Abstract

Background

Sufentanil is commonly used for analgesia and sedation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Both ECMO and the pathophysiological changes derived from critical illness have significant effects on the pharmacokinetics (PK) of drugs, yet reports of ECMO and sufentanil PK are scarce. Here, we aimed to develop a population PK model of sufentanil in ECMO patients and to suggest dosing recommendations.

Methods

This prospective cohort PK study included 20 patients who received sufentanil during venoarterial ECMO (VA-ECMO). Blood samples were collected for 96 h during infusion and 72 h after cessation of sufentanil. A population PK model was developed using nonlinear mixed effects modelling. Monte Carlo simulations were performed using the final PK parameters with two typical doses.

Results

A two-compartment model best described the PK of sufentanil. In our final model, increased volume of distribution and decreased values for clearance were reported compared with previous PK data from non-ECMO patients. Covariate analysis showed that body temperature and total plasma protein level correlated positively with systemic clearance (CL) and peripheral volume of distribution (V2), respectively, and improved the model. The parameter estimates of the final model were as follows: CL = 37.8 × EXP (0.207 × (temperature − 36.9)) L h−1, central volume of distribution (V1) = 229 L, V2 = 1640 × (total plasma protein/4.5)2.46 L, and intercompartmental clearance (Q) = 41 L h−1. Based on Monte Carlo simulation results, an infusion of 17.5 μg h−1 seems to reach target sufentanil concentration (0.3–0.6 μg L−1) in most ECMO patients except hypothermic patients (33 °C). In hypothermic patients, over-sedation, which could induce respiratory depression, needs to be monitored especially when their total plasma protein level is low.

Conclusions

This is the first report on a population PK model of sufentanil in ECMO patients. Our results suggest that close monitoring of the body temperature and total plasma protein level is crucial in ECMO patients who receive sufentanil to provide effective analgesia and sedation and promote recovery.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT02581280, December 1st, 2014.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) is a temporary mechanical circulatory support for patients with cardiac failure [1, 2]. Because ECMO is invasive, analgesia and sedation are important to limit responsiveness, prevent accidental decannulation, and maintain ECMO flows, all of which promote recovery [3,4,5]. The use of opioids is standard practice during ECMO [6,7,8].

Sufentanil is a synthetic opioid drug, which has a rapid onset and is 5–10 times more potent than fentanyl [9]. It is highly protein bound (91–93%) [10], metabolised by the liver, and excreted as metabolites in the urine (2% unchanged, 80% metabolites) [11]. A large variability in sufentanil pharmacokinetics (PK) is expected in ECMO patients due to the combination of ECMO, drug characteristics, and disease factors [12]. Volume of distribution (Vd) is altered owing to physiologic changes related to critical illness, hemodilution, and sequestration in ECMO circuit, while clearance (CL) is variable owing to organ dysfunction and non-pulsatile flow in VA-ECMO [13,14,15]. ECMO could act as a reservoir that prolongs the effect of sedatives even after the drugs have been discontinued [16]. Despite the widespread use of ECMO, the literature regarding sufentanil PK and ECMO was based on only in vitro analysis, which showed 83% loss of sufentanil in ECMO circuits at 24 h [17]. In the present study, we aimed to develop a population PK model of sufentanil in ECMO patients and identify covariates associated with sufentanil exposure in order to suggest a more rational dosing recommendation.

Methods

Study design and ethics approval

This was a prospective, cohort study conducted at the cardiac intensive care unit in Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital in Seoul, Republic of Korea, between January 2016 and June 2017. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No.: 4-2014-0919) of Severance Hospital and was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02581280). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or the legal surrogates of unconscious patients. This study complied with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).

Study population

Twenty patients aged 19 years or older, who received sufentanil-based analgesia and sedation during VA-ECMO, were enrolled in this study. The exclusion criteria were younger than 19 years, known allergy to sufentanil, and taking any medication that could cause potential drug-drug interactions or alter sufentanil concentrations.

