977–86.

Cherian SV, Kumar A, Akasapu K, Ashton RW, Aparnath M, Malhotra A. Salvage therapies for refractory hypoxemia in ARDS. Respir Med. 2018;141:150–8.

ELSO. COVID-19 registry dashboard. https://www.elso.org/Registry/FullCOVID19RegistryDashboard.aspx. Accessed 9 October 2020.

Lorusso R, Combes A, Coco VL, De Piero ME, Belohlavek J. ECMO for COVID-19 patients in Europe and Israel. Intensive Care Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06272-3.

Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, Iwashyna TJ, Slutsky AS, Fan E, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet. 2020;396:1071–8.

Schmidt M, Hajage D, Lebreton G, Monsel A, Voiriot G, Levy D, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1121–31.

Combes A, Peek GJ, Hajage D, Hardy P, Abrams D, Schmidt M, et al. ECMO for severe ARDS: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2048–57.

Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, Demoule A, Lavoué S, Guervilly C, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965–75.

De Jong A, Pardo E, Rolle A, Bodin-Lario S, Pouzeratte Y, Jaber S. Airway management for COVID-19: a move towards universal videolaryngoscope? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:555.

Ahn JY, An S, Sohn Y, Cho Y, Hyun JH, Baek YJ, et al. Environmental contamination in the isolation rooms of COVID-19 patients with severe pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen therapy. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:570–6.

Brown J, Gregson FKA, Shrimpton A, Cook TM, Bzdek BR, Reid JP, et al. A quantitative evaluation of aerosol generation during tracheal intubation and extubation. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:174–81.

Ward JD, Phan TD, Nguyen LV, Wynne DD, Scott DA, Clinical Aerosolisation Study Group. Aerosolisation during tracheal intubation and extubation in an operating theatre setting. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:182–8.

Haymet A, Bassi GL, Fraser JF. Airborne spread of SARS-CoV-2 while using high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy: myth or reality? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2248–51.

Hui DS, Chow BK, Lo T, Sang OTY, Ko FW, Ng SS, et al. Exhaled air dispersion during high-flow nasal cannula therapy versus CPAP via different masks. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1802339.

Fan E, Zakhary B, Amaral A, McCannon J, Girard TD, Morris PE, et al. Liberation from mechanical ventilation in critically ill adults. An official ATS/ACCP clinical practice guideline. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:441–3.

Subirà C, Hernández G, Vázquez A, Rodríguez-García R, González-Castro A, García C, et al. Effect of pressure support vs T-piece ventilation strategies during spontaneous breathing trials on successful extubation among patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2175–82.

Goligher EC, Detsky ME, Sklar MC, Campbell VT, Greco P, Amaral ACKB, et al. Rethinking inspiratory pressure augmentation in spontaneous breathing trials. Chest. 2017;151:1399–400.

Tipping CJ, Harrold M, Holland A, Romero L, Nisbet T, Hodgson CL. The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:171–83.

McGrath BA, Brenner MJ, Warrillow SJ, Pandian V, Arora A, Cameron TS, et al. Tracheostomy in the COVID-19 era: global and multidisciplinary guidance. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:717–25.

McGrath BA, Brenner MJ, Warrillow SJ. Tracheostomy for COVID-19: business as usual? Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:867–71.

Avilés-Jurado FX, Prieto-Alhambra D, González-Sánchez N, de Ossó J, Arancibia C, Rojas-Lechuga MJ, Ruiz-Sevilla L, et al. Timing, complications, and safety of tracheotomy in critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;147:1–8.

Roesthuis L, van den Berg M, van der Hoeven H. Advanced respiratory monitoring in COVID-19 patients: use less PEEP! Crit Care. 2020;24:230.

Schultz MJ. High versus low PEEP in non-recruitable collapsed lung tissue: possible implications for patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e44.

Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, Tikka C, Ruotsalainen JH, Edmond MB, et al. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD011621.

Lazzeri M, Lanza A, Bellini R, Bellofiore A, Cecchetto S, Colombo A, et al. Respiratory physiotherapy in patients with COVID-19 infection in acute setting: a Position Paper of the Italian Association of Respiratory Physiotherapists (ARIR). Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.4081/monaldi.2020.1285.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The steering committee included PN, SNM, RJ EA, AKK, SG, YJ, DJ, PR and KS. SNM served as moderator of the working group. PN, SNM and RJ contributed to conception and design of the work, data acquisition, data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. EA, AKK, SG, YJ, DJ, PR and KS contributed to design of the work, data acquisition, data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. PN and RJ did the literature search and data analysis, PN and SNM prepared the figures. The members of the steering committee did not respond to the survey questionnaires. The experts included were WA, MA, YMA, JB, LJB, AMD, BD, SE, AE, OG, SMG, CG, SJ, GCK, YK, JBL, FRM, MLNGM, JM, AM, MTM, BAM, SM, AM, MM, MN, PKP, PP, JVP, JP, DVP, LP, PS, MJS, MSH, SS, MS, RT, AAU and TW. The experts completed the survey questionnaire in the various rounds of the Delphi process; the result of which was used to draft the expert clinical practice statements. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval is not applicable for this study. Consent to participate in the study was taken from all experts.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was taken from all co-authors.