Dosing, administration, and data collection

ECMO patients received sufentanil for maintenance of analgesia and sedation supplemented as needed with midazolam. Sufentanil dosing in our centre was based on patients’ body weight, with initial infusion doses of 12.5 (< 60 kg) or 17.5 μg h−1 (≥60 kg). An initial bolus of 3 (< 60 kg) or 5 mg (≥ 60 kg) midazolam was given, with an initial infusion dose of 4.5 mg h−1. Management of pain should be guided by routine pain assessment of Nonverbal Pain Scale. Nurses assessed the depth of sedation, indicating the prevalent Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) in their work shift. Analgesia and sedation protocol was to keep patients deeply sedated during the first few days of ECMO followed by intermediate or light sedation before ECMO discontinuation when possible. The infusion rates of sufentanil and midazolam were modified to achieve a target RASS score, and each dose adjustment was recorded.

Data on demographics, organ function, ECMO, vital signs, and drug dosing were collected from the electronic medical records.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

The ECMO circuit included a centrifugal blood pump with a pump controller (Capiox® SP-101, Terumo Inc., Tokyo, Japan), an air-oxygen mixer (Sechrist® Ind., Anaheim, CA, USA), and conduit tubing (Capiox® EBS Circuit with X coating, Terumo Inc.). The days on ECMO, ECMO flow rate, and ECMO pump speed were recorded.

Sample collection and plasma concentration assay

The study was initiated during the first 48 h of starting ECMO. Blood samples were collected after 3 and 12 h of infusion and then every 24 h until 96 h had elapsed. When infusion was discontinued for any reason, blood was sampled after 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 6, and 12 h, and then every 24 h until 72 h had elapsed. Each blood sample (2 mL) was drawn from an existing arterial line and collected in a tube containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid as an anticoagulant. The blood samples were centrifuged at 1500×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the plasma was immediately stored at − 80 °C until needed.

The plasma concentrations of sufentanil were analysed using a validated HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) coupled with a 4000 Qtrap liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer (ASICX, Concord, Ontario, Canada). The plasma samples were denatured with acetonitrile containing 0.5 μg mL−1 prazosin as an internal standard. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 150,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. HPLC was performed on a Kinetex C18 analytical column (4.6 × 50 mm; particle size 2.6 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) with a mobile phase consisting of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.055 mL min−1. The lower limit of quantification for sufentanil was 0.02 μg L−1. The assay was validated between 0.02 and 10 μg L−1 with inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation of < 15%.

Population PK model development

The population PK model was developed using a first-order conditional estimation method with an interaction (FOCE+I) algorithm in the nonlinear mixed effects modelling software NONMEM® version 7.4 (ICON Development, Ellicott City, MD, USA). Pirana® ver. 2.9.2 and Xpose® ver. 4.0 (http://xpose.sourceforge.net) in R® ver. 3.2.4 (http://www.r-project.org) were used to visualise and evaluate the models. One-, two-, and three-compartment models were evaluated as the structural PK models. Inter-individual variability (IIV) for the PK parameters was modelled assuming a log-normal distribution: θi = θPop × EXP(ηi), where θi is the individual value of the parameter θ in the ith individual, θPop is the population value of this parameter, and ηi is a random variable with mean zero and variance ωη2 [18]. Proportional models for residual variability was used: cij = cpij × (1 + εij) in which cij is the jth observed concentration of the ith individual, cpij is the corresponding predicted concentration, and εij is a random variable with mean zero and variance σ2.

The likelihood ratio test was used to evaluate statistical significance between nested models where a decrease in the objective function value (OFV), a statistical equivalent to the − 2 log likelihood of the model, of at least 3.84 was considered statistically significant for an added parameter (χ2 distribution, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, p < 0.05). In addition, bias of the goodness-of-fit plots (observed versus population predicted concentrations, observed versus individual predicted concentrations, conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus population predicted concentrations, and CWRES versus time after dosing), visual improvement of individual plots, confidence intervals of parameter estimates, and shrinkage were assessed. The aim of this study was to examine the potential effect of various covariates of the model structural parameters. The following covariates were investigated: sex, age, weight, lean body weight, body mass index, tympanic body temperature, total plasma protein, partial pressure of carbon dioxide, plasma pH, estimated glomerular filtration rate, serum creatinine, total bilirubin, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, use of continuous renal replacement therapy, ECMO pump speed, and ECMO flow rate. The estimated parameters were plotted against each covariate to identify its influence. Continuous covariates (Cov) were incorporated into the structural model with centering on their median values within the population and tested using power (1), linear (2), and exponential (3) equations:

where θTV is the typical value of the parameter and θCov quantifies the covariate effect. The covariate model building was carried out in a stepwise process. In the forward selection, a P value of < 0.05 was used (a decrease in OFV of at least 3.84, df = 1), while in the backward elimination, a P value of < 0.01 was applied (a decrease in the OFV of at least 6.64, df = 1).

Model evaluation and simulations

To evaluate stability in the final model, a non-stratified bootstrap analysis was performed using the PsN Toolkit [19]. A bootstrap with 5000 runs was performed on the final model to evaluate the internal validity of the parameter estimates and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The model performance was evaluated by means of prediction-corrected visual predictive checks (pc-VPCs). One thousand datasets were simulated from the final model, and the median and 90% CI of the simulated data were plotted along with the observed concentrations. To illustrate the effect of body temperature and total plasma protein level on predicted sufentanil concentrations, Monte Carlo simulations were performed using PK parameters from the final model. We assumed that sufentanil was continuously infused for 120 h with a rate of 12.5 or 17.5 μg h−1, which were the doses most frequently used in our ECMO patients. The median parameter values for the patient population were obtained with five different levels of body temperature (33, 35, 36.7, 38 and 39 °C) and four different total plasma protein levels (2, 4, 6, and 8 g dL−1) by simulating 1000 individuals in each case.

Results

Patients

Twenty ECMO patients were included, with a median age of 55 years, median weight of 69.4 kg, and median APACHE II score of 29 at the initiation of ECMO support. All the patients received mechanical ventilation and started ECMO during the first 12 h after the onset of myocardial infarction (MI). The median duration of VA-ECMO and sufentanil infusion was 138 and 110 h, respectively. Nine patients concurrently received continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) during ECMO (Table 1). Desired sedation level was reached or nearly reached (observed RASS = target RASS ± 1) in all patients. A population PK analysis was conducted with 106 plasma samples from the 20 patients. Concentration records that were below the lower limit of quantification were excluded from the analysis.

Population PK model building

A two-compartment model parameterised in terms of systemic clearance (CL), central volume of distribution (V1), peripheral volume of distribution (V2), and intercompartmental clearance (Q) was preferred to a one- and three-compartment model. Residual variability was described with a proportional residual error model. IIVs were included for CL and V2, since they significantly improved model performance. The structural model had an OFV of − 343.1. In the univariate covariate analysis, body temperature and total bilirubin were identified as significant covariates of CL, resulting in a drop in OFV of − 9.1 and − 6.0 points, respectively. In addition, total protein and lean body weight were significant covariate candidates of V2 with ∆ OFVs of − 9.3 and − 3.4 points, respectively. After the forward selection and backward elimination, total bilirubin for CL and lean body weight for V2 were removed.

Thus, the final PK model is described as follows:

-

CL = 37.8 × EXP (0.207 × (temperature − 36.9)) L h−1

-

V1 = 229 L

-

V2 = 1640 × (total plasma protein/4.5)2.46 L

-

Q = 41 L h−1

Model evaluation and simulation

The final parameter estimates and IIVs along with their bootstrap CIs are provided in Table 2. All parameters had acceptable relative standard error values. The population mean estimates were contained within the 95% CIs of the bootstrap results.