Competing interests

EA reports having taken professional fees for lectures from Gilead, Pfizer, Baxter and Alexion. His research group has been supported by Ablynx, Fisher & Paykel, Jazz Pharma and MSD, all outside the scope of submitted work. AKK reports institutional funding for 2 trials, a randomized Clinical Trial of CLR2.0 Hemofiltration Treatment (C2Rx) in Severe or Critically Ill Adults With COVID-19 Infection (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04537975) and Blood Volume Assessment in COVID-19 ICU Patients—BVAC19 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04517695). He is site PI for SCCM Discovery Network Viral Infection and Respiratory Illness Universal Study [VIRUS]: COVID-19 Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04323787) and is a member of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) COVID-19 task force. AKK is a key opinion leader and consults for Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Philips North America and Zoll Medical, is on the advisory board for Potrero Medical and Retia Medical and receives compensation for his position for the chair of the trial steering committee for the SILtuximab in Viral ARds (SILVAR) Study (SILVAR) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04616586) all outside the scope of the submitted work. He is also funded with a Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) NIH/NCTAS KL2 TR001421 award for a trial on continuous postoperative hemodynamic and saturation monitoring. AKK is a founding member of BrainX LLC, a collaborative platform for research and development of artificial intelligence technology in critical care and perioperative medicine. YJ is a member of CII Medical Task Force, India and a member of the steering committee for a Phase 3, Prospective, Randomized, Open Label, Comparative, Clinical Study To Evaluate Efficacy And Safety Of Ulinastatin Plus Standard-Of-Care Compared To Standard-Of-Care In Treatment Of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) In Hospitalized COVID-19 Infection Patients. WAH is a co-chair of COVID-19 surviving sepsis campaign guidelines. MA is a panel member of Surviving Sepsis Campaign. YMA is a co-investigator on COVI-PRONE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04350723) and is a panel member of Surviving Sepsis Campaign CPG. LJB reports grants from Medtronic Covidien, grants and non-financial support from Fisher Paykel, non-financial support from Air Liquide, Sentec, Philips and General Electric (patent), all outside the scope of submitted work. SJ reports receiving consulting fees from Drager, Medtronic, Baxter, Fresenius and Fisher & Paykel, all outside the scope of submitted work. JBL received lectures fees from BD and Zoll (outside the scope: cooling devices), all outside the scope of submitted work. MLNGM is a co-founder, past-President and current Treasurer of WSACS (The Abdominal Compartment Society, http://www.wsacs.org). MLNGM is member of the medical advisory Board of Pulsion Medical Systems (part of Getinge group) and Serenno Medical, consults for Baxter, BD, BBraun, ConvaTec, Acelity, Spiegelberg and Holtech Medical and is co-founder of the International Fluid Academy (IFA) which is integrated within the not-for-profit charitable organization iMERiT (International Medical Education and Research Initiative) under the Belgian law, all outside the scope of submitted work. JM reports personal fees (last three years) from Faron, Medtronic and Janssen, all outside the scope of submitted work. AM reports grants from Fischer Paykel, Baxter and Ferring, and personal fees from Air Liquide, Amomed and Addmedica, all outside the scope of submitted work. MN is an advisor with Avant-Grande Health Inc and receive stock option for this role, all outside the submitted work. PKP reports grant funding from NIH for Operation Warp Speed COVID clinical trials and from DoD, Eli Lilly, Bristol Myers Squibb, ATOX Bio, Marcus Foundation, all outside the scope of submitted work. She is a council member of Society of Critical Care Medicine. LP reports lectures fees from Hamilton and Getinge and consultant fees from Löwenstein, all outside the scope of submitted work. MSH reports funding and support by the National Institute for Health Research Clinician Scientist Award (CS-2016–16-011). Also, the views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. MS reports paid consultancy, lecture grants: Teleflex Medical (Athlone, Ireland); Verathon Medical (Bothell, USA); travel grants, lecture grants: MSD Italy, MSD USA; Baxter Italy, all outside the scope of submitted work. AAU reports membership of Management Committee, SPRINT-SARI Australia. TW reports research Grants from DFG, BMBF, EU, WHO, fees for lectures from AstraZeneca, Basilea, Biotest, Bayer, Boehringer, GSK, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, all outside the scope of submitted work. He is a member on advisory Board of AstraZeneca, Basilea, Biotest, Bayer, Boehringer, GSK, Janssens, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Aventis. SNM reports membership of COVID-19 Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) guidelines committee and being on the steering committee of the COVID Steroid 2 Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04509973) and the HydrOxychloroquine Prophylaxis Evaluation (HOPE) Trial (CTRI registration No. CTRI/2020/05/025067). All other authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria.

Additional file 2.

Details and Results of the Delphi process.

Additional file 3.

Survey Report 1.

Additional file 4.

Survey Report 2.

Additional file 5.

Survey Report 3.

Additional file 6.

Survey Report 4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nasa, P., Azoulay, E., Khanna, A.K. et al. Expert consensus statements for the management of COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure using a Delphi method. Crit Care 25, 106 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03491-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03491-y