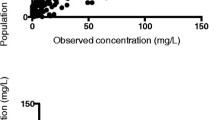

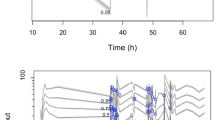

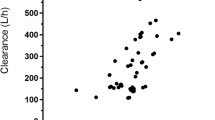

Figure 1 a–d show the goodness-of-fit plots. Both the population predictions and individual predictions were distributed relatively symmetrically around the line of unity when plotted against the observations. In addition, the CWRES versus time and versus population predictions did not show any trends and were approximately uniformly distributed around zero in the final model. The pc-VPCs revealed that the 5th to 95th percentiles of the predicted data overlaid most of the observed data, indicating good precision of the PK model (Fig. 2). The final covariate model was then used for simulations. Figure 3 shows the Monte Carlo simulated sufentanil concentrations during 120-h infusion using two different dosing regimens, stratified by the body temperature and total plasma protein level. The target concentrations were set to 0.3–0.6 μg L−1. Overall, the concentrations of sufentanil are increased in patients with low body temperature and low total plasma protein levels.

Goodness-of-fit plots of the final population pharmacokinetic model. Log of observed sufentanil concentrations versus log of population predicted concentrations (a) and versus log of individual predicted concentrations (b), and conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus population predicted concentrations (c) and versus time (d)

Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks (pc-VPCs) of the final population pharmacokinetic model. Open circles, observed sufentanil concentrations; solid line, median; lower and upper dashed lines, 5th and 95th percentiles of the simulated data, respectively; shaded areas, 95% confidence intervals for simulated predicted median, 5th percentile, and 95th percentile constructed from 1000 simulated datasets of individuals from the original dataset

Simulated mean sufentanil concentrations for 120-h sufentanil infusion in patients. Patients were stratified for body temperature (a, c) or total plasma protein (b, d). a 12.5 μg h−1 infusion in patients with total plasma protein levels of 4.5 g dL−1. b 12.5 μg h−1 infusion in patients with body temperatures of 36.9 °C. c 17.5 μg h−1 infusion in patients with total plasma protein levels of 4.5 g dL−1. d 17.5 μg h−1 infusion in patients with body temperatures of 36.9 °C

Figure 3 a and c reveal the effect of different body temperatures on sufentanil concentrations. With a dose of 17.5 μg h−1, the concentrations of sufentanil from 24 to 120 h were within the target concentrations in patients with a body temperature of 35–38 °C, whereas they were above the target concentrations in patients developing hypothermia (33 °C) and under the target concentrations in patients with high fever (39 °C).

Figure 3b and d show the effect of different total plasma protein levels on sufentanil concentrations. With a dose of 17.5 μg h−1, sufentanil concentrations were within target concentrations in most patients, whereas a dose of 12.5 μg h−1 was low for patients with total plasma protein levels of 4–8 g dL−1.

Discussion

We analysed a population of 20 critically ill ECMO patients who received sufentanil-based analgesia and sedation, and we described a population PK model. A two-compartment model with first-order elimination fitted the time course of the total plasma sufentanil concentrations best. In our final model, increased Vd (V1, 229 L; V2, 1640 L, standardised total plasma protein level of 4.5 g dL−1) and decreased values for clearance (CL, 37.8 L h−1, standardised temperature of 36.9 °C; Q, 41 L h−1) were reported compared with previous PK data from non-critically ill patients (V1, 37.1 L; V2, 92.7 L; CL, 76.2 L h−1; Q, 52.2 L h−1) [20] and critically ill patients not undergoing ECMO (Vd, 1582 L; CL, 56 L h−1) [21]. Sufentanil, as a highly lipophilic (logP = 3.24) and high protein-binding (91–93%) drug [22], could be largely sequestered in the ECMO circuit, which mimics an increase in Vd [15]. Moreover, a systemic inflammatory response, which can be triggered by the patient’s clinical condition or the initiation of ECMO, alters permeability of the blood-brain barrier and impacts the Vd of sufentanil [13]. Decreased CL may have resulted from the reduced hepatic blood flow and impaired hepatic function in critically ill patients [23]. Although nine patients received CVVHDF concomitantly with ECMO, it would have little effect on sufentanil PK. Primary mechanism of sufentanil clearance is the liver. Also, the drug is lipophilic, exhibits highly protein binding, and has a relatively high molecular weight (386.552 g/mol). Thus, it is expected that sufentanil would not be removed by CVVHDF, with limited clearance by VA-ECMO.

Body temperature and total protein level were found to be significant covariates of sufentanil PK, and interestingly, weight-related covariates were not included in the final model. In previous sufentanil PK studies in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, adding weight as a covariate showed neither a significant change in log-likelihood nor an improvement in predictive ability due to the large impact of coronary artery bypass surgery on sufentanil PK [16, 24]. Since ECMO also has a large impact on sufentanil PK, we concluded that body weight is rendered insignificant as a factor in our final model.

The relationship between body temperature and sufentanil systemic clearance was described as follows: CL = 37.8 × EXP (0.207 × (temperature − 36.9)) L h−1. These results are in agreement with the findings of previous studies, in which sufentanil showed decreased clearance in hypothermic patients [25,26,27]. There are several processes that may be responsible for a decrease in sufentanil CL as body temperature drops. Sufentanil, a drug with a high liver-extraction ratio (hepatic extraction ratio of 0.7), is expected to be sensitive to blood flow alterations [11]. When body temperature drops, total hepatic blood flow is assumed to be markedly reduced [28], which then reduces the hepatic elimination of sufentanil. Furthermore, sufentanil metabolism occurs mainly via the cytochrome P450 system (CYP450), which is known to be strongly affected by temperature. Low temperature changes the binding pocket confirmation of CYP3A4, which reduces substrate affinity for CYP3A4 binding sites and slows CYP3A4 metabolic activity [29]. In recent studies, CYP3A4*1G genetic polymorphism was found to be correlated with a lower amount of sufentanil consumption due to impaired activity of CYP3A4 [30, 31]. The frequency of the CYP3A4*1G variant allele showed big difference by ethnicity, which was 0.188–0.279 in Chinese patients [32] and 0.079 in Caucasian patients [33]. In further studies, CYP3A4 polymorphism should be considered when extrapolating our data to other patient groups.

The effect of temperature is especially relevant in ECMO patients who show variability in body temperature for many reasons. The body temperature of ECMO patients could drop because of repeated blood transfusion, infusion of fluid, severe infection, and sepsis. In addition, to minimise brain damage, the body temperatures of ECMO patients after cardiac arrest are not allowed to exceed 36 °C over 24 h. In contrast, some ECMO patients could develop fever, which is associated, for example, with inflammation, elevated sympathetic tone, and catheter-related infections.

We also found that total plasma protein level was correlated positively with V2. Our results are different from those of other studies, in which total protein level was negatively correlated with V2 [34–36]. One teicoplanin PK study demonstrated that a reduction in protein binding due to hypoproteinaemia could promote the distribution of the free form of teicoplanin into extravascular or intracellular spaces, thus increasing the volume of distribution [35]. However, our finding could be explained by the fact that sufentanil binding is affected mainly by the plasma concentration of α1-acid glycoprotein, and not by the total plasma protein level. Low total protein levels might reflect impaired hepatic function, which could produce low apparent volumes of distribution [37]. We want to highlight that our results are observatory and further studies are needed to fully uncover the relationship between total protein level and volume of distribution. Furthermore, our estimates of V2 shrinkage were relatively high (33%), so these estimates should be interpreted with caution.

Targeted sufentanil plasma concentrations in critically ill patients have not yet been determined accurately with PK/pharmacodynamic studies. Pain and sedation management are important consideration in the care of the ECMO patients, and no practice guidelines exist for this population. Recent evidences suggest sedative/analgesic protocols aiming for minimal and lighter sedation to improve clinical outcomes [38, 39]. With limited data in patients with cardiac surgery together [40,41,42,43], we suggested a target concentration between 0.3 and 0.6 μg mL−1 to ensure sedation and better clinical outcomes. Overall, an infusion of 17.5 μg h−1 seems better than 12.5 μg h−1 in most ECMO patients, except hypothermia patients (33 °C). In hypothermic patients, over-sedation, which could induce respiratory depression, needs to be monitored especially when their total plasma protein level is low. With assessment of the analgesia and sedative levels, dose reductions should be considered. On the contrary, optimal levels of analgesia and sedation could not be induced with commonly used doses in hyperthermic patients, which suggests that an increased dose should be considered.

Our study did have several limitations. First, although the hepatic clearance of sufentanil is largely dependent on hepatic plasma flow, we did not observe hepatic blood flow as a potential covariate of CL in our PK model. Second, the concomitant use of sedating and paralysing medications prevented us from exploring the pharmacodynamics of sufentanil in terms of the level of sedation and analgesia. Future prospective studies that control for the presence of concomitant sedating and paralysing agents and that measure the exact degree of sedation and analgesia score are needed to link drug concentrations to the level of sedation and analgesia to determine appropriate concentrations. Nevertheless, the model developed in our study could be used for future sufentanil dosing considerations and the design of clinical studies in patients using ECMO.

Conclusions

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on a population PK model of sufentanil in ECMO patients. The sufentanil volume of distribution was increased, and clearance was decreased in VA-ECMO patients compared with the values from previously reported non-ECMO patients. Body temperature and total plasma protein level correlated positively with CL and V2, respectively. The influence of body temperature and total plasma protein on the PK of sufentanil should be considered. Further research should focus on the pharmacodynamics of sufentanil, such as sedation and analgesia levels and haemodynamic stability in patients during VA-ECMO.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and institutional policy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CL:

-

Systemic clearance

- CRRT:

-

Continuous renal replacement therapy

- CVVHDF:

-

Continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration

- CWRES:

-

Conditional weighted residuals

- CYP450:

-

Cytochrome P450 system

- df:

-

Degrees of freedom

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetate

- IIV:

-

Inter-individual variability

- IPRED:

-

Individual predictions

- NONMEM:

-

Nonlinear mixed effects modelling

- OFV:

-

Objective function value

- pc-VPC:

-

Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks

- PK:

-

Pharmacokinetics

- PRED:

-

Population predictions

- Q:

-

Intercompartmental clearance

- V1:

-

Central volume of distribution

- V2:

-

Peripheral volume of distribution

- VA-ECMO:

-

Venoarterial ECMO

References

Asaumi Y, Yasuda S, Morii I, Kakuchi H, Otsuka Y, Kawamura A, Sasako Y, Nakatani T, Nonogi H, Miyazaki S. Favourable clinical outcome in patients with cardiogenic shock due to fulminant myocarditis supported by percutaneous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(20):2185–92.

Shekar K, Mullany DV, Thomson B, Ziegenfuss M, Platts DG, Fraser JF. Extracorporeal life support devices and strategies for management of acute cardiorespiratory failure in adult patients: a comprehensive review. Critical Care. 2014;18(3):219.

Adkins KL. Sedation strategies for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. ASAIO J. 2017;63(2):113–4.

Wildschut ED, Hanekamp MN, Vet NJ, Houmes RJ, Ahsman MJ, Mathot RA, de Wildt SN, Tibboel D. Feasibility of sedation and analgesia interruption following cannulation in neonates on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(9):1587–91.

Anton-Martin P, Modem V, Taylor D, Potter D, Darnell-Bowens C. A retrospective study of sedation and analgesic requirements of pediatric patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) from a single-center experience. Perfusion. 2017;32(3):183–91.

Zalieckas J, Weldon C. Sedation and analgesia in the ICU. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2015;24(1):37–46.

DeBerry BB, Lynch JE, Chernin JM, Zwischenberger JB, Chung DH. A survey for pain and sedation medications in pediatric patients during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2005;20(3):139–43.

DeGrado JR, Hohlfelder B, Ritchie BM, Anger KE, Reardon DP, Weinhouse GL. Evaluation of sedatives, analgesics, and neuromuscular blocking agents in adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care. 2017;37:1–6.

Bovill JG, Sebel PS, Blackburn CL, Oei-Lim V, Heykants JJ. The pharmacokinetics of sufentanil in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 1984;61(5):502–6.

Meuldermans W, Hurkmans R, Heykants J. Plasma protein binding and distribution of fentanyl, sufentanil, alfentanil and lofentanil in blood. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1982;257(1):4–19.

Scholz J, Steinfath M, Schulz M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of alfentanil, fentanyl and sufentanil. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31(4):275–92.

Shekar K, Roberts JA, Welch S, Buscher H, Rudham S, Burrows F, Ghassabian S, Wallis SC, Levkovich B, Pellegrino V, et al. ASAP ECMO: Antibiotic, Sedative and Analgesic Pharmacokinetics during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: a multi-centre study to optimise drug therapy during ECMO. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012;12:29.

Shekar K, Fraser JF, Smith MT, Roberts JA. Pharmacokinetic changes in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care. 2012;27(6):741.e749–18.

Tukacs M. Pharmacokinetics and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: a literature review. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2018;29(3):246–58.

Ha MA, Sieg AC. Evaluation of altered drug pharmacokinetics in critically ill adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(2):221–35.

Hudson RJ, Thomson IR, Jassal R. Effects of cardiopulmonary bypass on sufentanil pharmacokinetics in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(4):862–71.

Raffaeli G, Allegaert K, Koch B, Cavallaro G, Mosca F, Tibboel D, Wildschut ED. In vitro adsorption of analgosedative drugs in new extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuits. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(5):e251–8.

Mould DR, Upton RN. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development-part 2: introduction to pharmacokinetic modeling methods. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2:e38.

Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN. PsN-Toolkit--a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2005;79(3):241–57.

Slepchenko G, Simon N, Goubaux B, Levron JC, Le Moing JP, Raucoules-Aime M. Performance of target-controlled sufentanil infusion in obese patients. Anesthesiology. 2003;98(1):65–73.

Ethuin F, Boudaoud S, Leblanc I, Troje C, Marie O, Levron J-C, Le Moing J-P, Assoune P, Eurin B, Jacob L. Pharmacokinetics of long-term sufentanil infusion for sedation in ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(11):1916–20.

Medzihradsky F, Emmerson PJ, Mousigian CA. Lipophilicity of opioids determined by a novel micromethod; 1992.

Campbell GA, Morgan DJ, Kumar K, Crankshaw DP. Extended blood collection period required to define distribution and elimination kinetics of propofol. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26(2):187–90.

Bartkowska-Sniatkowska A, Bienert A, Wiczling P, Rosada-Kurasinska J, Zielinska M, Warzybok J, Borsuk A, Tibboel D, Kaliszan R, Grzeskowiak E. Pharmacokinetics of sufentanil during long-term infusion in critically ill pediatric patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56(1):109–15.

Liu MZ, Silvern DA, Gupte PM, Inchiosa MA Jr, Sanchala V. Development of a real-time algorithm for predicting sufentanil plasma levels during cardiopulmonary-bypass surgery using a systems approach. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1992;39(6):658–61.

Okutani R, Philbin DM, Rosow CE, Koski G, Schneider RC. Effect of hypothermic hemodilutional cardiopulmonary bypass on plasma sufentanil and catecholamine concentrations in humans. Anesth Analg. 1988;67(7):667–70.

Flezzani P, Alvis MJ, Jacobs JR, Schilling MM, Bai S, Reves JG. Sufentanil disposition during cardiopulmonary bypass. Can J Anaesth. 1987;34(6):566–9.

Fritz HG, Holzmayr M, Walter B, Moeritz KU, Lupp A, Bauer R. The effect of mild hypothermia on plasma fentanyl concentration and biotransformation in juvenile pigs. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(4):996–1002.

Tortorici MA, Kochanek PM, Poloyac SM. Effects of hypothermia on drug disposition, metabolism, and response: a focus of hypothermia-mediated alterations on the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9):2196–204.

Lv J, Liu F, Feng N, Sun X, Tang J, Xie L, Wang Y. CYP3A4 gene polymorphism is correlated with individual consumption of sufentanil. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62(10):1367–73.

Zhang H, Chen M, Wang X, Yu S. Patients with CYP3A4*1G genetic polymorphism consumed significantly lower amount of sufentanil in general anesthesia during lung resection. Medicine. 2017;96(4):e6013.

Yuan JJ, Hou JK, Zhang W, Chang YZ, Li ZS, Wang ZY, Du YY, Ma XJ, Zhang LR, Kan QC, et al. CYP3A4 * genetic polymorphism influences metabolism of fentanyl in human liver microsomes in Chinese patients. Pharmacology. 2015;96(1–2):55–60.

Danielak D, Karaźniewicz-Łada M, Wiśniewska K, Bergus P, Burchardt P, Komosa A, Główka F. Impact of CYP3A4*1G allele on clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of clopidogrel. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2017;42(1):99–107.

Ouellet D, Periclou AP, Johnson RD, Woodworth JR, Lalonde RL. Population pharmacokinetics of pemetrexed disodium (ALIMTA) in patients with cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;46(3):227–34.

Ogawa R, Kobayashi S, Sasaki Y, Makimura M, Echizen H. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses of teicoplanin in Japanese patients with systemic MRSA infection. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51(5):357–66.

Moffett BS, Morris J, Galati M, Munoz F, Arikan AA. Population pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(10):973–80.

Guan XF, Li DY, Yin WJ, Ding JJ, Zhou LY, Wang JL, Ma RR, Zuo XC. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of diltiazem in Chinese renal transplant recipients. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2018;43(1):55–62.

Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, Watson PL, Weinhouse GL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):1532–48.

deBacker J, Tamberg E, Munshi L, Burry L, Fan E, Mehta S. Sedation practice in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-treated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective study. ASAIO J. 2018;64(4):544–51.

Jeleazcov C, Saari TI, Ihmsen H, Schuttler J, Fechner J. Changes in total and unbound concentrations of sufentanil during target controlled infusion for cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(5):698–706.

Fechner J, Ihmsen H, Schuttler J, Jeleazcov C. The impact of intra-operative sufentanil dosing on post-operative pain, hyperalgesia and morphine consumption after cardiac surgery. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(4):562–70.

Bourgoin A, Albanese J, Leone M, Sampol-Manos E, Viviand X, Martin C. Effects of sufentanil or ketamine administered in target-controlled infusion on the cerebral hemodynamics of severely brain-injured patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(5):1109–13.

Zhao Y, Zhang LP, Wu XM, Jiang JY, Duan JL, Hu YF, Li M, Liu W, Sheng XY, Ni C, et al. Clinical evaluation of target controlled infusion system for sufentanil administration. Chin Med J. 2009;122(20):2503–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the staff of the cardiac care unit in Severance Cardiovascular Hospital for their routine support and patient care, which was crucial to the successful completion of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning) (No. 2017R1C1B5016737). This research was partially supported by the Graduate School of YONSEI University Research Scholarship Grants in 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH, JW, and MJC designed the study, performed the population PK analysis, interpreted the results of the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. JW and MJC supervised the design, conducted the study, and revised the manuscript. SY, KLM, DK, and BHJ collected the blood sample and patient data. SY and KLM assisted technical PK modelling. CP conducted the drug concentration assay and validation. MSP interpreted the study results and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No.: 4-2014-0919) of Severance Hospital and was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02581280). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or the legal surrogates of unconscious patients.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ legal representatives for publication of their individual details in this manuscript. The consent form is held by the authors’ institution and is available for review by the Editor.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hahn, J., Yang, S., Min, K.L. et al. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous sufentanil in critically ill patients supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy. Crit Care 23, 248 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2508-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2508-4